Abstract

The suicide experience combines despair with the perception of suicide as the last option to alter its suffering effectively and actively. Shneidman’s phenomenology understands the suicidal mind in terms of psychological pain, as opposed to focusing on the individual context. This article aims to meet and review information from articles and books published in the area of the Phenomenology of Suicide, mostly between 2017 and 2021. By integrating and relating the different philosophical perspectives of the patient, his or her family, and the mental health worker, it is intended to identify emotions that are common to different groups affected by suicide, regardless of the context, experiences, and means used to commit suicide. The phenomenological description of self-determination experienced in suicide helps to improve the understanding of the suicidal mind, which can be useful in understanding questions that relate to issues such as assisted suicide and suicide prevention. The management of post-suicide consequences, especially the stigma, a cross-cutting challenge for all these groups, benefits from the specialized support of health professionals, either through psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy or support groups.

1. Introduction

The first-person experience of the idea of suicide and suicidal behaviour can be found in contributions from almost every time and place in the world. Descriptions of authors who intended or provoked their own death voluntarily appear scattered throughout different moments in history and in diverse cultures. In Ancient Rome, voluntary and self-inflicted death was an act of honour, while in Europe during the Middle Ages, suicide was considered a crime and a sin and was completely rejected from a moral point of view, and, more recently, it has been variously seen as a symptom or consequence of mental disorder or associated with specific economic and social contexts (van Hooff 2000) [1]. The term “suicide” can be applied in different contexts and to different acts, often being a discriminative attribute in the terms medically assisted suicide, suicide bombings, political acts of suicide, and honour suicides. Any definition of suicide deserves to accept an understanding that allows all subjective and operational elements to be included and will therefore always be heterogeneous (Battin 2015) [1].

Every year, about 1 million people die by suicide worldwide. The exact number is difficult to ascertain, both because of the difficulty in identifying indirect suicide attempts and because of accidental deaths that are interpreted as self-inflicted. It constitutes one of the top 10 causes of death in all age groups and is among the top 3 among adolescents and young adults. The rate of consummated suicide is higher in males and, in turn, more frequent among middle-aged and older adults. However, non-fatal suicide attempts are higher in women, notably adolescents and young adults. Suicide by hanging, firearm, overdose, jumping off cliffs, vehicle impact, and electrocution are some of the most commonly used methods, with the Golden Gate Bridge in California being one of the world’s leading suicide sites, accounting for over 1700 cases since 1937. Suicide attempts by oneself or in a family history of suicide seem the best indicator of suicide risk, justified by a process of habituation or “incorporation”: the more a person becomes familiar with a certain behaviour, through attempts, mental training, or stimulating narratives, the better they perform.

In the 18th century, Goethe, German poet and writer, with his epistolary novel The Sufferings of Young Werther (1774), gave rise to the greatest wave of mass suicides in the history of literature, by creating a protagonist who gives in to his own existential annihilation by an unrequited passion, provoking in young people of the time the same outcome—“Werther Effect”, according to D.P. Phillips (1974). The social dimension of suicide would be worked out later on by Durkheim (1897) [2], showing that to understand it, it is fundamental to know the social context: altruistic—resulting from excessive integration in society and an insufficient individuality, in which the individual not only has the right to commit suicide, but also has this duty; anomic—consequence of the loss of relationship between the individual and society, in the context of great changes in the distribution of wealth, geographical isolation, or cultural alienation; fatalistic—in the face of an imposed and unappealable normative context, when individual aspirations are the target of excessive regulation by society; egoistic—resulting from the evolution of society towards the loss of the collective social focus, designated by Durkheim as “excessive individualism” or “egoism”, and which more recent authors would designate as “new narcissism”, “être pour soi”. The predisposition to suicide would arise when the individual project, inherently fragile and no longer integrated into a social system, disintegrates.

Suicidology, or the study of suicide behaviour and causes carried out by psychiatry and psychology professionals, seems to show that suicide is always, or almost always, pathological, i.e., individuals who voluntarily determine their own death suffer from some type of mental disorder. Mental disorder—namely, depression—is a very frequent characteristic of those who commit suicidal acts [1]. Almost half of all individuals who die by suicide were assessed by a mental health professional in the month prior to their death [3]. Although depression and bipolar disorder are the most common disorders among people who attempt suicide, it can also occur among college students [4], people with substance abuse disorders or schizophrenia [5], who find suicide a way to escape the intolerable pain that characterises mental illness, trauma, loss, rejection, or deceptions.

However, it is very difficult to find an immutable and universal element in all suicide experiences because, for example, not all clinically depressed people attempt suicide. In fact, if we statistically control for some symptoms, the diagnosis of depressive episode ceases to be a risk indicator, motivating a deeper discussion on the causal processes that will certainly be heterogeneous [6]. Nevertheless, although the circumstances and methods used may vary, there is evidence that some elements are constant in suicide. Edwin Shneidman, one of the founders of modern Suicidology, named psychological pain (“psychache”) as a necessary element of suicide and described it as introspective experience of negative emotions—despair, fear, sadness, shame, guilt, loneliness, and loss [7,8]. Thomas Joiner (2005), van Orden (2010), among others, have considered that psychache arises out of unmet human needs [1]. The “need to belong”, described by Baumeister and Leary (1995), when failed and coupled with the acquired capacity for suicide, leads to the death wish [5].

The Phenomenology of Suicide

Phenomenology, a philosophical area developed by Edmund Husserl, values the study of experience unreflected by outside agents (including ideas and medical or technical jargon), the attempt to isolate and detach it from all assumptions of existence or causal influence, and, through an unnatural “epoché” attitude, to uncover its essential structure.

In the area of suicide, Shneidman’s contribution (1993), in defining “psychache” as the main ingredient of suicide, is relevant to phenomenology because it suggests that if individuals in despair could stop consciousness and live, they would opt for this solution, revealing suicide as an attempt to escape intolerable emotions and not a movement towards death. Suicide emerges as the ideal solution in the face of an inner dialogue in which the subject exhaustively analyses various options to escape suffering and, in this way, the suicidal subject is, albeit in an aversive and uncomfortable way, self-conscious [7]. The awareness that the “self” is inadequate generates negative emotions and the desire to escape from self-consciousness in this state, and suicidal self-destructive behaviour is considered an escape from the “self” [5]. It also suggests that in the attempt at cognitive deconstruction (restricted temporal focus, concrete thinking, immediate and proximate goals, cognitive rigidity, and rejection of meaning), which aims to prevent further awareness of its negative emotions, is marked by irrationality and disinhibition, making drastic measures possible.

This awareness of oneself as insufficient and the state of despair or “psychache” leads the subject to value suicide as appealing because it is seen as a calming effect that offers a last and reliable possibility to alter one’s own reality actively and effectively. Everything that could be altered now seems to have failed or to be fruitless, but suicide can still be actively triggered by the self (or by another person actively delegated by the self), justifying that in a suicidal act there is, at least in a “basic” or “minimal” way, a sense of self-determination [9]. By offering a possibility beyond the horizontalisation of temporality (in which there would be no comfortable situation), suicide sustains the subject and confers freedom—“The idea of suicide is a great comfort: it helps to get through a bad night.” Friedrich Nietzsche (1844–1900) [9].

Suicide, despite its positive valuation, and in that sense attractiveness, is therefore not necessarily judged by the self as a correct act (or in favour of his existential project). The impossibility of re-evaluating suicidal behaviour retrospectively limits us to understanding whether it was ever self-determined—only then could it be guaranteed that the determination is maximum or full by having a retrospective reflection [9]. This impossibility is also a final obstacle of the suicidal act once the subject recognises its precipitous and sudden nature that cannot be rethought. Considering rationality to suicide would only be possible if there is, “objectively”, no other chance to alter pain and suffering [9]. Indeed, and as Hume writes—suicide can even be judged as a “remedy” if death is seen only as a “horror”. However, there are criticisms, since considering the pre-reflexive evaluation of a self-inflicted death as “relief” (Hans), “liberation” (Améry), or “remedy” (Hume) requires full awareness which may not be possible if the subject is in despair [1]. The ambivalence of the suicidal mind is also frequently being characterised by a change of mind at the moment of the suicidal act or immediately after its attempt [10]. This makes it difficult to understand their intention since an explicit intention to survive and to kill oneself may coexist. The subject may then remain unsure whether suicide is really the last option for rescue or whether the continuous and unbearable despair ends with self-inflicted death. Two conflicting interests are thus frequent in the same person at the same time [9]. This ambivalence characterises suicide in the absence of psychiatric disorders—there usually the suicidal mind experiences unbearable psychological distress. There are few studies on the phenomenology of suicide in severe mental illness, and even in depression or psychosis the patient may continue to seek treatment and in the expectation of getting better and therefore not think about ending their life [11].

2. The Different Philosophical Perspectives—Patient, Family, and Healthcare Professionals

2.1. The Patient

Over time, the study of suicide has allowed us to understand the sensations inherent in the suicidal experience, highlighting the similarities between the various experiences—namely, in the way the subject analyses himself and the world around him.

Suicidal ideation, which seems to constitute a wider set than just suicidal thoughts, has been, over time, the focus of research on suicide in the first person. Suicidal thoughts can arise in the absence of suicidal risk and do not, by themselves, and in the absence of feelings, lead to suicidal acts [12]. Attempting to resist these thoughts is part of suicidal feelings. However, there are other perspectives, particularly studies on suicidal feelings. As a feeling, it seems to comprise an interruption in the experience of the self, being described by individuals with previous suicide attempts as a bodily experience that restructures the experience of the self, the world, and those around it. A change of a transformative nature is established in which no thought, emotional response, or perception is left completely unchanged [13].

Although each suicidal experience has a unique framework, there is a combination of common factors—namely, (1) loss of clarity and/or coherence of one’s sense of identity; (2) rupture in reciprocity between “self” and world; (3) depletion of mental resources; and (4) disruption of embodiment—“The person I am ‘normally’ is gone and I am a fragmented human being without hope, direction or future… Where have I gone and what is happening to me?” [12]. At this point, the basic assumption of an integrated “self”, usually taken for granted, is questioned, further manifesting an absence of coherence between the social/public “self” and the suicidal “self” that remains up to the act, either immediately visible or actively hidden.

This considered cleavage in the self may explain how external positive considerations directed to support the suicidal individual are experienced as useless or empty of meaning since they are addressed to the social and public “self” that no longer inhabits the subject, in contrast with negative criticism, which is often experienced as ego-sympathetic and thus acquires greater sentimental intensity for the hidden suicidal self [12]. Therefore, in suicide there are also moments of inner conflict in which the two selves described above coexist—“When I am well, I am not aware of the division of my ‘self’ into parts. If I am very depressed or having suicidal thoughts, I may feel out of place. So contrary ideas may arise—the rational side of me (perhaps the normal ‘me’) is sure that suicide is no solution, but there is another entity in me that issues thoughts about the easiest solution—ending everything” [14].

It is also possible for a sense of depersonalisation to arise—as if living distanced from oneself by the different parts of the “self” that now manifest—and there are even dissociative symptoms, as if actions become observed behaviours separate from one’s own agent—“I didn’t feel connected with myself, it was like I was a robot and suicide was the automatic response” [12]. The altered relationship with the outside, often as a breakdown of reciprocity, determines a distortion or attenuation of the impact of the world and others. The latter are often experienced as indifferent, inaccessible, hostile, or manipulative—“I am immune to any stimuli, be they people, colours, tastes.... I am separate from everything and everyone, detached and unable to interact.” “Nothing can enter or leave my mind, I am emotionally isolated, on an island and with no opportunity for rescue” [12].

In the suicidal experience, the bodily dimension of the individual is often overlooked but seems to be fundamental, being a focus of discomfort, pain, turbulence and fragility [1]. The body becomes difficult to inhabit and a desire to escape it arises—“I physically tremble as the battle takes place inside.... I spend hours fighting with myself”. This tumultuousness will subsequently give rise to sensations of absence (loss of “leib” or lived body) experiencing the body as physical (“korper”), numb, resisting movement or even empty and hollow—“It’s like I’m an empty, lifeless shell. It wouldn’t make any difference if I died anyway” [12].

The suicidal individual, despite living as an object, appears to maintain the subjectivised “Other”—that is, demonstrating towards them concern and care. This experience acts as the final barrier to suicide by manifesting a desire to prevent those closest to them from suffering from its suppression—the suicidal “self” is further endowed with an active role in the lives of other individuals, thus constituting a protective factor from suicide [12]. However, it can be deconstructed either by overvalued or obsessive ideas of the uselessness of the self or by the loss of reciprocity in social interactions (“The awareness that there are people around me who care about me and would be devastated if they lost me becomes impossible to believe or recognise”), as well as the inability to emotionally regulate that which is associated with oppressive feelings. Alongside this, trying to prevent the expression of these disorganised emotions can reduce their physical expression by concealment [13].

There also arises an experience of mental “burnout” derived from the frustrated desire to take control over negative feelings and thoughts [15]. Thus, parts of the daily automatisms and common sense, usually invisible and automatic (usually requiring no mental effort), can acquire a disproportionate complexity, adding to the present physical and psychic exhaustion and highlighting the idea of escape as the only possibility of rest—“I can’t think normally, my brain feels overloaded, so exhausted that my body has become weak (...)”.

Finally, in the relationship with the world, we observe a change in the salience of the elements of the real that serve the suicidal individual’s purpose: bridges, tall buildings, train lines, drugs, and suffering-relieving drugs or sharp objects [11]. All other elements reduce their presence, and so the suicidal individual finds it difficult to concentrate on habitual actions, continuously interrupted by suicidal thoughts and the redirection of attention to enabling elements. There even emerges a sense of passivity, in that acceding to a suicidal impulse equates to “letting nature have its way”, signalling a loss of embodied self-esteem [12].

There is a need for a paradigm shift that should emphasize the mental pain in individuals as the focus of the suicide risk [16].

2.2. The Healthcare Professional

Regardless of patient approach, length of contact, and professional experience, the suicide of a patient in the care of a healthcare professional constitutes a difficult and often traumatic time [3]. In addition to doctors, all healthcare professionals involved in the follow-up of the suicidal individual often go through a period of intense emotions after suicide, marked by shock, guilt, isolation, loss of confidence, insomnia, and doubt. In psychiatry, this situation is particularly prevalent, and most doctors experience at least one suicide. In cases of diminished professional experience, there is a particular vulnerability to the negative impacts of a patient’s suicide, manifested by some of the most critical reactions [17].

In the face of a patient’s suicide, there are several phases that in part approximate those commonly considered of bereavement. In the first days, the initial trauma/personal crisis/shock phase is immediate and dominated by strong but undifferentiated emotional states such as confusion, disorientation, depersonalisation, disbelief, denial, distraction, fear of guilt, fear of other suicides, helplessness, shock [18].

In this emotional management process, some people try to temporarily withdraw from work, refuse to follow up patients with a high suicidal risk, or change their clinical attitude in order to prevent a new episode more effectively. Within weeks to the second month after the suicide, they are marked by turbulence, floods of anger, guilt, anxiety, and depressive moods. Feelings of doubt, shame, grief, sadness, and lack of concentration and productivity remain, and there may be sleep and appetite problems, distancing from patients, behavioural changes in relation to different clinical situations, and even an increase in alcohol intake or other self-destructive coping strategies. Several months after suicide, the renewed commitment phase emerges, marked by renewal around the scars of the trauma, which characterises a healthy recovery. However, maladaptive behaviour marked by prolonged helplessness, insecurity, and doubt may sometimes endure [19].

Although some degree of inexperience and adequate knowledge regarding suicide is recognised, it can present a significant dilemma for even the most experienced professionals [4]. The inability to prevent it relates to the fact that it is neither fully understood nor preventable and that around 25% of patients never disclose suicidal ideation. Moreover, self-harm and suicide attempts can be exacerbated by strategies considered preventive, such as hospitalisation and patient surveillance [4]. In this sense, suicide cannot be fully prevented.

After experiencing a patient’s suicide, psychiatrists often seek assistance either through colleagues, friends, family members, or other professionals, which correlates positively with the number of observed suicidal episodes [3].

At an age when cardiovascular diseases and neoplasms have little representation for mortality, suicide represents the leading cause of death in children and adolescents who have psychiatric follow-up. However, less than 20% of children who commit suicide had follow-up in health services, which demonstrates a gap in health care [17]. At these ages suicide is particularly distressing for healthcare professionals in view of the huge value of YLD and also the impulsive and often unexpected nature of these events.

However, the existing stigma around suicide is considered one of the primary factors that exacerbate emotional distress and prevent the application of post-suicide intervention strategies that favour overcoming it and minimising the consequences of the episode [20].

2.3. The Family

Suicide, as it is often unexpected for those around the individual, motivates feelings of sadness, regret, rejection, guilt, disconnection, shame, and stress that can last for years, sometimes never being fully resolved [21]. Often seen as the representation of failure, suicide gives rise to stigma that significantly affects those who survive and go through the grieving process [22], in turn making it difficult for them to seek help and to expose their experiences of bereavement through suicide [23].

The term “survivor” of suicide refers to the subject who suffers the transformation prompted by the suicide of someone with whom they had significant, close, and regular contact [4]. Cerel and Campbelll (2008) suggested that between 5 and 100 survivors are affected by each suicide, including nuclear and extended family members, colleagues, friends, and acquaintances [4]. In this sense, it is estimated that between 48 and 500 million people annually go through a period of bereavement due to suicide [24].

Complicated grief arises from a prolongation of acute grief, giving rise to suffering and impairment in the individual’s functioning [25]. To the feelings of loss, sadness, and loneliness are added, in the case of suicide survivors, guilt, confusion, shame, trauma, and stigma, which deprive them of the resources needed to overcome the suicide. Some studies suggest that about 10–20% of survivors develop complicated grief, having increased rates of psychiatric comorbidities such as major depression and post-traumatic stress disorder [19].

There is a need on the part of suicide survivors to attribute meaning to the suicidal act and justify this decision, which can lead to overvaluing one’s own responsibility and ruminating that intensifies feelings of guilt [26]. This is a disturbing period, marked by confusion and shock, being a risk to the survivors’ health [27], and establishing the survivors themselves a high-risk group for suicide due to the difficulty they feel in restoring balance [28].

In the case of the victim’s family, there is often a higher incidence of rejection, guilt, shame, and stigma [18]. Guilt, shame, and stigma are particularly intense in the case of parents who lose a child to suicide [29], relative to other groups, especially when children or adolescents are involved [30]. On the other hand, reduced guilt and greater ease of understanding is identified in cases where the suicide was associated with a diagnosed psychiatric disorder.

In the case of the partner of the suicidal individual, feelings of rejection and guilt prevail [31], and in the case of children who lose their parents to suicide, the feeling of abandonment stands out [32].

On the other hand, anger is one of the most frequent emotions in all groups, either towards the person who committed suicide (for the absence of a request for help, for example), towards the person for not having been able to change the outcome, towards relatives, acquaintances, and health care professionals (mainly for not having been able to prevent the death), or towards the world in general [31]. Thus, although the mourning period may be marked by numerous emotions, which often alternate over time, it is possible to identify a pattern among survivors based on the degree of attachment to the suicidal individual [33].

Given the unique insight that survivors’ emotional experiences offer into the impact of completed suicide, a study conducted by Peters et al. in 2013 [4] used a qualitative methodology that included interviews of individuals aged between 25 and 65 years old, with the purpose of analysing different perspectives in the 12 months following the suicide of someone close to them. Three main arguments were highlighted: the clear intention to end one’s own life; the absence of support from health services; and the feeling of omission of information about the patient by health professionals.

The generality of participants identified the imminent suicide risk, although they felt unable to obtain appropriate assistance, which they considered central in preventing death. The lack of assistance was attributed to the need for maintaining patient confidentiality; however, although it is clear that there is ambiguity between the boundaries of confidentiality and the duty of care for those who have attempted suicide or who have suicidal ideation, in certain circumstances it is necessary to disclose personal information to the closest individuals and other professionals in order to jointly prevent possible harm [34]. It is essential that health professionals take into account the concerns expressed by those accompanying the suicidal subject in order to ensure their safety [35].

Occasionally, the final act of suicide may be witnessed by survivors. In these circumstances, the grief that characterises the period of bereavement is marked by fear, horror, and vulnerability, which indicates a greater likelihood of developing post-traumatic stress disorder [36]. Compared with non-traumatic bereavement situations, despair, disbelief, anxiety, hyperexcitement, and dysphoria are also intensified and prolonged, which worsens the prognosis of bereavement.

The pain motivated by the loss to suicide, combined with shame, rejection, anger, and sense of responsibility, among others, create a higher need for escape among survivors. In this sense, of all the emotions provoked by the suicide of someone close, it is important to highlight the high risk of suicide experienced by survivors [37].

Suicide is a known target of stigma despite recent efforts to combat it. Dialoguing about loss is, for many, essential for recovery, so obstacles at this level are additional impediments to the grieving process [38].

It is recognised in the literature that survivors of suicide receive considerably less support than those going through a period of grief for different reasons [39]. There are still objections to effective prevention and support for survivors, a worrying aspect given that they are a high-risk group for suicide [40]. In this sense, although the evidence of the results of follow-up of this group is limited, some aspects are emphasised—namely, the initial attention focused on the traumatic suffering, the benefit of support groups [41], the valorisation of the family context [20], and also the importance of pharmacotherapy and psychotherapy [42].

Increased visibility and transparency of suicide loss experiences have contributed to reduced shame and stigma [25]. The provision of adequate spaces for communication has been highlighted as one of the main reasons for survivors’ participation in studies related to suicide bereavement, given the difficulty in accessing mental health resources [24].

Therefore, adequate preparation of all professionals is imperative, not only in developing suicide prevention strategies in at-risk groups [43] but also in recognizing the intensity and emotional complexity of suicide grief [23].

Although some biomarkers to predict suicide risk have been studied, none are currently validated [15]. Restricting means of suicide and preparing health professionals are some of the most appropriate methods [38], the latter being marked by psychotherapy, pharmacotherapy, and directing the individuals involved to areas that promote adequate support from an early age [44].

3. Materials and Methods

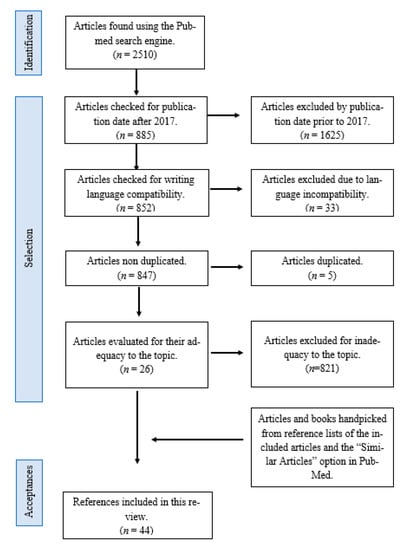

This was a narrative review of articles and books published between the years of 2017 and 2021 in the area of suicide, written in English and Portuguese. The MESH PubMed keywords used included ((Suicide) and (Perspectives)), ((Suicide) and (Phenomenology)). The full database was assessed by two researchers (L.M. and A.M.) according to our inclusion criteria: language, publication date, and aim of topics to be covered. The books that were included are related to suicide phenomenology and neurobiology. Figure 1 presents our selection process.

Figure 1.

References selection criteria.

With this review, we confess that our selection may have been subjective.

4. Conclusions

Shneidman’s phenomenology understands the suicidal mind in terms of psychological pain, interpreting suicide as a last attempt to escape intolerable emotions.

Among each of the groups affected by the suicide, there are similar emotions during the process, such as the stigma and regret of the family, the guilt of the health professional, and the sadness and despair of the suicidal individual.

The management of post-suicide consequences benefits from the specialized support of health professionals, either through psychotherapy and pharmacotherapy or support groups.

Our review suggests that in clinical practice, a phenomenological approach might not only serve as an epistemic necessity for identifying and exploring emotions underlying the experience of suicide (the before and after) but also help in the clinical relationship to clarify several complex emotional states. Together, clinical and patient insights might ultimately help in primary and secondary prevention of suicide—a new paradigm.

Author Contributions

Both authors developed all sections of this article. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

There are no data.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge the role of juri of a Master Thesis of the University of Medicine in improving the quality of the paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Pompili, M. Phenomenology of Suicide. Unlocking the Suicidal Mind, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Durkheim, E. Suicide, a Study in Sociology, 1951 ed.; Spaulding, J.A.; Simpson, G., Translators; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 1897; ISBN 0710033117. [Google Scholar]

- Erlich, M.D.; Rolin, S.A.; Dixon, L.B.; Adler, D.A.; Oslin, D.W.; Levine, B.; Berlant, J.L.; Goldman, B.; Koh, S.; First, M.B.; et al. Why we need to enhance suicide postvention. Evaluating a survey of psychiatrists’ behaviors after the suicide of a patient. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Peters, K.; Murphy, G.; Jackson, D. Events prior to completed suicide: Perspectives of family survivors. Issues Ment. Health Nurs. 2013, 34, 309–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baumeister, R.F. Suicide as escape from self. Psychol. Rev. 1990, 90–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Berlim, M.T.; Mattevi, B.S.; Pavanello, D.P.; Caldieraro, M.A.; Fleck, M.P.A.; Wingate, L.R.; Joiner, T.E. Psychache and suicidality in adult mood disordered outpatients in brazil. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2003, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidman, E. Suicide as psychache: A clinical approach to self-destructive behavior. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 1993, 181, 145–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneidman, E. The psychological pain assessment scale. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 1999, 29, 287–294. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Schlimme, J.E. Sense of self-determination and the suicidal experience. A phenomenological approach. Med. Health Care Philos. 2013, 16, 211–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Naherniak, B.; Bhaskaran, J.; Sareen, J.; Wang, Y.; Bolton, J.M. Ambivalence about Living and the Risk for Future Suicide Attempts: A Longitudinal Analysis. Prim. Care Companion CNS Disord. 2019, 21, 18m02361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pompili, M. Exploring the phenomenology of suicide. Suicide Life Threat Behav. 2010, 40, 234–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benson, O.; Gibson, S.; Brand, S.L. The experience of agency in feeling of being suicidal. J. Conscious. Stud. 2013, 20, 56–79. [Google Scholar]

- Cannon, K.E.; Hudzik, T.J. Suicide: Phenomenology and Neurobiology, 1st ed.; Springer International Publishing: New York, NY, USA, 2014; Volume 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orbach, I.; Mikulincer, M.; Gilboa-Schechtman, E.; Sirota, P. Mental pain and its relationship to suicidality and life meaning. Suicide Life-Threat. Behav. 2003, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nugent, A.C.; Ballard, E.D.; Park, L.T.; Zarate, C.A. Research on the pathophysiology, treatment, and prevention of suicide: Practical and ethical issues. BMC Psychiatry 2019, 19, 332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pompili, M. The increase of suicide rates: The need for a paradigm shift. Lancet 2018, 474–475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Al-Mateen, C.S.; Jones, K.; Linker, J.; O’Keefe, D.; Cimolai, V. Clinician response to a child who completes suicide. Child Adolesc. Psychiatric. Clin. N. Am. 2018, 27, 621–635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feigelman, W.; Cerel, J. Feelings of Blameworthiness and Their Associations With the Grieving Process in Suicide Mourning. Front Psychol. 2020, 11, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Young, I.T.; Iglewicz, A.; Glorioso, D.; Lanouette, N.; Seay, K.; Manjusha, I.; Zisook, S. Suicide bereavement and complicated grief. Dialogues Clin. Neurosci. 2012, 14, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andriessen, K.; Krysinska, K.; Rickwood, D.; Pirkis, J. “It Changes Your Orbit”: The Impact of Suicide and Traumatic Death on Adolescents as Experienced by Adolescents and Parents. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 9356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutra, K.; Preis, L.; Caetano, J.; Santos, J.; Lessa, G. Experiencing suicide in the family: From mourning to the quest for overcoming. Rev. Bras. Enferm. 2018, 71 (Suppl. 5), 2146–2153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eisma, M.; Riele, B.; Overgaauw, M.; Doering, B. Does prolonged grief or suicide bereavement cause public stigma? A vignette-based experiment. Psychiatry Res. 2019, 272, 784–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scocco, P.; Idotta, C.; Totaro, S.; Preti, A. Addressing psychological distress in people bereaved through suicide: From care to cure. Psychiatry Res. 2021, 300, 113869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitman, A.; Osborn, D.; King, M.; Erlangsen, A. Effects of suicide bereavement on mental health and suicide risk. Lancet Psychiatry 2014, 1, 86–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Lev-Ari, L. Is There Anybody Out There? Attachment Style and Interpersonal Facilitators as Protective Factors Against Complicated Grief Among Suicide-Loss Survivors. J. Nerv. Ment. Dis. 2019, 207, 131–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stone, S. Supporting Families and Providers When Suicide Occurs. Am. J. Hosp. Palliat. Care 2019, 36, 264–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Orford, N. Grief after Suicide. JAMA 2020, 323, 1720–1721. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frumkin, M.; Robinaugh, D.; LeBlanc, N.; Ahmad, Z.; Bui, E.; Nock, M.; Simon, N.; McNally, R. The pain of grief: Exploring the concept of psychological pain and its relation to complicated grief, depression, and risk for suicide in bereaved adults. J. Clin. Psychol. 2021, 77, 254–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shields, C.; Russo, K.; Kavanagh, M. Angels of Courage: The Experiences of Mothers Who Have Been Bereaved by Suicide. Omega 2019, 80, 175–201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hagstrom, A.S. Research-Based Theater and “Stigmatized Trauma”: The Case of Suicide Bereavement. Front. Psychol. 2020, 11, 1129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Creighton, G.; Oliffe, J.L.; Bottorff, J.; Johnson, J. “I should have…”: A photovoice study with women who have lost a man to suicide. Am. J. Men’s Health 2018, 12, 1262–1274. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ross, V.; Kõlves, K.; Leo, D. Exploring the Support Needs of People Bereaved by Suicide: A Qualitative Study. Omega 2021, 82, 632–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hagstrom, A.S. “Why did he choose to die?”: A meaning-searching approach to parental suicide bereavement in youth. Death Stud. 2019, 43, 113–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Frey, L.; Fulginiti, A. Talking about suicide may not be enough: Family reaction as a mediator between disclosure and interpersonal needs. J. Ment. Health 2017, 26, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mento, C.; Silvestri, M.; Muscatello, M.; Rizzo, A.; Celebre, L.; Bruno, A.; Zoccali, A. Psychological pain and risk of suicide in adolescence. Int. J. Adolesc. Med. Health 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamdan, S.; Berkman, N.; Lavi, N.; Levy, S.; Brent, D. The Effect of Sudden Death Bereavement on the Risk for Suicide. Crisis 2020, 41, 214–224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levi-Belz, Y.; Aisenberg, D. Interpersonal predictors of suicide ideation and complicated-grief trajectories among suicide bereaved individuals: A four-year longitudinal study. J. Affect. Disord. 2021, 282, 1030–1035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naguy, A.; Elbadry, H.; Salem, H. Suicide: A Précis! J. Family Med. Prim. Care 2020, 9, 4009–4015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Linde, K.; Treml, J.; Steinig, J.; Nagl, M.; Kersting, A. Grief interventions for people bereaved by suicide: A systematic review. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0179496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Kucukalic, S.; Kucukalic, A. Stigma and Suicide. Psychiatr. Danub. 2017, 29 (Suppl. 5), 895–899. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cipolletta, S.; Entilli, L.; Bettio, F.; Leo, D. Live-Chat Support for People Bereaved by Suicide. Crisis 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, J.; Hong, S.; Hong, H. The Impact of Referral to Mental Health Services on Suicide Death Risk in Adolescent Suicide Survivors. Soa Chongsonyon Chongsin Uihak 2020, 31, 177–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ivbijaro, G.; Kolkiewicz, L.; Goldberg, D.; Riba, M.B.; N’jie, I.N.; Geller, J.; Kallivayalil, R.; Javed, A.; Švab, I.; Summergrad, P.; et al. Preventing suicide, promoting resilience: Is this achievable from a global perspective? Asia Pac. Psychiatry 2019, 11, e12371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wainwright, V.; Cordingley, L.; Chew-Graham, C.; Kapur, N.; Shaw, J.; Smith, S.; McGale, B.; McDonnell, S. Experiences of support from primary care and perceived needs of parents bereaved by suicide: A qualitative study. Br. J. Gen. Pract. 2020, 70, e102–e110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).