Women’s Knowledge and Awareness of the Effect of Age on Fertility in Kazakhstan

Abstract

:1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

2.3. Data Sources and Measurements

2.4. Study Size

2.5. Quantitative Variables

2.6. Statistical Methods

2.7. Ethics Considerations

3. Results

3.1. Demographic Characteristics

3.2. Behavior and Lifestyles

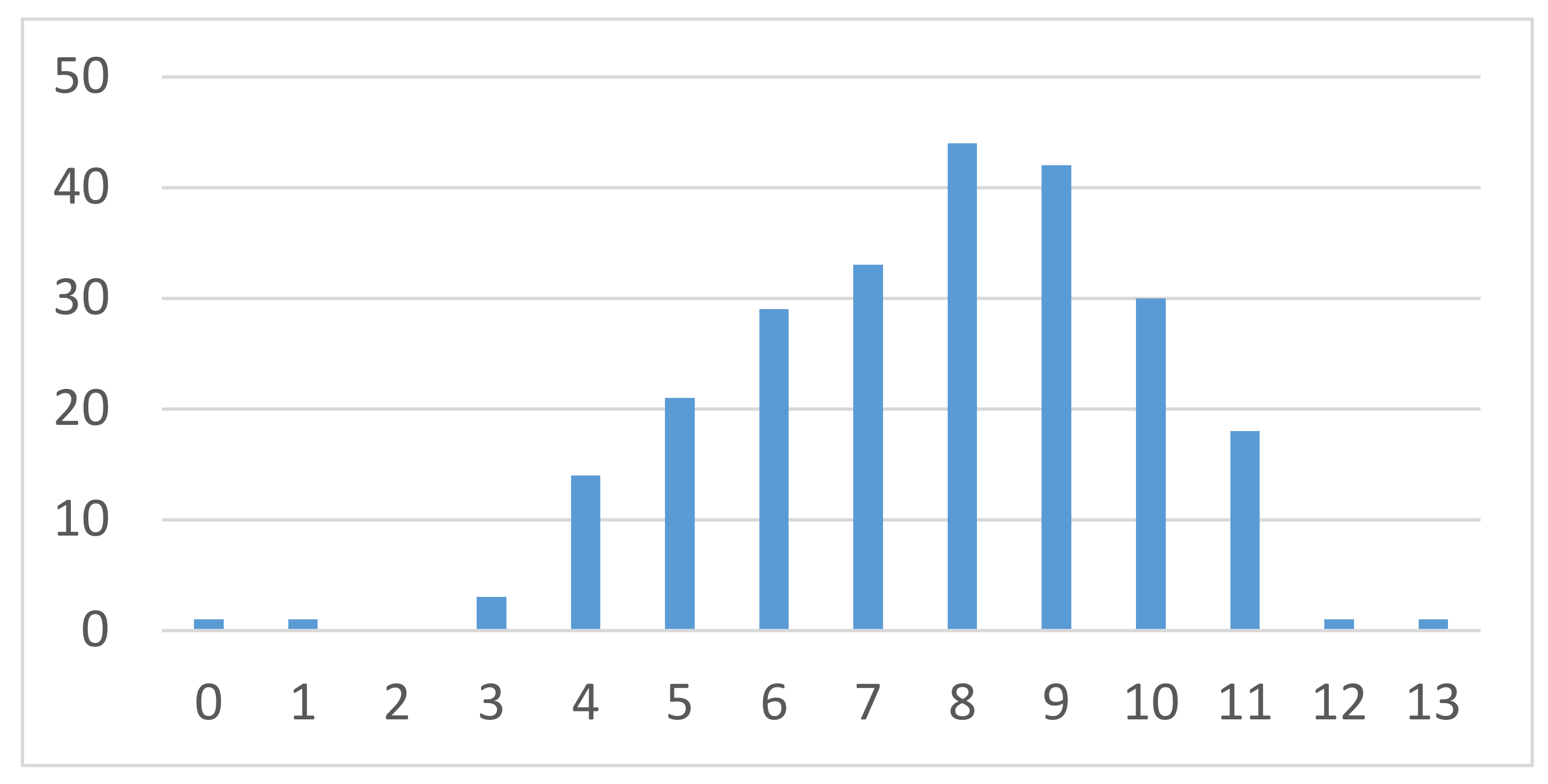

3.3. Knowledge of the Reproductive Consequences of Aging and Reproductive Technologies

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Pedro, J.; Brandão, T.; Schmidt, L.; Costa, M.E.; Martins, M.V. What do people know about fertility? A systematic review on fertility awareness and its associated factors. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2018, 123, 71–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Goldstein, J.R.; Sobotka, T.; Jasilioniene, A. The end of “lowest-low” fertility? Population and development review. Popul. Dev. Rev. 2009, 35, 663–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mills, M.; Rindfuss, R.R.; McDonald, P.; te Velde, E.; ESHRE Reproduction and Society Task Force. Why do people postpone parenthood? Reasons and social policy incentives. Hum. Reprod. Update 2011, 17, 848–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Billari, F.C.; Liefbroer, A.C.; Philipov, D. The postponement of childbearing in Europe: Driving forces and implications. JSTOR 2006, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, M.J. More power to the pill: The impact of contraceptive freedom on women’s life cycle labor supply. Q. J. Econ. 2006, 121, 289–320. [Google Scholar]

- Leridon, H. Can assisted reproduction technology compensate for the natural decline in fertility with age? A model assessment. Hum. Reprod. 2004, 19, 1548–1553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peterson, B.D.; Pirritano, M.; Tucker, L.; Lampic, C. Fertility awareness and parenting attitudes among American male and female undergraduate university students. Hum. Reprod. 2012, 27, 1375–1382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Lampic, C.; Svanberg, A.S.; Karlström, P.; Tydén, T. Fertility awareness, intentions concerning childbearing, and attitudes towards parenthood among female and male academics. Hum. Reprod. 2006, 21, 558–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bretherick, K.L.; Fairbrother, N.; Avila, L.; Harbord, S.H.; Robinson, W.P. Fertility and aging: Do reproductive-aged Canadian women know what they need to know? Fertil. Steril. 2010, 93, 2162–2168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Healthcare and Social Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan. Kazakhstan Family Planning National Framework Program 2017–2021; Ministry of Healthcare and Social Development of the Republic of Kazakhstan: Nur-Sultan, Kazakhstan, 2016.

- Fertility Rate, Total (Births per Woman)—Kazakhstan. Available online: https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.DYN.TFRT.IN?locations=KZ (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Available online: https://kazakhstan.unfpa.org/en/news/unfpa-supports-development-kazakhstan-family-planning-national-framework-program-0 (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Lokshin, V.N.; Khoroshilova, I.G.; Kuandykov, E.U. Personified approach to genetic screening of infertility couples in ART programs. Rep. Natl. Acad. Sci. Repub. Kazakhstan 2018, 1, 37–41. [Google Scholar]

- García, D.; Vassena, R.; Trullenque, M.; Rodríguez, A.; Vernaeve, V. Fertility knowledge and awareness in oocyte donors in Spain. Patient Educ. Couns. 2015, 98, 96–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahey, R.; Gupta, M.; Kandpal, S.; Malhotra, N.; Vanamail, P.; Singh, N.; Kriplani, A. Fertility awareness and knowledge among Indian women attending an infertility clinic: A cross-sectional study. BMC Women’s Health 2018, 18, 177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Evans, A.; de Lacey, S.; Tremellen, K. Australians’ understanding of the decline in fertility with increasing age and attitudes towards ovarian reserve screening. Aust. J. Prim. Health 2018, 24, 428–433, Erratum in 2019, 25, 97. [Google Scholar]

- Gossett, D.R.; Nayak, S.; Bhatt, S.; Bailey, S.C. What do healthy women know about the consequences of delayed childbearing? J. Health Commun. 2013, 18 (Suppl. 1), 118–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buckley, C.; Barrett, J.; Adkins, K. Reproductive health information for young women in Kazakhstan: Disparities in access by channel. J. Health Commun. 2008, 13, 681–697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utepova, G.; Terzic, M.; Bapayeva, G.; Terzic, S. Investigation of understanding the influence of age on fertility in Kazakhstan: Reality the physicians need to face in IVF clinic. Clin. Exp. Obstet. Gynecol. 2019, 46, 461–465. [Google Scholar]

- Agadjanian, V. Post-soviet demographic paradoxes: Ethnic differences in marriage and fertility in Kazakhstan. Sociol. Forum 1999, 14, 425–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Available online: https://tradingeconomics.com/kazakhstan/wages (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Available online: https://www.zakon.kz/5006621-srednyaya-zarplata-v-kazahstane.html) (accessed on 5 May 2020).

- Supiyev, A.; Nurgozhin, T.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Sharman, A.; Marmot, M.; Bobak, M. Levels and distribution of self-rated health in the Kazakh population: Results from the Kazakhstan household health survey 2012. BMC Public Health 2014, 14, 768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sylvest, R.; Koert, E.; Vittrup, I.; Petersen, K.B.; Hvidman, H.W.; Hald, F.; Schmidt, L. Men’s expectations and experiences of fertility awareness assessment and counseling. Acta Obstet. Gynecol. Scand. 2018, 97, 1471–1477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Righarts, A.; Dickson, N.P.; Parkin, L.; Gillett, W.R. Ovulation monitoring and fertility knowledge: Their relationship to fertility experience in a cross-sectional study. Aust. N. Z. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. 2017, 57, 412–419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hawkins, L.K.; Rossi, B.V.; Correia, K.F.; Lipskind, S.T.; Hornstein, M.D.; Missmer, S.A. Perceptions among infertile couples of lifestyle behaviors and in vitro fertilization (IVF) success. J. Assist. Reprod. Genet. 2014, 31, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- O’Brien, Y.M.; Ryan, M.; Martyn, F.; Wingfield, M.B. A retrospective study of the effect of increasing age on success rates of assisted reproductive technology. Int. J. Gynaecol. Obstet. 2017, 138, 42–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kudesia, R.; Chernyak, E.; McAvey, B. Low fertility awareness in United States reproductive-aged women and medical trainees: Creation and validation of the Fertility & Infertility Treatment Knowledge Score (FIT-KS). Fertil. Steril. 2017, 108, 711–717. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kearney, A.L.; White, K.M. Examining the psychosocial determinants of women’s decisions to delay childbearing. Hum. Reprod. 2016, 31, 1776–1787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ford, E.A.; Roman, S.D.; McLaughlin, E.A.; Beckett, E.L.; Sutherland, J.M. The association between reproductive health smartphone applications and fertility knowledge of Australian women. BMC Women’s Health 2000, 20, 45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zillien, N.; Haake, G.; Fröhlich, G.; Bense, T.; Souren, D. Internet use of fertility patients: A systematic review of the literature. J. Reprod. Endokrinol. 2011, 8, 281–287. [Google Scholar]

- Skogsdal, Y.; Fadl, H.; Cao, Y.; Karlsson, J.; Tydén, T. An intervention in contraceptive counseling increased the knowledge about fertility and awareness of preconception health-a randomized controlled trial. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2019, 124, 203–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Fooladi, E.; Weller, C.; Salehi, M.; Abhari, F.R.; Stern, J. Using reproductive life plan-based information in a primary health care center increased Iranian women’s knowledge of fertility, but not their future fertility plan: A randomized, controlled trial. Midwifery 2018, 67, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, K.E.; Case, A. No. 346-Advanced Reproductive Age and Fertility. J. Obstet. Gynaecol. Can. 2017, 39, 685–695. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delbaere, I.; Verbiest, S.; Tydén, T. Knowledge about the impact of age on fertility: A brief review [published online ahead of print, 22 January 2020]. Upsala J. Med. Sci. 2020, 125, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klitzman, R. Impediments to communication and relationships between infertility care providers and patients. BMC Womens Health. 2018, 18, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behboudi-Gandevani, S.; Ziaei, S.; Farahani, F.K.; Jasper, M. The perspectives of iranian women on delayed childbearing: A qualitative study. J. Nurs. Res. 2015, 23, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Behboudi-Gandevani, S.; Ziaei, S.; Khalajabadi-Farahani, F.; Jasper, M. Iranian primigravid women’s awareness of the risks associated with delayed childbearing. Eur. J. Contracept. Reprod. Health Care. 2013, 18, 460–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, G.; Azmat, S.K.; Hameed, W.; Ali, S.; Ishaque, M.; Hussain, W.; Ahmed, A.; Munroe, E. Family planning knowledge, attitudes, and practices among married men and women in rural areas of pakistan: findings from a qualitative need assessment study. Int. J. Reprod. Med. 2015, 2015, 190520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Supiyev, A.; Kossumov, A.; Kassenova, A.; Nurgozhin, T.; Zhumadilov, Z.; Peasey, A.; Bobak, M. Diabetes prevalence, awareness and treatment and their correlates in older persons in urban and rural population in the Astana region, Kazakhstan. Diabetes Res. Clin. Pract. 2016, 112, 6–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

| Socio-Demographic and Clinical Variables | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | ≤35 | 144 | 62.1 |

| 35–37 | 41 | 17.4 | |

| 38–40 | 20 | 8.5 | |

| 41–42 | 12 | 5.1 | |

| 43+ | 16 | 6.8 | |

| Duration of infertility | <3 Years | 66 | 28.0 |

| 3–5 Years | 44 | 18.6 | |

| >5 Years | 115 | 48.7 | |

| Fertility diagnosis | Age factor | 22 | 9.3 |

| Endometriosis | 27 | 11.4 | |

| Male factor | 50 | 21.2 | |

| Ovulatory | 21 | 8.9 | |

| Tubal | 66 | 28.0 | |

| Uterine | 10 | 4.2 | |

| Unexplained | 43 | 18.2 | |

| Education | Elementary | 8 | 3.5 |

| High school | 53 | 23.1 | |

| Bachelor | 123 | 53.7 | |

| Master/Doctorate | 45 | 19.7 | |

| Income (Tenge) | <500,000 | 99 | 43.0 |

| 0.5–1 million | 60 | 26.1 | |

| 1–2 million | 38 | 16.5 | |

| >2 million | 33 | 14.3 | |

| Source of information on fertility and pregnancy | Internet | 107 | 45.3 |

| Television | 6 | 2.5 | |

| Newspapers | 7 | 3.0 | |

| Doctor | 122 | 51.7 | |

| Family | 40 | 16.9 | |

| When started planning pregnancy | <25 | 104 | 45.0 |

| 26–30 | 85 | 36.8 | |

| 30–35 | 28 | 12.1 | |

| >35 | 14 | 6.1 |

| Behavior and Lifestyles Variables | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Exercise | No exercise | 141 | 59.5 |

| <1 h a week | 39 | 16.5 | |

| 1–3 h a week | 47 | 19.8 | |

| >4 h a week | 10 | 4.2 | |

| Yoga | Once a week | 201 | 89.3 |

| 2–6 times a week | 15 | 6.7 | |

| 7 days a week | 9 | 4.0 | |

| Rest after | Normal activity | 81 | 37.2 |

| Limiting strenuous activity and exercise | 106 | 48.6 | |

| Complete bed rest | 31 | 14.2 | |

| Rest before (man) | Normal activity | 26 | 51.0 |

| Limiting strenuous activity and exercise | 22 | 43.1 | |

| Complete bed rest | 3 | 5.9 | |

| Acupuncture | Yes | 12 | 5.2 |

| No | 217 | 94.8 | |

| Weight | Underweight | 21 | 8.9 |

| Normal weight | 150 | 63.6 | |

| Overweight | 57 | 24.2 | |

| Obese | 8 | 3.4 | |

| Stress | Avoiding stress | 140 | 59.3 |

| Having stress | 96 | 40.7 | |

| Attitude | Positive | 212 | 91.4 |

| Negative | 20 | 8.6 | |

| Prayer | Engaging in prayer | 155 | 66.0 |

| No prayer | 80 | 34.0 | |

| Cellular phone | Limited use | 50 | 21.4 |

| Regular use | 184 | 78.6 | |

| Smoking | Not smoking | 211 | 89.4 |

| <5 years | 19 | 8.1 | |

| >5 years | 6 | 2.5 |

| Knowledge Score | Frequency | % | |

|---|---|---|---|

| AMA Score | |||

| Miscarriage is less after 35 common after 35 years old | False | 163 | 69.1 |

| Women are healthier during pregnancy because they are more mature after 35 years old | False | 167 | 70.8 |

| It is harder to get pregnant after 35 years old | Correct | 199 | 84.7 |

| Cesarean section is more common after 35 years old | Correct | 171 | 73.7 |

| Stillbirths/fetal deaths are less common after 35 years old | False | 160 | 69.6 |

| The risk of genetic problems in the baby is higher after 35 years old | Correct | 148 | 63.5 |

| Women have more medical problems during pregnancy after 35 years old | Correct | 176 | 74.6 |

| After infertility treatment, miscarriage rates are higher | Correct | 83 | 35.8 |

| ART Score | |||

| Women have fewer problems like diabetes and high blood pressure after infertility treatment | False | 136 | 59.1 |

| Cesarean section is more common after infertility treatment | Correct | 138 | 59.7 |

| Stillbirths/fetal deaths are more common after infertility treatment | Correct | 65 | 28.3 |

| There are more twins and triplets after infertility treatment | Correct | 159 | 68.8 |

| The risk of genetic problems in the baby is higher after infertility treatment | Correct | 64 | 27.7 |

| Socio-Demographic and Clinical Variables | TKS | AMA | ART | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean | 7.71 | 4.99 | 2.62 | |

| Diagnosis | Age factor | 7.23 | 4.86 | 2.36 |

| Endometriosis | 7.44 | 5.00 | 2.44 | |

| Male factor | 8.24 * | 5.14 | 3.10 * | |

| Ovulatory | 8.90 * | 5.33 | 3.57 * | |

| Tubal | 7.58 | 4.66 | 2.92 * | |

| Uterine | 7.20 | 4.30 | 2.90 | |

| Unexplained | 7.78 | 5.19 | 2.58 | |

| Source of information | Internet | 7.90 | 5.12 | 2.78 |

| Television | 8.17 | 5.88 | 2.33 | |

| Newspapers | 7.71 | 4.57 | 3.14 | |

| Doctor | 7.67 | 5.11 | 2.56 | |

| Family | 7.60 | 5.33 | 2.28 | |

| Age | ≤35 | 7.81 | 5.04 | 2.77 |

| 35–37 | 7.68 | 5.02 | 2.66 | |

| 38–40 | 7.35 | 4.85 | 2.50 | |

| 41–42 | 8.33 | 5.17 | 3.17 | |

| 43+ | 6.94 | 4.50 | 2.44 | |

| Duration of infertility | <3 Years | 7.62 | 4.89 | 2.73 |

| 3–5 Years | 8.07 | 5.18 | 2.89 | |

| >5 Years | 7.64 | 4.99 | 2.65 | |

| Education | Elementary | 8.38 | 6.13 | 2.25 |

| High school | 7.81 | 5.06 | 2.75 | |

| Bachelor | 7.73 | 4.89 | 2.84 | |

| Master/Doctorate | 7.60 | 5.11 | 2.49 | |

| Income (Tenge) | <500,000 | 7.72 | 4.86 | 2.87 |

| 0.5–1 million | 7.33 | 5.00 | 2.33 | |

| 1–2 million | 8.05 | 5.21 | 2.84 | |

| >2 million | 8.09 | 5.12 | 2.97 | |

| Medical history | None | 7.53 | 4.90 | 2.63 |

| One or more IVF | 7.19 | 4.57 | 2.62 | |

| History of gynecologic problems | 8.30 | 5.80 * | 2.50 | |

| Ovarian surgery | 7.94 | 5.50 | 2.44 | |

| When started planning a pregnancy | <25 | 7.61 | 4.95 | 2.66 |

| 26–30 | 7.94 | 5.19 | 2.75 | |

| 30–35 | 7.29 | 4.57 | 2.71 | |

| >35 | 7.71 | 4.93 | 2.79 |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Sarría-Santamera, A.; Bapayeva, G.; Utepova, G.; Krstic, J.; Terzic, S.; Aimagambetova, G.; Shauyen, F.; Terzic, M. Women’s Knowledge and Awareness of the Effect of Age on Fertility in Kazakhstan. Sexes 2020, 1, 60-71. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes1010006

Sarría-Santamera A, Bapayeva G, Utepova G, Krstic J, Terzic S, Aimagambetova G, Shauyen F, Terzic M. Women’s Knowledge and Awareness of the Effect of Age on Fertility in Kazakhstan. Sexes. 2020; 1(1):60-71. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes1010006

Chicago/Turabian StyleSarría-Santamera, Antonio, Gauri Bapayeva, Gulnara Utepova, Jelena Krstic, Sanja Terzic, Gulzhanat Aimagambetova, Fariza Shauyen, and Milan Terzic. 2020. "Women’s Knowledge and Awareness of the Effect of Age on Fertility in Kazakhstan" Sexes 1, no. 1: 60-71. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes1010006

APA StyleSarría-Santamera, A., Bapayeva, G., Utepova, G., Krstic, J., Terzic, S., Aimagambetova, G., Shauyen, F., & Terzic, M. (2020). Women’s Knowledge and Awareness of the Effect of Age on Fertility in Kazakhstan. Sexes, 1(1), 60-71. https://doi.org/10.3390/sexes1010006