Treatment of Irregular Uterine Bleeding Caused by Progestin-Only Contraceptives: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Design

2.2. Searching Process

2.3. Study Eligibility

2.4. Data Extraction

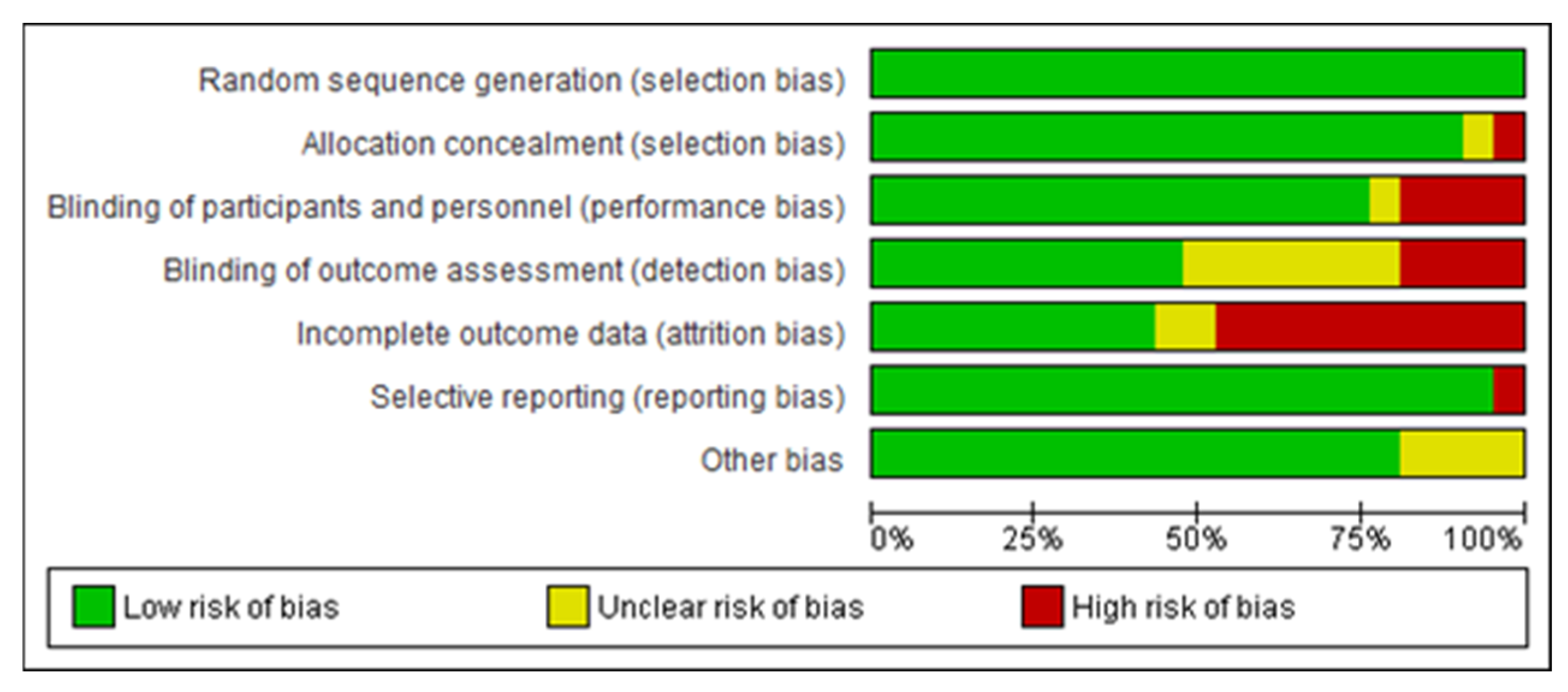

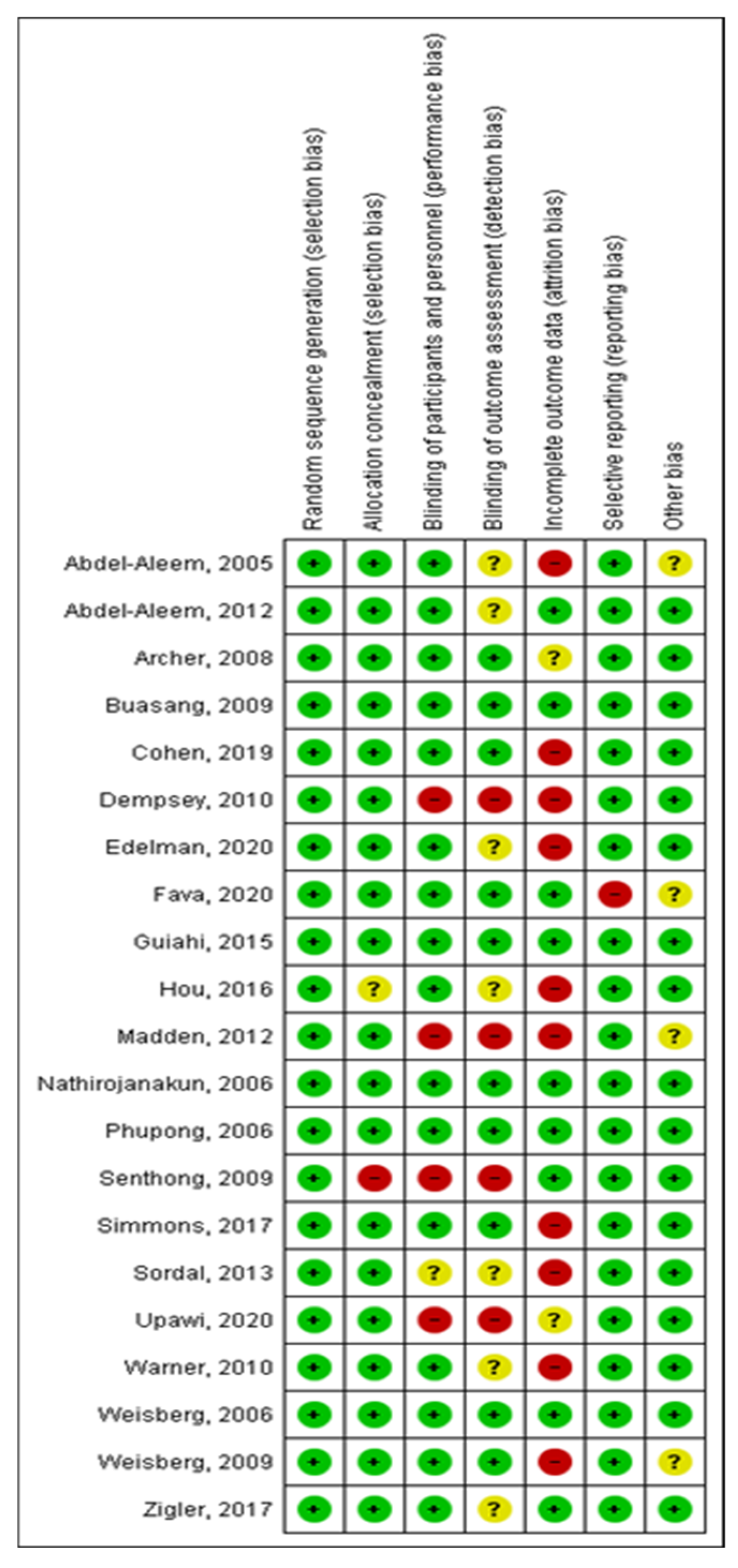

2.5. Methodological Quality Assessment

3. Results

3.1. Non-Steroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs (NSAIDs)

3.2. Selective Estrogen Receptor Modulator (Tamoxifen)

3.3. Antifibrinolytics

3.4. Antibiotics, Matrix Metalloproteinase Inhibitors

3.5. Selective Progesterone Receptor Modulator (SPRM)—UPA Versus Placebo

3.6. Combined Contraceptives (COCP)

3.7. Progesterone Receptor Antagonists

3.8. Participant Satisfaction

3.9. Adverse Effects

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| DMPA | Medroxyprogesterone acetate |

| LNG | Levonorgestrel |

| ENG | Etonogestrel |

| EE | Ethinylestradiol |

| LNG-IUD | Levonorgestrel intrauterine devices |

| LNG-IUS | Levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system |

| LARC | Long-acting reversible contraception methods |

| IUD | Intrauterine devices |

| IUS | Intrauterine system |

| SERM | Selective estrogen receptor modulators |

| SPRM | Selective progesterone receptor modulator |

| CDB-2914 | Ulipristal acetato |

| UPA | Ulipristal acetate |

| NSAIDs | Non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs |

| COCs | Combined contraceptives |

| COCPs | Combined oral contraceptive pills |

| POPs | Progestin-only pills |

| OCPs | Oral contraceptive pills |

| S/B | Spotting/bleeding |

| BMI | Body mass index |

| RCT | Randomized clinical trial |

| FIGO | International Federation of Gynecology and Obstetrics |

References

- Amiri, M.; Tehrani, F.R.; Nahidi, F.; Kabir, A.; Azizi, F. Comparing the effects of combined oral contraceptives containing progestins with low androgenic and antiandrogenic activities on the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis in patients with polycystic ovary syndrome: Systematic review and meta-analysis. JMIR Res. Protoc. 2018, 7, e9024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Słopień, R.; Milewska, E.; Rynio, P.; Męczekalski, B. Use of oral contraceptives for management of acne vulgaris and hirsutism in women of reproductive and late reproductive age. Menopause Rev. Przegląd Menopauzalny 2018, 17, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Steinberg, J.R.; Marthey, D.; Xie, L.; Boudreaux, M. Contraceptive method type and satisfaction, confidence in use, and switching intentions. Contraception 2021, 104, 176–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leelakanok, N.; Methaneethorn, J. A systematic review and meta-analysis of the adverse effects of levonorgestrel emergency oral contraceptive. Clin. Drug Investig. 2020, 40, 395–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zigler, R.E.; McNicholas, C. Unscheduled vaginal bleeding with progestin-only contraceptive use. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2017, 216, 443–450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bastianelli, C.; Farris, M.; Bruni, V.; Rosato, E.; Brosens, I.; Benagiano, G. Effects of progestin-only contraceptives on the endometrium. Expert Rev. Clin. Pharmacol. 2020, 13, 1103–1123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lasa, I.L.; Merino, S.G.; Mesa, J.M.M. Manejo clínico del sangrado producido con la utilización de métodos anticonceptivos con sólo gestágenos [Clinical management of progestin only method’s bleeding pattern]. Rev. Iberoam. Fert. Rep. Hum. 2011, 28, 155–159. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, L.M.; Ramesh, S.; Chen, M.; Edelman, A.; Otterness, C.; Trussell, J.; Helmerhorst, F.M. Progestin-only contraceptives: Effects on weight. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, CD008815. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bosanac, S.S.; Trivedi, M.; Clark, A.K.; Sivamani, R.K.; Larsen, L.N. Progestins and acne vulgaris: A review. Dermatol. Online J. 2018, 24, 13030/qt6wm945xf. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, K.H.; Zirwas, M.J. Contraception and the dermatologist. J. Am. Acad. Dermatol. 2013, 68, 1022–1029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Higgins, J.P.T.; Thomas, J.; Chandler, J.; Cumpston, M.; Li, T.; Page, M.J.; Welch, V.A. (Eds.) Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Kahale, L.A.; Elkhoury, R.; El Mikati, I.; Pardo-Hernandez, H.; Khamis, A.M.; Schünemann, H.J.; Haddaway, N.R.; Akl, E.A. Tailored PRISMA 2020 flow diagrams for living systematic reviews: A methodological survey and a proposal. F1000Research 2021, 10, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. The PRISMA 2020 statement: An updated guideline for reporting systematic reviews. Int. J. Surg. 2021, 88, 105906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munro, M.G.; Critchley, H.O.D.; Broder, M.S.; Fraser, I.S. Disorders FWG on M. FIGO classification system (PALM-COEIN) for causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in nongravid women of reproductive age. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2011, 113, 3–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; Shaaban, O.M.; Amin, A.F.; Abdel-Aleem, A.M. Tamoxifen treatment of bleeding irregularities associated with Norplant use. Contraception 2005, 72, 432–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edelman, A.B.; Kaneshiro, B.; Simmons, K.B.; Hauschildt, J.L.; Bond, K.; Boniface, E.R.; Jensen, J.T. Treatment of Unfavorable Bleeding Patterns in Contraceptive Implant Users: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2020, 136, 323–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fava, M.; Peloggia, A.; Baccaro, L.F.; Castro, S.; Carvalho, N.; Bahamondes, L. A randomized controlled pilot study of ulipristal acetate for abnormal bleeding among women using the 52-mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2020, 149, 10–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Upawi, S.N.; Ahmad, M.F.; Abu, M.A.; Ahmad, S. Management of bleeding irregularities among etonogestrel implant users: Is combined oral contraceptives pills or nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs the better option? J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Res. 2020, 46, 479–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sørdal, T.; Inki, P.; Draeby, J.; O’Flynn, M.; Schmelter, T. Management of initial bleeding or spotting after levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system placement: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2013, 121, 934–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madden, T.; Proehl, S.; Allsworth, J.E.; Secura, G.M.; Peipert, J.F. Naproxen or estradiol for bleeding and spotting with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system: A randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 2012, 206, 129.e1–129.e8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warner, P.; Guttinger, A.; Glasier, A.F.; Lee, R.J.; Nickerson, S.; Brenner, R.M.; Critchley, H.O.D. Randomized placebo-controlled trial of CDB-2914 in new users of a levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system shows only short-lived amelioration of unscheduled bleeding. Hum. Reprod. 2010, 25, 345–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, M.A.; Simmons, K.B.; Edelman, A.B.; Jensen, J.T. Tamoxifen for the prevention of unscheduled bleeding in new users of the levonorgestrel 52-mg intrauterine system: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2019, 100, 391–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; Shaaban, O.M.; Abdel-Aleem, M.A.; Fetih, G.N. Doxycycline in the treatment of bleeding with DMPA: A double-blinded randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2012, 86, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buasang, K.; Taneepanichskul, S. Efficacy of Celecoxib on Controlling Irregular Uterine Bleeding Secondary to Jadelle (R) Use. Med. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2009, 92, 301. [Google Scholar]

- Nathirojanakun, P.; Taneepanichskul, S.; Sappakitkumjorn, N. Efficacy of a selective COX-2 inhibitor for controlling irregular uterine bleeding in DMPA users. Contraception 2006, 73, 584–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dempsey, A.; Roca, C.; Westhoff, C. Vaginal estrogen supplementation during Depo-Provera initiation: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2010, 82, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senthong AJaree Taneepanichskul, S. The effect of tranexamic acid for treatment irregular uterine bleeding secondary to DMPA use. Med. J. Med. Assoc. Thail. 2009, 92, 461. [Google Scholar]

- Simmons, K.B.; Edelman, A.B.; Fu, R.; Jensen, J.T. Tamoxifen for the treatment of breakthrough bleeding with the etonogestrel implant: A randomized controlled trial. Contraception 2017, 95, 198–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisberg, E.; Hickey, M.; Palmer, D.; O’Connor, V.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Findlay, J.K.; Fraser, I.S. A randomized controlled trial of treatment options for troublesome uterine bleeding in Implanon users. Hum. Reprod. 2009, 24, 1852–1861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Guiahi, M.; McBride, M.; Sheeder, J.; Teal, S. Short-term treatment of bothersome bleeding for etonogestrel implant users using a 14-day oral contraceptive pill regimen: A randomized controlled trial. Obstet. Gynecol. 2015, 126, 508–513. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, M.Y.; McNicholas, C.; Creinin, M.D. Combined oral contraceptive treatment for bleeding complaints with the etonogestrel contraceptive implant: A randomised controlled trial. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care 2016, 21, 361–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phupong, V.; Sophonsritsuk, A.; Taneepanichskul, S. The effect of tranexamic acid for treatment of irregular uterine bleeding secondary to Norplant® use. Contraception 2006, 73, 253–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Weisberg, E.; Hickey, M.; Palmer, D.; O’Connor, V.; Salamonsen, L.A.; Findlay, J.K.; Fraser, I.S. A pilot study to assess the effect of three short-term treatments on frequent and/or prolonged bleeding compared to placebo in women using Implanon. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 295–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Archer, D.F.; Philput, C.B.; Levine, A.S.; Cullins, V.; Stovall, T.G.; Bacon, J.; Weber, M.E. Effects of ethinyl estradiol and ibuprofen compared to placebo on endometrial bleeding, cervical mucus and the postcoital test in levonorgestrel subcutaneous implant users. Contraception 2008, 78, 106–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdel-Aleem, H.; d’Arcangues, C.; Vogelsong, K.M.; Gaffield, M.L.; Gülmezoglu, A.M. Treatment of vaginal bleeding irregularities induced by progestin only contraceptives. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013, 10, CD003449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piacenti, I.; Tius, V.; Viscardi, M.F.; Biasioli, A.; Arcieri, M.; Restaino, S.; Muzii, L.; Vizzielli, G.; Porpora, M.G. Dienogest vs. combined oral contraceptive: A systematic review and meta-analysis of efficacy and side effects to inform evidence-based guidelines. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2025, 104, 1424–1432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Munro, M.G.; Critchley, H.O.D.; Fraser, I.S. The two FIGO systems for normal and abnormal uterine bleeding symptoms and classification of causes of abnormal uterine bleeding in the reproductive years: 2018 revisions. Int. J. Gynecol. Obstet. 2018, 143, 393–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Article | Treatment Description/Plan | Primary Outcome(s) | Secondary Outcome(s) Satisfaction and Adverse Effects |

|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel Aleem, 2005 | Two daily oral doses of 10 mg tamoxifen during 10 days -- Two daily oral doses of placebo during 10 days | At the end of the treatment, a high percentage of tamoxifen users reported a stop in the bleeding as compared to the control group (88% and 68%, respectively; p = 0.016). First month: 85.7% vs. 75.5%; second month: 34.7% vs. 23.9%. Difference is statistically significant (p < 0.05). There were no differences between tamoxifen and placebo users in the third month. 30 days after starting the therapy, days with bleeding were 5.0, 4.3, and 3.6 for patients receiving ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively. These differences were not statistically significant. Mean number of days with no bleeding during this period was 1.1, 1.8, and 2.8 for ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively. There was a statistically significant difference between ethinylestradiol and placebo in spotting reduction (p = 0.04). Mean number of days with no bleeding in the first 30 days after ending the treatment was 6.1, 6.2, and 6.4 for ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively, and these results presented no statistically significant differences. | Satisfaction: The beneficial effect of tamoxifen was seen in women’s improved lifestyles and their general satisfaction with the treatment. One and two months after the treatment ended, a significantly higher percentage of tamoxifen users were satisfied with the treatment than in the control group (85.7 and 75.5% versus 34.7% and 23.9%, respectively; p < 0.005). The first group also stated a high performance in their household chores, religious duties, and sex life as compared to the latter group. There were no differences in the third month. Adverse effects: Headache, gastrointestinal disorders, dizziness, easy fatigue, hot flashes. |

| Abdel Aleem, 2012 | An oral dose of 100 mg doxycycline every twelve hours, during 5 days -- Placebo every 12 h, during 5 days | The number of bleeding and spotting days was 14.5 ± 5.1 in the doxycycline group and 13.6 ± 4.6 in the placebo group. This demonstrates that there was no significant difference between the two study groups regarding the primary outcome (women who stopped bleeding within 10 days of starting treatment; 22/34 vs. 25/34 0.88 (0.64, 1.21)) Doxycycline treatment caused no statistically significant differences in the number of bleeding or spotting days in the 3 months following treatment as compared to the placebo group. In the third month following treatment, the mean number of bleeding days was 7.2 ± 4.4 in the doxycycline group, and 7.3 ± 4.6 in the placebo group. The mean number of spotting days was 3.7 ± 2.8 and 3.6 ± 2.7 in the two groups, respectively. The relative risks [RR] of having a bleeding-free interval equal to or less than 15 days in the first 3 months following treatment are summarized. There was no statistically significant difference between the treatment and control groups. In the third month following treatment, RR was 0.90 and 95% CI was 0.64–1.28. | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: Two women in the doxycycline group complained about slight nausea during treatment, while only one in the control group did so. Another patient in the doxycycline group complained about diarrhoea. |

| Archer, 2008 | Daily 20 mcg EE (oral tablet) during 10 days -- Two daily doses of placebo during 5 days — Two daily oral doses of 400 mg ibuprofen during 5 days -- A daily dose of placebo during 10 days | The primary outcome measure was the number of days of vaginal (endometrial) spotting/bleeding (S/B). The mean number of S/B days during Days 1–5 of treatment was 1.1, 1.8 and 1.2 for ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively. These results were not statistically different among groups. From day 6 to day 10, there were no differences found in mean S/B days between treatments: 1.4, 0.9 and 1.0 for ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo, respectively (see Table 2). There were no differences in mean S/B days within each treatment (ethinylestradiol, ibuprofen, and placebo) when days 1–5 were compared to days 6–10. The mean number of S/B days was not different among treatments during days 1 to 15 after initiation of therapy. The mean number of S/B days was not different among treatments during days 1 to 15 after initiation of therapy. | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: No effect on cervical mucus or sperm was found between treatments. |

| Buasang, 2009 | Daily oral dose of 200 mg celecoxib during 5 days -- Daily oral dose of placebo during 5 days | The percentage of subjects whom bleeding was stopped within 7 days after initial treatment was significantly higher in the celecoxib group than in the placebo group (70% vs. 0%; p < 0.001). The mean duration of bleeding-free interval was significantly longer in celecoxib than placebo group (24.0 + 1.65 days vs. 10.0 + 6.50 days; p < 0.001). The mean duration of bleeding days was significantly shorter in celecoxib than placebo group (5.0 + 1.65 vs. 19.0 + 6.50 days; p < 0.001). The mean duration of bleeding-free interval was significantly longer in celecoxib than placebo group (24.0 + 1.65 days vs. 10.0 + 6.50 days; p < 0.001). | Satisfaction: Patients’ satisfaction in the celecoxib group was significantly higher than in the placebo group (80% vs. 30%; p < 0.001). Adverse effects: There was no detectable adverse effect in any group. |

| Cohen, 2019 | Two daily doses of 10 mg tamoxifen during 7 days -- Two daily doses of placebo during 7 days | 40% reduction in B/S days over 30 days Compared to placebo users, participants who received tamoxifen had slightly decreased mean B/S days after initiating study drug (16.8 ± 9.0 days vs. 12 ± 5.8 days, p = 0.08). This equated to mean 4.8 fewer B/S days (95% confidence interval—10.1 to 0.5 days, p = 0.08). | Satisfaction: The study groups reported similar satisfaction with their bleeding patterns. Adverse effects: There were no severe events reported. |

| Dempsey, 2010 | 24.8 mg estradiol acetate (vaginal ring) -- No placebo | For each additional day of bleeding and/or spotting reported, women were 3% less likely to receive a second injection (OR 0.97, 95% CI 0.94–0.99). Those who received a second injection of DMPA had, on average, 15 fewer bleeding days during the first follow-up period than those who discontinued (p = 0.02). | Satisfaction: The majority reported being somewhat or very satisfied with the ring. Adverse effects: Reported side effects, including breast tenderness, nausea, mood swings, headaches, vaginal discharge, weight change, and acne, did not differ between randomization groups. The frequency of these reported side effects also did not predict continuation. |

| Fava, 2020 (rev) | 5 mg ulipristal acetate (pills) during 5 days -- 5 mg placebo during 5 days | The number of days before bleeding stopped and the days free of bleeding were statistically similar between the two groups (p > 0.05), although there was a trend toward fewer days before bleeding stopped (3.3 ± 4.5 days vs. 6.6 ± 8.5 days; p = 0.399) and more days free of bleeding (19.6 ± 14.0 days vs. 11.7 ± 9.5 days; p = 0.177) among users of ulipristal acetate than in users of placebo. Furthermore, 30, 60, and 90 days after initiation of treatment, the mean number of bleeding days was not statistically different between groups (p > 0.05), although there was a trend toward fewer bleeding days among the ulipristal acetate group compared with the placebo group. Endometrial thickness at baseline compared with at 90 days was similar among both treatment groups (4.7 ± 1.2 days vs. 6.2 ± 4.5 days; p = 0.618). One IUS was removed from a participant in the ulipristal acetate group. | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: In general, the main adverse effect reported during the treatment period was headaches. No other adverse events were reported. |

| Guiahi, 2015 | 150 mcg levonorgestrel -- 30 mcg ethinylestradiol -- Two daily doses of placebo during 14 days | Participants randomized to receive OCPs were 11.7 times more likely (95% CI 1.9–70.2) to have a temporary interruption of bleeding during the study drug period: 14 (87.5% ± 16.2%) in the OCP group compared with 6 (37.5% ± 23.7%) in the placebo group (p <0.01). The median number of days to the start of the temporarily interrupted episode (if one occurred) was 5.0 for the intervention group compared with 9.0 for the placebo group (p = 0.05). Regardless of whether a temporary interruption of bleeding was achieved, the median number of days without bleeding during the 14-day therapy period was higher in the treatment group than in the placebo group (9.0 vs. 3.0, p = 0.03). | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: Not reported. |

| Madden, 2012 | Naproxeno 500 mg twice daily x 5 days x 4 week Two daily doses of 500 mg naproxen for the first 5 days of each 4 week period -- Post-insertion patch of 0.1 mg estradiol every week -- Oral placebo | The naproxen group was more likely to be in the lowest quartile of bleeding and spotting days compared with placebo (naproxen: 42.9%, placebo: 16.3%; p = 0.03). The median number of bleeding and spotting days was 27.5 (range: 5–83 days) in the naproxen group, 44 (range: 2–82 days) in the estradiol group, and 32 (range: 9–84 days) in the placebo group. With the use of nonparametric testing, the distribution of bleeding and spotting days was not significantly different in the naproxen group compared with the placebo group (p = 0.15) or in the estradiol group compared with the placebo group (p = 0.10). In the multivariable analysis, the naproxen group had a 10% reduction in bleeding and spotting days (adjusted relative risk: 0.90; 95% CI: 0.84–0.97) compared with placebo. More frequent bleeding and spotting was observed in the estradiol group (adjusted relative risk: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.17–1.34). The administration of naproxen resulted in a reduction in bleeding and spotting days compared with placebo. | Satisfaction: Women in the estradiol group were more likely to be dissatisfied with their bleeding pattern at 4 weeks; 39.5% of the women in the estradiol group were dissatisfied with their bleeding, compared with 9.5% and 11.6% of women in the naproxen and placebo groups, respectively (p = 0.01). Satisfaction with bleeding patterns improved over time in all groups. At 12 weeks, 85% of women reported being “somewhat” or “very” satisfied with their bleeding pattern, and satisfaction did not differ by treatment arm (p = 0.12). Satisfaction with the LNG-IUS was 94% at 12 weeks in all 3 study groups. There were few serious adverse events reported during the treatment period. One participant in the naproxen arm had her LNG-IUS removed because of complaints of chest pain. Adverse effects: Not reported. |

| Madden, 2012 | 3 daily valdecoxib tablets (20 mg) during 5 days -- 2 daily placebo tablets during 5 days | The mean duration of bleeding-free days in a period of 28 days was 17.8 ± 8.2 in the valdecoxib group and 11.5 ± 10.4 days in the placebo group. There were significant differences between both groups (p < 0.05) 77.3% treated with valdecoxib stopped bleeding, whereas 33.3% in the placebo group stopped bleeding within 7 days after the initial treatment. The mean value of the number of treatment days required for stopping the bleeding episode and the mean value for the bleeding-free interval (within 28 days of the follow-up period) in the valdecoxib-treated group were 1.7 ± 0.9 and 18.6 ± 6.0 days, respectively (p > 0.05). | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: Not reported. |

| Phupong, 2006 | 4 daily doses of 2 250 mg tranexamic acid capsules during 5 days -- Same doses of placebo | During the follow-up period (4 weeks after the initiation of the treatment), 58.8% in the tranexamic acid group and 76.5% in the placebo group stopped bleeding (p = 0.12). The percentage of women whose bleeding stopped within 7 days after the initiation of the treatment was significantly higher after tranexamic acid treatment than placebo (64.7% vs. 35.3%, p = 0.015). The mean duration of bleeding and spotting days was not significantly different between the two groups during the 28 days of the follow-up period (mean: 15.4 and 12.7 days, respectively; p = 0.182). | Satisfaction: Not reported Adverse effects: There were no detectable adverse effects in any group. |

| Sordal, 2013 | Three daily oral doses of 500 mg tranexamic acid while bleeding or spotting -- Three daily oral doses of 500 mg mefenamic acid while bleeding or spotting -- Placebo (lactose and magnesium stearate) | The mean value of bleeding or spotting days was lower in the tranexamic acid group than in the mefenamic acid and placebo groups. The mean reduction in bleeding and/or spotting days was 6 days (95% CI: −14.0–1.0; p = 0.049) for the tranexamic acid treatment, and 3 days (95% CI: −11.0–5.0; p = 0.229) for the mefenamic acid treatment. | Satisfaction: There were no significant differences in satisfaction with the use of IUD. In all groups, more than 85% of the women declared to be satisfied. This shows that satisfaction with the studied drug does not influence general satisfaction with the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. Continuation rates after 16 weeks were 96.7%, 96.6%, and 98.3% for the tranexamic acid, mefenamic acid, and placebo groups, respectively. Adverse effects: Gastrointestinal adverse effects were more common in the tranexamic acid group, while headaches were less frequent in the mefenamic acid gorup. Two women from the tranexamic acid group suffered a severe adverse event. One of them had an asymptomatic case of intra-abdominal migration of a copper IUD, which was apparently spontaneously expelled, while the other suffered from endometritis and had to be hospitalized. The endometritis was completely cured with antibiotics and removal of the levonorgestrel intrauterine system. |

| Sethong, 2009 | 4 daily doses of 250 mg tranexamic acid during 5 days -- 4 daily doses of 250 mg placebo during 5 days | Of the subjects, 88% treated with tranexamic acid stopped bleeding, whereas 8.2% in the placebo group stopped bleeding within seven days after initiation of the treatment, thus a significant difference (p < 0.05). The mean bleeding-free interval during 28 days for the tranexamic acid and placebo were 20.6 days and 7.5 days, respectively. This was also a significant difference between the two groups (p < 0.05). | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: Not reported. |

| Warner, 2010 | Daily oral dose of 50 mg progesterone receptor modulator CDB-2914 for three consecutive days, in separate treatments starting 21, 49, and 77 days after LNG-IUS insertion. -- No placebo | After the first treatment, there was a statistically significant difference in bleeding/spotting that favoured CDB-2914, for an amount of 3 days (difference: 210.6%, p = 0.011), but in the 64 days following the third treatment, women from the CDB-2914 group reported more days with bleeding/spotting, at 6 days (±9.5%, p = 0.022). In this last period, the difference in the highest amount of bleeding/spotting-free days was not statistically significant (24 days for CDB-2914 versus 26 days for placebo). During the treatment and follow-up stages (from the 21st to the 166th day), both groups showed a reduction in bleeding/spotting, with a highly significant statistical difference (p = 0.0001). | Satisfaction: Patients’ dissatisfaction with treatment. Vaginal bleeding acceptability was favorable and similar between the two groups, with 92% of each group reporting less bleeding than before insertion (57/60 in the CDB-2914 group, and 48/52 in the placebo group). Some women found that bleeding patterns were “more inconvenient” than before, with a higher percentage of them being in the CDB-2914 group [39% (22/56) versus 19% (9/48); p = 0.036]. Both groups also had favorable and similar responses to general health and heaviness of the latest menstruation as compared to before LNG-IUS. Both groups reported very similar results in the last 4 weeks, experiencing 13 out of the 14 symptoms appearing in the ending questionnaire; however, women from the CDB-2914 group were more likely to declare that “they were liable to gain weight” [23% (14/61) vs. 4% (2/55); 95% CI: 7–32%, p = 0.003]. Adverse effects: Not reported. |

| Weisberg, 2006 | Two doses of 25 mg mifepristone for 1 day + two daily doses of placebo for 4 days -- Two daily doses of 100 mg doxycycline during 5 days -- Two doses of 25 mg mifepristone for 1 day + 2 daily doses of 10 μg ethinylestradiol for 4 days -- Two daily doses of placebo during 5 days | Two active treatment regimens were significantly more effective than placebo in terminating a bleeding episode. Both mifepristone in combination with ethinylestradiol and doxycycline alone were significantly more effective than mifepristone alone or placebo in stopping a bleeding episode. Mifepristone with ethinylestradiol and doxycycline alone were equally effective in stopping bleeding. Mifepristone with ethinylestradiol terminated a bleeding episode after a mean duration of 4.2 days (CI 3.5–5.2), compared to 4.8 days (CI 3.9–5.8) for doxycycline 5.9 days (CI 4.8–7.2) for mifepristone alone, and 7.5 days (CI 6.1–9–1) for placebo. | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: Women in each treatment group reported a wide range of side effects and this did not differ according to the treatment used or between those taking active treatment and those taking placebo. Side effects occurred in 23 women on placebo, 28 women using mifepristone and ethinylestradiol, 19 women using doxycycline, and 21 women using mifepristone alone. These side effects were usually minor and did not result in women stopping treatment. The most common side effect was nausea, occasionally accompanied by vomiting which occurred in 8 women on placebo, 4 using mifepristone plus ethinylestradiol, 2 using doxycycline, and 5 using mifepristone. There were no serious adverse events during the study. |

| Weisberg, 2009 | Two daily doses of 100 mg doxycycline during 5 days -- Two daily doses of 100 mg doxycycline + one daily dose of 20 ug ethinylestradiol during 5 days -- Two doses of 25 mg mifepristone for 1 day, then a daily oral dose of 20 ug ethinylestradiol for 4 days -- Two doses of 25 mg mifepristone for 1 day + two daily doses of 100 mg doxycycline for 5 days -- Two daily doses of placebo during 5 days | Two active treatment regimens were significantly more effective than the placebo in terminating a bleeding episode. Mifepristone plus ethinylestradiol and mifepristone plus doxycycline terminated a bleeding episode significantly more effectively within a mean of 4.0 (CI 3.5–4.6) and 4.4 (CI 3.8–5.2) days, respectively, compared with 6.4 (CI 4.8–8.6) for doxycycline plus ethinylestradiol, 6.4 (CI 4.4–9.2) for doxycycline alone, and 6.4 (CI 5.1–8.0) days for placebo (p < 0.0008 and 0.0108, respectively). Mifepristone combined with either ethinylestradiol or doxycycline was equally effective in stopping a bleeding episode. By 8 days after starting the first treatment, those who had stopped bleeding were: all women in the mifepristone and ethinylestradiol group; 97% in the mifepristone plus doxycycline group; 65.6% in the doxycycline group; 60% in the doxycycline plus ethinylestradiol group, and 70.3% in the placebo group. The percentage reductions in the mean number of bleeding and spotting days in the 90-day treatment phase when compared with pre-treatment were 17.7% for placebo, 22% for mifepristone plus ethinylestradiol, 25.7% for mifepristone plus doxycycline, and 5.5% for doxycycline alone, while there was an increase of 4.5% for doxycycline plus ethinylestradiol. | Satisfaction: Around 75% of women changed their perceptions on their bleeding patterns after the treatment, with no significant differences among groups (62% in the mifepristone plus ethinylestradiol group, 75% in the mifepristone plus doxycycline group, 70% in the doxycycline group, 82% in the doxycycline plus ethinylestradiol group, and 71% in the placebo group; p = 0.729). Before treatment, 85.3% of Implanon users felt their bleeding was “too long”; after treatment, 49.5% felt that the interval between bleeding episodes was “too short”. Adverse effects: There were no severe adverse events caused by the study drug. Women from all groups reported a wide range of minor secondary effects, with the most common being nausea and headaches. Nausea was present in 8 women with doxycycline, in 3 with doxycycline plus ethinylestradiol, in 6 with placebo, and in 5 with doxycycline plus mifepristone. Only one of them (in the placebo group) suspended the treatment due to nausea. Headaches were more common in women using doxycycline and ethinylestradiol; 9 women from this group reported them, in contrast to 2 in the placebo group, 4 in the doxycycline plus mifepristone group, and 3 in the doxycycline alone group. Less common secondary effects were vomit, diarrhoea, heartburn, stomach cramps or abdominal distension, vaginal discharge or itching, acne, extreme fatigue, and hot flashes. |

| Weisberg, 2009 | Group A received COCP (20 mcg ethinylestradiol/150 mcg desogestrel) for 42 consecutive days Group B received three daily doses of 500 mg mefenamic acid for two courses, 5 days each and 21 days apart -- No placebo | Comparing the efficacy between COCP and NSAID in treating the bleeding irregularities in etonogestrel implant users, the mean duration of bleeding days was 15.63 ± 2.55 for COCP, and 14.75 ± 2.33 for NSAID (p = 0.103). More women in the COCP group stopped bleeding in the 7 days after starting treatment than in the NSAID group (p < 0.05). After 42 days of treatment, a small number of women in both groups presented a recursive, unacceptable bleeding pattern after suspending treatment for 7 days or more. This was more frequent in the COCP group (p < 0.05). The mean duration of bleeding within the 90 days of treatment was 7.29 ± 3.16 for COCP, and 10.5 ± 4.14 for NSAID (p < 0.05). | Satisfaction: Not reported. Adverse effects: A wide range of minor side effects, the most common of which were nausea and headaches. |

| Edelman, 2020 | Two daily doses of 10 mg tamoxifen during 7 days -- Same for placebo | After the first treatment, women with tamoxifen experienced 9.8 (95% CI: 4.6–15.0) more consecutive days of amenorrhea than the placebo group. Those in the tamoxifen group also experienced more total days of no bleeding (amenorrhea or spotting) in the first 90 days [median: 73.5 (range 24–89) vs. 68 (range 11–81); p = 0.001]. They also had a longer time to restart bleeding or spotting after their first treatment as compared to the placebo group [Kaplan-Meier median: 12 days (range 1–56) vs. 6 days (range 1–38); p < 0.001]. There was a 1-day difference between groups in how fast bleeding stopped after the first treatment [median: 5 (range 1–21) vs. 6 (range 1–26); p = 0.029]. | Satisfaction: Women were satisfied with their implant during the whole study. Bleeding pattern satisfaction and acceptability was low and similar for both groups at the beginning of the study. Satisfaction was significantly higher in the tamoxifen group than in the placebo group after the initial treatment [median: 71 (range 8.5–100) vs. 31 (range 0–100); p < 0.001] and at the end of the first 90-day reference interval [median: 62 (range 16–100) vs. 46 (range 0–100); p = 0.023]. After completing the open-label phase, satisfaction with bleeding was not significantly different between the treatment groups [median: 67.5 (range 0–100) vs. 54.25 (range 0.5–9.8); p = 0.129]. Acceptability showed similar trends, with no significant differences between groups. Adverse effects: Few participants reported treatment-related adverse events, while no serious adverse events occurred during the study. More women taking tamoxifen reported fluid retention (12 vs. 1), headache (19 vs. 1), and mood changes (13 vs. 2). |

| Hou, 2016 | Monophasic oral contraceptive (30 mcg ethinylestradiol + 150 mg levonorgestrel) -- Placebo (28 capsules) | All 12 COC users and 75% of placebo users noted improvement in bleeding (p = 0.09). More women noted “significant” with COC use (n = 11 [92%]) than placebo (n = 5 [42%]) (p = 0.03). No woman in the COC group complained of worse bleeding, compared to two (17%) placebo users (p = 0.48). All 12 COC users and 75% of placebo users stopped bleeding during the first four weeks of treatment. COC users and placebo users who stopped bleeding did so after a median of 1 day (range 1–9) and 4.5 days (range 1–28), respectively (p = 0.63). All COC users and 9 placebo users returned for their 3-month follow-up visit. 12 out of 16 women who had used COCP for two months or more during the study saw better bleeding patterns, while 5 placebo users who kept their usealso saw improvements (p = 0.54). Surprisingly, 3 out of 15 women using COCP during the study did not report any improvement in their bleeding at the three-month point. 6 COCP users (38%) and 3 women under no treatment (60%) reported to still suffer from unscheduled bleeding, which is almost half of the patients (9 out of 21; p = 0.61). | Satisfaction: Women who expressed during registration their wish to have their implant removed were more likely to ask for removal in the following phases of the study (3/5 [60%] versus 1/17 (6%); p = 0.03). Adverse effects: Adverse effects seen in the first four weeks affecting more than one participant were headaches (n = 10), nausea or vomit (n = 3), cramps (n = 3), and breast tenderness (n = 4). There were no differences between groups for these events or for the average weight changes during the first four weeks. |

| Simmons, 2017 | Two daily doses of 10 mg tamoxifen during 7 days -- Same for placebo | Women in the tamoxifen group reported more days of baseline bleeding than the placebo group (p < 0.05, two-sample T test) and a slightly shorter duration of implant use (p > 0.05). Women using tamoxifen (10.5 ± 9.0) had less days with bleeding/spotting than placebo users (15.5 ± 8.5) in the 30 days after drug activation (with a median difference of 5 days, p = 0.05), with most of this difference being due to less days with bleeding (−9.9, −0.05). Days of bleeding: 5.0 ± 6.2 (tamoxifen users) vs. 8.6 ± 7.0 (placebo users (p = 0.006). Days of bleeding/spotting during the study (out of 180): 65.6 (tamoxifen users) vs. ± 37.5 (placebo users) 46.9 ± 28.1 Mean difference: 18.7 (−4.7, 42.1; p = 0.011). | Satisfaction: Satisfaction with the bleeding pattern was equivalent and low for both groups at baseline. Satisfaction data were available for 24 subjects in each group after the first course of the study drug, and for 22 tamoxifen and 21 placebo users at their final study visit. Although satisfaction increased in both groups after the first course of the study drug, it was significantly higher for tamoxifen users (mean VAS 70.3 mm for tamoxifen vs. 49.3 mm for placebo; p = 0.02). By 180 days, bleeding satisfaction was higher than baseline but equivalent for both groups (mean 61 ± 24.7 mm for tamoxifen vs. 53.6 ± 33.3 mm for placebo; p = 0.39). Adverse effects: Tamoxifen was well tolerated, with no serious adverse effects and side effects equivalent to placebo. |

| Zigler, 2018 | 15 mg ulipristal acetate during 7 days -- Same for placebo | At the end of the 30-days follow-up, the mean of days with bleeding was 12.0 (IQR 6–21) for the placebo group and 7.0 (IQR 4.5–11) for the ulipristal acetate group (p = 0.002). 3 women using placebo (9.7%) and 11 using ulipristal acetate (34.4%) stopped bleeding at day 10 (p = 0.03). | Satisfaction: Satisfaction with bleeding patterns was recorded at the start and at the end of the study. Both groups presented similar satisfaction levels at the beginning, while at the end, the ulipristal acetate users were more likely to be satisfied with their bleeding patterns than the placebo users (71.9% vs. 26.7%, respectively; p < 0.001). 27 women from the ulipristal acetate group declared to be “not happy at all” or “somewhat unhappy” with their bleeding. No patient declared their dissatisfaction levels. Most women from both groups stated they wanted their bleeding to be eliminated (63.3% from the ulipristal acetate group and 67.7% from the placebo group; p = 0.72). At the end of the study, more ulipristal acetate users wanted to keep their implant in comparison to placebo users (89.7% vs. 63.3%; p = 0.03). Adverse effects: There were few side effects reported during the treatment period, including headache (19.4% in placebo group, 9.4% in ulipristal acetate group), and nausea and vomiting (9.7% in placebo group, 3.1% in ulipristal acetate group). Groups were similar in side effects, with the majority experiencing no side effects (placebo group: 74.2%, ulipristal acetate group: 81.3%; p = 0.5). We did not encounter any serious adverse effects. All participants from both groups felt their medication was easy to use. All ulipristal acetate users stated they would use the medication again for bleeding, which was significantly different from placebo users (66.7%; p = 0.001). |

| Author/Year/ Country | Objective | Study Design/Duration/ Follow-Up | Initial Population/Dropout | General Characteristics of the Population (Age, Parity, BMI) | Progestin/Baseline Characteristics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Abdel Aleem, 2005 Egypt | To evaluate the possible role of tamoxifen (selective estrogen receptor modulators, SERM) in treating bleeding irregularities associated with Norplant contraceptive use. | Double-blinded randomized controlled trial Three months At 10 days, at the end of the first month, at the end of the second month, and at the end of the third month | 100 women Tamoxifen: 50 Placebo: 50 Dropout: 7% | Age: Tamoxifen: 32.48 ± 5.6/Placebo: 32.28 ± 6.1 Parity: Tamoxifen: 4.34 ± 1.7/Placebo: 4.70 ± 1.8 BMI: Tamoxifen: 24.79 ± 4.0/Placebo: 24.53 ± 3.3 | Norplant® Bleeding was defined as current episode of bleeding/spotting 8 days, or bleeding-free interval 15 days. Users were on their first year of Norplant®. |

| Nathirojanakun, 2006 Thailand | To evaluate the efficacy of valdecoxib and placebo for controlling irregular uterine bleeding in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) users. | Double-blind, placebo-controlled study 28 days Not reported | 51 women Valdecoxib: 25 Placebo: 26 Dropout: 9.8% | Age: Valdecoxib: 24.1 ± 6.59/Placebo: 25.1 ± 7.35 Parity: Valdecoxib: 1.2 ± 0.62/Placebo: 1.3 ± 0.54 BMI: Valdecoxib: 21.22 ± 3.13/Placebo: 21.06 ± 3.06 | DMPA Having 8 days or more of a bleeding or spotting prior to obvious bleeding. DMPA: For 12 meses |

| Phupong, 2006 Thailand | To evaluate the effects of tranexamic acid and placebo on controlling irregular uterine bleeding secondary to Norplant use. | Prospective randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 4 weeks 1 week post-treatment, and then at 4 weeks. | 68 women Tranexamic acid: 34 Placebo: 34 Dropout: 0% | Age: Tranexamic acid: 27.0 ± 5.7/Placebo: 29.1 ± 6.1 Parity: Tranexamic acid: 12 (35.3)/Placebo: 10 (29.4) Tranexamic acid: 18 (52.9)/Placebo: 16 (47.1) Tranexamic acid: 4 (11.8)/Placebo: 8 (23.5) BMI: Tranexamic acid: 22.7 ± 3.9/Placebo: 21.4 ± 3.0 | Norplant® Bleeding disturbances were defined as bleeding or spotting for eight or more continuous days or a current bleeding episode initiated after a bleeding-free interval of 14 days or less. Norplant inserted 3–36 months before enrollment. |

| Weisberg, 2006 Australia | To compare three treatments with placebo on the duration and recurrence of frequent and/or prolonged bleeding in Implanon users. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 180 days At 90 days | 179 women Mifepristone: 44 Doxycycline: 45 Mifepristone + ethinylestradiol: 45 Placebo: 45 Dropout: 6.1% | Age: Mifepristone: 29.9 ± 1.007/Placebo: 28.9 ± 0.995/Mifepristone + ethinylestradiol: 27.6 ± 0.995/Doxycycline: 28.8 ± 0.995 Parity: Only pregnancies are reported. BMI: Only weight (kilograms) is reported. | Implanon® Women who had used Implanon for contraception for ≥3 months and were experiencing prolonged or frequent bleeding patterns were recruited at four Australian sites either through clinics or by advertisement. They were enrolled into the treatment phase, provided they had met one of the WHO criteria for prolonged or frequent bleeding. |

| Archer, 2008 USA | To evaluate ethinylestradiol or ibuprofen compared to placebo on spotting and bleeding and a postcoital test in women using the levonorgestrel subcutaneous implant. | Multicenter prospective randomized study Once a month during one year or until the spotting and bleeding had stopped for 2 months. | 106 women Estrogen: 20 Ibuprofen: 42 Placebo: 44 Dropout: 0% | Age: not reported Parity: not reported BMI: Only weight | LNG subcutaneous implant Implant has more than 1 month, with spotting or bleeding lasting 8 or more consecutive days, or more than 10 out of 14 days in the previous 3 weeks, plus no treatment against spotting or bleeding in the last month. |

| Buasang, 2009 Thailand | To evaluate the efficacy of valdecoxib and placebo for controlling irregular uterine bleeding in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) users. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. 28 days At 4 weeks | 40 women Celecoxib: 20 Placebo: 20 Dropout: 0% | Age: Celecoxib: 34.10 ± 7.40/Placebo: 29.50 ± 9.84 Parity: Celecoxib: 2.20 ± 1.50/Placebo: 1.50 ± 0.51 BMI: Celecoxib: 21.90 ± 3.82/Placebo: 23.30 ± 2.45 | Jadelle® Current bleeding on the day of participation Users of Jadelle® for 9–13 months. |

| Weisberg, 2009 Australia | To compared four treatments against a placebo in Implanon users and tested whether repeated treatment improved subsequent bleeding patterns. | Randomized, double- blind, placebo-controlled trial. 90 days 90 days | 204 women Doxycycline Doxycycline + ethinylestradiol Mifepristone + ethinylestradiol Mifepristone + doxycycline Placebo: 40 Dropout: 13.9% | Age: Doxycycline: 28.6 ± 6.8/ Doxycycline + ethinylestradiol: 28.8 ± 6.0/ Placebo: 28.8 ± 5.8/ Mifepristone + ethinylestradiol: 29.1 ± 7.2/ Mifepristone + doxycycline: 29 ± 6.0/ Non-randomized: 28 ± 6.3 Weight: Doxycycline: 69.5 ± 14.3/ Doxycycline + ethinylestradiol: 69.3 ± 12.4/ Placebo: 71.5 ± 21.9/ Mifepristone + ethinylestradiol: 72.8 ± 26.2/ Mifepristone + doxycyline: 72.5 ± 17.5/ Non-randomized: 70.6 ± 19.0 | Implanon® Daily menstrual record for at least 90 days, then they could enroll in the treatment phase, as long as they met one of the WHO criteria for frequent bleeding/spotting (Belsey & Pinol, 1997), which is defined as a bleeding/spotting episode that lasts more than 10 days, or more than 4 bleeding/spotting episodes within 90 days. |

| Sethong, 2009 Thailand | To evaluate the efficacy of tranexamic acid and placebo for controlling irregular uterine bleeding in depot-medroxyprogesterone acetate (DMPA) users. | Prospective randomized trial double-blind, placebo-controlled study 28 days Not reported | 99 women Tranexamic acid: 50 Placebo: 49 Dropout: 1% | Age: Tranexamic acid: 29.6± 7.09/Placebo: 28.69 ± 7.671 Parity: Tranexamic acid: 1.32 ± 0.74/Placebo: 1.12 ± 0.60 BMI: Tranexamic acid: 23.11 ± 2.76/Placebo: 22.5 ± 2.07 | DMPA Being DMPA users for a period of 1–18 months; having 8 days or more with bleeding or spotting. |

| Dempsey, 2010 USA | To hypothesize that the estradiol vaginal ring will be acceptable to participants and will decrease bleeding during the first 3 months of DMPA use and increase continuation at 3 months. | Prospective, randomized, controlled, non-blinded trial 6 months 6 months | 71 women Vaginal ring: 35 Not intervened: 36 Placebo: no Dropout: At 3 months: DMPA: 36.1%, Vaginal ring: 25.7% At 6 months: DMPA: 56%, Vaginal ring: 51% | Age: 18–20 Total: 28 (39) DMPA: 14 (39), Ring: 14 (40) 21 or older Total: 43 (61) DMPA: 61 (22), Ring: 21 (60) Parity: None Total: 27 (38) DMPA: 11 (31), Ring: 16 (46) One Total: 29 (41) DMPA: 16 (44), Ring: 13 (47) Two or more Total: 15 (21) DMPA: 9 (25), Ring: 6 (17) BMI: ≤ 25 Total: 32 (58) DMPA: 20 (65), Ring: 12 (50) 25–29.9 Total: 16 (29) DMPA: 9 (29), Ring: 7 (29) ≥30 Total: 11 (13) DMPA: 2 (6), Ring: 5 (21) | DMPA Hadn’t used DMPA before, suffering from oligomenorrhea. |

| Warner, 2010 USA | The aim of the clinical trial reported here was to determine whether intermittent administration of SPRM CDB-2914 | Double-blind, randomized, controlled trial and placebo-controlled 6 months (all phases included) At 1, 3, and 6 months | 136 women CDB-2914: 69 Placebo: 67 Dropout: 14.7% | Age: CBD-2914: 36.9 (6.5)/Placebo: 35.8 (7.0) Parity: 0 CBD-2914: 14 (20)/Placebo: 20 (30) 1 CBD-2914: 18 (26)/Placebo: 13 (19) 2 CBD-2914: 30 (43)/Placebo: 27 (40) 3 CBD-2914: 6 (9)/Placebo: 7 (10) 4 CBD-2914: 1 (1)/Placebo: 0 (0) BMI: Not reported | LNG-IUS initiating use of an LNG-IUS for contraception, with regular menstrual cycles lasting 17–42 days, menstrual periods lasting less than 11 days. |

| Abdel Aleem, 2012 Egypt | To examine the effect of DOX compared with placebo in stopping a current bleeding episode during DMPA use as welL as the effect of drug treatment on the bleeding pattern in the 3 months following the treatment. | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial 3 months (including follow-up) At the 1st, 2nd, and 3rd months. | 68 women Doxycycline: 34 Placebo:34 Dropout: 14.7% | Age: Doxycycline: 29.6 ± 7.3 Placebo: 30.0 ± 5.7 Parity: The study only asks about living children. BMI: Not reported. | DMPA Users of DMPA as contraception for at least 1 month, complaining of a bleeding episode (defined as ≥8 bleeding or spotting days or bleeding-free interval of 15 days or less). The treatment package was started if the bleeding or spotting episode had lasted for the last 8 or more days in one continuum or when having bleeding or spotting occur within 15 days from the last bleeding episode. |

| Madden, 2012 USA | To evaluate whether oral naproxen or transdermal estradiol decreases bleeding and spotting in women initiating the levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system (LNG-IUS) Mirena® | Randomized controlled trial 16 weeks Calls at 4, 8, and 16 weeks + 1 visit at 12 weeks | 129 women Naproxen: 44 Transdermal estradiol: 42 Placebo: 43 Dropout: 17.8% | Age: <21: Estradiol: 5 (11.4%)/Naproxen: 5 (11.9%)/Placebo: 4 (9.3%) 21–29: Estradiol: 30 (68.2%)/Naproxen: 28 (66.7%)/Placebo: 30 (69.8%) ≥30: Estradiol: 9 (20. 5%)/Naproxen: 9 (21.4%)/Placebo: 9 (20.9%) Parity: 0: Estradiol: 20 (45.4%)/Naproxen: 22 (53.4%)/Placebo: 22 (51.1%) 1–2: Estradiol: 23 (52.3%)/Naproxen: 14 (33.3%)/Placebo: 18 (41.9%) ≥3: Estradiol: 1 (2.3%)/Naproxen: 6 (14.3%)/Placebo: 3 (7.0%) BMI: <25: Estradiol: 12 (27.3%)/Naproxen: 15 (35.7%)/Placebo: 22 (51.2%) 25–29.9: Estradiol: 10 (22.7%)/Naproxen: 15 (35.7%)/Placebo: 9 (20.9%) ≥30: Estradiol: 22(50.0%)/Naproxen: 12 (28.6%)/Placebo: 12 (27.9%) | Mirena® Not reported. |

| Sordal, 2013 Denmark, Ireland, Norway | To investigate whether counseling plus tranexamic acid or the NSAID, mefenamic acid, was superior to counseling plus placebo in the management of initial bleeding or spotting after levonorgestrel-releasing intrauterine system placement | Prospective, double-blind, three-arm, randomized placebo-controlled, phase IV 9 months (30 days for assessment) At 30 days | 187 women Tranexamic acid: 63 Mefenamic acid: 63 Placebo: 61 Dropout: 10.69% | Age: Tranexamic acid: 31.56 ± 7.2/Mefenamic acid: 32.96 ± 6.7/Placebo:33.16 ± 7.0 Parity: Tranexamic acid: 1.46 ± 1.1/Mefenamic acid: 1.76 ± 1.0 BMI: Tranexamic acid: 25.056 ± 4.54/Mefenamic acid: 24.766 ± 3.74/Placebo: 25.076 ± 4.63 | LNG-IUS Regular menstrual cycles (21–35 days). |

| Guiahi, 2015 USA | To understand whether using oral contraceptive pills (OCPs) results in temporary interruption of bleeding for etonogestrel contraceptive implant users during a 14-day course. | Double-blind, randomized controlled trial 14 days Weekly for a month, or until the first bleeding | 32 women OCPs: 16 Placebo: 16 Dropout: 1% | Age: OCPs: 22.46 ± 4.8/Placebo: 21.46± 3.0 Parity: Only pregnancies are reported. BMI: OCPs: 23.26 ± 2.9/Placebo: 23.36± 3.5 | Etonogestrel implant users who reported bothersome bleeding with a current bleeding–spotting episode of at least 7 consecutive days. |

| Hou, 2016 USA | Estimate symptom improvement rate of women with bleeding complaints using the etonogestrel contraceptive implant when started on continuous combined oral contraceptives. | Double-blind randomized, multicenter placebo-controlled trial 28 days Up to 3 months | 26 women COCs: 13 Placebo: 13 Dropout: 30.7% | Age: COCs: 25.4 ± 3.8/Placebo: 25.8 ± 5.0 Parity: 0: COCs: 8 (62%)/Placebo: 9 (69%) 1: COCs: 1 (8%)/Placebo: 3 (23%) 2: COCs: 2 (15%)/Placebo: 1 (8%) BMI: COCs: mean: 26.5, range: 18.9–38.9. Placebo: mean 23.1, range: 21.0–43.9. | Etonogestrel implants Significantly abnormal bleeding or heavy flow. |

| Simmons, 2017 USA | To evaluate whether a short course of tamoxifen reduces bleeding/spotting days compared to placebo in ENG implant users. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial 17 months 14 days after ending the treatment, then at 180 days or a last visit. | 56 women Tamoxifen: 28 Placebo: 28 Dropout: 39.2% | Age: Tamoxifen: 23.9 ± 5.7/Placebo: 25.4 ± 4.5 Parity (Nulliparous): Tamoxifen: 18 (64)/Placebo: 19 (68) BMI: Tamoxifen: 27.2 ± 7.3/Placebo: 28.4 ± 11.3 | Etonogestrel implant 15–45-years-old women using the ENG 68-mg subdermal implant) for at least 30 days. Frequent or prolonged bleeding or spotting during the past month. Frequent was defined as bleeding/spotting (B/S) more than every 24 days, and prolonged was defined as B/S every day in a row for 14 days or longer, consistent with prior study populations. |

| Cohen, 2019 USA | To determine if a course of oral tamoxifen following the placement of a levonorgestrel 52 mg intrauterine system (IUS) reduces bleeding/spotting days over 30 days | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical trial 16 months At 30 days | 37 women Tamoxifen: 18 Placebo: 19 Dropout: 8.1% for outcome 1 and 18.9% for outcome 2 | Age: Tamoxifen: 30.6 ± 7.6/Placebo: 28.8 ± 6.1 Parity (Nulliparous): Tamoxifen: 13 (76.5)/Placebo: 15 (88.2) BMI: Tamoxifen: 28.9 ± 8.0/Placebo: 23.7 ± 3.3 | LNG-IUS 15–45 years old women initiating levonorgestrel 52 mg IUS for contraception. |

| Zigler, 2019 USA | To evaluate if ulipristal acetate reduces the number of bleeding days in etonogestrel implant users in a 30-day period as compared to placebo. | Randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled trial. 8 months Participants received a weekly call, to fill out a follow-up survey, during 4 weeks. | 65 women Ulipristal acetate: 32 Placebo:33 Dropout: <10% | Age: Ulipristal acetate: 26.4 ± 6.2/Placebo: 25.5 ± 6.3 Parity: 0: Ulipristal acetate: 14 (43.7)/Placebo: 17 (54.8) 1: Ulipristal acetate: 5 (15.6)/Placebo: 7 (22.6) 2: Ulipristal acetate: 7 (21.9)/Placebo: 3 (9.7) +3: Ulipristal acetate: 6 (18.8)/Placebo: 4 (12.9) BMI: Ulipristal acetate: 29.6 ± 8.2/Placebo: 27.8 ± 7.0 | Etonogestrel subdermal implant (68 mg) 18–45 years old English-speaking women, with an implant for more than 90 days and less than 3 years before sign-up, as well as being unsatisfied with their bleeding pattern (more than 1 bleeding episode in the last 24 days). |

| Upawi, 2020 Malaysia | To evaluate whether unacceptable bleeding among the etonogestrel implant users could be better alleviated using combined oral contraceptive pills (COCP) or nonsteroidal anti-inflammation drug (NSAID). | Randomized controlled trial 18 months At 90 days | 86 women COCP: 43 Mefenamic acid: 43 Placebo: No Dropout: 2.3% | Age: COCP: 32 (29–35)/NSAID: 33 (30–35) Parity: 0: COCP: 0 (0)/NSAID: 1 (2.4) 1: COCP: 8 (19.05)/NSAID: 4 (9.5) 2: COCP: 16 (38.1)/NSAID: 16 (38.1) 3: COCP: 10 (23.8)/NSAID: 11 (26.2) 4: COCP: 5 (11.9)/NSAID: 8 (19.0) 5: COCP: 2 (4.8)/NSAID: 2 (4.8) 6: COCP: 1 (2.4)/NSAID: 0 (0) BMI: COCP: 26.55 ± 2.66 NSAID: 25.81 ± 3.31 | Implanon® Women with etonogestrel implants and abnormal menstrual cycles—defined as frequent or prolonged bleeding. Frequent bleeding was experiencing more than 4 bleeding/spotting episodes in a period of 90 days. Prolonged bleeding was having one or more bleeding/spotting episodes of more than 10 days in the same period. |

| Fava, 2020 Brazil | To assess the efficacy of ulipristal acetate (UPA) for reducing abnormal bleeding among women using the 52-mg levonorgestrel intrauterine system (LNG-IUS). | Double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study 30 days At 90 days | 30 women Ulipristal acetate: 15 Placebo: 15 Dropout: 16.6% | Age: 20–29: Ulipristal acetate: 4 (26.7%)/Placebo: 3 (30%) 30–39: Ulipristal acetate: 8 (53.3%)/Placebo: 4 (40.0%) ≥40: Ulipristal acetate: 3 (20.0%)/Placebo: 3 (30.0%) Parity: Nulliparous: Ulipristal acetate: 3 (20.0%)/Placebo: 3 (30%) ≥1: Ulipristal acetate: 12 (80.0%)/Placebo: 7 (70.0%) BMI: 20–24.9: Ulipristal acetate: 3 (21.4%)/Placebo: 4 (40.0%) 25–29.9: Ulipristal acetate: 7 (50.0%)/Placebo: 4 (40.0%) ≥30: Ulipristal acetate: 4 (28.6%)/Placebo: 2 (20.0%) | LNG-IUS Women aged 18–45 years who had been using the 52-mg LNG-IUS for at least 1 year but less than 4 years, reporting complaints of abnormal uterine bleeding that was prolonged (more than 14 days of bleeding) or frequent (less than 24 days between menstrual periods) in the previous month. |

| Edelman, 2020 USA | To evaluate whether a short course of tamoxifen decreases bothersome bleeding in etonogestrel contraceptive implant users. | Double-blind, randomized control trial 2 years and 3 months At 90 days | 112 women Tamoxifen: 57 Placebo: 55 Dropout after the first treatment: 7.1% Dropout at the sixth treatment: 73% | Age: Tamoxifen: 23.4 ± 4.5/Placebo: 24.5 ± 5.1 Parity: Only nulliparity is reported. BMI Tamoxifen: 27.4 ± 7.4/Placebo: 27.2 ± 7.5 | Etonogestrel implant Women aged 15–45 years using the etonogestrel 68-mg subdermal contraceptive implant for at least 30 days, who met criteria for frequent or prolonged bleeding or spotting during the previous month. Defined ‘frequent’ as two or more independent bleeding or spotting episodes, and ‘prolonged’, as seven or more consecutive days of bleeding or spotting in a 30-day interval. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Ceballos-Morales, A.; Villalobos-Lermanda, C.; González-Burboa, A.; Ciapponi, A.; Bardach, A. Treatment of Irregular Uterine Bleeding Caused by Progestin-Only Contraceptives: A Systematic Review. Sexes 2025, 6, 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030045

Ceballos-Morales A, Villalobos-Lermanda C, González-Burboa A, Ciapponi A, Bardach A. Treatment of Irregular Uterine Bleeding Caused by Progestin-Only Contraceptives: A Systematic Review. Sexes. 2025; 6(3):45. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030045

Chicago/Turabian StyleCeballos-Morales, Alejandra, Celeste Villalobos-Lermanda, Alexis González-Burboa, Agustín Ciapponi, and Ariel Bardach. 2025. "Treatment of Irregular Uterine Bleeding Caused by Progestin-Only Contraceptives: A Systematic Review" Sexes 6, no. 3: 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030045

APA StyleCeballos-Morales, A., Villalobos-Lermanda, C., González-Burboa, A., Ciapponi, A., & Bardach, A. (2025). Treatment of Irregular Uterine Bleeding Caused by Progestin-Only Contraceptives: A Systematic Review. Sexes, 6(3), 45. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6030045