Abstract

The aim of the article is to determine which countries show the most homophobic attitudes and understand the profile of homophobia in Europe. This article analyses data from the survey “European Values Study” and focuses on three of its questions: “Do you think homosexual people can be good parents”; “the degree of justification of homosexuality”, and “the attitude towards the possibility of having a homosexual neighbour”. For this, we have used a quantitative methodology (mean comparison analysis and multiple correspondences. The sample consists of 56,451 people from 34 European countries. One of the main conclusions is that homophobic attitudes are highest in the eastern countries, former Soviet republics, and, on the contrary, residents in Nordic countries have more inclusive attitudes.

1. Introduction

This article analyses European values towards homosexuality to determine the level of homophobia still present in Europe and enable a classification of European countries on a cultural level. The “homosexuality” variable has been used in previous studies [1,2,3] to measure the degree of tolerance, progressivism and cultural advancement of European societies. The European regions more accepting of homosexuality tend to be more progressive, tolerant societies with higher levels of social capital. However, societies which are less tolerant of homosexuality and display homophobic attitudes tend to be more conservative societies where the influence of religion is greater and the advancement of individual freedoms is more limited.

In this article, we first consider sexual diversity and the incidence of heteronormativity and homophobia from a sociological perspective to delve into the notion of sexuality and its relationship with our cultures. Secondly, we analyse data from the most recent wave of the European Values Study of 2017/2018 in relation to three questions: the extent to which homosexuality is justified, the acceptance of having homosexual neighbours and the ability of homosexuals to be good parents. We have applied the analysis to all European countries that participated in the latest version of the survey to examine if attitudes towards the homosexual population enable us to culturally classify European societies. We can conclude that this is the case: that is, the degree of tolerance towards homosexuality, or conversely, the degree of homophobia, allows us to classify countries. As we found in previous studies where we analysed attitudes towards abortion or euthanasia [4], the main cultural division in Europe occurs between western and eastern Europe and the traditional division between northern and southern Europe is diluted, although it is the Scandinavian Nordic countries that reveal a more open, liberal and normalising culture towards diverse and non-normative sexual behaviour.

Sexual Diversity, Heteronormativity and Homophobia: A Sociological Approach

Sexuality—which comprises elements such as sex, sexual orientation, eroticism, pleasure, intimacy or reproduction—is a central aspect of humans beings which is influenced “by the interaction of biological, psychological, social, economic, political, cultural, ethical, legal, historic, religious and spiritual factors” [5] (p. 3). It is expressed in thoughts, fantasies, desires, practices and intimate relationships, which however, do not alter legitimised social constructs nor elements established by the prevailing social norm. All societies regulate sexual experiences [6] and prescribe the spaces, manner, time and form in which they should take place [7]. Therefore, we can think of sexuality as a social and historical construct “that is configured and reconfigured in specific social contexts and which is expressed through hegemonic cultural discourses that mark positions, generate expectations, create and deny” [8] (p. 98).

According to Andrés [9], in most Western countries, a homosexual is a “person who shares sexual activities, fantasies and desires with another person of the same sex” (p. 122). (However, in certain rural areas of the Maghreb, the term homosexual is applied to married men who have relations with other men (not to unmarried men) and in some rural parts of Mexico, it is applied only to men who allow penetration, which shows that the concept of homosexuality varies in different cultures [9]). Looking back at our past, in western Europe, homosexual relations were forbidden during the middle and modern ages as they challenged the social canon sustained by a religious discourse that associated sexuality with a heterosexual, monogamous and reproductive marriage [10]. From the second half of the 19th century (during this period, the category of homosexual emerged to separate the socially accepted from the abnormal, deviant and dangerous [11]), the stigmatisation of sexual diversity was based on medical science whereby a homosexual person was considered to be sick [9], and any practices not for the purpose of procreation were considered sexual perversions [10]. During the Franco regime, homosexuality was viewed as a disease that was treated with electroshock therapy and repressed as a criminal act (under the Law of Vagrancy and later the Law of Social Danger), which led to many homosexual men being interned in re-education establishments for their reputed rehabilitation [12]. (For Gutiérrez Gallardo [13], the permissiveness towards female homosexuality in comparison to the repression of male homosexuality is rooted in the concept of the passive role of female sexuality centred on male pleasure and its procreative function. That is, Francoist reprisals were harshest towards gay men given the regime could not imagine the existence of lesbians; the same logic was reproduced in Nazism [14]) The American Psychiatric Association and the American Psychological Association did not declassify homosexuality as an illness until 1973 (the depathologisation of homosexuality in 1973 is relative as by being incorporated into the category of dystonic or ego-dystonic sexuality, homosexuality continues to be considered a mental disorder if a person experiences it in a conflictive way, which was difficult to avoid in the homophobic society of the 1970s [15]) [9], whilst the WHO included homosexuality on its list of mental disorders until 1990 [14]. Therefore, from a diachronic perspective, in our context, homosexual people have gradually moved from a position of exclusion—marked by pathologisation, criminalisation or legal discrimination—to one of marginalisation [15] and only recently have their rights as subjects been considered and their life choices legitimised [16]. (After the Netherlands (2000) and Belgium (2003), Spain was the third state to legalise same-sex marriage in 2005 (Law 13/2005, 1 de July). Since then Germany, Austria, Denmark, Slovenia, Estonia, Finland, France, Greece, Ireland, Luxembourg, Malta, Portugal and Sweden have joined the list of European countries that permit homosexual marriage.)

Within the field of study of sexualities [17], Gayle Rubin [18] has theorised that in modern Western societies, there exists a “hierarchical system of sexual value” (p. 136) that hierarchically classifies the following groups: monogamous heterosexual men and women, bound by a monogamous marriage with children; unmarried monogamous heterosexual men and women, with or without offspring, followed by most other heterosexuals; gays and lesbians in stable relationships; promiscuous gays and lesbians and, finally, the most despised sexual castes that includes, transgender people, fetishists, sadomasochists or prostitutes, among others. For Momoitio [13], the notion that underpins this proposal is still current and can be summarised as “there are sexual-affective relationships that are more valued than others” (p. 55). This unequal social worth, imbued with heteronormativity, is reflected in homosexual people’s fear of public displays of affection, in their attempt to hide their sexual orientation in the workplace to avoid problems or in the social aversion towards gays and lesbians looking after young children [14].

Our heteronormative societies have enabled the shaping of oppressed and privileged positions as well as the development of prejudiced attitudes towards homosexual people. According to Pichardo [19], homophobia is “a hostile act towards homosexuality that is expressed in different active forms of physical and verbal abuse, and a silent, institutionalised rejection towards people who identify as homosexuals, limiting their access to rights, spaces, acknowledgement, prestige or power” (p. 146). (Elipe [20] includes in this concept the rejection not only of homosexual people but also of those with an orientation, identity, appearance or gender expression that does not conform with the prevailing heteronormative binary system in society.) There are at least five expressions of homophobia: cognitive (thinking that homosexuality is unnatural, that it is a sin and that homosexual people should not have the same rights as other people); affective (feelings of rejection, fear or disgust towards these people); behavioural (active exclusion and rejection); liberal (of the opinion that public space should be heterosexual and free from homosexual displays of affection, understood as provocative or lacking respect) (in this sense, Denney [21] notes that stating that “it’s your private life and it doesn’t concern me or anyone else” is an extremely insidious tactic that in practice comes down to “we’re going to behave like straight men and what you do in the bedroom is your business” (p. 67)); and lastly, institutional, when discrimination towards this group forms part of the structural framework—state, educational, healthcare, corporate—and its everyday operation [22].

The negative appraisals that characterise prejudice can arise from stereotypes, which are defined as beliefs about the personal attributes of a group of people and can be generalisations, overgeneralisations, or misconceptions [23]. Some stereotypes of gay people characterise them as sensitive, sex-obsessed, narcissists, unable to commit and affluent. Conversely, lesbianism is attributed to bad sexual experiences with men who have treated them badly or ignore them due to their physical appearance [14]. There is not such an established image of lesbians, although the effect of not having such a marked stereotype is the erasure of this group [10].

According to Quiles et al. [24], currently, the normative pressures in favour of equality and tolerance—and the tendency for people to present themselves as unprejudiced individuals—among other factors, have created a context in which favourable social attitudes towards homosexual people coexist alongside discrimination towards this group, and in which homophobia is not always explicitly expressed but can be perceived in subtle or covert ways. Further, negative social views of homosexual people can also be assimilated in one’s self-concept [25], generating an internalised homophobia which can lead to difficulties in accepting one’s own sexual orientation—rejecting or hiding it—which can have important consequences on one’s health and well-being [25,26].

For Coll-Planas [15], “the cause of the aversion towards gays and lesbians is that, by breaking the rules of man/woman complementarity, they change the rules of gender” (p. 101). Homophobia, therefore, has an instrumental character that is related to sustaining the gender binary model and “the heterosexual matrix” [27]. It is also the main mechanism for controlling masculinity, as in many societies, being “masculine” implies rejecting homosexuality (Connell [28] consistently points out that society defines homosexual masculinity as the opposite of an authentic man and that homosexual masculinity, which occupies the lower end of masculinities in the gender order, presents discarded traits of hegemonic masculinity), which according to Pichardo [22], underpins the fact that men tend to demonstrate proportionally greater homophobic attitudes than women.

In this context, for queer theory, far from being considered as a repressed field, sexuality can be conceived as a sphere with subversive and transformative potential [29]. From this perspective, male and female homosexuality as “abject” or “dissident” or “pertaining to the margins” [30] (p. 18) questions the gender binaries and compulsory heterosexuality [31] that run through it, rejecting all discourse that escapes that logic [32]. However, from an intersectional perspective, it is worth remembering that “not all gays or all lesbians share the same individual or collective concerns” [33] (p. 40) and that “nor do all non-normative sexualities lack privilege or access to some elements of privilege and power”; thus, they do not necessarily share the same place of transgression [30] (p. 19).

The following sections immerse us in the imaginary of the European population and, in this field of meanings, allow us to explore the “symbolic spaces of exclusion” [34] (p. 125) or subversion linked to the close social interaction of parenthood of homosexual people.

2. Methodological Framework

2.1. Participants and Sample

The total sample size is N = 56,491. This sample was obtained with the participation of the 34 European countries presented below.

The total sample has been obtained from the sum of the samples of each country, all of them being representative with samples of more than 1000 people, as can be seen. All countries are considered in the same way, regardless of their size, since the complete sample is already weighted by the EVS methodological team, making it a representative sample for each country. The final total sample is weighted, according to the size of each country, by the EVS methodological team.

The total sample is represented by 55.3% of women and 44.7% of men. In terms of age, 24.3% are between 16 and 34 years old; 33.6% are between 35 and 54 years old; and 42% are over 55 years old. Among the respondents, 64.5% consider themselves as a religious person; 27.6% as a non-religious person; and 7.9% as a convinced atheist

The best recommended strategy for randomisation has been to use census data with the aim of assuring that all individuals on the list have an equal chance of being selected.

The definition of the paths, the procedure for selecting the building, building number, floor, apartment number, and person to interview was also entirely established and agreed between the researchers and principal researchers (PIs) of each country and the methodological team of the European Values Study [35].

The fieldwork was carried out between December 2017 and January 2018.

2.2. Data Analysis

Being a descriptive study, we have analysed the data in terms of percentages of agreement–disagreement with the variable that we are trying to measure, which is “Homosexual couples are as good parents as other couples”. In addition, we have used contingency tables to analyse the association between the variable “country” and the agreement or not with the sentence mentioned above. We have also carried out a correspondence analysis to see the relationship between the “country” and the position of acceptance of parenthood in same-sex couples. Correspondence analysis allows us to examine the relationship between two variables graphically in a multidimensional space by calculating row and column scores. Categories that are similar to each other appear close to each other on the graph. In this case, the figure shows how each country is positioned in terms of greater or lesser support for homosexual couples as parents.

We have also considered the positioning of the population on a scale of never (1)/always (10) for the item “Can homosexuality be justified?” (The item on whether homosexuality can be justified is part of a question in the European Values Study questionnaire that also includes the degree of justification of other behaviours such as abortion or euthanasia as well as acts such as not paying taxes or driving under the influence of alcohol. It is a question that tries to measure whether respondents justify, authorise or condone such behaviours.) In order to analyse this item, we have carried out a comparison of means (Anova) between the 34 countries in relation to the justification of homosexuality.

Finally, we have considered the question “would like to have homosexuals as neighbours”. This question is dichotomous with two possible answers: yes or no. We have analysed it in terms of percentages using a contingency table according to the country.

By analysing these three questions that appear in the survey in relation to the homosexuality, we can estimate some attitudes of the European population towards homosexuality and measure the levels of tolerance of the various countries on this issue. The divisions between northern, southern, eastern and western Europe, also considering the existence of central Europe, is not only a geographical but also a political and historical classification. The classification is based on the typologies of welfare states developed by Gösta Esping-Andersen based on economic variables (social spending) but also on social impact (decommodification and social stratification) and ideological variables (capitalist and communist or ex-communist systems). In this sense, northern Europe is made up of Scandinavian countries such as Norway, Sweden, and Finland, and the east is represented by Russia and all the ex-communist republics.

The analysis of these 3 items allows access to specific factors indicating levels of homophobia/tolerance It is impossible to collect all attitudes, but it is feasible to carry out a comparative descriptive analysis that provides relevant information about the different cultures in Europe.

The analysis was carried out using SPSS (version 28).

3. Results

In Table 1, we can see that the level of disagreement with the statement that homosexual couples can be as good parents as other couples is higher than the level of agreement. More than 42% of the European population surveyed disagreed with the statement compared with 34.4% who agreed.

Table 1.

Participant countries in the sample.

The persistence of homophobic thought that continues to undervalue the parenthood rights of homosexual couples is striking. This thinking is explicitly shown with 23% of respondents strongly disagreeing and 19% disagreeing with the statement. It is also implicitly shown in the high 16% that neither agree nor disagree with the statement and 7.7% of people who do not know.

If we focus on the European countries in relation to this statement (Table 2), we can see large differences between countries. Some countries position themselves very much in agreement with the suitability of same-sex couples as parents, whilst in other countries, there is an absolute intolerance towards this family model. Thus, support for the suitability of same-sex parenthood varies greatly along north–south/east–west axes.

Table 2.

Degree of agreement with the statement “homosexual couples are as good parents as other couples”. Percentages for Europe (%).

As the table shows (Table 3), support is particularly high in Nordic countries. For example, percentages of agreement in Iceland, Sweden and Norway exceed 70%, while the transcontinental countries of Azerbaijan, Georgia and Armenia, together with Serbia, are at the opposite extreme, with levels of support that do not reach 6%, which shows very low tolerance for options that deviate from traditional and normative family models.

Table 3.

Degree of agreement with the statement “homosexual couples are as good parents as other cou-ples”. Horizontal percentages by country (%).

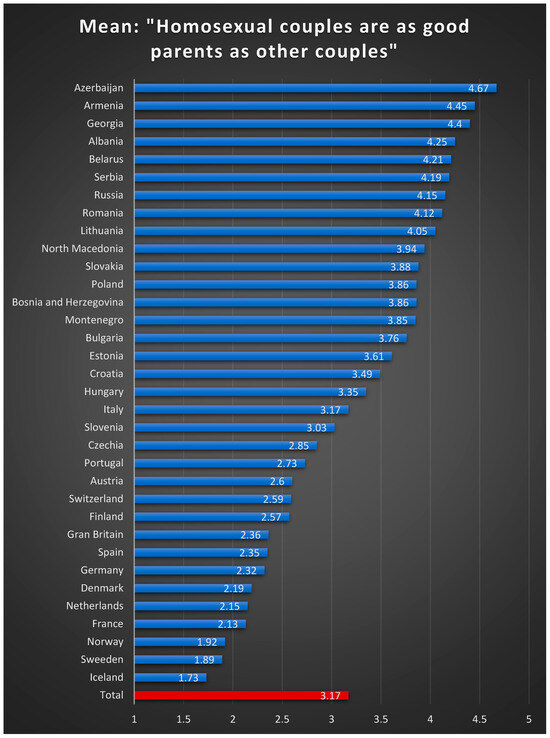

If we look at the mean values for each country (Figure 1) for the statement that same-sex couples are as good parents as other couples (1 being strongly agree and 5 being strongly disagree), countries with higher means are those that show a stronger level of disagreement with the statement. Those countries with lower means are more in agreement with the statement. The European average is 3.17, which tends more towards disagreement.

Figure 1.

Mean score on a scale of 1 (strongly agree) to 5 (strongly disagree) in relation to the degree of agreement that same-sex couples are good parents. Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the European Values Study [35].

At one end of the scale, we find countries with average disagreement scores higher than 4. Those countries with the highest level of disagreement are Azerbaijan, Armenia and Georgia, followed by Belarus, Serbia, Russia, Romania and Lithuania. These countries are well above the European average of 3.17.

At the other end of the scale, we find the countries that agree the most with the statement. Some Nordic countries such as Iceland, Norway and Sweden have scores below 2, which is followed by France and other northern European countries such as the Netherlands and Denmark. Countries such as Germany, Spain and Great Britain are below the average and thus show a favourable attitude towards the parenting abilities of same-sex couples. It is noteworthy that only 9 countries of the 34 that were surveyed score below 2.5 on this 1–5 scale.

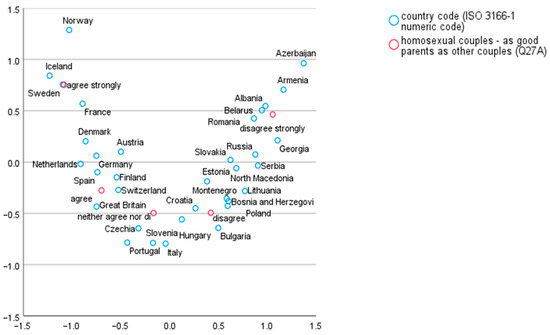

In Figure 2, we show the relationship between country and the agreement or disagreement with homosexual couples as parents. The diagram shows how each country is positioned in terms of more or less agreement. Correspondence analysis clearly shows (Figure 2) the positioning of different countries. Eastern European countries have a higher level of disagreement, as they are located in the upper right quadrant and clustered around the “strongly disagree” option. In the upper left quadrant, clustered around the “strongly agree” option, we find northern European countries such as Iceland, Norway and Sweden.

Figure 2.

Distribution of European countries in respect of the degree of agreement or disagreement with the statement “Homosexual couples are as good parents as other couples?”. Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the European Values Study [35].

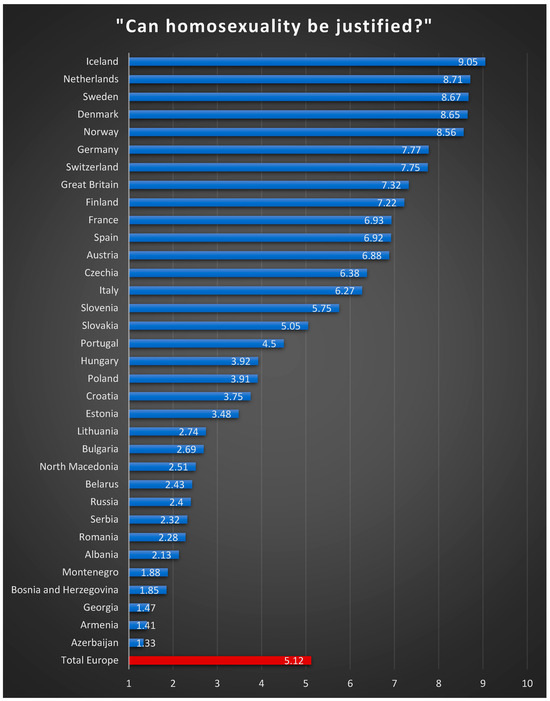

In relation to the second item (Figure 3), which refers to the justification of homosexuality, the European average is 5.12 on a scale of 1 (never) to 10 (always) which seems to indicate that the European position reflects a central average which is the result of diverse country positions on the scale. In this case, 16 countries have a score above 5. However, we cannot ignore the fact that 18 countries have a score below 5, which could suggest an intolerance towards homosexual people. In other words, these countries situate themselves more towards the position of never justifying this sexual orientation.

Figure 3.

Can homosexuality be justified? Mean scores on a scale of 1 (never) to 10 (always) in relation to the degree of justification for homosexuality. Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the European Values Study [35].

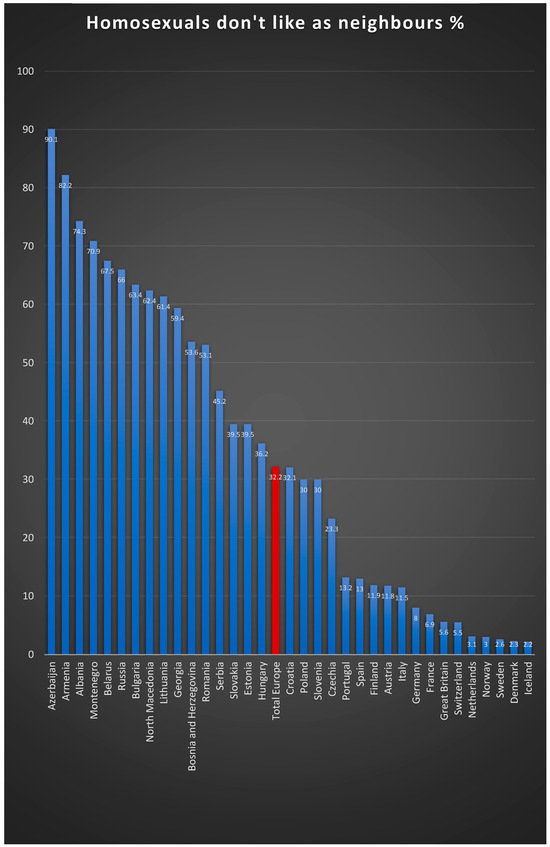

With respect to having homosexuals people as neighbours (Figure 4), in general, it seems that this is more accepted than the previous two items. Thus, less than half of the European population, namely one third (32.2%), state that they would not like to have a homosexual neighbour. The extreme positions are repeated here also with Azerbaijan and Iceland holding completely opposing positions. In Iceland, only 2.2% of the population would not want homosexual people as neighbours, whereas in Azerbaijan, this percentage increases to almost the entire population (90.1%).

Figure 4.

Percentage (%) of people that do not want homosexuals people as neighbours. Source: Authors’ construction based on data from the European Values Study [35].

4. Discussion

The main objective of our study is to determine which countries show the most homophobic attitudes and understand the profile of homophobia in Europe. Let us recall that greater or lesser homophobia has also been related to more progressive values and more inclusive social models. The analysis of the three questions analysed from the European Values Study questionnaire: ‘Do you think homosexual people can be good parents’; ‘the degree of justification of homosexuality’, and ‘the attitude towards the possibility of having a homosexual neighbour’ clearly shows us that in all cases, the most reactionary attitudes and homophobia are registered in eastern European countries, while the most favourable and positive attitudes are obtained in the Nordic countries.

We have seen that the Nordic societies show more equitable, tolerant and diversity-inclusive values. All these countries are societies that have egalitarian social stratification, low levels of poverty and social exclusion, and more tolerant attitudes towards diversity It is also worth highlighting a group of countries that demonstrate progressive values and do not question homosexual people as potential neighbours: namely, France, Germany, Italy, Austria, Spain and Portugal. This indicates a blurring of the traditional north–south divide, as southern European countries increasingly resemble central European countries on matters such as those analysed, demonstrating the loss of power and influence of the Catholic Church as a consequence of the process of secularization [36].

The majority of countries that show homophobic attitudes are former Soviet Republics, in which the fall of communism signified the beginning of a certain religious fundamentalism or, at least, a greater orthodoxy of religious experience. This, undoubtedly, has a bearing on a greater rejection of behaviours that question normativity, the classic sexual division and, above all, traditional masculinity [3,37].

When we analyse attitudes and values relating to sexuality, the traditional divide between northern and southern European countries, explained by the influence of Catholicism in southern Europe, seems to have been diluted. It is possible that the incidence of processes such as secularisation [36,38] and individualisation [39] explain the evolution of values in countries such as Spain, Portugal or Italy where there is no homophobic majority and the scores and percentages are very similar to those recorded in central European countries such as France, Germany, Austria or the Netherlands.

The countries hold similar positions on the three questions analysed, and there is a clear difference between western and eastern Europe when it comes to justifying homosexuality. The former always justify it while the latter would never do so. It also appears that same-sex parenthood represents a family model that, in a large part of Europe, does not yet appear to be normalised, as homosexual couples are not considered to be as good parents when compared to heterosexual couples. Only eleven countries score below 2.5, and these are again the Nordic countries, some central European countries such as Germany, Denmark and France, and one country from the south, Spain, which scores as one of the most progressive countries when it comes to attitudes towards homosexuality.

Without doubt, attitudes towards homosexuality provide a clear indication of the degree to which progressive values that accept social and identity diversity without prejudice have advanced [2]. Studies of values centred in European regions, rather than states, are interesting as they reveal interesting differences and similarities between regions that, in some cases, transcend states’ political borders. We have a clear example in the Autonomous Community of the Basque Country in Spain; it is one of the European regions with the highest level of justification of homosexuality with a score above 9, putting it on a more of a par with Nordic countries than with other Spanish regions [40].

5. Conclusions

Analysis of the three questions from the European Values Study related to homosexuality uncovers significant levels of homophobia in Europe. All three questions reveal a rejection of homosexuality with differing degrees of intensity. The most widespread rejection is the notion that homosexual people cannot be as good parents as heterosexual people. On a second level, we have the degree of justification of homosexuality as a behaviour, which also shows a significant rejection from a considerable number of countries with 18 of the 34 countries analysed at levels below 5 on a scale of 1 (never justified) to 10 (always justified). Finally, attitudes improve somewhat when asked about their willingness to have a homosexual person as a neighbour, although 30% would reject a homosexual neighbour.

There is a division in Europe between the west and the east. The former Soviet Republics display an evident homophobia and a strong rejection of homosexuality. This issue is not found in the majority of western Europe, where the Scandinavian countries stand out as having inclusive, egalitarian values without homophobic prejudices. In summary, homophobic attitudes and very low tolerance levels towards sexual diversity still persist in large parts of Europe in the 21st century.

We end the section on conclusions by mentioning the limitations of our study and mentioning future research lines and questions that may arise from it. We consider that the main limitation of our work lies in the fact that we have to base our interpretations on questions that we have not defined, since they belong to a previously existing questionnaire. This ensures the comparability and international scope of the results, but it limits the depth of our research on attitudes towards homosexuality. Undoubtedly, it is clear that future qualitative analyses will make it possible to go deeper into the homophobic attitudes detected in some countries and socio-demographic profiles.

As a result of our work, new research questions arise that have to do with how homophobic attitudes are constructed, what relationship they have with the construction of non-normative identities, the impact of different religions or how certain stereotypes and prejudices about the sexual life of homosexual people function when homosexuality is rejected. It would also be interesting to delve into the relationship between the different legislative frameworks and the greater or lesser justification of homosexuality.

Author Contributions

Each author agrees to be personally accountable for the author’s own contributions and for ensuring that questions related to the accuracy or integrity of any part of the work, even ones in which the author was not personally involved, are appropriately investigated, resolved, and documented in the literature. Provision of individual contributions: Conceptualisation, R.R.P. and M.S.C.; Methodology, I.A.F.; Software, I.A.F.; Validation, I.A.F., R.R.P. and M.S.C.; Formal Analysis, I.A.F.; Investigation, M.S.C., I.A.F. and R.R.P.; Resources, I.A.F.; Data Curation, I.A.F.; Writing—Original Draft Preparation, M.S.C., R.R.P. and I.A.F.; Writing—Review and Editing, M.S.C., R.R.P. and I.A.F.; Visualisation, M.S.C.; Supervision, M.S.C.; Project Administration, M.S.C.; Funding Acquisition, M.S.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Basque Government. Call for Recognition of Research Teams. Grant number [IT1596-22].

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results can be found: https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/ (accessed on 7 March 2024).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Slootmaeckers, K.; O’Dwyer, C. Europeanization of attitudes towards homosexuality: Exploring the role of education in the transnational diffusion of values. Innovation 2018, 31, 406–428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuntz, A.; Davidov, E.; Schwartz, S.H.; Schmidt, P. Human values, legal regulation, and approval of homosexuality in Europe: A crosscountry comparison. Eur. J. Soc. Psychol. 2015, 45, 120–134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäckle, S.; Wenzelburger, G. Religion, Religiosity, and the Attitudes Toward Homosexuality—A Multilevel Analysis of 79 Countries. J. Homosex. 2015, 62, 207–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvestre Cabrera, M.; Aristegui Fradua, I.; Beloki Marañón, U. Abortion and euthanasia: Explanatory factors of an association in Thanatos. Analysis of the European Values Study. Front. Political Sci. 2022, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. La Salud Sexual y su Relación con la Salud Reproductiva. Un Enfoque Operativo [Sexual Health and Its Linkages to Reproductive Health. An Operational Approach]. Available online: https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/274656/9789243512884-spa.pdf (accessed on 18 March 2024).

- Plummer, K. La diversidad sexual: Una perspectiva sociológica [Sexual diversity: A sociological perspective]. In La Sexualidad en la Sociedad Contemporánea. Lecturas Antropológicas [Sexuality in Contemporary Society. Anthropological Readings]; Nieto, J.A., Ed.; Fundación Universidad-Empresa: Madrid, Spain, 1991; pp. 151–193. [Google Scholar]

- Guasch, Ó. Para una sociología de la sexualidad [Towards a sociology of sexuality]. Reis 1993, 64, 105–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frinco, V. Sexualidad, género y educación sexual [Sexuality, gender and sex education]. Extramur. Rev. Univ. Metrop. Cienc. Educ. 2018, 17, 97–107. [Google Scholar]

- Andrés, R. La homosexualidad masculina, el espacio cultural entre masculinidad y feminidad, y preguntas ante una crisis [Male homosexuality, the cultural space between masculinity and femininity and questions in the face of a crisis]. In Nuevas Masculinidades [New Masculinities]; Segarra, M., Carabí, A., Eds.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2000; pp. 121–150. [Google Scholar]

- Sanvicéns, L.A. Jóvenes, Diversidad y Homofobia [Youth, Diversity and Homophobia]. 2023. Available online: https://info.lojoven.es/wp-content/uploads/2023/02/diversidad.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2024).

- Preciado, B. Manifiesto Contrasexual [Counter-Sexual Manifest]; Editorial Anagrama: Barcelona, Spain, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Coll-Planas, G.; Vidal, M. Dibujando el Género [Drawing Gender]; Editorial Egales: Barcelona/Madrid, Spain, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez Gallardo, R. Protección penal de la identidad sexual y lucha contra la homofobia [Criminal protection of sexual identity and the fight against homophobia]. In Políticas Públicas en Defensa de la Inclusión, la Diversidad y el Género [Public Politics in Defence of Inclusion, Diversity and Gender]; Guzmán, R., Librero, A.B., Gorjón, M.C., Eds.; Universidad de Salamanca: Salamanca, Spain, 2020; pp. 1219–1224. [Google Scholar]

- Momoitio, A. Lesbianismo y otras proezas [Lesbianism and other exploits]. In Feminismos. Miradas Desde la Diversidad [Feminisms. Perspectives from Diversity]; Fernández, J., Ed.; Ediciones Oberon: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 29–41. [Google Scholar]

- Coll-Planas, G. La Voluntad y el Deseo. La Construcción Social del Género y la Sexualidad: El Caso de Las Lesbianas, Gays y Trans [Will and Desire. The Social Construction of Gender and Sexuality: The Case of Lesbians, Gays and Trans]; Editorial Egales: Barcelona/Madrid, Spain, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, J.I. Entender la Diversidad Familiar: Relaciones Homosexuales y Nuevos Modelos de Familia [Understanding Family Diversity. Homosexual Relationships and New Family Models]; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maquieira, V. Género, diferencia y desigualdad [Gender, difference and ineequality]. In Feminismos. Debates Teóricos Contemporáneos [Feminisms. Contemporary Theoretical Debates]; Beltrán, E., Maquieira, V., Eds.; Alianza: Madrid, Spain, 2001; pp. 127–184. [Google Scholar]

- Rubin, G. Reflexionando sobre el sexo: Notas para una teoría radical de la sexualidad [Thinking sex: Notes for a radical theory of the politics of sexuality]. In Placer y Peligro: Explorando la Sexualidad Femenina [Pleasure and Danger: Exploring Female Sexuality]; Vance, C.S., Ed.; Revolución: Madrid, Spain, 1989; pp. 113–190. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, J.I. Homosexualidad y familia: Cambios y continuidades al inicio del tercer milenio [Homosexuality and family: Change and continuity at the beginning of the third millenium]. Política Y Soc. 2009, 46, 143–160. [Google Scholar]

- Elipe, P. Acoso LGBTQ+fóbico [LGBTQ+phobic bullying]. In Prevención de la Violencia Interpersonal en la Infancia y la Adolescencia [Prevention of Domestic Violence in Childhood and Adolescence]; Sánchez, V., Ed.; Pirámide: Madrid, Spain, 2019; pp. 117–140. [Google Scholar]

- Denney, M. Política gay: Dieciséis propuestas [Gay politics: Sixteen proposals]. In Manifiestos Gays, Lesbianos y Queer [Gay, Lesbian and Queer Manifestos]; Mérida, R.M., Ed.; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; pp. 165–189. [Google Scholar]

- Pichardo, J.I.; De Stéfano, M.; Faure, J.; Sáenz, M.; Williams, J. Abrazar la Diversidad: Propuestas Para una Educación Libre de Acoso Homofóbico y Transfóbico [Embracing Diversity: Proposals for an Education Free from Homophobia and Transphobia]. Available online: https://www.inmujeres.gob.es/actualidad/NovedadesNuevas/docs/2015/Abrazar_la_diversidad.pdf (accessed on 14 February 2024).

- Myers, D.G. Exploraciones de la Psicología Social [Social Psychology]; Mc Graw Hill: Madrid, Spain, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Quiles, M.N.; Betancor, V.; Rodríguez, R.; Rodríguez, A.; Coello, E. La medida de la homofobia manifiesta y sutil [The measure of overt and subtle homophobia]. Psicothema 2003, 15, 197–204. [Google Scholar]

- Herek, G.M.; Gillis, J.R.; Cogan, J.C. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: Insights from a social psychological perspective. J. Couns. Psychol. 2009, 56, 32–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Legate, N.; Weinstein, N.; William, S.R.; DeHaan, C.R. Parental autonomy support predicts lower internalized homophobia and better psychological health indirectly through lower shame in lesbian, gay and bisexual adults. Stigma Health 2018, 4, 367–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, J. Cuerpos Que Importan. Sobre Los Límites Discursivos Del “Sexo” [Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of “Sex”]; Editorial Planeta: Barcelona, Spain, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Connell, R. Masculinities; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suárez, M. Discursos de Sexualidad y Poder. Continuidades y Rupturas del Orden Sexual Heteropatriarcal [Discourses of Sexuality and Power. Continuities and Ruptures of the Heteropatriarchal Sexual Order. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidad de Deusto, Bilbao, Spain, 27 September 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Platero, R. Intersecciones: Cuerpos y Sexualidades en la Encrucijada [Intersections: Bodies and Sexualites at the Crossroad]; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Rich, A. La heterosexualidad obligatoria y la existencia lesbiana lesbiana [Compulsory heterosexuality and lesbian existence]. In Sexualidades, Género y Roles Sexuales [Sexuality, Gender and Sexual Roles]; Navarro, M., Stimpson, C., Eds.; Fondo de Cultura Económica: Buenos Aires, Argentina, 1999; pp. 159–212. [Google Scholar]

- Wittig, M. El pensamiento heterosexual (1978–1980) [Heterosexual thought (1978–1980)]. In Manifiestos Gays, Lesbianos y Queer. Testimonios de Una Lucha (1969–1994) [Gay, Lesbian and Queer Manifestos. Testimonios of a Struggle (1969–1994)]; Mérida, R.M., Ed.; Icaria Editorial: Barcelona, Spain, 2009; pp. 133–143. [Google Scholar]

- Mérida, R.M. (Ed.) Manifiestos Gays, Lesbianos y Queer. Testimonios de Una Lucha (1969–1994) [Gay, Lesbian and Queer Manifestos. Testimonios of a Struggle (1969–1994)]; Icaria: Barcelona, Spain, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Guzmán, P.; Platero, R. Passing, enmascaramiento y estrategias identitarias: Diversidades funcionales y sexualidades no-normativas [Passing, masking and identity strategies: Functional diversities and non-normative sexualities]. In Intersecciones: Cuerpos y Sexualidades en la Encrucijada Encrucijada [Intersections: Bodies and Sexualites at the Crossroad]; Platero, R.L., Ed.; Edicions Bellaterra: Barcelona, Spain, 2012; pp. 125–158. [Google Scholar]

- European Values Study (EVS). Methodology EVS. 2017. Available online: https://europeanvaluesstudy.eu/methodology-data-documentation/survey-2017/methodology/ (accessed on 22 March 2024).

- Halman, L.; Van Ingen, E. Secularization and Changing Moral Views: European Trends in Church Attendance and Views on Homosexuality, Divorce, Abortion, and Euthanasia. Eur. Sociol. Rev. 2015, 31, 616–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wawrzonek, M.; Bekus-Gonczarowa, N.; Korzeniewska-Wiszniewska, M. Orthodoxy Versus Post-Communism?: Belarus, Serbia, Ukraine and the Russkiy Mir; Cambridge Scholars Publishing: Newcastle upon Tyne, UK, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Finke, R.; Adamczyk, A. Cross-national Moral Beliefs: The Influence of National Religious Context. Sociol. Q. 2008, 49, 617–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beck, U.; Beck-Gernsheim, E. Individualization. In Institutionalized Individualism and Its Social and Political Consequences; Sage Publications: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Silvestre Cabrera, M. (Ed.) Valores Para una Pandemia. La Fuerza de Los Vínculos. Quinta Encuesta Europea de Valores en su Aplicación a Euskadi, [Values for a Pandemic. The Strength of Bonds. Fifth European Values Survey in Its Application to the Basque Country]; Síntesis: Madrid, Spain, 2001. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).