2. Shedding Light on Grewendorf’s Mirror Image Data

For native speakers, who have not read about examples like (1a–b) in the literature, the first and only possible reading of (1a) that comes to mind is that the doctor showed himself to the patients (plural!) in the mirror, as in (1′).

- (1′)

Der Arzti zeigte den Patienten sichi im Spiegel.

the doctori showed the.dat patients himselfi in.the mirror

‘The doctor showed the patients himself in the mirror.’

Here, the anaphor sich, which is uninflected for case, number, and gender, is referring to the subject, as expected, given that reflexive pronouns typically are subject-oriented. The non-anaphoric object den Patienten is understood not as acc singular masculine but as dat plural. To eliminate the syncretism involved with these two forms and thereby force speakers to interpret the anaphor as getting its reference from the object (and also to present the verb and its arguments in their base order), we changed Grewendorf’s examples as shown in (2), where Patientin is singular feminine (f).

- (2)

a. dass der Arzti die Patientinj sich*i/j/ihr*j im Spiegel zeigte.

that the.nom doctori the.acc patient.fj refl*i/j/her*j.dat in.the mirror showed

‘that the male doctor showed the female patient herself in the mirror.’

b. dass

der Arzti der Patient

inj sichi/*j/sie?j im Spiegel zeigte.

2 that the.nom doctori the.dat patient.fj refli/*j/her?j.acc in.the mirror showed

‘that the male doctor showed {himself to the female patient/the female patientj her?j in

the mirror}.’

The non-anaphoric object, die Patientin in the (a)-example is now unambiguously acc-marked, which has the welcome consequence that speakers interpret the anaphor sich as being able to refer to only the object in the (a)-example and only the subject in the (b)-example. Still, speakers tend to want to rephrase (2a) entirely in order to express the intended meaning. This confirms that object orientation of the anaphor is a very marginal possibility that speakers generally avoid.

What adds to the marginality of Grewendorf’s data is the order of DO(

acc) > IO(

dat) because the unmarked order of objects in constructions involving a ditransitive verb is the opposite, IO(

dat) > DO(

acc), as in

jemandem etwas geben ‘give somebody.

dat something.

acc’. Also, taking a step back from the morpho-syntax of these sentences, it is worth noting that the situation of showing people themselves in the mirror is rather unusual. People are either shown something or someone other than themselves or, if they look into a mirror, no third party is involved. The one setting where this mirror image scenario might be considered normal is a hair salon: The hair stylist looks at and talks to the client in the mirror and shows them their hair, so that the mirror image, is treated like the actual person, the recipient, and the actual person whose hair is being shown, is treated like the mirror image, the theme—an interesting role reversal that we return to in

Section 4. First, in

Section 3, we examine double object binding data involving ditransitive verbs other than

zeigen ‘show’ and reconstruction effects to show that there is ample evidence for IO > DO, as opposed to DO > IO, as base order.

3. Evidence against DO > IO and for IO > DO as Base Order

Notice that constructions with classic ditransitive verbs like schicken ‘send’ and schenken ‘give as a gift’, as well as empfehlen ‘recommend’, which lends itself more naturally to object coreference involving animate entities, do not pattern like Grewendorf’s.

- (3)

a. *dass wir die Sängerini sichi als Wachsfigur schicken wollten.

that we the.acc singer.fem refl.dat as wax.figure send wanted

intended: ‘that we wanted to send the singer herself as a wax figure.’

b. *dass ich meinen Vateri zum Geburtstag sichi als Statue geschenkt habe.

that I my.acc father for.the birthday refl.dat as statue given have

intended: ‘that I gave my dad himself as a statue for this birthday.’

c. *dass man die Angeklagtei sichi als Anwältin empfohlen hat.

that one the.acc accused refl.dat as attorney recommended has

intended: ‘that people recommended to the accused herself as the attorney.’

In all of (3a–c), DO(acc) > IO(dat) is ungrammatical, and, importantly, all these examples get better if acc and dat case marking on the objects is switched, so that the order is IO(dat) > DO(acc), especially when sich is intensified with selbst ‘self’.

Furthermore, scope reconstruction effects strongly suggest that the base order of arguments in non-reflexive contexts is IO > DO, not DO > IO (see, e.g., [

13,

14]). Assuming that a quantifier can be interpreted either in its surface or its base position, we expect it to cause scope ambiguity if it moves from a position lower than another quantifier to a position higher than this other quantifier. Likewise, if the moving quantifier originates higher than the other quantifier, we do not expect scope ambiguity. These expectations are borne out in (4) and (5), respectively.

- (4)

Genau einen Gast hat sie jedem Freund vorgestellt (einen > jedem; jedem > einen)

exactly one.acc guest has she each.dat friend introduced

- (5)

Genau einem Freund hat sie jeden Gast vorgestellt (einem > jeden)

exactly one.dat friend has she each.acc guest introduced

Example (4) is ambiguous, the interpretations being that (i) there was one guest who was introduced to every friend or (ii) for every friend, there was a potentially different guest who was introduced to this friend. Example (5), on the other hand, is unambiguous, the only possible interpretation being that there was one friend to whom every guest was introduced. Thus, in (4), where the acc-marked quantificational DP has been topicalized, it takes scope over the dat-marked quantifier only in its landing site, not in its origin site, while, in (5), where the dat-marked quantificational DP has been topicalized, it takes scope over the lower acc-marked quantifier in both its origin and its landing site. This leads us to conclude that, in their base positions, the dat-marked IO must be structurally higher than, i.e., must c-command, the acc-marked DO, yielding IO > DO as base order.

Finally, a quantitative study by Featherston and Sternefeld, an acceptability rating experiment [

16], suggests that Grewendorf’s (1a)/our (2a) is only one of several possible double object formulations German speakers use to express ‘showing someone to themselves’ and that it is a rather exceptional one. The study produces three relevant generalizations about the Spell-Out possibilities for object coreference. They are given in (6a–c).

| (6) | a. | Dat antecedents are more accepted than acc antecedents. |

| | b. | Reflexives are more accepted than non-reflexive pronouns as anaphoric |

| | | elements. |

| | c. | Speakers prefer use of the intensifier selbst with both reflexive and non- |

| | | reflexive pronouns. |

Although these generalizations are just tendencies that may exist for a number of reasons not taken into account here, we would still like to point out that, if greater grammaticality is taken as an indication of underlying syntactic structures, generalization (a) suggests the following: Antecedents originate in (rather than move to) the inherent

dat-licensing position (contra [

1]), and, since

dat marks IOs, the antecedent should be the IO, and the anaphoric element, the DO. Generalizations (a) and (b) combined suggest that the DO is a reflexive rather than a non-reflexive pronoun, and since reflexives must be c-commanded by their antecedents, we arrive at the order of IO > DO (see [

3] for a different take on [

16]’s findings).

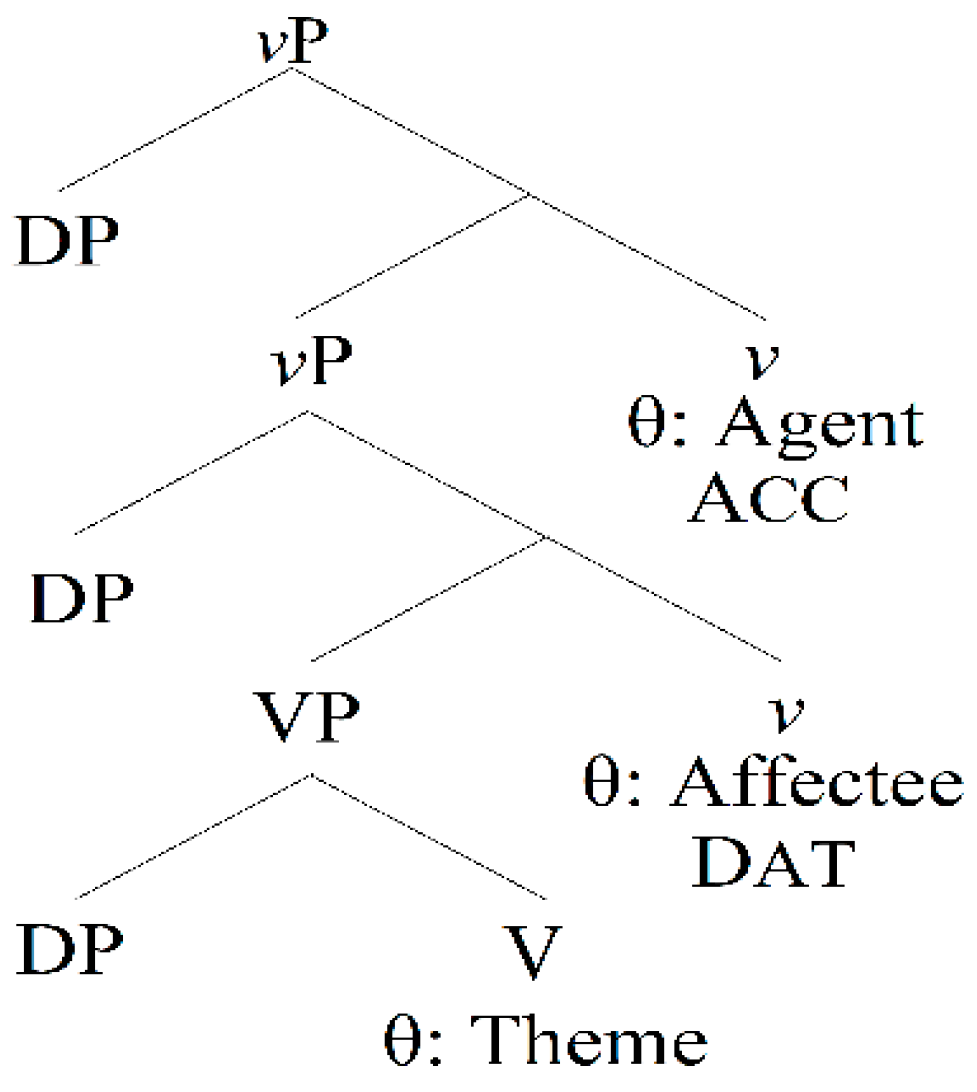

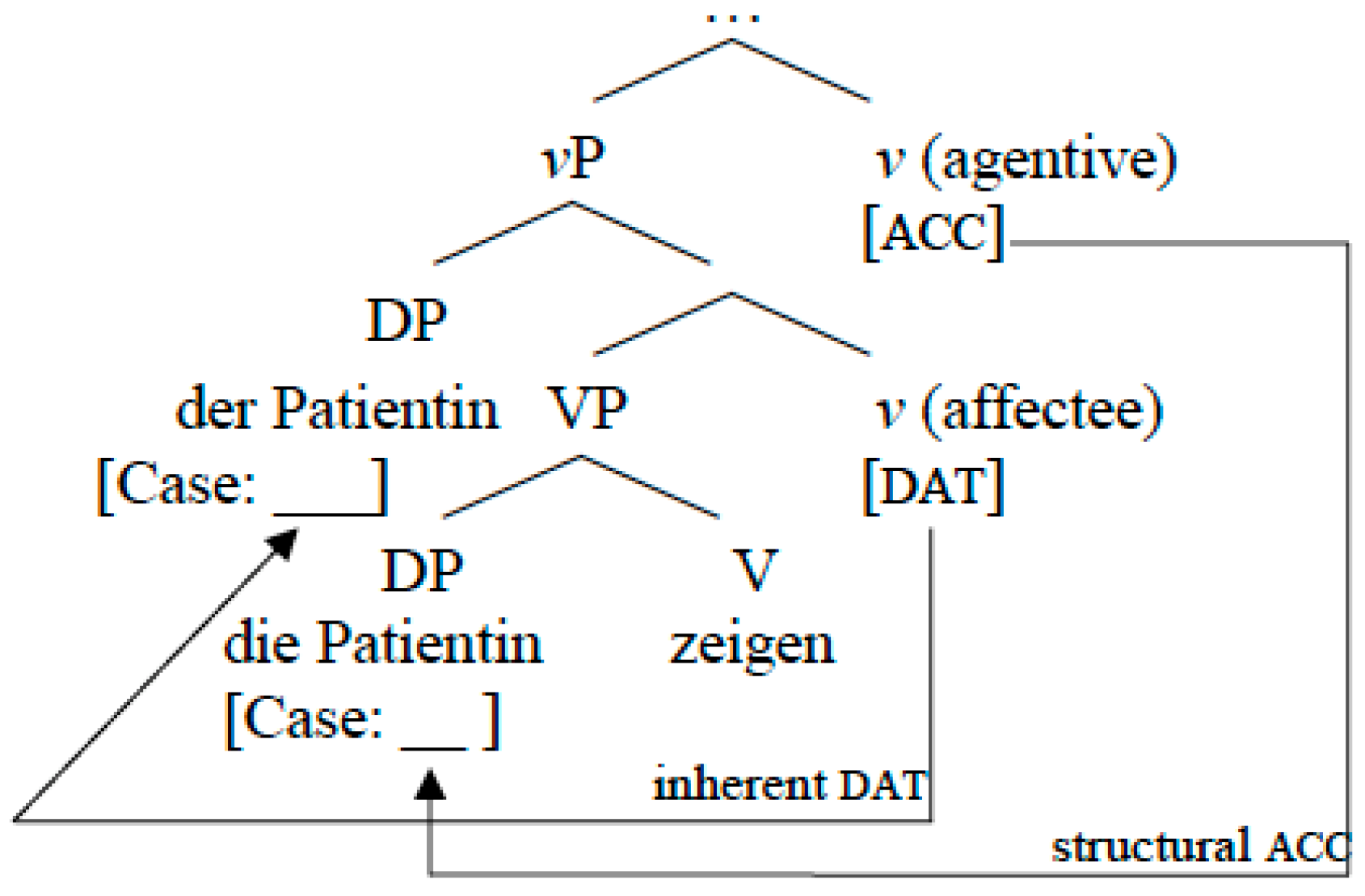

3 Consistent with our data in (3), the scope reconstruction effects in (4–5), and generalizations (6a–b), we argue for the structure in

Figure 1 as the base configuration of the verbal argument domain. This structure has also been independently motivated by [

17,

18,

19].

Figure 1.

Base structure of the verbal domain including Agent, Affectee

4 (IO), and Theme (DO).

Figure 1.

Base structure of the verbal domain including Agent, Affectee

4 (IO), and Theme (DO).

Each verbal head assigns its theta-role to the DP in its projection. Furthermore, the case feature listed under each of the

v-heads values the case of a certain DP as follows: Affectee

v licenses inherent

dat on the Goal/Recipient DP (IO), agentive

v licenses structural

acc on the Theme/Patient DP (DO), and T licenses structural

nom on the Agent DP (SUBJ).

4. The Exceptional Status of Object Coreference in (1a)/(2a): Interference from Inherent Reflexivity

The question is why the acc-marked antecedent is grammatical in Grewendorf’s (1a)/our (2a), with the verb zeigen ‘show’, but not in the other object coreference examples in (3), with the verbs schicken ‘send’, schenken ‘give (as a gift)’, and empfehlen ‘recommend’.

Notice that

zeigen can be used to express two different meanings: (i) ‘show someone something’, which corresponds to the ditransitive use of the verb,

jemandem etwas zeigen, and (ii) ‘let oneself be seen (by someone)/appear (in public)’, which corresponds to the inherently reflexive, idiomatic use of the verb,

sich (jemandem) zeigen, with an optional

dat argument. Meaning (ii) is shown in (7), where

sich can occur higher (in parentheses) or lower (not in parentheses).

| (7) | dass | (sich) | die | Königin | sich | der | Menge | zeigte. |

| | that | (refl) | the.nom | queen | refl.acc | the.dat | crowd | showed |

| | ‘that the queen appeared to the crowd.’ |

Meaning (ii) is the only readily available meaning expressed by Grewendorf’s (1b)/our (2b): the anaphor is ungrammatical when referring to the dat-marked object but grammatical when referring to the subject. The higher position of sich in (7) as an alternative to the lower one is also an option in (2b), repeated here as (2′b).

- (2′)

b. dass (sich) der Arzt der Patientin sich im Spiegel zeigte.

That (refl) the.nom doctor the.dat patient.f refl.acc in.the mirror showed

‘that the male doctor showed himself to the female patient in the mirror.’

This suggests that we are dealing with the inherently reflexive use of zeigen in these examples. Importantly, in its pre-subject position, sich cannot bear stress or be intensified with selbst, as shown in (2″b).

- (2″)

b. *dass sich selbst der Arzt der Patientin im Spiegel zeigte.

that refl self the.nom doctor the.dat patient.f in.the mirror showed

‘that the male doctor showed himself to the female patient in the mirror.’

Crucially, the verb zeigen in Grewendorf’s examples is most naturally interpreted as inherently reflexive, with a dat-marked non-reflexive object and subject-orientation of the anaphor sich, and this holds regardless of acc > dat or dat > acc order, that is, whether sich shows up higher or lower than the other object.

Based on everything laid out thus far, our hypothesis is as stated in (8).

| (8) | Hypothesis: The order of DO(acc) > IO(dat) in (1a)/(2a) is only acceptable because the preferred order of IO(dat) > DO(acc) in double-object constructions resembles the inherently reflexive use (meaning ii) of the verb in that the non-reflexive object is dat-marked, and when this meaning is not intended, DO(acc) > IO(dat) appears to be the best alternative, where the non-reflexive object is acc-marked. |

Interestingly, given the hair salon mirror image scenario (see

Section 2), this alternative even works semantically. The mirror image (normally the

acc-marked DO, i.e., what’s shown, the Theme) is treated like the actual person, and the actual person (normally the

dat-marked IO, i.e., the Recipient of the showing) is treated like the mirror image, so that the roles of Goal/Recipient and Patient/Theme are reversed, leading to

dat-acc case reversal as well. Vogel [

3] (p. 376) would argue against this because his claim is that, when antecedent and anaphor refer to different entities (like the actual person and the wax figure of this person), “only the real person may be the antecedent and the statue/image the bound element, not the other way around”. He calls this the “Ringo constraint”. To support his claim and equating wax figures with mirror images, he provides the examples in (9) (taken from [

20]) and (10).

| (9) | a. All of a sudden Ringo started undressing himself. |

| | (himself = person or statue) |

| | b. All of a sudden I accidentally bumped into the statues, and |

| | *Ringo toppled over and fell on himself. |

| | (Ringo = statue; himself = person) |

| | [20] (p. 4) |

| (10) | a. I showed John himself in the mirror. |

| | b.*I showed John to himself in the mirror. |

| | [3] (p. 376) |

(10b) is supposed to be a Ringo constraint violation because the antecedent (

John) is the mirror image, and the anaphor (

himself) is the real person. Contra Vogel, we argue that (10b) is perfectly fine given the hair salon scenario.

5 A mirror image is much more like the actual person than a wax figure and therefore escapes the Ringo constraint.

Ditransitive Verbs besides Zeigen6

If there are other exceptional ditransitive verbs like zeigen ‘show’, which allow object coreference with DO(acc) > IO(dat) order but without involving a mirror image situation, the hair-salon-induced thematic role and case reversal cannot be the whole story. This brings us back to our hypothesis in (8), i.e., interference from inherent reflexivity.

In this subsection, we walk the reader through examples with several other ditransitive verbs that allow for object coreference with DO(acc) > IO(dat) order. We conclude that what they all have in common is an inherently reflexive use and that this is what leads to the non-canonical order of DO(acc) > IO(dat).

The other ditransitive verb (besides

zeigen ‘show’) that shows up in Grewendorf’s examples [

4] which suggest that object coreference is only possible given DO(

acc) > IO(

dat) order is

vorstellen ‘introduce’. Its (di)transitive use, which we will label (i), (

jemandem.

dat) jemanden/etwas.

acc vorstellen ‘introduce someone/something (to somebody/one another)’, has the canonical IO > DO order as its unmarked order. It is really a transitive verb with an optional

dat argument. This is illustrated in (11).

- (11)

dass der Junge bei der Feier (seinen Eltern) seine Freundin vorstellte.

that the.nom boy at the party (his.dat parents) his.acc girl.friend introduced

‘that the boy introduced his girlfriend (to his parents) at the party.’

Its other uses are inherently reflexive: (ii) sich (jemandem/einander.dat) vorstellen ‘introduce oneself/say one’s name (to someone/one another)’, with an optional dat argument, as in (12):

- (12)

dass sich die Professorin (den Studierenden) vorstellt.

that refl the.nom professor-fem (the.dat students) introduces

‘that the professor is introducing herself (to the students).’

and (iii) sich etwas.acc vorstellen ‘imagine something’, as in (13):

- (13)

dass sich der Junge so etwas nicht vorstellen kann.

that refl the.nom boy such a.thing.acc not imagine can

‘that the boy cannot imagine something like that’

Notice the pre-subject position of

sich in both (12) and (13), supporting the analysis of uses (ii) and (iii) of the verb as being inherently reflexive. In (11), the order of the

dat and

acc-objects can, of course, be switched, but this does not speak against IO > DO as base order and is to be expected in a language where scrambling motivated by information structure is quite common (see, e.g., [

21,

22]).

However, Grewendorf’s examples in (14) [

4] and Vogel’s examples in (15) [

3], where only DO > IO is grammatical when a reciprocal or reflexive is involved, are problematic in that they seem to fall into the category of Grewendorf’s (1a)/our (2a).

- (14)

a. dass man die Gästei einanderi vorgestellt hat.

that one.nom the.acc guestsi one-another.dati introduced has

‘that the guests were introduced to each other.’

b. *dass man den Gästeni einanderi vorgestellt hat.

that one.nom the.dat guestsi one-another.acci introduced has

‘that the guests were introduced to each other.’

- (15)

a. Ich habe die Gästei sichi gegenseitig vorgestellt.

I have the.acc guestsi refl.dati each-other introduced

‘I introduced the guests to each other.’

b. *Ich habe den Gästeni sichi gegenseitig vorgestellt.

I have the.dat guestsi refl.acci each-other introduced

‘I introduced the guests to each other.’

Assuming that the reciprocal einander functions as an anaphor, Grewendorf treats it just like the reflexive sich and therefore takes examples (14a–b) to make the same point as his examples (1a–b)/our (2a–b), namely that only the order of DO(acc) > IO(dat) is possible when anaphoric binding is involved.

We side with Sternefeld and Featherston [

15], who show that

einander is in fact not an anaphoric argument but just an adjunct that can be added to the (di)transitive uses of

vorstellen (i) and (ii). In …

dass sichi die Gastgeberi mir einander vorstellten ‘that the hosts introduced one another to me’, for instance, the reflexive

sich, the

dat mir, and the reciprocal

einander all co-occur. Given the high position of

sich, we know that we are dealing with the inherently reflexive use of the verb. Besides the

acc sich, the

dat mir must then be the one optional argument this use of the verb allows, and

einander can only be an adjunct added to clarify that the hosts did not introduce themselves but one another (A introduced B to me, and B introduced A to me). This in turn means that examples (14a–b) do not provide evidence against IO(

dat) > DO(

acc) because they are not actually double-object constructions. (14b) is ungrammatical simply because

*…dass man den Gästen vorgestellt hat ‘…that one introduced to the guests’, where

vorstellen has a

dat argument but is missing its obligatory

acc argument, is ungrammatical as well.

Turning to Vogel’s examples (15a–b), however, which express the same meaning as (14a–b) but avoid use of einander, we are indeed faced with a use of vorstellen that works like that of zeigen in (1a–b)/our (2a–b), suggesting that DO(acc) > IO(dat) is the only grammatical order when one of the co-referent objects is the reflexive sich. Crucially, no mirror image scenario is involved here, so an appeal to the hair-salon-induced role reversal is not an option. We can still, however, fall back on our hypothesis in (8) and appeal to interference of inherent reflexivity. As corroborated by examples like (16), even when the reflexive is not used in its high position (here after man ‘one’) but following the other object, dat-marking on that other object invokes subject-orientation of the reflexive.

- (16)

dass man den Gästen nicht nur sich sondern auch sein Konzept

that one.nom the.dat guests not only refl but also one’s.acc concept

vorstellen musste.

introduce must

‘that one needed to introduce to the guests not only oneself but also one’s concept.’

In (16), where

sich is coordinated with a non-reflexive DP (

sein Konzept), the inherently reflexive use of the verb,

sich jemandem vorstellen ‘introduce oneself/say one’s name’, is combined with the non-idiomatic ditransitive use of the verb

jemandem etwas vorstellen ‘introduce something to somebody’ Given our hypothesis, in order to disambiguate between meanings (i) and (ii), i.e., to avoid meaning (ii) and thus subject-orientation of the reflexive in (15), the non-reflexive object needs to be

acc-marked.

7Another verb with both ditransitive and inherently reflexive uses that can be found in the literature on object coreference is überlassen. Use (i) of this verb, jemandem.dat jemanden/etwas.acc überlassen, comes with the meaning ‘leave someone/something (as a task) to somebody’, as in (17).

- (17)

dass niemand einem Fremden eine wichtige Aufgabe überlassen würde.

that nobody.nom a.dat stranger an.acc important task leave would

‘that nobody would leave an important task to a stranger.’

The order of DO > IO sounds equally good here, but, again, this alternative word order option can easily be derived via non-case-related scrambling.

Use (ii),

sich jemandem.

dat überlassen ‘surrender or abandon oneself to somebody’, is the inherently reflexive, idiomatic version of this verb and is illustrated in (18), where

sich can once again occur in pre-subject position.

| (18) | dass | sich | der | Gläubige | voll | dem | Herrn | überlässt. |

| | that | refl | the.nom | believer | fully | the.dat | Lord | surrenders |

| | ‘that a believer fully surrenders to the Lord.’ |

Use (iii), jemanden.acc sich.dat selbst überlassen ‘leave an animate entity to its own devices’ is interesting in that it also comes with idiomatic meaning but is ditransitive instead of inherently reflexive. Here, the reflexive is not subject- but object-oriented. An example is provided in (19). Both the object-orientation of sich and the intensification of sich with selbst ‘self’ make it impossible for the reflexive to occur in pre-subject position in sentences like this.

- (19)

dass der Vater die Kinderi einfach sichi selbst überlässt.

that the.nom father the.acc childreni simply refl.dat self leaves

‘that the father simply left the children to their own devices.’

The ditransitive idiomatic use of

überlassen, which requires the order of DO(

acc) > IO(

dat), may make this otherwise marked word order particularly common with this verb. In fact, Featherston and Sternefeld [

16], referencing [

23], give the example in (20). They note that it is better when

sich occurs with

selbst, but that it is not ungrammatical as is.

| (20) | Hans | überlässt | die | Schwesteri | sichi. |

| | Hans.nom | leaves | the.acc | sister | refl.dat |

| | ‘Hans leaves his sister to herself.’ |

| | [16] (p. 28) |

The (marginal) acceptability of this example seems to be due to a combination of the normal ditransitive use (i) and the idiomatic ditransitive use (iii) of

überlassen. If the first object were

dat instead of

acc-marked, the inherently reflexive use (ii) would be invoked, as it is in (21).

- (21)

dass mani dem lieben Gott nicht nur sichi sondern auch seine

that one.nom the.dat dear God not only refl but also one’s.acc

Familie überlassen sollte.

Family surrender should

‘that people should surrender to their dear God, not only themselves but also their families.’

Thus, again, DO > IO order and therefore acc-marking of the first object in examples like (20) might be a way to ensure expression of meaning (iii), associated with the ditransitive use, and thus avoidance of meaning (ii), associated with the inherently reflexive use.

Another verb that allows for both IO > DO and DO > IO order, similar in meaning to

überlassen, is

anvertrauen. Its use (i),

jemandem.

dat jemanden/etwas.

acc anvertrauen is ditransitive and comes with the meaning ‘entrust somebody with someone/something’, as in (22).

| (22) | dass | niemand | einem | Fremden | ein | Geheimnis | anvertrauen | sollte. |

| | that | nobody.nom | a.dat | stranger | a.acc | secret | entrust | should |

| | ‘that nobody should entrust a stranger with a secret.’ |

Once again, there is a use (ii) of this verb,

sich jemandem.

dat anvertrauen ‘confide in somebody’, that is inherently reflexive and idiomatic. As expected and shown in (23), the inherently reflexive use of the verb allows

sich to occur in pre-subject position.

| (23) | dass | sich | Teenager | selten | ihren | Eltern | anvertrauen. |

| | that | refl | teenagers.nom | rarely | their.dat | parent | confide |

| | ‘that teenagers rarely confide in their parents.’ |

As with

überlassen, if the ditransitive use (i) is intended and the second object is a reflexive,

acc-marking of the first object, as shown in (24), is the best way to push object-coreference and thereby ensure that the inherently reflexive use (ii) does not get in the way of the intended meaning.

| (24) | Man | sollte | Kinderi | nicht | sichi | selbst | anvertrauen. |

| | one.nom | should | children.acc | not | refl.dat | self | entrust |

| | ‘One should not entrust children with themselves.’ |

If the first object is

dat-marked, the inherent reflexive use (ii) of the verb and thus subject-orientation are unavoidable, even if the reflexive occurs in a normal internal argument position, as in (25). This example, like (16) and (21), combines the subject-oriented ditransitive meaning (i) with the inherently reflexive meaning (ii).

- (25)

dass die junge Fraui dem Therapeuten sichi und ihre gesamte

that the.nom young woman the.dat therapist refl and her.acc whole

Lebensgeschichte anvertraut hat.

life-story entrusted has

‘that the young woman confided in the therapist with herself and her whole life story.’

The last verb to be discussed here is

aussetzen, which is known for obligatory

acc>

dat order of the internal arguments in its ditransitive use (i),

jemanden/etwas.

acc einer Substanz/einem Zustand.

dat aussetzen ‘expose someone/something to a substance/state, as in (26).

| (26) | dass | man | niemanden | der | Kälte | aussetzen | sollte. |

| | that | one.nom | nobody.acc | the.dat | cold | expose | should |

| | ‘that one should not expose anybody to the cold.’ |

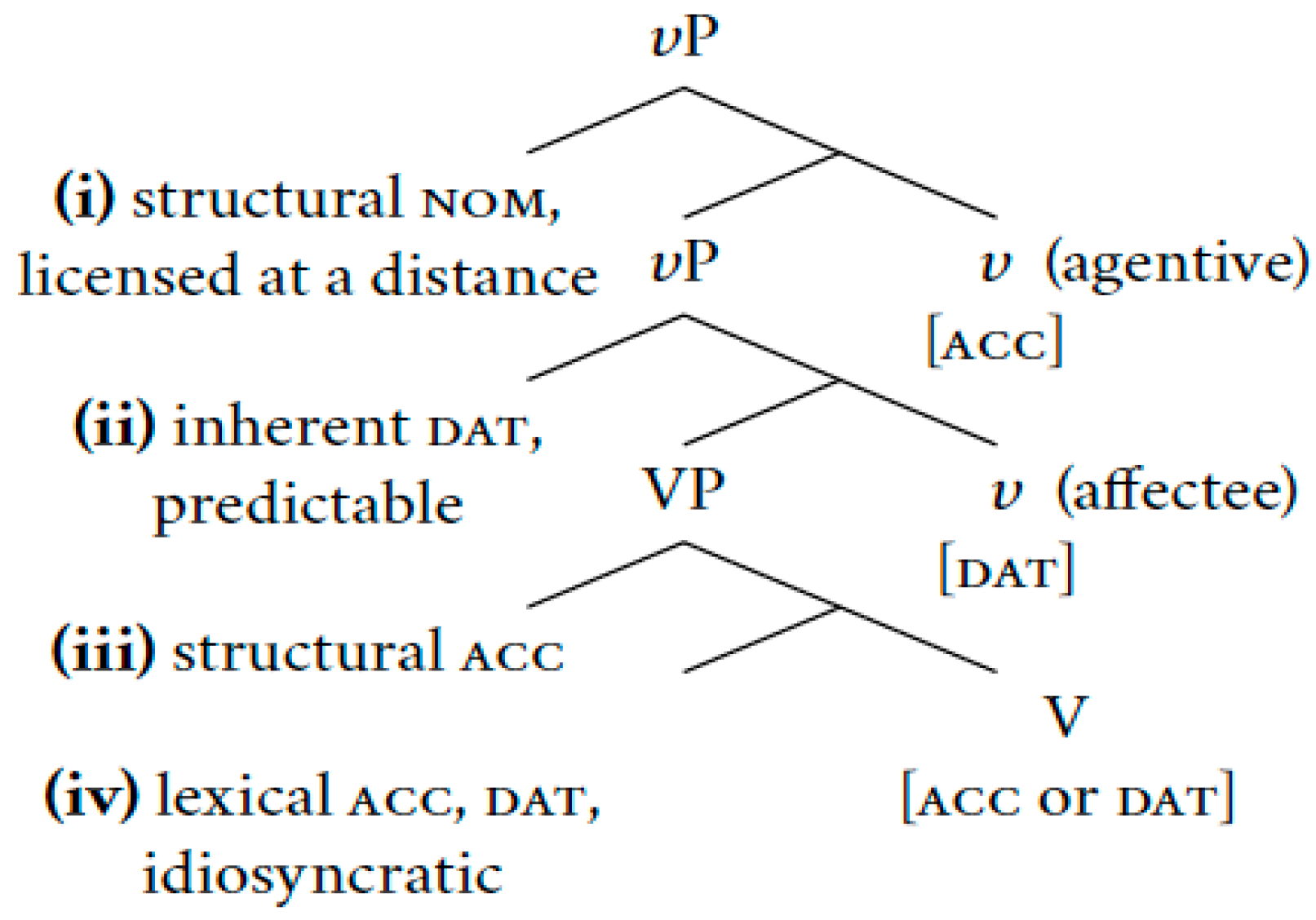

This might appear to be evidence against IO(

dat) > DO(

acc) as the base order of all double-object constructions, but, as laid out in [

19], it is not. Looking back at

Figure 1, repeated here as

Figure 2, with an added argument slot, it is easy to see how exceptionally patterning verbs like

aussetzen and

unterziehen ‘cause to undergo’ can be analyzed while maintaining IO(

dat) > DO(

acc) base order.

In (26), the first (

acc-marked) object is the structurally case-licensed DO in Spec VP (see position (iii) in

Figure 2). There is no IO because the second object is not an inherently case-marked

dat-argument, i.e., it is not an Affectee (animate Goal, Recipient, or Source), so position (ii) in

Figure 2 is not used—there is no affectee

vP layer. The second (

dat-marked) object is a lexically (idiosyncratically) case-marked nominal in sister-to-V position (see position (iv) in

Figure 2). Object-coreference with

aussetzen or

unterziehen is virtually impossible to construe.

Finally, use (ii) of aussetzen, ein.acc Lebewesen aussetzen ‘abandon/leave someone/an animal (on the street)’ is monotransitive and is thus incompatible with object coreference.

To conclude this section, all the potentially ditransitive verbs discussed here, which have also been used in the literature to argue for DO(

acc) > IO(

dat) as underlying order based on object coreference binding facts like those discovered by Grewendorf, have an inherently reflexive use. This supports our hypothesis in (8), namely that the order of DO(

acc) > IO(

dat) is only acceptable because the preferred order of IO(

dat) > DO(

acc) in double-object constructions resembles the inherently reflexive use of the verb, with a

dat-marked non-reflexive object, and when this meaning is not intended, the best alternative seems to be

dat-acc case switching, so that the non-reflexive object is

acc-marked. Unless the scenario described by the verb involves a hair salon role reversal, only the cases of the two objects are switched, not also their thematic roles.

Section 5 works through an attempt at a formal account of this.

5. Towards a Formal Account of Case-Switching in Object Coreference Constructions

According to Bruening’s theory of idiom formation [

18], the subject-oriented anaphors in the examples discussed throughout this paper are generated within the VP, [

VP sich

ACC verb]. This forces the interpretation of the verb as an inherently reflexive, idiomatic predicate. Thus, the structure [

VP sich

ACC zeigen], when morphologically realized as marked, forces the interpretation of

zeigen as ‘appear/show oneself in public’ rather than the ditransitive ‘show’. We claim that the observed realizations of object coreference, which come with the interpretation of

zeigen as ‘show’, exhibiting

acc >

dat order or the addition of

selbst, are repair strategies which are used to prevent the inherently reflexive, subject-oriented interpretation of

sich.

In the formal implementation of this, we must take interpretation and lexical meaning to result from the output of not only LF but also PF. It is the contents of (the extended) VP which are responsible for encoding meaning differences. Based on the case-marking of the anaphor and its antecedent or the inclusion of

selbst, the verb’s lexical meaning shifts. If interpretation is read off the structure and form of the expression, then this is perhaps as expected. The Encyclopedia in Distributed Morphology [

24] is a list of special/idiomatic meanings that can be associated with single lexical items (terminal nodes) or with larger structures [

25,

26]. This list is consulted after the output of PF and LF functions. Given the regularity of the lexical semantic force for inherently reflexive verbs, relegating their meaning to the Encyclopedia might seem concerning. However, all words and phrases in Distributed Morphology may involve Encyclopedic knowledge [

25,

26]. As roots themselves lack specific lexical semantic meaning, it is only in their morpho-syntactic context that they are evaluated.

In the case of German reflexive ditransitive constructions, inherently reflexive predicates have unique meaning based on the combination of V and the

acc-marked anaphor.

8 When not used ditransitively, verbs with [

VP sich

ACC V]-structure introduce both necessary components for interpretation within the same domain, VP. This does not prevent further movement of the anaphor, as is evident from the high position of

sich in many of the examples in

Section 4. We assume that, despite movement, the anaphor can still be interpreted locally to the verb. This may be via reconstruction based on any structure or features remaining after linearization. Encyclopedic interpretation, then, can be based on both syntactic structure and surface morphology.

If the Encyclopedia interprets [VP sichACC zeigen] or [antecedentDAT [VP sich zeigen]], it yields the inherently reflexive, idiomatic meaning. If the intended conceptual force of the sentence is non-inherently reflexive, a crash results and the sentence will not be interpreted.

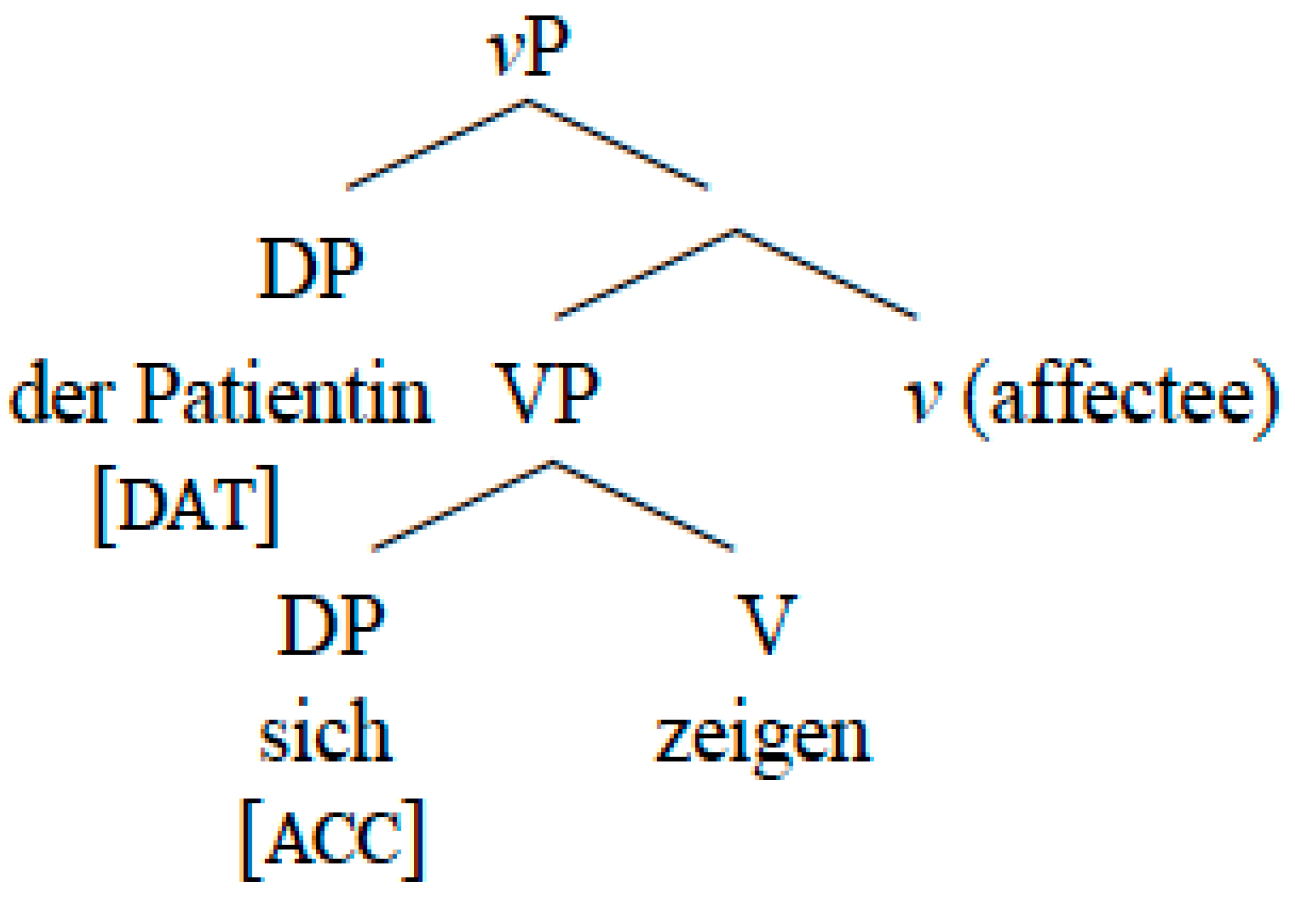

Consider the structure we propose for object co-reference in double-object constructions (DOCs) like ‘show the patient herself’ in

Figure 3.

If this structure is reconstructed and fed into the Encyclopedia, it yields an interpretation consistent with the inherently reflexive meaning because the anaphor is interpreted to have acc case. In order to prevent a mismatch between idiomatically assigned meaning and the conceptual force of the sentence, another form of the sentence must be selected for interpretation.

What other structures are available for interpretation? If we broaden the scope of evaluation for these options to include Encyclopedic interpretations, we can derive the variety of options available for binding in German DOCs. Within the narrow syntax, German object coreference is built as in

Figure 3, where the anaphor is c-commanded by the R-expressions with which it can be intended to be coreferential. In this configuration, we are able to uphold the standard assumptions about binding theory [

5]. While the exact series of operations which licenses (or builds) the anaphor may not be the same as on this early approach (see below for some discussion), we are nonetheless able to maintain the same configuration of binding. Building on other c-command diagnostics for argument structure, like scope discussed in

Section 3, we can presume this is the stable structure for introducing arguments in German.

If the structure in

Figure 3 is correct and the mapping of arguments and case features is always the most direct, then we predict that [

VP sich

ACC zeigen] and its inherently reflexive interpretation is the sole realization of such a structure. However, there are a variety of different realizations of reflexive DOCs. More specifically, there are three: (a) a sentence strictly faithful to the narrow syntactic representation, (b) a sentence with an element interrupting the idiomatic VP, and (c) a sentence marked morphologically to prevent reconstruction of the idiomatic VP.

Option (a) is the inherently reflexive (idiomatic) realization: [VP sichACC zeigen] is generated and sent to the Encyclopedia for interpretation. Given that the inherent reflexive meaning is the one intended by the speaker, the sentence is interpreted and produced. If the inherent reflexive meaning is not meant by the speaker, the interpretation of the structure will clash with the intended force, producing a crash.

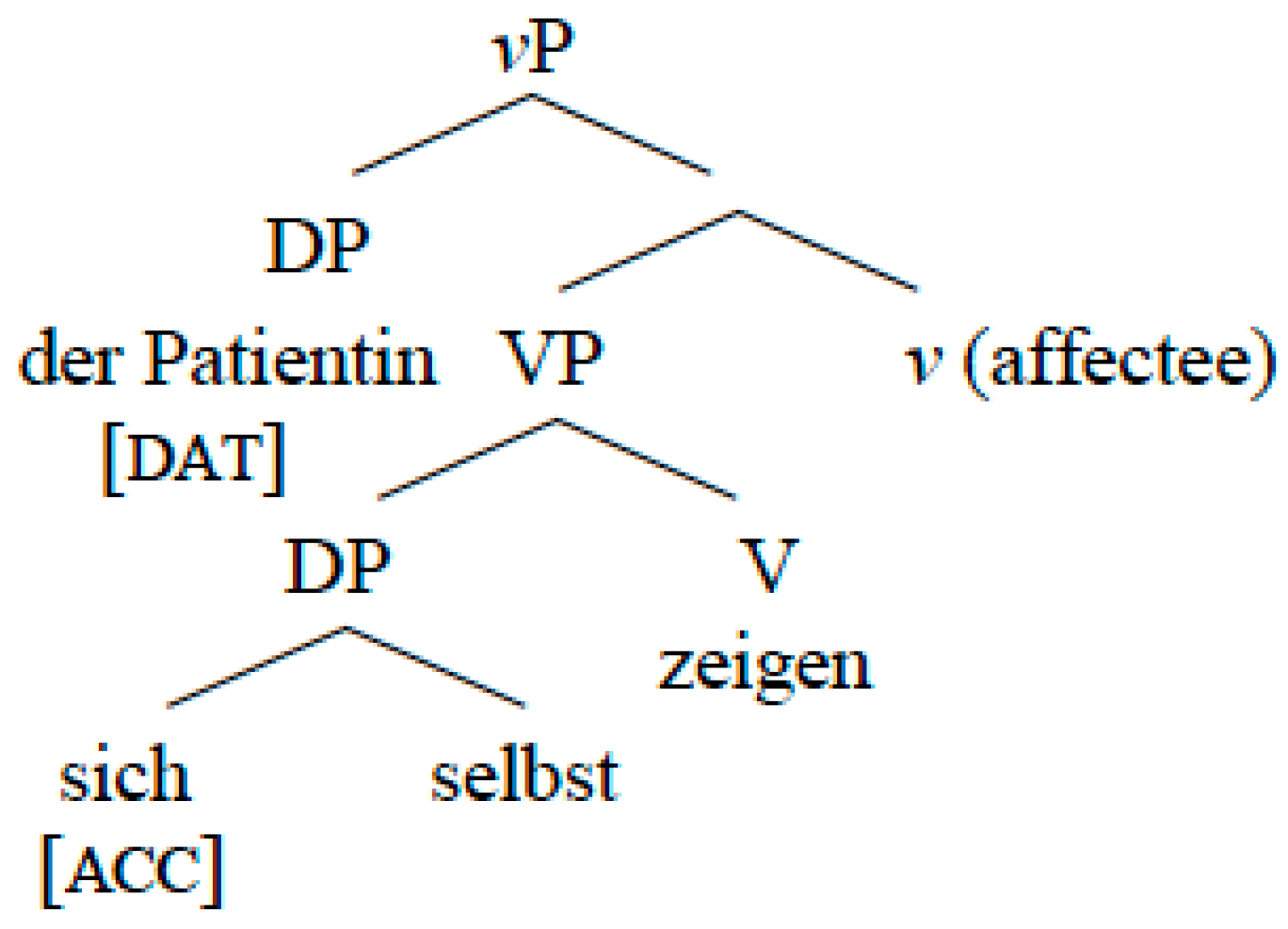

Option (b) is to interrupt the idiomatic VP: [VP sichACC selbst zeigen] is derived by the insertion of the intensifier selbst after the anaphoric element.

The use of

selbst can be due to selection from the numeration and inclusion in the derivation proper, but because

selbst is always an optional addition to the anaphor, when non-inherently reflexive,

selbst-insertion may be a last resort operation to disambiguate the orientation of the anaphor. This may be tied to late insertion of adjuncts [

27]. Featherston and Sternefeld’s quantitative generalization (c) from

Section 3 states that coreference is most readily acceptable if the anaphor is intensified with

selbst [

16]. This may be the most minimal alteration to the base structure that prevents a crash at the Encyclopedia. This candidate does not produce inherently reflexive meaning because the Encyclopedic interpretation must be local. As noted in

Section 4, inherently reflexive anaphors cannot be intensified by

selbst (see also [

28]). The

selbst-structure, shown in

Figure 4, interrupts the idiomatic domain in

Figure 3, thus allowing for the non-inherently reflexive, ditransitive interpretation.

Note that, since the non-idiomatic/non-inherently reflexive ditransitive reading with subject-orientation of

sich is still available in

Figure 4, at least marginally,

selbst-insertion facilitates, but does not strictly force, the desired object-coreference reading.

Option (c) involves case switching to yield [antecedentACC [VP sichDAT zeigen]]. Unlike selbst-insertion, this repair strategy completely prevents subject orientation of sich, guaranteeing object coreference. Consider again (2a), our version of Grewendorf’s (1a), reproduced here as (27).

- (27)

dass der Arzti die Patientinj sich*i/j/ihr*j im Spiegel zeigte.

that the.nom doctori the.acc patient.fj refl*i/j/her*j.dat in.the mirror showed

‘that the male doctor showed the female patient herself in the mirror.’

The indirect object (IO)-antecedent is spelled out with morphological acc, despite the IO’s inherent dat case assigned in the narrow syntax.

The exact mechanism for the transfer of case features is unclear, but an obvious solution to pursue is the adoption of a derivational approach to binding, that is, one on which anaphors are licensed by movement or agreement. Such an approach would allow the sharing of features along the movement or agreement chain. Movement-based approaches to anaphora (e.g., [

9,

10]), license or rather produce anaphors by moving a DP to a position within the same domain that c-commands its original position. Subsequently, a Spell-Out rule must be stipulated that alters the realization of a bound DP from its full R-expression to an anaphor.

Johni likes Johni would become

John likes John himself based on a rule associated with chain reduction [

29]. Agreement approaches to anaphora (see, e.g., [

11]) require a phi-agreement process to license an uninterpretable anaphor. The anaphor and the antecedent enter an Agree relationship by which the phi-features are shared among the two DPs [

30]. Combining both movement and agreement, Rooryck and Vanden Wyngaerd argue that the anaphor is either generated c-commanding its antecedent inside the same nominal phrase or moved to the edge of the

vP-phase to c-command it. In need of phi-feature valuation, the anaphor probes its antecedent and enters into an Agree relation with it [

12]. In all of these approaches, a syntactic relationship is formed between anaphor and antecedent. We hypothesize that it is through this relationship that the case features of anaphor and antecedent might be switched. Particularly, movement-based binding accounts might provide the Spell-Out mechanisms that allow switching of the morphological features of the two DPs or, more specifically, alternating which DP undergoes reduction to an anaphor. Thus,

zeigte der Patientin die Patientin would be spelled out as

zeigte der Patientin die Patientin sich. This option is clearly the least minimal way of spelling out a structure, certainly compared to

selbst-insertion. Hence, it is not surprising how difficult it is to find corroborating data and thus to replicate Grewendorf’s findings.

A problem with our tentatively proposed derivational account of case switching is finding a trigger for an operation which functions rather unpredictably.

dat-acc case switching must be restricted to the very specific double-object coreference scenario being investigated here. As already explained, perhaps in an effort to prevent a crash at the Encyclopedic interface, the case switching operation applies to disambiguate the structure from its inherent reflexive meaning. The faithfully generated morphological string is produced and tested for its meaning, and, if it matches the speakers’ intention, is produced. If not, a substitution of the case features applies and meaning is again tested against the speaker’s intention. This substitution and testing against levels of meaning may be formulated as a phrasal application of Safir’s morphological competition for anaphora [

31].

Besides the rather heavy burden this analysis places on the Syntax-Encyclopedia interface, an even bigger worry is that the structure in

Figure 3, when fleshed out in a derivational approach to binding [

9,

10,

11,

12] is not the right base configuration for subject orientation of the anaphor. In order for subject orientation of the anaphor to interfere with an intended object-coreference scenario, the speaker would need the flexibility of having the anaphor refer to either the IO or the subject. Given the German reflexive pronoun

sich, which is underspecified for case, number, and gender and known for its ability to find a binder locally or across a phase boundary [

32,

33], this flexibility seems to be built in. However, on a movement-based derivational approach to binding, antecedent and anaphor start out as one and the same DP or at least enter into an Agree relation inside the same phrase, i.e., are necessarily coreferential. On Hornstein’s approach [

9], movement of the DP that antecedent and anaphor originate as creates an in situ copy and a moved copy. The latter ends up as the antecedent, and the former as the reflexive pronoun. This will be explained in more detail with the help of

Figure 5 below. In

Figure 3, if the speaker intends object coreference, the anaphor would have to be the result of the in situ copy of ‘the patient’ being replaced by the reflexive pronoun

sich. However, it would have to be the result of replacing an in situ copy of ‘the doctor’ if the speaker’s intention is the more common subject-object coreference. There should never be interference of the latter coreference possibility with the former because, depending on the intended meaning, either only the object DP or only the subject DP will be split into antecedent and anaphor via movement.

Figure 5 shows the object coreference scenario with unswitched

dat-acc case marking of IO and DO, given a derivational analysis à la Hornstein [

9]. Assuming that movement produces binding configurations, Hornstein argues for English that a DP like ‘the patient’ merges with

self before moving to a higher structural position. The case of each element, the moved DP and

self, is determined by which element receives case first. In English,

self is assigned

acc in situ, allowing the DP to move and receive case higher in the structure. As discussed for German, anaphoric DPs do not always merge with

selbst ‘self’—

selbst is an optional intensifier [

34]. Therefore, both the moved DP and the copy left in situ have case features that need to be valued. Note that this means we have to assume that the two DP copies do not behave like the same object when it comes to being case-licensed. In

Figure 5, before case-licensing happens, the DP ‘the patient’ is merged with the verb, and then a copy of it moves and is remerged higher, combining via second merge with affectee (applicative)

v.

In order to prevent a moved DP from spelling out twice and creating a

*John likes John (self) configuration, Hornstein assumes, following Nunes [

35], that lower copies are deleted at PF in order to satisfy the conditions of Kayne’s Linear Correspondence Axiom [

36]. In English, this strands the

self-morpheme, which triggers the insertion of a pronoun to host the bound morpheme. In German, we might assume that NP/DP levels are deleted but strand certain features, like the case feature. This then requires insertion of the reflexive pronoun

sich.

To get the desired

acc-dat order of case-marked internal arguments, we can appeal to the possibility of the higher

dat-marked copy of the two DPs being deleted and replaced by

sich, producing an instance of backward control. This would need to be followed by movement of the lower

acc-marked DP above the

dat-marked

sich. This instance of backward control coupled with obligatory movement of the lower object above the higher object, as shown in

Figure 6, has to be motivated, of course.

Given the analysis argued for in

Section 4, the motivation for these operations should be interference of the inherently reflexive interpretation of the verb and thus subject orientation of the anaphor. But this brings us back to the problem of trying to fit our German object coreference facts into a derivational account of binding. Subject orientation of the anaphor cannot interfere with object coreference if it is a DP ending up in an object position from which the anaphor is derived and with which it is therefore automatically co-referent.