Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions Related to Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Perpetrated by UN Peacekeepers during MINUSTAH

Abstract

:1. Introduction

1.1. The UN’s Zero-Tolerance Policy

1.2. Haitian Context Regarding Sexual and Romantic Relationships

1.3. Criminal Immunity

1.4. Peacekeeper-Fathered Children (Peace Babies)

1.5. UN’s Institutional Response to SEA

1.6. Gender Norms

Social norms defining acceptable and appropriate actions for women and men in a given group or society. They are embedded in formal and informal institutions, nested in the mind, and produced and reproduced through social interaction. They play a role in shaping women’s and men’s (often unequal) access to resources and freedoms, thus affecting their voice, power and sense of self.

1.7. Gender and Peacekeeping Operations

1.8. Purpose

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

2.2. SenseMaker

2.3. Participant Accrual

2.4. Data Analysis

2.5. Contextualizing the Quantitative Results Using Narratives

2.6. Ethics

3. Results

3.1. Sample

3.1.1. Characteristics of the Narrators (Participants)

3.1.2. Narrative Characteristics

3.2. Descriptive Results: Gender Differences

After the earthquake, I had two kids who were in an accident. I had a friend … who was on his way to MINUSTAH’s office, he was bringing his children to get care at the MINUSTAH’s office, the office in Tabarre. I brought my kids there as well. At the time, it was true we received care, people at the MINUSTAH’s office provided good care, the kids survived. To this day, the kids are [still] doing very well, they have no issues.(Tabarre, 45–54 years old)

The MINUSTAH caused a lot of chaos, especially with young ladies, because they made promises to the ladies, like they would say that they are going to pay for their school, allow them to go to the university, but nothing has materialized. The MINUSTAH put a lot of divisions between parents and the ladies, even though we knew they were not there for long, but they left a lot of issues in the area.(Hinche, 25–34 years old)

The MINUSTAH had a base here, they always had time off and time to go to the beach. So, I met with one, we talked, then we became friends, afterwards he came to my home often, then the friendship went further, and after a lot of time we were in love. I was 17 years old and he had a party for me and we started a sexual relationship. So, I became pregnant and then my parents found out. They put him in jail for a month and he went back to his country. When he got there, I used to call him, he sent me money until I gave birth, since then I have not heard from him again. It has been 1 year and 9 months. Now I am caring for the child, send him to school. I am just suffering with him because I have no longer heard from his dad. Although many people tried to reach him, nothing ever happened.(Port Salut, 18–24 years old)

MINUSTAH generally helps the national police on election days, when we have elections. Well, when elections do happen. They stop chaotic fights among opposing parties from happening. They brought cholera. Sometimes, it’s hard to see how they help the country by bringing in diseases. Other countries provide aid to eradicate cholera in the country. It’s not the UN that gives aid toward this disease. Other places, like the US, Cuba, they are the ones who brought aid to combat cholera; in Haiti though, MINUSTAH was the one to bring it in.(Hinche, 18–24 years old)

I have a child that was fathered by a MINUSTAH member. I spent quite a bit of time with the MINUSTAH [peacekeeper]. He used to come to my house. I became pregnant. We were still together while I was pregnant, up to the time when I gave birth. Then his tour of duty ended, he went back to his country, and ever since, I do not have any information about him. As the child is growing up, I do not hear about him anymore. He does not call me. Now I have to be the one to educate this child, take care of his health and shelter.(Port Salut, 35–44 years old)

Well, it hurts me to watch what MINUSTAH are doing in Cité Soleil. They raped many children, and the children are underage. Because of the small portion of food and the money that they gave them, they raped them. Some of them got pregnant; A kid will be the mother to another kid. MINUSTAH are the ones who give a lot of trouble in Cite Soleil. MINUSTAH needs to leave the country because too many kids get impregnated…I demand justice for women and children who are getting pregnant.(Cité Soleil, 35–44 years old)

I thought that the MINUSTAH, when they came to the country, would help in developing the country, build infrastructures and schools. Although the presence of the MINUSTAH was in my profit because they hired me and I made my money with them as a carpenter, I thought they would invest more in education and other more concrete projects. If they sponsor a project for the public, they would facilitate their friends to get the project over someone else.(Morne Casse/Fort Liberté, 25–34 years old)

I met a MINUSTAH because he used to come to my house where I was selling beers. I started to talk to him, then he told me he loved me and I agreed to date him. Three months later, I was pregnant, and in September, he was sent to his country. He started sending money for the child for 2 months, but ever since, I have not heard from him. The child is growing up, and it’s myself and my family that are struggling with him. I now have to send him to school. They put him out because I’m unable to pay for it. At the time, it was true I had my aunt who wanted to adopt him as her son, but I did not have the heart to do it. It took all my strength, and I agreed because I do not have any help.(Port Salut, 25–34 years old)

The young girls, children of Cité Soleil they always like whites/foreigners. As soon as they see a foreigner, they always approach him. But it also happened that one came to have a relationship with them. They came to make [children]. Twins … up to the present moment, they haven’t taken care of them … Also, I know a lot of children that are living with MINUSTAH children … When a foreigner that has the means in their hands, that has things they can do, that does something bad like that. That makes me say the act, because if you do it, if you get a girl pregnant, they have a child with her. But you can’t take care of it, it’s a dishonest act. It’s a crime …Well, today those children are growing up without fathers. But the mothers know that your father is a MINUSTAH soldier.(Cité Soleil, 25–34 years old)

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Findings

4.2. Contribution to Gendered Peacekeeping Discourses

4.3. UN Trust Fund for Victims of SEA

4.4. Limitations

4.5. Strengths

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. SenseMaker® Cross-Sectional Survey

- Prompting Questions:

- Describe the best or worst experience of a particular woman or girl in your community who has interacted with foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel. What happened?

- Describe how living in a community with a UN or MINUSTAH presence has provided either a particular opportunity or a danger to a particular woman or girl in the community. What happened?

- Describe the negative or positive experience of a particular women or girl who requested support or assistance after interacting with foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel. What happened?

- Triad Questions:

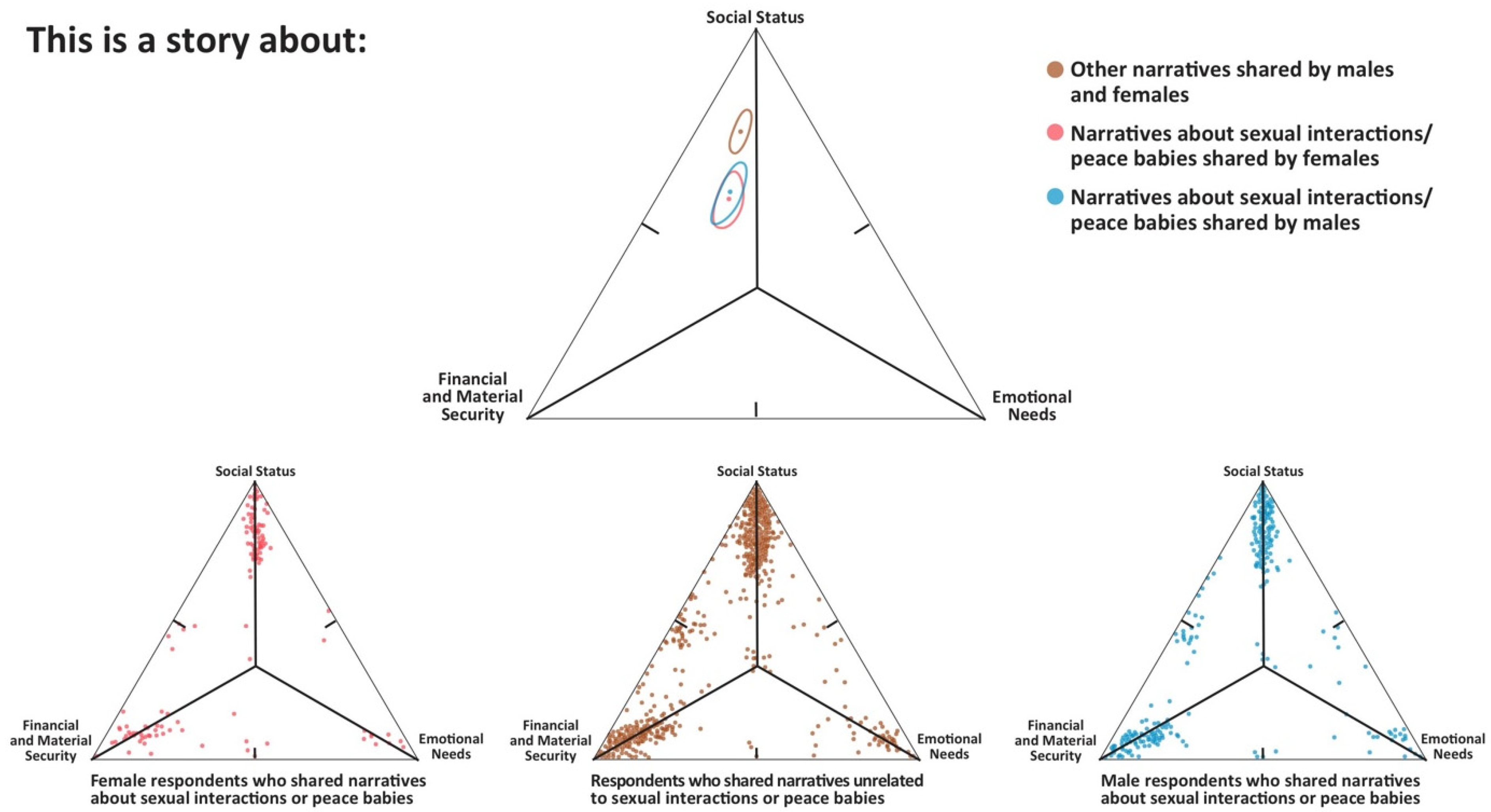

- This story is about: 1. Financial/material security, 2. Social status, 3. Emotional needs.

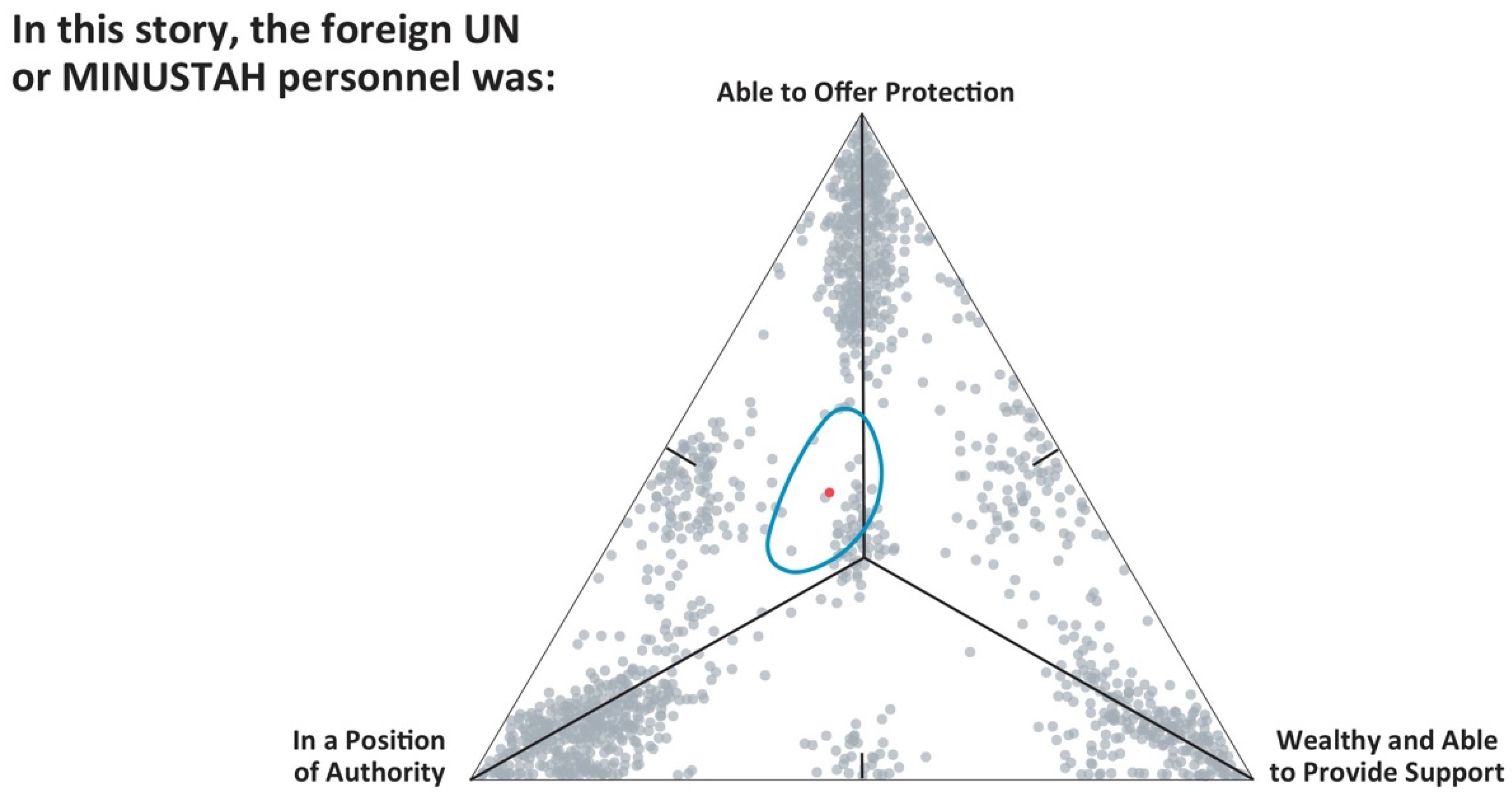

- In this story, the foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel was: 1. In a position of authority, 2. Able to offer protection, 3. Wealthy and able to provide support.

- Was the interaction in the story: 1. Friendly, 2. Business, 3. Relationship.

- In the story, what would a fair response look like? 1. Acceptance of responsibility, 2. Justice, 3. Reparation.

- In the story, it would have helped the woman or girl most to have had support from: 1. The UN or MINUSTAH, 2. NGOs or civil society organizations, 3. Haitian authorities.

- In the story, barriers to the woman or girl getting a fair response were: 1. Lack of information in the community about assistance, 2. Lack of response from Haitian authorities, 3. Lack of response from the UN or MINUSTAH.

- In the story, what would have helped most to make the experience more positive: 1. Material/financial support, 2. Emotional support, 3. Legal support.

- Based on the events in the story, the presence of the UN or MINUSTAH led to: 1. Disrespect of Haitian values and laws, 2. Negative financial impact, 3. Anger and resentment.

- Multiple Choice Questions Pertaining to the Narrative:

- (M1)

- Who is the story about?

- -

- About me

- -

- About someone in my household

- -

- About someone in my family who doesn’t live in my household

- -

- About a friend

- -

- Community

- -

- Something I heard or read about

- -

- Prefer not to say

- (M2)

- How often does the situation in this story occur?

- -

- Very rarely

- -

- Occasionally

- -

- Regularly

- -

- Very frequently

- -

- All the time

- -

- Not sure

- (M3)

- How important is it for others to hear and learn from your story

- -

- Must hear this story and take action

- -

- Should definitely hear this story and pay attention

- -

- Can learn something

- (M4)

- Who would most benefit from hearing the story shared? (choose up to three)

- -

- Family

- -

- Friends

- -

- Neighbors

- -

- Haitian politicians

- -

- The UN or MINUSTAH

- -

- NGOs

- -

- The military of the foreigner

- -

- Churches

- -

- Community leaders

- -

- Business people

- -

- Girls in my community

- -

- Women in my community

- -

- Men in my community

- -

- Not sure

- (M5)

- What is the emotional tone of this story?

- -

- Strongly positive

- -

- Positive

- -

- Neutral

- -

- Negative

- -

- Very negative

- -

- Not sure

- (M6)

- How does your story make you feel (choose up to 3):

- -

- Angry

- -

- Disappointed

- -

- Embarrassed

- -

- Encouraged

- -

- Frustrated

- -

- Good

- -

- Happy

- -

- Hopeful

- -

- Indifferent

- -

- Relieved

- -

- Sad

- -

- Satisfied

- -

- Worried

- -

- Not sure

- (M7)

- What country was the foreigner in the story from?

- -

- Uruguay

- -

- Sri Lanka

- -

- Pakistan

- -

- Nepal

- -

- Argentina

- -

- Bolivia

- -

- Brazil

- -

- Chile

- -

- Peru

- -

- Indonesia

- -

- Jordan

- -

- Nigeria

- -

- Pakistan

- -

- Indonesia

- -

- Senegal

- -

- United States

- -

- France

- -

- Canada

- -

- Japan

- -

- China

- -

- Other

- -

- Don’t know

- (M8)

- What was the role of the foreigner with the UN or MINUSTAH?

- -

- Soldier (UNPOL, MINUSTAH, or Multinational Forces)

- -

- Civilian who works with the UN (doesn’t wear a uniform)

- -

- Police

- -

- Worked for an NGO rather than the UN or MINUSTAH

- -

- Other

- -

- Don’t know

- Multiple Choice Questions Pertaining to the Participant:

- (D1)

- What is your gender?

- -

- Female

- -

- Male

- -

- Prefer not to say

- (D2)

- How old are you:

- -

- 11–17 years old

- -

- 18–24 years old

- -

- 25–34 years old

- -

- 35–44 years old

- -

- 45–54 years old

- -

- ≥55 years old

- (D3)

- What is your marital status?

- -

- Married or living together as if married

- -

- Divorced/Separated from spouse

- -

- Widowed

- -

- Single, never married

- -

- Prefer not to say

- (D4)

- What is your highest educational qualification?

- -

- No formal education

- -

- Some primary school

- -

- Completed primary school

- -

- Some secondary school

- -

- Completed secondary school

- -

- Some post-secondary school

- -

- Completed post-secondary school

- (D5)

- I’ll read you a list of 5 items that some people have at home. Please tell me which of these you or your household owns. Your household consists of people who sleep under the same roof and eat the same meals. Chose as many as your family has:

- -

- radio

- -

- mobile phone

- -

- refrigerator or freezer

- -

- vehicle such as a truck, a car or a motorcycle

- -

- generator, inverter, or sun panel that provides electricity to your home.

- -

- None of the above

- (D6)

- Here are some questions about your life

- -

- 7 Strongly agree

- -

- 6 Agree

- -

- 5 Slightly agree

- -

- 4 Neither agree nor disagree

- -

- 3 Slightly disagree

- -

- 2 Disagree

- -

- 1 Strongly disagree

- Multiple Choice Questions for the Research Assistant (not presented or answered by the participants)

- (I1)

- Which category/group does this narrator belong?

- -

- Child fathered by foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Woman or girl who had interacted with foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Family member of a woman or girl who had interacted with foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Friend of a woman or girl who had interacted with foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Community member where foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel are hosted

- -

- Community leader where foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel are hosted

- -

- Foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Haitian UN or MINUSTAH personnel

- -

- Politician

- -

- NGO staff

- -

- Other

- (I2)

- In what location was the interview conducted?

- -

- Cité Soleil

- -

- Charlie Log Base/Tabarre

- -

- Gonaives

- -

- St. Marc

- -

- Hinche

- -

- Leogane

- -

- Port Salut

- -

- Miragoane

- -

- Morne Casse/Fort Liberté

- -

- Cap Haitien

- (I3)

- Do you think the participant was comfortable taking part in this survey? (choose up to three)

- -

- No—because of the survey

- -

- No—because of the topic

- -

- No—because of the iPad

- -

- No—because of the voice recording

- -

- No—because of the SenseMaker questions

- -

- No—because of concerns about motivations or identity of the researchers

- -

- No—because of voodoo-related fears or concerns

- -

- No—other

- -

- Yes

- -

- Not sure

- (I4)

- Was this story about a peace baby?

- -

- About a peace baby

- -

- Mentioned a peace baby

- -

- About sexual abuse or exploitation by UN or MINUSTAH but not a peace baby

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- (I5)

- Was this story about cholera?

- -

- About cholera

- -

- Mentioned cholera

- -

- About wrongdoings committed by foreign UN or MINUSTAH personnel but not about cholera

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- (I6)

- Would you flag this story for translation and further analysis based on richness or interest?

- -

- Yes

- -

- No

- -

- Not sure

- (I7)

- Which story number is this for this participant?

- -

- 1st

- -

- 2nd

- -

- 3rd

- -

- 4th

References

- Jennings, K. The Immunity Dilemma: Peacekeepers’ Crimes and the UN’s Response. Available online: http://www.e-ir.info/2017/09/18/the-immunity-dilemma-peacekeepers-crimes-and-the-uns-response/ (accessed on 14 October 2020).

- Hultman, L.; Kathman, J.D.; Shannon, M. Peacekeeping in the Midst of War; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grewal, B.S. Johan Galtung: Positive and Negative Peace; Auckland University of Technology: Aukland, Australia, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Hatto, R. From peacekeeping to peacebuilding: The evolution of the role of the United Nations in peace operations. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2014, 95, 495–515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Willmot, H.; Sheeran, S. The protection of civilians mandate in un peacekeeping operations: Reconciling protection concepts and practices. Int. Rev. Red Cross 2014, 95, 517–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Heine, J.; Thompson, A. Introduction: Haiti’s governance challenges and the international community. In Fixing Haiti: MINUSTAH and Beyond; Heine, J., Thompson, A., Eds.; United Nations University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations MINUSTAH: United Nations Peacekeeping. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minustah (accessed on 4 February 2020).

- United Nations Peacekeeping United Nations Stabilization Mission in Haiti (MINUSTAH). Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/mission/minustah (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- Connors, J. A victims’ rights approach to the prevention of, and response to, sexual exploitation and abuse by United Nations personnel. Aust. J. Hum. Rights 2019, 25, 498–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations Conduct in UN Peace Missions: Sexual Exploitation and Abuse. Available online: https://conduct.unmissions.org/sea-overview (accessed on 21 March 2020).

- Beber, B.; Gilligan, M.J.; Guardado, J.; Karim, S. Peacekeeping, compliance with international norms, and transactional sex in Monrovia, Liberia. Int. Organ. 2017, 71, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neudorfer, K. Sexual Exploitation and Abuse in UN Peacekeeping: An Analysis of Risk and Prevention Factors; Lexington Books: London, UK, 2015; ISBN 978-0-7391-9961-9. [Google Scholar]

- Nordås, R.; Rustad, S.C.A. Sexual exploitation and abuse by peacekeepers: Understanding variation. Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 511–534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Jazeera Uruguay Apologises over Alleged Rape in Haiti|Environment News|Al Jazeera. Available online: https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2011/9/7/uruguay-apologises-over-alleged-rape-in-haiti (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- A Scandal of Sexual Abuse Mars the UN’s Exit from Haiti 2017. The Washington Post. Available online: https://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/a-scandal-of-sexual-abuse-mars-the-uns-exit-from-haiti/2017/04/16/d6947bde-213a-11e7-ad74-3a742a6e93a7_story.html (accessed on 16 April 2017).

- Williams, C.J. UN Confronts Another Sex Scandal—Los Angeles Times. Available online: https://www.latimes.com/archives/la-xpm-2007-dec-15-fg-haitisex15-story.html (accessed on 6 April 2021).

- United Nations Secretariat. Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Sexual Abuse; United Nations: Geneva, Switzerland, 2003.

- Jennings, K.M. Protecting Whom? Approaches to Sexual Axploitation and Abuse UN Peacekeeping Operations; Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs: Oslo, Norway, 2008.

- Vahedi, L.; Bartels, S.; Lee, S. “His Future will not be Bright”: A qualitative analysis of mothers’ lived experiences raising peacekeeper-fathered children in Haiti. Child. Youth Serv. Rev. 2020, 119, 105625. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahedi, L.; Bartels, S.A.; Lee, S. ‘Even peacekeepers expect something in return’: A qualitative analysis of sexual interactions between UN peacekeepers and female Haitians. Glob. Public Health 2019, 1692, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Bartels, S. ‘They Put a Few Coins in Your Hand to Drop a Baby in You’: A Study of Peacekeeper-fathered Children in Haiti. Int. Peacekeeping 2020, 27, 177–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanetake, M. Whose zero tolerance counts? Reassessing a zero tolerance policy against sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers. Int. Peacekeeping 2010, 17, 200–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGill, J. Survival sex in peacekeeping economies: Re-reading the zero tolerance approach to sexual exploitation and sexual abuse in United Nations peace support operations. J. Int. Peacekeeping 2014, 18, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Otto, D. Making sense of zero tolerance policies in peacekeeping sexual economies. In Sexuality and the Law: Feminist Engagements; Munro, V., Stychin, C.F., Eds.; GlassHouse Press: London, UK, 2007; pp. 259–282. ISBN 9780203945094. [Google Scholar]

- Simi, B.O.; United Nations; Westendorf, J.-K.; Searle, L.; Spangaro, J.; Adogu, C.; Ranmuthugala, G.; Powell Davies, G.; Steinacker, L.; Zwi, A.; et al. Sexual exploitation and abuse by UN peacekeepers: A threat to impartiality. Int. Peacekeeping 2017, 17, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, O.; O’Brien, M. “Peacekeeper babies”: An unintended legacy of United Nations peace support operations. Int. Peacekeeping 2014, 21, 345–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faedi, B. The double weakness of girls: Discrimination and sexual violence in Haiti. Stanford J. Int. Law 2008, 44, 147–204. [Google Scholar]

- Dupuy, A. Haiti: From Revolutionary Slaves to Powerless Citizens: Essays on the Politics and Economics of Underdevelopment; Routeledge: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Diehl, P.F. Peace Operations (War and Conflict in the Modern World), 1st ed.; Polity Press: Cambridge, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, M. Domestic violence in the Haitian culture and the American legal response: Fanm ahysyen ki gen kouraj. Univ. Miami Inter Am. Law Rev. 2006, 37, 297–317. [Google Scholar]

- Immigration and Refugee Board of Canada Haiti: Violence against Women, Including Sexual Violence; State Protection and Support Services (2012–June 2016). Available online: https://www.refworld.org/docid/58d539d04.html (accessed on 7 March 2021).

- Reiz, N.; O’Lear, S. Spaces of Violence and (In)justice in Haiti: A Critical Legal Geography Perspective on Rape, UN Peacekeeping, and the United Nations Status of Forces Agreement. Territ. Polit. Gov. 2016, 4, 453–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fox, C. Violent sex: How gender-based violence is structured in Haiti, healthcare & HIV/AIDS. Indiana J. Law Soc. Enq. 2013, 2, 202–229. [Google Scholar]

- Kolbe, A.R. ‘It’s Not a Gift When It Comes with a Price’: A Qualitative Study of Transactional Sex between UN Peacekeepers and Haitian Citizens. Stab. Int. J. Secur. Dev. 2015, 4, 1–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Daniel, C.A.; Logie, C. Transactional Sex among Young Women in Post-Earthquake Haiti: Prevalence and Vulnerability to HIV. J. Sociol. Soc. Work 2017, 5, 54–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Charter of the United Nations and Statute of the Charter of the International Court of Justice; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 1945; Volume 55, ISBN 9789210020251.

- Simm, G. Sex in Peace Operations; Oxford Universiry Press: Oxford, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Blau, L. Victimizing those they were sent to protect: Enhancing accountability for children born of sexual abuse and exploitation by UN peacekeepers. Syracuse J. Int. Law Commer. 2016, 44, 122–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ndulo, M. The United Nations Responses to the Sexual Abuse and Exploitation of Women and Girls by Peacekeepers during Peacekeeping Missions Peacekeeping Missions. Berkeley J. Int’l Law 2009, 27, 127. [Google Scholar]

- Rehn, E.; Sirleaf, E. Women, War and Peace: The Independent Experts’ Assessment on the Impact of Armed Conflict on Women and Women’s Role in Peace-Building; UN Women: New York, NY, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations. Resolution 62/214: United Nations Comprehensive Stragety on Assistance and Support to Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse by United Nations Staff and Related Personnel; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2008.

- United Nations Secretariat. A Comprehensive Strategy to Eliminate Future Exploitation and Abuse in United Nations Peacekeping Operations; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2005; Volume 24790.

- Notar, S.A. Peacekeepers as perpetrators: Sexual exploitation and abuse of women and children in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. J. Gender Soc. Policy Law 2006, 14, 413–429. [Google Scholar]

- United Nations Secretary General. Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploutation and Abuse; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2020.

- United Nations. Peacekeeping Disciplinary Processes|Conduct in UN Field Missions. Available online: https://conduct.unmissions.org/enforcement-disciplinary (accessed on 1 April 2020).

- United Nations Secretary General. Special Measures for Protection from Sexual Exploitation and Abuse: A New Approach Report; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2017.

- Cislaghi, B.; Heise, L. Gender norms and social norms: Differences, similarities and why they matter for effective global health action. Sociol. Health Illn. 2019, 42, 407–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- United Nations. Women Women, Peace and Security|UN Women—Headquarters. Available online: https://www.unwomen.org/en/news/in-focus/women-peace-security (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- United Nations. United Nations Security Council Resolution 1325 (2000) on Women, Peace and Security: Understanding the Implications, Fulfilling the Obligations; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2000; Volume 1325, ISBN 1212963180.

- Henry, M.G. Keeping the peace: Gender, geopolitics and global governance interventions. Confl. Secur. Dev. 2019, 19, 263–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higate, P. Peacekeepers, masculinities, and sexual exploitation. Men Masc. 2007, 10, 99–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleckner, J. From Rhetoric to reality: A pragmatic analysis of the integration of women into un peacekeeping operations. J. Int. Peacekeeping 2013, 17, 337–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S. Reevaluating peacekeeping effectiveness: Does gender neutrality inhibit progress? Int. Interact. 2017, 43, 822–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, S.; Beardsley, K. Female peacekeepers and gender balancing: Token gestures or informed policymaking? Int. Interact. 2013, 39, 461–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jennings, K.M.; Nikolić-Ristanović, V. UN Peacekeeping Economies and Local Sex Industries: Connections and Implications; MICROCON: Brighton, UK, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Cognitive Edge about Us: Cognitive Edge. Available online: http://cognitive-edge.com/about-us/ (accessed on 21 June 2018).

- Girl Hub. Using Sensemaker® to Understand Girls’ Lives: Lessons Learnt; Girls not Brides: London, UK, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bartels, S.A.; Michael, S.; Roupetz, S.; Garbern, S.; Kilzar, L.; Bergquist, H.; Bakhache, N.; Davison, C.; Bunting, A. Making sense of child, early and forced marriage among Syrian refugee girls: A mixed methods study in Lebanon. BMJ Glob. Health 2018, 3, e000509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fleming, P.J.; Wallace, J.J. How not to lie with statistics: The correct way to summarize benchmark results. Commun. ACM 2002, 29, 218–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, S. Statistics in the Triad, Part I: Geometric Mean. Available online: http://qedinsight.com/2016/03/28/geometric-mean/ (accessed on 11 March 2019).

- Csaky, C. No One to Turn To No One to Turn To; Save the Children: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Diaz Perez, A.; Vega Ochoa, A.D.; Oñate, Z.R. The Informed Consent/Assent from the Doctrine of the Mature Minor. Glob. J. Health Sci. 2018, 10, 124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weir, K. Studying Adolescents without Parents’ Consent: A New APA Resolution Supports Mature Minors’ Participation in Research without Parental Permission. Available online: https://www.apa.org/monitor/2019/02/parents-consent (accessed on 3 April 2020).

- United Nations Peacekeeping Women in Peacekeeping|United Nations Peacekeeping. Available online: https://peacekeeping.un.org/en/women-peacekeeping (accessed on 18 March 2020).

- Linos, N. Rethinking gender-based violence during war: Is violence against civilian men a problem worth addressing? Soc. Sci. Med. 2009, 68, 1548–1551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Touquet, H.; Gorris, E. Out of the shadows? The inclusion of men and boys in conceptualisations of wartime sexual violence. Reprod. Health Matters 2016, 24, 36–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Higate, P.; Henry, M. Engendering (in)security in peace support operations. Secur. Dialogue 2004, 35, 461–478. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simić, O. Rethinking “sexual exploitation” in UN peacekeeping operations. Womens. Stud. Int. Forum 2009, 32, 288–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Jennings, K.M.; Bøås, M. Transactions and interactions: Everyday life in the peacekeeping economy. J. Interv. Statebuild. 2015, 9, 281–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mudgway, C. Sexual exploitation by UN peacekeepers: The ‘survival sex’ gap in international human rights law. Int. J. Hum. Rights 2017, 21, 1453–1476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoebenau, K.; Heise, L.; Wamoyi, J.; Bobrova, N. Revisiting the understanding of “transactional sex” in sub-Saharan Africa: A review and synthesis of the literature. Soc. Sci. Med. 2016, 168, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Defeis, E.F. U.N. Peacekeepers and Sexual Abuse and Exploitation: An End to Impunity. Washingt. Univ. Glob. Stud. Law Rev. 2008, 7, 185–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freedman, R. UN immunity or impunity? A human rights based challenge. Eur. J. Int. Law 2014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Freedman, R. UNaccountable: A New Approach to Peacekeepers and Sexual Abuse. Eur. J. Int. Law 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United Nations. 2017 and 2018 Report: Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- United Nations. 2019 Update: Trust Fund in Support of Victims of Sexual Exploitation and Abuse; United Nations: New York, NY, USA, 2019.

- United Nations. United Nations Treaty Collection. Available online: https://treaties.un.org/pages/ViewDetails.aspx?src=TREATY&mtdsg_no=IV-8&chapter=4&clang=_en (accessed on 18 April 2021).

- République d’Haïti. Plan National 2017–2027 de Lutte Contre les Violences Envers les Femmes; République d’Haïti: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ministère de la Santé Publique. Politique Nationale de Recherche en Santé Publique et de la Population; Ministère de la Santé Publique: Port-au-Prince, Haiti, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, G.M.; Young, L.E. Cooperation, information, and keeping the peace: Civilian engagement with peacekeepers in Haiti. J. Peace Res. 2017, 54, 64–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhache, N.; Michael, S.; Roupetz, S.; Garbern, S.; Bergquist, H.; Davison, C.; Bartels, S. Implementation of a SenseMaker® research project among Syrian refugees in Lebanon. Glob. Health Action 2017, 10, 1362792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Bartels, S.A.; Michael, S.; Vahedi, L.; Collier, A.; Kelly, J.; Davison, C.; Scott, J.; Parmar, P.; Geara, P. SenseMaker® as a Monitoring and Evaluation Tool to Provide New Insights on Gender- Based Violence Programs and Services in Lebanon. Eval. Program Plann. 2019, 77, 101715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Demographic Characteristic | All Respondents [n (%)] |

|---|---|

| Education | |

| No formal education | 118 (5.4) |

| Some primary school | 269 (12.3) |

| Completed primary school | 250 (11.4) |

| Some secondary school | 831 (37.9) |

| Completed secondary school | 416 (19.0) |

| Some post-secondary school | 217 (9.9) |

| Completed post-secondary school | 90 (4.1) |

| Income * | |

| Poor | 670 (30.6) |

| Average | 1386 (63.3) |

| Well-off | 135 (6.2) |

| Gender | |

| Female | 664 (30.3) |

| Male | 1526 (69.6) |

| Prefer not to say | 1 (0.05) |

| Age | |

| 11–17 years old | 216 (9.9) |

| 18–24 years old | 508 (23.2) |

| 25–34 years old | 724 (33.0) |

| 35–44 years old | 360 (16.4) |

| 45–54 years old | 206 (9.4) |

| >55 years old | 127 (5.8) |

| Prefer not to say | 48 (2.2) |

| Missing | 2 (0.09) |

| Location ** | |

| Cap Haitien | 246 (11.2) |

| Charlie Log Base and Tabarre | 168 (7.7) |

| Cité Soleil | 341 (15.6) |

| Hinche | 303 (13.8) |

| Leogane | 314 (14.3) |

| Morne Casse and Fort Liberté | 192 (8.8) |

| Port Salut | 313 (14.3) |

| Saint Marc and Gonaives | 314 (14.3) |

| Marital Status | |

| Divorced/Separated from spouse | 18 (0.8) |

| Married or living together as if married | 796 (36.3) |

| Single, never married | 1326 (60.5) |

| Widowed | 15 (0.7) |

| Prefer not to say | 36 (1.6) |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Vahedi, L.; Stuart, H.; Etienne, S.; Lee, S.; Bartels, S.A. Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions Related to Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Perpetrated by UN Peacekeepers during MINUSTAH. Sexes 2021, 2, 216-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2020019

Vahedi L, Stuart H, Etienne S, Lee S, Bartels SA. Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions Related to Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Perpetrated by UN Peacekeepers during MINUSTAH. Sexes. 2021; 2(2):216-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2020019

Chicago/Turabian StyleVahedi, Luissa, Heather Stuart, Stéphanie Etienne, Sabine Lee, and Susan A. Bartels. 2021. "Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions Related to Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Perpetrated by UN Peacekeepers during MINUSTAH" Sexes 2, no. 2: 216-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2020019

APA StyleVahedi, L., Stuart, H., Etienne, S., Lee, S., & Bartels, S. A. (2021). Gender-Stratified Analysis of Haitian Perceptions Related to Sexual Abuse and Exploitation Perpetrated by UN Peacekeepers during MINUSTAH. Sexes, 2(2), 216-243. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes2020019