Healthcare Access for Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Narrative Review of Barriers and Enabling Factors

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Health Care in Malaysia

1.2. Health of Transgender Women in Malaysia

2. Methodology

Reflexivity and Positionality

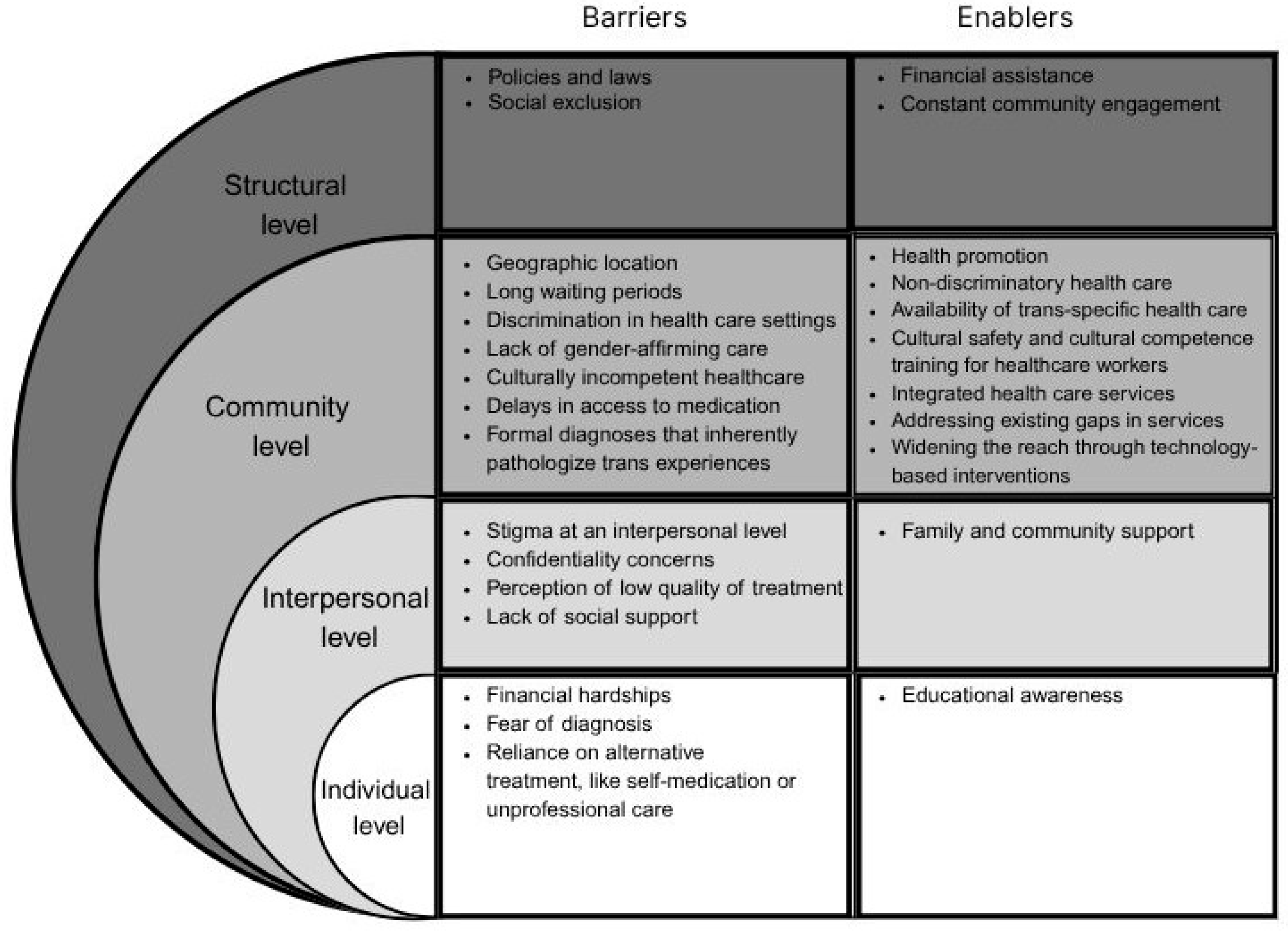

3. Barriers to Healthcare Access and Utilization by Transgender Women in Malaysia

3.1. Primary Healthcare

3.2. Sexual Healthcare

3.3. Oral Healthcare

3.4. Mental Healthcare

4. Enabling Factors of Healthcare Access and Utilization by Transgender Women Malaysia

4.1. Inclusivity Training for Healthcare Workers

4.2. Prioritizing Trans-Specific Health Needs

4.3. Engagement Through Community-Led Organizations

4.4. Healthcare Policy Reforms

4.5. Technology-Based Health Interventions

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| UHC | Universal Health Coverage |

| LMICs | Low- and Middle-Income Countries |

| LGBT | Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, and Transgender |

| MSM | Men who have Sex with Men |

| HIV | Human Immunodeficiency Virus |

| STI | Sexually Transmitted Infections |

| ART | Anti-retroviral Therapy |

| OHRQoL | Oral Health-Related Quality of Life |

| NSPEA | National Strategic Plan for Ending AIDS |

| AIDS | Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome |

| PrEP | Pre-exposure Prophylaxis |

References

- Lutfiyya, M.N.; Gross, A.J.; Soffe, B.; Lipsky, M.S. Dental care utilization: Examining the associations between health services deficits and not having a dental visit in past 12 months. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Lo, Y.-R. World Health Day 2018—Lessons from Malaysia on Universal Health Coverage. Available online: https://www.who.int/malaysia/news/detail/18-04-2018-world-health-day-2018-lessons-from-malaysia-on-universal-health-coverage (accessed on 26 March 2023).

- Ravindran, T.K.S.; Govender, V. Sexual and reproductive health services in universal health coverage: A review of recent evidence from low- and middle-income countries. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1779632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd Noh, S.N.; Jawahir, S.; Tan, Y.R.; Ab Rahim, I.; Tan, E.H. The Health-Seeking Behavior among Malaysian Adults in Urban and Rural Areas Who Reported Sickness: Findings from the National Health and Morbidity Survey (NHMS) 2019. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2022, 19, 3193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quek, D. The Malaysian Healthcare System: A Review. In Proceedings of the Intensive Workshop on Health Systems in Transition, Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 29–30 April 2009; pp. 29–30. [Google Scholar]

- Jaafar, S.; Noh, K.M.; Muttalib, K.A.; Othman, N.H.; Healy, J.; Maskon, K.; Abdullah, A.R.; Zainuddin, J.; Bakar, A.A.; Rahman, S.S.A.; et al. Malaysia Health System Review; Health Systems in Transition; WHO Regional Office for the Western Pacific: Manila, Philippines, 2013; Volume 3. [Google Scholar]

- Shahar, S.; Vanoh, D.; Mat Ludin, A.F.; Singh, D.K.A.; Hamid, T.A. Factors associated with poor socioeconomic status among Malaysian older adults: An analysis according to urban and rural settings. BMC Public Health 2019, 19, 549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Telang, L.A.; Daud, H.S.; Rashid, A.; Cotter, A.G. Exploring the barriers and enablers of oral health care utilisation and safe oral sex practices among transgender women in Malaysia: A qualitative study. BMC Public Health 2025, 25, 1261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afiqah, S.N.; Rashid, A.; Iguchi, Y. Transition experiences of the Malay Muslim Trans women in Northern Region of Malaysia: A qualitative study. Dialogues Health 2022, 1, 100033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barmania, S.; Aljunid, S.M. Transgender women in Malaysia, in the context of HIV and Islam: A qualitative study of stakeholders’ perceptions. BMC Int. Health Hum. Rights 2017, 17, 30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, B.A.; Brown, S.E.; Rutledge, R.; Wickersham, J.A.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Altice, F.L. Gender identity, healthcare access, and risk reduction among Malaysia’s mak nyah community. Glob. Public Health 2016, 11, 1010–1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Human Rights Commission of Malaysia (SUHAKAM). Study on Discrimination Against Transgender Persons Based in Kuala Lumpur and Selangor (Right to Education, Employment, Healthcare, Housing and Dignity); SUHAKAM: Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 2019; Available online: https://www.suhakam.org.my (accessed on 30 May 2025).

- Hughto, J.M.W.; Reisner, S.L.; Pachankis, J.E. Transgender stigma and health: A critical review of stigma determinants, mechanisms, and interventions. Soc. Sci. Med. 2015, 147, 222–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Human Rights Watch. “I’m Scared to Be a Woman”: Human Rights Abuses against Transgender People in Malaysia; Human Rights Watch: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Available online: https://www.hrw.org/report/2014/09/25/im-scared-be-woman/human-rights-abuses-against-transgender-people-malaysia (accessed on 20 April 2025).

- Fazli Khalaf, Z.; Liow, J.W.; Nalliah, S.; Foong, A.L.S. When health intersects with gender and sexual diversity: Medical students’ attitudes towards LGBTQ patients. J. Homosex. 2023, 70, 1763–1786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liaw, J.; Tharumaraj, J.N. Exploring Factors Behind the Lack of Formal Employment Opportunities among Selected Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Preliminary Study. Asia-Pac. J. Futures Educ. Soc. 2023, 2, 43–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, C.J.; Wickersham, J.A.; Altice, F.L.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Khoshnood, K.; Gibson, B.A.; Khati, A.; Maviglia, F.; Shrestha, R. Prevalence and correlates of active amphetamine-type stimulant use among female sex workers in Malaysia. Front. Psychiatry 2022, 13, 879479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Lim, S.H.; Gibson, B.A.; Azwa, I.; Guadamuz, T.E.; Altice, F.L.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Wickersham, J.A. Correlates of newly diagnosed HIV infection among cisgender women sex workers and transgender women sex workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. Int. J. STD AIDS 2021, 32, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rashid, A.; Afiqah, S.N. Depression, anxiety, and stress among the Malay Muslim transgender women in northern Malaysia: A mixed-methods study. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2023, 44, 1124–1132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poteat, T.; Wirtz, A.L.; Radix, A.; Borquez, A.; Silva-Santisteban, A.; Deutsch, M.B.; Khan, S.I.; Winter, S.; Operario, D. HIV risk and preventive interventions in transgender women sex workers. Lancet 2015, 385, 274–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.H.; Lee, K.W.; Cheong, Z.W. Current research involving LGBTQ people in Malaysia: A scoping review informed by a health equity lens. J. Popul. Soc. Stud. 2021, 29, 622–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zay Hta, M.K.; Tam, C.L.; Au, S.Y.; Yeoh, G.; Tan, M.M.; Lee, Z.Y.; Yong, V.V. Barriers and facilitators to professional mental health help-seeking behavior: Perspective of Malaysian LGBT individuals. J. LGBT Issues Couns. 2021, 15, 38–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bauer, G.R.; Hammond, R.; Travers, R.; Kaay, M.; Hohenadel, K.M.; Boyce, M. I don’t think this is theoretical; this is our lives: How erasure impacts health care for transgender people. J. Assoc. Nurses AIDS Care 2009, 20, 348–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Logie, C.H.; Lacombe-Duncan, A.; Brien, N.; Jones, N.; Lee-Foon, N.; Levermore, K.; Marshall, A.; Nyblade, L.; Newman, P.A. Barriers and facilitators to HIV testing among young men who have sex with men and transgender women in Kingston, Jamaica: A qualitative study. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Snelgrove, J.W.; Jasudavisius, A.M.; Rowe, B.W.; Head, E.M.; Bauer, G.R. “Completely out-at-sea” with “two-gender medicine”: A qualitative analysis of physician-side barriers to providing healthcare for transgender patients. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2012, 12, 110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poteat, T.; German, D.; Kerrigan, D. Managing uncertainty: A grounded theory of stigma in transgender health care encounters. Soc. Sci. Med. 2013, 84, 22–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lerner, J.E.; Robles, G. Perceived barriers and facilitators to health care utilization in the United States for transgender people: A review of recent literature. J. Health Care Poor Underserved 2017, 28, 127–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bockting, W.; Robinson, B.; Benner, A.; Scheltema, K. Patient satisfaction with transgender health services. J. Sex Marital Ther. 2004, 30, 277–294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz, T.M. Assessing access to care for transgender and gender nonconforming people: A consideration of diversity in combating discrimination. Soc. Sci. Med. 2014, 110, 65–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Draman, S.; Maliya, S.; Syaffiq, M.; Hamizah, Z.; Razman, M. Mak Nyahs and sex reassignment surgery—A qualitative study from Pahang, Malaysia. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 2019, 18, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheah, E. Monitoring Report: LGBTQ+ Rights in Malaysia. Asian-Pacific Resource & Research Centre for Women (ARROW). 2020. Available online: https://arrow.org.my/wp-content/uploads/2021/01/LGBTIQ-Rights-in-Malaysia-.pdf (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- Asia Pacific Transgender Network (APTN). Legal Gender Recognition in Malaysia: A Legal & Policy Review in the Context of Human Rights; Asia Pacific Transgender Network: Bangkok, Thailand, 2017; Available online: https://www.weareaptn.org/resource/legal-gender-recognition-in-malaysia-a-legal-and-policy-review-in-the-context-of-human-rights/ (accessed on 7 February 2025).

- Draman, S.; Maliya, S.; Farhan, A.; Syazwan, S.; Nur‘Atikah, A.; Abd Aziz, K. Hormone consumption among Mak Nyahs in Kuantan Town: A preliminary survey. IIUM Med. J. Malays. 2018, 17, 63–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashid, A.; Afiqah, S.N.; Iguchi, Y. Use of Hormones Among Trans Women in the West Coast of Peninsular Malaysia: A Mixed Methods Study. Transgend. Health 2021, 6, 114–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, H.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Wickersham, J.A.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Desai, M.M.; John, J.; Altice, F.L. An assessment of health-care students’ attitudes toward patients with or at high risk for HIV: Implications for education and cultural competency. AIDS Care 2014, 26, 1223–1228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, R. P4.28 Stigma and Discrimination Experiences in Health Care Settings More Evident among Transgender People than Males Having Sex with Males (MSM) in Indonesia, Malaysia, the Philippines and Timor Leste: Key Results. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2017, 93 (Suppl. 2), A83–A84. [Google Scholar]

- Vijay, A.; Earnshaw, V.A.; Tee, Y.C.; Pillai, V.; White Hughto, J.M.; Clark, K.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Altice, F.L.; Wickersham, J.A. Factors associated with medical doctors’ intentions to discriminate against transgender patients in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 61–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suleiman, A.; Tze, C.P. The Global AIDS Monitoring Report 2021—Country Progress Report: Malaysia; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2021. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Laporan/Umum/20211130_MYS_country_report_2021.pdf (accessed on 10 March 2024).

- Suleiman, A.; Ramly, M.; Hafad, F.S.A.; Chandrasekaran, S. Integrated Biological and Behavioral Surveillance Survey 2017; Ministry of Health Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2017. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Laporan/Umum/Laporan_Kajian_IBBS_2017.pdf (accessed on 30 January 2025).

- Wickersham, J.A.; Gibson, B.A.; Bazazi, A.R.; Pillai, V.; Pedersen, C.J.; Meyer, J.P.; El-Bassel, N.; Mayer, K.H.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Altice, F.L. Prevalence of human immunodeficiency virus and sexually transmitted infections among cisgender and transgender women sex workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia: Results from a respondent-driven sampling study. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2017, 44, 663–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjit, Y.S.; Gibson, B.A.; Altice, F.L.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Azwa, I.; Wickersham, J.A. HIV care continuum among cisgender and transgender women sex workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. AIDS Care 2021, 34, 784–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rutledge, R.; Morozova, O.; Gibson, B.A.; Altice, F.L.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Wickersham, J.A. Correlates of recent HIV testing among transgender women in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. LGBT Health 2018, 5, 484–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lim, S.C.; Yap, Y.C.; Barmania, S.; Govender, V.; Danhoundo, G.; Remme, M. Priority-setting to integrate sexual and reproductive health into universal health coverage: The case of Malaysia. Sex. Reprod. Health Matters 2020, 28, 1842153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chong, S.; Hollingshead, B.; Lim, S.; Bourne, A. A scoping review of sexual transmission related HIV research among key populations in Malaysia: Implications for interventions across the HIV care cascade. Glob. Public Health 2021, 16, 1014–1027. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, E.G.; Culbert, G.J.; Wickersham, J.A.; Marcus, R.; Steffen, A.D.; Pauls, H.A.; Westergaard, R.P.; Lee, C.K.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Altice, F.L. Physician decisions to defer antiretroviral therapy in key populations: Implications for reducing human immunodeficiency virus incidence and mortality in Malaysia. Open Forum Infect. Dis. 2017, 4, ofw219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Tan, E.H.; Jawahir, S.; Mohd Hanafiah, A.N.; Mohd Yunos, M.H. Demographic and socioeconomic inequalities in oral healthcare utilisation in Malaysia: Evidence from a national survey. BMC Oral Health 2021, 21, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mohd, F.N.; Said, A.H.; Ali, A.; Draman, W.L.S.; Aznan, M.; Aris, M. Oral Health Related Quality of Life Among Transgender Women in Malaysia. Alcohol 2020, 47, 475. Available online: http://irep.iium.edu.my/id/eprint/87879 (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Ho, S.H.; Shamsudin, A.H.; Liow, J.W.; Juhari, J.A.; Ling, S.A.; Tan, K. Mental Healthcare Needs and Experiences of LGBT+ Individuals in Malaysia: Utility, Enablers, and Barriers. Healthcare 2024, 12, 998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alibudbud, R. The prevalence and associated factors of mental health conditions among transgender people in Southeast Asia: A systematic review. Int. J. Ment. Health 2025, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, K.K.; Ling, S.A. Cultural safety for LGBTQIA+ people: A narrative review and implications for health care in Malaysia. Sexes 2022, 3, 385–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. Cultural Competence in Transgender Healthcare. In Advancing Equity—Health, Rights, and Representation in LGBTQ+ Communities; Leung, E., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walch, S.E.; Sinkkanen, K.A.; Swain, E.M.; Francisco, J.; Breaux, C.A.; Sjoberg, M.D. Using Intergroup Contact Theory to Reduce Stigma Against Transgender Individuals: Impact of a Transgender Speaker Panel Presentation. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 2012, 42, 2583–2605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SEED Malaysia and Galen Centre for Health and Social Policy. Practical Guidelines for Trans-Specific Primary Health Care in Malaysia. 2020. Available online: https://galencentre.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/Final-Practical-Guidelines-for-Trans-Specific-PHC.pdf (accessed on 17 April 2024).

- Coleman, E.; Radix, A.E.; Bouman, W.P.; Brown, G.R.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Deutsch, M.B.; Ettner, R.; Fraser, L.; Goodman, M.; Green, J.; et al. Standards of Care for the Health of Transgender and Gender Diverse People, Version 8. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2022, 23, S1–S259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Health Malaysia. National Strategic Plan on Ending AIDS (NSPEA) 2016–2030. 2015. Available online: https://www.aidsdatahub.org/sites/default/files/resource/malaysia-national-strategic-plan-ending-aids-2016-2030.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2024).

- Chandrasekaran, S.; Aziz, N.; Ellan, P. An innovative approach for engaging key populations in HIV continuum of care in Malaysia. STI friendly clinic by the Ministry of Health, Malaysia. J. AIDS Clin. Res. 2017, 8 (Suppl. 9), 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maoto, M.; Davis, B. Breaking Barriers: How Transwomen Meet Their Healthcare Needs. Afr. J. Prim. Health Care Fam. Med. 2024, 16, 4598. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/10520/ejc-phcfm_v16_n1_a4598 (accessed on 2 May 2024). [CrossRef]

- Wan Mohamad Darani, W.N.S.; Chen, X.W.; Samsudin, E.Z.; Mohd Nor, F.; Ismail, I. Determinants of Successful Human Immunodeficiency Virus Treatment Outcomes: A Linkage of National Data Sources in Malaysia. Malays. J. Med. Sci. 2023, 30, 172–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institute of HIV Research and Innovation (IHRI). Tangerine Community Health Clinic. Available online: https://ihri.org/tangerine/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- LoveYourself. Available online: https://loveyourself.ph/trans-health/ (accessed on 2 June 2025).

- Janamnuaysook, R.; Taesombat, R.; Wong, J.; Vannakit, R.; Mills, S.; van der Loeff, M.S.; Reiss, P.; van Griensven, F. Innovating Healthcare: Tangerine Clinic’s Role in Implementing Inclusive and Equitable HIV Care for Transgender People in Thailand. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2024, 28, e26405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eustaquio, P.C.; Castelo, A.V.; Araña, Y.S.; Corciega, J.O.L.; Rosadiño, J.D.T.; Pagtakhan, R.G.; Regencia, Z.J.G.; Baja, E.S. Prevalence and Factors Associated with Gender-Affirming Surgery among Transgender Women & Transgender Men in a Community-Based Clinic in Metro Manila, Philippines: A Retrospective Study. Sex. Med. 2022, 10, 100497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- van Griensven, F.; Janamnuaysook, R.; Nampaisan, O.; Peelay, J.; Samitpol, K.; Mills, S.; Pankam, T.; Ramautarsing, R.; Teeratakulpisarn, N.; Phanuphak, P. Uptake of primary care services and HIV and syphilis infection among transgender women attending the Tangerine Community Health Clinic, Bangkok, Thailand, 2016–2019. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2021, 24, e25683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sevelius, J.M.; Deutsch, M.B.; Grant, R. The future of PrEP among transgender women: The critical role of gender affirmation in research and clinical practices. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2016, 19, 21105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tharmalingam, D. PrEP Initiatives in Malaysia. APCOM. 23 July 2021. Available online: https://www.apcom.org/prep-initiatives-in-malaysia/ (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Winter, S.; Diamond, M.; Green, J.; Karasic, D.; Reed, T.; Whittle, S.; Wylie, K. Transgender people: Health at the margins of society. Lancet 2016, 388, 390–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lall, P.; Shaw, S.A.; Saifi, R.; Sherman, S.G.; Azmi, N.N.; Pillai, V.; El-Bassel, N.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Wickersham, J.A. Acceptability of a microfinance-based empowerment intervention for transgender and cisgender women sex workers in Greater Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia. J. Int. AIDS Soc. 2017, 20, 21723. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ayub, N. Gender Identity. Women’s Tribunal Malaysia 2021 Final Report. 2021. Available online: https://www.womenstribunalreport.com/genderidentity (accessed on 13 May 2025).

- Ministry of Health, Malaysia. Health White Paper for Malaysia. 2023. Available online: https://www.moh.gov.my/moh/resources/Penerbitan/Penerbitan%20Utama/Kertas%20Putih%20Kesihatan/Kertas_Putih_Kesihatan_(ENG)_compressed.pdf (accessed on 15 May 2025).

- Ghosh, A. The Politics of Alignment and the ‘Quiet Transgender Revolution’ in Fortune 500 Corporations, 2008 to 2017. Socio-Econ. Rev. 2021, 19, 1095–1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A. The Global LGBT Workplace Equality Movement. In Companion to Sexuality Studies; Naples, N.A., Ed.; John Wiley & Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2020; pp. 445–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, A.; Weikum, D.; Cravero, C.; Kamarulzaman, A.; Altice, F.L. Assessing mobile technology use and mHealth acceptance among HIV-positive men who have sex with men and transgender women in Malaysia. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0248705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Department of Statistics Malaysia. ICT Use and Access by Individuals and Households Survey Report, Malaysia; Department of Statistics Malaysia: Putrajaya, Malaysia, 2022. Available online: https://www.dosm.gov.my/site/downloadrelease?id=ict-use-and-access-by-individuals-and-households-survey-report-malaysia-2021&lang=English (accessed on 23 June 2023).

- Shrestha, R. Improving HIV Testing and PrEP for Transgender Women Through mHealth (MyLink2Care). National Institutes of Health (NIH), R21AI157857, 28 April 2021–31 March 2024. Available online: https://reporter.nih.gov/search/-wx5W2Ox9EuklcP3UwekrQ/project-details/10398983 (accessed on 29 June 2024).

- Telang, L.A.; Daud, H.S.; Cotter, A.G.; Rashid, A. Ms Radiance: A community-led social media mHealth pilot for transgender women. Int. J. Transgend. Health 2025, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saadat, M.; Keramat, A.; Jahanfar, S.; Nazari, A.M.; Ranjbar, H.; Motaghi, Z. A social-ecological approach to exploring barriers in accessing sexual and reproductive healthcare services among Iranian transgender women. HIV AIDS Rev. 2024, 22, 76–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reisner, S.L.; Poteat, T.; Keatley, J.; Cabral, M.; Mothopeng, T.; Dunham, E.; Holland, C.E.; Max, R.; Baral, S.D. Global health burden and needs of transgender populations: A review. Lancet 2016, 388, 412–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Telang, L.A.; Cotter, A.G.; Rashid, A. Healthcare Access for Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Narrative Review of Barriers and Enabling Factors. Sexes 2025, 6, 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030050

Telang LA, Cotter AG, Rashid A. Healthcare Access for Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Narrative Review of Barriers and Enabling Factors. Sexes. 2025; 6(3):50. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030050

Chicago/Turabian StyleTelang, Lahari A., Aoife G. Cotter, and Abdul Rashid. 2025. "Healthcare Access for Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Narrative Review of Barriers and Enabling Factors" Sexes 6, no. 3: 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030050

APA StyleTelang, L. A., Cotter, A. G., & Rashid, A. (2025). Healthcare Access for Transgender Women in Malaysia: A Narrative Review of Barriers and Enabling Factors. Sexes, 6(3), 50. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030050