1. Introduction

“In short, if there were a modern political cinema, it would be on this basis: the people no longer exist, or not yet…

the people are missing” [

1] (p. 216). Thus, Gilles Deleuze, in

Cinema 2: The Time-Image, renders his verdict on political cinema following World War II, which is supposedly no longer characterized by a unified people on the order of early Soviet cinema (in Pudovkin, “the people already has a virtual existence in process of being actualized”) or prewar Hollywood (“the unanimism of King Vidor, Capra, or Ford”) [

1] (p. 216).

Deleuze’s discussion is marked by two curious turns. First, while his opening paradigms of modern political cinema are Western European (Alain Resnais’s

La guerre est finie [1966] speaks to a “Spain that will not be seen”, and the Straubs’

Not Reconciled [1965] raises the question of the very existence of the German people), his treatment is most evocative, and reaches its crescendo with “third world filmmakers”, most famously the Brazilian Glauber Rocha. Therefore, the absence of a “people” in Latin American cinema emerges as an extreme version of the European situation: Deleuze ironically risks being pinned to the same paternalism—of understanding the colonial and neocolonial situation in Latin America using European categories—that Rocha himself criticized in his 1965 manifesto “An Aesthetics of Hunger”

1 [

2].

The other curious turn involves Deleuze’s view that the formulation “the people are missing” is in fact consistent with the existence of many peoples: he refers to “the consciousness that there were no people, but always several peoples, an infinity of peoples, who remained to be united, or should not be united, in order for the problem to change” [

1] (p. 220). The “problem” to which he refers is an absence of unity, the problem of producing “collective utterances”; modern political cinema then becomes an exemplar of the politics of recognition [

1] (p. 222). We are thus faced with a question of scale. For example, is there some kind of “unity” or “collective utterance” missing from the Super 8 films made by the Ikoots Indigenous women in San Mateo del Mar, Oaxaca, at the first Indigenous Film Workshop in Mexico in 1985 [

3,

4]? If so, what would sustain that idea—of these films as speaking not from

one people, but from one of an “infinity of peoples”—other than the conflation of a unified “people” with the people of a recognized nation-state?

Nevertheless, assuming that there exists a problem of producing “collective utterances” in modern political cinema, the solution that Deleuze attributes to Rocha is striking, and has enjoyed enormous influence in contemporary Latin American experimental film [

5]: to induce an experience of

trance (referring to Rocha’s film

Terra em Transe, 1967). Deleuze says, “The author [Rocha] puts the parties in trances in order to contribute to the invention of his people who, alone, can constitute the whole [

ensemble]. […] As a general rule, third world cinema has this aim: through trance or crisis, to constitute the assemblage which brings real parties together, in order to make them produce collective utterances as the prefiguration of the people who are missing […]”

2 [

1] (p. 223).

The proposed solution of the trance as people-producing or people-sustaining power is provocative, but Deleuze’s official formulations are too close to being of an empty trance or an idealist trance to close the gap on a “missing” people. Is there any way of arriving at the “collective utterance” of a unified people while avoiding the material questions of political problem-solving? The view I will explore in this essay is that the characteristic way for a people to go “missing” under capitalism involves the obfuscation of their labor: no filmic trance can meet the high political expectations that Deleuze sets for that kind of experience—the collective utterance of a people—without some recognition of the peculiar temporality of the workday of the people in question.

The additional view I will explore is that experimental film and video art are typical sites of such obfuscation—especially when they depend on private or closed forms of circulation and exhibition—which is what makes critiques within those media, reemploying the waste and detritus produced in their production, such important paradigms of the materially grounded “collective utterance” or the Rocha-like “trance”.

Here, two works by the Oaxaca-based Mexican experimental filmmaker and video artist Bruno Varela are relevant and will be my focus in this essay: Papeles Secundarios (Supporting Roles, 2004) and Cuerpos Complementarios (Complementary Bodies, 2022), both drawn from material shot by Varela during his time as casting director in Oaxaca of famed Iranian artist Shirin Neshat’s video installation Tooba (2002). Varela’s critique of his former employer’s work amounts to the idea that the latter’s resulting trance is indeed idealist, owing to concrete senses in which the “people are missing” in Tooba. By elliptically exposing the peculiarities of the workday of the Oaxacan extras in Neshat’s video installation and by remaining in free, open circulation online, Varela’s works aim to reveal the obfuscations of human labor involved in what he calls “plantation cinema” or “extraterrestrial cinema” (a cinema of extraction). Taking Varela’s critique seriously also requires approaching the broader debates about Tooba’s “universalism” or “transnationalism”, and indeed the question of when universalism is pinned to colonialism.

Thus,

Papeles Secundarios and

Cuerpos Complementarios go beyond what has been regarded as the “cliché about [the] invisibility” of labor in cinema [

7] (p. 267n9), [

8] (pp. 1–2). These films deepen possibilities of the making-of documentary genre as source of

baroque critiques of the philosophical pretensions of their original filmic subjects, to adopt a formulation by Mexican Marxist philosopher Carlos Oliva Mendoza [

9]. (The unwieldy situation is that, in doing so, they are then easily exposed to critiques of their own philosophical pretensions, as is the case with this very writing on it). Thus, these works also deepen understandings of those dialectical contexts needed for films to make philosophical statements that, in academic discussions, are likewise typically obfuscated, and for reasons perhaps themselves rooted in the obfuscation of labor.

Indeed, the baroque or neo-baroque aspects of the critiques offered by these works allow for a more complex approach to temporality than simply representing the workday of the film set. They show how the trans-temporality or temporal playfulness of trances or transcendental experiences communicated on film may be either earned or unearned, and earned only when rooted in an unvarnished view of a people and their workday.

2. Filming Tooba in Oaxaca

At the end of 2001 and beginning of 2002, the highly accomplished New York-based Iranian artist Shirin Neshat came to the southern Mexican state of Oaxaca to film the two-channel video installation

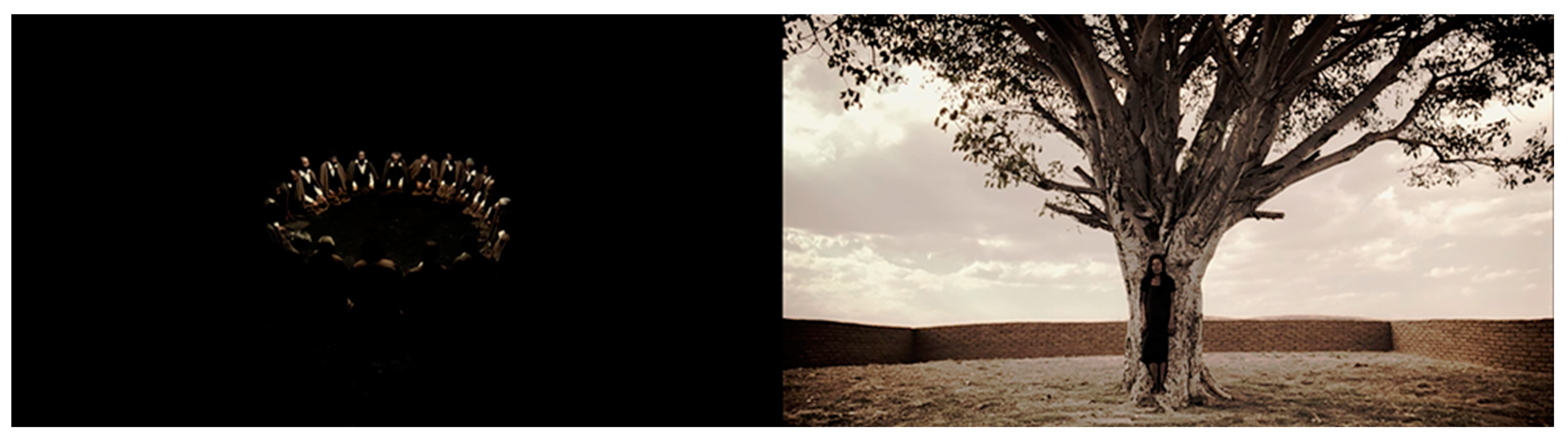

Tooba with a crew that included other Iranian exiles, such as Academy Award-nominated Iranian cinematographer Darius Khondji. The now widely-discussed work consists of shots of a hilly landscape, where black-clad middle-aged men and women run up a hill and converge on a tree buttressed by a woman, intercut with shots of a chanting all-male “inside council” [

10] (p. 78)

3 (

Figure 1). As the crowd converges on the tree, separated by an enclosed adobe wall, the woman slowly fades away: perhaps becoming the tree itself, drawing on Neshat’s avowed inspiration in Shahrnush Parsipur’s 1989 novel

Women without Men, in which the woman Mahdokht undergoes a similar transformation [

12]

4.

Neshat’s powerful and serious film is typically understood as communicating a search for peaceful or trascendental “sanctuary” from the “aggression” of the crowd [

14] (p. 104)

5, [

10] (p. 78). Thus, Neshat says, “In the Quran, Tooba is a tree in paradise; in Iranian common culture it is a feminine tree. […] The tree of Tooba in the middle of the garden represents a place that is sacred, a refuge, a sanctuary, security” [

14] (p. 104). Despite the film’s basis in narratives of women becoming trees (Neshat’s husband, artist Shoja Azari, says “the women

is the tree” [

16]), most commentators emphasize her seeming disappearance. Scott MacDonald says that “by the time the groups of women and men arrive, the spirit has disappeared” [

17] (p. 625). Erin C. Devine says, “When she disappears upon their advance, her passiveness is powerful and underestimated, defying the forces that seek to control it” [

10] (p. 78). Additionally, Neshat herself has said, “She represented a spirit that had a body, and yet no longer had a body” [

16].

This ready association between the film’s communication of transcendental experience and

disappearance underscores the provocation involved in, and the work needed to understand, Deleuze’s proposal of the trance as a people-sustaining power. Such focus on the film’s ethereality seems likewise stressed by the dominant theme among commentators of its transnationality: it seems to be a film from anywhere or from nowhere [

15] (pp. 167–96), [

10] (pp. 78–80). The work’s supposedly mixed response following its premiere at documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany, has been attributed to its departure from Neshat’s previous engagements with self-evidently Iranian and Islamic themes and iconography, such as the

chador or veil [

10] (p. 78) (and yet strikingly, it was also Neshat’s first film exhibited in Iran)

6.

Originally imagined for Neshat’s native Qazvin, Iran (thinking of her father’s farm, which according to the artist became a source of dispute with the Iranian state), any possibility of filming there was further scuttled by 9/11 and the War on Terror, the very events that Neshat would later name as inspiring her focus “on the idea of a garden—a heaven”

7 [

14] (pp. 103–104), [

17] (p. 645). Hence the production’s move to Mexico, embracing the country’s previous unfamiliarity to Neshat and what she called its character as “the most neutral country, meaning neither Islamic nor Western” [

17] (p. 645). According to Shiva Balaghi, “she chose Mexico, as an alternative third space whose landscape recalled Iran’s” [

14] (p. 104).

In arriving in Oaxaca for location scouting, the crew settled on a fig tree (“which

is a sacred tree”, as Neshat says [

17] (p. 645)) in the settlement El Manzano, Agencia de Tiracoz, in the historically significant municipality of Cuilápam de Guerrero, in the central valley region of Oaxaca, with filming of the “inside council” taking place in the local San Miguel Arcángel chapel. As the artist recounts, “[The tree] was on top of a mountain where there was no road, so we had to make the road to get to it. We built the wall around the tree, hired local assistance, and began to cast” [

17] (p. 645), where they specifically sought between three hundred and four hundred local extras of at least forty years old. These artificial interventions in a foreign landscape are ironically motivated by the idea of sanctuary. For example, Balaghi discusses the four-sided wall that Neshat’s production installed, drawing on Foucault’s treatment of the Persian garden as “a sacred space that was supposed to bring together inside its rectangle four parts representing the four parts of the world” [

14] (p. 104), [

18] (p. 234).

It is unusual for most short video installations to have any films made about their production. A truly remarkable fact about the thirteen-minute Tooba is that no fewer than four films have been made about it: two by Iranian exiles on its crew, and the two works by its casting director, Bruno Varela, that I will discuss shortly. The Making of Tooba (2012), by the film’s production designer Shahram Karimi, is a conventional eleven-minute account of the film’s production, consisting of “talking head” interviews with Neshat, Khondji, and Azari, where the mariachi opening of the song “Despacito” by Paquita la Del Barrio stands metonymically for “Mexico”, and where none of the Oaxacan non-professional actors are interviewed or profiled.

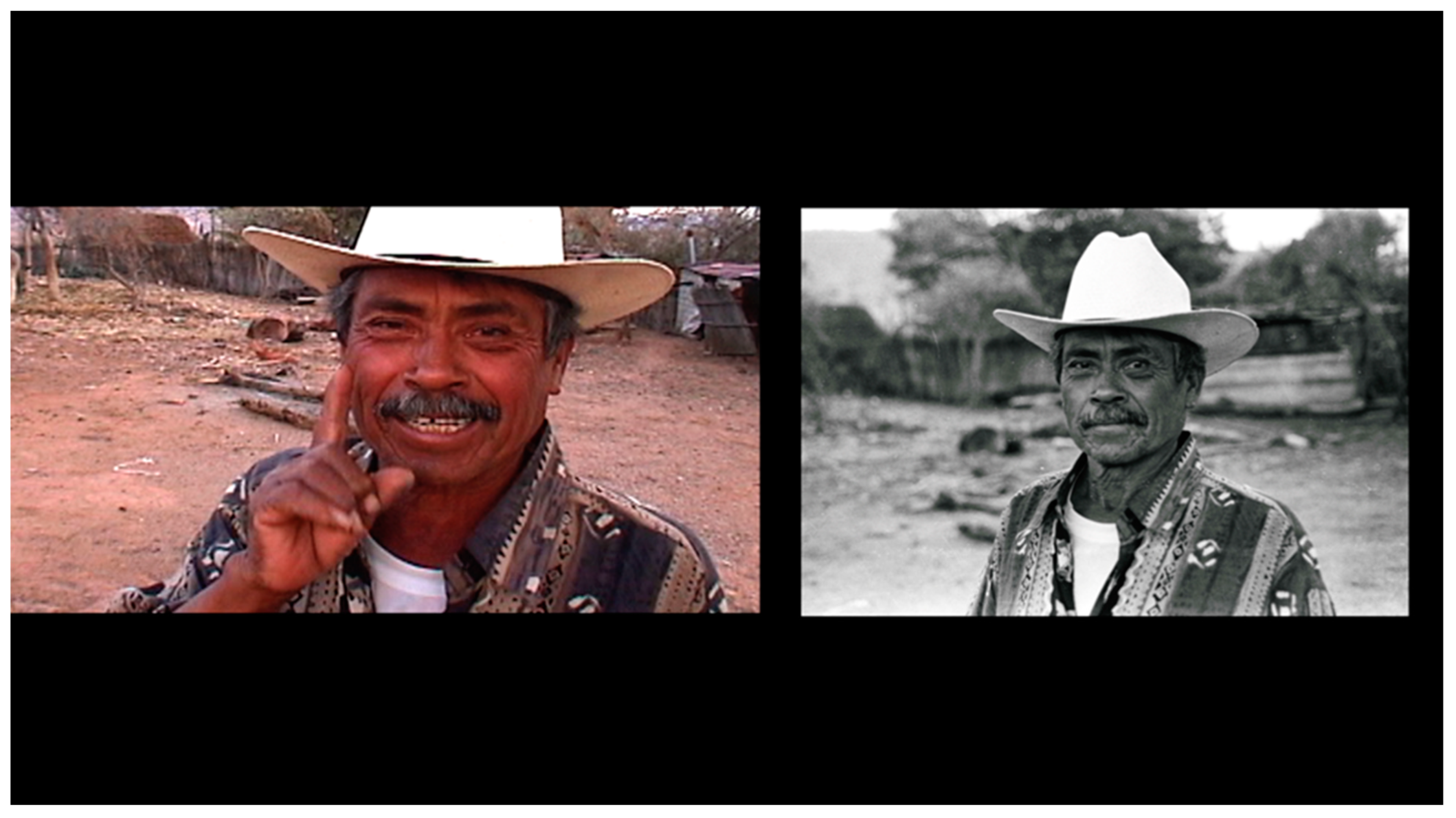

In fact, the footage and musical tropes of Karimi’s documentary are drawn from a prior work, the extremely different and much more interesting hourlong fictionalized mockumentary

María de los Ángeles (2003), by Neshat’s husband Azari, titled after the non-professional actress playing the woman in the tree (as she is credited in Neshat’s film)

8 (

Figure 2). Balaghi describes it as a film “following the search for the tree, for the location, for the cast” that also, in its opening sequence, “self-consciously mimics Abbas Kiarostami’s 1999 film

The Wind Will Carry Us” [

14] (p. 97). Its first half also anticipates by two years some of the same making-of mockumentary techniques (such as a foreign crew in search of an elusive film) as Lourdes Portillo’s

Al más allá (2005), also shot in Mexico.

In María de los Ángeles, cuts showing the new adobe wall and the newly carved-into fig tree are shocking in revealing the production’s sudden obtrusion into the foreign landscape. Additionally, it can be genuinely affecting to view the story of the woman María de los Ángeles as she suffers sexual innuendo and harassment from local men, mockery from locals for appearing as Neshat’s protagonist, and then abandonment once the production leaves town, her only respite found in returning to the tree (where she had earlier dreamt the entirety of Neshat’s film—underlying the latter’s relationship to experiences of trance). The film goes beyond melodramatic clichés of the abandoned woman (in effect tying María to Golden Age Mexican melodramas starring María Félix, Dolores del Río, and Marga López) by proffering the question of the future facing the locals once the production of Tooba leaves Tiracoz.

Azari’s accounts of his film’s relationship to

Tooba are trenchant and honest, describing his own involvement in the neocolonialism of foreign productions, with few illusions about the ironies of Iran’s own colonial and neocolonial history and how exile in the U.S. allows for access to Western capital. “We have come to the U.S. and become artists. We have accessibility. When we make art in Morocco and in Mexico there is a colonialist aspect to it. It always affects us. You walk away drained and exhausted, because of the relationship that is created” [

14] (p. 104) (

Figure 3). In another discussion of his “making-of documentary” he says even more bluntly, “my feeling was that basically the practice of filmmakers as they go to a foreign land to make a film is that of the colonialist. They go to these small villages of really poor people and basically exploit the hell out of them” [

19]. In correspondence, Azari has echoed these concerns, while also remarking on the problems of focusing on the exploitation involved in smaller productions like

Tooba at the expense of that “embedded in the studio film industry” [

20].

These statements by Azari can seem like direct responses to Neshat’s comment—among those criticized by Hamid Dabashi as “condescending”—that, remarking on the poverty of the local populations involved in these foreign productions, “I have always felt proud about this aspect of the projects, which on a modest scale are able to make an economic contribution to the local communities” [

17] (p. 645). Dabashi’s criticisms of Neshat appear in some of the finest and most subtle writing on her art, as part of a complex dialectical maneuver in which the scholar argues that “Visually she is completely emancipated from the binary [East-West—Islam versus Modernity] precisely because verbally she is so caught up in it” [

15] (p. 191).

And yet the condescension that Dabashi detects in Neshat’s relationship to local populations is simply a concession in his account of her “formally quite liberating” visuals—not, unlike her supposed “Islam versus Modernity” rhetoric—part of what, according to the author, those visuals emancipate us from. That is, what Azari describes as the colonialism of these productions is not yet resolved in the Hegelian

aufgehoben of Dabashi’s complex defense of Neshat (liberating visuals overcoming the limitations of her verbal rhetoric)

9. Likewise, Oaxaca itself makes no real appearance in Dabashi’s discussion of

Tooba. (Dabashi wittily criticizes Scott MacDonald’s inaccurate descriptions of the locations of Neshat’s Moroccan productions, but adds that “the quintessential factor in [MacDonald] sparing Mexico [from these inaccuracies] is not that it is not in the Middle East, but that it is Christian”, thus himself eliding the intricacies of Catholic and Indigenous “syncretism” in Mexico).

The

telos of the dialectical process in Neshat’s “transnational” cinema that Dabashi describes is universalism: “visual emancipation of Neshat’s universal concerns” [

15] (p. 192). Azari describes it as form of colonialism (while also raising the question of which film productions are not so implicated). A perhaps unanticipated consequence of this process is that the detritus of these foreign productions can itself become the material for their local critique, thus raising somewhat different philosophical issues that are less adaptable to documentary or mockumentary conventions.

3. Papeles Secundarios and Cuerpos Complementarios

In the above-quoted account of her foreign productions, Neshat says, “Usually we hire local people as coordinators—such as the casting director, project manager, a line producer, and others. To recruit local people you need local persons who are well-liked by the community and have some experience in organizing events” [

17] (p. 645). The local casting director for

Tooba was precisely the young artist Bruno Varela, born in Mexico City in 1971 and located in Oaxaca since 1994 (with a period in Bolivia in the late 90s), then enjoying one of his most fruitful and important early periods of artistic output. At this time, Varela shared the filmmaking collective Arcano Catorce with Isabel Rojas (also production coordinator of

Tooba) and additionally collaborated in various projects in Oaxacan community cinema and video, including the workshops Mirada Biónica and Yo veo al pueblo, and the projects Ojo de Agua Comunicación and Colectivo Turix, as well as the film club El Pochote (founded by famed artist Francisco Toledo).

Though Varela is now likely the best-known audiovisual artist to emerge from Oaxaca in the early 2000s, the same period saw a flourishing of experimental work by Rojas (

Ensalda de nopal, 2004), Roberto López Flores (

Huésped, 2006), Hanne Jiménez Turcott (

Como prepararse para el matrimonio, 2004), and Gustavo Mora (

Federico en su cueva, 2005), among others. This is in addition to the period’s extraordinary efforts in Indigenous video, which in fact challenge the categories of “experimental” and “community” cinema. These include

El señor del rayo (Marcos Sandoval, 2000), on the Triqui rain petition in San Andrés Chicahuaxtla;

Flor mujer (Carlos Sánchez Martínez, 2003), on the flower banquet in Juchitán de Zaragoza;

Xua’a (Natividad Cruz Pérez and Maribel Santiago Cruz, 2003), on the milpa in Santa Cruz Yagavila;

Dulce Convivencia (Filoteo Gómez Martínez, 2004), on panela production in the Mixe region of San Miguel Quetzaltepec; and

Mi viaje al Perú (Colectivo Turix, 2003). Varela is strongly dedicated to preserving the memory of this period in his archival, exhibition, and indeed filmmaking work

10.

As a non-Indigenous filmmaker originally from Mexico City, Varela occupied an intermediate class position—indeed, a middle-managerial one—as casting director of Neshat’s

Tooba. But as a consequence of this middle position, according to Varela, he was able to take advantage of a loophole in the prohibition of private photography on the set, with the cover that his own recordings were part of his casting work. These included not only MiniDV recordings of the production, but also about three hundred black-and-white 35 mm still negatives. According to Varela, once Azari took stock of this project, he offered to buy this material from him, so that it could be included in

María de los Ángeles, but by that time, Varela was too far in editing it into

Papeles Secundarios (2004). (In correspondence, Azari has said that he does not recall this interaction, though grants that it likely took place [

20]).

The title of Varela’s ten-minute film (“Supporting Roles” or “Secondary Roles”) alludes to the central role it gives to the non-professional Oaxacan actors placed as semi-anonymous members of a crowd in

Tooba (and made nearly invisible in Karimi’s

The Making of Tooba) [

21]. It opens with a seemingly extraterrestrial or otherworldly setting: the black-clad actors wandering towards the fig tree, accompanied by eerie, shrill electronic music that Varela himself produced using the application Garageband. The virtually science-fiction soundtrack also boasts walkie-talkie dialogue in English and Spanish from Neshat’s production, as well as Varela’s voice, with characteristically poetic reflections on the metaphysics of image production: “I find an old photo in the middle of books. The images wait in the wings, put into operation. An old cassette contains the germ of history”

11. Varela’s frequent device of strips of paper displaying titles—here announcing the film’s theme as “

encuadramientos” (“framings”), and accompanying Varela’s scattered 35 mm still prints of the actors—also rely on the title’s punning use of

papeles (meaning either “papers” or “roles”).

Different actors speak directly, out of costume, to Varela’s MiniDV camera, giving their names, ages, and origins in and around Tiracoz. We then learn the rest of the name (“Chávez López”) of the woman in the tree, credited as “María de los Ángeles” in Neshat’s film (the basis of the title of Azari’s work). An announcement of the casting is heard over loudspeaker, where the announcer is conspicuously framed by a headdress of Oaxaca’s famous Danza de la Pluma: the dance, with supposed origins in Cuilápam de Guerrero, memorializing the Spanish Conquista and Catholic evangelization of Mexico (

Figure 4).

Intercut with faces of other actors, an older man talks about leading Neshat and Azari to the tree and their negotiating the permissions to film with the municipal president, and of this man’s expectations that the filming will be to the benefit of everyone there. His attitude is shared by Ángeles Chávez López, the woman in the tree, who says she enjoys this work, disregarding the negative opinions of others in the town (remarks evocative of the harassment and mockery her character receives from locals in María de los Ángeles). Meanwhile, in a moment of complex irony, it is hard not to perceive Varela as criticizing the stances of Neshat, Azari, and Karimi as they impersonally block her placement in the shot. (Would María de los Ángeles also disregard Varela’s opinion?).

Another man speaks of the town’s past suspicion of outsiders and of the previous difficulties, prior to the construction of a road fifteen years earlier, in reaching the capital, Oaxaca City, while likewise Ángeles speaks of their lighting practices by gas prior to the arrival of electricity a decade earlier. Yet another man talks about how the foreign crew was content because they were treated well by the locals.

The film’s remarkable conclusion is colored by the possible melancholy, indeed ominousness, of play or leisure, as though to ask, “What will happen after the production leaves the town?” and “What is to be done at the end of the workday?” Varela’s film also locates itself as the product of post-workday play (the proverbial

workers leaving the factory as the genesis of filmmaking) [

22]. As the soundtrack of eerie music and walkie-talkie dialogue reemerges, a drunk man stumbles past a gate, and we see the set give way to dancing, maskwearing (plastic and papier-mâché masks of frogs, rabbits, pigs,

chinelo dancers, originally derived from the scene of the locals’ mockery of the actress in

María de los Ángeles), as well as relaxed laughter, where this play is most importantly

for the camera (

Figure 5).

In contrast with the semi-anonymizing framing of Neshat’s approach to the crowd in

Tooba, this self-theatricalization in moments of leisure becomes a moment for the employees to assert their agency, or more precisely to

play at asserting their agency. (It is prepared for earlier in the film by a man who declines to give his name to Varela’s camera, instead adopting the “mask” of saying “I am like the gale that is out for a walk”)

12. Finally, following titles explaining the production (“the construction of a road leading to nowhere”), we hear Neshat ask in English, “Bruno, what kind of an artist are you?”, at once demonstrating Varela’s view of the condescension towards locals criticized by Dabashi and yet also revealing the film’s appreciation of its roots in the reflection invited by that question.

The shorter, five-minute

Cuerpos Complementarios (2022) represents Varela’s return to this material nearly two decades later, following fresh digitizations of his 35 mm photographs [

23] (

Figure 6). Placing these stills of the actors in quick succession constitutes a re-animation of the “complementary bodies” of its title—its subtitle is “a film made from body parts”—as though responding to the several senses of “missing bodies” at play in

Tooba (in Neshat’s remark about “a spirit that had a body, and yet no longer had a body”, as well as her semi-anonymizing framing of the Oaxacan cast) (

Figure 7). With the black-and-white photographs operating themselves as “body parts”, detritus from an earlier production and perduring registers of the cast’s bodily aspects, the re-used “science fiction” soundtrack of

Papeles Secundarios now takes on features of a monster movie (the return to the personal archive as the province of Dr. Frankenstein).

The film is likewise structured by questions of “return” to earlier digital formats. Its multi-screen presentation of the stills and the MiniDV material from the earlier film (dividing into two panels, then three) alludes not only to video presentations outside of galleries of the two-channel

Tooba but also to the dominant form of “making-of” documentaries at the time of

Papeles Secundarios in the early 2000s: the DVD “extra”, and especially what Craig Hight profiles as interactive

multi-text making-of documentaries on DVDs

13 [

24] (

Figure 8,

Figure 9 and

Figure 10). Indeed, Varela’s speeded-up presentation of the older footage appears like a DVD fast-forward function, accentuated by the smeared lines resulting (like detritus) from hand-scanning the 35 mm stills. Even the repetition of an old Nokia ringtone from the earlier film—in

Papeles Secundarios, a figure for the invasion of capitalist modernity—now in

Cuerpos Complementarios serves to send us a couple of decades backwards in time.

The titles in

Cuerpos Complementarios (now liberated from the paper strips) are particularly direct and incisive: beyond their mentions of “surveying and framing”, “measurement and valuation”, and “living sculpture woven from bodies”, they also ask “What happened to the adobe fence after being an image?” and “Who cleaned the church transformed into an improvised studio?” We are told that “two trees were mutilated during filming” and that the employees’ “medical insurance never worked”

14. Fundamentally, according to Varela, “the images were never returned”, constituting a form of “plantation cinema” or “extraterrestrial cinema”

15.

This remark on the images having never been returned to the bodies or people from whom they were taken alludes to the fact that Tooba’s exhibition has principally been via private collections. (Its last screening in Mexico was part of an exhibition of work belonging to the Isabel and Agustín Coppel Collection [CIAC] at Mexico City’s Laboratorio Arte Alameda in 2022; in Oaxaca City it was shown in 2003 in the Contemporary Art Museum of Oaxaca and in 2007 in the film club El Pochote, likewise in those instances as part of the CIAC.) Papeles Secundarios itself saw elite exhibition at the Guggenheim’s 2005 series In the Air: Projections of Mexico and in 2006 at LUX’s Artists Cinema in London, and was even proposed for the 2007 Flaherty Seminar, to be screened with Tooba, although that plan never came to fruition. The film has nevertheless been freely available on Varela’s Vimeo channel since 2011, as has Cuerpos Complementarios since its production in 2022. No one should be under the illusion that free exhibition on Vimeo itself constitutes a “return” of the images to those from whom they were extracted, or even an interrogation of what such a thing might be.

Remarkably, though, Varela’s suggestion that closed distribution of a people’s images via private collection is a form of exploitation has its own connection to one of the works that inspired

Tooba, Shahrnush Parsipur’s novel

Women without Men. There, the knitter Mahdokht does not exactly fade away or lose her body; rather, in reacting against the industrialization of sweater production, she actively plants herself as a tree, which is then (she imagines) ironically harvested and sold in California [

12]. Better put, then, the standing tendency for bodies and peoples to “disappear” under capitalism is owing to the exploitation and extractivism of those same bodies. Thus, the responsibility of filmmakers (and academic writers) communicating

sanctuary or

leisure is to know that they are pinned to either evading or directly confronting that fact.

4. Philosophy, Baroque Critique, and Time

“Those who are employed experience a distinction between their employer’s time and their ‘own’ time”.

E. P. Thompson [

25] (p. 61).

“The temporal relationship imposed by capital only allows the location of an event at a single point”.

Bruno Varela, La ranura en el tiempo (Anáhuac contra los robots) (film from 2024).

Overly cursory explanations of the contexts needed for understanding why anyone would be motivated (bothered, driven, inspired) to express a judgment on some matter about knowledge, reference, wrongdoing, etc., is a general problem in the presentation of examples and thought experiments in contemporary analytic philosophy [

26]. Debates in analytic philosophy of film over the last two decades about whether films can “do philosophy” are, on the whole, no exception to this problem; if understanding films as a medium for philosophical interventions is not to be a theoretical imposition on them, we must understand what the point is of a film’s expressing this judgment, in its culture, in a specific historical moment, and to whom. And yet even in his ground-breaking discussion of experimental cinema’s capacity to make philosophical statements, Noël Carroll only briefly mentions the “communicative context of minimalist art”, in which it would be “more than merely appropriate to expect a film like [Ernie Gehr’s]

Serene Velocity [1970]” to suggest something philosophical about the nature of film [

27] (p. 179). Without much further elaboration, David Davies says, “If the content [of a film] is indeed philosophical, then grasping this will surely require some philosophical contextualisation” [

28] (p. 5). Too often in these discussions, “context” is invoked more as a placeholder than as itself a topic of philosophical interrogation.

It is additionally surprising that, within these debates, making-of documentaries have not been further explored as sites for critiques of the philosophical pretensions of their primary subjects. Thus, for example, Werner Herzog’s vision in Fitzcarraldo (1982) of the power of the individual spirit in wild nature can be unsettled by Les Blank’s exposé in Burden of Dreams (1982) of the exploitative, dangerous labor conditions of the Indigenous workers of Peruvian Amazonia needed to sustain an aesthetic presentation of just that vision. A hypothesis to be explored is that the very reason why analytic philosophers of film have not sufficiently entertained the possibilities of this exposé of production as philosophical critique is that doing so rigorously would raise the very questions of context, especially regarding power (“What is the power of the makers of the original production over the documentary makers?” “Were the latter employed by them?” “Who risks exile, and who is in a position to put others in it?”) that it is the standing tendency of those debates to obfuscate.

An insistence on the context and stage setting needed for a philosophical claim to be intelligible is usually associated with the later Wittgenstein [

29]. And yet a striking analogue can also be found in some formulations of Latin American Marxism. Thus, recently, the Mexican Marxist philosopher Carlos Oliva Mendoza has highlighted a kind of historical ancestor to the context-obfuscating discourse often diagnosed by Wittgensteinians, in his case in the form of “romantic critique”. He associates this older critical discourse, with its close connections to liberalism and Enlightenment rationalism, with the invention of the printing press and the formation of modern states. Thus, romantic critique “is (just nearly) loyally subject to the printing press and the incredible journey around the planet made by books and other reams […], not to mention the much later establishment of newspapers and radio”

16 [

9] (p. 235).

Moreover, for Oliva Mendoza, romantic discourse “is sedimented in the national, state, and even ecclesiastical structure, in a kind of assembly of experts, technicians, and scientists”, which in turn historically shaped its idealist articulations of revolution and justice (“whether proletarian or bourgeois”). Here, the problem is not exactly a fantasy of meaning as communicative or intelligible independent of social and historical context but rather a fantasy of civil society or the press as vehicles of meaningful critique independent of an acknowledgement of their subordination to the dynamics of capitalism, including those that value “capital above any principle of justice”

17 [

9] (p. 236). According to Oliva Mendoza, by denying these dynamics, or rather by pretending to have an external perspective on them, this kind of critical discourse finds its natural home in bureaucracies.

Oliva Mendoza then asks whether an alternative conception of critique is available, and he indeed locates it in “baroque critique”. This is a kind of critique of those same dynamics of capital that rejects any external perspective on them precisely because it is rendered out of their “waste”. Thus, he refers to the “baroque fact wherein consumption is transmuted into waste in the face of accumulation […]. There, the baroque threatens, plays with, and parodies the civil economy of capitalist societies”

18 [

9] (p. 237). This conception of the baroque as parody of the administrative waste of capital derives directly from the Cuban author Severo Sarduy’s proposal that “to be baroque today means to threaten, judge, and parody the bourgeois economy based on the stingy administration of goods, at its very center and foundation: the space of signs, language, symbolic support of society, guarantee of its functioning, of its communication”

19 [

30] (p. 209), [

9] (p. 237).

Sarduy’s formulations explicitly contrast the basis of baroque critique in the waste of capital with fantasies of clear communication inhering in critiques operating outside of that waste: “The baroque space is thus that of superabundance and waste. Contrary to communicative, economical, austere language, reduced to its functionality—serving as a vehicle for information—baroque language delights in the supplementary”

20 [

30] (p. 210). Meanwhile, the Ecuadorian–Mexican philosopher Bolívar Echeverría (an avowed influence on both Oliva Mendoza and Varela) connects the baroque critique’s basis in waste with a revolt against those productions that it turns against and parodies: “It is baroque the way of being modern that gives life to the destruction of the qualitative, produced by capitalist productivism” [

31] (p. 91).

These expressions of the baroque as the creative subversion of capitalist productivism and administration are not far from well-known European formulations of that concept, including even Deleuze’s well-known proposal that the baroque “endlessly produces folds. It does not invent things” [

32] (p. 3). They especially evoke Adorno’s view of the baroque as “

decorazione assoluta, as if it had emancipated itself from every purpose […] and developed its own law of form” [

33] (p. 294)

21. The baroque’s inventiveness is not

productive but rather the internal development of a form derived from elsewhere. And yet these above-mentioned formulations of baroque critique also, in their way, build upon the Cuban author Alejo Carpentier’s 1975 arguments about the peculiarly baroque character of Latin America (“all symbiosis, all

mestizaje, engenders a baroque style”), including his surprisingly transhistorical examples of Oaxaca, where both the pre-Hispanic archaeological site of Mitla and the Hispanic, Dominican Church of Santo Domingo count as “baroque” [

35] (p. 21)

22. For Carpentier, baroque

mestizaje operates in the very mixture of examples.

We do not need to go as far as Carpentier’s arguments in order to understand exactly how Bruno Varela’s Papeles Secundarios and Cuerpos Complementarios constitute “baroque critiques” emerging from Oaxaca. Varela refuses to take an external, “romantic” perspective on the extractivism involved in “plantation cinema”, and instead re-orders its administrative waste, the detritus of a foreign production in that region. (The relation is doubled in Cuerpos Complementarios, where the detritus is additionally derived from Papeles Secundarios and its participation in elite exhibition circuits.) The provocation offered by Varela is that this may be the precise and only way of making a people present on film.

On the other hand, Varela’s work does contribute to the view, articulated by another Cuban author, José Lezama Lima—and quoted by Bolívar Echeverría—of the baroque as an art of the “

contraconquista”

23 [

37] (p. 80). It is an aesthetic resource brought out and emphasized in the Spanish conquest of the Americas (for example, the Mexican scholar and artist Mariana Botey speaks of the idea that “in Spanish America, the machine of colonization is a baroque machine”

24 [

38] (p. 38)), which ironically presents the possibility of being turned against colonizers just because it insists on leaving the waste of colonial administration, including in some cases features of the workday, unburied or at least partially unburied. The baroque is a manifestly worked-upon aesthetic. Thus, any kind of appeal to justice for a working people (like what Oliva Mendoza calls “romantic critique”) that bypasses the communicative powers of such left-behind waste—that seeks to clear to it away—risks obfuscating the very

people in question.

It is then possible to begin understanding Varela’s complex relationship with the above-mentioned “cliché” about the invisibility of labor in cinema. Strikingly, Varela’s films are less direct than Azari’s María de los Ángeles (where we hear Azari specify to the titular character three filming days, lasting all day) in capturing the real routines of the workday on the set of Tooba. But Varela’s work is motivated by a suspicion about whether the fantasies surrounding such clear documentation could ever amount to a critique, particularly without the preparation and stage setting involved in the playful re-arrangement of waste.

By not only working with the detritus of Neshat’s production but also locating his baroque critique in those moments of leisure in which the workers “leave the factory”,where his filmmaking and the cast’s playful dancing with masks are regarded as two aspects of the same ludic activity, Varela reveals the special powers of an elliptical representation of the workday on the set of

Tooba. The workday is not directly represented in these films, but rather emerges, “visible” from the corners of that play with waste. In a pertinent discussion of non-professional acting, Elena Gorkinkel says that such labor “makes itself visible by virtue of its capacity and inclination, at any moment, to stop working, to not work” [

39] (p. 96). This view need not amount to the cliché that something only emerges in its absence: at least on Varela’s rendering, it is the view that work can become visible thanks to re-arranged detritus of the workday, but only once that workday ends.

The reason for this has centrally to do with time. As quoted above, in a recent project, Varela says that “The temporal relationship imposed by capital only allows the location of an event at a single point”. The implicit contrast he is making is with playful experiences of being wrested from our normal temporal coordinates, for example, through re-arranging old or archival footage. The temporal relationship imposed by capital in the workday is inimical to the

temporal athleticism required for baroque critique. Thus, for this very reason, the entire body of Varela’s anti-capitalist cinema is heavily integrated with references to science fiction and time travel, from Chris Marker to Philip K. Dick [

40,

41,

42]. That is, the workday produces the waste and conditions for baroque critique, but only for

outside the workday. This is because the workday is, obviously, instrumental and forward-looking; it can come to an “end” either in the sense of reaching a certain hour, or when a designated task is finished. But baroque critique, in its aspects of parody and re-arrangement, operates by

going backwards and giving new form to waste left during production, during the workday. It is the critique that, against the sense of capital, goes back to the job that the employers had considered finished.

Thus, the question of time in Varela’s critique of Tooba goes deeper than his using the detritus of the latter’s production in order to reveal the workday of its non-professional actors. Neshat’s film displays pretensions of communicating sanctuary and transcendental experience, including trans-temporality, as emphasized in its looped presentations in galleries, which might additionally have influenced Azari’s conception in María de los Ángeles of the original film as a refuge to which its titular character can always return. (Perhaps Dabashi would regard these aspects—Tooba as itself a continually looping sanctuary—as the temporal registers of Neshat’s “universal concerns”.) Varela’s work embraces some of those same notions but is additionally committed to the idea that communicating them must be earned, that is, rooted in a temporal flexibility and play that is unintelligible outside of release from the regimentation of the workday. A critique of Tooba that turned simply on exposing the workday of a people would be limited by the fact that Neshat’s film has no pretensions of representing a defined “people”, whether in Oaxaca, in Iran, or elsewhere. But Varela’s baroque critique ultimately rests on the idea that, for this very reason, the trans-temporal sanctuary promised in the film feels—at least for one artist involved in its production—abstract or idealist, an unprepared-for utterance hanging in the air.

Varela’s critique of Tooba therefore contributes to a wider idea of baroque trans-temporality in film: it is a way of escaping the regimentation of the workday without being detached from that context precisely because it is the playful re-ordering of the workday’s waste. It is a communication of temporal flexibility that is manifestly worked-upon.

5. Conclusions: The Materially Grounded Trance

Of course, Varela’s attempts to recover the people missing from Neshat’s Tooba, and thereby expose as idealist the transcendental experience or sanctuary at the center of the film, do not engage with the latter’s sources in the Quran or in Shahrnush Parsipur’s writing. He belongs to a context in which those sources are not in currency.

But in proposing that

Papeles Secundarios and

Cuerpos Complementarios offer a counter-vision of people-sustaining trance grounded in the material exigencies of the workday and in the material waste of capital, I do mean to place these works in dialogue with those invocations of the Deleuzian trance that, as I mentioned at the beginning of this essay, are highly current in contemporary Latin American experimental cinema. Thus, we find in the opening of the “Thesis on the Audiovisual”, a 2021 manifesto by the Tehuacán, Puebla-based Colectivo Los Ingrávidos (the most internationally successful collective in the history of Mexican experimental cinema): “In the [political cinema of agitation], agitation no longer emerges from new awareness nor calls for mass mobilization, but rather consists of putting everything in a trance [so that it] produces collective audiovisuals of the

Missing People” [

5]. This vision of the trance understands it as manifesting unique people-sustaining or people-producing powers, ones unavailable to “romantic critique” and its calls for revolution and justice (“whether proletarian or bourgeois”, as Oliva Mendoza put it).

This highly compelling, often ingenious statement of the collective’s “Shamanic Materialism” even obliquely touches on the baroque in the form of the “funerary trance” as a figure for the appropriation of waste: “One of the forms of the political cinema of agitation is the cinema of appropriation, which implies an aberrant sensory practice. The liturgical dimension of this aberration is burial […]. The burial of images and sounds is the kinetic trance of the appropriated audiovisual document” [

5]. But this materialist statement ironically confesses its own elements of schematic formalism when it says “In the political cinema of agitation there are three

forms of the People: The Supposed People, the Missing People and the Population”

25 [

5]. More concretely, we come to understand in a footnote that the latter term refers to kinds of bureaucratic atomization: “a mass that [corporate governments] can administer, quantify, manage”. Thus, according to Los Ingrávidos, “official discourse” transforms “the Missing People and the Supposed People into a Population” [

5].

Individuals can always and easily be filmed. But until filmmakers have labored through the exigencies of what it means to demonstrate a workday, however elliptically, however baroquely, no people has made it on film. The lesson of significant recent experimental filmmaking in Mexico is that pretensions to trans-temporality or transcendental experience can indeed be the resource that Deleuze recognized in his writing on the trance, but only so long as it is guided by the counter-temporality of the workday.