Determinants of HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Insights from the Ghana Men’s Study II

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

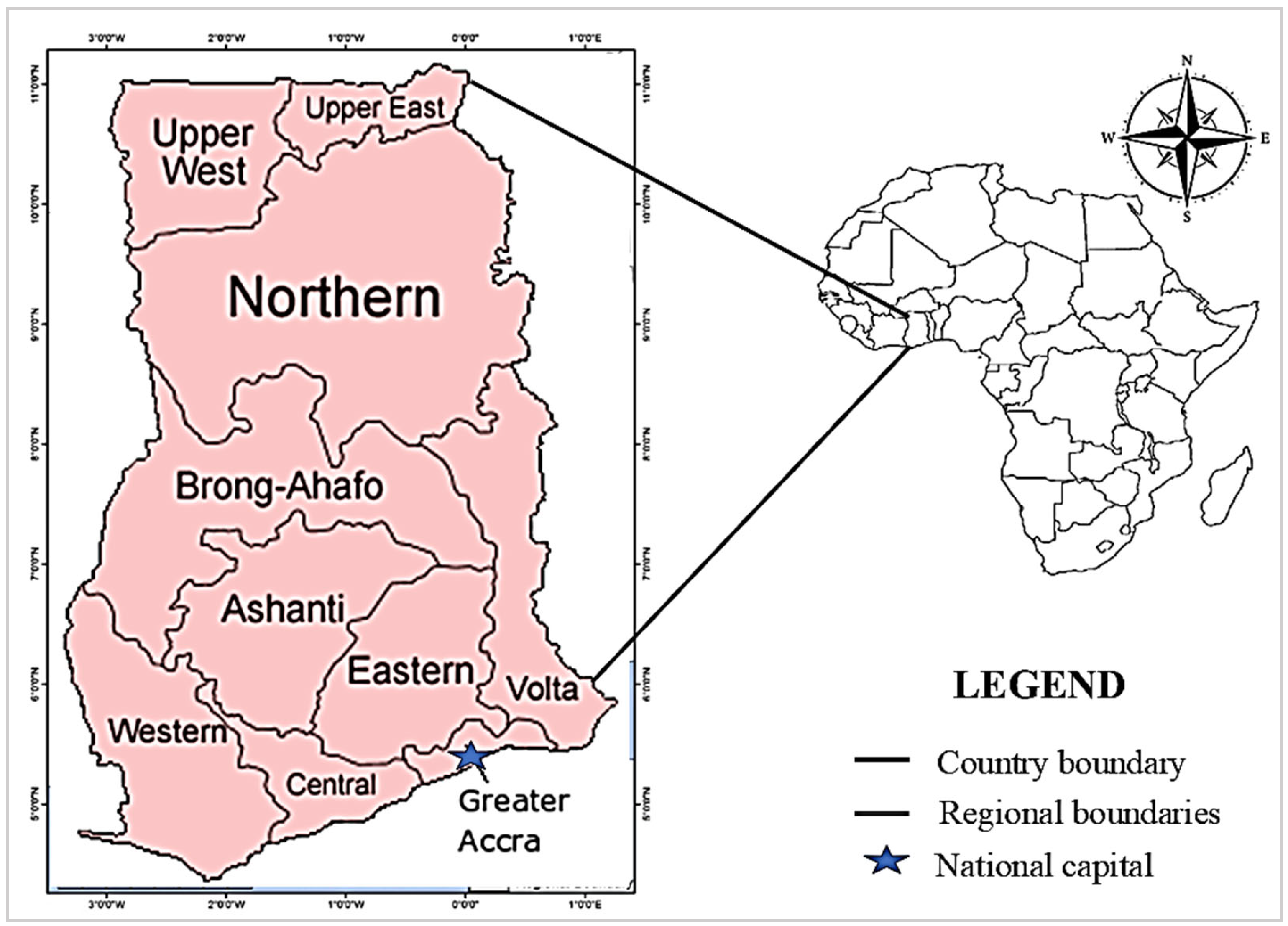

2.1. Study Design and Study Setting

2.2. Sampling and Data Collection

2.3. Reliability and Validity

2.4. Method of Data Analysis

2.4.1. Descriptive Statistics

2.4.2. Bivariate and Multivariable Logistic Regression

3. Results

3.1. Socio-Demographic Characteristics of the Study Participants

3.2. Behavioural Practices of the MSM Population in Ghana

3.3. Sexual Practices of the MSM Study Participants

3.4. Structural and Clinical Characteristics of the MSM Study Participants

3.5. Associated Factors of HIV Testing Among MSM in Ghana

4. Discussion

4.1. Socio-Demographic Factors Associated with HIV Testing Among MSM

4.2. Bahavioural Factors Affecting HIV Testing Among MSM

4.3. Relationships Between Factors Influencing HIV Testing Among MSM in Ghana

4.4. Strengths and Limitations of the Study

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SAMRC/UJ | South Africa Medical Research Council/University of Johannesburg |

| PACER | Pan African Centre for Epidemics |

| KNUST | Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology |

| AIDS | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| MSM | Men who have sex with men |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| WHO | World Health Organization |

| SDG | Sustainable Development Goal |

| GAC | Ghana AIDS Commission |

| TB | Tuberculosis |

| STI | Sexually transmitted infection |

| PEPFAR | President’s Emergency Plan for AIDS Relief |

| GMS II | Ghana Men’s Study II |

| IBBSS | Integrated Bio-Behavioural Surveillance Survey |

| RDS | Respondent-driven sampling |

| ORs | Odds ratios |

| CIs | Confidence intervals |

| AOR | Adjusted Odds Ratio |

| NGO | Non-governmental organisation |

| LGBTQ+ | Lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer |

| REC | Research Ethics Committee |

References

- World Health Organisation. HIV and AIDS. Key Facts. 2023. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/hiv-aids (accessed on 25 September 2023).

- Hessou, P.S.; Glele-Ahanhanzo, Y.; Adekpedjou, R.; Ahouada, C.; Johnson, R.C.; Boko, M.; Zomahoun, H.T.; Alary, M. Comparison of the prevalence rates of HIV infection between men who have sex with men (MSM) and men in the general population in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 1634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kloek, M.; Bulstra, C.A.; van Noord, L.; Al-Hassany, L.; Cowan, F.M.; Hontelez, J.A. HIV prevalence among men who have sex with men, transgender women, and cisgender male sex workers in sub-Saharan Africa: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2022, 25, e26022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carneiro, A.M.F.; Rodrigues, Y.C.; de Sousa Gomes, J.; Costa Lima, L.N.G.; Batista Lima, K.V.; Dolabela, M.F. The Negative Impact of Stigma Perceived by Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM): An Integrative Review. Int. J. Curr. Microbiol. App. Sci. 2022, 11, 366–378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kushwaha, S.; Lalani, Y.; Maina, G.; Ogunbajo, A.; Wilton, L.; Agyarko-Poku, T.; Adu-Sarkodie, Y.; Boakye, F.; Zhang, N.; Nelson, L.E. “But the moment they find out that you are MSM…”: A qualitative investigation of HIV prevention experiences among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Ghana’s health care system. BMC Public Health 2017, 17, 770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueroa, J.P.; Cooper, C.J.; Edwards, J.K.; Byfield, L.; Eastman, S.; Hobbs, M.M.; Weir, S.S. Understanding the high prevalence of HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among socio-economically vulnerable men who have sex with men in Jamaica. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0117686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otambo, P.C.; Makokha, A.; Karama, M.; Mwangi, M. Accessibility to, acceptability of, and adherence to HIV/AIDS prevention services by men who have sex with men: Challenges encountered at facility level. Adv. Public Health 2016, 2016, 5157984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldenburg, C.E.; Perez-Brumer, A.G.; Reisner, S.L.; Mimiaga, M.J. Transactional sex and the HIV epidemic among men who have sex with men (MSM): Results from a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Behav. 2015, 19, 2177–2183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Z.J.; He, N.; Nehl, E.J.; Zheng, T.; Smith, B.D.; Zhang, J.; McNabb, S.; Wong, F.Y. Social network and other correlates of HIV testing: Findings from male sex workers and other MSM in Shanghai, China. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16, 858–871. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Lu, H.; Ma, X.; Sun, Y.; He, X.; Li, C.; Raymond, H.F.; McFarland, W.; Pan, S.W.; Shao, Y.; et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigmatizing and discriminatory attitudes and recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in Beijing. AIDS Behav. 2012, 16, 499–507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philbin, M.M.; Hirsch, J.S.; Wilson, P.A.; Ly, A.T.; Giang, L.M.; Parker, R.G. Structural barriers to HIV prevention among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Vietnam: Diversity, stigma, and healthcare access. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0195000. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, C.E.; Baral, S.D.; Fielding-Miller, R.; Adams, D.; Dludlu, P.; Sithole, B.; Fonner, V.A.; Mnisi, Z.; Kerrigan, D. “They are human beings, they are Swazi”: Intersecting stigmas and the positive health, dignity and prevention needs of HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Swaziland. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smit, P.J.; Brady, M.; Carter, M.; Fernandes, R.; Lamore, L.; Meulbroek, M.; Ohayon, M.; Platteau, T.; Rehberg, P.; Rockstroh, J.K.; et al. HIV-related stigma within communities of gay men: A literature review. AIDS Care 2012, 24, 405–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rispel, L.C.; Metcalf, C.A.; Cloete, A.; Moorman, J.; Reddy, V. You become afraid to tell them that you are gay: Health service utilization by men who have sex with men in South African cities. J. Publ. Health Policy 2011, 32, 137–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zahn, R.; Grosso, A.; Scheibe, A.; Bekker, L.G.; Ketende, S.; Dausab, F.; Iipinge, S.; Beyrer, C.; Trapance, G.; Baral, S. Human rights violations among men who have sex with men in Southern Africa: Comparisons between legal contexts. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0147156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pyun, T.; Santos, G.M.; Arreola, S.; Do, T.; Hebert, P.; Beck, J.; Makofane, K.; Wilson, P.A.; Ayala, G. Internalized homophobia and reduced HIV testing among men who have sex with men in China. Asia Pac. J. Public Health 2014, 26, 118–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babel, R.A.; Wang, P.; Alessi, E.J.; Raymond, H.F.; Wei, C. Stigma, HIV risk, and access to HIV prevention and treatment services among men who have sex with men (MSM) in the United States: A scoping review. AIDS Behav. 2021, 25, 3574–3604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahlman, S.; Sanchez, T.H.; Sullivan, P.S.; Ketende, S.; Lyons, C.; Charurat, M.E.; Drame, F.M.; Diouf, D.; Ezouatchi, R.; Kouanda, S.; et al. The prevalence of sexual behavior stigma affecting gay men and other men who have sex with men across sub-Saharan Africa and in the United States. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2016, 2, e5824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, G.M.; Nelson, L.E.; Ogunbajo, A.; Boakye, F.; Appiah, P.; Odhiambo, A.; Sa, T.; Zhang, N.; Ngozi, I.; Scott, A.; et al. Implementation and evaluation of a culturally grounded group-based HIV prevention programme for men who have sex with men in Ghana. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 1028–1045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghana Aids Commission. Ghana Men’s Study. Mapping and Population Size Estimation (MPSE) and Integrated Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey (IBBSS) Amongst Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in Ghana (Round II). Accra, Ghana. 2017. Available online: http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11910/15238 (accessed on 25 May 2025).

- Abdulai, R.; Phalane, E.; Atuahene, K.; Kwao, I.D.; Afriyie, R.; Shiferaw, Y.A.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. Consistency of Condom Use with Lubricants and Associated Factors Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Evidence from Integrated Bio-Behavioral Surveillance Survey. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chow, E.P.; Wilson, D.P.; Zhang, L. The rate of HIV testing is increasing among men who have sex with men in China. HIV Med. 2012, 13, 255–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wimonsate, W.; Naorat, S.; Varangrat, A.; Phanuphak, P.; Kanggarnrua, K.; McNicholl, J.; Akarasewi, P.; van Griensven, F. Factors associated with HIV testing history and returning for HIV test results among men who have sex with men in Thailand. AIDS Behav. 2011, 15, 693–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baral, S.D.; Ketende, S.; Mnisi, Z.; Mabuza, X.; Grosso, A.; Sithole, B.; Maziya, S.; Kerrigan, D.L.; Green, J.L.; Kennedy, C.E.; et al. A cross-sectional assessment of the burden of HIV and associated individual-and structural-level characteristics among men who have sex with men in Swaziland. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2013, 16, 18768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knussen, C.; Flowers, P.; McDaid, L.M. Factors associated with recency of HIV testing amongst men residing in Scotland who have sex with men. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 297–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hakim, A.J.; Aho, J.; Semde, G.; Diarrassouba, M.; Ehoussou, K.; Vuylsteke, B.; Murrill, C.S.; Thiam, M.; Wingate, T.; SHARM Study Group. The epidemiology of HIV and prevention needs of men who have sex with men in Abidjan, Cote d’Ivoire. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0125218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berry, M.; Wirtz, A.L.; Janayeva, A.; Ragoza, V.; Terlikbayeva, A.; Amirov, B.; Baral, S.; Beyrer, C. Risk factors for HIV and unprotected anal intercourse among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Almaty, Kazakhstan. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e43071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scott, H.M.; Pollack, L.; Rebchook, G.M.; Huebner, D.M.; Peterson, J.; Kegeles, S.M. Peer social support is associated with recent HIV testing among young black men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2014, 18, 913–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayala, G.; Santos, G.M. Will the global HIV response fail gay and bisexual men and other men who have sex with men? J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016, 19, 21098. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngcobo, S.J.; Zhandire, T. The Role of Traditional and Religious Beliefs in HIV Testing and Prevention in Africa: A Scoping Review Protocol. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2025, 22, 743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Xiao, Y.; Lu, R.; Wu, G.; Ding, X.; Qian, H.Z.; McFarland, W.; Ruan, Y.; Vermund, S.H.; Shao, Y. Predictors of HIV testing among men who have sex with men in a large Chinese city. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013, 40, 235–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Chen, Y.; Yao, T.; Zhang, T.; Song, D.; Liu, Y.; Yu, M.; Xu, J.; Li, Z.; Yang, J.; et al. Factors related to HIV testing frequency in MSM based on the 2011–2018 survey in Tianjin, China: A hint for risk reduction strategy. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nel, J.A.; Yi, H.; Sandfort, T.G.; Rich, E. HIV-untested men who have sex with men in South Africa: The perception of not being at risk and fear of being tested. AIDS Behav. 2013, 17, 51–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; He, W.; Pan, H.; Zhong, X. A structural equation modeling approach to investigate HIV testing willingness for men who have sex with men in China. AIDS Res. Ther. 2023, 20, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Staneková, D.; Kramárová, P.; Wimmerová, S.; Hábeková, M.; Takáčová, M.; Mojzesová, M. HIV and risk behaviour among men who have sex with men in Slovakia (2008–2009). Cent. Eur. J. Public Health 2014, 22, 239–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Inghels, M.; Kouassi, A.K.; Niangoran, S.; Bekelynck, A.; Carilon, S.; Sika, L.; Koné, M.; Danel, C.; du Loû, A.D.; Larmarange, J. Preferences and access to community-based HIV testing sites among men who have sex with men (MSM) in Côte d’Ivoire. BMJ Open 2022, 12, e052536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schweitzer, A.M.; Dišković, A.; Krongauz, V.; Newman, J.; Tomažič, J.; Yancheva, N. Addressing HIV stigma in healthcare, community, and legislative settings in Central and Eastern Europe. AIDS Res. Ther. 2023, 20, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- da Cruz, M.M.; Cota, V.L.; Lentini, N.; Bingham, T.; Parent, G.; Kanso, S.; Rosso, L.R.; Almeida, B.; Cardoso Torres, R.M.; Nakamura, C.Y.; et al. Comprehensive approach to HIV/AIDS testing and linkage to treatment among men who have sex with men in Curitiba, Brazil. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0249877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashisht, S.; Rai, S.; Kant, S.; Haldar, P.; Goswami, K.; Misra, P.; Reddy, D.; Panda, S. Utilization of HIV testing services among men who have sex with men in New Delhi, India: A qualitative study on barriers and facilitators. Research Square 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Ma, J.; Jiang, S.; Liu, Y.; Sun, Z. Factors associated with HIV testing among MSM in Guilin, China: Results from a cross-sectional study. Int. J. Public Health 2022, 67, 1604612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabin, L.L.; Beard, J.; Agyarko-Poku, T.; DeSilva, M.; Ashigbie, P.; Segal, T.; Esang, M.; Asafo, M.K.; Wondergem, P.; Green, K.; et al. “Too Much Sex and Alcohol”: Beliefs, Attitudes, and Behaviors of Male Adolescents and Young Men Who have Sex with Men in Ghana. Open AIDS J. 2018, 12, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Endalamaw, A.; Gilks, C.F.; Assefa, Y. Socioeconomic inequality in adults undertaking HIV testing over time in Ethiopia based on data from demographic and health surveys. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0296869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakari, G.M.; Turner, D.; Nelson, L.E.; Odhiambo, A.J.; Boakye, F.; Manu, A.; Torpey, K.; Wilton, L. An application of the ADAPT-ITT model to an evidence-based behavioral HIV prevention intervention for men who have sex with men in Ghana. Int. Health Trends Perspect. 2021, 1, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, K.; Vaqar, S.; Gulick, P.G. HIV Prevention; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Guure, C.; Puplampu, A.E.; Dery, S.; Abu-Ba’are, G.R.; Afagbedzi, S.K.; Ayisi Addo, S.; Torpey, K. Syphilis among HIV-positive men who have sex with men in Ghana: The 2023 biobehavioral survey. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0310909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stangl, A.L.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Logie, C.H.; Van Brakel, W.C.; Simbayi, L.; Barré, I.; Dovidio, J.F. The Health Stigma and Discrimination Framework: A global, crosscutting framework to inform research, intervention development, and policy on health-related stigmas. BMC Med. 2019, 17, 1–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Variable Name | Variables | Variable Descriptions | Variable Recode |

|---|---|---|---|

| Dependent Variable (HIV Testing) | |||

| HIV testing | Whether the respondent has undergone HIV testing | (1) Yes (2) No (3) No response | (1) Yes (2) No |

| HIV counselling | Whether the respondent received HIV counselling | (1) Yes (2) No (3) No response | (1) Yes (2) No |

| HIV diagnosis | Whether the respondent was diagnosed with HIV | (1) Yes (2) No (3) No response | (1) Yes (2) No |

| Linkage to HIV medical care | Whether the respondent, if HIV positive, was linked to medical care | (1) Yes (2) No (3) No response | (1) Yes (2) No |

| HIV testing frequency | Number of HIV tests done | Integer | Integer |

| HIV testing facility types | Platform used for HIV testing | (1) HIV self-testing (2) Mobile testing (3) Community-based testing (4) Facility-based testing (5) Point-of-care testing | (1) HIV self-testing (2) Mobile testing (3) Community-based testing (4) Facility-based testing (5) Point-of-care testing |

| Reasons for HIV testing | Reasons for undergoing HIV testing | (1) Know my status (2) Exposed to risk (3) Healthcare worker Recommendations (4) Regular medical check-up (5) Other (please specify) | (1) Know my status (2) Exposed to risk (3) Healthcare worker Recommendations (4) Regular medical check-up (5) Other (please specify) |

| Independent Variables | |||

| Socio-demographic | |||

| Age | Respondent’s age | Integer | (1) ≥18 (2) 20–24 (3) 25–29 (4) 30–34 (5) 35–39 (6) 40–44 (7) 45–49 (8) 50–54 (9) 55–59 (10) ≥60 |

| Education | The educational level of the respondents | (1) No formal education (2) Basic education (3) Secondary education (4) Tertiary education | (1) No formal education (2) Basic education (3) Secondary education (4) Tertiary education |

| Occupation | Respondents employment status | (1) Unemployed (2) Self-employed (3) Government-employed (4) Private-sector employed | (1) Unemployed (2) Self-employed (3) Government-employed (4) Private-sector employed |

| Steady partner | Whether the respondent has a steady partner | (1) Yes (2) No (3) No response | (1) Yes (2) No |

| Behavioural factors | Behaviours that affect HIV testing | (1) HIV risk perception (2) HIV knowledge and attitude (3) HIV testing history (4) Knowledge of HIV status (5) Sexual practices and partnerships (6) Alcohol use (7) Physical abuse | “(1) HIV risk perception” “(2) HIV knowledge and attitude” “(3) HIV testing history” “(4) Knowledge of HIV status” “(5) Sexual practices and partnerships” “(6) Alcohol use” “(7) Physical abuse” |

| Structural factors | Structural factors that influence HIV testing | (1) Stigma (2) Discrimination (3) Healthcare accessibility (4) Economic factors (5) Policy Legislation (6) Cultural and Societal norms (7) Geographical factors | (1) Stigma (2) Discrimination (3) Healthcare accessibility (4) Economic factors (5) Policy Legislation (6) Cultural and Societal norms (7) Geographical factors |

| Characteristic | HIV Testing Status | Overall | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM Who Tested for HIV | MSM Who Did Not Test for HIV | n = 4095 1 | ||

| n = 2116 1 | n = 1979 1 | |||

| Age in years | <0.001 | |||

| 18–24 | 36 (1.7%) | 9 (0.5%) | 45 (1.1%) | |

| 25–34 | 1602 (75.7%) | 1735 (87.7%) | 3337 (81.5%) | |

| 35+ | 478 (22.6%) | 235 (11.8%) | 713 (17.4%) | |

| Educational level | <0.001 | |||

| Less than primary | 87 (4.1%) | 95 (4.8%) | 182 (4.4%) | |

| Primary school | 51 (2.4%) | 92 (4.6%) | 143 (3.5%) | |

| Junior High school | 503 (23.8%) | 615 (31.1%) | 1118 (27.3%) | |

| Secondary school | 1150 (54.3%) | 1015 (51.3%) | 2165 (52.9%) | |

| Tertiary or higher | 325 (15.4%) | 162 (8.2%) | 487 (11.9%) | |

| Income status | <0.001 | |||

| No income | 702 (33.2%) | 829 (41.9%) | 1531 (37.4%) | |

| Low income | 1019 (48.2%) | 917 (46.3%) | 1936 (47.3%) | |

| Middle income | 181 (8.5%) | 123 (6.2%) | 304 (7.4%) | |

| High income | 214 (10.1%) | 110 (5.6%) | 324 (7.9%) | |

| Marital status | 0.002 | |||

| Single/Never Married | 1971 (93.1%) | 1881 (95%) | 3852 (94.1%) | |

| Married/living with a woman | 102 (4.8%) | 82 (4.1%) | 184 (4.5%) | |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 43 (2.0%) | 16 (0.8%) | 59 (1.4%) | |

| Living status of participant | <0.001 | |||

| Alone | 992 (46.9%) | 774 (39.1%) | 1766 (43.1%) | |

| Female sexual partner | 112 (5.3%) | 84 (4.3%) | 196 (4.8%) | |

| Male Sexual partner | 57 (2.7%) | 41 (2.1%) | 98 (2.4%) | |

| With other relatives | 221 (10.4%) | 248 (12.5%) | 469 (11.5%) | |

| With parents and/or siblings | 732 (34.6%) | 824 (41.6%) | 1556 (38.0%) | |

| Other | 2 (0.1%) | 8 (0.4%) | 10 (0.2%) | |

| Employment status | <0.001 | |||

| Unemployed | 799 (37.8%) | 936 (47.3%) | 1735 (42.4%) | |

| Informal | 467 (22.1%) | 443 (22.4%) | 910 (22.2%) | |

| Formal | 522 (24.7%) | 331 (16.7%) | 853 (20.8%) | |

| Sex worker | 18 (0.9%) | 14 (0.7%) | 32 (0.8%) | |

| Other | 310 (14.5%) | 255 (11.4%) | 565 (13.8%) | |

| Religious affiliation | <0.001 | |||

| Christian | 1538 (72.7%) | 1307 (66.0%) | 2845 (69.5%) | |

| Muslim | 214 (10.1%) | 314 (15.9%) | 528 (12.9%) | |

| Traditional | 48 (2.3%) | 49 (2.5%) | 97 (2.4%) | |

| Other | 248 (11.7%) | 226 (11.4%) | 474 (11.5%) | |

| No religion | 68 (3.2%) | 83 (4.2%) | 151 (3.7%) | |

| Characteristic | HIV Testing Status | Overall | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM Who Tested for HIV | MSM Who Did Not Test for HIV | n = 4095 1 | ||

| n = 2104 1 | n = 1991 1 | |||

| HIV knowledge and attitude | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1464 (69.0%) | 1192 (60.0%) | 2656 (65.0%) | |

| No | 646 (31.0%) | 793 (40.0%) | 1439 (35.0%) | |

| Sexual orientation | <0.001 * | |||

| Gay | 920 (43.5%) | 850 (42.9%) | 1770 (43.2%) | |

| Bisexual | 980 (46.3%) | 883 (44.6%) | 1863 (45.5%) | |

| Straight | 190 (9.0%) | 239 (12.1%) | 429 (10.5%) | |

| Transgender | 26 (1.2%) | 7 (0.4%) | 33 (0.8%) | |

| Alcohol use | <0.001 | |||

| Abstainers | 1492 (70.9%) | 1565 (78.6%) | 3057 (74.7%) | |

| Low risk-Light drinker | 484 (23.0%) | 322 (16.1%) | 806 (19.7%) | |

| Moderate drinker | 85 (4.1%) | 67 (3.4%) | 152 (3.7%) | |

| High risk/Harmful Drinker | 43 (2.0%) | 37 (1.9%) | 80 (1.9%) | |

| Characteristic | HIV Testing Status | Overall | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM Who Tested for HIV | MSM Who Did Not Test for HIV | n = 4095 1 | ||

| n = 2123 1 | n = 1972 1 | |||

| In the last 12 months, how many times have you been spat on, slapped or force you to have sex with | <0.001 | |||

| No times, did not happen | 1911 (90.0%) | 1862 (94.4%) | 3773 (92.1%) | |

| One or more times | 171 (8.1%) | 90 (4.6%) | 261 (6.4%) | |

| Decline to answer | 41 (1.9%) | 20 (1.0%) | 61 (1.5%) | |

| During your first sexual encounter with another man, were you forced or coerced to have sex with this male partner? | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 408 (19.2%) | 370 (18.7%) | 778 (19.1%) | |

| No | 1668 (78.6%) | 1577 (80.0%) | 3245 (79.2%) | |

| Don’t know | 32 (1.5%) | 6 (0.3%) | 38 (0.9%) | |

| Decline to answer | 15 (0.7%) | 19 (1.0%) | 34 (0.8%) | |

| The last time you had sex with your main/regular male partner, did you use a condom? | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1328 (62.6%) | 995 (50.5%) | 2323 (56.7%) | |

| No | 480 (22.6%) | 678 (34.3%) | 1158 (28.3%) | |

| I don’t have a male/regular partner | 283 (13.3%) | 278 (14.1%) | 561 (13.7%) | |

| Don’t know | 21 (1.0%) | 9 (0.5%) | 30 (0.7%) | |

| Decline to answer | 11 (0.5%) | 12 (0.6%) | 23 (0.6%) | |

| The last time you had sex with a man who you received money from in exchange for sex, did you use a condom? | <0.001 * | |||

| Yes | 642 (30.2%) | 478 (24.2%) | 1120 (27.4%) | |

| No | 221 (10.4%) | 345 (17.5%) | 566 (13.8%) | |

| I don’t have a man I received money from | 1245 (58.7%) | 1137 (57.7%) | 2382 (58.1%) | |

| Don’t know | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Decline to answer | 15 (0.7%) | 12 (0.6%) | 27 (0.7%) | |

| The last time you had sex with a man you gave money to in exchange for sex, did you use a condom? | <0.001 * | |||

| Yes | 448 (21.1%) | 275 (13.9%) | 723 (17.7%) | |

| No | 190 (8.9%) | 232 (11.8%) | 422 (10.3%) | |

| I don’t have a man I gave money | 1460 (68.8%) | 1453 (73.7%) | 2913 (71.1%) | |

| Don’t know | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | 0 (0.0%) | |

| Decline to answer | 25 (1.2%) | 12 (0.6%) | 37 (0.9%) | |

| Characteristic | HIV Testing Status | Overall | p-Value 2 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| MSM Who Tested for HIV | MSM Who Did Not Test for HIV | n = 4095 1 | ||

| n = 2129 1 | n = 1966 1 | |||

| Refused health service because of being MSM | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2057 (96.6%) | 1934 (98.4%) | 3991 (97.5%) | |

| Discriminated | 72 (3.4%) | 32 (1.6%) | 104 (2.5%) | |

| Refused employment service because of being MSM | 0.009 | |||

| None | 2044 (96.0%) | 1916 (97.5%) | 3960 (96.7%) | |

| Discriminated | 85 (4.0%) | 50 (2.5%) | 135 (3.3%) | |

| Refused education service because of being MSM | 0.001 | |||

| None | 2038 (96%) | 1918 (98%) | 3956 (97%) | |

| Discriminated | 91 (4.3%) | 48 (2.4%) | 139 (3.4%) | |

| Refused religious/church service because of being MSM | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2059 (97%) | 1941 (99%) | 4000 (98%) | |

| Discriminated | 70 (3.3%) | 25 (1.3%) | 95 (2.3%) | |

| Refused restaurant/bar service because of being MSM | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2049 (96%) | 1937 (99%) | 3986 (97%) | |

| Discriminated | 80 (3.8%) | 29 (1.5%) | 109 (2.7%) | |

| Refused housing service because of being MSM | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2036 (96%) | 1932 (98%) | 3968 (97%) | |

| Discriminated | 93 (4.4%) | 34 (1.7%) | 127 (3.1%) | |

| Refused Police service because of being MSM | <0.001 | |||

| None | 2063 (97%) | 1940 (99%) | 4003 (98%) | |

| Discriminated | 66 (3.1%) | 26 (1.3%) | 92 (2.2%) | |

| Received HIV testing and counselling at health facility in the last 12 months | <0.001 | |||

| Yes | 1682 (80.0%) | 31 (1.6%) | 1713 (41.8%) | |

| No | 411 (19.5%) | 137 (6.9%) | 548 (13.4%) | |

| Don’t know | 8 (0.4%) | 498 (25.0%) | 506 (12.4%) | |

| Decline to answer | 3 (0.1%) | 1325 (66.5%) | 1328 (32.4%) | |

| Variables | Bivariate Analysis | Multivariable Analysis | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % (n) | Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age category, yes | |||||

| 18–24 | 64.39 (1779) | REF | REF | ||

| 25–34 | 31.99(884) | 1.93 (1.63–2.27) | <0.001 | 1.43 (1.18–1.74) | <0.001 |

| 35+ | 3.62 (100) | 2.08 (1.36–3.18) | 0.001 | 1.36 (0.82–2.27) | 0.238 |

| Educational level | |||||

| Less than primary | 2.71 (75) | REF | REF | ||

| Primary school | 3.11 (86) | 0.88 (0.47–1.66) | 0.702 | 0.72 (0.37–1.41) | 0.339 |

| Junior High school | 26.82 (741) | 1.27 (0.78–2.06) | 0.330 | 1.32 (0.79–2.19) | 0.293 |

| Senior High school | 55.23 (1526) | 1.77 (1.10–2.83) | 0.018 | 1.69 (1.02–2.80) | 0.040 |

| Tertiary or higher | 12.12 (335) | 3.24 (1.94–5.43) | <0.001 | 2.03 (1.17–3.55) | 0.012 |

| Marital status | |||||

| Married/living with a woman | 4.63 (128) | REF | REF | ||

| Single/Never Married | 94.03 (2598) | 0.66 (0.46–0.95) | 0.027 | 0.85 (0.56–1.29) | 0.454 |

| Widowed/Divorced/Separated | 1.34 (37) | 2.10 (0.89–4.98) | 0.091 | 1.82 (0.72–4.58) | 0.204 |

| Employment | |||||

| Unemployed | 40.72 (1125) | REF | REF | ||

| Employed | 44.55 (1231) | 1.58 (1.34–1.86) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.85–1.48) | 0.415 |

| Sex worker | 14.73 (407) | 1.31 (1.05–1.65) | 0.019 | 1.07 (0.79–1.44) | 0.679 |

| Religion | |||||

| Christianity | 71.88 (1986) | REF | REF | ||

| Muslim | 11.98 (331) | 0.59 (0.47–0.75) | <0.001 | 0.69 (0.54–0.90) | 0.005 |

| Traditional | 1.81 (50) | 0.83 (0.48–1.46) | 0.527 | 0.88 (0.48–1.64) | 0.697 |

| Other | 11.00 (304) | 0.84 (0.66–1.08) | 0.171 | 0.89 (0.68–1.15) | 0.360 |

| No religion | 3.33 (92) | 0.65 (0.43–0.98) | 0.042 | 0.80 (0.51–1.25) | 0.323 |

| Income status (GHS) | |||||

| No Income | 35.36 (977) | REF | REF | ||

| Low Income (1–599 cedis/month) | 48.82 (1349) | 1.31 (1.11–1.54) | 0.002 | 1.14 (0.88–1.49) | 0.319 |

| Middle Income (600–999 cedis/month) | 7.46 (206) | 1.82 (1.34–2.48) | <0.001 | 1.12 (0.75–1.68) | 0.576 |

| High come (≥1000 cedis/month) | 8.36 (231) | 2.45 (1.80–3.33) | <0.001 | 1.42 (0.94–2.12) | 0.093 |

| Sexual orientation | |||||

| Gay | 40.83 (1228) | REF | REF | ||

| Bisexual | 48.61 (1343) | 0.99(0. 84–1.16) | 0.883 | 1.05 (0.88–1.26) | 0.580 |

| Transgender | 0.22 (6) | 4.11 (0.48–35.30) | 0.198 | 3.44 (0.36–33.19) | 0.286 |

| Other | 10.35 (286) | 0.75 (0.57–0.97) | 0.027 | 0.87 (0.66–1.16) | 0.352 |

| Type of anal sexual intercourse | |||||

| Versatile sex | 29.93 (827) | REF | REF | ||

| Receptive sex | 23.42 (647) | 1.08 (0.88–1.33) | 0.460 | 1.02 (0.81–1.29) | 0.845 |

| Insertive sex | 46.65 (1286) | 0.72 (0.60–0.86) | <0.001 | 0.75 (0.62–0.91) | 0.004 |

| Bought sex from a male in the past six months | |||||

| Yes | 19.00 (525) | REF | REF | ||

| No | 10.13 (280) | 0.42 (0.31–0.56) | <0.001 | 0.74 (0.52–1.05) | 0.087 |

| Do not buy sex | 70.87 (1958) | 0.60 (0.50–0.73) | <0.001 | 0.86 (0.67–1.09) | 0.198 |

| Sold sex to a male in the past six months | |||||

| Yes | 29.64 (819) | REF | REF | ||

| No | 13.86 (383) | 0.44 (0.34–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.67 (0.50–0.90) | 0.007 |

| Do not sell sex | 56.50 (1561) | 0.80 (0.68–0.96) | 0.013 | 0.83 (0.68–1.01) | 0.068 |

| Alcohol intake | |||||

| Abstainers | 74.05 (2046) | REF | REF | ||

| Light drinkers | 20.05 (554) | 1.54 (1.27–1.87) | <0.001 | 1.28 (1.04–1.58) | 0.020 |

| Moderate drinkers | 4.02 (111) | 1.14 (0.78–1.68) | 0.499 | 1.07 (0.71–1.63) | 0.735 |

| Heavy drinkers | 1.88 (52) | 1.28 (0.73–2.23) | 0.391 | 1.18 (0.65–2.17) | 0.583 |

| Knowledge of HIV | |||||

| No | 33.26 (919) | REF | REF | ||

| Yes | 66.74 (1844) | 1.46 (1.24–1.71) | <0.001 | 1.50 (1.26–1.78) | <0.001 |

| Condom use at last sex with regular/main male partner | |||||

| Yes | 60.98 (1685) | REF | REF | ||

| No | 28.59 (790) | 0.48 (0.40–0.57) | <0.001 | 0.57 (0.47–0.70) | <0.001 |

| Do not have a main/regular male partner | 10.42 (288) | 0.86 (0.67–1.10) | 0.233 | 0.88 (0.67–1.16) | 0.370 |

| HIV test results | |||||

| Negative | 83.24 (2300) | REF | REF | ||

| Positive | 16.76 (463) | 0.33 (0.26–0.41) | <0.001 | 0.40 (0.31–0.51) | <0.001 |

| Number of times forced to have sex within the past 12 months | |||||

| No history of forced sex | 97.14 (2684) | REF | |||

| One or more times | 2.86 (79) | 1.57 (0.98–2.50) | 0.059 | ||

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Atakorah-Yeboah Junior, K.; Phalane, E.; Agyarko-Poku, T.; Atuahene, K.; Shiferaw, Y.A.; Phaswana-Mafuya, R.N. Determinants of HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Insights from the Ghana Men’s Study II. Sexes 2025, 6, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040056

Atakorah-Yeboah Junior K, Phalane E, Agyarko-Poku T, Atuahene K, Shiferaw YA, Phaswana-Mafuya RN. Determinants of HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Insights from the Ghana Men’s Study II. Sexes. 2025; 6(4):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040056

Chicago/Turabian StyleAtakorah-Yeboah Junior, Kofi, Edith Phalane, Thomas Agyarko-Poku, Kyeremeh Atuahene, Yegnanew Alem Shiferaw, and Refilwe Nancy Phaswana-Mafuya. 2025. "Determinants of HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Insights from the Ghana Men’s Study II" Sexes 6, no. 4: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040056

APA StyleAtakorah-Yeboah Junior, K., Phalane, E., Agyarko-Poku, T., Atuahene, K., Shiferaw, Y. A., & Phaswana-Mafuya, R. N. (2025). Determinants of HIV Testing Among Men Who Have Sex with Men in Ghana: Insights from the Ghana Men’s Study II. Sexes, 6(4), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6040056