Explaining Gender Neutrality in Capital Punishment Research by Way of a Systematic Review of Studies Citing the ‘Espy File’

Abstract

1. Introduction

Objective and Research Questions

- To what extent, and for what purpose, are Espy file data used in academic research?

- How prevalent and what approach is taken for those studies identified as “gendered”, “raced”, or otherwise utilized intersectional frameworks?

- Are there differences among men and women scholars in research focus and methodology?

- How is the Espy file accessed and to whom is it attributed and/or supplemented with other data sources? Are weaknesses acknowledged and/or addressed?

2. Background

2.1. The Espy File

2.2. It’s a “Guy Thing”

2.3. Credit-Giving without Giving Credit Where It Is Due

3. Data and Methodology

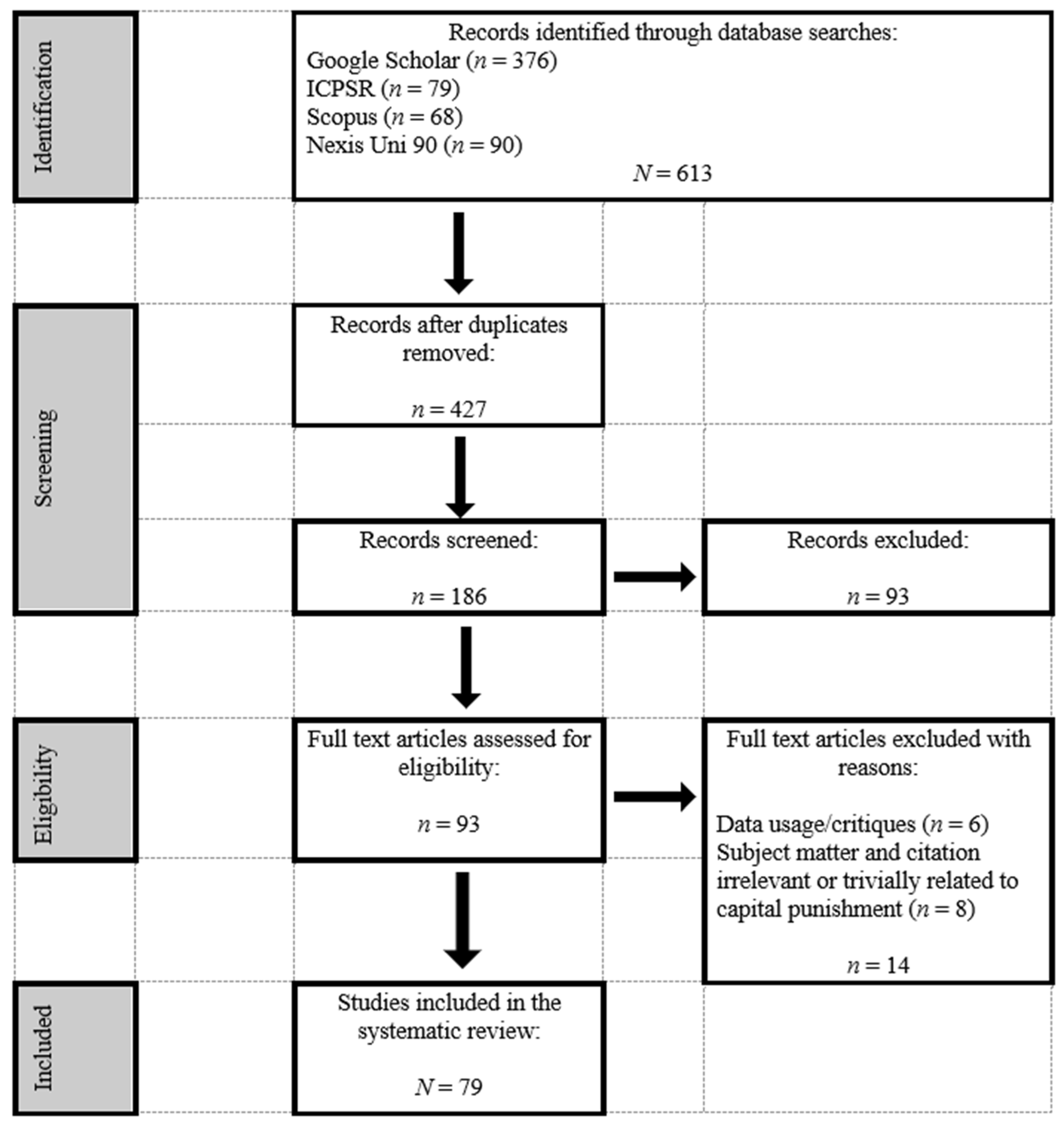

3.1. Selection of Studies

3.2. Themes and Study Characteristics

| Authors and Years of Publication | Sample n and/or Study Description (Research Designs in Parentheses) | Study Time Frames |

|---|---|---|

| Schneider & Smykla (1990) * [52] | 60 years examining changes in executions and effects of wars on executions (descriptive) | 1900–1960 |

| Schumacher (1990) * [53] | 128 countries/examining changes in execution over time (descriptive) | 1965–1987 |

| Keil & Vito (1992) * [42] | 87 years examining changes after the Furman decision and the effects of race on executions (quantitative) | 1900–1987 |

| Thomson (1997) [46] | 2028 homicide offenders/examining changes over time and effects of race (quantitative) | 1982–1991 |

| Marvell & Moody (1998) * [48] | 63 years (predicting homicide rates over time) (quantitative) | 1929–1992 |

| Baker (1999) * [28] | 357 executed women/over time (quantitative) | 1632–1984 |

| Duwe, Kovandzic, & Moody (2022) [49] | 888 mass shootings/how shootings over time led to different policy effects (quantitative) | 1976–1999 |

| Vandiver, Giacopassi, & Curley (2003) * [40] | Tennessee’s 1858 slave code and effects thereof (abolitionist) | -- |

| Poveda (2006) * [45] | 85 counties/changes over time with an emphasis on geographic predictors (quantitative) | 1978–2004 |

| Seitz (2006) * | 160 executions/in North Carolina (descriptive) | 1910–1935 |

| DeFronzo et al. (2007) * | 50 states/rates of male serial killings (quantitative) | 1883–1992 |

| Baker (2007) * [29] | History of Native American executions (descriptive) | 1600s– |

| Baker (2008) * [30] | History of enslaved Black women (historical) | 1600s– |

| Denver, Best, & Haas (2008) * [50] | 12 census years (documenting execution methods) (historical) | 1880–2000 |

| Henry (2008) [57] | New Jersey’s experience with the death penalty (historical) | 1600s– |

| LaChance (2009) [56] | The social effects of Charles Starkweather (historical) | 1958– |

| Keil &Vito (2009) * [43] | 68 years/predict lynchings by executions (quantitative) | 1866–1934 |

| Harmon, Acker, & Rivera (2010) * [58] | 276 governor commutations/relationship between politics and executions (quantitative) | 1900–1963 |

| Baker (2012) [31] | 179 lynchings of women/an inventory (descriptive) | 1600s–1940 |

| Acker & Bellandi (2012) [54] | safeguards to protect the innocent with a focus on Maryland (abolitionist) | -- |

| Roth (2012) [55] | 3350 articles/attitudes about homicide (descriptive) | 1600s–1800s |

| Monahan, Vito, & Vito (2021) * [44] | 249 executions and clemencies/changes over time (quantitative) | 1901–2019 |

| Authors and Years of Publication | Sample n and/or Study Description (Design in Parentheses) | Study Time Frames |

|---|---|---|

| Beck, Massey, & Tolnay (1989) * [70] | 48 years/relationship between executions and voting (quantitative) | 1882–1930 |

| Hunter, Ralph, & Marquart (1993) * [41] | 2190 life-term and death-sentenced rapists (descriptive) | 1875–1971 |

| Vandiver & Coconis (2001) * [10] | 150 convictions for first degree murder (descriptive) | 1916–1949 |

| Galliher & Galliher (2001) [71] | 19 legislative sessions discussing capital punishment (descriptive) | 1975–1995 |

| Ramsey (2002) * [72] | 405 first degree murder indictments (quantitative) | 1879–1893 |

| Baker (2003) [59] | Race and the application of the death penalty (abolitionist) | -- |

| Kubik & Moran (2003) * [73] | 842 states and years/gubernatorial elections and executions (quantitative) | 1977–2000 |

| Pfeifer (2003) [74] | Lynchings in the Pacific Northwest (historical) | 1882–1902 |

| Shepherd (2004) [75] | 13,059 monthly murder rates/effects of the death penalty on deterrence (quantitative) | 1977–1999 |

| Ramsey (2006) [19] | History of IPV homicide and capital punishment (historical) | 1880–1920 |

| Kreitzberg & Richter (2007) [37] | Lethal injections as constitutional or not (abolitionist) | -- |

| Marcus (2007) [38] | Status of capital punishment in the world (abolitionist) | -- |

| Bessler (2009) [61] | Abolitionist movements in the U.S. (abolitionist) | -- |

| Rapaport & Streib (2009) [21] | 24 executed women in North Carolina and current day (descriptive) | 1720–1984 |

| Martin (2010) [39] | New Jersey’s repeal of death penalty (abolitionist) | -- |

| Kendall & Tamura (2010) * [76] | 1409 panel data of 32 states/predicting murder rates (quantitative) | 1957–2002 |

| Siena (2010) [66] | Louisiana’s death penalty statute (abolitionist) | -- |

| Ramsey (2011) [20] | History of IPV homicide/capital punishment (historical) | 1860–1930 |

| Schick (2011) [65] | Lethal injections as cruel and unusual (abolitionist) | -- |

| Adger & Weiss (2011) * [69] | 431 death sentences since Gregg v. Georgia (quantitative) | 1976– |

| Pierce & Radelet (2011) [77] | 191 first degree murder in East Baton Rouge Parish (quantitative) | 1990–2008 |

| Linde (2011) * [78] | 183 executed juveniles and racial discrimination (descriptive) | 1642–2003 |

| Warden (2012) [63] | Illinois’s experience with abolishing the death penalty (abolitionist) | -- |

| Sarat et al. (2013) * [79] | 2477 newspaper articles of “botched executions” and how they have contributed little to abolitionism (descriptive) | 1900–2010 |

| Thaxton (2013) [80] | 400 cases in which prosecutors sought the death penalty (quantitative) | 1993–2000 |

| Compa (2014) [81] | Importance of civil litigation (abolitionist) | -- |

| Smith (2014) [68] | The military and its participation in the death penalty as challenging state legitimacy (abolitionist) | -- |

| Baumgartner & Lyman (2015) [82] | 241 Louisiana death verdict cases/finding 316 victims of whom only 20% were Black males (quantitative) | 1976–2015 |

| Mills, Dorn, & Hritz (2016) [83] | 2295 juveniles sentenced to life without parole/examination of policies and practice (descriptive) | 2015 |

| Baumgartner et al. (2016) * [84] | 475 counties and the federal government/geography and executions (quantitative) | 1608–2015 |

| LaChance (2017) * [85] | 941 execution stories/elite, journalists, etc. attitudes about the death penalty (descriptive) | 1915–1940 |

| Kovarsky (2019) [64] | How the U.S. decides to execute using criteria, like future dangerousness, that are in effect arbitrary (abolitionist) | -- |

| Klein (2021) [62] | Focus on Virginia with the abolition of the death penalty (abolitionist) | -- |

| Meyn (2021) [60] | How Jim Crow is still embedded in and affects the judicial system (abolitionist) | -- |

| Klein (2022) [67] | Law enforcement’s participation in capital punishment and maintaining state legitimacy (abolitionist) | -- |

| Linders (2022) | The move from public to private executions (historical) | 1833–1937 |

| LaChance (2023) * [86] | 667 news articles/of male executions finding white men received coverage that was more respectful (quantitative) | 1877–1936 |

| Jarvis (2023) [87] | The mutiny murder case on the slave ship Enterprise (historical) | 1886 |

| Authors and Dates of Publication | Sample n and/or Study Description (Design in Parentheses) | Study Time Frames |

|---|---|---|

| Harries (1993) * [97] | 3961 executions in the United States (quantitative) | 1930–1987 |

| Harries (1995) * [98] | 13,329 executions/related to race, place, and murder rates in the United States (quantitative) | 1608–1985 |

| Aguirre & Baker (1997) * [99] | 244 executed Hispanic Americans/building on the Espy dataset by clarifying ethnicities (descriptive) | 1795–1987 |

| Aguirre & Baker (1999) * [100] | 1749 executions of slaves/use of Espy dataset to explain why slaves were executed (e.g., slave revolts) (descriptive) | 1641–1865 |

| Reid (2008) * [90] | 810 executed persons/the relationship to the number of lynchings (quantitative) | 1930–1935 |

| Leigh (2008) [104] | 61 years of panel data/governor impact on policies regarding (quantitative) | 1941–2002 |

| Adler (2015) [91] | 2100 homicide cases in New Orleans (descriptive) | 1920–1940s |

| Linders (2015) * [96] | 1800 execution stories/audience and gender (historical) | 1830–1920 |

| Caldararo (2016) [101] | Prisons and death penalty impact on crime (historical) | 1800s– |

| Christian (2017) * [92] | 13,475 lynchings in 275 southern counties (quantitative) | 1880–1930 |

| Baumgartner et al. (2018) [103] | 475 counties in 35 states/predicting homicides (quantitative) | 1977–2014 |

| Adler (2019) [105] | Relationship between Jim Crow and the death penalty (historical) | 1920–1945 |

| Beck & Tolnay (2019) [93] | 3767 lynchings in 11 states involving torture and desecration (descriptive) | 1877–1950 |

| Eriksson (2020) * [102] | 879 counties/Black incarceration rates (quantitative) | 1920–1940 |

| Musgrave (2020) * [106] | 1157 state police agencies adopted by year (quantitative) | 1905–1941 |

| Adler (2021) [94] | 2188 cases of homicide in New Orleans (historical) | 1920–1925 |

| Depew & Swensen (2022)* [107] | 189 years of data from states with gun policies/effect of gun policies on gun-related deaths (quantitative) | 1900–1920 |

| Linders (2022) * [89] | 632 news articles of executed men and women/emphasis on gendered choices in execution garb (historical) | 1840–1940 |

| Grosjean, Masera, & Yousaf (2023) * [95] | 35 million traffic stops in 142 counties of Trump rallies/effect of historical racial violence (quantitative) | 2015–2017 |

| Ward (2023) * [108] | 213 Northeastern counties/arrest rates (quantitative) | 2010–2014 |

3.3. The Research Questions

3.3.1. To What Extent, and for What Purpose, Is the Espy File Data Used in Academic Research?

3.3.2. How Prevalent and What Approach Is Taken for Those Studies Identified as “Gendered, “Raced”, or Utilize Intersectional Frameworks?

3.3.3. Are There Differences among Men and Women Scholars in Research Focus and Methodology?

4. Discussion

4.1. Questioning the Data

4.2. “A Minor Citation”—The Remaining 38 Studies

5. Implications and Conclusions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Donohue, J.J. Empirical analysis and the fate of capital punishment. Duke J. Const. Law Public Policy 2016, 11, 51–106. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, T.; Pason, A.; Wiecko, F.; Brace, B. Comparing criminologists’ views on crime and justice issues with those of the general public. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2018, 29, 443–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DPIC. Executions in the U.S. 1608–2002: The Espy File. Execution Database. Death Penalty Information Center. Available online: https://deathpenaltyinfo.org/database/executions (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Espy, M.W.; Smykla, J.O. Executions in the United States, 1608–2002: The Espy File (ICPSR 8451) [Data Set]; ICPSR: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eschels, B. Data & the death penalty: Exploring the question of national consensus against executing emerging adults in conversation with Andrew Michael’s a decent proposal: Exempting eighteen-to-twenty-year-olds from the death penalty. Harbinger 2016, 40, 147–153. [Google Scholar]

- Blackman, P.H.; McLaughlin, V. The Espy file on American executions: User beware. Homicide Stud. 2011, 15, 209–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.V. Women and Capital Punishment in the United States: An Analytical History; McFarland & Company: Jefferson, NC, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Page, M.J.; Moher, D.; Bossuyt, P.M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Shamseer, L.; Tetzlaff, J.M.; Akl, E.A.; Brennan, S.E.; et al. PRISMA 2020 explanation and elaboration: Updated guidance and exemplars for reporting systematic reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moher, D.; Liberati, A.; Tetzlaff, J.; Altman, D.G. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. Ann. Intern. Med. 2009, 151, 264–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandiver, M.; Coconis, M. Sentenced to the punishment of death: Pre-Furman capital crimes and executions in Shelby County, Tennessee. Univ. Memphis Law Rev. 2001, 31, 861. [Google Scholar]

- Laska, L.L. Fact-Based death penalty research. Tenn. J. Law Policy 2014, 4, 103–114. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Masculinities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Messerschmidt, J. Crime as Structured Action: Doing Masculinities, Race, Class, Sexuality, and Crime; Rowman & Littlefield: Lanham, MD, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Harris, A.P. Gender, violence, race, and criminal justice. Stanf. Law Rev. 2000, 52, 777–807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crenshaw, K. Demarginalizing the intersection of race and sex: A black feminist critique of antidiscrimination doctrine, feminist theory and antiracist politics. Univ. Chic. Leg. Forum 1989, 1, 139–167. [Google Scholar]

- Crenshaw, K. Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanf. Law Rev. 1991, 43, 1241–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, R. Gender and Power; Allen and Unwin: Sydney, Australia, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wilkins, P. Stories that kill: Masculinity and capital prosecutors’ closing arguments. Clevel. State Law Rev. 2023, 71, 1147–1195. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, C.B. Intimate homicide: Gender and crime control, 1880–1920. Univ. Colo. Law Rev. 2006, 77, 101–192. [Google Scholar]

- Ramsey, C.B. Domestic violence and state intervention in the American West and Australia, 1860–1930. Indiana Law J. 2011, 86, 185–254. [Google Scholar]

- Rapaport, E.; Streib, V. Death penalty for women in North Carolina. Elon Law Rev. 2009, 1, 65–94. [Google Scholar]

- Schmuhl, M.; Mills, C.E.; Silva, J.; Capellan, J. Racial and gender threat and the death penalty: A county-level examination of sociopolitical factors influencing death sentences. Crim. Justice Policy Rev. 2023, 34, 161–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, N. What to expect when you’re no longer expecting: How states use concealment and abuse of a corpse statutes against women. Columbia J. Gend. Law 2021, 40, 167–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeffer Billauer, B. Abortion, moral law, and the first amendment: The conflict between fetal rights & freedom of religion. William Mary J. Race Gend. Soc. Justice 2017, 23, 271. [Google Scholar]

- NDPA. National Death Penalty Archive Collections. M. E. Grenander Department of Special Collections & Archives at the University of Albany. Available online: https://archives.albany.edu/description/repositories/ndpad (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Espy, M.W.M. Watt Espy Papers, 1730–2008. M.E. Grenander Department of Special Collections and Archives; University at Albany, State University of New York: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- The Espy Project. The Espy Project Execution Records: Telling the Stories of over 15,000 Individuals Executed in What Is Now the United States Since 1608. M.E. Grenander Special Collections & Archives; University of Albany: Albany, NY, USA. Available online: https://archives.albany.edu/espy/ (accessed on 26 September 2024).

- Baker, D.V. A descriptive profile and socio-historical analysis of female executions in the U.S.: 1632–1997. Women Crim. Justice 1999, 10, 57–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.V. American Indian executions in historical context. Crim. Justice Stud. 2007, 20, 315–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.V. Black female executions in historical context. Crim. Justice Rev. 2008, 33, 64–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.V. Female lynchings in the United States: Amending the historical record. Race Justice 2012, 2, 356–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill-Collins, P. Black Feminist Thought: Knowledge, Consciousness, and the Politics of Empowerment; Unwin Hyman: Boston, MA, USA, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Crittenden, C.; Gateley, H.; Policastro, C.; McGuffee, K. Exploring how gender and sex are measured in criminology and victimology: Are we measuring what we say we are measuring? Women Crim. Justice 2022, 32, 205–218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, A.; Casanova, E.; Shupe, K. Dressed for death: Gender, respectability, and resistance at the gallows. Symb. Interact. 2022, 45, 211–236. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldberg, G.; Bunn, G. Balancing Fairness & (and) Finality: A Comprehensive Review of the Texas Death Penalty. Tex. Rev. Law Policy 2000, 5, 49. [Google Scholar]

- Waldo, G.P.; Myers, W. Criminological research and the death penalty: Has research by criminologists impacted capital punishment practices? Am. J. Crim. Justice 2019, 44, 536–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreitzberg, E.; Richter, D. But can it be fixed-A look at constitutional challenges to lethal injection executions. Santa Clara Law Rev. 2007, 47, 445–510. [Google Scholar]

- Marcus, P. Capital punishment in the United States and beyond. Melb. Univ. R56law Rev. 2007, 31, 837–872. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, R.J. Killing capital punishment in New Jersey: The first state in modern history to repeal its death penalty statute. Univ. Toledo Law Rev. 2010, 41, 485–544. [Google Scholar]

- Vandiver, M.; Giacopassi, D.J.; Curley, M.S. The Tennessee Slave Code: A legal antecedent to inequities in modern capital cases. J. Ethn. Crim. Justice 2003, 1, 67–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, R.J.; Ralph, P.H.; Marquart, J. The death sentencing of rapists in Pre-Furman Texas (1942–1971): The racial dimension. Am. J. Crim. Law 1993, 20, 313–338. [Google Scholar]

- Keil, T.J.; Vito, G.F. The effects of the Furman and Gregg decisions on black-white execution ratios in the South. J. Crim. Justice 1992, 20, 217–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keil, T.J.; Vito, G.F. Lynching and the Death Penalty in Kentucky, 1866–1934: Substitution or Supplement? J. Ethn. Crim. Justice 2009, 7, 53–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monahan, E.; Vito, A.G.; Vito, G.F. A comparison of executions and death to life commutations in Kentucky, 1901–2019. Prison J. 2021, 101, 591–608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poveda, T.G. Geographic Location, Death Sentences and Executions in Post-Furman Virginia. Punishm. Soc. 2006, 8, 423–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomson, E. Discrimination and the death penalty in Arizona. Crim. Justice Rev. 1997, 1, 65–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeFronzo, J.; Ditta, A.; Hannon, L.; Prochnow, J. Male serial homicide: The influence of cultural and structural variables. Homicide Stud. 2007, 11, 3–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvell, T.; Moody, C. The impact of out-of-state prison population on state homicide rates: Displacement and free-rider effects. Criminology 1998, 36, 513–536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duwe, G.; Kovandzic, T.; Moody, C.E. The impact of right-to-carry concealed firearm laws on mass public shootings. Homicide Stud. 2022, 6, 271–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denver, M.; Best, J.; Haas, K.C. Methods of execution as institutional fads. Punishm. Soc. 2008, 10, 227–252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seitz, T.N. Electrocution and the Tar Heel state: The advent and demise of a southern sanction. Am. J. Crim. Justice 2006, 31, 103–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneider, V.W.; Smykla, J.O. War and capital punishment. J. Crim. Justice 1990, 18, 253–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Schumacher, J.E. An international look at the death penalty. Int. J. Comp. Appl. Crim. Justice 1990, 14, 307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acker, J.R.; Bellandi, R. Firmament or folly? Protecting the innocent, promoting capital punishment, and the paradoxes of reconciliation. Justice Q. 2012, 29, 287–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roth, R. Measuring feelings and beliefs that may facilitate (or deter) homicide: A research note on the causes of historic fluctuations in homicide rates in the United States. Homicide Stud. 2012, 16, 197–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lachance, D. Executing Charles Starkweather: Lethal punishment in an age of rehabilitation. Punishm. Soc. 2009, 11, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henry, J.S. New Jersey’s road to abolition. Justice Syst. J. 2008, 29, 408–422. [Google Scholar]

- Harmon, T.R.; Acker, J.R.; Rivera, C. The power to be lenient: Examining New York governors’ capital case clemency decisions. Justice Q. 2010, 27, 742–764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, D.V. Criminal profiling: Purposeful discrimination in capital sentencing. J. Law Soc. Chall. 2003, 5, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Meyn, I. Constructing separate and unequal courtrooms. Ariz. Law Rev. 2021, 63, 1–44. [Google Scholar]

- Bessler, J.D. Revisiting Beccaria’s vision: The enlightenment, America’s death penalty, and the abolition movement. Northwestern J. Law Soc. Policy 2009, 4, 195–328. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A.L. The beginning of the End: Abolishing capital punishment in Virginia. Wash. Lee Law Rev. Online 2021, 77, 375–386. [Google Scholar]

- Warden, R. How and why Illinois abolished the death penalty. Minn. J. Law Inequal. 2012, 30, 245–286. [Google Scholar]

- Kovarsky, L. The American Execution Queue. Stanf. Law Rev. 2019, 71, 1163–1228. [Google Scholar]

- Schick, B. Lethal injection, cruel and unusual? Establishing a demonstrated risk of severe pain: Morales v. Cate, 623 F. 3d 828 (9th Cir.). West. State Univ. Law Rev. 2011, 38, 173–190. [Google Scholar]

- Siena, B. Kennedy v. Louisiana reaffirms the necessity of revising the eighth amendment’s evolving standards of decency analysis. Regent Univ. Law Rev. 2010, 22, 259–289. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, A. When police volunteer to kill. Fla. Law Rev. 2022, 74, 205–266. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, C. Fair and impartial: Military jurisdiction and the decision to seek the death penalty. Univ. Miami Natl. Secur. Armed Confl. Law Rev. 2014, 5, 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adger, J.; Weiss, C. Why place matters: Exploring County level variations in death sentencing in Alabama. Mich. State Law Rev. 2011, 2011, 659–705. [Google Scholar]

- Beck, E.M.; Massey, J.L.; Tolnay, S.E. The gallows, the mob, and the vote: Lethal sanctioning of Blacks in North Carolina and Georgia, 1882 to 1930. Law Soc. Rev. 1989, 23, 317–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galliher, J.M.; Galliher, J.F. A “commonsense” theory of deterrence and the “ideology” of science: The New York state death penalty debate. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 2001, 92, 307–334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ramsey, C.B. The Discretionary power of ‘public’ prosecutors in historical perspective. Am. Crim. Law Rev. 2002, 39, 1309. [Google Scholar]

- Kubik, J.D.; Moran, J.R. Lethal Elections: Gubernatorial politics and the timing of executions. J. Law Econ. 2003, 46, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pfeifer, M.J. “Midnight Justice”: Lynching and law in the Pacific Northwest. Pac. Northwest Q. 2003, 94, 83–92. [Google Scholar]

- Shepherd, J.M. Murders of passion, execution delays, and the deterrence of capital punishment. J. Leg. Stud. 2004, 33, 283–322. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kendall, T.D.; Tamura, R. Unmarried fertility, crime, and social stigma. J. Law Econ. 2010, 53, 185–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pierce, G.L.; Radelet, M.L. Death sentencing in East Baton Rouge Parish, 1990–2008. La. Law Rev. 2011, 71, 647–673. [Google Scholar]

- Linde, R. From rapists to superpredators: What the practice of capital punishment says about race, rights and the American child. Int. J. Child. Rights 2011, 19, 127–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarat, A.; Blumstein, K.; Jones, A.; Richard, H.; Sprung-Keyser, M.; Weaver, R. Botched executions and the struggle to end capital punishment: A twentieth-century story. Law Soc. Inq. 2013, 38, 694–720. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaxton, S. Leveraging death. J. Crim. Law Criminol. 2013, 103, 475. [Google Scholar]

- Compa, E. Litigating civil rights on death row: A Louisiana perspective. Loyola J. Public Interest Law 2014, 15, 293–317. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Lyman, T. Race-of-victim discrepancies in homicides and executions, Louisiana 1976–2015. Loyola J. Public Interest Law 2015, 17, 129–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, J.R.; Dorn, A.M.; Hritz, A.C. Juvenile life without parole in law and practice: Chronicling the rapid change underway. Am. Univ. Law Rev. 2016, 65, 535–606. [Google Scholar]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Gram, W.; Johnson, K.R.; Krishnamurthy, A.; Wilson, C.P. The geographic distribution of U.S. executions. Duke J. Const. Law Public Policy 2016, 11, 1–33. [Google Scholar]

- LaChance, D. Executing humanity: Legal consciousness and capital punishment in the United States, 1915–1940. Law Hist. Rev. 2017, 35, 929–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LaChance, D. The death penalty in black and white: Execution coverage in two Southern newspapers, 1877–1936. Law Soc. Inq. 2023, 48, 999–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jarvis, R.M. The Schooner Enterprise: A forgotten Key West murder case. Br. J. Am. Leg. Stud. 2023, 12, 195–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howard, J. Defending person and reputation: Efforts to end extralegal violence in Western Virginia, 1890–1900. Am. J. Leg. Hist. 2018, 58, 167–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, A. The execution spectacle and state legitimacy: The changing nature of the American execution audience, 1833–1937. Law Soc. Rev. 2022, 36, 607–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reid, L.W. Disaggregating the effects of racial and economic inequality on early twentieth-century execution rates. Sociol. Spectr. 2008, 28, 160–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.S. Less crime, more punishment: Violence, race, and criminal justice in early twentieth-century America. J. Am. Hist. 2015, 102, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christian, C. Lynchings, labour, and cotton in the US south: A reappraisal of Tolnay and Beck. Explor. Econ. Hist. 2017, 66, 106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beck, E.M.; Tolnay, S.E. Torture and desecration in the American South, an exclamation point on white supremacy, 1877–1950. Soc. Curr. 2019, 6, 319–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.S. “Justice is something that is unheard of for the average negro”: Racial disparities in New Orleans criminal justice, 1920–1945. J. Soc. Hist. 2021, 54, 1213–1231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosjean, P.; Masera; Yousaf, H. Inflammatory political campaigns and racial bias in policing. Q. J. Econ. 2023, 138, 413–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linders, A. What daughters, what wives, what mothers, think you, they are? J. Hist. Sociol. 2015, 28, 135–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, K.D. The historical geography of homicide in the U.S., 1935–1980. Geoforum J. Phys. Hum. Reg. Geosci. 1993, 16, 73–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harries, K.D. The last walk: A geography of execution in the United States, 1786–1985. Political Geogr. 1995, 14, 473–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A., Jr.; Baker, D.V. A descriptive profile of Mexican American executions in the Southwest. Soc. Sci. J. 1997, 34, 389–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aguirre, A., Jr.; Baker, D.V. Slave executions in the United States: A descriptive analysis of social and historical factors. Soc. Sci. J. 1999, 36, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caldararo, N. Human sacrifice, capital punishment, prisons & justice: The function and failure of punishment and search for alternatives. Hist. Soc. Res. 2016, 41, 322–346. [Google Scholar]

- Eriksson, K. Education and incarceration in the Jim Crow South: Evidence from Rosenwald schools. J. Hum. Resour. 2020, 55, 43–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumgartner, F.R.; Box-Steffensmeier, J.M.; Campbell, B.W. Event dependence in U.S. executions. PLoS ONE 2018, 13, e0190244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leigh, A. Estimating the impact of gubernatorial partisanship on policy settings and economic outcomes: A regression discontinuity approach. Eur. J. Political Econ. 2008, 24, 256–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adler, J.S. “To stay the murderer’s hand and the rapist’s passions, and for the safety and security of civil society:” The emergence of racial disparities in capital punishment in Jim Crow New Orleans. Am. J. Leg. Hist. 2019, 59, 297–323. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Musgrave, P. Bringing the state police in: The diffusion of U.S. statewide policing agencies, 1905–1941. Stud. Am. Political Dev. 2020, 34, 3–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Depew, B.; Swensen, I. Effect of concealed-carry and handgun restrictions on gun-related deaths: Evidence from the Sullivan Act of 1911. Econ. J. 2022, 132, 2118–2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, M. Legacies of resistance and resilience: Antebellum free African Americans and contemporary minority social control in the Northeast. Soc. Forces 2023, 102, 496–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, J.H. Creole and unusual punishment-A Tenth Anniversary examination of Louisiana’s capital rape statute. Villanova Law Rev. 2006, 51, 417–457. [Google Scholar]

- Schulze, C. Dehumanization through degendering the death row inmate: A systematic review of the research. OMEGA-J. Death Dying 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nath, S. Examining militarized masculinity, violence and conflict: Male survivors of torture in international politics. Int. Stud. 2022, 59, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chesney-Lind, M.; Morash, M. Transformative feminist criminology: A critical re-thinking of a discipline. Crit. Criminol. 2013, 21, 287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federman, C.H.; Holmes, D. Breaking bodies into pieces: Time, torture and bio-power. Crit. Criminol. 2005, 13, 327–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robson, R. Lesbianism and the death penalty: A “hard core” case. Women’s Stud. Q. 2004, 32, 181–191. [Google Scholar]

- Joseph, E. Corcoran v. State of Indiana. Supreme Court of Indiana Case Nos. 02S00-0508-PD-350 24S-SD-222 (28 June 2024). Available online: https://www.in.gov/courts/files/order-other-2024-24S-SD-222.pdf (accessed on 26 September 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schulze, C. Explaining Gender Neutrality in Capital Punishment Research by Way of a Systematic Review of Studies Citing the ‘Espy File’. Sexes 2024, 5, 521-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5040036

Schulze C. Explaining Gender Neutrality in Capital Punishment Research by Way of a Systematic Review of Studies Citing the ‘Espy File’. Sexes. 2024; 5(4):521-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5040036

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchulze, Corina. 2024. "Explaining Gender Neutrality in Capital Punishment Research by Way of a Systematic Review of Studies Citing the ‘Espy File’" Sexes 5, no. 4: 521-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5040036

APA StyleSchulze, C. (2024). Explaining Gender Neutrality in Capital Punishment Research by Way of a Systematic Review of Studies Citing the ‘Espy File’. Sexes, 5(4), 521-543. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5040036