1. Introduction

Virginia is currently the fourth-largest seafood producer in the United States [

1]. In 2019, Virginia ranked as the largest producer of hard clams nationwide and oysters along the U.S. Atlantic Coast [

2]. Home to the largest estuary in the United States, the Chesapeake Bay has significant value to Virginia for its ecological, social, historical, cultural, and economic importance. Since the early 1600s, indigenous Powhatan tribes engaged in fishing activities and introduced Chesapeake Bay oysters to English settlers and colonists. As demand for oysters and other Bay products grew, the seafood industry began to organize, necessitating boats to collect them from bars farther out in the rivers and the Bay [

3]. The seafood industry offers many employment opportunities, with over 70 job titles attributed to the sector. Research and development investments in fisheries and aquaculture sectors enhance and diversify job opportunities for various supporting sectors of the Virginia seafood supply chain beyond Virginia [

4].

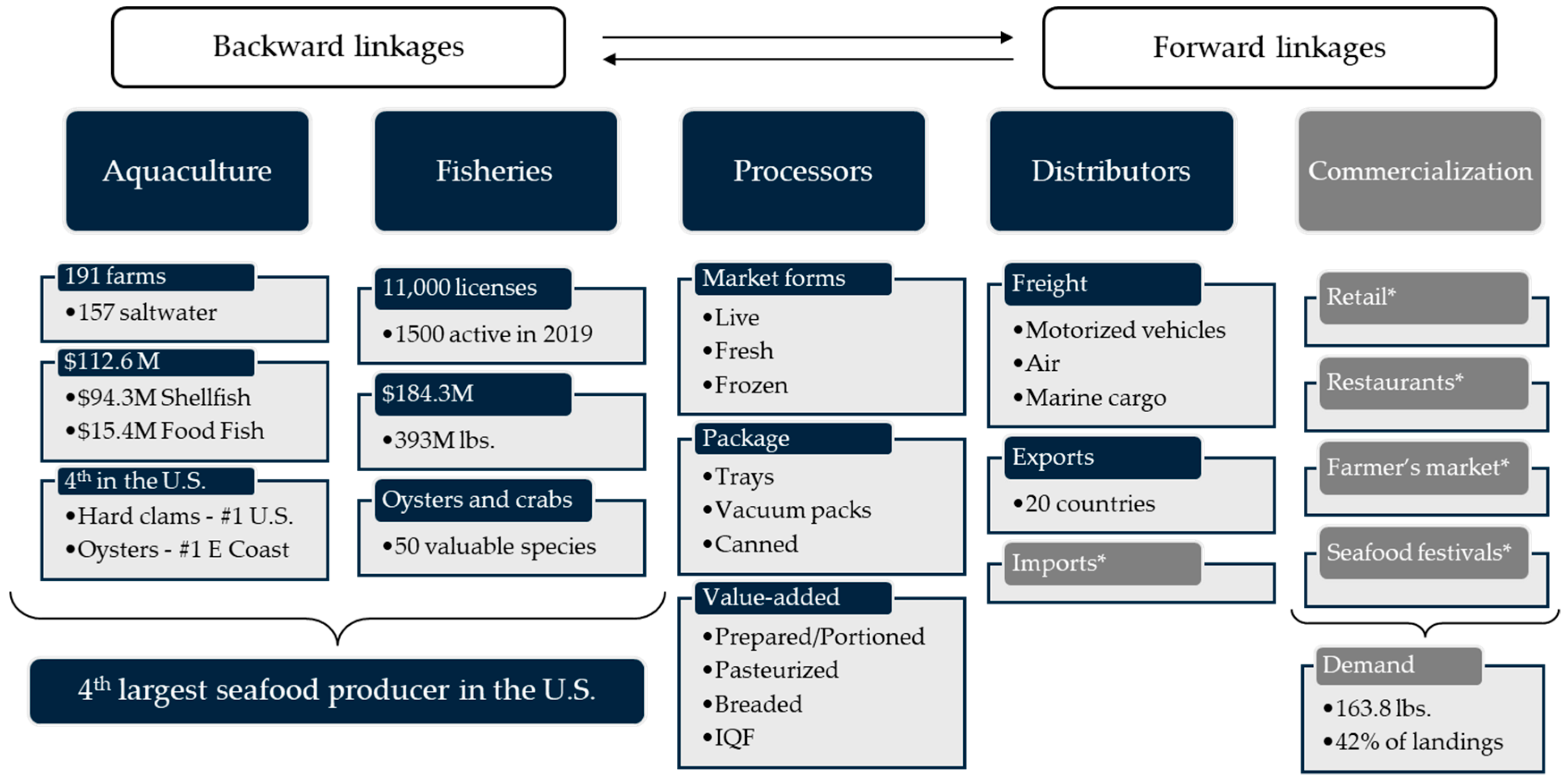

Virginia’s seafood industry comprises multiple supply chain levels, from producers and processors to wholesalers, distributors, retailers, and consumers. A recent comprehensive description of Virginia’s seafood supply chain was produced from information scattered across federal and state agencies that issue permits, monitor catches and production, enforce food safety and sanitary standards, and regulate activities [

5]. Each level of the seafood supply chain performs a distinct function, resulting in different labor, sales, and expenditure patterns. Many businesses engage in commercial activities with each other and rely on additional goods and services provided by other entities within Virginia for their continued success.

Understanding the dynamics of the seafood industry requires a thorough comprehension of economic complexities involving the application of various impact analysis methods. Due to the accessibility of datasets and the availability of modeling software, a common approach for economic impact analysis is the input–output analysis for sector-specific insights [

6,

7]. Some alternative approaches to economic impact analysis include computable general equilibrium (CGE) modeling for a broader view of inter-industry dynamics [

8] and econometric modeling for statistical economic relationship estimation [

9]. Previous studies have reported the economic impact of sectors of the seafood industry for Washington, Oregon, California [

10], Arkansas [

11], Massachusetts [

12], Maine [

13,

14], and North Carolina [

15], and the economic contributions for Florida [

16], Arkansas, Alabama, Mississippi [

7], and western states [

17]. Conceptually, economic impact and economic contribution analyses differ. Economic impact analysis measures the effects of a business creation or expansion event that changes output. On the other hand, economic contribution analysis is an extraction method that measures how an existing industry’s output affects other sectors in a selected region [

18].

Estimates of the economic contributions of Virginia’s commercial seafood and recreational fishing industries were previously estimated in 2005 [

19]. Every year, the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) provides national and state-specific estimates of fisheries’ economic contributions [

20,

21]. However, economic studies often rely on secondary data or theoretical models due to practical challenges in collecting primary data for economic modeling. The difficulty of balancing rigor, resources, and relevance, coupled with the high cost and time-consuming processes, has caused a decline in primary data-based studies across various economic research fields [

22]. Despite the complexity of obtaining primary data, which involves engaging stakeholders and conducting surveys of business entities, the effort yields valuable insights into economic contribution analysis [

23]. The economic contributions of the Virginia seafood industry were estimated for 2019 [

5], providing a foundational understanding for the present study. Building upon those results, this manuscript aims to describe and discuss a methodological framework to assess seafood supply chains and estimate economic contributions in terms of output, jobs, labor income, and tax revenue. This framework also identifies the interconnection between various components of each economic sector and their contributions to the Commonwealth’s overall economy.

2. Materials and Methods

Performing economic contributions analysis with primary data requires careful procedures for data gathering from different sources, assessment of firm-level expenditure data, and the design and implementation of surveys to fill data gaps. These procedures can be accomplished with the following steps.

2.1. Identification of Required Data and Gaps

State agencies overseeing seafood and business activities keep records of the number of commercial licenses and permits held within the state. In Virginia, we obtained data from state agencies to validate the participation of businesses across various tiers of the seafood supply chain. This involved gathering information on the count of aquaculture farms, fishing licenses, distributors, processors, and other relevant entities. Furthermore, we requested detailed data on 2019 harvest landings. All the literature review and secondary data obtained from multiple sources were used to characterize the Virginia seafood supply chain and to produce a supply chain map [

5,

24,

25]. In some cases, secondary data were only available through a formal request and were not publicly accessible online. Additionally, our efforts included identifying any data gaps that are essential for performing an economic contribution analysis of the Virginia seafood industry.

2.2. Data for Direct Effects

The direct economic effects primarily encompass the overall economic output derived from key industries being investigated. Within the Virginia seafood industry context, these direct effects encompass the aggregate sales figures from watermen, aquaculture farms, seafood processors, and distributors. To address watermen’s output in 2019, we utilized the NOAA-published value of USD 184 million [

20] as landings reporting is enforced through reporting programs. Outputs were estimated based on survey responses for the remaining categories within our study. Data for direct effects on labor income include covering income for both proprietors and employees. Our survey specifically inquired about the total payroll cost, encompassing income for both proprietors and employees. To account for economic leakages and focus solely on the economic contributions to the state of Virginia, we requested information on the percentage of sales and employment within the state, excluding any out-of-state transactions. Economic leakages, in this context, refer to imported products (from abroad or out-of-state) purchased by the Virginia seafood businesses as they do not contribute to additional direct effects in Virginia production and are treated as economic spillover [

18].

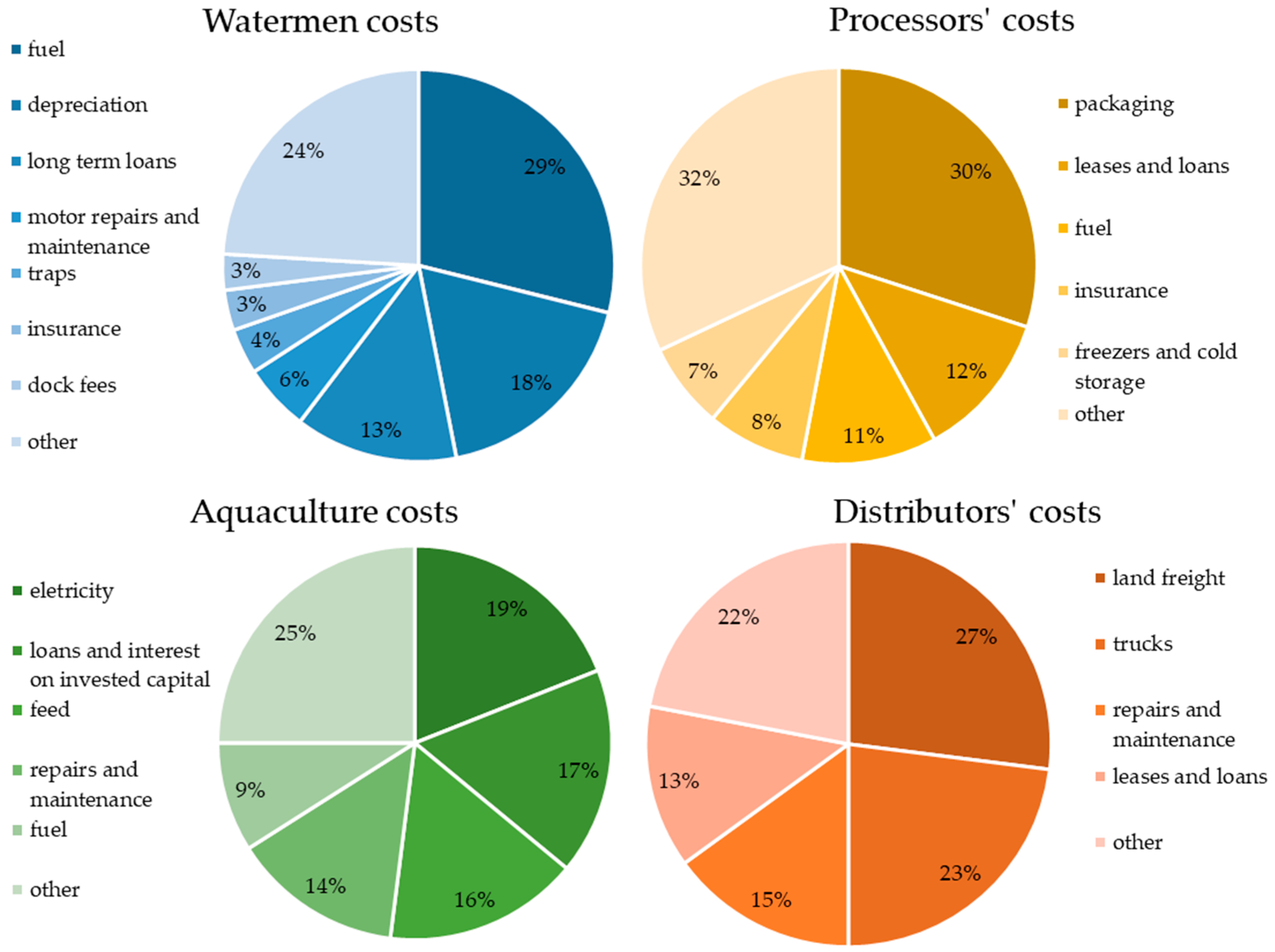

2.3. Expenditure Data

All four levels within the Virginia seafood supply chain considered in this study required various levels of spending information. Specifically, capital investment expenditure data encompassed details on equipment types, sizes, and the total initial purchase of equipment, along with infrastructure construction, pertinent to each level of the seafood supply chain. For each item, we requested information on the initial purchase price and years of useful life, enabling the calculation of annual depreciation values, which were subsequently incorporated into the spending patterns for the year 2019. Moreover, annual operating cost expenditures involved a comprehensive range, covering operating supplies, fishing gear, nets, bait, seed or larvae, fuel, packaging, labels, electricity, and all other associated costs inherent to the operation of each business at each of the supply chain levels studied. To address the impact of economic leakages stemming from imports, each of these costs was attributed to the corresponding percentage of inputs purchased both in-state and out-of-state. We employed an online survey and scheduled interviews to obtain expenditure data for standard seafood business equipment at each supply chain level. Specifically, expenditure patterns were derived from existing enterprise budgets for species raised in the Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS), such as tilapia and trout, as well as in raceways (trout) [

26]. These budgets were subsequently adjusted to align with the spending pattern model designed for aquaculture businesses.

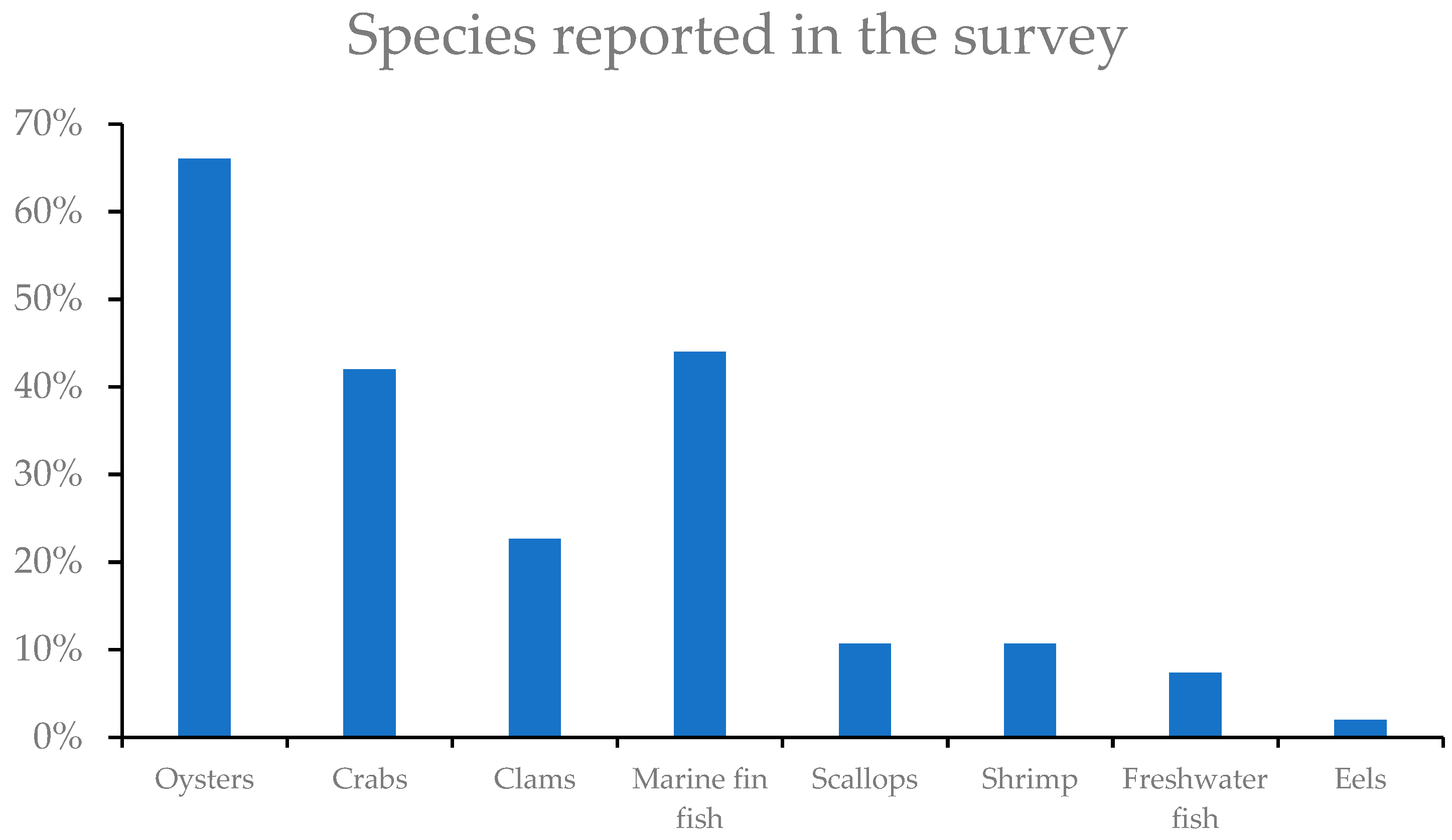

2.4. Survey Design and Data Collection

To establish comprehensive estimates regarding the economic contributions of the Virginia seafood industry, it was imperative to compile data from each tier of the supply chain. Consequently, a Qualtrics online survey was deployed to solicit economic information from watermen, aquaculture farms, processors, and distributors, adhering to the guidelines stipulated by the Virginia Tech Institutional Review Board (IRB #21-433). The survey instrument underwent pretesting and review, with participation from at least one industry representative at each level of the seafood supply chain. Following their insightful feedback, the survey was adjusted to incorporate any missing equipment and infrastructure necessary to accurately represent the data required for developing the economic contribution model. The model for expenditure patterns was constructed based on intermediate inputs, employee compensation, and total output, incorporating the respective local purchase percentages (LPP). This approach ensured a comprehensive and accurate representation of the economic dynamics within the Virginia seafood industry.

2.5. Scope of Data Collection

The survey design aimed to achieve primary data collection for an appropriate state-wide representation of the business entities. This approach ensures that the estimated economic contributions would be both comprehensive and accurate. The design aimed to secure enough observations for each level of the seafood supply chain within the overall dataset, acknowledging the variations in expenditure and revenue patterns across these levels. To facilitate the construction of economic impact models in IMPLAN, each item gleaned from the survey responses underwent summation across individual businesses. The aggregated values were then converted into coefficients, forming the foundation for the subsequent development of the economic impact models.

2.6. Recruitment of Participants and Survey Activities

Contact lists were obtained from the Virginia Marine Resource Commission (VMRC), the Virginia Marine Product Board (VMPB), and the Virginia Department of Agriculture and Consumer Services (VDACS), complemented by additional information from online searches. Our recruitment strategy encompassed email communications, physical mail postage with accompanying flyers, and telephone contact with every eligible entity enlisted on the contact lists. These communications aimed to explain the study, emphasize their voluntary participation and data confidentiality and solicit their involvement. Additionally, in-person meetings were conducted by appointment with individuals, associations, and businesses as part of the recruitment efforts. Every survey response was recorded and coded to safeguard respondent identities and uphold confidentiality. The survey activities and data collection lasted a period of 205 days, from September 2021 to April 2022. Repeated attempts were made to establish contact with members of the target populations throughout this duration. Following the conclusion of survey activities, the collected data were entered into Microsoft Excel templates, for data cleaning and subsequent analysis.

2.7. List Frame and Response Rates

Table 1 provides an overview of the survey list frame development process. Initial contact lists for watermen and aquaculture farms were obtained from the VMRC, utilizing the number of licenses issued in Virginia. To streamline these lists, we specifically targeted active license holders by implementing criteria that identified commercial operations with annual sales equal to or exceeding USD 1000 [

27,

28]. This ensured a focused contact list for commercially active watermen. In 2019, Virginia had 521 issued individual licenses for aquaculture [

29] and 191 active aquaculture farms [

28]. Classifying businesses as processors or distributors posed challenges due to considerable vertical integration. In 2019, Virginia reported a total of 112 seafood operations, comprising 34 processors and 78 distributors [

20]. To address potential nonresponses, our list frame considered the combined total of 112 operations [

20]. However, our study identified 76 processors and 36 distributors, which were determined by estimating the percentage of expenditures dedicated to processing and distribution derived from survey responses and applying it to the vertically integrated entities.

2.8. Accounting for Nonresponses

Values for nonrespondents were estimated by adjusting for the total number of operations identified in each category from the list frame (see

Table 2). Estimations for the expenses of seafood businesses that did not participate were based on the cost structure typical of an average business size. We classified businesses as small, medium, or large, using revenue thresholds of up to USD 1 million, between USD 1 million and USD 9.9 million, and over USD 10 million, respectively.

For vertically integrated seafood businesses, particularly processors and distributors, an additional analysis of their cost structures was conducted. This involved determining the proportional distribution of revenue, employment, and employee compensation. We examined the percentage of expenditures attributed to processing or distribution activities and estimated the number of processors and distributors. The direct effects of these activities were adjusted based on the percentage of sales that remained in Virginia, as reported by survey respondents. Although results from these three activities are encompassed in the overall estimate of the economic contributions of the Virginia seafood industry, they will not be individually presented or discussed to preserve the confidentiality of respondents.

2.9. Economic Contributions Assessment—Theory of Input–output Modeling

An economy can be categorized into basic and nonbasic (service sector) activities [

11]. The basic sector contributes to the inflow of money through trade, while nonbasic activities thrive within the economy as income generated in the basic sector is spent on local goods and services [

11]. In Virginia, the seafood industry operates as a basic sector, producing goods consumed both locally and exported to other areas, generating income and supporting economic activities within the region.

This study used an input–output (IO) approach based on the IMPLAN framework, employing the 2019 IMPLAN database. This database comprises matrices of technical coefficients, accounting for both backward and forward linkages associated with all economic activities in Virginia. IMPLAN models generate linear production functions that establish connections between the outputs of a specific industry and the inputs required for that level of output. The model assumes a linear relationship between the total output q from sector i, expressed within a generalized IO model framework as the sum of goods and services sold to other sectors z

ij and to the final demand sector f

i. This function can be expressed as follows:

The variable z

ij, representing intermediate sales to all sectors j, is a distinctive linear function derived from the output of q

j, which pertains to the output of intermediate industries. When this function is divided by q

j, it yields a matrix containing the technical coefficients of the input–output model. Both i and j can assume values ranging from 1 to N. The inversion of this matrix facilitates the representation of the input–output model:

In Equation (2), I represents an identity matrix, A stands for a technical coefficient matrix typically derived by dividing z

ij by q

j, and m

ij represents the supply chain interaction coefficients in the multiplier matrix M. However, in this study, we obtained A by dividing z

ij by z

j because detailed information was available only for commodity purchases, distinct from labor costs and taxes [

18]. F denotes the final demand matrix for all sectors in the given economy. Therefore, the output multiplier for each sector j can be derived by dividing M by I. These multipliers encapsulate the economic effects, specifically the rates of change, stemming from the fundamental production level. They enable the estimation of direct, indirect, and induced effects resulting from spending activities within the Virginia seafood industry at each level of the supply chain. Similarly, analogous to the output multiplier, multipliers for employment, labor income, and value addition signify the rates of change in these variables within the economy due to their economic impact on basic-level production [

7]. These multipliers offer an understanding of the ripple effects associated with economic activities in the Virginia seafood industry across different economic indicators.

The input–output model gains further depth with the integration of a social accounting matrix (SAM), providing a more comprehensive depiction of economic activities within the specified study area [

11]. The SAM incorporates transactions among various participants in the economy, offering a better understanding of the mechanisms driving household income generation [

11]. The IMPLAN online system facilitates the seamless combination of the input–output model and social accounting matrix, creating a user-friendly and highly adaptable approach to estimating the Virginia seafood industry’s direct, indirect, and induced economic impacts.

Based on the definitions proposed by Kaliba and Engle [

11], the direct effects are those accumulated within the industry under investigation, such as direct employment or sales by seafood firms. Indirect effects manifest in related industries through interlinked sectors; for instance, fuel purchases by watermen influence the broader petroleum refining and production industry. Induced effects encapsulate changes in household expenditures resulting from income changes in related sectors. Examples include salaries paid that lead to additional economic activity through the purchase of homes, utilities, groceries, and other goods and services.

2.10. Analysis-by-Parts

County-level IMPLAN datasets specific to Virginia for the year 2019 were acquired through a 1-year access subscription from The IMPLAN Group’s cloud-based system [

18]. These datasets cover various industries, including commercial fishing (industry 17), seafood product preparation and packaging (industry 92), and truck transportation (industry 417) [

18]. Aquaculture is not allocated to a dedicated sector; instead, it is grouped under animal production (industry 14), excluding cattle, poultry, and eggs. Furthermore, industry 417 (truck transportation) is not exclusively associated with seafood distribution. While it is feasible to assign watermen, processors, and distributors to industries 17, 92, and 417 and attribute aquaculture to industry 14 to enhance the accuracy of estimating the impacts of the Virginia seafood industry, we adopted an analysis-by-parts (ABP) approach. The ABP approach allows for separating the effects of an industry into its components, including budget expenditures and income. This affords greater flexibility and customization of the model by enabling the specification of commodity inputs, defining a proportion of local labor income, determining local purchases, and utilizing IMPLAN’s spending patterns [

7]. To effectively employ this model, it was necessary to first define the direct effects of the Virginia seafood industry. As detailed earlier, these direct effects were derived from respondent data and adjusted for nonresponse. Labor income per worker information from the survey and IMPLAN’s industry averages data for taxes on production and imports (TOPI) and other property income (OPI) were employed to calculate the direct effects of the value added.

An industry spending pattern was developed to calculate the indirect effects reflecting expenditures within the seafood business at each level (watermen, aquaculture farmers, processors, and distributors). Coefficients for these patterns were determined by dividing the cost of a specific input by the total costs of all intermediate inputs for each level. These coefficients were then assigned to the corresponding NAICS (North American Industry Classification System) sector codes and their respective IMPLAN commodity codes. A unique spending pattern was created for each activity: watermen, aquaculture farmers, processors, and distributors. The expenses related to seafood purchases from processors and distributors were excluded from the spending patterns. Since the seafood produced by watermen and aquaculture farmers constitutes their revenue, attributing these values as expenses for processors and distributors causes double counting of the dollars in the estimates. The analysis-by-parts (ABP) approach was instrumental in delineating the economic contribution of all levels of the seafood supply chain. This approach captures the complete revenue generation at each supply chain level without double-counting the sales, recognizing it only once as ex-gate revenue and not as an expense in the respective forward linkages [

7]. To estimate the induced effect of the seafood industry in Virginia, a labor income value was incorporated into the model to account for employee compensation. Once developed, the economic impact model scenarios were executed without any scale modification. The IMPLAN online system provides a user-friendly and highly adaptable means of integrating the input–output model and social accounting matrix [

7,

11]. This integration allows for the generation of estimates encompassing the Virginia seafood industry’s direct, indirect, and induced economic contributions.

2.11. Study Area Characteristics

As a “Mid-Atlantic” state, Virginia shares borders with Maryland, the District of Columbia, North Carolina, Tennessee, Kentucky, West Virginia, and the Atlantic Ocean. With a population exceeding eight million residents, Virginia boasted a gross domestic product of USD 561 billion in 2019, generated by 508 diverse industries that collectively sustain over 5.3 million jobs, USD 504.4 billion in personal income, and a total output of USD 929 billion [

18,

30]. The majority of seafood production occurs in Eastern Virginia, which encompasses five distinctive regions: the Northern Neck, the Middle Peninsula, the Virginia Peninsula, Southern Virginia, and the Eastern Shore (

Figure 1). These regions are demarcated by the rivers Potomac, Rappahannock, York, and James, all of which interconnect with the Chesapeake Bay and the Atlantic Ocean.

4. Discussion

Obtaining primary data by surveying industry stakeholders requires a specific set of interpersonal skills for the investigator. While the choice to employ online surveys offers advantages such as cost reduction, increased reach, minimized transcription errors, and streamlined analysis processes, it typically results in a response rate that is, on average, 12% lower compared with other survey modes [

33]. Despite the limitations in response rates from online surveys, the industry’s participation and engagement will increase as more interactions are made and trust is built. Stakeholders will be more likely to share their data when certain levels of trust, likeability, and the benefits of participating in the study are well explained and understood. Specific activities that contributed to building trust, likeability, and understanding of the project’s benefits to the industry include pretesting the survey questions with selected stakeholders, scheduling personal meetings, attending association events, and explaining the reasons why stakeholders should share their information in the survey. In addition, data management and confidentiality protocols need to be clearly stated, as well as strategies to avoid any exposure of identifiable information, such as details of contributions from a small area where a company may have dominance. These are helpful steps in building trust and a good reputation that will be carried on in the industry, as the investigator will encourage stakeholders to request participation from others.

Even with these steps, along with a strong campaign to recruit participants, participation was voluntary. Despite repeated efforts to contact entities on the list frame, increasing participation in the survey activities was very difficult. Some reasons for refusing to participate in the study included the survey length, the type of information requested, and fear of the study results being used to create new regulations. The latter was a common complaint based on past experiences with research studies that led to stricter regulations on fishing activities. According to the McLaughlin–Sherouse List [

34], the median industries have 1130 restrictions ranked by the industry regulation index [

35]. Fishing is the seventh most regulated industry in the United States with 13,218 restrictions, outpacing oil and gas extraction, pharmaceutical and medicine manufacturing, and deep sea, coastal, and Great Lakes water transportation [

34].

The response rate for farms in this study is consistent with response rates observed in other studies focusing on seafood and aquaculture in the United States. For instance, a study conducted in 2019 to assess the economic impact of the wild-caught fishing industry in North Carolina obtained a response rate of 22.7% from commercial seafood harvesters where participants were incentivized with a USD 50 Amazon gift card for each completed survey [

15]. Similarly, a study conducted in 2019 to evaluate the economic benefits of Maryland shellfish aquaculture reported a response rate of 5% for wholesale/distributors and 33% for hatcheries and farms [

36]. In other regions, the Massachusetts shellfish industry reported a response rate of 35% [

12], while Maine achieved a response rate of 66.4% [

13]. Survey fatigue and refusals were inherent challenges that researchers encountered in every study. Therefore, it is crucial to recognize that this analysis has certain limitations. The primary limitation lies in the response rate, which may result in underestimated activity expenditures. Evidence suggesting that the results present conservative estimates is apparent when comparing values from survey results to IMPLAN industry averages of income per worker. The IMPLAN database presents higher average income values per worker for fisheries, seafood processing, and truck transportation, approximately 2, 2.3, and 4.5 times higher, respectively, than the values obtained in the present study (

Table 10). However, it should be noted that since aquaculture is not disaggregated from IMPLAN industry 14 (animal production, except cattle, poultry, and eggs), the labor income per worker value attributed to the model from our primary data is 15 times higher than the IMPLAN model. This emphasizes the importance of customizing expenditures and adopting an analysis-by-parts approach to better represent the seafood industry.

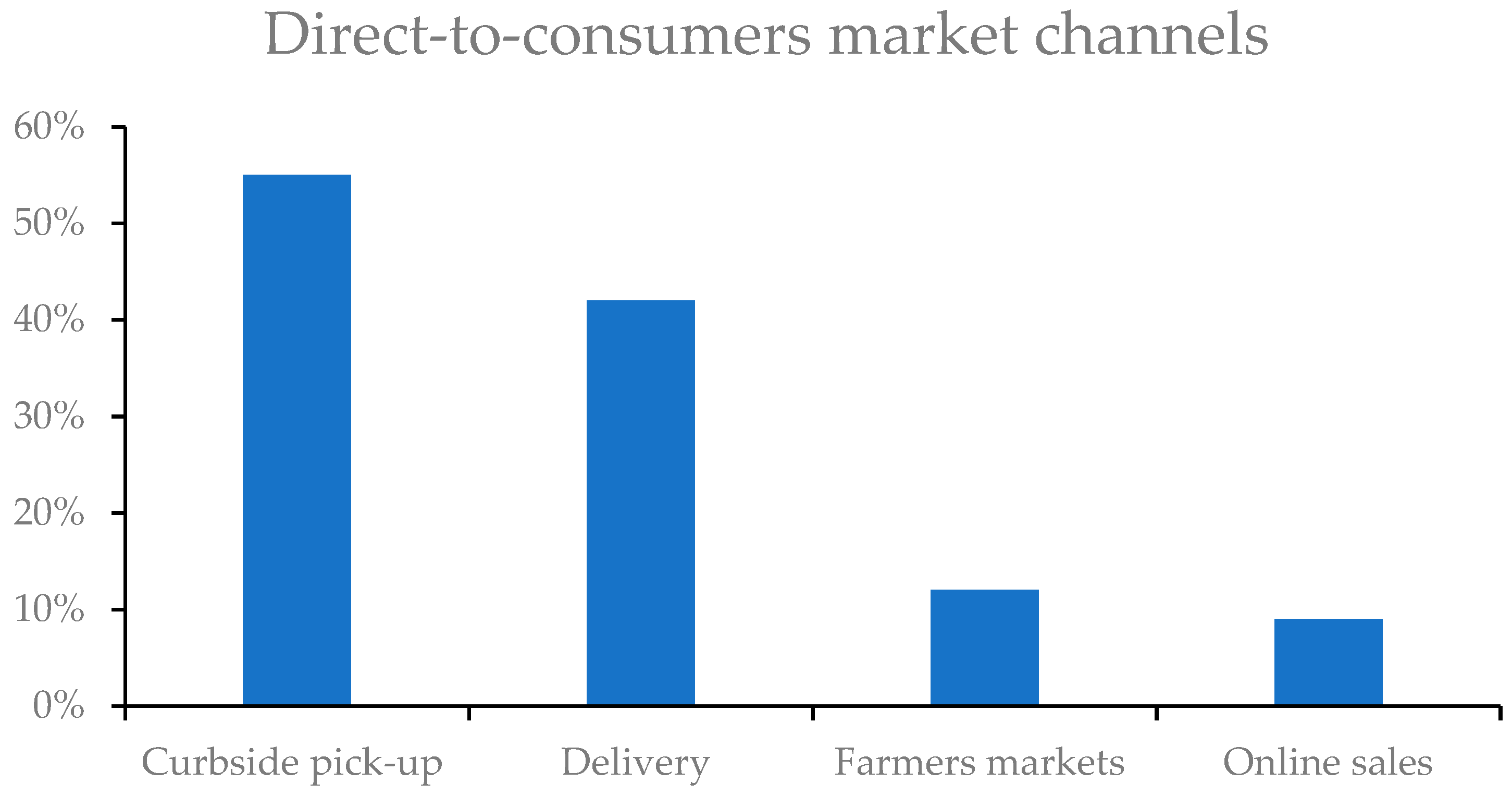

The results presented offer a snapshot of the Virginia seafood industry in 2019, just before the onset of the global COVID-19 pandemic. It is important to note that the pandemic significantly affected the seafood industry, as demonstrated by a national COVID-19 impact assessment conducted by VSAREC and Ohio State University [

37]. The assessment revealed that the U.S. mollusk aquaculture sector was particularly hard hit, with 97% of shellfish respondents reporting negative impacts. The imposition of non-essential business shutdown mandates resulted in the loss of sales and market opportunities for seafood producers. These economic repercussions created ripple effects throughout the seafood supply chain, leading to various secondary effects and impacts on labor, operations, and future supply [

37]. Although COVID-19 was not originally part of this study’s scope, the results can serve as a valuable benchmark for policymakers and stakeholders aiming to increase preparedness for crises and enhance the resilience of the seafood industry to safeguard its essential existence in the face of future challenges.

The economic contributions estimated in this study were confined to activities and expenditures within Virginia and did not capture expenditures and activities outside the state. For example, the respective portion of the equipment produced or purchased outside of Virginia would not have contributed to the economic impact in Virginia. There were also equipment, employment, and sales records that extended beyond the study area. These activities have economic impacts outside Virginia and were not accounted for in the estimate of the economic impact within Virginia. In economic contribution analysis, this concept is called “leakage”. Leakage of impacts is always present, given that goods and services are not always fully contained within the relevant study area. Any portion of goods or services manufactured, purchased, or sold elsewhere contributes to the leakage of impacts from the study area [

7]. The leakages were accounted for in the models by assigning the values of local purchase percentages (LPP) obtained through the survey to each event value of the spending patterns in IMPLAN. Editing LPPs indicates the specific portion of the event value that affects the local region and should be applied to the model multipliers as leakages do not create any local effect [

18]. Therefore, setting appropriate LPPs increases the accuracy of the economic effect estimates.

The economic contributions of the Virginia seafood industry account for 0.13% of employment, 0.03% of labor income, 0.08% of the value added (or GDP), and 0.12% of total output. These contributions may seem small, but they represent a significant source of revenue and jobs for coastal communities. For perspective, the economic impact of agriculture industries in Virginia in 2021, including segments of aquaculture, accounted for 12% of the state’s total output, with a multiplier of 1.93 [

38]. When comparing the results of this study with other industries or studies, it is essential to exercise caution due to differences in methodologies and data management practices. To facilitate accurate comparisons, we recommend conducting future economic contribution analysis utilizing primary data and the framework presented by this paper and allowing these results to serve as a benchmark. Therefore, we strongly advise careful consideration when drawing comparisons across different years, industries, and methods to ensure accurate and meaningful insights.

It is acknowledged that direct employment in the Virginia seafood industry may be underestimated in this study. According to VMRC data, there were 11,638 individuals holding commercial fishing permits and 521 individuals holding aquaculture permits in 2019. Additionally, some oyster farmers mentioned that it is common for homeowners to obtain licenses and lease aquaculture grounds, leading to aquaculture activities occurring near their waterfront properties. To address this, direct employment was estimated from survey responses, accounting for nonresponse based on active licenses that reported production for watermen and using the USDA census of aquaculture to establish the number of active farms. Based on the data provided by respondents, a direct employment effect of 6050 employees was estimated. Comparatively, a new study in Maine estimated an economic contribution of USD 3.2B supporting 33,300 jobs using available secondary data [

14]. While there is a growing trend in using secondary data in economic studies, it presents limitations compared with primary data [

22]. The challenges of conducting economic contribution studies through primary data collection are not limited to time constraints and financial resources. All the steps taken in this present study aimed to ensure data quality and accuracy in the survey design, with a focus on mitigating biases and errors. It is crucial to verify the status of active or inactive producers before estimating the economic contribution of an industry. In some cases, available secondary data may not accurately represent the current state of an industry and may result in misestimating its impacts. Therefore, gathering primary data from as many active participants as possible ensures accurate economic contribution estimations. The present study verified that 13% of the fishing license holders were active, reporting production of at least USD 1000 in 2019. Without verifying the status of license holders, the analysis based on the total number of fishing licenses would be misrepresented.

Furthermore, it is important to note that this study did not aim to capture the impacts of seafood retail or restaurant sales in Virginia. As the economic effects of seafood retail and restaurants remain unknown in Virginia, studying these important sectors would provide a complete and comprehensive estimate of the economic contributions of the seafood industry to the state’s economy. NOAA estimated that the economic impact for the Virginia commercial fishing industry, including wild harvesting, processing, retail, wholesale, and imports, accounted for 23,523 jobs, USD 3.2 billion in sales, USD 803 million in income, and USD 1.2 billion in value-added effects [

20]. However, aquaculture was not included in the data, and the estimation of imports was based on a common multiplier applied throughout all levels of the supply chain. It is worth noting that the methodology used by NOAA differed from the analysis-by-parts approach utilized in the estimates for Virginia. This study offers values derived from primary data gathered directly from industry sources, which remains pertinent despite the assumption that these economic values are conservative and likely underestimated. Through successful survey activities, comprehensive data were obtained to conduct an economic contribution analysis for the Virginia seafood industry. The findings were aggregated across each level of the supply chain for the entirety of Virginia and were not delineated by county or region to safeguard the confidentiality of respondents.

5. Conclusions

Obtaining primary data through surveying industry stakeholders relies heavily on the investigator’s interpersonal skills to build trust and clearly explain the benefits the study can provide to the industry, including its potential to provide insights to guide policy decisions. This study’s methods provide a comprehensive framework for assessing seafood supply chains using secondary data and estimating economic contributions in seafood industries through primary data. Researchers can generate comparable results by applying this framework in future studies, enabling accurate data comparison and benchmarking against our findings. The estimated total economic contributions of the Virginia seafood industry in 2019 were USD 1.1 billion. The Virginia seafood industry provides valuable employment opportunities for watermen and citizens in coastal areas of the Commonwealth, benefiting 7187 people, with a direct effect of 6050 jobs, an indirect effect of 523 jobs, and an induced effect of 614 jobs. Moreover, the influence of the Virginia seafood industry extends beyond its immediate economic sector, supporting various other industries. Direct expenditures by seafood businesses contribute to supporting polystyrene foam product manufacturing, boat building, sporting and athletic goods manufacturing, as well as commercial and industrial machinery, equipment repair, and maintenance. Additionally, wages and salaries paid to employees across the seafood supply chain have a multiplier effect on Virginia’s economy. This economic ripple effect benefits sectors such as nondepository credit intermediation, owner-occupied dwellings, and real estate. In addition, future research capturing the economic contributions from seafood sales in restaurants and retail stores will provide a complete understanding of the seafood industry’s role in shaping the state’s economic landscape.