Integral Studies and Integral Practices for Humanity and Nature

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Necessity of Integral Studies and Integral Practices

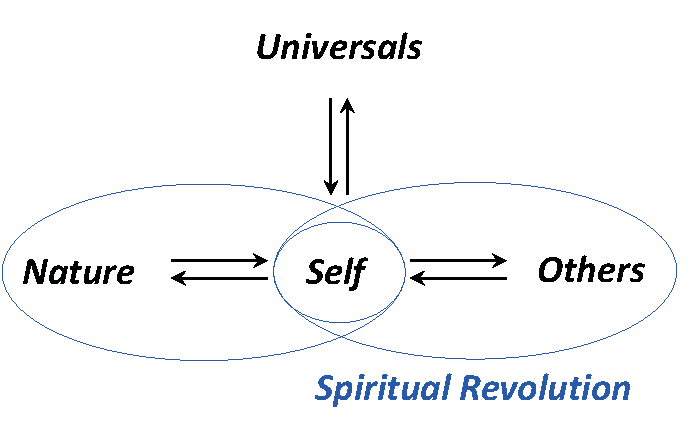

2.1. Limitations of the Spiritual Revolution and Modern Philosophy

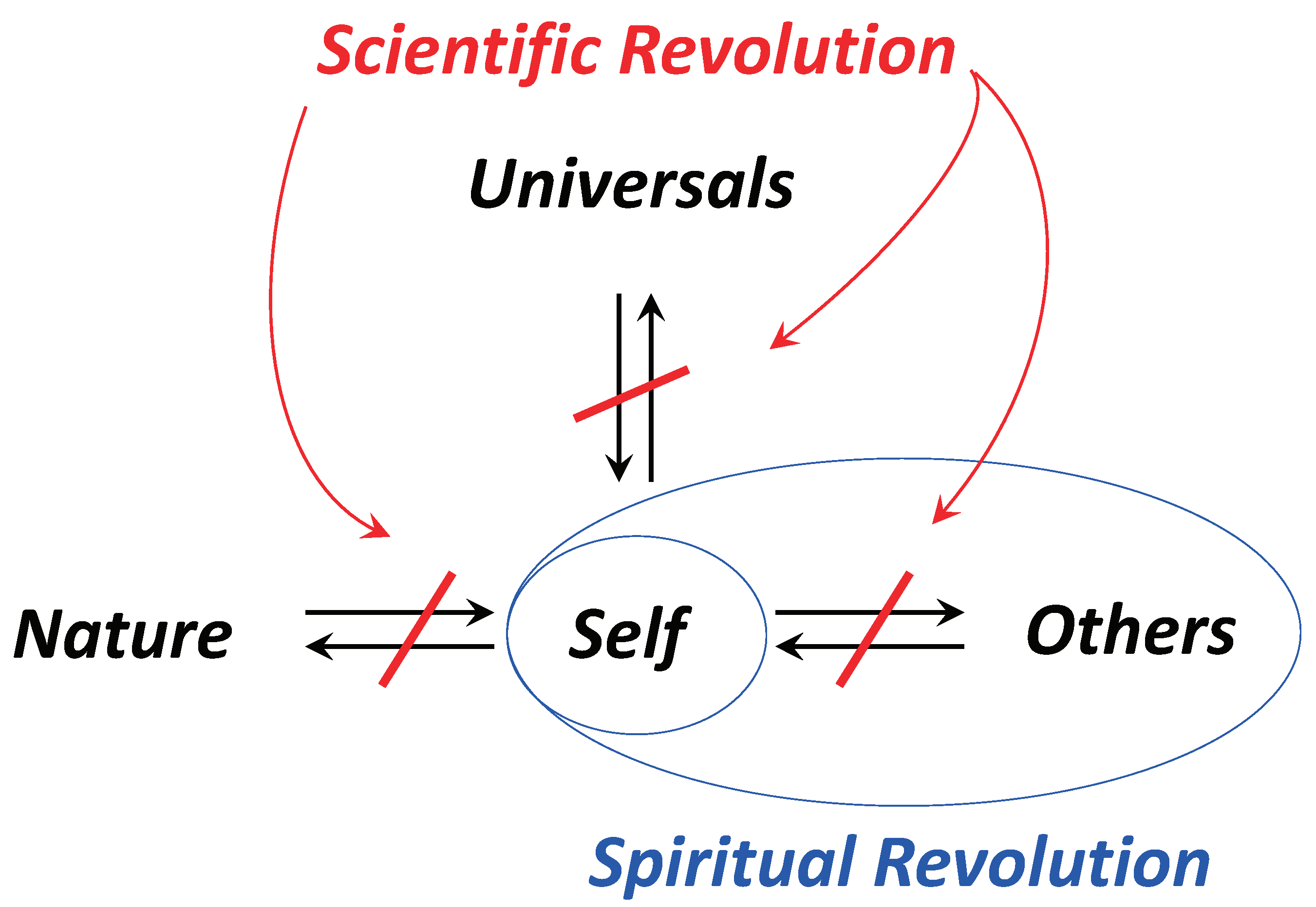

2.2. Limitations of the Scientific Revolution and Modern Science

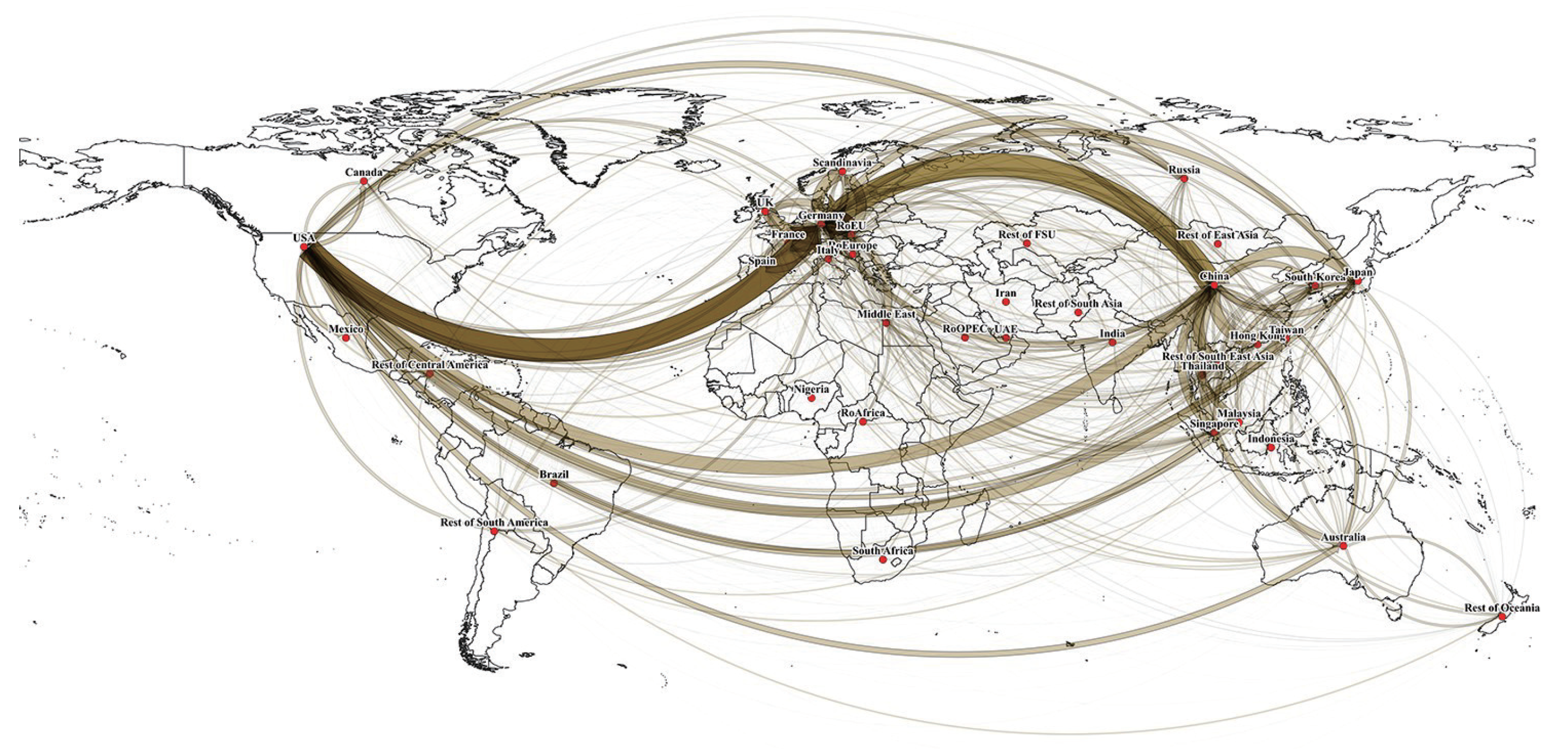

2.3. Contemporary Practical Problems That Threaten the Future of Humanity and Nature

2.4. Integral Studies and Integral Practices as a New Paradigm for the Environmental Revolution

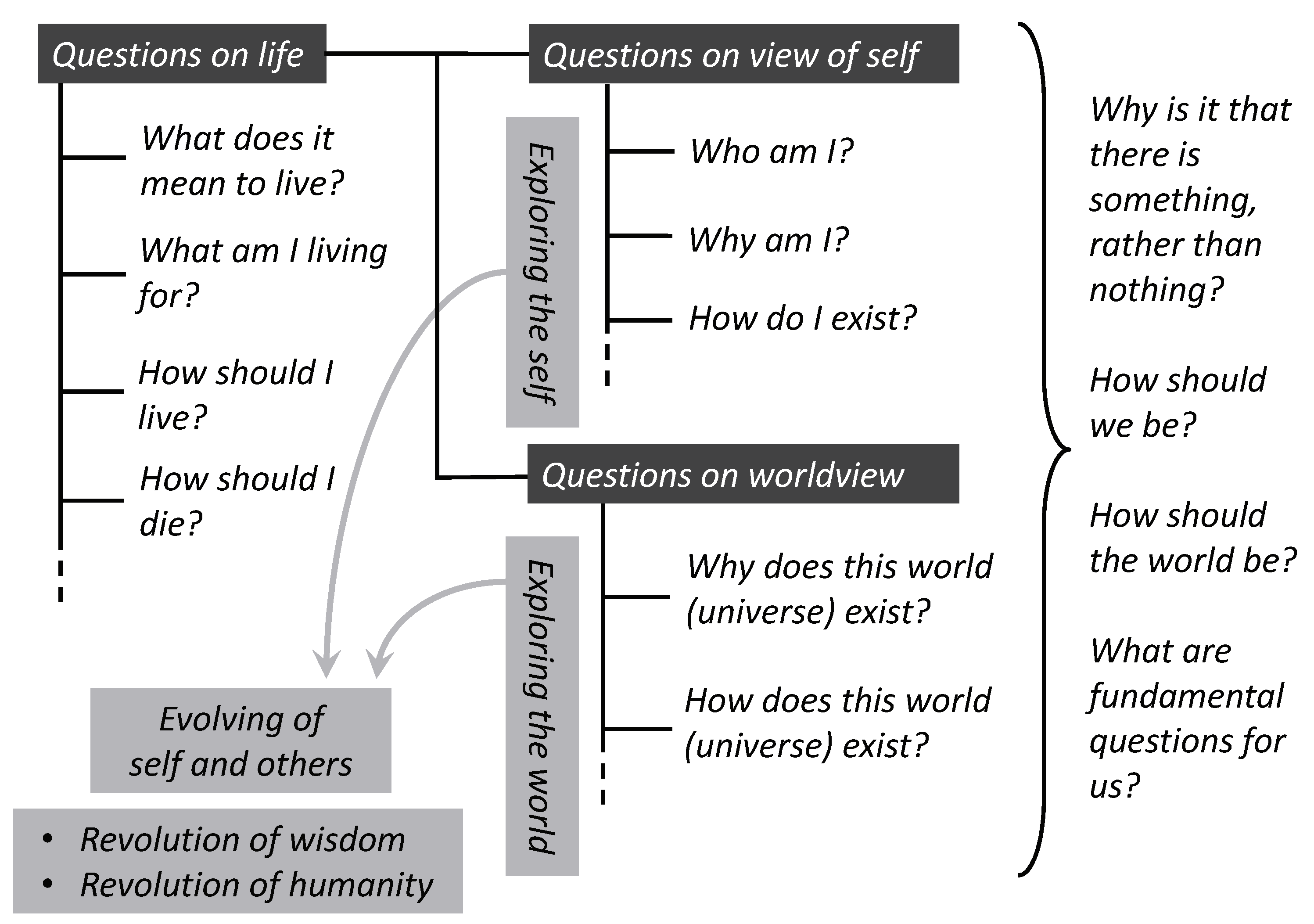

3. Purpose and Principle of Integral Studies and Integral Practices

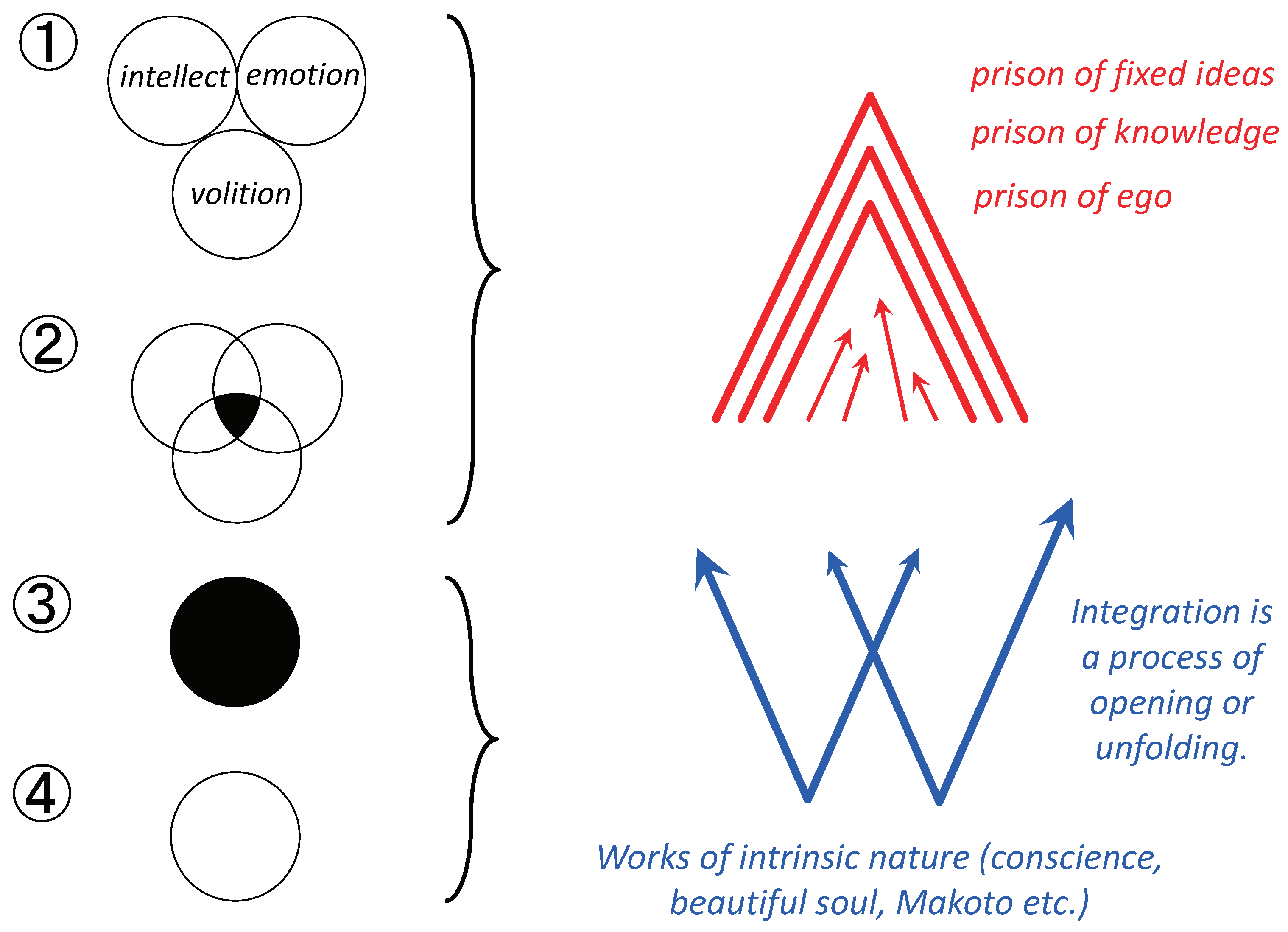

3.1. Purpose and Principle of Integral Studies and Integral Practices from the Viewpoint of the Nature of Human Beings

“Yours is idealism. It’s not accompanied by religious practice. Professor Anonymous, you sound like the Dengyō Daishi. You are obsessed. You cannot go any further that way. You’re given a chance by Buddha right now, so don’t think, just follow him.”

“You’re worn out. When you start dialoguing with yourself, put it in writing, express it, even in simple words. Be aware of whom you wish to communicate to. You are merely talking to something great. Don’t be engaged in inward-looking dialogue. You should also do something to communicate your thoughts in communicable words to others. Don’t let people read between the lines. For example, when you say thank you, no one will doubt it. Being grateful is good for the soul. You can’t find anyone as you are looking for someone with the same values. It’s your habit.”

“You are not equipped with the human capacity to carry out your great academic aspirations.”

“You can’t get confidence just by reading various books. Once you try Zen, you can gain confidence from there. You can make Zen one of your methodologies.”

“You will neglect your body if you continue to live like that. You don’t have the eyes of someone who can accomplish something. Don’t be so thick-headed, but engage yourself in practice.”

3.2. Purpose and Principle of Integral Studies and Integral Practices from the Viewpoint of the Nature of the Universe

4. Methodology of Integral Studies and Integral Practices

5. Further Scope of Integral Studies and Integral Practices

6. Concluding Remarks

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CO | carbon dioxide |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| DNA | Deoxyribonucleic acid |

| IAS | Invasive alien species |

| ICSU | International Council for Science |

| IPCC | Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change |

| NDE | Near-death experience |

| 1 | The ecosystem refers to a system formed by an ecological community and its environment that functions as a unit. |

| 2 | Biodiversity is the variation of life forms, plants, and animals within a given ecosystem, biome, or on the entire Earth. In other words, biodiversity is a measure of variation at the genetic, species, and ecosystem level. |

| 3 | My near-death experience was a NDE-like experience in a precise sense. The first reported case was the one that happened to Albert Heim, a Swiss geologist, in a climbing accident [55]. The full-scale research started in the 1960s (e.g., [56]). Characteristics of recent near-death experiences have been described in various ways (e.g., [57,58,59,60]). In earlier times, patients who had been resuscitated after cardiac arrest were the major subjects of the research, and the veracity of a near-death experience was judged with the Greyson scale [61]. In AWARE, the largest-ever project in this area, started by the University of Southampton in the UK in 2008, interviews with 330 patients who were resuscitated after cardiac arrest revealed that 140, or about 40% of them, reported that they were conscious while suffering cardiac arrest [62]. Given the variety of near-death experiences [61], recent research has included the self-reporting of NDE-like experiences without any critical conditions such as cardiac arrest [63], |

| 4 | The fundamental question means the origin of questions that cannot be investigated any further. |

| 5 | I take makoto in Japanese, following Ono (1962), to be a pure act, the work of a beautiful soul. |

References

- Ito, S. Turning Points of Civilization and the Role of Japan Today. In Problems of Advanced Economies; Miyawaki, N., Ed.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1984; pp. 89–99. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S. The Age of Transformation; Reitaku University Press: Kashiwa, Japan, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S. The Transformations of Civilization: Past and Future of the Humankind. J. Orient. Sci. 2016, 55, 114–131. [Google Scholar]

- Ito, S. “Spiritual Revolution” and “Scientific Revolution”. Stud. Moral. 2018, 81, 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T. Toward Creation of Integral Science: What is meaning of integration? Bull. Jpn. Soc. Glob. Syst. Ethics 2016, 11, 144–148. [Google Scholar]

- Edward, O.W. Consilience, the Unity of Knowledge; Alfred A. Knopf: New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Smuts, J.C. Holism and Evolution; Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 1926. [Google Scholar]

- Wilber, K. A Theory of Everything: An Integral Vision for Business, Politics, Science and Spirituality; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Laszlo, E. Science and the Akashic Field: An Integral Theory of Everything; Inner Traditions: Rochester, VT, USA; American Psychological Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- Goerner, S.J. Integral science: Rethinking civilization using the learning universe lens. Syst. Res. Behav. Sci. 2003, 20, 339–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ikeda, Y. From Complex System to Integrative Science. Diogenes 2010, 57, 117–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kayane, I. Environmental problems in modern china: Issues and outlook. In New Challenges and Perspectives of Modern Chinese Studies; Universal Academy Press Inc.: Tokyo, Japan, 2008; pp. 265–285. [Google Scholar]

- Kayane, I. Academic world comprehended by the philosophy of hydrological cycle. J. Jpn. Assoc. Hydrol. Sci. 2019, 49, 160–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Komatsu, H.; Rappleye, J.; Silova, I. Culture and the Independent Self: Obstacles to environmental sustainability? Anthropocene 2019, 26, 100198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, M. 1,500 scientists lift the lid on reproducibility. Nature 2016, 533, 452–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impett, J. Sound Work: Composition as Critical Technical Practice; Leuven University Press: Leuven, Belgium, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mauser, W.; Klepper, G.; Rice, M.; Schmalzbauer, B.S.; Hackmann, H.; Leemans, R.; Moore, H. Transdisciplinary global change research: The co-creation of knowledge for sustainability. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sustain. 2013, 5, 420–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Randers, J.; Goluke, U. An earth system model shows self-sustained thawing of permafrost even if all man-made GHG emissions stop in 2020. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 18456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forster, P.M.; Forster, H.I.; Evans, M.J.; Gidden, M.J.; Jones, C.D.; Keller, C.A.; Lamboll, R.D.; Quéré, C.L.; Rogelj, J.; Rosen, D.; et al. Current and future global climate impacts resulting from COVID-19. Nat. Clim. Chang. 2020, 10, 913–919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elhacham, E.; Ben-Uri, L.; Grozovski, J.; Bar-On, Y.M.; Milo, R. Global human-made mass exceeds all living biomass. Nature 2020, 588, 442–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Goka, K. Ecological approach for zoonosis-consideration of infectious disease risk from the view point of biological diversity. Med. Entomol. Zool. 2020, 71, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weston, P. We did it to ourselves’: Scientist says intrusion into nature led to pandemic. Guardian 2020, 25, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, C.K.; Hitchens, P.L.; Pandit, P.S.; Rushmore, J.; Evans, T.S.; Young, C.C.W.; Doyle, M.M. Global shifts in mammalian population trends reveal key predictors of virus spillover risk. Proc. R. Soc. Biol. Sci. 2020, 287, 20192736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, M.A. ‘Reality is an activity of the most august imagination’. When the world stops, it’s not a complete disaster—We can hear the birds sing! Educ. Philos. Theory 2022, 54, 217–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiménez Jiménez, L.I. Welcome to the End of the World! Ecum. Rev. 2021, 73, 509–523. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robin, M.M. La Fabrique des Pandémies: Préserver la Biodiversité, un Impératif Pour la Santé Planétaire; La Découverte: Paris, France, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Mazzocchi, F. Tackling modern-day crises: Why understanding multilevel interconnectivity is vital. BioEssays 2021, 43, 2000294. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostfeld, R.S.; Keesing, F. Biodiversity and Disease Risk: The Case of Lyme Disease. Conserv. Biol. 2000, 14, 722–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, S.; Jittapalapong, S.; Suputtamongkol, Y.; Abdullah, M.T.; Huan, T.B. Infectious Diseases and Their Outbreaks in Asia-Pacific: Biodiversity and Its Regulation Loss Matter. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e90032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suzán, G.; Marcé, E.; Giermakowski, J.T.; Mills, J.N.; Ceballos, G.; Ostfeld, R.S.; Armién, B.; Pascale, J.M.; Yates, T.L. Experimental Evidence for Reduced Rodent Diversity Causing Increased Hantavirus Prevalence. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e5461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keesing, F.; Belden, L.K.; Daszak, P.; Dobson, A.; Harvell, C.D.; Holt, R.D.; Hudson, P.; Jolles, A.; Jones, K.E.; Mitchell, C.E.; et al. Impacts of biodiversity on the emergence and transmission of infectious diseases. Nature 2010, 468, 647–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Civitello, D.J.; Cohen, J.; Fatima, H.; Halstead, N.T.; Liriano, J.; McMahon, T.A.; Ortega, C.N.; Sauer, E.L.; Sehgal, T.; Young, S.; et al. Biodiversity inhibits parasites: Broad evidence for the dilution effect. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2015, 112, 8667–8671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rohr, J.R.; Barrett, C.B.; Civitello, D.J.; Craft, M.E.; Delius, B.; DeLeo, G.A.; Hudson, P.J.; Jouanard, N.; Nguyen, K.H.; Ostfeld, R.S.; et al. Emerging human infectious diseases and the links to global food production. Nat. Sustain. 2019, 2, 445–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morand, S.; Lajaunie, C. Biodiversity and Health: Linking Life, Ecosystems and Societies; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- de Bengy Puyvallée, A.; Kittelsen, S. Security. In Pandemics, Publics, and Politics: Staging Responses to Public Health Crises; Bjørkdahl, K., Carlsen, B., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2019; pp. 59–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyerson, L.A.; Mooney, H.A. Invasive alien species in an era of globalization. Front. Ecol. Environ. 2007, 5, 199–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hulme, P.E. Trade, transport and trouble: Managing invasive species pathways in an era of globalization. J. Appl. Ecol. 2009, 46, 10–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ielmini, M.R.; Pullaiah, T. Invasive Alien Species: Observations and Issues from Around the World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lenzen, M.; Li, M.; Malik, A.; Pomponi, F.; Sun, Y.Y.; Wiedmann, T.; Faturay, F.; Fry, J.; Gallego, B.; Geschke, A.; et al. Global socio-economic losses and environmental gains from the Coronavirus pandemic. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0235654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morand, S.; Owers, K.A.; Waret-Szkuta, A.; McIntyre, K.M.; Baylis, M. Climate variability and outbreaks of infectious diseases in Europe. Sci. Rep. 2013, 3, 1774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavicchioli, R.; Ripple, W.J.; Timmis, K.N.; Azam, F.; Bakken, L.R.; Baylis, M.; Behrenfeld, M.J.; Boetius, A.; Boyd, P.W.; Classen, A.T.; et al. Scientists’ warning to humanity: Microorganisms and climate change. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2019, 17, 569–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitmee, S.; Haines, A.; Beyrer, C.; Boltz, F.; Capon, A.G.; de Souza Dias, B.F.; Ezeh, A.; Frumkin, H.; Gong, P.; Head, P.; et al. Safeguarding human health in the Anthropocene epoch: Report of The Rockefeller Foundation–Lancet Commission on planetary health. Lancet 2015, 386, 1973–2028. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernardeau-Moreau, D. Health Crisis and the Dual Reflexivity of Knowledge. Soc. Sci. 2022, 11, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saito, K. Marx in the Anthropocene: Value, Metabolic Rift, and the Non-Cartesian Dualism. Z. FüR Krit. Sozialtheorie Philos. 2017, 4, 276–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Žižek, S. Pandemic!: COVID-19 Shakes the World; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Žižek, S. Pandemic! 2: Chronicles of a Time Lost; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Rockströom, J.; Steffen, W.; Noone, K.; Persson, Å.; Chapin, F.S.; Lambin, E.F.; Lenton, T.M.; Scheffer, M.; Folke, C.; Schellnhuber, H.J.; et al. A safe operating space for humanity. Nature 2009, 461, 472–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Neill, D.W.; Fanning, A.L.; Lamb, W.F.; Steinberger, J.K. A good life for all within planetary boundaries. Nat. Sustain. 2018, 1, 88–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis. Contribution of Working Group I to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Impacts, Adaptation, and Vulnerability. Contribution of Working Group II to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- IPCC. Climate Change 2022: Mitigation of Climate Change. Contribution of Working Group III to the Sixth Assessment Report of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedlingstein, P.; Jones, M.W.; O’Sullivan, M.; Andrew, R.M.; Bakker, D.C.E.; Hauck, J.; Le Quéré, C.; Peters, G.P.; Peters, W.; Pongratz, J.; et al. Global Carbon Budget 2021. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2022, 14, 1917–2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pollard, K.S. What Makes Us Human? Sci. Am. 2009, 300, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harari, Y.N. Sapiens: A Brief History of Humankind by Yuval Noah Harari; Harper: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Heim, R. Incantamenta magica. Philolog. Jahrb. Suppl. 1892, 19, 512. [Google Scholar]

- Kübler-Ross, E. On Death and Dying: What the Dying Have to Teach Doctors, Nurses, Clergy and Their Own Families; Touchstone: New York, NY, USA, 1969. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, R.A. Life After Life: The Investigation of a Phenomena, Survival of Bodily Death; Mockingbird Books: Covington, GA, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Raymond, M. Life After Death; Bantam: New York, NY, USA, 1975. [Google Scholar]

- Moody, R.A.; Paul, P. The Light Beyond: New Explorations by the Author of Life after Life; Bantam Books: New York, NY, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- Ring, K.; Valarino, E.E. Lessons from the Light: What We Can Learn from the Near-Death Experience; Red Wheel/Weiser: Newburyport, MA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Greyson, B. The near-death experience scale. Construction, reliability, and validity. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1983, 171, 369–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parnia, S.; Spearpoint, K.; de Vos, G.; Fenwick, P.; Goldberg, D.; Yang, J.; Zhu, J.; Baker, K.; Killingback, H.; McLean, P.; et al. AWARE—AWAreness during REsuscitation—A prospective study. Resuscitation 2014, 85, 1799–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Charland-Verville, V.; Jourdan, J.P.; Thonnard, M.; Ledoux, D.; Donneau, A.F.; Quertemont, E.; Laureys, S. Near-death experiences in non-life-threatening events and coma of different etiologies. Front. Hum. Neurosci. 2014, 8, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T. Sustainability of “Great Chain of Being”. In On the Value of Nature and Life: Opening Up Eco-Philosophy and Sustainability Science; Nonburusha Publishing Company: Tokyo, Japan, 2015; pp. 333–400. [Google Scholar]

- Brown, L.; Halweil, B. China’s water shortage could shake world food security. World Watch 1998, 11, 10–21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Brown, L.R. Who Will Feed China?: Wake-Up Call for a Small Planet; W. W. Norton & Company, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, D.T. Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism; Open Court: Chicago, IL, USA, 1908. [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki, D.T. Manual of Zen Buddhism; Grove Press: New York, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Keiji, N.; Maraldo, J.C. The Standpoint of Zen. East. Buddh. 1984, 17, 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Shun’ei, T. Living Yogacara: An Introduction to Consciousness-Only Buddhism; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2009. [Google Scholar]

- Maruyama, S.; Kurokawa, K.; Ebisuzaki, T.; Sawaki, Y.; Suda, K.; Santosh, M. Nine requirements for the origin of Earth’s life: Not at the hydrothermal vent, but in a nuclear geyser system. Geosci. Front. 2019, 10, 1337–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ito, S. Nishida, Whitehead, Prigogine: Linkages among Their Thoughts on “Becoming”. J. Orient. Sci. 2015, 54, 227–247. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, K. The End of Everything: (Astrophysically Speaking); Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Krauss, L.M. A Universe from Nothing: Why There Is Something rather than Nothing; Simon and Schuster: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Strecher, V.J. Life on Purpose: How Living for What Matters Most Changes Everything; HarperCollins: New York, NY, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Hong, H.V.; Hong, E.H. Fear and Trembling/Repetition; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Katayama, Y.; Yukawa, H. Field Theory of Elementary Domains and Particles. I. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 1968, 41, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katayama, Y.; Umemura, I.; Yukawa, H. Field Theory of Elementary Domains and Particles. II. Prog. Theor. Phys. Suppl. 1968, 41, 22–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Wilber, K. Integral Spirituality: A Startling New Role for Religion in the Modern and Postmodern World; Shambhala: Boston, MA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T.; Li, J.; Tokunaga, T.; Onuki, M.; An, K.; Hoshiko, T.; Ikeda, I. Integral Approach to Environmental Leadership Education: An Exploration in the Heihe River Basin, Northwestern China. In Proceedings of the 8th International Symposium on Southeast Asian Water Environment, Phuket, Thailand, 24–26 October 2010; Volume 8, pp. 40–49. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T.; Li, J.; Kubota, J.; Konagaya, Y.; Watanabe, M. Perspectives on Sustainability Assessment: An Integral Approach to Historical Changes in Social Systems and Water Environment in the Ili River Basin of Central Eurasia, 1900–2008. World Futures 2012, 68, 595–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Li, J.; Onuki, M. Integral Leadership Education for Sustainable Development. J. Integral Theory Pract. 2012, 7, 72–86. [Google Scholar]

- Akiyama, T.; An, K.J.; Furumai, H.; Katayama, H. The Concept of Environmental Leader. In Environmental Leadership Capacity Building in Higher Education: Experience and Lessons from Asian Program for Incubation of Environmental Leaders; Mino, T., Hanaki, K., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 19–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Li, J. Environmental Leadership Education for Tackling Water Environmental Issues in Arid Regions. In Environmental Leadership Capacity Building in Higher Education: Experience and Lessons from Asian Program for Incubation of Environmental Leaders; Mino, T., Hanaki, K., Eds.; Springer: Tokyo, Japan, 2013; pp. 81–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Kharrazi, A.; Li, J.; Avtar, R. Agricultural water policy reforms in China: A representative look at Zhangye City, Gansu Province, China. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2017, 190, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akiyama, T.; Hirata, T.; Fujimoto, T.; Hatakeyama, S.; Yamazaki, R.; Nomura, T. The Natural-Mineral-Based Novel Nanomaterial IFMC Increases Intravascular Nitric Oxide without Its Intake: Implications for COVID-19 and beyond. Nanomaterials 2020, 10, 1699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hattori, E.; Nakamura, K.; Hiroi, Y.; Sonoda, A.; Akiyama, T.; Kawakatsu, H. A World of Sustainability: The Idea of Tokowaka. Bull. Jpn. Soc. Glob. Syst. Ethics 2017, 12, 83–106. [Google Scholar]

- Masuda, K.; Akiyama, T.; Uegaki, T.; Nakagawa, M. The Study of Kyosei Society and “Self”: A Necessary Transformation of the View of Human Beings. Kyosei Stud. 2018, 12, 80–84. [Google Scholar]

- San Carlos, R.O.; Teah, H.Y.; Akiyama, T.; Li, J. Designing Field Exercises with the Integral Approach for Sustainability Science: A Case Study of the Heihe River Basin, China. In Sustainability Science: Field Methods and Exercises; Esteban, M., Akiyama, T., Chen, C., Ikeda, I., Mino, T., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 23–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Akiyama, T. Integral Studies and Integral Practices for Humanity and Nature. Philosophies 2022, 7, 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7040082

Akiyama T. Integral Studies and Integral Practices for Humanity and Nature. Philosophies. 2022; 7(4):82. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7040082

Chicago/Turabian StyleAkiyama, Tomohiro. 2022. "Integral Studies and Integral Practices for Humanity and Nature" Philosophies 7, no. 4: 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7040082

APA StyleAkiyama, T. (2022). Integral Studies and Integral Practices for Humanity and Nature. Philosophies, 7(4), 82. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies7040082