1. Introduction

Block ciphers are one of the essential cryptographic primitives. Our understanding of building secure block ciphers has greatly improved in the last 20 years. We already have well-understood methods in analyzing block ciphers with a possibly wide range of cryptanalytic tools and techniques including linear and differential attacks and their variants. Linear cryptanalysis is one of the powerful cryptanalytic techniques since its introduction by Matsui [

1]. It is one of the major statistical attacks on block ciphers. Since its invention in the early 1990s, many variations and extensions have been considered. A statistical model to estimate the data complexity of linear attacks was introduced in [

2]. In this paper, we focus on linear cryptanalysis of round-reduced block ciphers: Fantomas, Robin, and iSCREAM. LS-design [

3] ciphers Fantomas and Robin belong to the family of bitslice ciphers proposed by Grosso et al. at FSE 2014. The designers specified two variants of LS-design, namely the involutive cipher Robin and the non-involutive cipher Fantomas. On the other hand, iSCREAM is also an LS-design cipher and uses a tweakable block cipher introduced in Tweakable Authenticated Encryption (TAE) proposed by Liskov et al. [

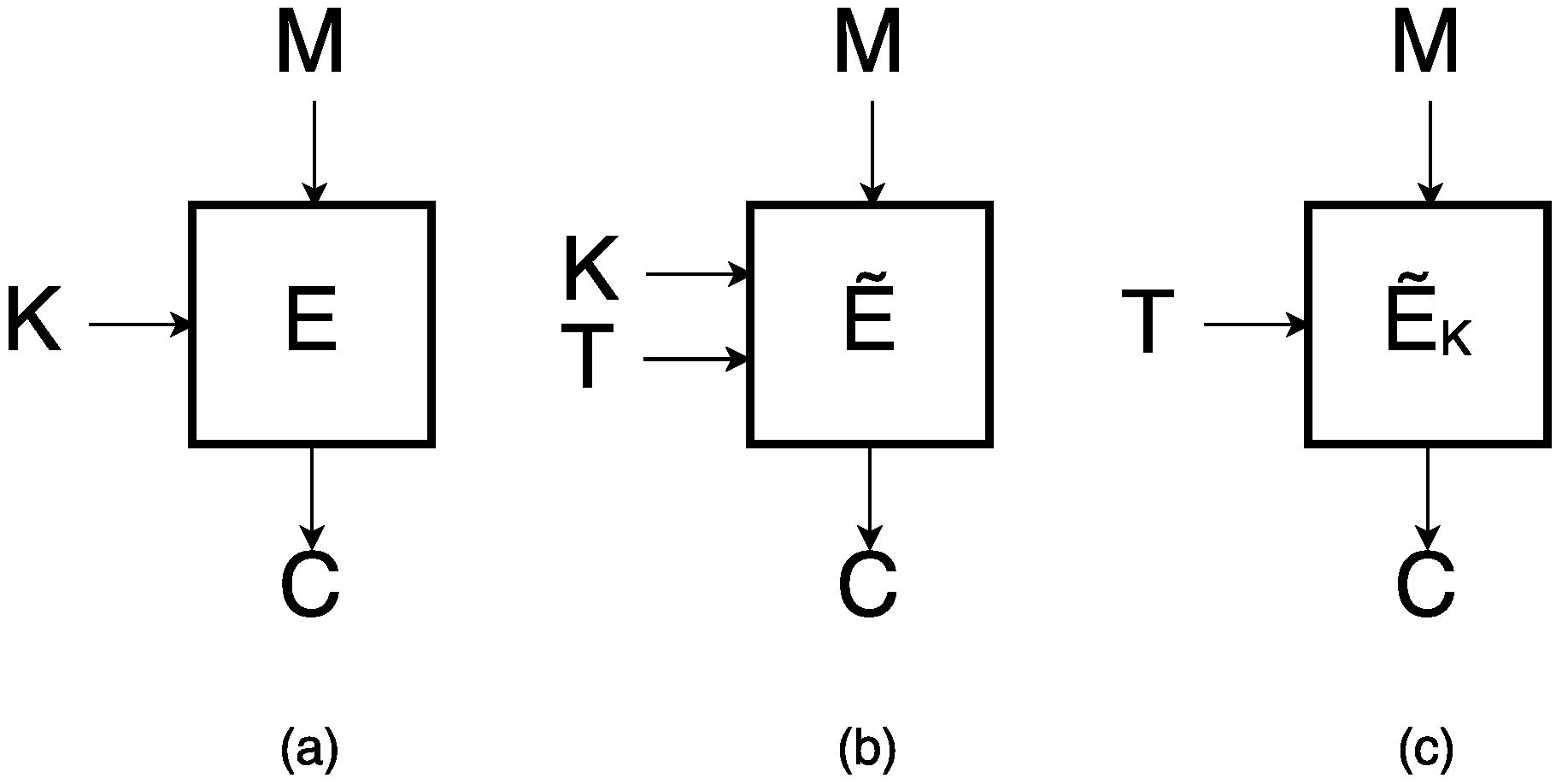

4] and closely related to Robin. Compared to the conventional block cipher, a tweakable block cipher (See

Figure 1) takes an additional input called

tweak.

The great importance of such algorithms has been manifested by the announcement of a public call to the CAESAR competition [

5]. This contest received worldwide attention when it started in 2014. In the first round, 57 algorithms submitted to competition were chosen, with iSCREAM being one of them. We have analyzed all these ciphers with linear cryptanalysis techniques. In this paper, we construct 5-round linear approximations for Fantomas, and 7-round linear approximations for Robin. Using these approximations, we build the 5- and 7-round key-recovery attack for Fantomas and Robin, respectively. We also build 7-round linear characteristics for iSCREAM and based on those linear characteristics we extend the path in the related-key scenario for a greater number of rounds.

2. Related Work

The designers provided some security evaluations (

Table 1) of Fantomas and Robin. The table shows the maximum number of rounds (upper bound) where the attack could be possible (but not necessary).

Shen et al. presented a paper [

6], where they did previously impossible differential cryptanalysis of Fantomas and Robin and constructed 4-round impossible differential and attack 6 rounds of ciphers. As mentioned by authors it was the first impossible differential attack on Fantomas and Robin. Dwivedi et al. presented papers [

7,

8] where they did linear, differential-linear, impossible differential and related-key cryptanalysis of round-reduced Scream, which is closely related to LS-design Fantomas. They presented a key-recovery attack of 5-round with linear and differential-linear, 4-round with impossible differential and 10 rounds with the related-key scenario.

Leander et al. presented a paper [

9], where they introduced a generic algorithm to detect invariant subspaces and with this technique, they cryptanalyzed Robin and iSCREAM. Their attack is on a full cipher yet in a weak or related-key model. A year later, at ASIACRYPT 2016, an attack called the non-linear invariant attack was introduced [

10]. In that paper, the authors showed how to distinguish the full version of tweakable block cipher iSCREAM, Scream and Midori64 in a weak key setting. For the authenticated encryption schemes SCREAM and iSCREAM, the plaintext can be practically recovered only from the ciphertext in the nonce-respecting setting.

In the context of block cipher and image encryption cipher cryptanalysis, different cryptanalytic techniques applied to such ciphers, we have seen some strong papers recently [

11,

12,

13,

14,

15,

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. These authors applied various famous cryptanalytic techniques such as, linear, differential, related-key, impossible differential and produced results for the attack.

3. Descriptions of LS-Designs, Fantomas, Robin and iSCREAM

Fantomas and Robin are two specific LS-designs. The state is represented in the form of matrix. Each element in the matrix represents a bit. The state x is updated by iterating rounds as shown in Algorithm 1. Fantomas is a non-involutive instance and Robin is an involutive instance. Both have SPN structure 128-bit block ciphers with 128-bit key size. The number of rounds in Fantomas and Robin is 12 and 16, respectively. The round function consists of the following layers:

S-box layer: Applying the non-linear 8-bit S-boxes in parallel to each byte of state.

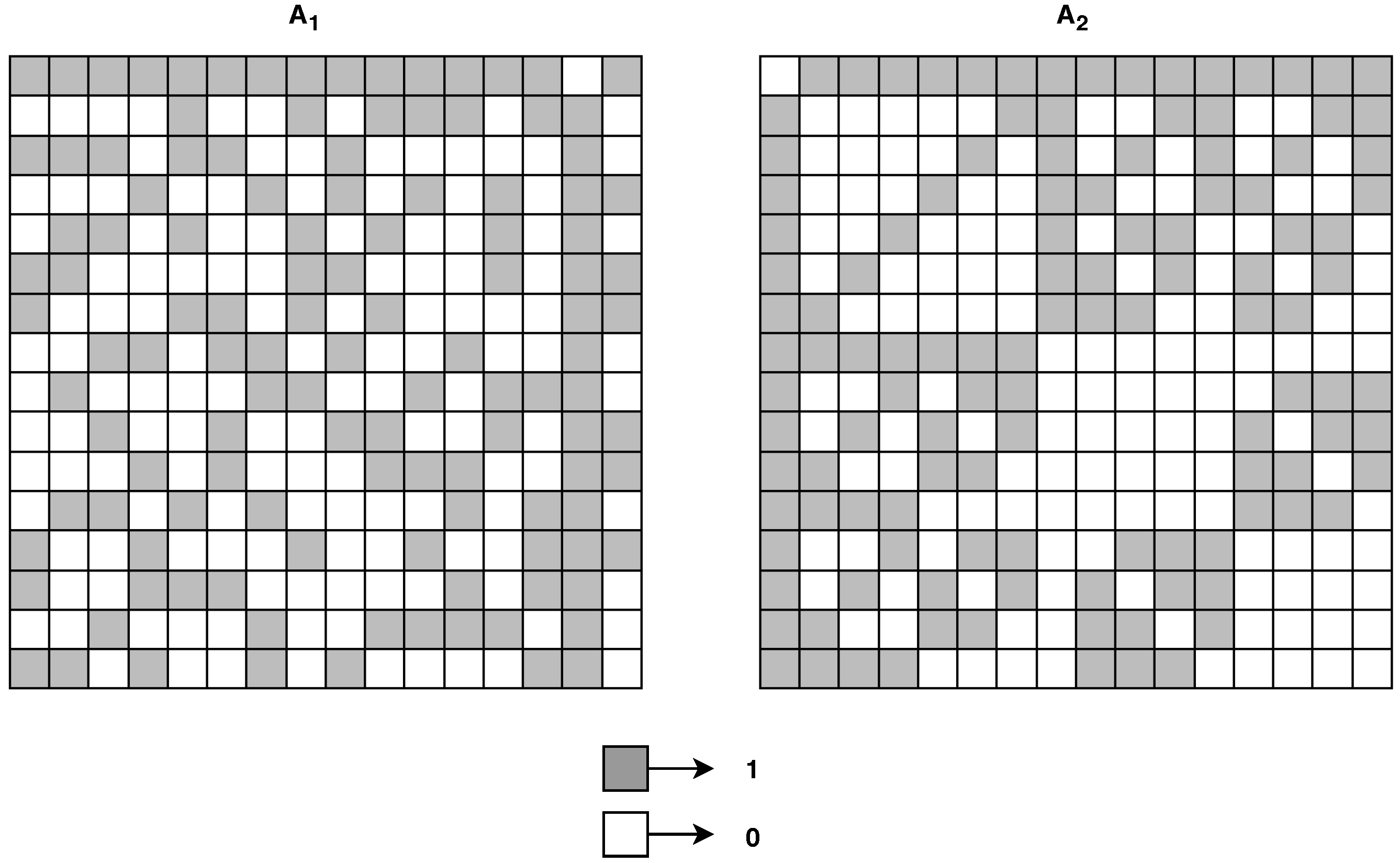

L-box layer: Applying 16-bit L-box with branch number 8. The Fantomas and Robin use two different L-box (

Figure 2).

KC layer: The 128-bit key K and r-th round constant Con(r), XORed with the state.

| Algorithm 1 LS-design with -bit L-boxes and -bit S-boxes . |

| 1: ; | ▹x is a bits matrix |

| 2: for do | |

| 3: for do | ▹ S-box Layer |

| 4: | |

| 5: end for | |

| 6: for do | ▹ L-box Layer |

| 7: | |

| 8: end for | |

| 9: ; | ▹ key addition and round constant |

| 10: end for | |

| 11: return x | |

The designers of Fantomas and Robin directly evaluate the cipher security against the linear attack using a branch number of the linear diffusion layer (L-box) used in both ciphers. The branch number of L-box is defined with Equation (

1). The highest branch number

possible for a 16-bit L-box is 8. In the equation,

x represents the input of L-box and

denotes the output value.

Any two-round trail activates at least

S-boxes. This gives the following 2-round (2r) trail and the maximum bias (see Equation (

2)) of linear trails. Using this property, the best two-round linear trail is possible with bias

(or

for 8 rounds). However, note that designers do analysis based on 2-round best trails and it is not necessary that we can construct even 8-round trail using the best result of any 2-round trail (more details are referred to in [

3]). In our analysis, we present linear trails for a given number of rounds. In the equation,

r represents a round number, and

is the probability of the linear trial.

Descriptions of iSCREAM

iSCREAM is essentially a tweaked version of Robin. The tweakable block cipher iSCREAM is based on the LS-design variant [

3] known as TLS-design. Compared to the conventional block cipher, a tweakable block cipher (See

Figure 1) takes an additional input called

tweak.

The state is represented as an

matrix, where each element of the matrix represents a bit. Therefore, a size of the block is

and iSCREAM has a block size of

bits. The state

x is updated by iterating

steps, where each step has

rounds as shown in Algorithm 2. Several steps can vary, and it serves as the security margin parameter. In the pseudo-code given below a plaintext is denoted by

P, whereas

TK (tweakey) is a simple linear combination of a tweak

T and the master key

K. In iSCREAM, both the key and the tweak are 128 bits long. iSCREAM uses the same L-box (

Figure 2) used by Robin.

| Algorithm 2 TLS-design with -bit L-boxes and -bit S-boxes . |

| 1: | ▹x is a bits matrix |

| 2: for do | |

| 3: for do | |

| | |

| 4: for do | ▹ S-box Layer |

| 5: | |

| 6: end for | |

| ; | ▹ Constant addition |

| 7: for do | ▹ L-box Layer |

| 8: | |

| 9: end for | |

| 10: end for | |

| | ▹ Tweakey addition |

| 11: end for | |

| 12: return x | |

Two different tweak keys are used every two steps by:

where

is a rotation of one bit applied independently to all the (16-bit) rows of the state,

is the number of rounds, and

i is the size of S-box.

4. Linear Approximation of Fantomas

The idea behind linear cryptanalysis is to build a linear characteristic that describes the relation between plaintext and ciphertext bits. Such a relationship should hold with probability 0.5 (bias ) for a secure cipher. Therefore, we try to find a linear characteristic between plaintext and ciphertext where (). This non-random behavior of cipher could be converted to some key-recovery attack.

For a better understanding of linear cryptanalysis, we refer the article

A Tutorial on Linear and Differential Cryptanalysis [

21]. To construct a linear approximation for Fantomas we proceed as follows. First, we construct the linear approximation table of Fantomas S-box, and from the Table, we choose the best linear approximation

(5th input bit of S-box equal to 5th output bit). It has the bias value equal to

. For 5 rounds, the best linear approximation we found has the bias

with 24 active S-boxes. The linear approximation is shown in

Table 2. We use non-involutive L-Box in case of Fantomas.

The number of plaintexts required for the key-recovery attack is typically proportional to

. We also investigate more rounds, but for more than 5 rounds our bias exceeds the limit. For 6 rounds approximation obtained by this method, we exceed the exhaustive search bound of

as we know the size of the state is 128-bit. There are 16 columns in the Fantomas state and therefore 16 S-boxes in S-box layer. We examined

initial states for our linear approximations and found the best trial. We use the same S-box linear approximation

for subsequent rounds. A total bias

is calculated using the formula introduced by Matsui in [

1]. In the below equation,

n is the size of L-box.

5-Round Key-Recovery Attack

We can recover the secret key by using the linear approximation we constructed for the cipher. Firstly, we encrypt the first S-box partially by guessing some key bits. Specifically, we XORed the plaintext bits with the guessed subkey and the result is run forward through the S-box. We need to guess these bits, which are needed to calculate the values of bits involved in the linear approximation.

Table 3 shows the details. For each subkey guess, we create a counter, and it is incremented once the linear approximation holds. A counter with a value which differs the most from a half of several plaintext/ciphertext pairs corresponds to the correct subkey guess.

The given 4.5-round approximation in

Table 3 has a total bias

, and the number of plaintext/ciphertext pairs needed to detect the bias is

. There are 4 active input bits placed in 4 columns of the state. Each column size is 8-bit, and therefore we need to guess

key bits. The number of total possible combinations will be

. We check

possible pairs of plaintext/ciphertext for each combination, and therefore the total complexity of our key-recovery attack is

. To recover more bits, we can repeat the procedure with different approximations, where input active bits are placed in a different position. With this complexity, we do not exceed the exhaustive search bound of

.

5. Linear Approximation of Robin

To construct a linear approximation for Robin we follow similar steps as we did for Fantomas. First, we construct the linear approximation table of Robin S-box, and from the table we choose the best linear approximation

(4th and 5th input bit of S-box equal to 4th and 5th output bit). It has the best bias value equal to

. There are 16 columns in the Robin state and therefore 16 S-boxes in S-box layer. We examine

initial states for our linear approximations. We use the same S-box linear approximation

for subsequent rounds. For 7 rounds the best linear approximation we found has the bias

with the total of 25 active S-boxes. The linear approximation is shown in

Table 4. For the 8-round approximation obtained by this method, we exceed the exhaustive search bound

. Please note that the L-Box table we use in Robin is involutive and not same as Fantomas.

7-Round Key-Recovery Attack

We can recover the secret key by using the linear approximation we constructed for the cipher. First, we encrypt the first S-box partially by guessing some key bits, specifically we XORed the plaintext bits with guessed subkey and result is run forward through the S-box. We need to guess these bits, which are needed to calculate values of bits involved in the linear approximation.

Table 5 shows the details. For each subkey guess we create a counter and it is incremented once the linear approximation holds. A counter with a value which differs the most from a half of several plaintext/ciphertext pairs corresponds to the correct subkey guess.

The given 6.5-round approximation in

Table 5 has a total bias

, and the number of plaintext/ciphertext pairs needed to detect the bias is

. There is 1 active input bit placed in 1 column of the state. Each column size is 8-bit, and therefore we need to guess

key bits. The number of total possible combinations will be

. We check

possible pairs of plaintext/ciphertext for each combination, and therefore the total complexity of our key-recovery attack is

. To recover more bits, we can repeat the procedure with different approximations, where input active bits are placed in different position.

6. Related-Key Linear Cryptanalysis of iSCREAM

We constructed the linear approximation table of iSCREAM S-box, and from the table we chose the best linear approximation

(4th and 5th input bit of S-box equal to 4th and 5th output bit). It has the best bias value equal to

. There are 16 columns in the iSCREAM state and therefore 16 S-boxes in S-box layer. We examined

initial states for our linear approximations. We use the same S-box linear approximation

for subsequent rounds. For 7 rounds the best linear approximation we found has the bias

with total of 25 active S-boxes. The linear approximation is shown in the

Table 6. For 8 round approximation obtained by this method, we exceed the exhaustive search bound

. Please note that the L-Box table we use in iSCREAM is involutive and same as Robin.

7. Conclusions

In this paper, we have analyzed LS-design ciphers Fantomas, Robin, and iSCREAM using linear cryptanalysis. Our findings help to quantify the security margin of these ciphers against linear attacks. We conclude the analyzed ciphers have enough security margin against this attack for a full number of rounds. We have not used any standard automatic heuristic tools to calculate linear characteristics for each cipher. Our analysis provides state-of-the-art results but within a simpler framework. We believe it is essential to analyze such new, promising algorithms with a possibly wide range of cryptanalytic tools and techniques. Our work here helps to realize this goal.

Author Contributions

All authors contributed equally to this work. All authors wrote, reviewed, and commented on the manuscript. All authors have read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Funding

The work of Ashutosh Dhar Dwivedi and Rajani Singh is funded by Polish National Science Centre, project DEC-2014/15/B/ST6/05130.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Matsui, M. Linear Cryptanalysis Method for DES Cipher. Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT ’93; Helleseth, T., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1994; pp. 386–397. [Google Scholar]

- Blondeau, C.; Nyberg, K. Joint data and key distribution of simple, multiple, and multidimensional linear cryptanalysis test statistic and its impact to data complexity. Des. Codes Cryptogr. 2017, 82, 319–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosso, V.; Leurent, G.; Standaert, F.; Varici, K. LS-Designs: Bitslice Encryption for Efficient Masked Software Implementations FSE; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2014; Volume 8540, pp. 18–37. [Google Scholar]

- Liskov, M.; Rivest, R.L.; Wagner, D. Tweakable Block Ciphers. J. Cryptol. 2011, 24, 588–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CAESAR: Competition for Authenticated Encryption: Security, Applicability, and Robustness. Available online: http://competitions.cr.yp.to/caesar.html (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Shen, X.; Liu, G.; Li, C.; Qu, L. Impossible Differential Cryptanalysis of Fantomas and Robin. IEICE Trans. Fundam. Electron. Commun. Comput. Sci. 2018, E101.A, 863–866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Morawiecki, P.; Singh, R.; Dhar, S. Differential-linear and related key cryptanalysis of round-reduced scream. Inf. Process. Lett. 2018, 136, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Morawiecki, P.; Wójtowicz, S. Differential-linear and Impossible Differential Cryptanalysis of Round-reduced Scream. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications—Volume 6: SECRYPT (ICETE 2017), Madrid, Spain, 24–26 July 2017; SciTePress: Setubal, Portugal, 2017; pp. 501–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leander, G.; Minaud, B.; Rønjom, S. A Generic Approach to Invariant Subspace Attacks: Cryptanalysis of Robin, iSCREAM and Zorro. In Advances in Cryptology—EUROCRYPT 2015; Oswald, E., Fischlin, M., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2015; pp. 254–283. [Google Scholar]

- Todo, Y.; Leander, G.; Sasaki, Y. Nonlinear Invariant Attack: Practical Attack on Full SCREAM, iSCREAM, and Midori64. J. Cryptol. 2018, 1–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lin, D.; Feng, B.; Lü, J.; Hao, F. Cryptanalysis of a Chaotic Image Encryption Algorithm Based on Information Entropy. IEEE Access 2018, 6, 75834–75842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Lin, D.; Lü, J.; Hao, F. Cryptanalyzing an image encryption algorithm based on autoblocking and electrocardiography. IEEE MultiMedia 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar Dwivedi, A.; Morawiecki, P.; Wójtowicz, S. Differential and Rotational Cryptanalysis of Round-reduced MORUS. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications—Volume 6: SECRYPT, ICETE, Madrid, Spain, 24–26 July 2017; INSTICC, SciTePress: Setubal, Portugal, 2017; pp. 275–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Klouček, M.; Morawiecki, P.; Nikolić, I.; Pieprzyk, J.; Wójtowicz, S. SAT-based Cryptanalysis of Authenticated Ciphers from the CAESAR Competition. In Proceedings of the 14th International Joint Conference on e-Business and Telecommunications—Volume 6: SECRYPT, ICETE, Madrid, Spain, 24–26 July 2017; INSTICC, SciTePress: Setubal, Portugal, 2017; pp. 237–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G. Differential Cryptanalysis of Round-Reduced LEA. IEEE Access 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Morawiecki, P. Differential cryptanalysis in ARX ciphers, Application to SPECK. IACR Cryptol. ePrint Arch. 2018, 2018, 899. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Morawiecki, P.; Wójtowicz, S. Finding Differential Paths in ARX Ciphers through Nested Monte-Carlo Search. Int. J. Electron. Telecommun. 2018, 64, 147–150. [Google Scholar]

- Dhall, S.; Pal, S.K.; Sharma, K. A chaos-based probabilistic block cipher for image encryption. J. King Saud Univ. Comput. Inf. Sci. 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhall, S.; Pal, S.K.; Sharma, K. Cryptanalysis of image encryption scheme based on a new 1D chaotic system. Signal Process. 2018, 146, 22–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, A.D.; Srivastava, G. Differential Cryptanalysis in ARX Ciphers with Specific Applications to LEA. Cryptology ePrint Archive, Report 2018/898, 2018. Available online: https://eprint.iacr.org/2018/898 (accessed on 9 January 2019).

- Heys, H.M. A Tutorial on Linear and Differential Cryptanalysis. Cryptologia 2002, 26, 189–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).