1. Introduction

Self-concept is an important psychological construct with roots in the early days of psychology [

1]. Self-concept and identity are integrally related; how one views oneself can lead one to adopt a label or identity that describes the self (e.g., “I am a …”). Self-concept is thought to have many different dimensions (e.g., self-esteem, values, traits, likes and dislikes) and apply to many life domains (e.g., academic, artistic, athletic, mental health, romantic partner/relational). Self-concept is thought to be composed of the salient and important identities used to define one’s self [

2]. One specific self-concept area emerging within the field involves sexuality. However, theorizing and research regarding sexual identity and its development have often focused on sexual orientation minority groups [

3,

4,

5]. Another aspect of self-concept are self-feelings and self-image, which include sensory or bodily feelings [

2]. This sensory self-concept component may be sexually-oriented, such as how one feels about their own sexuality and sexuality in general. Thus, one’s sexual self-concept is “who I am as a sexual person”.

Some researchers have investigated this construct in relation to concept measurement [

6,

7,

8], while others look at the relationship with relevant outcome variables such as sexual risk-taking or sexual health [

9,

10,

11]. Deutsch et al. [

6] and Potki, Ziaei, Faramarzi, Moosazadeh, and Shahhoseini [

12] pointed out that there are several models existing that describe components of sexual self-concept. Common sexual self-concept components include self-esteem or one’s sense of worth; self-efficacy, which might also be defined as sexual competency or agency; negative affect around sexuality, particularly sexual anxiety; motivation, which may include arousal, desire, or acknowledgment of sex drive; and openness or responsiveness to sexuality.

Potki et al. [

12], in particular, reviewed factors thought to affect the sexual self-concept. They acknowledged that sexual self-concept is a dynamic construct, influenced by and influencing sexual experiences, attitudes, interpretations, and so forth. Potki et al. [

12] concluded that numerous individual differences (e.g., age; gender; race; or relationship, disability, or STI status), psychological components (e.g., body image issues, sexual violence/abuse history, mental health status), and social constructs (e.g., family, peer relations, media) can affect the construction, content, and strength of the sexual self-concept. While many models include common sexual self-concept constructs, these biopsychosocial factors could have a differential impact on the content and strength of the sexual self-concept based on the characteristics of the individuals being assessed; for example, Biney [

13] argued for culturally-specific scales when addressing sexual self-concept in a sample of sub-Saharan African adolescents from an urban setting. Hensel, Fortenberry, O’Sullivan, and Orr [

14] conducted a longitudinal analysis of adolescent girls’ sexual self-concept and sexual behavior; they concluded that the sexual self-concept develops and changes over time, both influenced by and influencing sexual experience (experience was primarily defined as penis-in-vagina intercourse). What is missing from these works is the treatment of the process by which one’s sexual self-concept develops.

We posit that sexual self-concept, or one’s sexual selfhood, might be thought of as being undergirded by global sexual identity. Identity has been defined as “… a coherent sense of one’s [sexual] values, beliefs, and roles” [

15] (p. 22), while sexual self-concept has been called “… an understanding of one’s self as a sexual person” [

14] (p. 675). Thus, sexual identity could be thought of as leading to sexual self-concept. Regardless, what appears to be missing from the sexual self-concept literature is a treatment of how the sexual self-concept arises. Sexual self-concept, a function of sexual identity (or identities), likely flows from a developmental process.

Worthington and others [

5,

15,

16] addressed the process of sexual identity development as a universal phenomenon—creating a model that applies regardless of sexual orientation. Thus, they conceptualized sexual identity as a more global construct—beyond the vernacular meaning of sexual identity as a sexual orientation social identity label [

17]. Dillon et al. [

16] stated that sexual identity involves many areas of human sexuality such as needs, wants, preferences, values, partner characteristics, and modes of expression, in addition to the social identity of one’s particular sexual orientation label. Understanding these domains of one’s sexual identity likely gives rise to beliefs, thoughts, and knowledge of the sexual self, that is, sexual self-concept.

How does one gain this knowledge? Worthington and colleagues [

5] applied Marcia’s [

18] identity statuses theory to sexuality. In short, Marcia’s theory, arising out of Erikson’s ego-development theory, suggests that an identity status (i.e., achieved, moratorium, foreclosed, and diffused) is a function of two processes: exploration and commitment. Exploration is defined as examining, considering, reflecting upon, or investigating a particular issue (e.g., what do I like sexually?). Commitment entails embracing, investing in, or accepting a particular concept as relevant to the self. For example, a person who has explored a sexuality area, such as preferred sexual activities, and has committed to the construct is said to have an achieved identity status (e.g., “I am an out, loud, and proud kinkster”). As a result of this theoretical application to sexuality, Worthington et al. [

15] created a measure to assess this sexual identity development process (with sexual identity being robust and including sexual needs, expressions, preferences, etc., beyond orientation).

Another important aspect of the sexual self involves one’s feelings of ease or comfort with sexuality. Erotophobia–erotophilia was first conceptualized as an individual difference by Fisher, Byrne, White, and Kelley [

19], and is thought to be a learned affective and evaluative response to sexual content. Discomfort or negativity toward sexuality is conceptualized as erotophobia, while the opposite would be erotophilia. One’s comfort with sexuality influences much of one’s sexual life. Erotophobia–erotophilia might be thought of as part of one’s sexual personality and may influence sexuality-related behaviors, feelings, cognitions, and perceptions of sexual needs, preferences, expression, values, and other sexual identity components. It may be the feeling or affective component of the sexual self.

Erotophobia–erotophilia could also be influenced by the sexual identity development process. For example, those who are exploring their sexual identity, while acquiring knowledge of and developing their sexual self-concept, are likely to enhance their comfort or discomfort with sexual topics, ideas, concepts, and so forth. Conversely, erotophobia–erotophilia could influence the sexual identity development process. If a person is erotophobic and finds sexuality repugnant, they might be more likely to foreclose on their sexual identity development process. However, given that Fisher et al. [

19] theorized that erotophobia–erotophilia is a learned disposition, the most logical direction would appear to be that the process of learning about sexuality in the pursuit of development of sexual identity shapes or reinforces erotophobia–erotophilia.

Study Objectives. The goal of the current study was to investigate the relationship between sexual identity development and sexual self-concept. Theoretically, we have argued that the process of sexual identity development is likely a determinant of sexual self-concept; however, this can only be assessed by a longitudinal lifespan study. Instead, as an initial step, we assessed the relationship between sexual identity development (operationalized by Worthington et al.’s [

15] sexual identity development process instrument) and sexual self-concept (measured by some of Snell’s [

8] sexual self-concept instruments). Furthermore, we included erotophobia–erotophilia as a companion construct with sexual self-concept and investigated its relationships with sexual identity development and sexual self-concept. In the current study, erotophobia–erotophilia was assessed using Tromovitch’s [

20] measure of comfort with sexuality. Specifically, we expected that people who have engaged in greater identity exploration, who express greater sexual identity commitment, who have greater integration of their sexual identity, and who have low levels of sexual orientation uncertainty would have a more positive sexual self-concept and would be more erotophilic.

3. Results

Table 1 presents the zero-order correlations of the sexual identity development, sexual self-concept, and the comfort with sexuality variables. Most of the zero-order correlations were weak (0.20 to 0.30) to moderately strong (0.40 to 0.50) and most were significant due to the large sample size. If single measures of sexual identity development, sexual self-concept, and erotophobia–erotophilia were used, then three Pearson

r correlations would be calculated to address the research questions. However, the three hypothetical constructs in this study were thought to be multi-dimensional in nature. Measurement of these latent constructs was represented by multiple scales; consequently, path analysis by way of canonical correlation analysis—a form of general linear modeling—was used to produce multivariate correlations (

Rc) representing the relationships between the three sets of variables under study. This relationship (

Rc) is derived from a set of equations, called canonical functions or canonical variates. In a canonical correlation analysis, there are as many equations or canonical functions (also called canonical roots) as there are variables in the smallest set of construct indicators. For example, the relation between sexual identity development and sexual self-concept will have four functions because sexual identity development is represented by four MoSIEC variables. These functions are a means of understanding the nature of the relationship between the two latent constructs, combining the variables such that the relationship between the two sets is maximized. In essence, canonical correlation is similar to multiple regression analysis except that canonical correlation is used when there are multiple outcome measures versus one outcome measure (see Sherry & Henson [

28] for a description of canonical correlation). Canonical correlation, a first generation general linear procedure, was adopted over second generation structural equation modeling because canonical correlation is oriented more toward exploratory relationship analysis, whereas SEM is used for model testing [

29].

3.1. Canonical Correlation between Sexual Identity Development and Sexual Self-Concept

A canonical correlation analysis was conducted using the four sexual identity development variables as correlates of the 11 sexual self-concept scales in order to evaluate the shared relationships between the two conceptual variables (i.e., sexual identity development, as represented by the set of four MoSIEC sexual identity development variables [

15], and sexual self-concept, represented by the 11 Snell scales [

8,

24]). The analysis produced four functions (function

Rc2s = 0.52, 0.15, 0.10, and 0.04, respectively). The full model was significant (Multivariate

F (44, 1108) = 7.94,

p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.35) with 65% of the variance shared between the two variable sets (i.e., sexual identity development and sexual self-concept;

Rc = 0.81).

Dimension reduction allows for examination of the relationship at a deeper (function) level. That is, we can consider why sexual identity development and sexual self-concept might correlate Rc = 0.81 by examining the functions underlying the correlation; this can aid in the understanding of what is driving the overarching correlation between the two latent constructs. The functions are based on different, orthogonal combinations of the variables within the two correlated constructs (i.e., sexual identity development and sexual self-concept) and produce a function-specific correlation between the latent constructs. The functions, that is, the combination of individual variables within each set, might be thought of as similar to factors in principle component analysis. Three of the four functions were statistically significant (Function 1 to 4 F (44, 1108) = 7.94, p < 0.0001; Function 2 to 4 F (30, 852) = 3.18, p < 0.0001; and Function 3 to 4 F (18, 582) = 2.56, p < 0.0001) but only the first two functions explained a substantial amount of variance (i.e., 52% and 15%, respectively). Consequently, we only examined the first two functions.

Table 2 presents the standardized canonical function coefficients (canonical weights) and the structure coefficients (canonical loadings;

rs), canonical cross-loadings (i.e., correlation between the individual variable and the opposite canonical variate), as well as the communalities across the two functions (

h2; total variance accounted for by the variable). When interpreting the functions, we consider canonical loadings of

rs > |0.45| as noteworthy. The canonical loading,

rs, is similar to a factor loading in factor analysis or somewhat similar to a standardized beta in multiple regression or a lambda statistic in SEM. The variables are combined based on the canonical loadings to create a synthetic variable. A synthetic variable is somewhat akin to a latent endogenous variable in SEM terms. When considering sexual self-concept as an overarching variable, examination of Function 1 coefficients and loadings indicates that the most relevant sexual self-concept variables were sexual consciousness, fear of sex, sexual self-schema, and sexual optimism (i.e., all

rs > |0.71|). This conclusion is supported by the squared structure coefficients (

rs2) which indicate that consciousness, fear, self-schema, and optimism share the largest amounts of variance with the synthetic variable created from the set of sexual self-concept variables. All other sexual self-concept variables –with the exception of sexual monitoring, which contributed virtually nothing– made moderately-strong secondary contributions to the synthetic variable (i.e.,

rs range |0.42|to |0.64|). This synthetic variable seems to represent an internalized sexual self-concept—incorporating both affective (e.g., fear) and cognitive (e.g., awareness) elements.

In terms of sexual identity development as a latent variable in the first function, the commitment variable was the most relevant based on examination of the standardized canonical function coefficients and structure coefficients (i.e., rs = 0.87). Synthesis/integration and sexual orientation uncertainty contributed moderately strongly to the variance in the synthetic sexual identity development set (i.e., rs = 0.79 and −0.67, respectively). The canonical correlation between the two sets—commitment levels of sexual identity development and internalized sexual self-concept—for the first function was 0.72.

Functions within canonical correlation analyses are independent of each other. The second function (right half of

Table 2) was aimed at accounting for the variance left over after the variance due to the first function was removed. For the second function, which accounted for 15% of the variance above and beyond the 52% accounted for by the first function, sexual monitoring and sexual motivation were the primary variables contributing to the sexual self-concept synthetic variable (i.e.,

rs = 0.61 and 0.57, respectively), with none of the other sexual self-concept variables contributing in any clear, consistent way. For the synthetic sexual identity development variable, sexual orientation uncertainty and exploration were the primary variables accounting for the most variance in the set (i.e.,

rs = 0.74 and 0.65, respectively). Given the variables involved, this function might be labeled “sexual orientation identity and externalization” (a greater explanation and interpretation of this label is presented in the

Section 4). The canonical correlation between the two sets for the second function was 0.38.

3.2. Canonical Correlation between Sexual Identity Development and Comfort with Sexuality

A similar canonical correlation analysis was conducted using the four sexual identity development variables as predictors of the four comfort with sexuality scales in order to evaluate the shared relationships between the two conceptual variables (i.e., sexual identity development and erotophobia–erotophilia). The analysis produced four functions (Rc2 = 0.44, 0.18, 0.07, and 0.00, respectively). The full model was significant (Multivariate F (16, 911) = 18.43, p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.43), with 58% of the variance shared between the two variable sets (i.e., sexual identity development and sexual comfort; Rc = 0.76).

Again, we gain insight into this relationship by examining the canonical correlation (Rc = 0.76) at a deeper, function level. Three of the four functions were statistically significant (Function 1 to 4 F (16, 911) = 18.43, p < 0.0001; Function 2 to 4 F (9, 728) = 9.63, p < 0.0001; and Function 3 to 4 F (4, 600) = 5.67, p < 0.0001) but only the first two functions explained a substantial amount of variance (i.e., 44% and 18%, respectively). Consequently, we examined only these two functions.

Table 3 presents the standardized canonical function coefficients (canonical weights), the structure coefficients (canonical loadings;

rs), canonical cross-loadings (i.e., relationship of the individual variable with the opposite canonical variate; for example, comfort talking about sexuality with the sexual identity development synthetic variable), and the communalities (

h2) across the two functions (i.e., how much variance for which the individual variable accounts across the two functions combined). When considering overall sexual comfort as a latent variable, examination of Function 1 coefficients and loadings indicates that the most relevant sexual comfort variable was comfort with personal aspects of sex (i.e.,

rs = 0.94). This conclusion is supported by the squared structure coefficient (

rs2) of 88%, indicating that this variable shares the largest amount of variance with the synthetic variable created from the set of sexual comfort variables. All other sexual comfort variables, including comfort talking about sex, comfort with the sexuality of others, and comfort with taboo sexual activities of others, made strong, secondary contributions to the synthetic sexual comfort variable (i.e.,

rs = 0.52, 0.58, and −0.57, respectively). Thus, this synthetic variable seems to be a good representation of one’s overall sexual comfort.

In terms of sexual identity development as a predictor variable of sexual comfort in the first function (i.e., one’s own sexual comfort), the synthesis/integration and commitment variables were the most relevant based on examination of the standardized canonical function coefficients and structure coefficients (i.e., rs = 0.89 and 0.76, respectively). Sexual orientation uncertainty and exploration contributed somewhat to the variance in the synthetic sexual identity development set (i.e., rs = −0.63 and 0.31, respectively). The canonical correlation between the two sets (i.e., sexual identity development and personal sexual comfort) for the first function was 0.67.

For the second function emerging within the relationship of sexual comfort and sexual identity development, comfort with the sexuality of others was a strong, primary contributor to the synthetic variable (i.e., rs = 0.66). Following closely, comfort with the taboo sexual activities of others and comfort with talking about sex added to the synthetic comfort variable (i.e., rs = 0.53 and 0.57, respectively). For this synthetic comfort function, comfort with the personal aspects of sexuality had a null structure coefficient (i.e., rs = −0.06); comfort with the personal aspects of sexuality also had a null relationship with the sexual identity development synthetic canonical variate (i.e., cross-loading = 0.03). For this second function, this measure of comfort seems to involve the sexuality in relation to others. The synthetic sexual identity development variable, in the second function, was largely defined by exploration (i.e., rs = 0.89) and, secondarily, by sexual orientation uncertainty (i.e., rs = 0.61). The correlation between sexual identity exploration development and sexual comfort with others’ sexuality, in this second function, was 0.45.

3.3. Canonical Correlation between Sexual Self-Concept and Comfort with Sexuality

We predicted no theoretical directionality as both self-concept and erotophobia–erotophilia might be thought of as unique domains of an individual’s sexual personality or sexual selfhood. Consequently, we would expect them to be correlated. A canonical correlation analysis was conducted using the four sexual comfort variables and the 11 sexual self-concept scales in order to determine the relations between the two conceptual variables. The analysis produced four functions (Rc2 = 0.51, 0.22, 0.10, and 0.07, respectively). The full model was significant (Multivariate F (44, 1108) = 8.64, p < 0.0001, Wilks’ λ = 0.32), with 68% of the variance shared between the two variable sets (i.e., sexual self-concept and sexual comfort; Rc = 0.82).

All four functions were statistically significant (Function 1 to 4 F (44, 1108) = 8.64, p < 0.0001; Function 2 to 4 F (30, 852) = 4.30, p < 0.0001; Function 3 to 4 F (18, 582) = 2.88, p < 0.0001; and Function 4 to 4, F (8292) = 2.57, p = 0.01) but only the first two functions explained a substantial amount of variance (i.e., 51% and 22%, respectively). Consequently, we examined only the first two functions in order to gain a deeper understanding of the relations between sexual self-concept and comfort with sexuality.

Table 4 presents the canonical statistics for the two substantive functions. Considering the first function, the set of sexual self-concept variables consisted primarily of fear of sex, sexual self-schema, sexual consciousness, sexual optimism, and sexual depression (i.e.,

rs = 0.81, −0.79, −0.75, −0.70, and 0.69, respectively), with sexual anxiety, self-efficacy, motivation, and self-esteem contributing to the synthetic variable secondarily (i.e.,

rs = 0.67, −0.65, −0.63 and −0.58, respectively). Only sexual assertiveness and sexual monitoring were insubstantial contributors (i.e.,

rs = −0.37 and 0.01, respectively). This seemed to represent a negative sexual self-concept. (Dis)Comfort with personal aspects of sexuality was paramount in the synthetic comfort with sexuality variable (i.e.,

rs = −0.94). Comfort talking about sex and with the sexuality of others contributed to the synthetic variable secondarily (i.e.,

rs = −0.64 and −0.58, respectively). Comfort with the taboo sexual activities of others was less important but still somewhat relevant within the synthetic variable (i.e.,

rs = 0.44). Function 1, then, appears to be a good representation of most aspects of a negative sexual self-concept and, in particular, one’s personal (dis)comfort vis-à-vis sexuality. The cross-loadings were instructive here as well; most individual sexual self-concept variables –with the exception of sexual monitoring and sexual assertiveness–were moderately correlated with the comfort with sexuality synthetic variable (i.e., cross-loadings of approximately |0.42| to |0.58|). Similarly, the individual comfort with sexuality variables were modestly correlated with the synthetic sexual self-concept variable (i.e., cross-loadings ranging from |0.32| to |0.67|). For function 1, these two synthetic variables of negative sexual self-concept and discomfort with sexuality were correlated 0.72.

While significant, and demonstrating 22% shared variance, the second function was meager (and somewhat unimpressive). That is, only sexual assertiveness demonstrated a substantive contribution to the synthetic variable (i.e., rs = −0.60; and even then, it was relatively weak, sharing only 36% variance–with 45% being the convention for substantial). Following assertiveness, sexual self-esteem, monitoring, and motivation contributed to the synthetic sexual self-concept variable (i.e., rs = −0.44, −0.35, and −0.35, respectively). These might be interpreted to represent the drive to express one’s sexuality. Comfort talking about sex and with the taboo activities of others were the primary contributors to the second function’s comfort with sexuality synthetic variable (i.e., rs = −0.64 and −0.51, respectively). Comfort with the sexuality of others contributed to the comfort with sexuality aggregate slightly (i.e., rs = 0.30), but comfort with personal aspects of sex was irrelevant to this variable (i.e., rs = 0.11). This comfort with sexuality variable might be thought of as more other-focused than the first synthetic comfort aggregate. The cross-loadings were unimpressively low, with the highest coefficients being 0.24 and 0.30. These two synthetic variables were correlated 0.47.

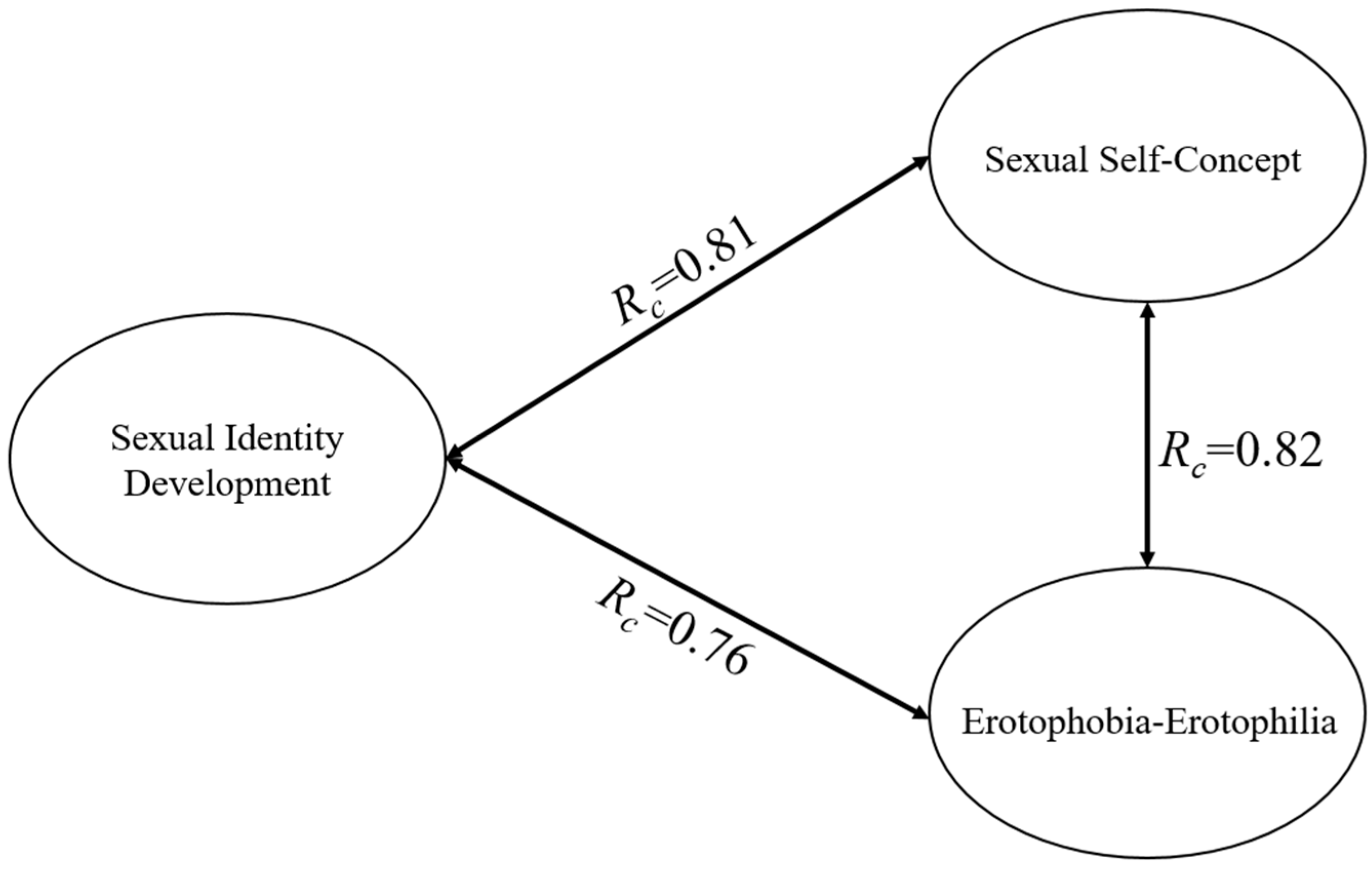

Figure 1 presents the canonical correlations in terms of the hypothesized model. In sum, the correlations supported the hypotheses put forth but we are mindful that these are relationships and causation must not be inferred.

4. Discussion

The canonical correlation analysis presented herein provided an in-depth exploration of the relationships between sexual identity development, sexual self-concept, and erotophobia–erotophilia. The suppositions put forth were supported; sexual identity development, as operationally defined by the variables of the MoSIEC, was predictive of both sexual self-concept and comfort with sexuality, demonstrating relatively strong canonical correlations of 0.81 and 0.76. Sexual self-concept and erotophobia–erotophilia variable sets were strongly interrelated, producing a canonical correlation of 0.82. Canonical correlation analysis allows us to break the multivariate correlations into component parts or functions that underlie these overarching relationships.

4.1. Sexual Identity Development and Sexual Self-Concept

In considering sexual identity development as predicting sexual self-concept, the first function and consequent canonical correlation was quite large and impressive. This function involved most of the MoSIEC variables (with exploration being less relevant) correlating with almost all of the sexual self-concept variables (exception being sexual monitoring). This function seemed to encapsulate sexual identity development integration and overall positive sexual self-concept. That is, having strong sexual identity commitment, high levels of sexual identity synthesis, and low uncertainty about one’s sexual orientation predicted a positive sexual self-concept, including positive sexual self-consciousness, high levels of sexual optimism, and low levels of sexual fear, depression, and anxiety.

The next sexual identity development and sexual self-concept function accounted for much less variance, yet appeared to be worth considering. In this relationship, which we labeled as sexual orientation identity and externalization, the sexual identity development component involved lack of clarity around one’s sexual orientation as well as attempting to learn and explore new areas of one’s sexual self, such as sexual needs, values, likes, etc. In terms of sexual self-concept, sexual monitoring (awareness of how others view one’s sexuality) was key, along with motivation or desire to be in a sexual relationship. This component of sexual self-concept might be considered as describing the dilemma of internalized homophobia; the desire to experience same-sex relations potentially conflicting with the perceived negativity that others, external to the self, have about queer sexuality (perhaps prompting a looking-glass self or social comparison process [

30]). The reason this is interpreted as involving queer sexuality has to do with the strength of the sexual orientation uncertainty variable along with exploration in this second sexual identity development function; these are two variables that would be inherent in the coming out process. These two variables have been found to correlate modestly with sexual orientation self-concept ambiguity [

31]. This secondary canonical relationship is likely specific to or driven by those participants who were in an early state of exploration, perhaps actively questioning who they are as sexual beings.

4.2. Sexual Identity Development and Comfort with Sexuality

Regarding sexual identity development as it theoretically influences erotophobia–erotophilia, two functions were also relevant. The first function involved almost all of the sexual identity variables (although exploration was a weak contributor) in the relationship with sexual comfort. Similarly, all of the sexual comfort indicators contributed to the first function; however, comfort with the personal aspects of sexuality was particularly strong. This might suggest that an overall sexual identity development process is strongly predictive of one’s personal comfort with sexuality. Those whose sexual identity was relatively developed, that is, high on sexual identity synthesis and exploration, and low on sexual orientation uncertainty, tended to be highly comfortable with their own personal sexuality, comfortable with the sexuality of other people, and amenable to talking about sexuality.

The relationship in the second function between sexual identity development and erotophobia–erotophilia was due primarily to the exploration and sexual orientation uncertainty in sexual identity development and comfort with the sexuality of others (as well as talking about sex and taboo sexual activities of others). The erotophobia–erotophilia component of the second function appears to be very other-focused. While we have hypothesized that sexual identity development is shaping erotophobia–erotophilia, the causality could go in the other direction. For example, it could be comfort with other people’s sexuality, with discussing sex (with others), and with unusual sexual activities in which others engage that could prompt one’s own sexual exploration process (i.e., exploring and calling one’s sexual orientation into question). The relationship could be bidirectional or a third variable could be responsible for the correlation between the two.

4.3. Relation between Sexual Self-Concept and Comfort with Sexuality

Finally, the canonical correlation analysis supported the hypothesized relationship between sexual self-concept and erotophobia–erotophilia. Generally, those who demonstrated greater discomfort with sexuality had a more negatively-defined sexual self-concept. The first function was representative of the relationship between overall sexual self-concept and personal comfort with sexuality, while the interpretation of the second function may be that it was based primarily on verbalization around sexuality. Sexual assertiveness was the sole sexual self-concept variable involved in the second function vis-à-vis erotophobia–erotophilia. While Snell [

8] describes the scale as being assertive about what one wants sexually (i.e., assertiveness versus passiveness in relation to expressing one’s sexual desires), the scale items are phrased such that they describe asking for or expressing one’s sexual wants, which was then related to comfort in talking with others about sex (as well as being comfortable with other people’s taboo activities). This could represent a sexual communication component that is somewhat distinct from overall sexual self-concept and overall comfort with sexuality; this needs to be explored further.

4.4. Limitations and Future Research

An issue associated with this research area is the operational and conceptual definitions of the theoretical constructs. While there is some agreement of the components that constitute sexual self-concept [

12], there is no consensus on which instruments best measure sexual self-concept [

6]. Furthermore, there is some inconsistency in the theoretical definition of the construct of sexual self-concept. For example, Muise, Preyde, Maitland, and Milhausen [

25] assessed the relationship between sexual identity development (also using the MoSIEC) and sexual well-being. Their operationalization of sexual well-being involved variations on several of the scales we used as indicators of sexual self-concept; in particular, sexual self-esteem, sexual consciousness, and sexual assertiveness [

8,

24,

32,

33]. Muise et al. [

25] also included satisfaction with sexual relationships as well as body appearance esteem/evaluation as indicators of sexual well-being. What Muise et al. [

25] label well-being could be conceptually similar to what we have called sexual personality. It certainly makes sense to define sexual well-being as including all positive/favorable sexual self-concepts, but it is also logical to argue that sexual self-concept is a component of one’s sexual personality along with other components such as erotophobia–erotophilia. Neither conceptualization is wrong, but neither is definitively correct. The lack of definitional consensus and inconsistent use of sexual self-concept variables is a controversy in this emerging field [

11,

12,

13].

Similarly, there are other ways that the sexual identity development process could have been measured. For instance, the Utrecht-Management of Identity Commitments scale (U-MICS [

34,

35]) is a general scale based on the Marcia identity status model which can be adapted for various domains. It has fewer dimensions (i.e., exploration, commitment, and reconsideration of commitment) than the MoSIEC and thus may be more parsimonious. An advantage of using the U-MICS to measure sexual identity development is that its ability to adapt to different domains allows for comparisons across domains (e.g., sexual versus ethnic identity development). On the other hand, an advantage of the MoSIEC is its specificity to sexual identity—it covers some identity development domains (e.g., sexual orientation uncertainty) that may have no parallel in other identity development measures. Furthermore, erotophobia–erotophilia can be measured with other instruments such as the Sexual Opinion Survey [

19] or the Sexual Anxiety Scale [

36]. Using different instruments could provide support for the robustness of the theorized relationships.

The relationships proposed by the logical rationale outlined here should hold regardless of the instruments used. It makes theoretical sense for sexual identity development to shape, precede, or predict sexual self-concept. Sexual self-concept would likely be formed as a result of such development; how we think about and know our sexual self is a function of the process of developing as a sexual being. Similarly, the sexual identity development process likely influences how comfortable one is with sexuality; if the identity process were unpleasant, it likely would reinforce erotophobia. Contrastingly, a positive identity process (e.g., high synthesis, high commitment, high exploration, low sexual orientation uncertainty) might foster more erotophilic tendencies. If sexual self-concept and erotophobia–erotophilia are part of our sexual personality, it makes sense that these are correlated as well. While the current data support these hypothesized relationships, they do not address causality. As a next step, these theoretical propositions should be tested with advanced modeling techniques using longitudinal designs and experimental investigations.

Use of this Canadian university sample has the inherent limitations of student-based and online studies—in addition to those who volunteer for sexuality research [

37,

38,

39,

40,

41,

42]. A student sample is a weakness and a strength of this study. We cannot generalize from a student sample to the general population; students are somewhat more sexually liberal in their attitudes compared to the general public, but students are heterogeneous in these attitudes relative to representative samples [

43]. Emerging adulthood is considered a distinctive developmental life stage with an intense and serious focus on sexuality, love, and romantic relationship identity exploration [

44]. An emerging adult sample offers unique insight, as sexual identity is in the process of formation and change [

45]. Future research should attend to differences cross-culturally regarding sexuality with consideration of such biopsychosocial factors as socioeconomic status, age, education, sexual orientation and gender diversity, and societal conservatism [

12,

13,

26,

46].