Comparing Attitudes toward Sexual Consent between Japan and Canada

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Difference in Legal Context between Japan and Canada

1.1.1. Japan

1.1.2. Canada

1.1.3. Law and Social Norms

1.2. Mediational Mechanism

1.3. Hypotheses

- H1: be more likely to perceive the imposition of punishment as appropriate.

- H2: perceive the level of victim’s consent as higher.

- In addition, we hypothesized that the relationship between country and perceived appropriateness of punishment would be mediated by perceived victim’s consent (H3).

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Participants and Procedures

2.2. Development of Scenarios

2.3. Variables

2.3.1. Perceived Appropriateness of Punishment

2.3.2. Perceived Victim’s Consent

2.3.3. Demographic Variables

2.4. Translation

2.5. Analytical Strategy

3. Results

3.1. Sample Characteristics and Descriptive Statistics

3.2. Exploratory Factor Analysis

3.3. Invariance Testing

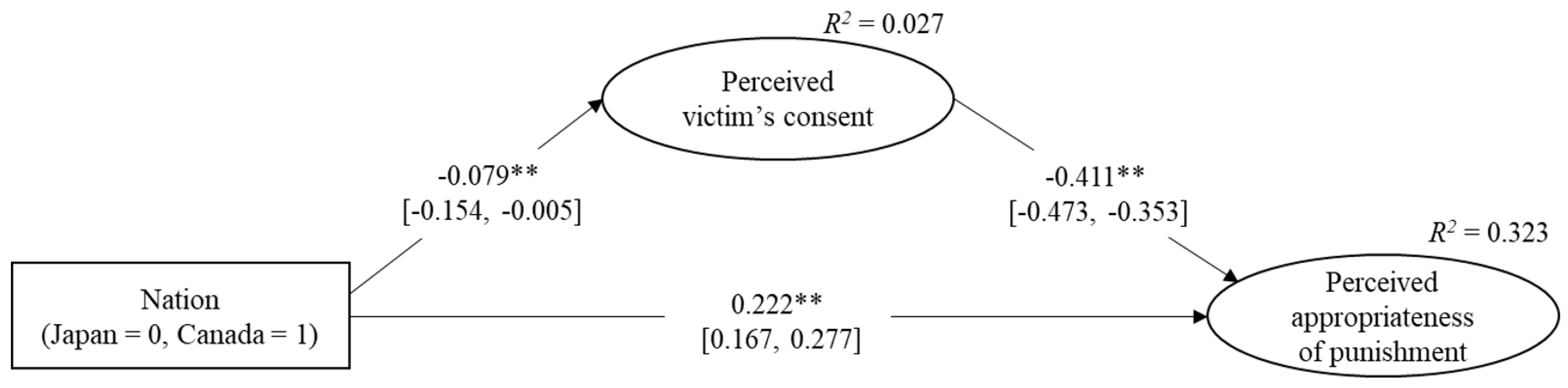

3.4. Mediation Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Overview of the Results

4.2. Contribution of the Present Study

4.3. Limitations

4.4. Future Research Orientation

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Green, S.P. Criminalizing Sex: A Unified Liberal Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Lappi-Seppälä, T. Explaining national differences in the use of imprisonment. In Resisting Punitiveness in Europe? Welfare, Human Rights, and Democracy; Snacken, S., Dumortier, E., Eds.; Routledge: London, UK, 2012; pp. 35–72. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, L.M. Impact: How Law Affects Behavior; Harvard University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Gagnon, J.H.; Simon, W. Sexual Conduct: The Social Sources of Human Sexuality; Aldin: Chicago, IL, USA, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- Beres, M.A. Sexual miscommunication? Untangling assumptions about sexual communication between casual sex partners. Cult. Health Sex. 2010, 12, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Humphreys, T.; Herold, E. Sexual consent in heterosexual relationships: Development of a new measure. Sex Roles 2007, 57, 305–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcantonio, T.L.; Jozkowski, K.N. Assessing how gender, relationship status, and item wording influence cues used by college students to decline different sexual behaviors. J. Sex Res. 2020, 57, 260–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schuller, R.A.; Klippenstine, M.A. The impact of complainant sexual history evidence on jurors’ decisions: Considerations from a psychological perspective. Psychol. Public Policy Law 2004, 10, 321–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternin, S.; McKie, R.M.; Winberg, C.; Travers, R.N.; Humphreys, T.P.; Reissing, E.D. Sexual consent: Exploring the perceptions of heterosexual and non-heterosexual men. Psychol. Sex 2022, 13, 512–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Watamura, E. Comparing negative social reactions to sexual and non-sexual crimes: An experimental study with a Japanese sample. Int. Criminol. 2022, 2, 414–423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Darby, R.; Queiroz, A. The moderating role of ambivalent sexism: The influence of power status on perception of rape victim and rapist. J. Soc. Psychol. 2007, 147, 41–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sprecher, S.; Hatfield, E.; Cortese, A.; Potapova, E.; Levitskaya, A. Token resistance to sexual intercourse and consent to unwanted sexual intercourse: College students’ dating experiences in three countries. J. Sex Res. 1994, 31, 25–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamawaki, N.; Tschanz, B.T. Rape perception differences between Japanese and American college students: On the mediating influence of gender role traditionality. Sex Roles 2005, 52, 379–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukai, T.; Cho, E.; Matsuo, A.; Yuyama, Y.; Tanaka, Y. The relationship between attitudes toward sexual consent and perceived appropriateness of punishment: A comparison of Korea and Japan. Jpn. J. Pers. 2023, 32, 53–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Henrich, J.; Heine, S.J.; Norenzayan, A. The weirdest people in the world? Behav. Brain Sci. 2010, 33, 61–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukai, T.; Garcia Ramirez, D.; Matsuki, Y.; Takenaka, Y.; Watamura, E. Comparing the determinants of punitiveness in Japan and Costa Rica. Int. J. Comp. Appl. Crim. Justice 2023, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shimaoka, M. Seihanzai no hogo houeki oyobi keihou kaisei kosshi heno hihanteki kousatsu [Protected legal interests of sex crime and critical considerations on criminal law amendment]. Keio Law J. 2017, 37, 19–37. [Google Scholar]

- Japan Amends Sex Crime Requirement in Draft Law Revision. Available online: https://sp.m.jiji.com/english/show/24190 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Japan Enforces Revised Penal Code to Clarify Sex Crime Criteria. Available online: https://sp.m.jiji.com/english/show/27319 (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Kamimoto, M. Japan Changed Sexual Assault Laws, Redefined Non-Consensual Intercourse. Available online: https://zenbird.media/japan-changed-sexual-assault-laws-redefined-non-consensual-intercourse (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Negishi, T. Over 40% of Young People Not Clear about Sexual Consent. Available online: https://www.asahi.com/ajw/articles/15026265 (accessed on 4 March 2024).

- Randall, M. Sexual assault law, credibility, and “ideal victims”: Consent, resistance, and victim blaming. Can. J. Women Law 2010, 22, 397–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Institut National de Santé Publique du Québec. Community and Societal Strategies. Available online: https://www.inspq.qc.ca/en/sexual-assault/prevention/community-and-societal-strategies (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Department of Justice. A Definition of Consent to Sexual Activity. Available online: https://www.justice.gc.ca/eng/cj-jp/victims-victimes/def.html (accessed on 18 October 2023).

- Costelloe, M.T.; Chiricos, T.; Buriánek, J.; Gertz, M.; Maier-Katkin, D. The social correlates of punitiveness toward criminals: A comparison of the Czech Republic and Florida. Justice Syst. J. 2002, 23, 191–220. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, S.; Lambert, E.G.; Wang, J.; Saito, T.; Pilot, R. Death penalty views in China, Japan and the U.S.: An empirical comparison. J. Crim. Justice 2010, 38, 862–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Jiang, S.; Williamson, L.C.; Elechi, O.O.; Khondaker, M.I.; Baker, D.N.; Saito, T. Gender and capital punishment views among Japanese and U.S. college students. Int. Crim. Justice Rev. 2016, 26, 337–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lambert, E.G.; Jiang, S. A comparison of Chinese and US college students’ crime and crime control views. Asian J. Criminol. 2006, 1, 37–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unnever, J. Global support for the death penalty. Punishm. Soc. 2010, 12, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrade, C. Sample size and its importance in research. Indian J. Psychol. Med. 2019, 42, 102–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wertheimer, A. Consent to Sexual Relations, 2nd ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Brislin, R.W. Back-translation for cross-cultural research. J. Cross. Cult. Psychol. 1970, 1, 185–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirschfeld, G.; von Brachel, R. Multiple-group confirmatory factor analysis in R: A tutorial in measurement invariance with continuous and ordinal indicators. Pract. Assess. Res. Eval. 2014, 19, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, R.; Gore, P.A. A brief guide to structural equation modeling. Couns. Psychol. 2006, 34, 719–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baron, R.M.; Kenny, D.A. The moderator-mediator variable distinction in social psychological research: Conceptual, strategic, and statistical considerations. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1986, 51, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hayes, A.F. Beyond Baron and Kenny: Statistical mediation analysis in the new millennium. Commun. Monogr. 2009, 76, 408–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosseel, Y. lavaan: An R package for structural equation modeling. J. Stat. Softw. 2012, 48, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, D.T. Is rape a crime in Japan? Int. J. Asian Stud. 2024, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lancaster, R.N. Sex Panic and the Punitive State; University of California Press: Berkeley, CA, USA, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Chiang, L.C.; Huang, C.Y. Use of pirated compact discs on four college campuses: A perspective from theory of planned behavior. Psychol. Rep. 2007, 101, 361–364. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall, E.; Bouffard, J.A.; Miller, H. Pornography use and sexual coercion: Examining the mediation effect of sexual arousal. Sex. Abus. J. Res. Treat. 2021, 33, 552–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Oosten, J.M.F.; Peter, J.; Vandenbosch, L. Adolescents’ sexual media use and willingness to engage in casual sex: Differential relations and underlying processes. Hum. Commun. Res. 2017, 43, 127–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, L.M. Understanding the role of entertainment media in the sexual socialization of American youth: A review of empirical research. Dev. Rev. 2003, 23, 347–388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pioch, C.; Aizawa, I. La violence sexuelle, un problème sociétal majeur mondial, une situation unique: Le Japon [Sexual violence, a major global societal problem, a unique situation: Japan]. Enjeux société Approch. Transdiscipl. 2022, 9, 183–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- About Flower Demo. Available online: https://www.flowerdemo.org/english (accessed on 10 December 2023).

| Variable | Japan (n = 1125) | Canada (n = 1125) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Age | ||||

| 20s | 228 | 20.3% | 228 | 20.3% |

| 30s | 241 | 21.4% | 241 | 21.4% |

| 40s | 215 | 19.1% | 215 | 19.1% |

| 50s | 232 | 20.6% | 232 | 20.6% |

| 60s | 209 | 18.6% | 209 | 18.6% |

| Gender | ||||

| Woman | 569 | 50.6% | 569 | 50.6% |

| Man | 556 | 49.4% | 556 | 49.4% |

| Other | 0 | 0.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| Language | ||||

| Japanese | 1000 | 100.0% | 0 | 0.0% |

| English | 0 | 0.0% | 1019 | 90.6% |

| French | 0 | 0.0% | 106 | 9.4% |

| Punishment | Consent | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Canada | Japan | Canada | ||

| pun4 con4 | A proposed intercourse; B accepted on condition that A used a condom. A said “OK” and then penetrated B without a condom. B told A to withdraw. A refused until he ejaculated. | 0.79 | 0.74 | 0.64 | 0.73 |

| pun1 con1 | A overpowered B physically, held her down despite B’s attempts to resist, and threatened her with additional force if she continued to resist. | 0.76 | 0.62 | 0.82 | 0.76 |

| pun6 con6 | A and B had dated, but B had rebuffed A’s advances. On this occasion, B was severely intoxicated, although she had not passed out. In response to A’s advances, B said nothing when A removed her clothes, but was clearly too weak to resist. | 0.71 | 0.73 | 0.79 | 0.79 |

| pun5 con5 | A, a supervisor at a large corporation, told B that he would engineer an undeserved promotion for which B had applied if she had sexual relations with him. | 0.70 | 0.70 | 0.62 | 0.67 |

| pun8 con8 | A and B commenced what they thought would be a normal sexual interaction. B unexpectedly found intercourse painful on this occasion, and asked A to stop. A did not withdraw until he ejaculated. | 0.57 | 0.66 | 0.59 | 0.67 |

| pun7 con7 | A was infatuated with B, but B had rebuffed him. A told B that he would commit suicide unless B had sexual relations with him. | 0.54 | 0.48 | 0.75 | 0.67 |

| pun3 con3 | A, whose identical twin was married to B, slipped into B’s bed while she was half asleep. B believed that A was her husband. | 0.54 | 0.53 | 0.68 | 0.70 |

| Fit Indices | Comparative Fit Indices | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| χ2 | df | CFI | RMSEA | BIC | Target | ΔCFI | ΔRMSEA | ΔBIC | |

| M1 | 1483.378 | 144 | 0.905 | 0.091 | 80,025.695 | ||||

| M2 | 1560.954 | 156 | 0.900 | 0.089 | 80,010.646 | M1 | −0.005 | −0.002 | −15.049 |

| M3a | 1747.191 | 168 | 0.888 | 0.091 | 80,104.259 | M2 | −0.012 | 0.002 | 93.613 |

| M3b | 1687.440 | 167 | 0.892 | 0.090 | 80,052.227 | M2 | −0.008 | 0.001 | 41.581 |

| Coefficient | S.E. | z | p | Raw Mean (SD) | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Japan | Canada | |||||

| Perceived appropriateness of punishment | −0.243 | 0.032 | −7.542 | <0.001 ** | 3.73 (0.69) | 3.97 (0.71) |

| Perceived victim’s consent | 0.079 | 0.040 | 1.997 | 0.046 * | 2.21 (0.76) | 2.18 (0.90) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Mukai, T.; Pioch, C.; Sadamura, M.; Tozuka, K.; Fukushima, Y.; Aizawa, I. Comparing Attitudes toward Sexual Consent between Japan and Canada. Sexes 2024, 5, 46-57. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5020004

Mukai T, Pioch C, Sadamura M, Tozuka K, Fukushima Y, Aizawa I. Comparing Attitudes toward Sexual Consent between Japan and Canada. Sexes. 2024; 5(2):46-57. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5020004

Chicago/Turabian StyleMukai, Tomoya, Chantal Pioch, Masahiro Sadamura, Karin Tozuka, Yui Fukushima, and Ikuo Aizawa. 2024. "Comparing Attitudes toward Sexual Consent between Japan and Canada" Sexes 5, no. 2: 46-57. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5020004

APA StyleMukai, T., Pioch, C., Sadamura, M., Tozuka, K., Fukushima, Y., & Aizawa, I. (2024). Comparing Attitudes toward Sexual Consent between Japan and Canada. Sexes, 5(2), 46-57. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes5020004