Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Reduce Risk Sexual Behaviours Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Elegibility Criteria

2.2. Information Sources and Search Strategy

2.3. Selection Process

2.4. Data Items and Extraction

2.5. Quality Assessment

3. Results

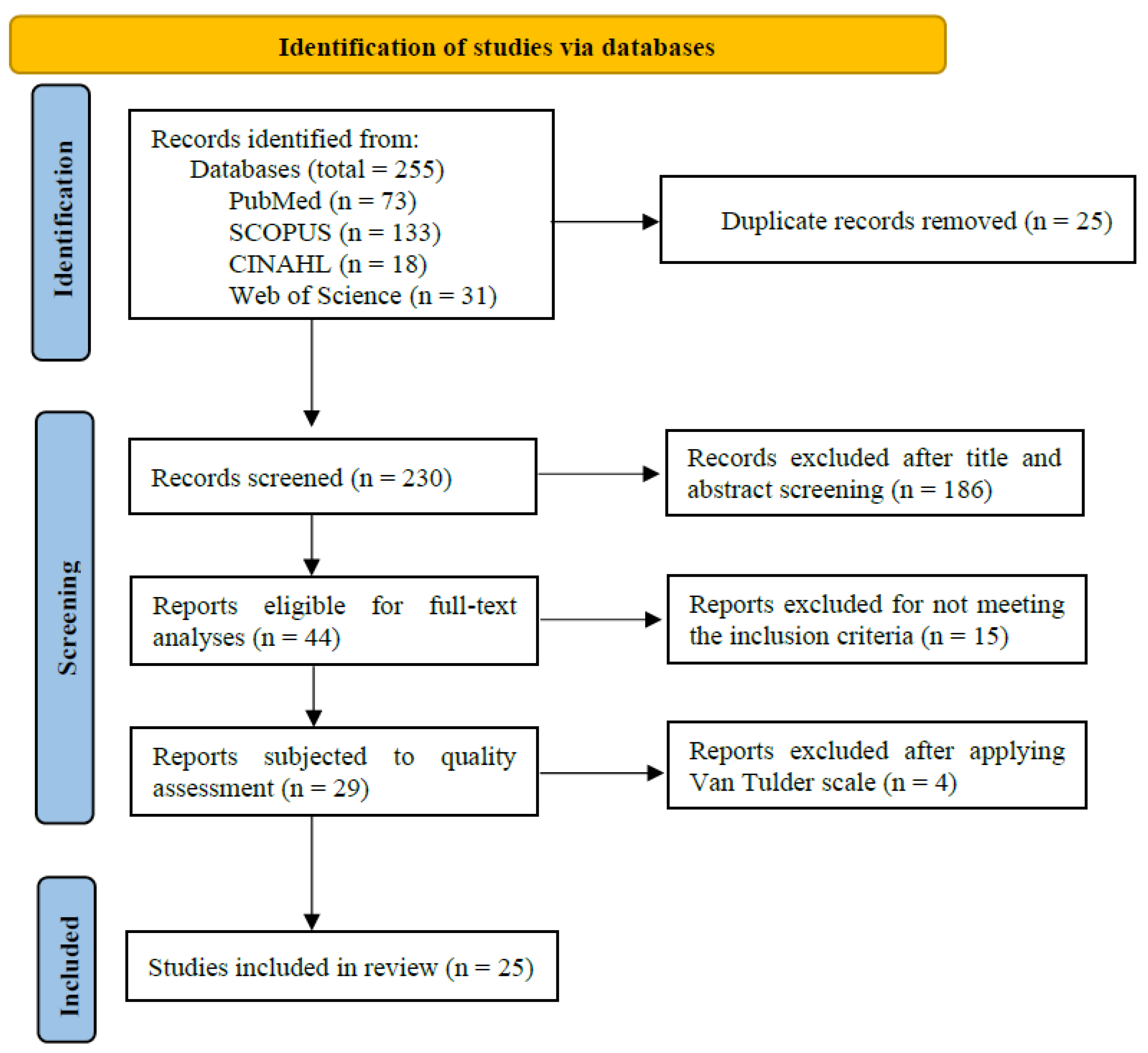

3.1. Study Selection

3.2. Characteristics of the Sample

3.3. Study Results

3.3.1. Sexual Risk Behaviours

3.3.2. Comprehensive Sexuality Education Interventions

3.3.3. Effectiveness of the Interventions

4. Discussion

Limitations

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Scope Note: Sexual Education. Health Sciences Descriptors. 2017. Available online: https://decs.bvsalud.org/en/ths/resource/?id=13116&filter=ths_termall&q=educacion%20sexual (accessed on 4 April 2023).

- Standards for Sexuality Education in Europe. A Framework for Policy Makers, Educational and Health Authorities and Specialist. WHO. 2010. Available online: https://www.icmec.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/06/WHOStandards-for-Sexuality-Ed-in-Europe.pdf (accessed on 17 December 2024).

- Garzón-Orjuela, N.; Samacá-Samacá, D.; Moreno-Chaparro, J.; Ballesteros-Cabrera, M.P.; Eslava-Schmalbach, J. Effectiveness of Sex Education Interventions in Adolescents: An overview. Compr. Child Adolesc. Nurs. 2021, 44, 15–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estudio Mundial Concluye que la Educación Sexual de Amplio Espectro es Esencial para la Igualdad de Género y la Salud Reproductiva. UNESCO. 2023. Available online: https://www.unesco.org/es/articles/estudio-mundial-concluye-que-la-educacion-sexual-de-amplio-espectro-es-esencial-para-la-igualdad-de (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Barbero-Radío, A.M.; De Diego-Cordero, R.; García-Carpintero, M.Á.; Tarriño-Concejero, L. Creencias, Actitudes y Motivaciones de la Violencia en las Relaciones de Noviazgo en Jóvenes y Adolescentes. Guía para Docentes, 2022nd ed.; Editorial Universidad de Sevilla: Seville, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Güemes-Hidalgo, M.; Ceñal, M.J.; Hidalgo, M.I. Desarrollo durante la adolescencia. Aspectos físicos, psicológicos y sociales. Rev. Pediatr. Integral 2017, XXI, 233–244. [Google Scholar]

- WHO Recommendations on Adolescent Sexual and Reproductive Health and Rights. WHO. 2018. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241514606 (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Cabrera-Fajardo, D.P. Educación Sexual Integral en la escuela. Rev. UNIMAR 2022, 40, 136–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Velasco-Gijón, I.M.; Polo-Oliver, A.; Gutiérrez-Ramírez, L.; Arias-Arias, A.; Tejera-Muñoz, A. Encuesta para conocer la percepción sobre la educación sexual en adolescentes. Rev. Esp. Salud Pública 2024, 98, e202402005. [Google Scholar]

- González-Cano, M.; Garrido-Peña, F.; Gil-Garrcía, E.; Lima-Serrano, M.; Cano-Caballero, M.D. Sexual behaviour, human papillomavirus and its vaccine: A qualitative study of adolescents and parents in Andalusia. BMC Public Health 2021, 21, 1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- (Des)Información Sexual: Pornografía y Adolescencia. Save the Children España. 2020. Available online: https://www.savethechildren.es/informe-desinformacion-sexual-pornografia-y-adolescencia (accessed on 10 April 2023).

- Lima-Serrano, M.; Lima-Rodríguez, J.S. Efecto de la estrategia de promoción de salud escolar Forma Joven. Gac. Sanit. 2019, 33, 74–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Clavo, P. Infecciones de transmisión sexual en adolescentes. ¿Cuándo está indicado hacer un cribado? Rev. Form. Contin. Soc. Esp. Med. Adolesc. (Adolescere) 2022, X, 28–36. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández, E.K. Educación Sexual y Conductas Sexuales de Riesgo en Institución Educativa de Nuñumabamba. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias de la Salud y Escuela Académico Profesional de Obstetricia, Universidad Nacional de Cajamarca, Cajamarca, Peru, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lameiras, M.; Rodríguez, Y.; Ojea, M.; Dopereiro, M. Programa Coeducativo de Desarrollo Psicoafectivo Y Sexual, 1st ed.; Colección Ojos Solares Pirámides: San Vicente del Raspeig, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Sanz-Lorente, M. Las enfermedades de transmisión sexual en el siglo XXI. Hosp. Domic. 2023, 7, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moreno, A.; Cubero, C.; Belloc, L.; Minguillón, N.; Casaus, M.A. Infecciones de Transmisión Sexual en Adolescentes: Revisión Bibliográfica. 2021. Available online: https://revistasanitariadeinvestigacion.com/infecciones-de-transmision-sexual-en-adolescentes-revision-bibliografica/ (accessed on 9 April 2023).

- Cochrane Handbook for Systematic Reviews of Interventions. The Cochrane Collaboration. 2011. Available online: https://training.cochrane.org/handbook (accessed on 2 May 2023).

- Page, M.J.; McKenzie, J.E.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. Declaración PRISMA 2020: Una guía actualizada para la publicación de revisiones sistemáticas. Rev. Esp. Cardiol. 2021, 74, 790–799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jo, J.K.; Autorino, R.; Chung, J.H.; Kim, K.S.; Lee, J.W.; Baek, E.J.; Lee, S.W. Randomized Controlled Trials in Endourology: A Quality Assessment. J. Endourol. 2013, 27, 1055–1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, S.W. Meta-analysis and Quality Assessment of Randomized Controlled Trials. Hanyang University College of Medicine. Hanyang Med. Rev. 2015, 35, 33–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernández-Sampieri, R.; Fernández-Collado, C.; Baptista-Lucio, P. Metodología de la Investigación, 6th ed.; McGraw-Hill: Mexico City, Mexico, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Perestelo-Pérez, L. Standards on how to develop and report systematic reviews in Psychology and Health. Int. J. Clin. Health Psychol. 2013, 13, 49–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Pino, C.; Frías, O.; Palomino, M. La revisión sistemática cuantitativa en enfermería. Rev. Iberoam. Enferm. Comunitaria 2014, 7, 24–40. [Google Scholar]

- Barbee, A.P.; Cunningham, M.R.; Antle, B.F.; Langley, C.N. Impact of a relationship-based intervention, Love Notes, on teen pregnancy prevention. Fam. Relat. 2022, 72, 2569–2588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barbee, A.P.; Cunningham, M.R.; Zyl, M.; Antle, B.F.; Langley, C.N. Impact of two adolescent pregnancy prevention interventions on risky sexual behavior: A three-arm cluster randomized control trial. Am. J. Public Health 2016, 106, 85–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Espada, J.P.; Morales, A.; Orgilés, M.; Jemmott, J.B.; Jemmott, L.S. Short-Term evaluation of a skill-development sexual education program for Spanish adolescents compared with a well-established program. J. Adolesc. Health 2015, 56, 30–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gómez-Lugo, M.; Morales, A.; Saavdra-Roa, A.; Niebles-Charris, J.; Abello-Luque, D.; Marchal-Bertrans, L.; García-Roncallo, P.; García-Montaño, E.; Pérez-Pedraza, D.; Espada, J.P.; et al. Effects of sexual risk-reduction intervention for teenagers: A cluster-randomized control trial. AIDS Behav. 2022, 26, 2446–2458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hegdahl, H.K.; Musonda, P.; Svanemyr, J.; Zulu, J.M.; Gronvik, T.; Jacobs, C.; Sandoy, I.F. Effects of economic support, comprehensive sexuality education and community dialogue on sexual behaviour: Findings from a cluster-RCT among adolescent girls in rural Zambia. Soc. Sci. Med. 2022, 306, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, Z.; Fu, Y.; Wang, X.; Guo, F.; Hee, J.; Epi, M.C. Tang, K. Effects of sexuality education on sexual knowledge, sexual attitudes, and sexual behaviors of youths in China: A cluster-randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2023, 72, 607–615. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jerlström, C.; Adolfsson, A. Prevention of chlamydia infections with theater in school sex education. J. Sch. Nurs. 2020, 36, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lohan, M.; Brennan-Wilson, A.; Hunter, R.; Gabrio, A.; McDais, L.; Young, H.; French, R.; Aventin, A.; Clarke, M.; McDowell, C.; et al. Effects of gender-transformative relationships and sexuality education to reduce adolescent pregnancy (The JACK trial): A cluster-randomised trial. Lancet Public Health 2022, 7, 626–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mbizo, M.T.; Kasonda, K.; Muntalima, N.C.; Rosen, J.G.; Inambwae, S.; Namukonda, E.S.; Mungoni, R.; Okpara, N.; Phiri, C.; Chelwa, N.; et al. Comprehensive sexuality education linked to sexual and reproductive health services reduces early and unintended pregnancies among in-school adolescent girls in Zambia. BMC Public Health 2023, 23, 348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millanzi, W.C.; Kibusi, S.M.; Osaki, K.M. Effect of integrated reproductive health lesson materials in a problem-based pedagogy on soft skills for safe sexual behaviour among adolescents: A school-based randomized controlled trial in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2022, 17, e0263431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Millanzi, W.C.; Kibusi, S.M.; Osaki, K.M. The effect of educational intervention on shaping safe sexual behavior based on problem-based pedagogy in the field of sex education and reproductive health: Clinical trial among adolescents in Tanzania. Health Psychol. Behav. Med. 2022, 10, 262–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, A.; Orgilés, M.; Espada, J.P. Sexually unexperienced adolescents benefit the most from a sexual education program for adolescents: A longitudinal cluster randomized controlled study. AIDS Educ. Prev. 2020, 32, 493–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morrison-Beedy, D.; Jones, S.H.; Xia, Y.; Tu, X.; Crean, H.F.; Carey, M.P. Reducing sexual risk behavior in adolescent girls: Results from a randomized controlled trial. J. Adolesc. Health 2013, 52, 314–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, R.F.; Vesely, S.K.; Green, J.; Clements-Nolle, K.; Lu, M. Adolescent pregnancy prevention among youths living in group care homes: A cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 38–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oman, R.F.; Vesely, S.K.; Green, J.; Fluhr, J.; Williams, J. Short-Term impact of a teen pregnancy-prevention intervention implemented in group homes. J. Adolesc. Health 2016, 59, 584–591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Philliber, A. The IN clued program: A randomized control trial of an effective sex education program for lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer, and questioning youths. J. Adolesc. Health 2021, 69, 636–643. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tingey, L.; Chambers, R.; Rosenstock, S.; Lee, A.; Goklish, N.; Larzelere, F. The impact of a sexual reproductive health intervention for American Indian adolescents on predictors of condom use intention. J. Adolesc. Health 2017, 60, 284–291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Widman, L.; Golin, C.E.; Kamke, K.; Burnette, J.L.; Prinstein, M.J. Sexual assertiveness skills and sexual decision-making in adolescent girls: Randomized controlled trial of an online program. Am. J. Public Health 2018, 108, 96–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ybarra, M.; Goodenow, C.; Rosario, M.; Saewyc, E.; Prescott, T. An mhealth intervention for pregnancy prevention for LGB teens: An RCT. Am. Acad. Pediatr. 2021, 147, e2020013607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yakubu, I.; Garmaroudi, G.; Sadeghi, R.; Tol, A.; Yekaninejad, M.S. Yidana, A. Assesing the impact of an educational intervention program on sexual abstinence based on the health belief model amongst adolescent girls in Northem Ghana, a cluster randomized control trial. Reprod. Health 2019, 16, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manaseri, H.; Roberts, K.D.; Barker, L.T.; Ma, T.T. Pono Choices: Lessons for school leaders from the evaluation of a teen pregnancy prevention program. J. Sch. Health 2019, 89, 246–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mathews, C.; Eggers, S.M.; Townsend, L.; Aaro, L.E.; De Vries, P.J.; Mason-Jones, A.J.; De Koker, P.; McClinton, T.; Mtshizana, Y.; Koech, J.; et al. Effects of PREPARE, a multi-component, school-based HIV and intimate partner violence (IPV) prevention programme on adolescent sexual risk behaviour and IPV: Cluster randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2016, 20, 1821–1840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tingey, L.; Chambers, R.; Patel, H.; Littlepage, S.; Lee, S.; Lee, A.; Susan, D.; Melgar, L.; Slimp, A.; Rosenstock, S. Prevention of sexually transmitted diseases and pregnancy prevention among native American youths: A randomized controlled trial, 2016–2018. Am. J. Public Health 2021, 111, 1874–1884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wong, M.L.; Ng, J.Y.S.; Chan, R.K.W.; Chio, M.T.W.; Lim, R.B.T.; Koh, D. Randomized controlled trial of abstinence and safer sex intervention for adolescents in Singapore: 6-month follow-up. Health Educ. Res. 2017, 32, 233–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Manlove, J.; Welti, K.; Whitfield, B.; Faccio, B.; Finocharo, J.; Ciaravino, S. Impacts of Re:MIX-A school-based teen pregnancy prevention program incorporating young parent coeducators. J. Sch. Health 2021, 91, 915–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, R.; Zhang, L.; Fu, X.X. Sexual and reproductive health related knowledge, attitude and behaviour among senior high school and college students in 11 provinces and municipalities of China. Chin. J. Public Health 2019, 35, 1330–1338. [Google Scholar]

- Abril, E.; Román, R.; Cubillas, M.J.; Domínguez, S.E. Creencias sobre el uso del condón en una población universitaria. Cienc. Ergo Sum 2018, 25, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolaños, M.R. Barreras para el acceso y el uso del condón desde la perspectiva de género. Horiz. Sanit. 2019, 18, 67–74. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes-Da Fonte, V.R.; D´Onofrio, C.; De Souza, N.; Amorim, C.M.; Ribeiro, M.T.; Spindola, T. Factores asociados con el uso del preservativo entre hombres jóvenes que tienen sexo con hombres. Enferm. Glob. 2017, 46, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, R.; Martínez, J.L. Factores asociados al debut sexual, actividad sexual en línea y calificación en estudiantes de Morelia. Rev. Salud Pública Nutr. 2018, 17, 16–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pérez, Y.C.; Apupalo, M.M.; Creagh, I. Funcionamiento familiar y conducta sexual de riesgo en adolescentes de la comunidad de Yanayacu, 2015–2016. Rev. Habanera Cienc. Méd. 2018, 17, 789–799. [Google Scholar]

- Simon, D.J.; Paul, B.; Kiragu, A.; Olorunsaiye, C.Z.; Joseph, F.; Joseph, G.; N´Gou, M.D. Prevalence and factors associated with condom use among sexually active young women in Haiti: Evidence from the 2016/2017 Haiti demographic and health survey. BMC Women’s Health 2023, 146, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alpízar, J.; Rodríguez, P.; Cañete, R. Intervención educativa sobre educación sexual en adolescentes de una escuela secundaria básica. Unión de Reyes, Matanzas, Cuba. Rev. Méd. Electrón. 2014, 36, 572–582. [Google Scholar]

- Dair, R.; Canino, J.A.; Cruz, M.; Barbé, A.; García, M. Infecciones de transmisión sexual: Intervención educativa en adolescentes de una escuela de enseñanza técnica profesional. Medwave 2014, 14, e5891. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Orrego, J.M.; Paino, M.; Fonseca-Pedrero, E. Programa educativo ‘Trampolín’ para adolescentes con problemas graves del comportamiento: Perfil de sus participantes y efecto de la intervención. Aula Abierta 2016, 44, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avellana, T.; Morlans, P.; Artal, M.P.; García, M.T.; Hernando, N.; López, P. Intervención Educativa Enfermera con el Propósito de Mejorar el Conocimiento y Reducir la Incidencia de ETS en Adolescentes. 2023. Available online: https://revistasanitariadeinvestigacion.com/intervencion-educativa-enfermera-con-el-proposito-de-mejorar-el-conocimiento-y-reducir-la-incidencia-de-ets-en-adolescentes/#google_vignette (accessed on 7 April 2023).

- Gómez, R.T.; Machado, D.L.; Solaya, L.Y.; Blanco, N. Intervención educativa dirigida a uso de anticonceptivos en adolescentes. Rev. Eugenio Espejo 2023, 17, 53–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- López, L.M.; Bernholc, A.; Chen, M.; Tolley, E.E. School-based interventions for improving contraceptive use in adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2016, 6, CD012249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, M.J.; Jaramillo, J.P. Efectividad de un programa educativo en mujeres adolescentes con gingivitis. Medisan 2017, 21, 879–886. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez, V.; Aguilar, A.; González, F.; Esquius, L.; Varqué, C. Evolución de los conocimientos sobre alimentación: Una intervención educativa en estudiantes universitarios. Rev. Chil. Nutr. 2017, 44, 19–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cerrón, A.S.; Vega, E.O. Efectividad de una intervención educativa en redes sociales sobre los conocimientos y actitudes en sexualidad de adolescentes de una institución educativa (Lima, Perú). Matronas Prof. 2021, 22, 40–46. [Google Scholar]

- Antón, A.I. Educación sexual saludable en adolescentes. Nuberos Cient. 2017, 3, 69–73. [Google Scholar]

- Villa-Rueda, A.A.; Landeros, E.A.; Shokoohi, M.; Ramírez, N.; Benavides, R. “Usando condón”: A theory-based quasi-experimental intervention to improve perceived self-efficacy for condom use among Mexican adolescent. Health Addit./Salud Drog. 2022, 22, 214–225. [Google Scholar]

- Gómez-Inclán, S.; Durán-Arenas, L. El acceso a métodos anticonceptivos en adolescentes de la Ciudad de México. Salud Pública Méx. 2017, 59, 236–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dzib, D.L.B.; Hernández, R.C.; Dzib, S.P. La educación sexual y su importancia en su difusión para disminuir el embarazo en las estudiantes de la división académica de educación y artes de la Universidad Juárez autónoma de Tabasco. Perspect. Docentes 2015, 59, 19–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ariel, E.; Reyes, G. Infecciones de transmisión sexual. Un problema de salud pública en el mundo y en Venezuela. Comunidad Salud 2016, 14, 63–71. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez-Conde, M.; Vivancos, M.J.; Moreno-Guillén, S. Profilaxis preexposición (PrEP) frente al VIH: Eficacia, seguridad e incertidumbres. Farm. Hosp. 2017, 41, 630–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendoza, L.A.; Claros, D.I.; Peñaranda, C.B. Actividad sexual temprana y embarazo en la adolescencia: Estado del arte. Rev. Chil. Obs. Ginecol. 2016, 81, 243–253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reyna, V.F.; Mills, B.A. Theoretically motivated interventions for reducing sexual risk taking in adolescence: A randomized controlled experiment applying fuzzy-trace theory. J. Exp. Psychol. Gen. 2014, 143, 1627–1648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wagman, J.A.; Gray, R.H.; Campbell, J.C.; Thoma, M.; Ndyanabo, A.; Ssekasanvu, J.; Nalugoda, F.; Kagaayi, J.; Nakigozi, G.; Serwadda, D.; et al. Effectiveness of an integrated intimate partner violence and HIV prevention intervention in Rakai, Uganda: Analysis of an intervention in a cluster randomized cohort. Lancet Glob. Health 2015, 3, 23–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dinaj-Koci, V.; MA, L.D.; Wang, B.; Lunn, S.; Marshall, S.; Li, X.; Stanton, B. Adolescent sexual health education: Parents benefit too. Health Educ. Behav. 2015, 42, 648–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Items | Answers and Scores | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Yes | No | Don’t Know | |

| A. Was the randomization method appropriate? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| B. Was the treatment allocation concealed? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| C. Were the groups similar at baseline regarding the most important prognostic indicators? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| D. Were the patients blinded to the intervention? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| E. Was the care provider blinded to the intervention? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| F. Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all group similar? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| G. Were co-interventions avoided or similar? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| H. Was the compliance acceptable in all groups? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| I. Was the drop-out rate described and acceptable? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| J. Was the timing of the outcome assessment in all group similar? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| K. Did the analysis include an intention-to-treat analysis? | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Authors | Period/Location | Sample (Ages, Genders) |

|---|---|---|

| Barbee et al. [25] | The study period encompassed 31 months, from the end of 2011 to 2014, collecting follow-up data until 2015. Extracurricular activities were carried out in a camp organized by 23 youth service organizations. USA. | 1448 adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15.72; 63% were women, and 37% were men. IG-RR: 515. IG-LN: 511. CG-PW: 422. |

| Barbee et al. [26] | The study period was between September 2011 and March 2014. Extracurricular activities were carried out in a camp organized by 23 youth service organizations. USA. | 1208 adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15.72; 63% were women, and 37% were men. IG-RR: 431; 63.6% women and 36.4% men, with a mean age of 15.77 years old. IG-LN: 412; 64.32% women and 35.68% men, with a mean age of 15.69 years old. CG-PW: 365; 62.27% women and 37.73% men, with a mean age of 15.71 years old. |

| Espada et al. [27] | The study period corresponded to 2012, in 18 high schools and during class hours. Spain. | 1563 adolescents aged between 14 and 16 years old, with a mean of 14; 51.1% were men, and 48.9% were women. IG-C1 (IG-COMPAS): 622; 51.8% were men, and 48.2% were women. IG-C2 (IG-Cuídate): 442; 55.4% were men, and 44.6% were women. CG: 499; 46.3% were men, and 53.7% were women. |

| Gómez-Lugo et al. [28] | Study period not specified. Colombia. | 2047 adolescents aged between 14 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15.24; 52.1% were women, and 47.9% were men. IG 891 (8 schools): 55.25% women and 44.75% men. CG 1156 (6 schools): 49.8% women and 50.2% men. |

| Hegdahl et al. [29] | The study period was from July 2016 to 2018, with a two-year follow-up period from 2018 to 2020, in 157 7th-grade schools. Zambia. | 4922 female adolescents, with a mean age of 14.1 years old. |

| Hu et al. [30] | The study period was between October 2018 and December 2019 in 29 high schools from Yunnan and Guangdong. China. | 3151 male and female adolescents. IG: A total of 1760 students with a mean age of 16.13 years old; 47.44% were women, and 52.56% were men. IG: A total of 1391 subjects with a mean age of 16.04 years old; 44.93% were women, and 55.07% were men. |

| Jerlström and Adolfsson [31] | The study period was between December 2019 and March 2017, in 8th-grade schools. Sweden. | 963 adolescents aged 15 years old; 49.52% were women, and 49.88% were men. IG: 497; 50% were women, and 50% were men. CG: 466; 49% were women, and 50% were men. |

| Lohan et al. [32] | The study period was from 1 February 2018 to 6 March 2020, in 62 schools. United Kingdom. | 6556 adolescents aged 14–15 years old. IG: 4100; 51.70% were women, and 29.48% were men. CG: 4116; 45.48% were women, and 51.53% were men. |

| Mbizo et al. [33] | The study period was between August 2017 and December 2020, in high schools and health facilities from the Solwezy and Mufumbwe districts. Zambia. | 986 female adolescents; 54.8% were aged 15–19 years old (with a mean of 15 in a range from 12 to 24). IG-1: A total of 245 students. IG-2: A total of 354 students. CG-2: A total of 287 students. |

| Millanzi, Kibusi, and Osaki [34] | The study period was between September 2019 and September 2020, in 12 high schools. Tanzania. | 660 adolescents aged between 12 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15; 57.5% were women, and 42.5% were men. |

| Millanzi, Kibusi, and Osaki [35] | The study period was between September 2019 and September 2020, in 12 high schools. Tanzania. | 660 adolescents aged between 12 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15; 57.5% were women, and 42.5% were men. |

| Morales et al. [36] | Study period not specified. Spain. | 699 adolescents aged between 14 and 16 years old, with a mean of 14.66; 53.6% were women. IG: 379; 31.7% women and 48.3% men, with a mean age of 14.63 years old. CG: 320; 55.9% women and 44.1% men, with a mean age of 14.71 years old. |

| Morrison-Beedy et al. [37] | Study period not specified. USA. | 639 women adolescents aged between 15 and 19 years old, with a mean of 16.5. IG: 329. CG: 310. |

| Oman et al. [38] | The study period was from 2012 to 2014, in 14 group homes. USA. | 1036 adolescents included in the system living in group care homes and aged 13–18 years old, with a mean of 16.1 considering both groups; 79% were men, and 21% were women. IG: 517; 78.9% were men, and 21.1% were women. CG: 519; 78.4% were men, and 21.6% were women. |

| Oman et al. [39] | The study period was from 2012 to 2014, in 14 group homes. USA. | 1037 adolescents included in the system living in group care homes and aged 13–18 years old, with a mean of 16.2 considering both groups; 82% were men, and 18% were women. IG: 517; 81.5% were men, and 18.6% were women. CG: 519; 77.9% were men, and 22.1% were women. |

| Philliber et al. [40] | The study period was between February 2019 and March 2020. USA. | 1401 LGBTQ adolescents and young individuals aged between 14 and 22 years old, with a mean of 16. |

| Tingey et al. [41] | The study period corresponded to the summers of 2011 and 2012, in 2 basketball camps for 8 days. USA. | 267 adolescents aged between 13 and 19 years old, with a mean of 15.1; 56% were women, and 44% were men. |

| Widman et al. [42] | The study period was during autumn 2015, in 4 high schools. USA. | 222 female adolescents aged between 12 and 16 years old, with a mean of 15.2. IG: 107/CG: 115. |

| Ybarra et al. [43] | The study period was from 24 January 2017, to 12 January 2018, with enrolment by telephone. USA. | 948 cisgender girls aged between 14 and 19 years old, with a mean of 16.1. IG: 473, with a mean age of 16.14 years old. CG: 475, with a mean age of 15.97 years old. |

| Yakubu et al. [44] | The study period was between April and August 2018, in 6 high schools. Ghana. | 363 single female adolescents aged 13–19 years old. IG: 183; 22.8% were aged 14–16 years old, and 77.2% were between 17 and 19 years old. CG: 180; 16.9% were aged 14–16 years old, and 83.1% were between 17 and 19 years old. |

| Manaseri et al. [45] | The study period was between autumn 2011 and spring 2013, in 34 schools. Hawaii. | 1783 adolescents aged between 11 and 13 years old, with a mean of 12; 52% were women, and 48% were men. IG: 1158. CG: 625. |

| Mathews et al. [46] | The study period was between February and March 2013, in 8th-grade high schools. South Africa. | 3451 adolescents with a mean age of 13 years old. IG: 1748; 37.9% were men, and 62.1% were women. The mean age was 13.7 years old. CG: 1703; 41.5% were men, and 58.5% were women. The mean age was 13.71 years old. |

| Tingey et al. [47] | The study period was between 2016 and 2018, in a summer camp. USA. | 534 adolescents aged between 11 and 19 years old, with a mean of 13.27. |

| Wong et al. [48] | The study period was between November 2009 and October 2014. Singapore. | 688 heterosexual adolescents aged between 16 and 19 years old, with a mean of 18. IG: 337; 44.51% were men, and 55.49% were women. CG: 351; 43.3% were men, and 56.7% were women. |

| Manlove et al. [49] | The study period was between autumn 2019 and autumn 2018, in 57 classrooms from 3 schools. Texas. | 621 adolescents aged 13–17 years old. IG: 347; 33.2% women and 46.8% men, with a mean age of 13.85 years old. CG: 279; 49.4% women and 50.6% men, with a mean age of 13.86 years old. |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rodríguez-García, A.; Botello-Hermosa, A.; Borrallo-Riego, Á.; Guerra-Martín, M.D. Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Reduce Risk Sexual Behaviours Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sexes 2025, 6, 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010006

Rodríguez-García A, Botello-Hermosa A, Borrallo-Riego Á, Guerra-Martín MD. Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Reduce Risk Sexual Behaviours Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sexes. 2025; 6(1):6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleRodríguez-García, Ana, Alicia Botello-Hermosa, Álvaro Borrallo-Riego, and María Dolores Guerra-Martín. 2025. "Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Reduce Risk Sexual Behaviours Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review" Sexes 6, no. 1: 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010006

APA StyleRodríguez-García, A., Botello-Hermosa, A., Borrallo-Riego, Á., & Guerra-Martín, M. D. (2025). Effectiveness of Comprehensive Sexuality Education to Reduce Risk Sexual Behaviours Among Adolescents: A Systematic Review. Sexes, 6(1), 6. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes6010006