Self-Fulfilling Prophecies

Abstract

Joakim stands in front of his wardrobe, indecisively. In a flash of inspiration, he selects the black kimono. After all, he ponders, he already knows that’s what he’ll wear: the Delphic Oracle texted him as much that morning. Saved the mental labour of choosing an outfit, his mind wanders: ‘she knew, because I’m wearing it; but I’m wearing it, because she knew that I would…’

1. Causal Loops

In a causal loop, the arrows of causation go around in a circle, but there might be additional arrows that lead into the circle, or arrows that lead out of it. If there are no such branches then the loop is said to be causally isolated[2] (p. 259).

Closed causal chains in which some of the causal links are normal in direction and others are reversed… Each event on the loop has a causal explanation, being caused by events elsewhere on the loop. That is not to say that the loop as a whole is caused or explicable. It may not be[1] (pp. 148–149).

Strange! But not impossible, and not too different from inexplicabilities we are already inured to[1] (p. 149).

The other cases involve models of the general theory of relativity—first discussed by Kurt Gödel (1949)—that possess closed timelike curves in which time itself loops along a particular wordline. In such models, there is no backwards causation and travelling back in time requires no particular effort; one just has to follow an appropriately chosen worldline[2] (p. 259).

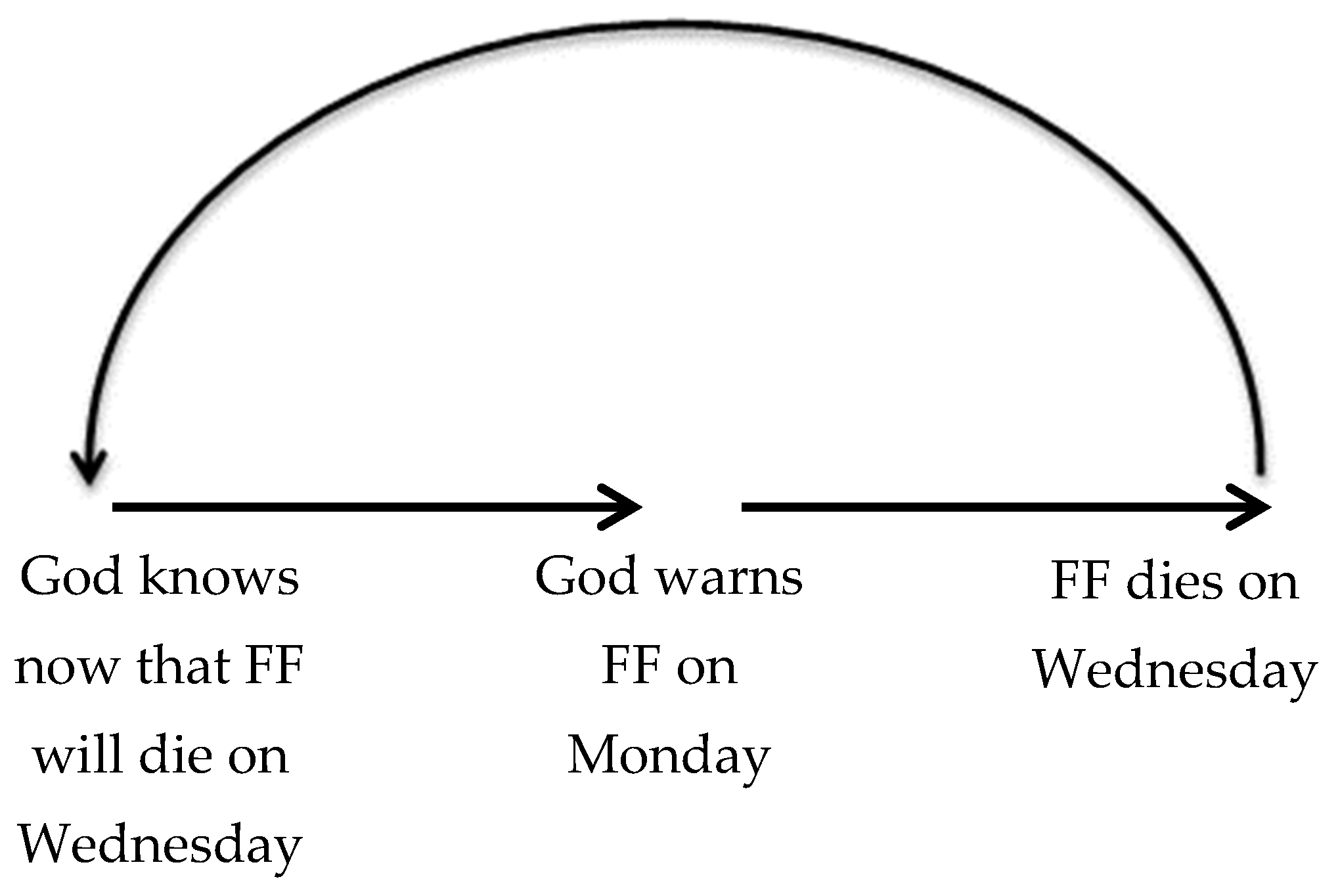

[Loops] can be constructed by granting the existence of some causal agent existing in eternity, something or someone that has equal and simultaneous access to events at several times. In such cases, either the causal efficacy of the later event could “run through” the causal efficacy of the eternal being to the earlier event, or the causal efficacy of the eternal being could “run through” the causal efficacy of the later event and back through eternity to the earlier event[15].

2. Self-Fulfilling Prophecies (SFPs)

The Oracle: […] And don’t worry about the vase.Neo: What vase?[Neo knocks a vase to the floor]The Oracle: That vase.Neo: I’m sorry.The Oracle: I said don’t worry about it. I’ll get one of my kids to fix it.Neo: How did you know?The Oracle: What’s really going to bake your noodle later on is, would you still have broken it if I hadn’t said anything[21].

While browsing through the library one day, I noticed an old dusty tome, quite large, entitled “Alvin I. Goldman”. I take it from the shelf and start reading. In great detail, it describes my life as a little boy. It always gibes with my memory and sometimes even revives my memory of forgotten events. I realise that this purports to be a book of my life… I look at the clock and see that it is 3:03… I turn now to the entry for 3:03. It reads: “he is reading me. He is reading me. He is reading me[26] (p. 144).

I now turn to the entry for 3:28. It reads, “He is leaving the library, on his way to the President’s office.” Good heavens, I say to myself, I had completely forgotten about my appointment with the President of the University at 3:30… Since I do have a few minutes, however, I turn back to the entry for 3:22. Sure enough, it says that my reading the 3:28 entry has reminded me about the appointment[26] (p. 144).

Julia peers into her crystal ball and witnesses a future so surprising that she can’t believe it to be the case; nonetheless she’s a diligent sort and records her vision in her diary. Her assistant, Sue, glances in the diary at the end of the day, but isn’t wearing her glasses so misreads Julia’s handwriting, forming the false belief that her twin sister Prue will end up trapped in the cellar. Sue avoids the cellar as she is deathly afraid of the dark, but ventures down to save her more adventurous sibling. In her haste she forgets the keys, thereby trapping herself in the cellar and proving true the vision that Sue—not Prue—would be stuck in a place Julia would never expect her to tread.

3. Inexplicable Loops

Billy is a contestant on a game show with very similar mechanics to the Newcomb Problem: he has a choice between one box and two boxes, and a highly-accurate predictor will predict his choice in advance. However, this particular predictor has access to the future (by time travel, crystal ball or a Gödelian telescope), and this is why she is so accurate—she witnesses the future choice, and thereby knows what Billy will choose. Billy is a stalwart two-boxer: in every conversation with friends and colleagues prior to the game he has insisted he will pick both boxes; he dreams at night of picking both boxes etc. However, the tables are turned when the predictor reveals her prediction to him prior to his choice: she says he will pick one box. As a result of this revelation, Billy decides to pick one box—after all, he reasons to himself, he now knows he will (see Figure 5)21.

Where did the information come from in the first place? Why did the whole affair happen?And concluding,There is simply no answer[1] (p. 149).

No different from questions about where anything originally came from. We can ask about the origin of the atoms that make up [the time traveller]; their timeline is not neatly presented to us. The atoms either go back endlessly, or if the universe is finite, they just start. In either case the question of ultimate origin is as unanswerable as the question of the [loop contents’] origin. What makes us think that when such questions are asked about the loop they are different and ought to be answerable is that the entire loop is open to inspection. Sub specie aeternitatis this difference disappears

4. Improbable Loops

The really puzzling question is, ‘Why does the information work?’… It’s no mystery how the information works… The interesting question is why this is so. And the only possible answer is: coincidence[3] (p. 138).

5. Final Thoughts

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | It may be that these are best understood as a subset of information loops, but I won’t assume as much. Either way, they have some features that aren’t shared by information loops more generally, such as the role that belief plays in their occurrence. |

| 2 | Or will become true, depending on your theory of time. For ease I will assume four-dimensionalism as per Lewis [1], but much of what I say could be adapted to other theories of time. |

| 3 | Whether there are additional free will limitations with this kind of case, or backwards time travel more generally, is a bigger question than I have scope for in this paper. See for example [5]. |

| 4 | |

| 5 | As opposed to conditional or counterfactual knowledge, for example. |

| 6 | It isn’t logically impossible, but may well be theologically impossible (if, as has been suggested, it undermines the providential usefulness of divine foreknowledge). More interesting for my purposes is the claim that MP-violating circumstances are a bad explanation for why events occur as they do, cf. [18]. This is discussed further in §3. |

| 7 | For a particularly explicit example see the conversation between Harry and Dumbledore on Voldemort’s actions in [20] (pp. 740–741) |

| 8 | Whether or not this would count as a case of foreknowledge as opposed to just forebelief (i.e., the belief that you will wear purple, formed as a result of my testimony) will depend on the connection between truth and belief that your epistemology requires. Either way, it isn’t a loop, as the causal chain runs one-way from the belief today to your getting dressed tomorrow. If, however, I said you would wear purple because I’m a time traveller from the future where I saw you wearing purple, then it’d be a loop. |

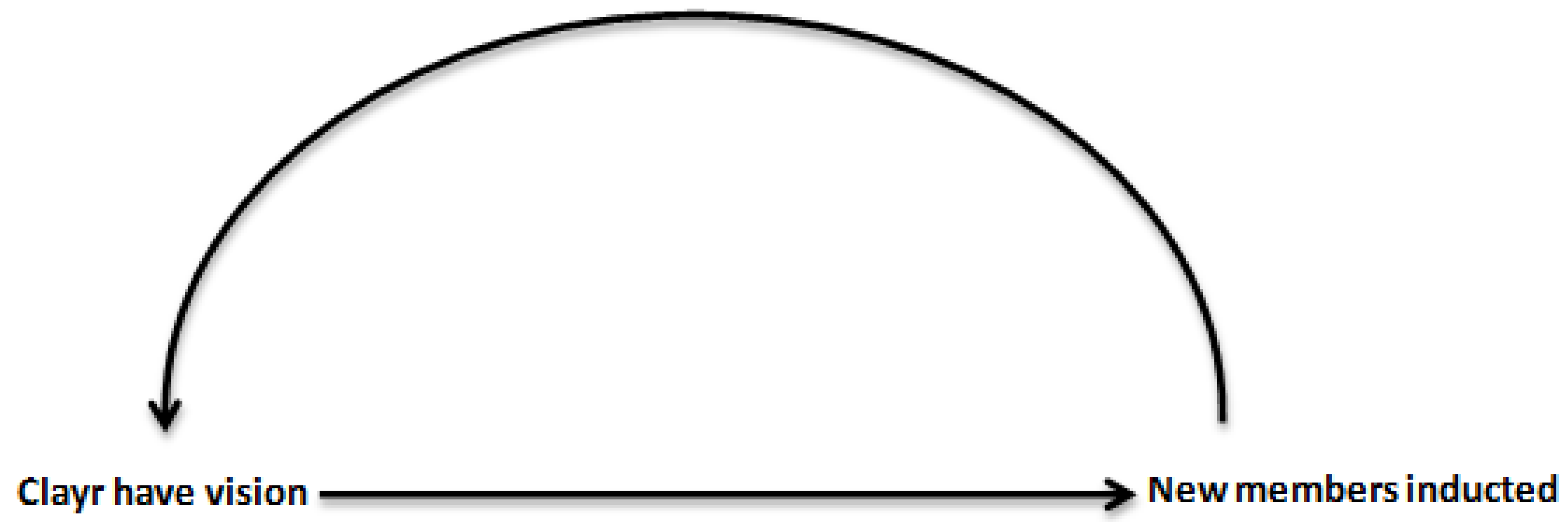

| 9 | This is simplified: we might expect intermediate steps such as ‘Clayr decide who to induct’ between their vision and the induction. |

| 10 | Of course, time travel resulting in knowledge or beliefs about the future and the consequences of that in terms of free will, intentionality and resulting coincidences are discussed in several places, including [3,24,25]. However, that knowledge of (or beliefs about) future facts can generate causal loops (whether in tandem with or independently of time travel) was not the focus of these analyses. |

| 11 | That the thought experiment he provides happens to be such a loop is grist to my mill, but undermines neither the novelty of this paper’s conceptual mapping nor its conclusions. |

| 12 | NB. These are directly analogous to bilking cases in the time travel literature (Cf. [25]). |

| 13 | Likewise, if the author of the book was a supercomputer that could calculate the future based on deterministic laws and a complete understanding of the present (i.e., could have foreknowledge without backwards causation), this would not result in a causal loop. |

| 14 | To think that the relationship between foreknowledge and foreknown events always results in such a loop is what Craig calls “a misunderstanding in which the causal relation between an event or thing and its effect is conflated with the semantic relation between a true proposition and its corresponding state of affairs” [27] (p. 337). |

| 15 | Oedipus does not believe the prophecy is infallible, however, but rather that it will prove true unless he acts to prevent it. Another classic SFP case can be found in W. Somerset Maugham, “An Appointment in Samarra” from Sheppey (1933), as cited in [29] (p. 57): a merchant in Baghdad encounters Death and, based on what he perceives to be a threatening gesture, flees to Samarra to avoid his fate. Death notes that it wasn’t a threatening gesture but “only a start of surprise. I was astonished to see him in Baghdad, for I had an appointment with him tonight in Samarra.” If the merchant hadn’t believed Death was out to get him, he’d have had no reason to go to Samarra. A nice parody occurs in [30] (pp. 77–78): Rincewind the wizard runs into Death, who comments that they have an appointment elsewhere soon and asks if Rincewind would mind going there. Rincewind declines. |

| 16 | These might be the same person, e.g., the Clayr. |

| 17 | Similar cases can be found in [14] and Futurama. Jane grows up in an orphanage; as a teenager she is seduced by a young man, falls pregnant and gives birth to a baby. Jane suffers trauma to her reproductive organs during labour, but doctors discover she is intersex and she undergoes sexual reassignment surgery. Now identifying as a man, Jane is taken back in time by a Bartender, where he meets and impregnates a young woman called Jane. The Bartender then recruits the young man to serve in the Temporal Bureau. The Bartender—revealed to be an older timeslice of the main character Jane—takes the baby back in time to an orphanage; he returns to the Bureau to contemplate his caesarean scar and the creation and recruitment of himself. |

| 18 | This is a version of an example in [1] (p. 149). |

| 19 | They are rarely given a name, but are mostly (including by Lewis) bundled together under the generic name ‘causal loops’. Occasionally they are called ‘ontological loops’, a specific type of ‘closed causal loop’, or the ‘ontological paradox’. Cf. [1] (p. 149). |

| 20 | |

| 21 | A similar line of thinking occurs in [36] (p. 301), with Harry’s confidence in casting the Patronus: Harry finds the confidence to cast the difficult spell because he’d ‘already done it’, but thanks to time travel, the casting he (his earlier self) remembered and the casting he (his later self) performed were one and the same. |

| 22 | Alasdair Richmond raises the possibility that a Kantian noumenal self seems just as capable of ‘willing’ (atemporally) a closed causal chain as a linear one, which lends some credence to the idea that causal loops are no harder to explain sub specie aeternitatis than linear causal chains [38] (p. 102). |

| 23 | More recently, Meyer [2] (p. 260) considered the explicability of causal loops in light of two interpretations of the principle of sufficient reason. |

| 24 | As is the case in [31]. Divine foreknowledge may be a counterexample to this, if one thinks God is omniscient. |

| 25 | This is a common trope in fiction, with vague, misleading or deceptive prophecies. Examples can be found in Macbeth (“need fear none of woman borne”); The Return of the King (Eowyn and the Witch-king of Angmar); Buffy the Vampire Slayer (“Prophecy Girl”); Mostly Harmless (Arthur Dent’s end); Pirates of the Caribbean: On Stranger Tides (Blackbeard’s death). |

| 26 | |

| 27 | There is an argument similar in spirit in [24] (see especially p. 377 re dates on objects). |

| 28 | The first-person/third-person distinction does not map on to the grammar employed. For instance, Oedipus, upon learning of the prophecy, has first-person foreknowledge—although when referring to ‘Oedipus’ we speak of him in the third person. |

| 29 | And it seems less uncanny that beliefs should arise from nowhere, if indeed that’s what’s happening in SFP cases. |

References

- Lewis, D. The Paradoxes of Time Travel. Am. Philos. Q. 1976, 13, 145–152. [Google Scholar]

- Meyer, U. Explaining causal loops. Analysis 2012, 72, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanley, R. No End in Sight: Causal Loops in Philosophy, Physics and Fiction. Synthese 2004, 141, 123–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- French, P.A.; Brown, C. Time Travel. In Puzzles, Paradoxes and Problems; St Martin’s Press: New York, NY, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Wasserman, R. Paradoxes of Time Travel; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.H. Real Time; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1981. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.H. Real Time II; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Mellor, D.H. The Facts of Causation; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Berkovitz, J. On Chance in Causal Loops. Mind 2001, 110, 1–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bourne, C. A Future for Presentism; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Dowe, P. Causal Loops and the Independence of Causal Facts. Philos. Sci. 2001, 68, S89–S97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riggs, P.J. A Critique of Mellor’s Argument against ‘Backwards’ Causation. BJPS 1991, 42, 75–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ismael, J. Closed Causal Loops and the Bilking Argument. Synthese 2003, 136, 305–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Macbeath, M. Who Was Dr. Who’s Father? Synthese 1982, 51, 397–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skzrypek, J. Causal Time Loops and the Immaculate Conception. J. Anal. Theol. 2020, 8, 321–343. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, D.P. Providence, Foreknowledge, and Explanatory Loops: A Reply to Robinson. Relig. Stud. 2004, 40, 485–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, M.D. Divine providence, simple foreknowledge, and the ‘Metaphysical Principle’. Relig. Stud. 2004, 40, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, D. The Providential Usefulness of ‘Simple Foreknowledge’; Rutgers University: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2010; Available online: http://fas-philosophy.rutgers.edu/zimmerman/Providence.Simple.Forek.6.pdf (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Sophocles. King Oedipus. In The Theban Plays; Watling, E.F., Ed.; Penguin Classics: London, UK, 1947; pp. 25–70. [Google Scholar]

- Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Order of the Phoenix; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 2003. [Google Scholar]

- Wachowski, L.; Wachowski, A. The Matrix, Script. 1996. Available online: http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Matrix,-The.html (accessed on 8 September 2021).

- Ehasz, A.; O’Bryan, J. The Fortuneteller. In Avatar: The Last Airbender; Nickelodeon: New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Nix, G. Lirael: Daughter of the Clayr; HarperCollins: Sydney, Australia, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, N.J.J. Bananas enough for time travel? BJPS 1997, 48, 363–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rennick, S. Things mere mortals can do, but philosophers can’t. Analysis 2015, 75, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goldman, A. Actions, Predictions and Books of Life. Am. Philos. Q. 1968, 5, 135–151. [Google Scholar]

- Craig, W.L. Divine Foreknowledge and Newcomb’s Paradox. Philosophia 1987, 17, 331–350. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Effingham, N. Time Travel: Probability and Impossibility; OUP: Oxford, UK, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Dennett, D. True Believers: The Intentional Strategy and why it works. In Mind Design II: Philosophy, Psychology, Artificial Intelligence; Haugeland, J., Ed.; MIT: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Pratchett, T. The Colour of Magic; Transworld: London, UK, 1983. [Google Scholar]

- Heinlein, R.A. —All You Zombies—. The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1959. [Google Scholar]

- McCall, S. An Insoluble Problem. Analysis 2010, 70, 647–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caddick Bourne, E.; Bourne, C. The Art of Time Travel: A Bigger Picture. Manuscrito 2017, 40, 281–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- McAllister, J.W. Does Artistic Value Pose a Special Problem for Time Travel Theories? Br. J. Aesthet. 2020, 60, 61–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gott, J.R., III; Li, L.-X. Can the universe create itself? Phys. Rev. 1998, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rowling, J.K. Harry Potter and the Prisoner of Azkaban; Bloomsbury: London, UK, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Levin, M.R. Swords’ Points. Analysis 1980, 40, 69–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richmond, A. On behalf of spore gods. Analysis 2017, 77, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Aibel, J.; Berger, G. Kung Fu Panda, Script. Available online: http://www.imsdb.com/scripts/Kung-Fu-Panda.html (accessed on 14 September 2015).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Rennick, S. Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. Philosophies 2021, 6, 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies6030078

Rennick S. Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. Philosophies. 2021; 6(3):78. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies6030078

Chicago/Turabian StyleRennick, Stephanie. 2021. "Self-Fulfilling Prophecies" Philosophies 6, no. 3: 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies6030078

APA StyleRennick, S. (2021). Self-Fulfilling Prophecies. Philosophies, 6(3), 78. https://doi.org/10.3390/philosophies6030078