The Necessity and Goodness of Animals in Sijistānī’s Kashf Al-Maḥjūb

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. The Kashf and Its Author

- Discourse One: On Unity (tawḥīd)

- Discourse Two: On Recalling the First Creation [the Intellect]

- Discourse Three: On the Second Creation [the Soul]

- Discourse Four: On the Third Creation, namely Nature

- Discourse Five: On the Fourth Creation [sublunary creation]

- Discourse Six: On the Fifth Creation [Prophethood—Imamate]

- Discourse Seven: On Mentioning the Sixth Creation [the Resurrection and return]

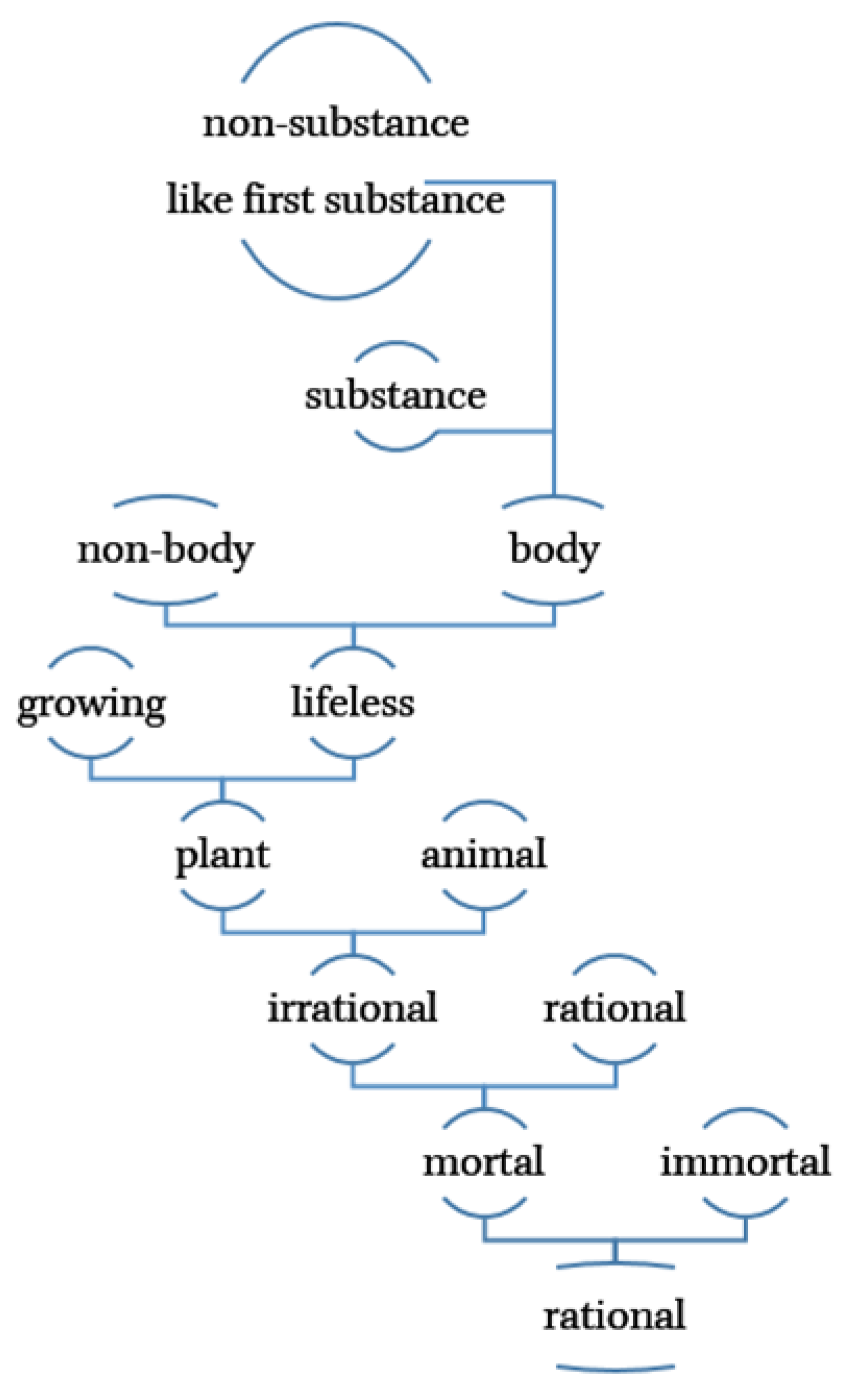

3. Animals in the Cosmic Order

4. Animal Motion

5. Animal Benefits

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Passages on Animals from the Kashf

Appendix A.1. Manuscript Description

| In the Margin of the Given MS. | Subscribed ḥā | حMS [word] |

|---|---|---|

| On the top of the indicated word (“[word]”) in the given MS. | Subscribed fawq | فوقMS [word] |

| Corrected by the scribe in the margin | Subscribed ṣḥ | صحMS [word] |

| Alternative word for “[word]” offered by the scribe | Subscribed kh | خMS [word] |

| The “[word]” in the given MS. is not legible | Subscribed nākhwānā | ناخواناMS [word] |

| The “[word]” is absent from the given MS. | M-dash | —: MS [word] |

| In the given MS. the “Phrase” comes after the “[word]” | Phrase+: MS [word] | |

| “||” separates multiple occurrences of the same word in a paragraph | Word || Word | |

| Crossed out by the scribe | ||

| Word1 is crossed out by the scribe and replaced with word2 | word2 ← |

Appendix A.2. Edition and Translation of Kashf al-maḥjūb

| Discourse I: On the Unity | مقالتِ اوّل: در توحید |

| Discourse II: On Bringing to Mind the First Creation [Intellect] | مقالتِ دوم: در یاد کردنِ خَلقِ اوّل [= خِرَد / عقل] |

| Discourse III: On the Second Creation [Soul] | مقالتِ سوّم: اندر خلقِ ثانی [= نفس] |

| Discourse IV: On the Third Creation, namely Nature | مقالتِ چهارم: در خلقِ ثالث و آن طبیعت است |

| Discourse V: On the Fourth Creation [the types of Existents; Metempsychosis] | مقالتِ پنجم: در خلقِ رابع [= موجوداتِ روی زمین—تناسخ] |

| Discourse VI: On the Fifth Creation [Prophethood, Imamate] | مقالتِ ششم: در خلقِ خامس [= پیغمبری—نبوّت—امامت] |

| Discourse VII: On Mentioning the Sixth Creation [the resurrection] | مقالتِ هفتم: در ذکرِ خلقِ ششم [= معاد—قیامت] |

| I. 1: On removing thingness from the Creator | جستارِ اوّل: در دور کردنِ چیزی از آفریدگار |

| I. 2: On removing limit from the Creator | جستارِ دوم: در دور کردنِ حدّ از آفریدگار |

| I. 3: On removing attributes from the Creator | جستارِ سوّم: در دور کردنِ صفات از آفریدگار |

| I. 4: On removing place from the Creator | جستارِ چهارم: در دور کردنِ مکان از آفریدگار |

| I. 5: On removing time from the Creator | جستارِ پنجم: در دور کردنِ زمان از آفریدگار |

| I. 6: On removing being from the Creator | جستارِ ششم: در دور کردنِ هستی از آفریدگار |

| I. 7: On removing the opposites of these terms from the Creator [against taʿṭīl and tashbīh] | جستارِ هفتم: در دور کردنِ آنچ برابرِ این لقبها اُفتد از آفریدگار |

| II. 1: On the meaning of the [statement that] intellect is the center of both worlds | جستارِ اوّل: در معنیِ آنک خرد مرکزِ دو جهان است |

| II. 2: That intellect becomes one with the command of God which is expressed ascommand to oneness | جستارِ دوم: در یکی شدنِ خرد به اَمرِ ایزد کی عبارت از امر به وحدت کنند |

| II. 3: That intellect becomes one with the Command of God which is expressed asCommand to the Word | جستارِ سوّم: در یکی شدن خرد با اَمرِ ایزد کی عبارت از امر به کلمه کنند |

| II. 4: That intellect becomes one with the command of God which is expressed as a command to knowledge | جستارِ چهارم: در یکی شدن خرد با اَمرِ ایزد کی عبارت از امر به علم کنند |

| II. 5: On the meaning of Intellect’s becoming one with the command of God which is expressed as command to the command in itself (amr beh nafs-e amr) | جستارِ پنجم: در معنیِ یکی شدن خرد با اَمرِ ایزد کی عبارت از امر به نفسِ امر کنند |

| II. 6: How the seed of both worlds is in intellect | جستارِ ششم: در چگونگیِ آنک تخمِ دو جهان در خرد است |

| II. 7: How the conjoining of intellect with soul [takes place] | جستارِ هفتم: در چگونگیِ جفت گشتنِ خرد با نفس |

| III. 1: That the Soul has descended in the form of man | جستارِ اوّل: در آنک نفس به صورتِ مردم فروآمده |

| III. 2: That the motion of soul collects/gathers all motions | جستارِ دوم: در آنک حرکتِ نفس گردآور همۀ حرکات است |

| III. 3: Knowing the division of plant within the Soul | جستارِ سوّم: در شناختنِ بخشِ نبات از نفس |

| III. 4: Knowing the share of the animal in Soul | جستارِ چهارم: در شناختنِ بهرِ حیوان از نفس |

| III. 5: How sense perception depends on the sensory perceiver which is the soul | جستارِ پنجم: در چگونگیِ بازگشتنِ حسّ به حاسّ و آن نفس است |

| III. 6: How discourse (noṭq) depends on the speaker, which is the soul | جستارِ ششم: در چگونگیِ بازگشتنِ نطق به ناطق و آن نفس است |

| III. 7: How thought depends on the thinker, which is the soul | جستارِ هفتم: در چگونگیِ بازگشتنِ فکرت به تفکّر و آن نفس است |

| IV. 1: That the beings can be perceived through Nature | جستارِ اوّل: در آنک هستیها به طبیعت در توان یافت |

| IV. 2: That Nature does not change its state | جستارِ دوم: در آنک طبیعت از حالِ خویش بِنَگردَد |

| IV. 3: That natural forms are not posterior to the natural principle | جستارِ سوّم: در آنک صورتهای طبیعی نه از پستر است از اصلهای طبیعی |

| IV. 4: That the center of nature is closer to neighboring upon the spiritual realm | جستارِ چهارم: در آنک مرکزِ طبیعت سزاوارتر است به همسایگی کردن با روحانیان از آفاق |

| IV. 5: How nature receives assistance from the Soul | جستارِ پنجم: در چگونگیِ مدد کشیدنِ طبیعت از نفس |

| IV. 6: That the beauty of nature, namely the adornment of nature, is spiritual | جستارِ ششم: در آنک زینتِ طبیعت یعنی آرایشِ طبیعت روحانی است |

| IV. 7: That composite, generated things emerge from the “mothers” (i.e., elements) and “fathers” (i.e., celestial spheres) through God’s providence | جستارِ هفتم: در آنک موالید از اُمّهات و آباء ظاهر نشود مگر به تدبیر ایزد |

| V. 1: That the species are preserved | جستارِ اوّل: در آنک انواع نگاه داشته است |

| V. 2: That Animals did not appear after Plants | جستارِ دوم: در آنک حیوان نه از پسِ نبات پدید آمد |

| V. 3: That the species do not mix with each other, neither at composition, nor after composition | جستارِ سوّم: در آنک انواع با یکدیگر درنیامیزند، نه در ترکیب و نه پس از ترکیب |

| V. 4: That not one of the Species is destroyed, and none is added | جستارِ چهارم: در آنک انواع یکی باطل نگردد و یکی افزون نشود |

| V. 5: That the increase and decrease of existing individuals does not entail either growth or decrease in virtues | جستارِ پنجم: در آنک بسیاری و کمیِ افراد در فضایل افزونی و کمی نیارد |

| V. 6: That the circular motion, namely spherical motion, is the cause of animal motion | جستارِ ششُم: در آنکحرکتِ مُدوّر یعنی جُنبِشِ گِرد علّت حرکاتِ حیوانات است |

| V. 7: That the number of species is limited | جستارِ هفتم: در آنک انواع معدود است |

| VI. 1: How the prophethood of the Prophets is facilitated | جستارِ اوّل: در چِگونگیِ سَبُک گشتنِ پیغمبریِ پیغامبران |

| VI. 2: On the dominion of the prophet over speech (sokhan) and the rhetoricians (ahl-e sokhan) | جستارِ دوم: در غلبه کردنِ پیغمبری سخن را واهلِ سخن را |

| VI. 3: On why the later prophet confirms the veracity of the former prophet | جستارِ سوّم: در علّتِ راستگوی داشتنِ پیغمبرِ پسینْ پیغمبرِ پیشین را |

| VI. 4: On why the former prophet spreads the joyful news of the future prophet | جستارِ چهارم: در علّتِ بشارتِ پیغمبرِ پیشین پیغمبرِ پسین را |

| VI. 5: That the proof of God is not established by a single prophet | جستارِ پنجم: در آنک به یک پیغمبر حجّتِ خدای بر پای نشود |

| VI. 6: On the meaning of the attribution of “descent” to Jesus [alone] among all the prophets | جستارِ ششم: در معنیِ نسبتِ فروآمدن به عیسی از میانِ همۀ پیغمبران |

| VI. 7: On the meaning of the attribution of Lord of Resurrection to the Mahdī | جستارِ هفتم: در معنیِ نسبتِ خداوندِ قیامت به مهدی |

| VII. 1: That resurrection is a peer of existence | جستارِ اوّل: در آنک برانگیختنْ قرینِ بودن است |

| VII. 2: That supposing multitude [of all living beings] to be resurrected is contrary to the truth | جستارِ دوّم: در آنک اندیشه در بسیار برانگیختن خلافِ حقّ است |

| VII. 3: That the knowledge of the resurrection is veiled from the soul | جستارِ سوّم: در آنک معرفتِ برانگیختنْ در حجاب است از نفس |

| VII. 4: That the resurrection is the discipline of the soul | جستارِ چهارم: در آنک برانگیختنْ ریاضتِ نفس است |

| VII. 5: That due to resurrection, the ill-fated may become well-fated, and the well-fated may become ill-fated | جستارِ پنجم: در آنک از بهرِ برانگیختنْ بدبخت نیکبخت گردد و نیکبخت بدبخت شود |

| VII. 6: On the length and shortness of the duration of the resurrection | جستارِ ششم: در درازی و کوتاهیِ مدّت برانگیختن |

| VII. 7: That regarding the resurrection, good deeds are of greatest benefit | جستارِ هفتم: در آنک کارهای نیک بزرگتر منفعتیست برانگیختن را |

| 1 | We express our gratitude to Hamed Arezaei for helping us access MS Mīnovī 2857, MS Adabiyāt 194jīm, MS Dāneshgāh-e Tehrān 8798, and MS. Malek 4055-2. Further, we extend our gratitude to Fateme Mehri for reviewing a previous draft of the edited passages and providing valuable insights. |

| 2 | For the sake of brevity, we omitted the differences in the footnotes to save space; however, we retained the divergences in words and expressions that include kay/kih/keh, such as ān-kay/ān-keh or azīrāk/azīrākeh. |

| 3 | [کی] کر: که |

| 4 | [آفریدگار است] اد: آفریدهکار است / دت: آفریدهگارست |

| 5 | [یا] کر: <یا< / می: —، میح: یا / مج، اد، دت، مل: — |

| 6 | [نفس با خرد] مج، مل: خرد با نفس / |

| 7 | [کی] کر، می: که / مج، اد، دت: کی |

| 8 | [کی] کر، می، مج: که / مج، اد، دت: کی |

| 9 | [این چُنان] مج: آن چنین / مل: اینچنین |

| 10 | [گه] دت: گاه، دتفوق: که |

| 11 | [را] مج، مل: — |

| 12 | [پس] مج، مل: — |

| 13 | [جسم و روح] مج، مل: روح و جسم |

| 14 | [کی] اد، دت: که |

| 15 | [و] می:—/ مج، مل: +آن |

| 16 | [آنک] مج، مل: آنکه |

| 17 | [تمییز] مجناخوانا، مل: تمیز |

| 18 | [بهر] مج، مل: بابت |

| 19 | [ملائکه] می: ملایکه / مج، مل، اد: ملئکه / دت: ملاءکه |

| 20 | Here nabāt, which often means “plant”, is used in its original meaning of that which grows, so it includes both animals and plants. |

| 21 | [کی] مج، مل: — |

| 22 | [به] مج، مل: با |

| 23 | [دو] مج، مل: بدو |

| 24 | [و] مج، مل: — |

| 25 | [بھری ناطق و بھری غیرِ ناطق] مج، مل: ناطق و غیر ناطق |

| 26 | [و غیرِ ناطق] مل: — |

| 27 | [پَراکندهها] کر: پراکندها / می، اد: براکندها / مج، مل: پراکندکیها / دت: براکندهها |

| 28 | [زیراک] مج، مل: زیرا کی |

| 29 | [مردم است] اد: مردمست |

| 30 | [در] دت: ء، دتفوق: در |

| 31 | [بهر است] کر، می، مج، مل: بهرست / اد، دت: بهر است |

| 32 | [زیراک] مج، مل: زیرا کی |

| 33 | [بهر] مج، مل: — |

| 34 | [زیراک] مج، مل: زیرا کی / اد: زیرا |

| 35 | [حسّی و ... زیراک زندگانی] دت: —، دتح: حسّی و ... زیراک زندگانی / [زندگانی] مج، مل: نفس زندگانی |

| 36 | [آنک] مج، مل: آنکی |

| 37 | [اندر] مج، مل: در |

| 38 | [طبیعت است] مج: بطبیعتست / مل: بطبیعت |

| 39 | [ازین] مج: از این |

| 40 | [جهت] اد: جهة |

| 41 | Corbin and Landolt translate as “quintessence”. Corbin explains the meaning of the words lobb and maghz as follows: “The heart, marrow, nucleus, or innermost substance of a thing”. |

| 42 | [یافت] مج، مل: گرفت |

| 43 | [پذیرفتن] دت: بردن، دتفوق: پذیرفتن |

| 44 | [موالید] اد: مولید |

| 45 | [فایدهای] کر: فایدهئی / می: فایده𞸃 / مج، دت، دا، مل: فایده |

| 46 | [نبات] مج، مل: +و |

| 47 | [فایدهای] کر: فایدهئی / می: فایده𞸃 / مج، دت، دا، مل: فایده |

| 48 | [گیاهها و میوهها] کر، می: گیاها و میوها / میح: کذا / مج، دت، اد: گیاها و میوهها |

| 49 | [دادن] دت: یافتن، دتفوق: دادن |

| 50 | [پذیرفتن] دت: بردن، دتفوق: پذیرفتن |

| 51 | [را] مج: — |

| 52 | [پذیرفتن] مجح، ملح: +و دادن با نبات «احتمال دارد این عبارت در اصل ساقط شده» |

| 53 | [دادن] مج، مل: پذیرفتن و دادن |

| 54 | [قبل] مل: قبیل |

| 55 | [را] مج: از بهر حرکت |

| 56 | [است] مج، مل: — |

| 57 | [زندگانی] دت: زندگی، دتفوق: زندکانی |

| 58 | [طبیعی] مج، مل: +ست |

| 59 | [کسب] اد: سبب |

| 60 | [فاعرفه] اد: — |

| 61 | [در] کر، می، اد، دت:—/ مج، مل: در |

| 62 | [از آن] کر: از / می، مج، اد، دت: از آن |

| 63 | [نبینی] مج، مل: و نیست |

| 64 | [یکدیگر] کر، می: یک دیگر |

| 65 | [چون دوست داشتنِ لونهای نیکو و رویهای نیکو بود بصر را؛ و غلبتِ بصر] مج: — |

| 66 | [نفس] مجصح، مل: +نکاه |

| 67 | [شمّ] دت: نسیم ← دتفوق: شمّ |

| 68 | [خوش] کر، می، دت، دا:—/ مج، مل: +و |

| 69 | [بگُوارانیدن] می: نکوارانیدن |

| 70 | [حَرب] اد: +کردن |

| 71 | [آن] مج، اد، مل: از / دت: — |

| 72 | [از نفس] مج، مل: ان نفس را |

| 73 | [بیم] دت: —، دتفوق: بیم |

| 74 | [زیراک] دا: زیرک |

| 75 | [حیوة] دت: حیات / اد: حیوات |

| 76 | [صنعت] اد: طنعت |

| 77 | [آن] کر: این |

| 78 | [رنگهای آن] مل: رنگها وان |

| 79 | [مُشاکل است] کر: مشاکلست / اصل (کر)، می، مج، اد، دت، مل: مشاکلت |

| 80 | [روحانی] مج: جسمانی، مجفوق: روحانی / ملفوق: جسمانی |

| 81 | [نبینی] مج، مل: ببینی / [مشاکلت او ... نبینی، ... و نه معدنی،] کر: مشاکل است او به جوهرِ روحانی. نبینی ... و نه معدنی؟ |

| 82 | [ولیکن] مج: ولکن |

| 83 | [آنچ] مج، مل: آنچه |

| 84 | [آنک] مل: انکه |

| 85 | [نگاه داشته] مل: نگاهداشته |

| 86 | [کی] مل: که |

| 87 | [نگاهداشت] مل: نگاهداشت |

| 88 | [نگاه داشتن] مج، مل: نگاهداشت |

| 89 | [زَبَر] می: زیر، میح: زبر / مج: زبر / مل: در زیر |

| 90 | [زیراک] مل: زیرا که |

| 91 | [گشتن] اد: شدن |

| 92 | [دو] میناخوانا: رو / دتفوق: ی |

| 93 | [کی] مل: که |

| 94 | [نگاه دارد] مل: نگاهدارد |

| 95 | [نگاه داشته] مل: نگاهداشته |

| 96 | [واجب است] اد: وجبست |

| 97 | [جهت || جهت || جهت] اد، دت: جهة || جهة || جهة |

| 98 | [بلک] مل: بلکه |

| 99 | [نگاه داشته] مل: نگاهداشته |

| 100 | [بسیار است و آن یک نوع است؛ مثل] کر: بسیارست، و آن یک نوع است مثل |

| 101 | [ایدونک] مل: ایدونکه |

| 102 | [بر] دت: در، دتفوق: بر |

| 103 | [آنچ] مج: آنچه |

| 104 | [آنچ] کر: آنچه / می: آنچ / دت: آنک، دتفوق: نچ |

| 105 | [امّا] دت: و امّا |

| 106 | [آنچ] مج: آنچه |

| 107 | [آنچ] مج: آنچه |

| 108 | [آنک] مج: آنکی |

| 109 | [نه] مج، اد، دت: — |

| 110 | [اثر هم از آن اصل] مل: ازهم از آن اصل |

| 111 | [در آفرینش بر فصلِ اوّل اند، از بهرِ آنک این اثر از آن شعاعاتِ صورتهای فلکی پذیرند] مل: — |

| 112 | [نگاه دارنده] مل: نگاهدارنده |

| 113 | [چیز کی || آنک || زیراک || کی در || آنک] مل: چیزیکه || آنکه || زیرا که || که || در || — |

| 114 | [را] کر، می، مج، اد، دت، مل: — |

| 115 | [پیش ... پیش] می، اد، دت: بیش ... بیش |

| 116 | [خواستیم] مج: خواستم |

| 117 | [کی] مج:—/ [کی] مل: — |

| 118 | [درین] مج، مل: در این |

| 119 | [آنچ] مج، مل: آنچه |

| 120 | [همه چیزها] مج: + همه چیزها |

| 121 | [پیش] می، اد، دت: بیش |

| 122 | [باید] مج، مل: آید |

| 123 | [همچنانک] مج: هم چنانک |

| 124 | [مدبّر] مل: بر |

| 125 | [کزان] کر: کز آن / می، مج، دت، اد، مل: کزان |

| 126 | [و این] دت: و ان ← و این |

| 127 | [باید] اد: بایست |

| 128 | [پیش] می، دت، اد: بیش |

| 129 | [کی] مل: — |

| 130 | [از] مج: — |

| 131 | [دربودن] کر: و بودن / اصل (کر): ودبوذن / می، اد، دت: وبوذن / مج، مل: و دربودن |

| 132 | [آن] اد: ان آن |

| 133 | [آمدن] می: آمذان، میح: کذا فی الأصل / مج: آمدان / اد، دت: آمذ آن / مل: آمد آن |

| 134 | [همچنانک || زیراک || گویند کی || ایدونک || ایدونک] مل: [همچنانکه || زیرا که || گویند || ایدون که || ایدونکه] |

| 135 | [به بودن] کر: >بر> بودن / می: بودن / مج، اد، مل: ببودن / دت: — |

| 136 | [پیشتر || پیشتر|| پیشتر || پیشتر || پیشتر || پیشین] می، اد: بیشتر || بیشتر || بیشتر || بیشتر || بیشتر || بیشین |

| 137 | [بکردند] اد: نکردند |

| 138 | [فلک] مل: انکه |

| 139 | [بیشتر || پیشتر] می، اد: بیشتر || بیشتر / کر، مج: بیشتر || پیشتر |

| 140 | [شد] اد: باشد |

| 141 | [فراپیش] دت: آفرینش ← فراپیش |

| 142 | [قوت || قوت || قوتها || قوت || قوت || قوت] اد: قوّت || قوّت || قوّتها || قوّت || قوّت || قوّت / دت: قوّت || قوّت || قوّتها || قوّت || قوت || قوّت |

| 143 | [پیشتر] می، مج، اد، دت: بیشتر / |

| 144 | [زیراک] مج: زیرا کی / مل: [زیرا که] |

| 145 | [کند] مل: کنند |

| 146 | [و گرد همی کند] مج، مل: — |

| 147 | [باز] مج: باو |

| 148 | [آن چیز است] دت: انست ← آنچیزست |

| 149 | [پیشهها || پیشهها] کر: پیشها / می: بیشها / مج، مل: پیشهها / اد، دت: بیشهها |

| 150 | [علمی است] مج، مل: علمست |

| 151 | [از] کر: از / می، مج، اد، مل: — |

| 152 | [زیراک || آنک] مل: [زیراکه || آنکه] |

| 153 | [است] مج، مل: — |

| 154 | [بردن] دت: بوذن ← برذن / [شغل بردن] مل: مشغول بودن |

| 155 | [آنچ] مج، مل: آنچه |

| 156 | [ننهادند] می، اد: بنهادند / دت، مل: نهادند |

| 157 | [درست شد ... نبات بود.] اد: پس درست شذ کی قول آنان کی کفتند کی حیوان از بس نبات بدیذار آمد ناروا بوذ و ایشان را بر این قول برهانی نباشذ تا ببرهان ثابت کنند بس این درست بوذ کی حیوان نه از بس نبات بوذ |

| 158 | [یکدیگر] مج، مل: یکدیگر |

| 159 | [زیراک] مج: زیرا کی / مل: زیرا که |

| 160 | [درآمیختی] مل: درآمیختن |

| 161 | [جایز بودی ... با یکدیگر] مل: — |

| 162 | [مردمی] دت: مردم، دتفوق: می |

| 163 | [شد] مج: شده |

| 164 | [یکدیگر ... یکدیگر ... یکدیگر ... یکدیگر] مج، اد، دت، مل: یکدیگر |

| 165 | [درنیامیزند] دت: نیامیزند، دتفوق: در |

| 166 | [دیگر] اد: +کی |

| 167 | [آن] دت: —، دتفوق: آن |

| 168 | [پنداشتند] اد: بیذاشذند |

| 169 | [گروه اند] اد، مج: گروهند |

| 170 | [به تناسخ] اصل (کر): نتناسخ |

| 171 | [منسوب اند] مج: منسوبند / اد: +کی گویند |

| 172 | [سگ و خر] دت: خروسک |

| 173 | [سگ] مل: یک |

| 174 | [درو] اد: در او |

| 175 | [صورتِ سگ درو مقدور است] مج، مل: جز صورت سگ درو مقدور نیست |

| 176 | [بود] دت: شد، دتفوق: بود |

| 177 | [هرچه آن] مج، مل: هرانچه |

| 178 | [بایست] اد: باید / مل: بست |

| 179 | [آنک] مج، مل: — |

| 180 | [آنگه کی] مل: انکه |

| 181 | [درآمیختن] کر: در آمیختن |

| 182 | [با یکدیگر] مج، مل: بیکدیگر / اد، دت: با یکدیگر |

| 183 | [مردمان] دت: مردم، دتفوق: مان / |

| 184 | [گناهکاران ... گناهکاران] مج: کناه کاران ... کناهکاران / می، اد: کناه کاران ... کناه کاران |

| 185 | [زیراک] مل: [زیرا که] |

| 186 | [بسیار اند] می، مج، اد، دت، مل: بسیارند |

| 187 | [را] مج، اد، مل: — |

| 188 | [اندازهای] مج، مل: اندازه |

| 189 | [و آن فلکها] می، اد، دت، مل: وآن فلکها / مج: وان فلکها / کر: و آن فلکها>ست< |

| 190 | [بلکی] مل: [بل که] |

| 191 | [یکدیگر] اد، دت: یکدیگر |

| 192 | [بعد] مج، مل: پس |

| 193 | [آنک] مل: آن که |

| 194 | [چیز را] مل: چیزیرا |

| 195 | [نتواند] مل: تواند |

| 196 | [بدانک || بدانک] مل: بدانکه || بدانکه |

| 197 | [حیوان] مج، مل: +از |

| 198 | [همی] مج، مل: — |

| 199 | [شود] مج، مل: شوند |

| 200 | [بود] مل: بوند |

| 201 | [حیوان را] می، مج، اد، دت، مل: حیوان را / کر: حیوانانرا |

| 202 | [مستقیم ... مدوّر] اد: مدوّر ... مستقیم |

| 203 | [آنک || ایدونک || بل کی] مل: [انکه || ایدون که || بل که] |

| 204 | [پس چون حرکتِ حیوان به هر سو بود،] مج، مل: — |

| 205 | [حرکات] مج، مل: حرکت |

| 206 | [مانندۀ] مج، مل: مانند |

| 207 | [زیراک] دت: زیرا که |

| 208 | [ظاهر است] اصل (می): ظاست |

| 209 | [کاوّل] مج: کی اوّل / [زیراک || کاوّل] مل: زیرا که || که اوّل |

| 210 | [آن] مل: — |

| 211 | [<نـ>ـبود] کر، می، مج: بوذ / اد، دت: بود If we read jozʾ (particle or part) instead of joz (but, different from)—assuming that the Hamza is dropped from the end of jozʾ— then we get the same sense without amending bovad to nabovad: “its initial point is its last part” (ke-avval-e ān jozʾ-e akhar-e ān bovad). |

| 212 | [ازو] مل: آزاد |

| 213 | If read as “از میانِ حرکتِ اوّل و از میانِ حرکتِ آخر” (az miyān-e ḥarakat-e avval va az miyān-e ḥarakat-e āḫar), namely with two ezāfas in each nominative chain, then we get, “one cannot distinguish [think of] the middle of the initial motion from the middle of the final motion”. However, if we do not read ḥarakat as a further second term of two ezāfas with avval and āḫar as their third terms, namely if we read both occurrences of ḥarakat with sukūn (az miyān-e ḥarakat avval va az miyān-e ḥarakat āḫar), then: “one cannot distinguish between [think of] an initial point in the middle motion and a final point in the middle motion” (which stands in translation). |

| 214 | [ظاهر است] اصل (می): ظاست |

| 215 | [توان] اد: +ثابت |

| 216 | [کی] مج، مل: — |

| 217 | [خُرشید ... خُرشید] مج، مل: خورشید ... خورشید |

| 218 | [آنک] مج: انکی / مل: انکه |

| 219 | [آیند] مج، مل: آید |

| 220 | [جهت] اد: جهة / [ازین جهت] مل: اراینجهت |

| 221 | [خامس] مل: خاص |

| 222 | [چیزی] مج، مل: چیز |

| 223 | [درو] مج: در او |

| 224 | [کی] مج، مل: یکی |

| 225 | [مردم] مج:—/ [کی مغزِ حیوانْ مردم ناطقِ زنده است] مج: یکی مغز حیوان ناطق زنده است |

| 226 | [کار] مل: کارها |

| 227 | [برگُذَشت] مج، مل: بکذشت |

| 228 | [لیکن] مج، مل: لکن |

| 229 | [سخنهای] دت: سخنها |

| 230 | [برانند] مج، مل: برایند |

| 231 | [زنند] مل: نزنند |

| 232 | [رانند] مل: دانند |

| 233 | [آن کی || آنک] مل: [انکه || انکه] |

| 234 | [چِگونگیای] کر: چِگونگیی / می: چِکونکئی / مج، اد، دت، مل: چکونکی |

| 235 | [ازیرا کی] مج: زیراکی / مل: زیرا که |

| 236 | [ کارکردنهایی است] مج: کارکردنهاییست / کر، می، دت: کارکرد نهایتیست / اد: کارکرد نهایتی است / مل: کارکردن نیست |

| 237 | [قصد] اد: — |

| 238 | [جهت] اد: جهة |

| 239 | [شوقی] مجح، مل: +نباشد |

| 240 | [درنخورَد] مجفوق-ناخوانا: بان / مل: +بان ا |

| 241 | [کی]مل: که |

| 242 | [از] مل: — |

| 243 | [هیأتی] اد: هیئتی |

| 244 | [آن] مج، اد، مل: از |

| 245 | [برکتهای] مل: برکتها[کی]مل: که |

| 246 | [و چنین گفتند] مج:—/ اد: و دیکر کفتند |

| 247 | [جا] اد: جای |

| 248 | [کی] اد: یعنی |

| 249 | [دشواری] اد: درشتی |

| 250 | [معنیِ] اد: — |

| 251 | [اومید] مج: امید |

| 252 | [ازین] مج، اد: از این |

| 253 | [مقالتِ ششم، جستارِ هفتم ... و حکمت و کشفِ حقایق.] مل: — |

References

- Roloff, D. Plotin: Die Großschrift; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1970. [Google Scholar]

- Elsas, C. Neuplatonische und Gnostische Weltablehnung in der Schule Plotins; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Narbonne, J.-M. Plotinus in Dialogue with the Stoics; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, P. Freedom, Providence, and Fate. In The Routledge Handbook of Neoplatonism; Slaveva-Griffin, S., Remes, P., Eds.; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2014; pp. 437–452. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, C.I.; Powers, N.M. Creation and Divine Providence in Plotinus. In Causation and Creation in Late Antiquity; Marmodoro, A., Prince, B., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 51–70. [Google Scholar]

- Gertz, S. Plotinus: Ennead II.9, Against the Gnostics; Parmenides: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Noble, C.I. Plotinus on Providence and Fate. In The New Cambridge Companion to Plotinus; Gerson, L.P., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2022; pp. 386–409. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, P. Adamson, P. A Note on Freedom in the Circle of al-Kindī. In Abbāsid Studies; Montgomery, J.E., Ed.; Peeters: Leuven, Belgium, 2004; pp. 199–207. [Google Scholar]

- Eliasson, E. The Notion of “That Which Depends on Us” in Plotinus and Its Background; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Coope, U. Freedom and Responsibility in Neoplatonist Thought; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. Early Philosophical Shiism: The Ismaili Neoplatonism of Abū Yaʿqūb Al-Sijistānī; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Sijistānī, Abū Yaʿqūb. Kashf Al-Maḥjūb; Corbin, H., Ed.; Institut Franco-Iranien: Tehran, Iran, 1979. [Google Scholar]

- Sejestânî, Abū Yaʿqūb. Le Dévoilement des Choses Cachées (Kashf Al-Mahjûb); Corbin, H., Ed.; Verdier: Paris, France, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Aminrazavi, M.; Nasr, S.H. (Eds.) Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Volume 2: Ismaili Thought in the Classical Age; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. The Wellsprings of Wisdom: A Study of Abū Yaʿqūb Al-Sijistānī’s Kitāb Al-Yanābīʿ; University of Utah Press: Salt Lake City, Utah, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijistānī. In Encyclopaedia of Islam Three (EI3); Fleet, K., Krämer, G., Matringe, D., Nawas, J., Rowson, E., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 2007; Available online: http://dx.doi.org.emedien.ub.uni-muenchen.de/10.1163/1573-3912_ei3_SIM_0060 (accessed on 10 March 2023).

- Landolt, H. Unveiling of the Hidden: Kashf Al-Maḥjūb. In Anthology of Philosophy in Persia, Volume 2: Ismaili Thought in the Classical Age; Aminrazavi, M., Nasr, S.H., Eds.; I.B. Tauris: London, UK, 2008; pp. 83–129. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. Abu Yaʿqūb Al-Sijistānī: Intellectual Missionary; I.B. Tauris and the Institute of Ismaili Studies: London, UK, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. Cosmic Hierarchies in Early Ismāʿīlī Thought: The View of Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijistānī. Muslim World 1976, 116, 14–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walker, P.E. Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijistānī in Modern Scholarship. Shii Stud. Rev. 2017, 1, 167–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stern, S.M. Arabico-Persica: III. Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijzī’s nickname: Panba-dāna, ‘cotton-seed’. In W. B. Henning Memorial Volume; Boyce, M., Gershevitch, I., Eds.; Lund Humphries: London, UK, 1970; pp. 409–416. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, S.M. Abu’l-Qāsim al-Bustī and his Refutation of Ismailism. J. R. Asiat. Soc. Great Br. Irel. 1961, 93, 14–35. [Google Scholar]

- Nafīsī, S. Tārīkh-e Naẓm-o Nathr dar Īrān-o dar Zabān-e Fārsī az Āġāz tā Pāyān-e Qarn-e Dahom-e Hejrī; Forūġī: Tehran, Iran, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, H. Introduction. In Abū Yaʿqūb Sijistānī: Kashf Al-Maḥjūb; Le Dévoilement des Choses Cachées, Traité Ismaélien du IVme Siècle de l’Hégire; Corbin, H., Ed.; Institut Franco-Iranien: Tehran, Iran, 1949. [Google Scholar]

- Khosrow, N. Zād Al-Musāfir, 2nd ed.; ʿEmādīḤāʾerī, S.M., Ed.; Mīrā-e Maktūb: Tehran, Iran, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Bīrūnī, A.R. Taḥqīq Mā Li-L-Hind Min Maqula Maqbula Fi L-ʿaql Aw Mardhula; ʿĀlam Al-Kutub: Beirut, Lebanon, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Landolt, H. Kashf Al-Maḥjub of Sejzi. In Encyclopædia Iranica; Yarshater, E., Ed.; Encyclopaedia Iranica Foundation: New York, NY, 1998; Volume XV/6, pp. 666–668. [Google Scholar]

- Khoyī, Z. ʿA. Abū Yaʿqūb Sejzī. In The Great Islamic Encyclopaedia, Musavi Bojnurdi, K., Ed.; Center for the Great Islamic Encyclopedia: Tehran, Iran, 1994; Volume VI, pp. 423–429. [Google Scholar]

- Ṣafā, D. Tārīkh-e Adabiyāt dar Īrān Az Āġāz-e ʿahd-e Eslāmī tā Dowreh-ye Saljūqī; 8 vols; Ferdows: Tehran, Iran, 1990; original printing 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Hirji, B. Abū Yaʿqūb Sijistānī: Al-Risāla al-bāhira fī l-maʿād. Taḥqīqāt-e Islāmī 1992, 7, 21–50. [Google Scholar]

- Bahār, M.-T. Sabk-Shenāsī, 2nd ed.; 3 vols; Parastū: Tehran, Iran, 1953. [Google Scholar]

- Ebrāhīmī Dīnānī, Ġ-Ḥ. Daftar-e ʿaql-o Āyat-e ʿeshq; Ṭarḥ-e Nou: Tehran, Iran, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Klein-Franke, F. The Non-Existent is a Thing. Le Muséon 1994, 107, 375–390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wisnovsky, R. Notes on Avicenna’s Concept of Thingness (shayʾiyya). Arab. Sci. Philos. 2000, 10, 181–221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Druart, T.-A. Shayʾ or res as Concomitant of Being in Avicenna. Doc. E Studi Sulla Tradiz. Filos. Mediev. 2001, 12, 125–142. [Google Scholar]

- Sijistānī, A.Y. Kitāb Ithbāt Al-Nubuwwāt; Madelung, W., Walker, P.E., Eds.; Ketāb-e Rāyzan: Tehran, Iran, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- van der Eijk, P. Galen on the Nature of Human Beings. In Philosophical Themes in Galen; Adamson, P., Hansberger, R., Wilberding, J., Eds.; BICS: London, UK, 2014; pp. 89–134. [Google Scholar]

- Galen. On Temperaments; Kühn, C.G., Ed.; Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1821. [Google Scholar]

- Galen. Galeni de Temperamentis; Helmreich, G., Ed.; Teubner: Leipzig, Germany, 1904. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, J.O. Always by Your Side—A Special Relationship: Ibn Abī Ashʿath on Humans and Horses. Viat. Mediev. Renaiss. Stud. 2021, 52/1, 17–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Connell, S. Hybrids in Aristotle’s Generation of Animals. In Aristotle’s Generation of Animals: A Comprehensive Approach; Follinger, S., Ed.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 181–208. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, B. Ethnobiological Classification. In Cognition and Categorization; Lloyd, B.B., Rosch, E., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, MI, USA, 1978; pp. 9–26. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, C.H. Folk Zoological Life-Forms. Their Universality and Growth. Am. Anthropol. 1979, 81, 791–817. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atran, S. Folk Biology and the Anthropology of Science. Cognitive Universals and Cultural Particulars. Behav. Brain Sci. 1998, 21, 547–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moazami, M. La Place de L’animal Dans La Conception Zoroastrienne. L’histoire des Animaux a Travers Les Textes Pehlevis; Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Section des Sciences Religieuses: Paris, France, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Schmidt, H.-P. Ancient Iranian Animal Classification. Stud. Indol. Iran. 1980, 5–6, 209–244. [Google Scholar]

- Eisenstein, H. Arabische Systematiken des Tierreichs. Z. Der Dtsch. Morgenländischen Ges. Suppl. 1988, 8, 184–190. [Google Scholar]

- Dörrie, H. Kontroversen um die Seelenwanderung im kaiserzeitlichen Platonismus. Hermes 1957, 85/4, 414–435. [Google Scholar]

- Walker, P.E. The Doctrine of Metempsychosis in Islam. In Islamic Studies Presented to Charles J. Adams; Hallaq, W.B., Little, D.P., Eds.; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1991; pp. 219–238. [Google Scholar]

- Madelung, W. Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijistānī and Metempsychosis. In Iranica Varia. Papers in Honor of Professor Ehsan Yarshater; Brill: Leiden, The Netherlands, 1990; pp. 131–143. [Google Scholar]

- Madelung, W. Abū Yaʿqūb al-Sijistānī and the Seven Faculties of the Intellect. In Mediaeval Ismaʿili History and Thought; Daftary, F., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1996; pp. 85–89. [Google Scholar]

- Aristotle. Generation of Animals, Platt, A. Trans. In The Complete Works of Aristotle; Barnes, J., Ed.; 6. print with Corrections; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1995; pp. 1111–1218. [Google Scholar]

- Hirji, B. A Study of Al-Risālah Al-Bāhirah. PhD Thesis, McGill University, Montreal, QC, Canada, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Rashed, M. Essentialisme: Alexandre d’Aphrodise Entre Logique, Physique et Cosmologie; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Virgi, S. Good, Bad, and Ugly Animals as Signs of the Creator in Medieval Islamic Encyclopaedias and Works of Natural Science. In Curiositas; Speer, A., Schneider, R.M., Eds.; De Gruyter: Berlin, Germany, 2022; pp. 395–415. [Google Scholar]

- [Pseudo-]Aristotle, Theologia. In Üsûlûcyâ: Aristoteles’in Teolojisi; Tüba: Ankara, Turkey, 2017.

- Badawī, ʿA. (Ed.) Aflūṭīn ʿinda l-ʿArab; Dirāsa Islāmiyya: Cairo, Egypt, 1947. [Google Scholar]

- Henry, P.; Schwyzer, H.-R. (Eds.) Plotini Opera: Vol II, Enneades IV-V, Plotiniana Arabica; Lewis, G., Translation; Desclée de Brouwer et Cie & L’Édition Universelle, S.A.: Paris, France; Bruxelles, Belgium, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Plotinus. The Enneads; Gerson, L.P., Ed.; Boys-Stones, G., Dillon, J.M., Gerson, L.P., King, R.A.H., Smith, A., Wilberding, J., Translation; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, P. Miskawayh on Animals. Rech. de Théologie et Philos. Médiévales 2022, 89, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Adamson, P. Abū Bakr al-Rāzī on Animals. Arch. für Gesch. der Philos. 2012, 94, 249–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ. Rasāʾil Ikhwān al-Ṣafāʾ; 4 vols; Al-Bustānī, B., Ed.; Maktab al-Aʿlām al-Islāmī: Qom, Iran, 1984; Rep. Beirut 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Monzavī, A. Fehrest-e Noskheh-hāye Khaṭṭī-ye Fārsī; 6 vols; Moʾasseseh-ye Farhangī-ye Manṭaqehʾī: Tehran, Iran, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Afshar, I. Ketābkhāneh-ye Saʿīd Nafīsī-yo noskheh-hāye khaṭṭī-ye ū. Dāneshkadeh-Ye Adabiyyāt-o ʿolūm-e Ensānī-ye Dāneshgāh-e Tehrān 1972, 78/1–2, 25–38. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adamson, P.; Amin Beidokhti, H. The Necessity and Goodness of Animals in Sijistānī’s Kashf Al-Maḥjūb. Philosophies 2024, 9, 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies9030072

Adamson P, Amin Beidokhti H. The Necessity and Goodness of Animals in Sijistānī’s Kashf Al-Maḥjūb. Philosophies. 2024; 9(3):72. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies9030072

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdamson, Peter, and Hanif Amin Beidokhti. 2024. "The Necessity and Goodness of Animals in Sijistānī’s Kashf Al-Maḥjūb" Philosophies 9, no. 3: 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies9030072

APA StyleAdamson, P., & Amin Beidokhti, H. (2024). The Necessity and Goodness of Animals in Sijistānī’s Kashf Al-Maḥjūb. Philosophies, 9(3), 72. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies9030072