The Dual-Pathway Model of Respect in Romantic Relationships

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Romantic Commitment

1.2. Dual-Pathway Model of Respect

1.3. Hypotheses

2. Study 1

2.1. Materials and Methods

2.1.1. Participants and Procedure

2.1.2. Measures

2.2. Data Analysis

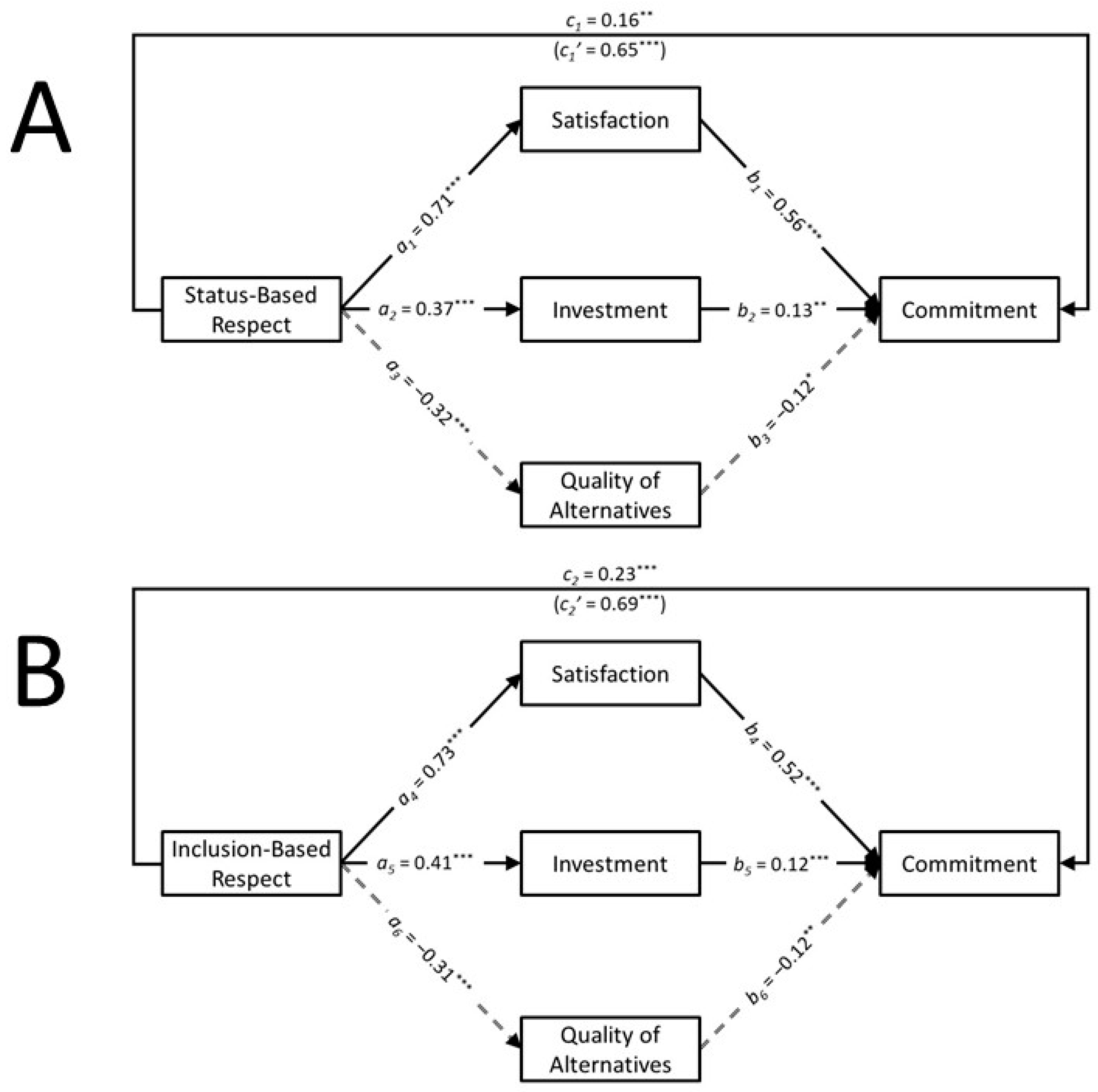

2.3. Results

2.4. Discussion

3. Study 2

3.1. Materials and Methods

3.1.1. Participants and Procedure

3.1.2. Measures

3.2. Data Analysis

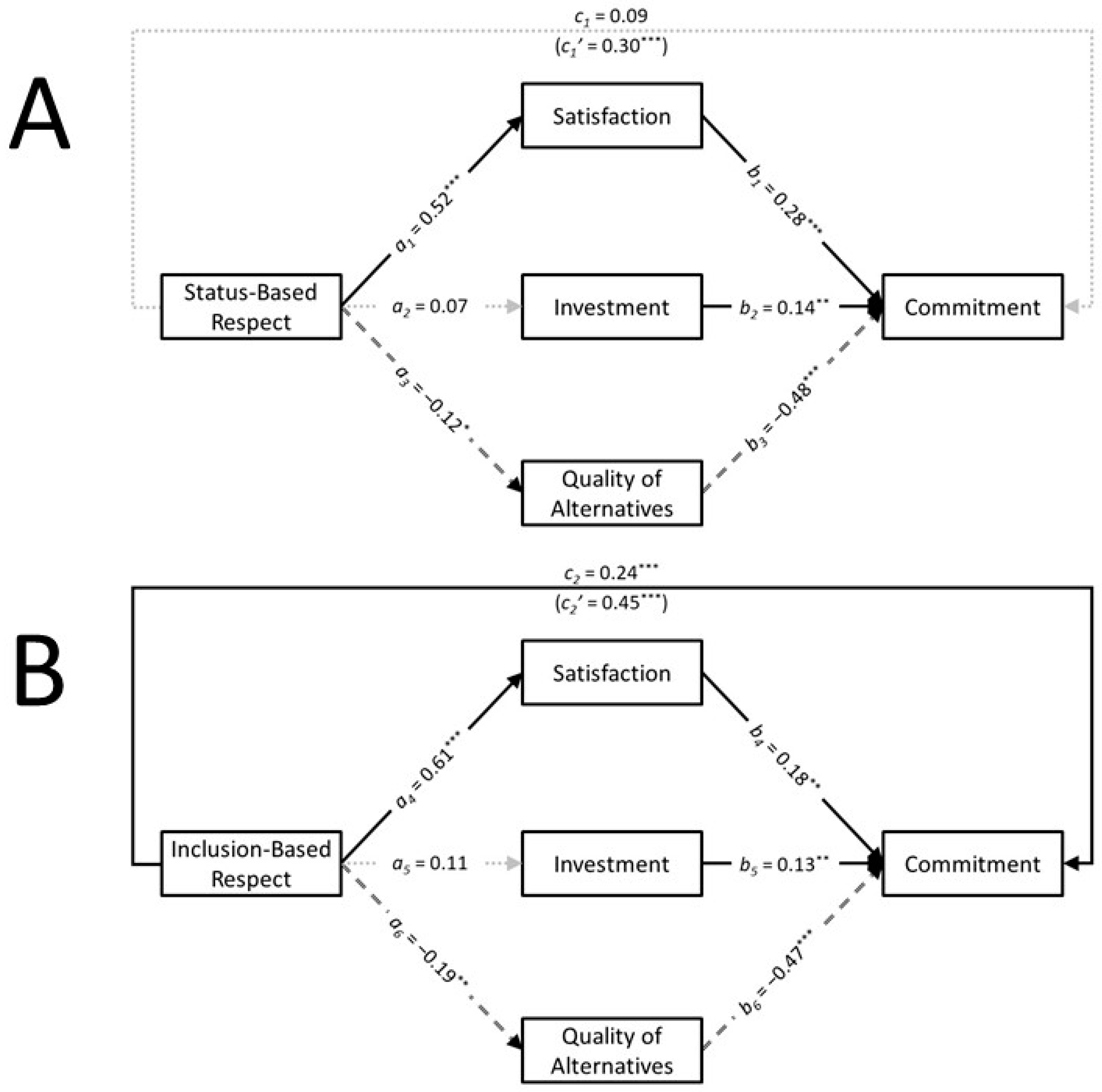

3.3. Results

3.4. Discussion

4. Study 3

4.1. Materials and Methods

4.1.1. Participants and Procedure

4.1.2. Measures

4.2. Data Analysis

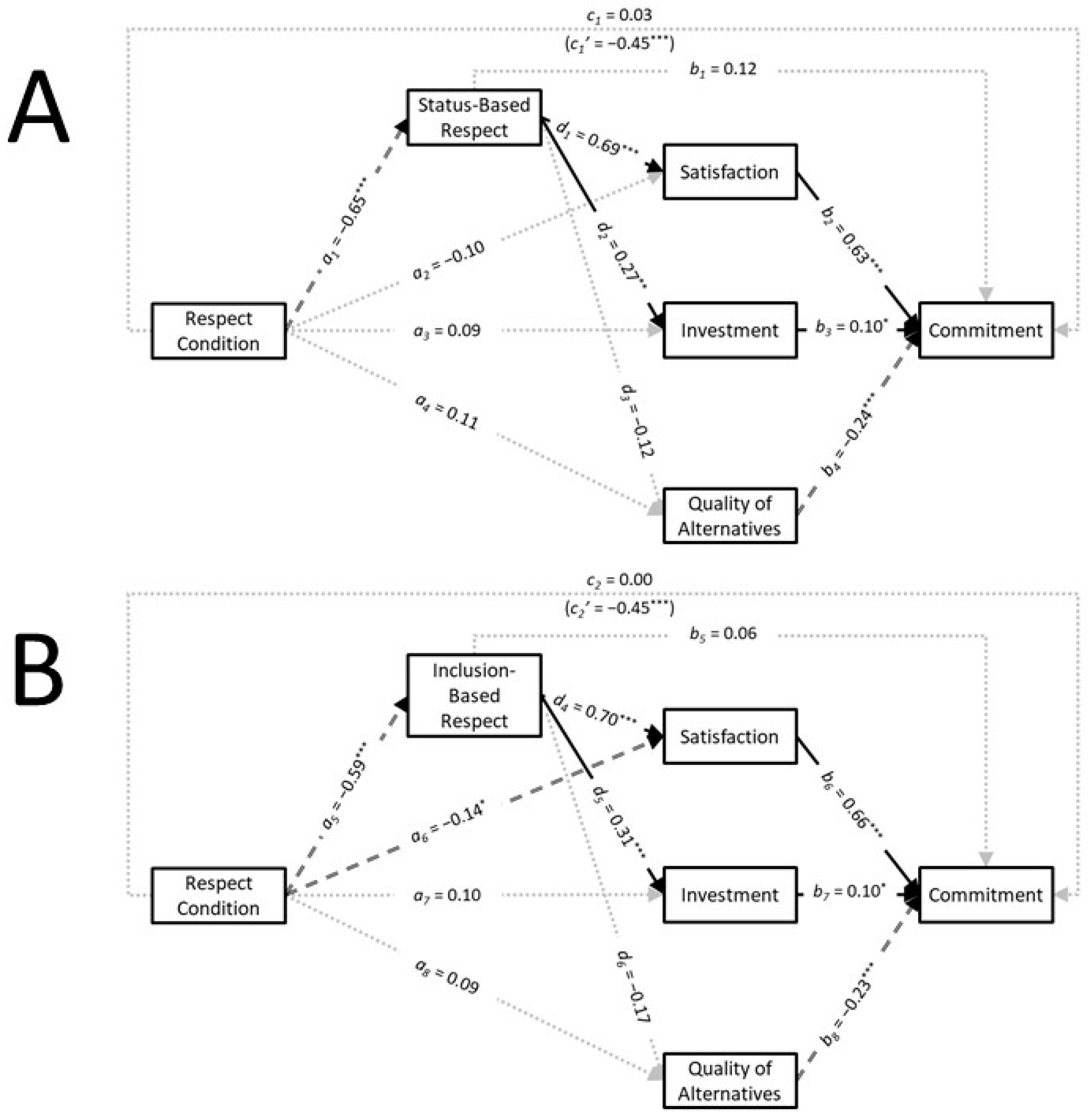

4.3. Results

4.4. Discussion

5. General Discussion

5.1. Limitations

5.2. Future Directions

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Frei, J.R.; Shaver, P.R. Respect in close relationships: Prototype definition, self- report assessment, and initial correlates. Pers. Relatsh. 2002, 9, 121–139. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, S.S.; Hendrick, C. Measuring respect in close relationships. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 2006, 23, 881–899. [Google Scholar]

- Jackson, L.M.; Esses, V.M.; Burris, C.T. Contemporary sexism and discrimination: The importance of respect for men and women. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2001, 27, 48–61. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R.; Smith, H.J. Justice, Social Identity, and Group Processes; Lawrence Erlbaum: Mahwah, NJ, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Rothers, A.; Cohrs, J.C. What makes people feel respected? Toward an integrative psychology of social worth. Psychol. Rev. 2023, 130, 242–259. [Google Scholar]

- Lehtman, M.J.; Zeigler-Hill, V. Narcissism and job commitment: The mediating role of job-related attitudes. Pers. Individ. Dif. 2020, 157, 109807. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, S.S.; Hendrick, C.; Logue, E.M. Respect and the family. J. Fam. Theor. Rev. 2010, 2, 126–136. [Google Scholar]

- Bagci, S.C.; Turnuklu, A.; Bekmezci, E. Cross-group friendships and psychological well-being: A dual pathway through social integration and empowerment. Br. J. Soc. Psychol. 2018, 57, 773–792. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Huo, Y.J.; Binning, K.R. Why the psychological experience of respect matters in group life: An integrative account. Soc. Pers. Psychol. Compass 2008, 2, 1570–1585. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, Y.J.; Binning, K.R.; Molina, L.E. Testing an integrative model of respect: Implications for social engagement and well-being. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 2010, 36, 200–212. [Google Scholar]

- Li, J.; Fischer, K.W. Respect as a positive self-conscious emotion in European Americans and Chinese. In The Self-Conscious Emotions: Theory and Research; Tracy, J.L., Robins, R.W., Tangney, J.P., Eds.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2007; pp. 224–242. [Google Scholar]

- Kovecses, Z. Emotion Concepts; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Van Quaquebeke, N.; Zenker, S.; Eckloff, T. Find out how much it means to me! The importance of interpersonal respect in work values compared to perceived organizational practices. J. Bus. Ethics 2009, 89, 423–431. [Google Scholar]

- Clarke, N. An integrated conceptual model of respect in leadership. Leadersh. Quart. 2011, 22, 316–327. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler, T.R.; Blader, S.L. Autonomous vs. comparative status: Must we be better than others to feel good about ourselves? Organ. Behav. Human Dec. Process 2002, 89, 813–838. [Google Scholar]

- Hendrick, C.; Hendrick, S.S.; Zacchilli, T.L. Respect and love in romantic relationships. Acta Investigac Psicol. 2011, 1, 316–329. [Google Scholar]

- Owen, J.; Quirk, K.; Manthos, M. I get no respect: The relationship between betrayal trauma and romantic relationship functioning. J. Trauma Dissociation 2012, 13, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Vrabel, J.; Zeigler-Hill, V.; Sauls, D.; McCabe, G. Narcissism and respect in romantic relationships. Self Identity 2021, 20, 216–234. [Google Scholar]

- Gottman, J.M. Why Marriages Succeed or Fail; Simon & Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Wieselquist, J.; Rusbult, C.E.; Foster, C.A.; Agnew, C.R. Commitment, pro-relationship behavior, and trust in close relationships. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1999, 77, 942–966. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult, C.E. Commitment and satisfaction in romantic associations: A test of the Investment Model. J. Exp. Soc. Psychol. 1980, 16, 172–186. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult, C.E. A longitudinal test of the Investment Model: The development (and deterioration) of satisfaction and commitment in heterosexual involvements. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1983, 45, 101–117. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Martz, J.M.; Agnew, C.R. The Investment Model Scale: Measuring commitment level, satisfaction level, quality of alternatives, and investment size. Pers. Relatsh. 1998, 5, 357–387. [Google Scholar]

- Fehr, B. Prototype analysis of the concepts of love and commitment. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1988, 55, 557–579. [Google Scholar]

- Aron, A.; Westbay, L. Dimensions of the prototype of love. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1996, 70, 535–551. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L.E.; Strube, M.J. An assessment of romantic commitment among Black and White dating couples. J. Appl. Soc. Psychol. 1993, 23, 212–225. [Google Scholar]

- Duffy, S.M.; Rusbult, C.E. Satisfaction and commitment in homosexual and heterosexual relationships. J. Homosex. 1986, 12, 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- Le, B.; Agnew, C.R. Commitment and its theorized determinants: A meta–analysis of the Investment Model. Pers. Relatsh. 2003, 10, 37–57. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, Y.H.W.; Rusbult, C.E. Commitment to dating relationships and cross-sex friendships in America and China. J. Soc. Pers. Relatsh. 1995, 12, 7–26. [Google Scholar]

- Rusbult, C.E.; Martz, J.M. Remaining in an abusive relationship: An Investment Model analysis of nonvoluntary dependence. Pers. Soc. Psychol. Bull. 1995, 21, 558–571. [Google Scholar]

- Tran, P.; Judge, M.; Kashima, Y. Commitment in relationships: An updated meta-analysis of the Investment Model. Pers. Relatsh. 2019, 26, 158–180. [Google Scholar]

- Nystrom, P.C. Vertical exchanges and organizational commitments of American business managers. Group. Org. Studies 1990, 15, 296–312. [Google Scholar]

- Turban, D.B.; Jones, A.P.; Rozelle, R.M. Influences of supervisor linking of a subordinate and reward context on the treatment and evaluation of that subordinate. Motiv. Emot. 1990, 14, 215–233. [Google Scholar]

- Brimhall, K.C. Inclusion and commitment as key pathways between leadership and nonprofit performance. Nonprofit Manag. Lead. 2019, 30, 31–49. [Google Scholar]

- Mor Barak, M.E.; Lizano, E.L.; Kim, A.; Duan, L.; Rhee, M.-K.; Hsiao, H.-Y.; Brimhall, K.C. The promise of diversity management for climate of inclusion: A state-of-the-art review and meta-analysis. Human Serv. Organ. Manag. Leadersh. Gov. 2016, 40, 305–333. [Google Scholar]

- Shore, L.M.; Randel, A.E.; Chung, B.G.; Dean, M.A.; Holcombe Ehrhart, K.; Singh, G. Inclusion and diversity in work groups: A review and model for future research. J. Manag. 2011, 37, 1262–1289. [Google Scholar]

- Schoemann, A.M.; Boulton, A.J.; Short, S.D. Determining power and sample size for simple and complex mediation models. Soc. Psychol. Person. Sci. 2017, 8, 379–386. [Google Scholar]

- Mahadevan, N.; Gregg, A.P.; Sedikides, C.; de Waal-Andrews, W.G. Winners, losers, insiders, and outsiders: Comparing hierometer and sociometer theories of self-regard. Front. Psychol. 2016, 7, 334. [Google Scholar]

- Hayes, A.F. Introduction to Mediation, Moderation, and Conditional Process Analysis: A Regression-Based Approach, 2nd ed.; Guilford Press: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows; Version 29.0; [Computer Software]; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- McClelland, G.H.; Judd, C.M. Statistical difficulties of detecting interactions and moderator effects. Psychol. Bull. 1993, 114, 376–390. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Status-based respect | — | |||||

| 2. Inclusion-based respect | 0.89 *** | — | ||||

| 3. Satisfaction | 0.71 *** | 0.73 *** | — | |||

| 4. Investment | 0.37 *** | 0.41 *** | 0.40 *** | — | ||

| 5. Quality of alternatives | −0.31 *** | −0.31 *** | −0.36 *** | −0.20 ** | — | |

| 6. Commitment | 0.65 *** | 0.69 *** | 0.77 *** | 0.44 *** | −0.40 *** | — |

| Mean | 5.90 | 5.85 | 7.08 | 6.02 | 2.91 | 7.31 |

| Standard deviation | 1.12 | 1.04 | 1.14 | 1.43 | 2.09 | 1.22 |

| Skewness | −1.02 | −1.22 | −1.49 | −0.61 | 0.31 | −1.85 |

| Kurtosis | 0.27 | 0.51 | 1.57 | 0.17 | −0.90 | 2.27 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Status-based respect | — | |||||

| 2. Inclusion-based respect | 0.68 *** | — | ||||

| 3. Satisfaction | 0.52 *** | 0.61 *** | — | |||

| 4. Investment | 0.07 | 0.11 | 0.17 ** | — | ||

| 5. Quality of alternatives | −0.12 * | −0.19 ** | −0.21 *** | −0.21 *** | — | |

| 6. Commitment | 0.30 *** | 0.45 *** | 0.44 *** | 0.29 *** | −0.58 *** | — |

| Mean | 5.84 | 5.81 | 6.67 | 6.05 | 3.24 | 7.35 |

| Standard deviation | 0.77 | 0.73 | 1.11 | 1.33 | 1.93 | 0.89 |

| Skewness | −0.74 | −0.93 | −1.14 | −0.75 | 0.37 | −1.45 |

| Kurtosis | 0.66 | 0.86 | 1.45 | −0.02 | −0.75 | 1.17 |

| 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1. Status-based respect | — | 0.79 ** | 0.67 ** | 0.19 | −0.18 | 0.66 ** |

| 2. Inclusion-based respect | 0.88 ** | — | 0.70 ** | 0.25 * | −0.14 | 0.57 ** |

| 3. Satisfaction | 0.60 ** | 0.66 ** | — | 0.36 ** | −0.24 * | 0.77 ** |

| 4. Investment | 0.23 * | 0.25 * | 0.44 ** | — | −0.10 | 0.36 ** |

| 5. Quality of alternatives | −0.04 | −0.14 | −0.42 ** | −0.11 | — | −0.37 ** |

| 6. Commitment | 0.46 ** | 0.53 ** | 0.80 ** | 0.44 ** | −0.57 ** | — |

| Mean disrespect | 3.26 | 3.50 | 3.63 | 4.94 | 2.62 | 5.00 |

| Standard deviation disrespect | 1.71 | 1.63 | 2.70 | 1.92 | 2.24 | 2.46 |

| Skewness disrespect | 0.40 | 0.48 | 0.21 | −0.23 | 0.58 | −0.44 |

| Kurtosis disrespect | −0.73 | −0.64 | −1.28 | −0.58 | −0.64 | −0.86 |

| Mean respect | 5.81 | 5.56 | 6.65 | 5.25 | 1.79 | 7.05 |

| Standard deviation respect | 1.26 | 1.17 | 1.83 | 1.82 | 2.05 | 1.50 |

| Skewness respect | −0.82 | −0.73 | −1.57 | −0.27 | 1.26 | −1.68 |

| Kurtosis respect | −0.71 | −0.73 | 1.71 | −0.61 | 0.88 | 1.77 |

| Disrespect Condition | Respect Condition | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| M | SD | M | SD | t | |

| Status-based respect | 3.26 | 1.71 | 5.81 | 1.26 | −11.60 ** |

| Inclusion-based respect | 3.50 | 1.63 | 5.56 | 1.17 | −9.90 ** |

| Satisfaction | 3.63 | 2.70 | 6.65 | 1.83 | −8.93 ** |

| Investment | 4.94 | 1.92 | 5.25 | 1.82 | −1.13 |

| Quality of alternatives | 2.62 | 2.24 | 1.79 | 2.05 | 2.63 * |

| Commitment | 5.00 | 2.46 | 7.05 | 1.50 | −6.87 ** |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Young, G.; Zeigler-Hill, V. The Dual-Pathway Model of Respect in Romantic Relationships. Sexes 2024, 5, 317-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5030024

Young G, Zeigler-Hill V. The Dual-Pathway Model of Respect in Romantic Relationships. Sexes. 2024; 5(3):317-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5030024

Chicago/Turabian StyleYoung, Gracynn, and Virgil Zeigler-Hill. 2024. "The Dual-Pathway Model of Respect in Romantic Relationships" Sexes 5, no. 3: 317-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5030024

APA StyleYoung, G., & Zeigler-Hill, V. (2024). The Dual-Pathway Model of Respect in Romantic Relationships. Sexes, 5(3), 317-334. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5030024