Métiers and Socioeconomics of the Hellenic Small-Scale Sea Cucumber Fishery (Eastern Mediterranean Sea)

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

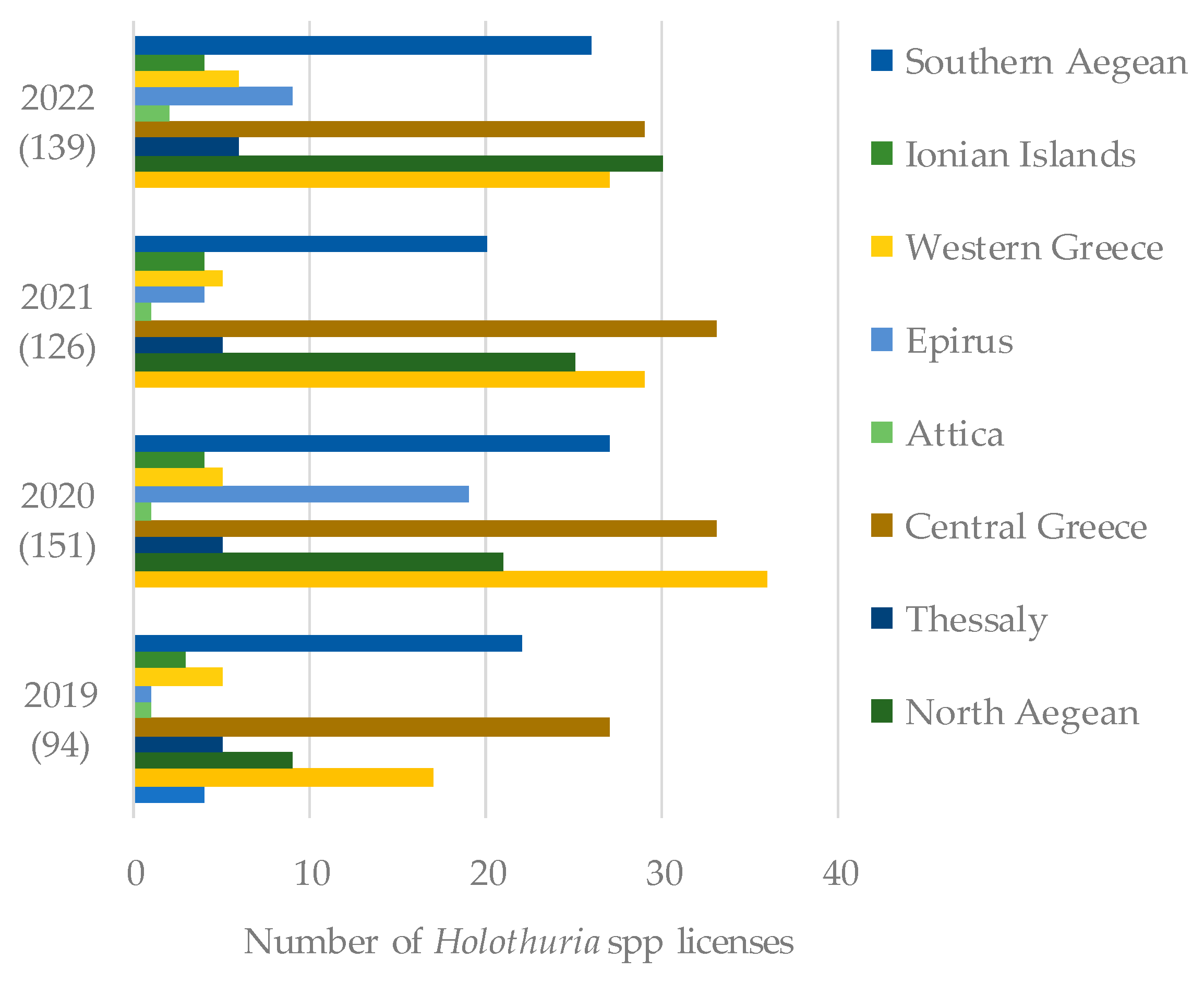

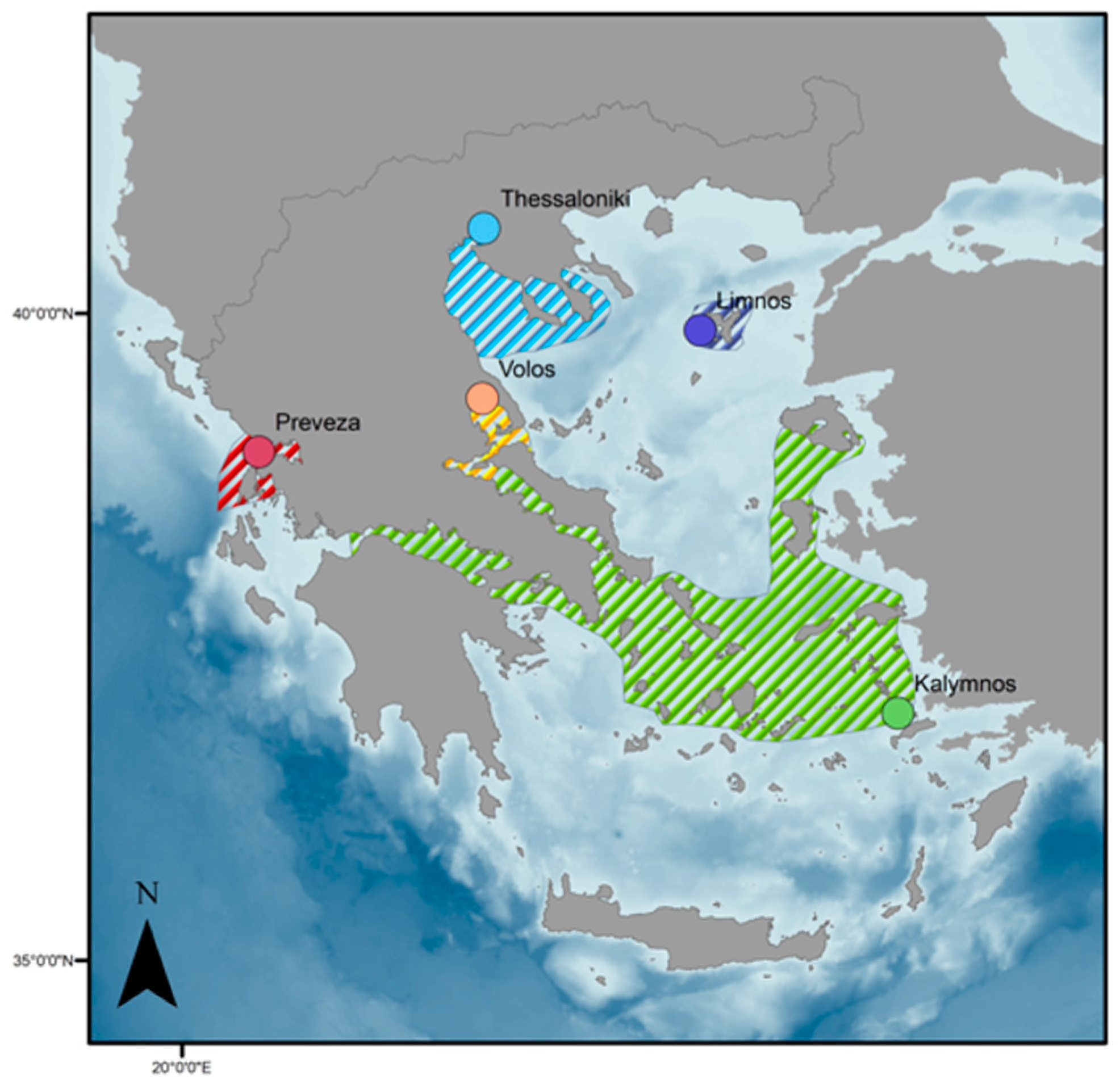

3.1. The Fishing Fleet

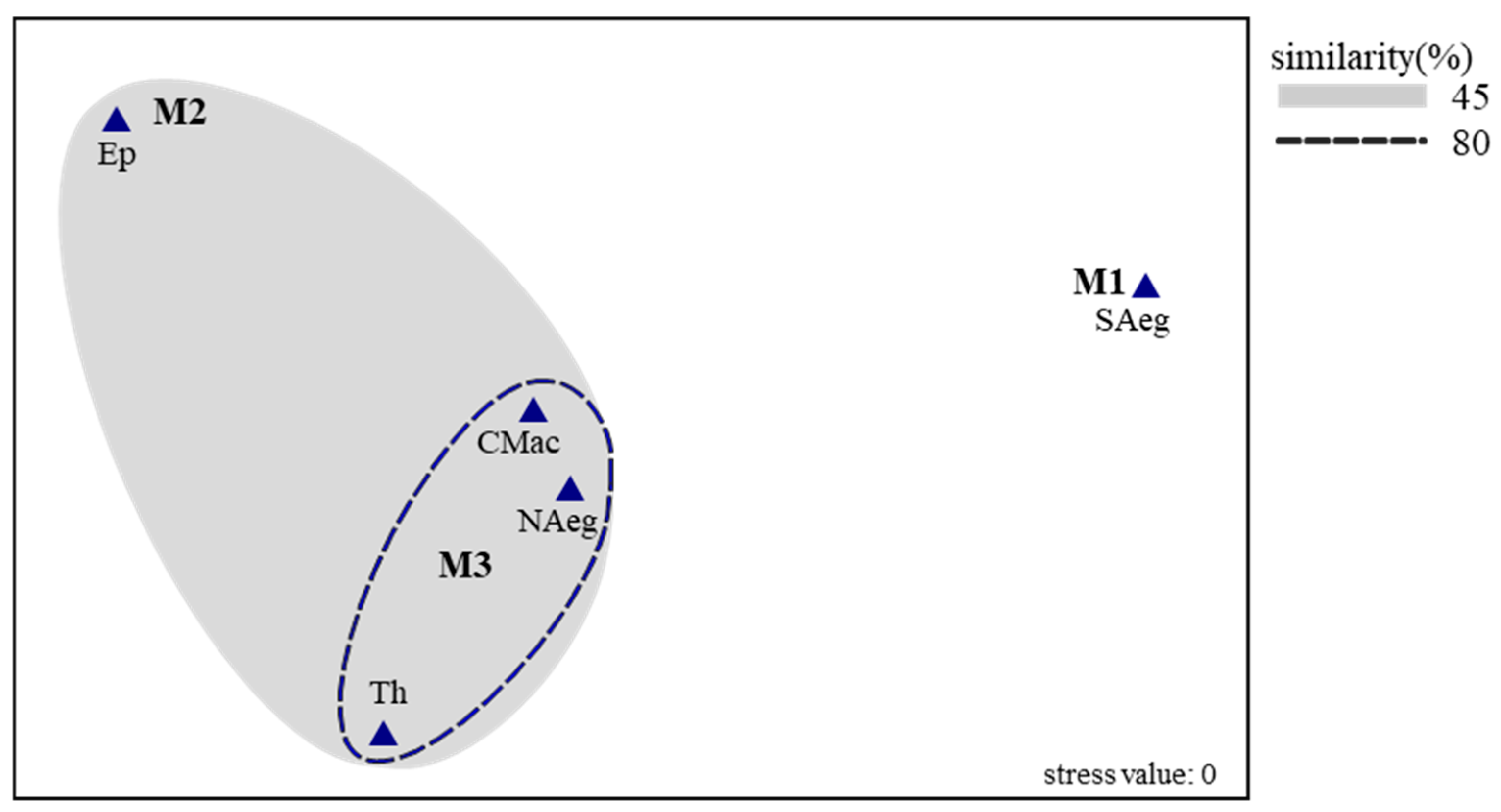

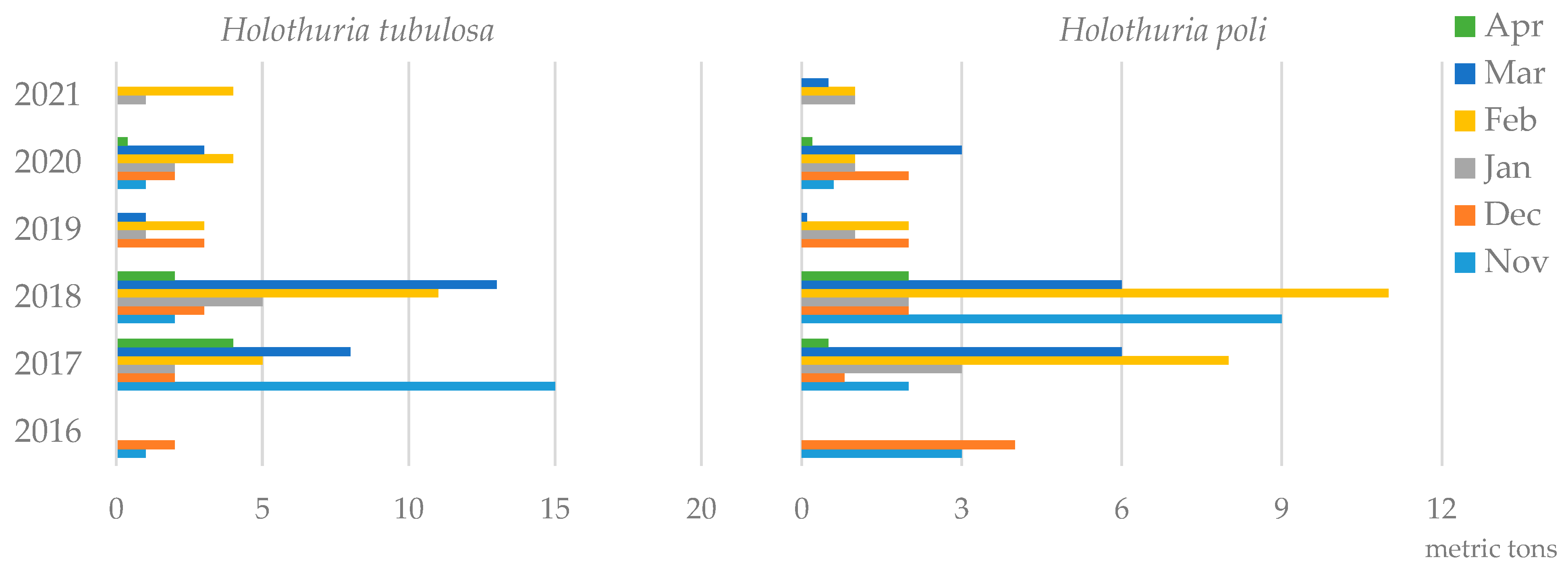

3.2. Métiers, Fishing Practices, and Vessel Expenses

3.3. Socioeconomic Data

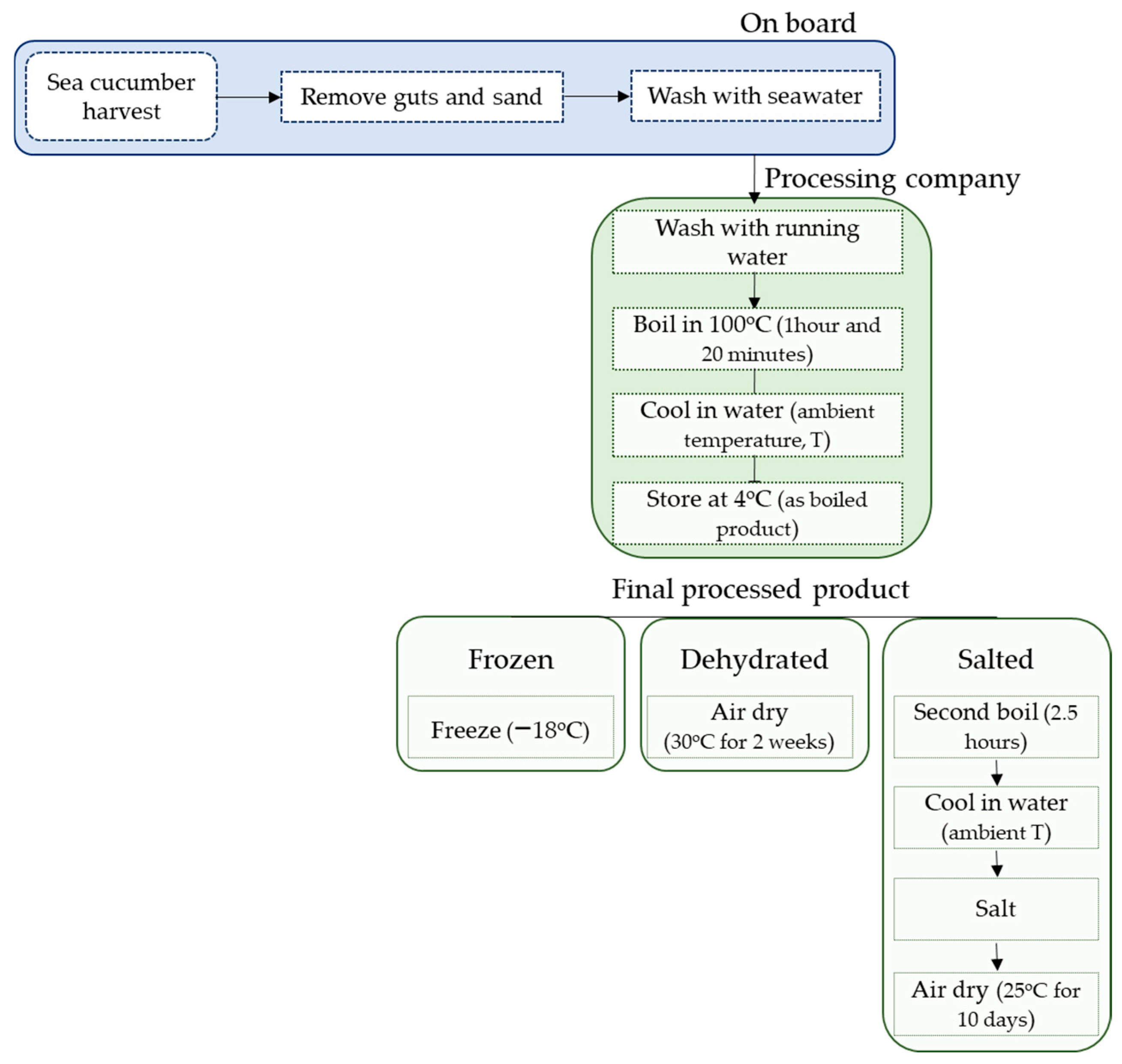

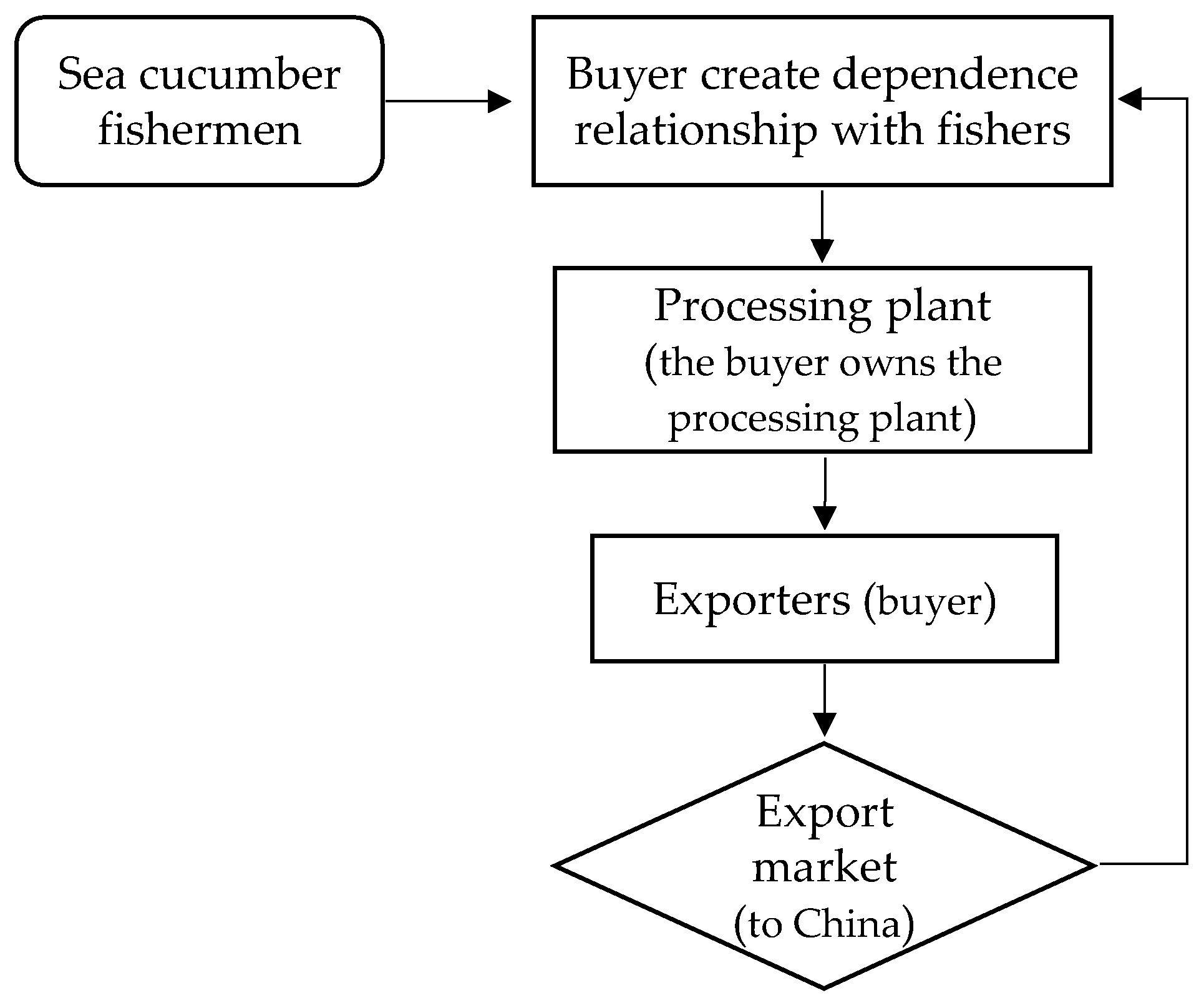

3.4. Processing and Marketing

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Grafton, R.Q.; Kompas, T.; McLoughlin, R.; Rayns, N. Benchmarking for fisheries governance. Mar. Pol. 2007, 31, 470–479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schuhbauer, A.; Sumaila, U.R. Economic viability and small-scale fisheries—A review. Ecol. Econ. 2016, 124, 69–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanatos, E.; Somarakis, S.; Tserpes, G.; Koutsikopoulos, C. Identifying and classifying small-scale fisheries métiers in the Mediterranean: A case study in the Patraikos Gulf, Greece. Fish. Res. 2006, 81, 158–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Romeo, T.; Consoli, P.; Scotti, G.; Andaloro, F. Characterization of the artisanal fishery and its socio-economic aspects in the central Mediterranean Sea (Aeolian Islands, Italy). Fish. Res. 2010, 102, 87–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battaglia, P.; Andaloro, F.; Consoli, P.; Peda, C.; Raicevish, S.; Spagnolo, M.; Romeo, T. Baseline data to characterize and manage the small-scale fishery (SSF) an oncoming Marine Protected Area (Cape Milazzo, Italy) in the western Mediterranean Sea. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2017, 148, 231–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fulton, E.A.; Link, J.S.; Kaplan, I.C.; Savina-Rolland, M.; Johnson, P.L.; Ainsworth, C.; Horne, P.; Gorton, R.; Gamble, R.J.; Smith, A.D.M.; et al. Lessons in modelling and management of marine ecosystems: The Atlantis experience. Fish Fish. 2011, 12, 171–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quetglas, A.; Merino, G.; Ordines, F.; Guijarro, B.; Garau, A.; Antoni, M.G.; Oliver, P.; Massutí, E. Assessment and management of western Mediterranean small-scale fisheries. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2016, 133, 95–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palmer, M.; Tolosa, B.; Grau, M.A.; del Mar Gil, M.; Obregon, C.; Morales-Nin, B. Combining sale records of landings and fishers knowledge for predicting métiers in a small-scale, multi-gear, multispecies fishery. Fish. Res. 2017, 195, 59–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roditi, K.; Vafidis, D. Small-scale fisheries in the south Aegean Sea: Métiers and associated economics. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2022, 224, 106185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roditi, K.; Antoniadou, C.; Matsiori, S.; Halkos, G.; Vafidis, D. Longline métiers and associated economic profiles in eastern Mediterranean fisheries: The case study of Kalymnos Island (South Aegean Sea). Ocean Coast. Manag. 2020, 195, 105275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cooke, S.J.; Venturelli, P.A.; Twardek, W.M.; Lennox, R.J.; Brownscombe, J.W.; Skov, C.; Hyder, K.; Suski, C.D.; Diggles, B.K.; Arlinghaus, R.; et al. Technological innovations in the recreational fishing sector: Implications for fisheries management and policy. Rev. Fish Biol. Fish. 2021, 31, 253–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toral-Granda, V.; Lovatelli, A.; Vasconcellos, M. Sea Cucumbers: A Global Review of Fisheries and Trade; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; No. 516; pp. 1–317. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, K.; Purcell, S.; Bell, J.; Hair, C. Sea Cucumber Fisheries: A Manager’s Toolbox; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research (ACIAR) Monograph: Canberra, Australia, 2008; No. 135; pp. 1–32.

- Conand, C.; Claereboudt, M.; Dissayanake, C.; Ebrahim, A.; Fernando, S.; Godvinden, R.; Lavitra, T.; Léopold, M.; Mmbaga, T.; Mulochau, T.; et al. Review of fisheries and management of sea cucumbers in the Indian Ocean. WIO J. Mar. Sci. 2022, 21, 125–148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González-Wangüemert, M.; Domínguez-Godino, J.; Cánovas, F. The fast development of sea cucumber fisheries in the Mediterranean and NE Atlantic waters: From a new marine resource to its over-exploitation. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2018, 151, 165–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, W.S.; Williamson, H.D.; Ngaluafe, P. Chinese market prices of beche-de-mer: Implications for fisheries and aquaculture. Mar. Pol. 2018, 45, 240–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafidis, D.; Antoniadou, C. Holothurian fisheries in the Hellenic Seas: Seeking for sustainability. Sustainability 2023, 15, 9799. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochiewo, J.; Torre-Castro, M.; Muthama, C.; Munyi, F.; Nthuta, J.M. Socio-economic features of sea cucumber fisheries in southern coast of Kenya. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2010, 53, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W.; Mercier, A.; Conand, C.; Hamel, J.-F.; Toral-Granda, M.V.; Lovatelli, A.; Uthicke, S. Sea cucumber fisheries: Global analysis of stocks, management measures and drivers of overfishing. Fish Fish. 2013, 14, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazanidis, G.; Antoniadou, C.; Lolas, A.; Neofitou, N.; Vafidis, D.; Chintiroglou, C.; Neofitou, C. Population dynamics and reproduction of Holothuria tubulosa (Holothuroidea: Echinodermata) in the Aegean Sea. J. Mar. Biol. Assoc. 2010, 90, 895–901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Antoniadou, C.; Vafidis, D. Population structure of the traditionally exploited holothurian Holothuria tubulosa in the south Aegean Sea. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2011, 52, 171–175. [Google Scholar]

- González-Wangüemert, M.; Aydin, M.; Conand, C. Assessment of sea cucumber populations from the Aegean Sea (Turkey): First insights to sustainable management of new fisheries. Ocean Coast. Manag. 2014, 92, 87–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dereli, H.; Aydın, M. Sea cucumber fishery in Turkey: Management regulations and their efficiency. Reg. Stud. Mar. Sci. 2021, 41, 101551. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinch, J.P.; Purcell, S.W.; Uthicke, S.; Friedman, K. Population status, fisheries and trade of sea cucumbers in the Western Central Pacific. In Sea Cucumbers: A Global Review of Fisheries and Trade; Toral-Granda, V., Lovatelli, A., Vasconcellos, M., Eds.; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2008; No. 516; pp. 7–55. [Google Scholar]

- Allison, E.H.; Ratner, B.D.; Asgard, B.; Willmann, R.; Pomeroy, R.; Kurien, J. Rights-based fisheries governance: From fishing rights to human rights. Fish Fish. 2012, 13, 14–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, A. A deliberate inclusive policy (DIP) approach for coastal resources governance: A Fijian perspective. Coast. Manag. 2011, 39, 175–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W. Managing Sea Cucumber Fisheries with an Ecosystem Approach; FAO Fisheries and Aquaculture Technical Paper; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2010; No. 516; pp. 1–157. [Google Scholar]

- González-Wangüemert, M.; Valente, S.; Henriques, F.; Domínguez-Godino, J.; Serrão, E. Setting preliminary biometric baselines for new target sea cucumbers species of the NE Atlantic and Mediterranean fisheries. Fish. Res. 2016, 179, 57–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aydin, M. Density and biomass of commercial sea cucumber species relative to depth in the northern Aegean Sea. Thalass. Int. J. Mar. Sci. 2019, 35, 541–550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Domínguez-Godino, J.A.; González-Wangüemert, M. Habitat associations and seasonal abundance patterns of the sea cucumber Holothuria arguinensis at Ria Formosa coastal lagoon (South Portugal). Aquat. Ecol. 2020, 54, 337–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mezali, K.; Lebouazda, Z.; Slimane-Tamacha, F.; Soualili, D.L. Biometry, size structure and reproductive cycle of the sanded sea cucumbers Holothuria poli (Echinodermata, Holothuriidae) from the west Algerian coast. Invertebr. Reprod. Dev. 2022, 66, 67–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vafidis, D.; Antoniadou, C.; Apostologamvrou, C.; Voulgaris, K.; Varkoulis, A.; Giokala, E.; Lolas, A.; Roditi, K. Size structure of exploited holothurian natural stocks in the Hellenic Seas. Sustainability 2023, 15, 13483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzanatos, E.; Georgiadis, M.; Peristeraki, P. Small-Scale Fisheries in Greece: Status, Problems, and Management. In Small-Scale Fisheries in Europe: Status, Resilience and Governance; Springer: Dodrecht, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 125–150. [Google Scholar]

- Voultsiadou, E.; Dailianis, T.; Antoniadou, D.; Vafidis, D.; Dounas, C.; Chintiroglou, C. Aegean bath sponges: Historical data and current status. Rev. Fish. Sci. 2011, 19, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maynou, F.; Recasens, L.; Antoni, L. Fishing tactics dynamics of a Mediterranean small-scale coastal fishery. Aquat. Living Resour. 2011, 24, 149–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, S.L.; Karasik, R.; Stavrinaky, A.; Uchidad, H.; Burden, M. Fishery Socioeconomic Outcomes Tool: A rapid assessment tool for evaluating socioeconomic performance of fisheries management. Mar. Pol. 2019, 105, 20–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, N.J.; Schuhbauer, A.; Skerritt, D.; Ebrahim, N. Socio-economic monitoring and evaluation in fisheries. Fish. Res. 2021, 239, 105934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hair, C.; Foale, S.; Kinch, J.; Frijlink, S.; Lindsay, D.; Southgate, P.C. Socioeconomic impacts of a sea cucumber fishery in Papua New Guinea: Is there an opportunity for mariculture? Ocean Coast. Manag. 2019, 179, 104826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eggertsen, M.; Eriksson, H.; Slater, M.J.; Raymond, C.; dela Torre-Castro, M. Economic value of small-scale sea cucumber fisheries under two contrasting management regimes. Ecol. Soc. 2020, 25, 20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M.A.; Chowdhury, S.H.; Hasan, M.J.; Rahman, M.H.; Yeasmin, S.M.; Farjana, N.; Molla, M.H.R.; Parvez, M.S. Status, prospects and market potentials of the sea cucumber fisheries with special reference on their proper utilization and trade. Annu. Res. Rev. Biol. 2020, 35, 84–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crona, B.I.; Nyström, M.; Folke, C.; Jiddawi, N.S. Middlemen, a critical social-ecological link in coastal communities of Kenya and Zanzibar. Mar. Pol. 2010, 34, 761–771. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purcell, S.W.; Ngaluafe, P.; Foale, S.; Cocks, N.A.; Cullis, B.R.; Lalavanua, W. Multiple factors affect socioeconomics and wellbeing of artisanal sea cucumber fishers. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0165633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishanthan, G.; Kumara, A.; Prasada, P.; Dissanayake, C. Sea cucumber fishing pattern and the socio-economic characteristics of fisher communities in Sri Lanka. Aquat. Living Resour. 2019, 32, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ballikaya, G.; Aydın, M.; Erkan, S. Changes in length-weight relationships of three different commercial sea cucumber during processing and corrected of fisheries data. J. Anatol. Environ. Anim. Sci. 2021, 6, 43–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aprianto, R.; Amir, N.; Kasmiati; Matusalach; Fahrul; Syahrul; Tresnati, J.; Tuwo, A.; Nakajima, M. Economically important sea cucumber processing techniques in South Sulawesi. Indonesia. IOP Conf. Ser. Earth Environ. Sci. 2019, 370, 012082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, M.L.; Brown, E.O. Market potential and challenges for expanding the production of sea cucumber in South-East Asia. In Asia-Pacific Tropical Sea Cucumber Aquaculture; Hair, C.A., Pickering, T.D., Mills, D.J., Eds.; Australian Centre for International Agricultural Research: Canberra, Australia, 2012; pp. 177–188. [Google Scholar]

| Hellenic Fleet | N 139 | LOA 7.57 ± 2.35 | GT 2.84 ± 2.59 | HP 33.71 ± 33.06 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southern Aegean | 26 | 9.18 ± 1.13 | 4.82 ± 3.23 | 40.56 ± 38.59 |

| Ionian Islands | 4 | 7.97 ± 2.11 | 3.39 ± 1.92 | 38.62 ± 25.60 |

| Western Greece | 6 | 5.52 ± 1.43 | 0.95 ± 0.84 | 16.67 ± 8.14 |

| Epirus | 9 | 7.49 ± 1.71 | 2.19 ± 1.20 | 10.31 ± 1.70 |

| Attica | 2 | 8.15 ± 0.78 | 3.37 ± 1.03 | 37.00 ± 0.00 |

| Central Greece | 29 | 6.35 ± 1.54 | 1.69 ± 1.26 | 26.69 ± 23.43 |

| Thessaly | 6 | 7.45 ± 2.19 | 2.99 ± 1.98 | 35.08 ± 23.21 |

| North Aegean | 30 | 7.35 ± 2.04 | 2.79 ± 3.44 | 30.33 ± 30.00 |

| Central Macedonia | 27 | 7.98 ± 3.54 | 2.68 ± 1.55 | 48.70 ± 44.42 |

| Socioeconomic Data | CMac | Th | NAeg | SAeg | Ep |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean age | 50 | 46 | 51 | 50 | 52 |

| Marital status (%) | |||||

| Married | 90 | 100 | 100 | 81.3 | 75 |

| Single person | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6.3 | 25 |

| Divorced | 0 | 0 | 0 | 12.5 | |

| Number of children (mean) | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Education (%) | |||||

| Primary school | 40 | 0 | 33.3 | 40.6 | 25 |

| Junior high school | 0 | 100 | 0 | 21.9 | 25 |

| High school | 30 | 0 | 33.3 | 21.9 | 0 |

| Technical school | 20 | 0 | 33.3 | 9.4 | 0 |

| Higher education graduates | 10 | 0 | 0 | 6.2 | 0 |

| Mean income (EUR) from holothurians | 2000 | 2750 | 1233 | 1375 | 1500 |

| Holothurians as main occupation (%) | 10 | 100 | 33.3 | 96.9 | 0 |

| Holothurians as secondary occupation | 90 | 0 | 66.7 | 3.1 | 100 |

| Years of work in the sea cucumber fishery (mean) | 10 | 8 | 3 | 5 | 3 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Roditi, K.; Antoniadou, C.; Apostologamvrou, C.; Vafidis, D. Métiers and Socioeconomics of the Hellenic Small-Scale Sea Cucumber Fishery (Eastern Mediterranean Sea). Fishes 2025, 10, 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060258

Roditi K, Antoniadou C, Apostologamvrou C, Vafidis D. Métiers and Socioeconomics of the Hellenic Small-Scale Sea Cucumber Fishery (Eastern Mediterranean Sea). Fishes. 2025; 10(6):258. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060258

Chicago/Turabian StyleRoditi, Kyriakoula, Chryssanthi Antoniadou, Chrysoula Apostologamvrou, and Dimitris Vafidis. 2025. "Métiers and Socioeconomics of the Hellenic Small-Scale Sea Cucumber Fishery (Eastern Mediterranean Sea)" Fishes 10, no. 6: 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060258

APA StyleRoditi, K., Antoniadou, C., Apostologamvrou, C., & Vafidis, D. (2025). Métiers and Socioeconomics of the Hellenic Small-Scale Sea Cucumber Fishery (Eastern Mediterranean Sea). Fishes, 10(6), 258. https://doi.org/10.3390/fishes10060258