Abstract

In our complex and highly connected world, educating for life—that is, educating students with knowledge, skills, and competences infused with practical wisdom (PW) and ethical and moral values—is essential. The paper seeks to answer the question: how could university education facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world? The methodology involves case study research (CSR) based on both secondary and primary data. The missions, visions, and values of fourteen public Finnish universities are analyzed for PW. The findings demonstrate that universities, by becoming more open, unbounded, and enacting organizations, and by enhancing collaboration with businesses, could foster the cultivation of PW in higher education (HE). The novelty of this paper is the creative communication of the case study, where kairos, logos, pathos, and ethos are used to explore a new reality for HE. The article contributes to the contemporary discourses in the literature on the future of HE. Educators in HE need to transform from knowledge workers to wise leaders, wisdom workers, creators, empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers. The context of the case study research makes it difficult to generalize. Therefore, international, comparative research is used to complement the findings. The eight-stage change process applied to universities and HE could help in solving the urgent problems of society and facilitating progress to a wiser and better world.

Non scholae sed vitae discimus.

(We do not learn for school, but for life.)

1. Introduction—Kairos—Defining an Affirmative Topic

This research paper focuses on searching for practical wisdom (PW) in higher education (HE) and on the changing role of universities and HE. I seek to answer the question: how could university education facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world? First, I briefly explore the concepts of wisdom, PW, and the need for PW in HE.

1.1. What Is Wisdom?

Wisdom has always been vital throughout human history. Justice, fortitude, temperance, and wisdom (prudence) are human virtues. It is commonly believed that the main goal of wisdom is to contribute not only to individuals but to the community and society as a whole. The Merriam-Webster Dictionary [1] defines wisdom as “(1) the ability to discern inner qualities and relationships (insight, judgment, knowledge); (2) a wise attitude, belief, or course of action; and (3) the teachings of the ancient wise men (sic)”.

Wisdom research in psychology began to flourishing again in the 1980s. Researchers explored, for example: the three dimensions of wisdom, i.e., affective (e.g., sympathy and compassion for others), reflective (e.g., overcoming subjectivity and reducing ego-centeredness), and cognitive (e.g., seeing reality and understanding truth) [2]; the six qualities of wisdom, i.e., reasoning, sagacity, learning, judgment, quick use of information, and perspicacity [3]; three conceptualizations of wisdom, i.e., wisdom of life (sophia), wisdom of knowledge (episteme), and wisdom of practice (phronesis) [4]; the meanings of wisdom [5]; the features of wisdom [6,7,8]; the characteristics of a wise person [9,10]; cultural context and wisdom [11]; and so on.

Wisdom has six features according to Baltes and Staudinger [6] (p. 132): (1) strategies and goals involving the conduct and meaning of life; (2) the limits of knowledge and the uncertainties of the world; (3) excellence of judgment and advice; (4) knowledge with extraordinary scope, depth, and balance; (5) the search for a perfect synergy of mind and character; and (6) balancing the good or well-being of oneself and that of others. The researchers Bangen, Meeks, and Jeste [8] (p. 1257), in their extensive literature review of wisdom definitions and their common subcomponents, categorized authors’ definitions of wisdom as based on decision-making/knowledge (23), prosocial attitudes (21), self-reflection (19), the acknowledgement of uncertainty (16), emotional homeostasis (13), tolerance (7), openness (5), spirituality (5), and the sense of humor (3). The numerals following each subcomponent of the definition of wisdom above indicate the frequency of the specific subcomponent found in the reviewed studies. Bangen et al. concluded that “the most commonly cited subcomponents, which appeared in at least half of the definitions, relate to social decision-making/knowledge of life, prosocial values, reflection, and acknowledgement of uncertainty” [8] (p. 1262).

According to the philosopher Maxwell [12], “Wisdom includes knowledge and understanding but goes beyond them by also including: the desire and active striving for what is of value, the ability to see what is of value, actually and potentially, in the circumstances of life, the ability to experience value, the capacity to use and develop knowledge, technology and understanding as needed for the realization of value. Wisdom, like knowledge, can be conceived of, not only in personal terms, but also in institutional or social terms. We can thus interpret wisdom-inquiry as asserting: the basic task of rational inquiry is to help us develop wiser ways of living, wiser institutions, customs and social relations, a wiser world” [12] (p. 66).

Wisdom can also be understood as an ‘attitude’. Weick [13] (pp. 345–379) argues: ”Wisdom, can be defined conceptually as a balance between knowing and doubting, or behaviorally as a balance between too much confidence and too much caution” or doubt [13] (p. 366). He points out that, through perceptions, events and experiences (i.e., context) lead to reflections—that is, the content of wisdom—and then to judgment—that is, about the process of wisdom. Weick reasons that “wisdom maybe an attitude rather than a body of thought … because it implies that people can improve their capability for wise actions” [13] (p. 367). In many organizations the attitude of overconfidence in knowledge and knowing is very common and, consequently, an attitude of wisdom is rare; furthermore, wisdom could even be discouraged as overconfidence grows. This could be the case in universities, as they are organizations where overreliance on knowledge-inquiry increases confidence and, as a consequence, diminishes wisdom-inquiry. Taking the attitude of questioning, doubting what we already know (i.e., becoming less confident in what we already know), embedding new learning and new ideas, and improvising actions could move organizations toward wisdom.

1.2. What Is Practical Wisdom?

I argue that the three psychological dimensions of wisdom [2] (i.e., cognitive, affective, and reflective) and the three philosophical views of wisdom [4], namely wisdom of life (sophia), wisdom of knowledge (episteme), and wisdom of practice (phronesis), are highly relevant to HE. My aim is to search for PW in HE; therefore, it is necessary to define what kind of PW is most relevant. Since the 1990s, phronesis, as one dimension of prudence, has experienced a revival and attracted growing attention in management and leadership practices and research literature (e.g., [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27]).

Recently, Bachmann, Habisch, and Dierksmeier [28], in an interdisciplinary literature review, examined PW from philosophical, theological, psychological, and management (i.e., leadership, decision making, strategy, organizational studies, and human resource management) perspectives. Bachmann et al. [28] (p. 160) concluded that PW “guides towards an organizational setting where excellence in judgment and in character, personal development and interpersonal relations, economic success and social responsibility can emerge”. Phronesis plays the role of guiding and synthesizing of skills (techne) and theoretical knowledge (episteme). However, to act upon PW there is a need “to pay attention not only to instrumental knowledge and abstract techniques, but also to social, cultural, moral aspects and to the students’ personal development” [28] (p. 160). Therefore, the role of education is fundamental in cultivating future generations’ capacity for PW [29,30].

1.3. Why Is There a Need for Practical Wisdom in Higher Education?

Educating for life—that is, educating students with knowledge, skills, and competencies infused with PW and ethical and moral values—has become of the utmost importance. Therefore, there is a need for PW in ethical decision making, complex problem solving, and in handling the challenges and unpredictability of life. The world is becoming extremely complex and highly interconnected, with wicked problems in need of wiser and better solutions. More than ever before, the world needs wisdom. In a survey on world challenges [31], experts identified fifty major problem areas for humanity in the 21st century and among them were: artificial intelligence, cities and global development, health and humanity, social inequality, global political instability, threats to democracy, wars, genocides, terrorism, nuclear and biological weapons, climate change, waste disposal, and species extinction. Maxwell [32] reasoned that the main cause of these global problems is that we have failed to learn how to create a civilized world. In this paper, I argue that the solution could be ‘educating for life’, which means enabling future generations through wisdom, PW, knowledge, skills, and competencies not only to identify but to act, and seeking to solve authentic and wicked life problems. Therefore, academia and education should play an important role in cultivating the PW of future leaders, managers, experts, and practitioners [29,33].

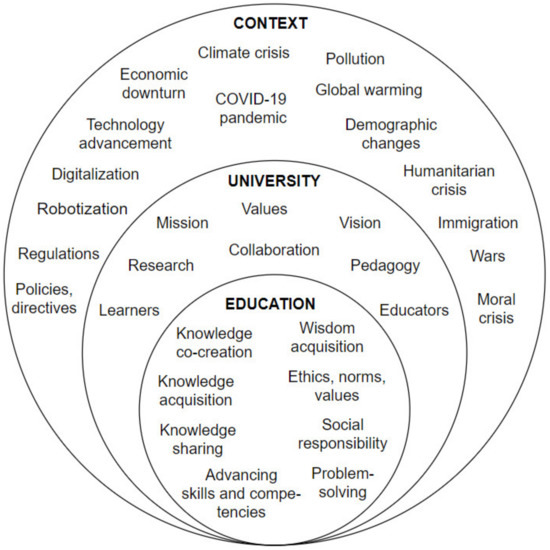

I strongly believe that universities and HE have a huge obligation in creating a better and wiser world. However, the context of university education is becoming more complex (Figure 1). Furthermore, the main dilemma ahead is how to integrate knowledge acquisition with wisdom acquisition. In order to solve businesses’ problems [34,35] and the wicked problems of our life [31], to manage complexity, we need to rethink what a university is (mission, vision, and values) and what a university needs to become [33]. In addition, we need to rethink what HE is and what it needs to become [30]. Therefore, this paper tackles an affirmative and significant phenomenon, i.e., how university education could facilitate the progress to a better and wiser world. More precisely, the issues are how to cultivate wisdom in HE, how to unite knowledge and wisdom acquisition when educating future generations for life, and how to prepare the next generation to solve complex problems, not only based on their knowledge but guided by their ethical and moral values. Figure 1 shows the complex context of HE that is the focus of this paper.

Figure 1.

Context of higher education.

My personal motivation in exploring this phenomenon is based on more than two decades of experience as an HE practitioner. This paper is inspired by my passion about learning, knowing, knowledge creation, knowledge sharing, and problem solving and by my deep care for students’ future in a wiser and better world. Therefore, the main research question of the paper is: how could university education facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world? The methodology involved case study research (CSR), including secondary research on fourteen Finnish universities’ missions, vision, and values, and online primary research asking HE participants and practitioners about what university and HE are and why and how they need to change.

The structure of this paper follows the five Ds (i.e., define, discover, dream, design, and destiny) of appreciative inquiry (AI), which is a constructive organizational design approach based on positive psychology. The paper has four sections. The introduction defined an affirmative phenomenon that is the focus of this paper, i.e., how universities and HE could facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world by integrating more wisdom inquiry into knowledge inquiry and learning. Furthermore, the concepts of wisdom and PW were presented, along with why PW is needed in HE and the complex context of this phenomenon (Figure 1). In Section 2, in accordance with the research questions, I explain why CSR is an appropriate research approach and I describe the data collection methods. Section 3 presents the case study and the findings of the secondary and primary, online, qualitative research. This includes three processes: (1) discovering evidence about the missions, visions, and values of fourteen Finnish universities of sciences and discovering the views of HE participants; (2) dreaming about what university education could or might be in the future; and (3) designing how universities and HE need to change. In the conclusion, the main research question is answered, and the outline of a possible destiny for HE, the implications for educators, the limitation of this research and an outline of the future along with educational research needs are provided. Finally, I assess the quality of the case study, highlight the novelty of its presentation, and point out the possible contributions of my research.

2. Research Methodology

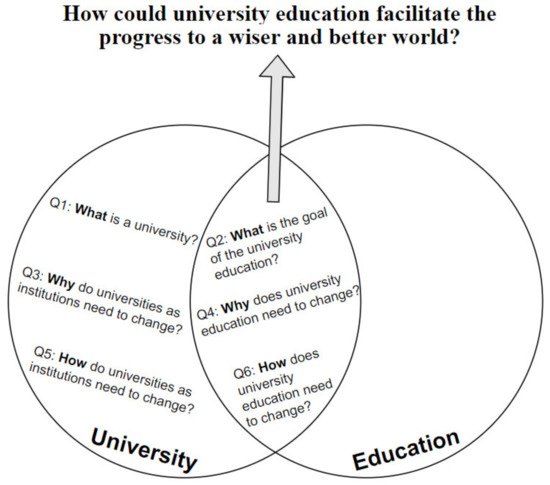

This paper focuses on HE as a research phenomenon (Figure 1). I seek to answer the main question: how could university education facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world? Here, I present the sub-questions, discuss the CSR methodology, and describe the data collection methods. The six sub-questions (Figure 2) are related to two themes: (1) the university as an institution and as a context (i.e., place and space) of HE; and (2) education as content, practice, and process.

Figure 2.

Research themes and questions.

My goal is to explore how HE could “educate for life not for school”, i.e., how university education (HE) could facilitate the progress to a wiser and better world. For this purpose, I selected the CSR methodology. This methodology is appropriate for my purpose because with CSR I am able to present real examples of the current state of HE in Finnish universities of sciences (USCs) and I am able to make contributions to the existing body of knowledge about HE.

The research questions are formulated as ”what”, ”why”, and ”how” questions (Figure 2). This concurs with Yin’s [36] (p. 8) definition of CSR as seeking to understand the why and the how of a real, current phenomenon. According to Myers, “the purpose of the case study research is to use empirical evidence from real people in real organizations to make an original contribution to knowledge” [37] (p. 73). There are four types of case study design [36] (pp. 46–60): single-holistic, single-embedded, multiple-holistic, and multiple-embedded. Stake [38] categorized case study types as: intrinsic—to better understand a specific case; instrumental—to provide generalization; and multiple or collective—to jointly research a phenomenon. The research approaches in CSR can be exploratory, explanatory, or descriptive.

For this paper I collected data from multiple sources through secondary and primary research to provide evidence from rich, multiple sources that demonstrates the complexity and reality of HE as a real-life and contemporary phenomenon. In the secondary research, I explored the mission, vision, and values of fourteen Finnish public USCs based on their official websites, and in the online research I asked HE participants (university students) and practitioners (university educators) to answer six research questions related to this paper (Figure 2). The link to the questions of the online inquiry on Google Jamboard was shared with over 200 LinkedIn connections (university students and educators), numerous ResearchGate researchers, two universities, students, and educators. The online platform was available for two months. Finally, I collected the anonymous answers, analyzed them with color coding, and identified emerging key words, and themes.

In brief, this paper presents a multiple-embedded, explorative, and descriptive case study. The goal is to demonstrate and better understand through examples what universities and HE are and why and how they need to change. Data were collected from secondary and primary sources.

3. The Case—Searching for Practical Wisdom in Higher Education

Here, I present the case and my findings from the secondary and primary, online, qualitative research. This section includes three processes: (1) logos—discovering, i.e., exploring the ”what” questions; (2) pathos—dreaming, i.e., bringing up arguments for the ”why” questions; and (3) ethos—designing, i.e., contemplating the answers to the ”how” questions.

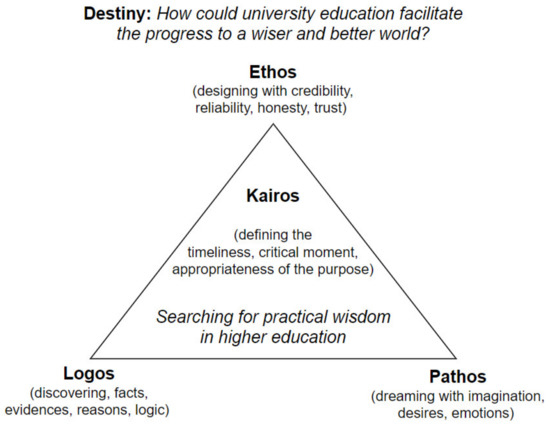

Aristotle argued that convincing argumentation and effective delivery of a message is based on ethos, pathos, and logos. Therefore, to present the case of “searching for wisdom in HE”, I will apply the elements of persuasive communication (Figure 3), namely kairos (i.e., purpose, appropriateness, timeliness, right, critical moment), logos (i.e., content, message, arguments, facts, evidence, logic, rationality), pathos (i.e., desire, imagination, feelings, emotions), and ethos (i.e., reliability, credibility, trust, positive feelings). The affirmative topic and its temporary character and critical timing were defined and discussed in the introduction (Figure 1). Here the focus is on logos, pathos, and ethos. Destiny will be presented in the conclusion.

Figure 3.

Framework for presenting the case.

3.1. Logos—Discovering What University and Higher Education Are

The purpose here is to explore what universities and HE are by focusing on the ”what” research questions (Figure 2, Q1 and Q2). In this phase the approach is with logos, discovering through rationality facts, evidence, and reasons for the existence of Finnish USCs. The research methodology involved secondary and primary research. Before presenting the findings, I discuss what universities and HE are.

“What is a university?” is an ontological question. First, based on a review of the literature, I present what being a university means and what philosophical concepts help us to understand universities. Next, after a brief introduction of the Finnish HE system, I present the findings based on research on the missions, visions, and values of fourteen Finnish public USCs (Table 1 and Table 2). Finally, I show the findings of my online survey about the views of HE participants and practitioners on what a university is and the goals of university education.

Table 1.

Keywords for missions, visions, and values of Finnish public universities.

Table 2.

Eight features of practical wisdom at Finnish USCs.

Barnett [39] asked very similar questions to this paper: “what is it to be a university? How might we understand the ‘being’ of a university?” [39] (pp. 59–60). He approached the understanding of universities with philosophical concepts of being, becoming, understanding, space (i.e., intellectual and discursive, epistemological, pedagogical and curricular, ontological space) and time, culture and anarchy, and authenticity and responsibility. Barnett discussed the metaphysical, scientific, entrepreneurial, and bureaucratic universities as being. Then, he classified research universities according to their possible epistemological positions, i.e., knowledge orientations, by applying two dimensions, namely knowledge-for-itself/knowledge-for-the-world (i.e., the interest structure at work) and knowledge-in-itself/knowledge-in-the-world (i.e., the location of knowledge production). Based on his framework, the university types identified were the ”ivory tower” university, the ”professional university”, the ”entrepreneurial university”, and the ”developmental university” [39] (pp. 31–32, Figure 2.1). The developmental university is the most relevant to this paper because its knowledge orientation is knowledge-for-the-world and knowledge-in-the-world. “This university is both active in the world and is generating knowledge through those activities in the world. It is intent on helping to improve the world—its knowledges are put to work for-the-world” [39] (pp. 31–32).

What is the goal of university education? According to Barnett, “it is the task of universities to help bring potential believers into valid knowing relationships with the world, wherever those potential believers may be in the world. … advancing public understanding in the world” [39] (p. 65, emphases original). He adds that “’understanding’ applies both to research and teaching. ‘Understanding’ is, therefore, a much larger concept than either research or teaching” [39] (p. 65). A university “endeavours to help the growth of understanding. Those endeavours may be direct efforts, in helping individuals or groups to advance their understandings; or they may be indirect efforts, putting ideas and knowledge into the public domain across the world to help in widening the conceptual resources and primary knowledge that might in turn further those individuals’ and groups’ understandings” [39] (p. 65).

Knowing and understanding develops through critical dialogue, which is another task of universities. New insights, new knowledge and knowing, emerge through critique, arguments and counter-arguments, debates, and dialogue. “The university in which such critical dialogue was not present would be no university” [39] (p. 31). Similarly to Barnett, Auxier [40] (pp. 247–255) sees the purpose of HE as lying in inspiring, motivating, encouraging, and supporting learners to explore, experience, and interpret the world and develop their own perceptions and judgments about the world.

However, there is a challenge for HE pedagogy: how learning can be fostered for an unknown future, for a complex, highly connected world that faces many global problems [31] (see Figure 1). Barnett argues that pedagogical challenges are not epistemological but ontological challenges. He proposes that “…the way forward lies in construing and enacting a pedagogy for human being. In other words, learning for an unknown future has to be a learning understood neither in terms of knowledge nor skills but of human qualities and dispositions. Learning for an unknown future calls, in short, for an ontological turn” [41] (p. 219). The task of HE pedagogy is enabling learners to flourish, to grow, to make effective and right interventions in the world. The educational tasks are: “first, bringing students to a sense that all descriptions of the world are contestable and, then, second, to a position of being able to prosper in such a world in which our categories even for understanding the situations in which we are placed, including understanding ourselves, are themselves contested” [41] (p. 225).

In brief, I have presented how a university as an institution and HE pedagogy are seen from a philosophical perspective. However, it is important to show how an organization is defined in the organizational studies and organizational psychology literature.

According to Haslam, the main characteristics of an organization are purpose; shared meaning, in the form of the interactions of roles, norms, and values; power; and status [42] (pp. 1–3). Furthermore, organizations are influenced by their environment and they influence their environment (see Figure 1). Morgan [43,44] (pp. 208–213) presented eight different metaphors of organizations: as machines, living organisms, brains, cultures, political systems, psychic prisons, flux and transformation, and as instruments of domination. Haslam [42] (pp. 3–13) described the four existing paradigms for studying organizations and their psychology as the economic, individual differences, human relations, and social cognition paradigms. He argues that there is a need for a social identity paradigm for studying organizations. Organizations could be studied at three levels, namely social-psychological (e.g., professional identities, values, sense making, meaning negotiation, learning), structural, and ecological (e.g., interactions, practices, relationships, networks, communities) levels [45] (p. 107). The human relations, social identity, and ecological level approaches to the study of universities as organizations are relevant to this paper.

I assume that an organization emerges through social interactions of people [34,35,46,47] and that it is a jointly constructed reality (i.e., the human relations paradigm). An organization is a complex, socially constructed system, not a static, solid thing or an objective or pre-given reality. Wenger [48] (pp. 241–262) distinguished two views of an organization: the designed organization (i.e., the institution or formal organization) and the constellation of practices (i.e., the living organization or informal organization). He argues that “the organization itself could be defined as the interaction of these two aspects” [48] (p. 241, emphasis added). An organization is constructed by people and therefore it can be viewed as the ”patterns of relating” [49] (p. 265) of humans interacting with each other in constructing the organization. Indeed, organizations are natural, evolving systems rather than formal, technically designed machines to achieve predetermined goals. People are the organization because they participate in it and they form it at the same time.

Defining the main characteristics of a university as an organization is important here because it confirms the research approach taken and explains why context, mission, vision, values, participants, and practitioners (see Figure 1) were selected to analyze Finnish USCs in this paper.

3.1.1. The Finnish Higher Education System

There are fourteen USCs in the HE system of Finland, of which ten are multidisciplinary and four are specialized universities. “A total of 13 universities and 22 universities of applied sciences operate in the Ministry of Education and Culture’s administrative branch” [50]. The fourteenth USC is the National Defense University, which operates under the defense administration. As of August 2005, both USCs and universities of applied sciences (UASs) provide master’s degrees. “Universities of sciences are multidisciplinary and regional higher education institutions with strong connections to business and industries as well as to regional development” [51] (p. 16). According to the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture, “to guarantee the freedom of science, the arts and higher education, universities are autonomous actors. Universities are independent legal entities that have the right to make independent decisions on matters related to their internal administration” [50].

3.1.2. Empirical Findings of the ”What” Questions

To study Finnish universities as organizations, I focused on their missions, visions, and values because these best indicate why they exist, what they want to achieve, and what values guide them. The findings of my secondary research are presented in Table 1.

Bachmann et al. [28] (p. 157) identified eight features of PW: it is action-oriented, integrative, normative, linked to sociality, related to pluralism, related to personality, related to cultural heritage, and related to limitation. Based on the descriptions of these eight characteristics of PW, I examined the Table 1 data and indicate the number of the university in Table 2 below. The findings show that the action-oriented feature of PW manifests itself in eleven universities, while the normative feature manifests in nine and sociality-linked characteristics in eight universities. There is only one university which shows all eight characteristics of PW.

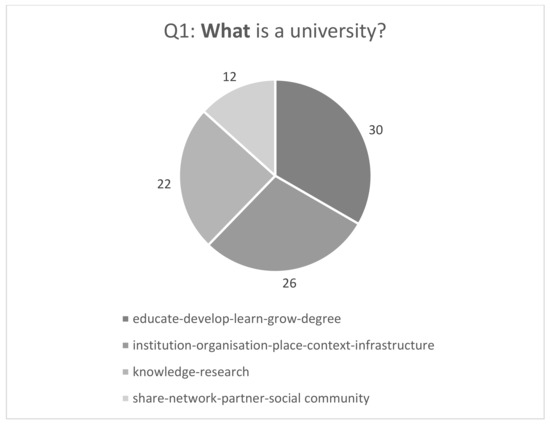

Next, based on primary data collected through my online research, I present the findings on how university practitioners and participants identified what a university is. These primary data could complement the secondary data in Table 1. In Figure 4, the findings of the online research show that the answers to what a university is formed four groups: (1) the roles of the university; (2) the university as a place, institution, and organization; (3) the university as a knowledge provider through research; and (4) the university as a partner, as part of the society. The following quotations are selected from the 24 responses received for Q1:

Figure 4.

Main characteristics of a university based on the primary research (numbers indicate the frequency of keywords in answers).

- Universities have three roles: educate the next generation (develop knowledge, skill, competence); do research and development in science; be a partner and contributor locally.

- A university is more than just an educational and research institution; it is a social community with special values.

- It is the basic starting place for education, motivation, and learning which, in an optimal case, are based on shared values and dreams. Here, students build their networks for life, they learn, grow and get inspired.

- A place for attaining academic and research skills for implementation of knowledge to serve the needs of the society and humanity. A place for personal growth into a responsible proactive citizen.

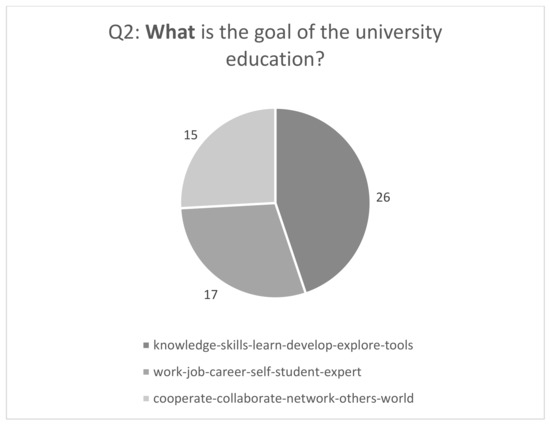

The findings for the question about the goals of university education (Q2) are presented in Figure 5. The goals of HE, according to the 17 answers from practitioners of and participants in HE, form three clusters (Figure 5): (1) providing knowledge, skills, and learning; (2) preparing students for the world of work; (3) cooperating and collaborating with others. These answers concur with the tasks of HE indicated by Barnett [39,41] and Auxier [40]. Furthermore, there are similarities between these answers and the Finnish Ministry of Education and Culture’s declaration: “the basic task of the universities is to engage in scientific research and provide the highest level of education based on it. Universities promote lifelong learning, interact with society and promote the societal impact of research results and artistic activities” [50]. Below are several selected responses to Q2:

Figure 5.

Three main goals of HE according to the primary research (numbers indicate the frequency of keywords in answers).

- The goal of university education is to give more understanding and bigger pictures about connections and real-life processes. It should promote wisdom and critical thinking.

- Teach the value of the knowledge and provide a toolset for self-management of the knowledge, including acquiring new knowledge.

- Higher education sets the basis for future jobs and job opportunities, it develops a broader understanding of context and inspires future leaders.

- To create a more civilized world through knowledge and competences and hence increase well-being in the world. Create better and sustainable solutions together with companies.

Summing up, in this part of the paper, the research findings based on the secondary (see Table 1 and Table 2) and primary (Figure 4 and Figure 5) data related to questions Q1—what is a university?—and Q2—what is the goal of university education?—were presented. A surprising finding was that all eight features of PW manifested themselves in the missions, visions, and values of the fourteen Finnish public USCs (see Table 2). Furthermore, the online research indicated that a university is not only an institution, a place, but also a social community with special values. The goal of HE is not only to provide knowledge, skills, and tools for students but, most importantly, to develop identities, inspire, and achieve societal impacts by applying knowledge to create a civilized world [41].

3.2. Pathos—Dreaming about the Future

In this section, I discuss why universities and HE need to change and then I present the findings of the primary research relating to the “why” questions (Figure 2, Q3 and Q4). This is the phase where responders dreamed with pathos, imagination, desire, emotion, and feeling about why universities as organizations and HE need to change.

Authors [33,39,40,41] have argued that universities as professional organizations and HE need to change. I concur with Weick and Barnett that universities, like any other organizations, are in fact in continuous change: they are in a process of evolving (cf. [52], p. 366) and becoming. Barnett argues that: “Being a university is always a matter of becoming a university. To put it cryptically, being a university is always unfinished business” [39] (p. 62). This process of becoming a university has empirical, ideological, imaginative, and value conditions [39] (pp. 60–62).

Therefore, the question is how universities can survive in the future, in an environment that is unstable, complex, and highly interconnected. Concurring with Maxwell [33], I strongly believe that traditional, bureaucratic universities should fundamentally change [30,53]; they need to become more proactive and innovative [54]. Universities as professional organizations need to become more organic, open, natural, and innovative organizations. Universities need to be both horizontally and vertically decentralized and employ highly skilled, highly trained, specialized professionals, experts working in creative project teams. Daft and Weick [55] (p. 288) call a proactive and innovative organization an enacting organization. These organizations take risks, are ready to experiment, undertake simulations and tests, and tend to ignore traditional norms and rules. Enacting organizations are created by their environment and, at the same time, create their own realities. They are involved in becoming and in interpretive sensemaking because they continuously discover and interpret the environment by acting with it, reacting to it, and enacting it. The external context of universities and HE is highly complex (see Figure 1), full of global problems and crises. Weick [56] (pp. 399–415) argues that enacted sensemaking in crisis situations is beneficial. “Enactment affects crisis management through several means such as the psychology of control, effects of action on stress levels, speed of interactions, and ideology” [56] (p. 411). Furthermore, taking the enactment perspective “urges people to include their own actions more prominently in the mental experiments they run to discover potential crises of which they may be the chief agents” [56] (p. 413). The question is whether we could today call universities enacting organizations.

According to previous studies from the literature, one reason why universities need to change is the increase of the influence of bureaucracy and power on the administrative staff. Bousquet argues that “the administration of higher education has changed considerably. Campus administrations have steadily diverged from the ideals of faculty governance, collegiality, and professional self-determination. Instead, they have embraced the values and practices of corporate management” [57] (p. 1). Similarly, Ginsberg [58] claims that the bureaucracy at schools and universities has been growing steadily and it reduces the power of faculty to influence the future of the university. “The existence of large numbers of deanlets gives ambitious senior administrators the tools with which to manage the university with minimal faculty involvement and to impose their own programs and priorities on the campus” [58] (p. 206, emphasis added). Ginsberg suggests “trimming administrative fat” and reducing the size of bureaucracy. He recommends “that boards truly concerned with maintaining the quality of their schools compel university administrators to shift spending priorities from management into the real business of the university—teaching and research” [58] (p. 205).

One main role of universities is education (see Figure 4). The future success of a society depends on both science and education. The physicist Kaku anticipates four trends in the future: (1) science will continue to be the engine of prosperity; (2) the economy will shift from commodity capitalism to intellectual capitalism; (3) the job market will favor non-repetitive workers; and (4) education will be absolutely essential [59]. Kaku argues that products of the mind cannot be mass produced; creativity and artistic skills will be valued and demand for intellectual workers with specialized skillsets in construction, design, and computing will increase. Regarding academia and HE, Kaku calls for more focus on developing students’ high-level skills, emphasizing scientific education, and embracing new technology. However, in my view, Kaku’s high emphasis on developing skills contradicts Barnett’s view on the role of education in a supercomplex world. Barnett distinguishes two forms of uncertainty and argues that learners need to cope with the uncertainty of the environment (information overload, unpredictability in environmental response) and with personal uncertainty (anxiety, fragility, chaos) [41] (p. 222). He points out that education has a primarily ontological and not epistemological task, i.e., enabling individuals to prosper [41] (p. 224), because “one goes forward not because one has either knowledge or skills but because one has a self that is adequate to such an uncertain world” [41] (p. 227). Auxier [40] (pp. 247–255) argues for changes in HE. In his view, the idea of having a physical campus, the level of academic freedom, the role of professors as transmitters of knowledge, the traditional ways of learning and lecturing, evaluation criteria, and old-fashioned tests need to change. Maxwell does not deny the need for knowledge inquiry and scientific education; however, he expresses the need for wisdom in HE and writes that “as an urgent matter, we need to put wisdom-inquiry into practice in schools and universities around the world. We need a change of paradigm, an academic revolution. … We urgently need a high-profile campaign to bring wisdom-inquiry to our universities” [60] (p. 130, emphases added).

Empirical Findings of “Why” Questions

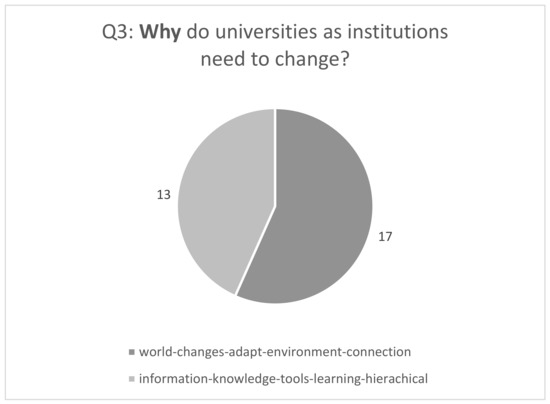

The findings of my primary research regarding the question about why universities as institutions need to change (Q3) are presented in Figure 6. There were 11 answers to Q3. The arguments clearly indicated external and internal factors of change, for example:

Figure 6.

External and internal drivers of change based on the primary research (numbers indicate the frequency of keywords in answers).

- Because the world changes, and the learning tools change and develop. The university should nonetheless be true to science. For example, the university must not be affected by pressures from ‘political correctness’.

- Because the rest of the world is changing too (i.e., climate change, politics, gender equality, LGBTQ).

- Those universities that have a strong hierarchical system should change and they need to be more flexible and resilient.

- If they have a strong hierarchical system, they cannot adapt to the fast-changing environment as quickly as necessary, cannot take the opportunities, do not give enough space for new ideas.

The 15 answers to the question about why university education needs to change (Q4) clearly indicate that HE needs to change because of the changes in the world (see Figure 1) and in the world of work. Respondents’ arguments were that HE needs to become up-to-date in a context where there are fast and rapid changes in the world, notably environmental changes, and where digitalization and new technology have changed the world of work. Higher education needs to help society to drive changes; it needs to provide solutions to problems in the world. Furthermore, the HE changes are driven by needs for different competencies and skills, continuous learning, emotional intelligence, intuitiveness, flexibility, creativity, teamwork, new and advanced knowledge, argumentation, and new ways of communication. Importantly, the answers highlighted that there are needs for quality pedagogy, changes in outdated pedagogical approaches, new criteria for teachers, different learning tools, new approaches to learning, and for a reassessment of the costs and benefits of a university degree. A few selected answers to Q4 are presented below:

- The world changes, companies develop, and universities need to keep up to date—they should be ahead of things, providing top knowledge and solutions to the world.

- The complex world needs different skills than before, emotional and intuitive intelligence are at the core of successful teamwork. Teamwork is at the core of all work.

- Because the way we work has also changed. The pace is much faster and digital. Creativity plays also a much bigger role.

- Too many unhappy people are out there: students, employers, parents, professors...There are a lot of places for self-criticism. Maybe the criteria for teachers are outdated, the number of publications does not guarantee quality pedagogy.

In brief, the findings concerning the ”why” questions (Figure 2, Q3 and Q4) were presented in this section. Next, the focus is on the ”how” questions.

3.3. Ethos—Designing How to Change

In this section, I present the findings of the primary research for the ”how” questions (Figure 2, Q5 and Q6). This is the phase of ethos, where responders designed, with credibility, reliability, character, integrity, credibility, trustworthiness, honesty, and trust, how universities as organizations and HE need to change.

In the literature, I found an idea presented by Vasconcelos [61] to be relevant to this research. Vasconcelos argues that building wisdom capital (WC) “may help individuals and organizations to keep the right path … to contribute to something greater than themselves through their potentialities, skills and capabilities.” His two-level model of WC demonstrates how individuals and organizations could contribute to building WC. According to him, on the one hand, individual WC (i.e., wise people) aims to do good, do right, achieve excellence, improve society, and serve others and themselves by engaging in meaningful projects and challenges. On the other hand, organizational WC (i.e., wise organizations) aims to create a greater common and human good and to create well-being. It raises the question whether building the WC of universities and HE practitioners could be the way to build a better and wiser world.

Empirical Findings of “How” Questions

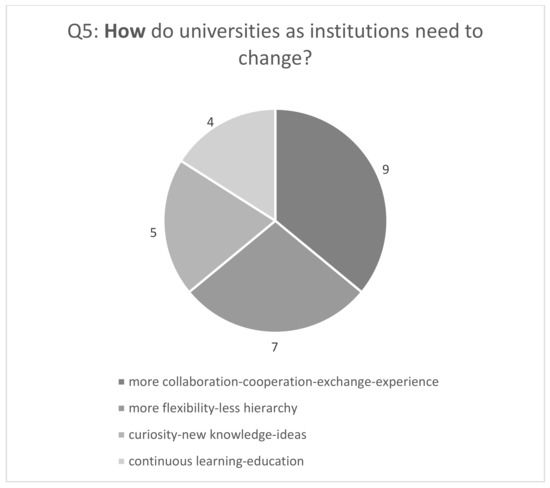

There were 22 responses to Q5. I illustrate the findings with selected answers below and with Figure 7:

Figure 7.

Directions of needed university changes based on the primary research (numbers indicate the frequency of keywords in answers).

- Universities need to be more open to collaboration with the other role players in the business and social environment.

- They should be more flexible: if they have a strong hierarchical system, they cannot adapt to the fast-changing environment as quickly as necessary, cannot take the opportunities, do not give enough space for new ideas; They should optimize their processes.

- Stop thinking traditionally and increase collaboration with other institutions—grow together to a real ecosystem. Decrease hierarchy and appreciate talents in all educational levels (not just doctors).

- Open up! More international cooperation. The employer/employee market is global. More exchange of the teaching staff as well as of students.

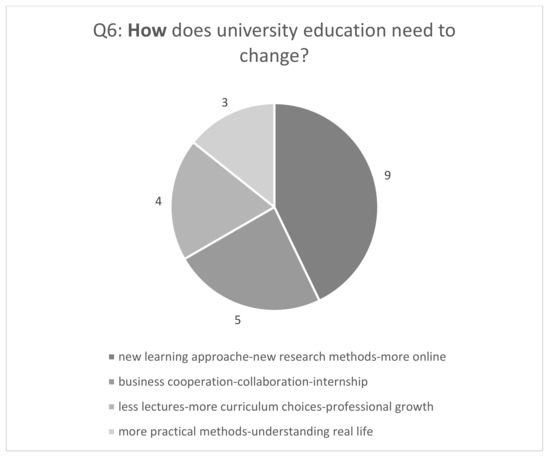

Samples from 14 responses to the question about how university education needs to change (see Figure 8) are given below:

Figure 8.

Directions of needed university education changes based on the primary research (numbers indicate the frequency of keywords in answers).

- It should change a lot in many areas (e.g., collaboration, using new technologies, new educational and research methods, adaptability, openness, etc.).

- By encouraging the use of new and different research methods and by spreading seeds of curiosity and willingness to challenge current facts.

- Fewer lectures and more practical assignments. Also, cooperate with companies and institutions to produce knowledge.

- There is too much theoretical knowledge and too little real understanding about life and society. Studying is too slow and unambitious. Students are not committed to getting ready for greater purposes. There are a lot of complaints as to the enthusiasm and devotion of the teaching staff.

In summary, this case study sought to answer three types of research questions, ”what”, ”why”, and ”how” questions (see Figure 2), by exploring and describing the characteristics of universities and HE. The research methodology involved a case study. The findings of the research based on the secondary data showed that all eight features of PW were present (see Table 2) in the fourteen Finnish public universities (see Table 1). Furthermore, the findings of the online research based on primary data complemented the case study with rich data (see Figure 4, Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7 and Figure 8). In the following section, I will suggest more specific steps for universities and HE.

4. Conclusions—Destiny

In this last section of the paper, first, I answer the main research question. Then, I present the implications for educators, indicate the limitations of this case study, and propose future educational research areas. Next, as additional research opportunities based on topics in the literature, I discuss the ideas about “the university of the future and the future of the university”. Finally, I assess the quality of the case study, highlight the novelty of its presentation, and point out the possible contributions of my research.

4.1. Answering the Main Research Question

This case involved searching for PW in HE with logos, pathos, and ethos (see Figure 3) and with the aim of finding answers to the main question: how could university education facilitate progress to a wiser and better world? For this purpose, six questions were proposed (see Figure 2), the findings of the research based on secondary and primary data were presented, the missions, visions, and values of fourteen Finnish public USCs were explored, along with the eight features [28] of PW practices (see Table 1 and Table 2), and the answers of HE practitioners were analyzed and presented.

In his numerous publications, Maxwell [12,32,33,60] claims that to build a civilized world we would need to integrate wisdom and science and “that requires that we bring about a radical transformation in universities all over the world. At present universities are devoted to the pursuit of specialized knowledge and technology. However, they need to be transformed so that the basic task becomes to help humanity tackle problems of living, including global problems, in increasingly cooperatively rational ways” [32] (Preface). How academia could be revolutionized, transformed, and changed is an urgent challenge that has been investigated by Barnett [39,41], Auxier [40], and other educational researchers.

I argue that the literature on management could help in designing the process of change process for universities. In the literature on management, there are numerous studies on change management, the forces of change, types of change, the process of change, the conditions of successful change, and so on. The eight phases of change (e.g., [62,63,64,65]), the transformation of an organization through reframing, restructuring, revitalization, and renewal (e.g., [66] (pp. 6–8)), episodic and continuous change (e.g., [52]), and dealing with change (e.g., [67]) are relevant to designing changes for universities and HE. However, here I focus only on the process and the phases of change as described in a few selected sources.

My goal is to relate the eight-stage process of change (see [62] (p. 21) and [63] (p. 7)) in order to design changes for universities and HE and facilitate progress to a wiser and better world for all.

- Establishing a sense of urgency—The complex, highly interconnected environment of universities and education (Figure 1), involving global crises and problems of the world that need wise solutions [31,32], are external indicators of the need for urgency. However, there are internal urgencies as well. Bousquet [57] and Ginsberg [58] worry about the low influence of faculty on the future of the university and they are concerned about the growth of bureaucracy at universities. Ginsberg provides specific recommendations “to board members, the media, faculty members, alumni, students and parents, and, lastly, administrators themselves” that include “trimming administrative fat” [58] (p. 206). Furthermore, an attitude involving too much reliance on knowledge inquiry could lead to overconfidence in knowledge, and it could diminish attitudes of wisdom [13].

- Creating the guiding coalition—Universities are living organisms formed by interactions of people [46,48,49]. If universities want to contribute to creating a wiser and better world and to solving global problems, they need to become enacting and open organizations [55,56]. To form a team, a coalition that understands the urgency and is capable of leading the change, it is necessary that university practitioners, educators, students, and leaders closely network and collaborate with businesses, influencers, and politicians.

- Developing a vision and strategy—Universities have missions, visions, values, and strategies that are announced on their websites (e.g., [50,68] and see Table 1). The problem could be that these nicely formulated visions and strategies are not enacted, not put into practice, or not implemented in the intended ways. Developing universities’ visions and strategies for change should be a bottom-up, participative, and collaborative approach in order to gain commitment from all participants who will implement them. If they are formulated only by the administration, then they could show a very rosy picture about the university, they might not reflect the reality, and they might not address the problems that need urgent solutions.

- Communicating the vision and strategies of change—There needs to be broad, multichannel, continuous communication with simple and consistent messages underlining the urgency of change, the societal impacts at stake, the importance of ethical and moral values, the need for wisdom inquiry as well as knowledge inquiry, and the need for PW in HE.

- Empowering broad-based action—The change should not destroy what is good and working at universities and in HE; rather, it needs to find and eliminate the existing obstacles to realizing the vision of change. For instance, appreciative inquiry could be applied for organization development, focusing on existing strengths and reinforcing the life-giving forces of the university [47].

- Generating short-term wins—In their change strategies, universities could have milestones to celebrate, reward, and communicate their achievements together with their stakeholders. This would generate a sense of progress toward the vision and it would motivate and energize participants. Small wins could simplify the crises, help sensemaking through actions, and motivate people to take the role of active agents of change [56].

- Consolidating gains and producing more change—Using ethos, credibility, trust, honesty, reliability, and character help to continue the change process. Supporting university staff, students, faculty members, educators, and partners with training, involving them in meaningful projects, and asking them to initiate new projects that would support the vision of change would all be useful. The societal impacts of universities and HE could be fostered by solving real-life business problems (cf. [34,35,53]) and developing business organizations.

- Anchoring new approaches in the culture—It is important to train university practitioners to become wise leaders [18], intelligent workers, wisdom workers [69], and phronetic leaders [21] of the 21st century. In the conceptual age, not only knowledge rules but wisdom and PW guide actions [12,41,70]. Furthermore, it is vital to build individual and organizational wisdom capital [61] by strengthening HE practitioners’ knowledge, skills, expertise, capabilities, and ethical orientation and by encouraging PW in universities’ strategies, policies, teaching, research, relationships, and decision making.

4.2. Implications for Educators

Educators have a key role in creating the future. I concur with Pink [70] (pp. 49–50) who argues that in the 21st century we are entering a new age, the ”conceptual age”, where instead of knowledge workers we will need creators, empathizers, pattern recognizers, and meaning makers. In the conceptual age we will need a different thinking and a new approach to life; specifically, we will need ”high concept” and “high touch”.

“High concept involves the capacity to detect patterns and opportunities, to create artistic and emotional beauty, to craft a satisfying narrative, and to combine seemingly unrelated ideas into something new. High touch involves the ability to empathize with others, to understand the subtleties of human interaction, to find joy in one’s self and to elicit it in others, and to stretch beyond the quotidian in pursuit of purpose and meaning” [70] (pp. 2–3, emphases added).

Pink clearly describes the knowledge, skills, and competences we will need in the 21st century to create a better, wiser, and a meaningful world. I argue that these should be the main missions, visions, and values of universities too. To achieve this we would need educators to become “wisdom workers”, intelligent workers, instead of being just knowledge workers [69]. Bousquet [57] starts his book with a quotation from Albert Einstein (1949) about the importance of intellectual workers: “An organization of intellectual workers can have the greatest significance for society as a whole by influencing public opinion through publicity and education. Indeed, it is its proper task to defend academic freedom, without which a healthy development of democracy is impossible” [57].

Educators should become ”wise leaders” who: (1) use reason and careful observations; (2) allow for non-rational and subjective elements when making decisions; (3) value humane and virtuous outcomes; (4) have practical actions oriented towards everyday life, including work, and (5) are articulate, understand the aesthetic dimension of their work, and seek the intrinsic personal and social rewards of contributing to a good life [18] (pp. 178–180). Similarly, Nonaka and Takeuchi [21] argue for the need for phronetic leadership, i.e., leadership guided by practical wisdom. According to them, wise leaders can (1) judge goodness, (2) grasp the essence of matters, (3) create shared contexts, (4) communicate the essence of matters, (5) exercise political power, and (6) foster practical wisdom in others. I suggest that universities with phronetic leadership—that is, education with educators as ”wisdom workers” and ”wise leaders”—will be able to facilitate progress to a wiser and better world and only then will wisdom, practical wisdom, be cultivated in the feelings, minds, and actions of future generations [29,53].

4.3. Limitations and Further Educational Research

This case study focused on fourteen public universities of the Finnish HE system [50,68] (see Table 1 and Table 2). Therefore, an international comparison would provide a new area of research to complement the findings of this case. As the data about the Finnish USCs were collected through secondary research, it would be useful to conduct interviews with university practitioners, educators, students, and partners (organizations) to validate the findings of the case study. In addition, it would be useful to explore whether and how the eight characteristics of PW (see Table 2) manifest themselves in the strategies, projects, curricula, and pedagogy of universities.

It is natural that HE focuses on performance, success, function, argumentation, specialization, logic, and seriousness, and on accumulating knowledge and developing skills and competencies. However, to create a meaningful, wise, and better world for humanity, we need more than these. According to Barnett, “there is the educational task of preparing students for a complex world, for a world in which incomplete judgements or decisions have to be made; incomplete either because of the press of time or because insufficient evidence is to hand fully to warrant any particular decision or because the outcomes are unpredictable” [41] (p. 223). Concurring with Pink, I believe that, in the 21st century, we will need to enhance six senses: “Design. Story. Symphony. Empathy. Play. Meaning. These six senses increasingly will guide our lives and shape our world. … These abilities have always comprised part of what it means to be human” [70] (p. 67). Educational research could focus on exploring how these six senses, together with PW, could be cultivated at universities. Furthermore, research could look at what changes would be required in the curricula, pedagogy, leadership, collaborations, missions, visions, values, and organizational structures of universities.

Furthermore, Hussey and Smith [71] provide a critique of HE in the UK and indicate several problems: “chronic under-funding, the replacement of student grants with loans and the introduction of tuition fees; the growth of managerialism; the emphasis on accountability and decline of trust; the growth of a competitive, market ethos; modular degrees, knowledge treated as a commodity and students seen as customers; the drift towards a two-tiered system, with teaching colleges and research universities; and casualization of the academic profession” [71] (pp. 1–7). Similar to Auxier [40], Hussey and Smith also suggest several educational research areas, such as: “ways of managing universities; proper inspection; better ways of organizing students’ learning; improving teaching and learning; better approaches to assessment, and the proper use of ideas such as learning outcomes” [71] (pp. 129–135). As a vast research area, the future of the university is discussed next.

4.4. The University of the Future and the Future of the University As Research Areas

The ”university of the future” offers vast opportunities for researchers. If we concur with Barnett that “Being a university is always a matter of becoming a university” [39] (p. 62), then exploring the features of the future university and its process of becoming can offer rich opportunities for researchers. Barnett outlines four conditions of a university’s being, specifically empirical, ideological, imaginative, and value conditions [39] (pp. 60–62). These conditions could be researched based on the questions Barnett contemplates:

- Empirical conditions—“What is the extent of its funding? To what degree can it raise additional income? How is it perceived in the world—or even by its own students and its own staff?”;

- Ideological conditions—“What is the dominant sense of a university in this society? To what degree is it expected to be entrepreneurial? To what degree is it expected to ‘serve’ society?”;

- Imaginative conditions—“What are the visions that the university entertains for itself? What are the possibilities that it imagines for itself … its own ‘imaginaries’? Are those imaginative possibilities merely an extension of what it has been and is now; or is a quite different future envisaged for it?”;

- Value conditions—“Is a university mainly concerned to live within itself, a university in-itself (the research university); or to profit from the world—a university for-itself (the entrepreneurial university); or to attend to the wider society—a university for-the-Other? Does it believe that inquiry as such is valuable, is its ‘own end’ … or does it believe that inquiry is only valuable insofar as it is demonstrably put to use in the world, or can it identify a new relationship for itself with the world?” [39] (pp. 60–62).

This paper sought to contribute to the value conditions of being and becoming a university through the search for practical wisdom in HE. Researchers should be encouraged to explore the characteristics of the possible forms of the future university, such as liquid, therapeutic, authentic, and ecological universities (see [39] (pp. 109–151), [72] (pp. 62–73), and [73] (pp. 74–90)).

The imaginary concepts of the university, however, need to satisfy five criteria of adequacy as follows: range, depth, feasibility, ethics, and emergence [72] (p. 71). Researching these criteria and testing an imaginary future form of the university is another interesting research area. The emerging ecological university [73] (pp. 87–89) of the 21st century could be both authentic (inward pointing) and responsible (outward pointing). “This is a university that takes seriously both the world’s interconnectedness and the university’s interconnectedness with the world. … This is a university neither in-itself (the research university) nor for-itself (the entrepreneurial university) but for-others” [73] (pp. 87–88). This paper contributes to the concept of the ecological university through the search for answers to the question: how could university education facilitate progress to a wiser and better world? Further exploring the concept of the ecological university is another exciting research topic. The idea of the ecological university is important, especially now when the world faces several global challenges [31]: “disease, illiteracy and unduly limited education, climate change, dire poverty, lack of capability and basic resource, misunderstandings across communities, excessive use of the earth’s resources, energy depletion and so on and so on—requires the coming of the ecological university” [73] (p. 89).

Researchers (e.g., Rothblatt, Morley, Standaert, and Nixon [74,75,76,77]) are actively searching for ideas and possibilities for the future university. Rothblatt argues that “the multiversity of the twenty-first century, by definition, is a house of many mansions. No single idea prevails, but many exist” [74] (p. 24). Morley has set up a research agenda for the university of the future and argues that gender, academic values and standards, environmental sustainability, critical knowledge, and opportunity and wealth distribution topics will need to be addressed [75] (pp. 26–35). Standaert argues that the network society brings a fundamental paradigm shift in HE [76] by shifting learning from place to space. He argues that “universities in the future will not only be places of knowledge “production” or of “virtual communication” but also spaces of encounters. One challenge for networked universities is to become in new ways such privileged spaces of encounters. This supposes an ethos of a renewed attention to “in-betweenness,” to concrete places where the actors (teachers, students, researchers) encounter each other by treating each other as subjects” [76] (p. 93). This paradigm shift from place to space and its consequences for the networked university are fascinating research areas too. Nixon worries about the responsibilities of universities: “Universities of the future will continue to have multiple responsibilities and academics will continue to be involved in a wide variety of practices relating to research, teaching and scholarship. Central to those responsibilities and practices, however, will be a commitment to providing all students with a space within which to develop capabilities necessary to flourish as receptive and critical learners” [77] (p. 147). “Universities of the future, then, have a vital part to play not only in sustaining and developing modes of practical reasoning or deliberation, but in ensuring that these are not distorted through the imposition of wholly inappropriate bureaucratic requirements” [77] (p. 148). Therefore, future research could focus on areas such as modes of reasoning (phronesis), the role of future universities in sustaining and developing modes of practical reasoning or deliberation, and universities’ commitment to the common good.

There are also research areas relating to philosophical proposals for the “future of the university” and HE (e.g., Stoller and Kramer, Allan, and Barnett [78,79,80], as well as Auxier [40]). Stoller and Kramer focus on the philosophy of HE and develop its future directions as follows [78] (pp. 15–18, emphases original):

- “A philosophy must view higher education as an institutional type, accounting both for its distinctive elements and its organizational complexities.”

- “A philosophy of higher education must build on the complex network of actors and cultures in the system.”

- “A philosophy of higher education advances a cohesive and critical imaginary for higher education in relationship to various, social, political, economic, and ethical contexts and concerns.”

- “A philosophy of higher education must develop a robust account of teaching, learning, and knowing.”

- “A philosophy of higher education must advance a theoretical discourse that appropriately denotes its practices and its aims.”

Stoller and Kramer’s guidelines for philosophy as a discipline and as a practice offer new educational research opportunities. Allan [79] discusses education and training and argues that “Educating students, as opposed to only training them, is creating conditions that make it possible for them to learn how to become both effective leaders and good citizens” [79] (p. 112). Allan’s arguments support the message of this paper because they emphasize the need for practical wisdom (i.e., phronesis, good sense) in educational practices: “Wisdom and skilfulness are prudential practices since they provide advisories on how best to gain verified knowledge or to create valuable objects, whereas good sense is a practice advising persons on how best to interact with others in determining and affecting those or any other purposes” [79] (p. 112). Allan is correct in saying that “Practices, both prudential and moral, can be learned but they cannot be taught. They are not information to be found in books or on the internet or noted down during a lecture. They are not instructions to be followed or hypotheses to test” [79] (p. 112). Future research could explore the role of educators in developing effective leaders and good citizens. Barnett defines culture as “a supremely value-laden human achievement. It is a way of sustaining society through those symbols and meanings and activities to which is attached the highest value” [80] (p. 136). He argues that “such a value-laden and value-oriented function for the university has now been put in question and even been extinguished” [80] (p. 136). Therefore, it would be important to research the idea of culture as the essence of the ecological university, culture as an ecosystem (i.e., the cultural ecosystem, ecological culture), and explore how “the different manifestations of culture, in particular the (a) cognitive, (b) practical, (c) communicative, (d) expressive and (e) material domains” [80] (p. 140) express themselves in the context of the university.

To sum up, this paper, along with the literature on educational research and its philosophy, can provide novel research opportunities for HE researchers for many decades to come.

4.5. Quality, Novelty, and Contributions

In this research paper, I presented an explorative and descriptive case study. According to Myers [37] (pp. 82–85), the quality of a case study in general can be assessed based on six criteria: (1) it must be considered “interesting”; (2) it must display sufficient evidence; (3) it should be in some way ”complete”; (4) it must consider alternative perspectives; (5) it should be written in an engaging manner; (6) it should somehow contribute to knowledge [37] (p. 83).

Drawing on Myers’ work, I conclude that the case study presented in this paper met the six quality criteria in the following ways (1) it was not only “interesting” to university educators and leaders but, with its contemporary character, provides insights for university students and business partners as well; (2) it was based on multiple sources (i.e., books, articles, online sources) and on secondary (see Table 1) and primary (Google Jamboard) data as evidence; (3) it was ”complete”, as it used all relevant and current data available, i.e., the data about the fourteen Finnish public USCs; (4) it has implications for educators and outlined future research possibilities; (5) it was written in a clear, simple, and logical way, and it deployed an effective communication framework (see Figure 3) as a creative guiding principle for communication; and (6) it contributes to knowledge and to a better understanding of the role of wisdom, specifically PW, in HE.

The quality of a case study depends on its objectivity and generalizability as well. It could be difficult to generalize this case study because the secondary data (Table 1) represent Finnish USCs. I admit that using multiple sources in CSR is both an advantage and disadvantage at the same time. It is beneficial because it shows the complexity of the situation but the abundance of data and documents can cause difficulties when trying to focus on essentials and when trying to clearly present the case. I concur with Gray [81] (pp. 273–274) that the large volumes of data can make writing case study reports difficult. He suggests that the case study report should have a clear “chain of evidence” referring to the documents when arguing and making conclusions. This increases case study reliability. However, it requires that the researcher consistently follow this practice and conduct the CSR in a very disciplined, rigorous way. I created a communication framework (see Figure 3) as a “chain of evidence” to present this case. This framework helped me to focus on the essentials and it strongly supported the logic involved in presenting the case.

The novelty of the case study was in the application of an effective communication framework (see Figure 3). My objective was to provide readers with a clear structure and a logical flow for the case study through steps that involved deciding on an affirmative and contemporary topic (kairos) (Figure 1 and Figure 2); discovering and presenting facts, evidence, and reasons (logos) (Table 1 and Table 2); dreaming with imagination, desire, and emotion (pathos); and designing with credibility, reliability, and trust (ethos), and then concluding by addressing the intentions (destiny) of the case study.

With this case study research, I sought to contribute to a better understanding of the ”practical wisdom in HE” phenomenon. I argued that HE needs to consider all three psychological dimensions of wisdom, i.e., the affective (e.g., sympathy and compassion for others), reflective (e.g., overcoming subjectivity and reducing ego-centeredness), and cognitive (e.g., seeing reality and understanding truth) dimensions. In a complex and highly connected world, it is not enough to foster only knowledge inquiry in education. There is an urgent need for wisdom inquiry in HE. When educators become wise leaders, phronetic leaders, they will cultivate not only the wisdom of knowledge, but the wisdom of practice and the wisdom of life in future generations. Only then will we achieve a better and wiser world. I hope that this case study inspires actors in HE and draws their attention to wisdom, specifically practical wisdom, in their everyday practices. I admit that this contribution is only a small step toward solving the wicked and complex problems of our lives, but it is a necessary step toward a wiser and better world for all.

Funding

There was no external funding provided for this research.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Participation in the primary online research has been entirely voluntary and by clicking the provided link participants gave their consent to participate in this research. Data were anonymously analysed and cannot be linked to individuals in any way.

Data Availability Statement

Secondary data are available freely on the websites of the fourteen public Finnish universities of sciences (Appendix A). Answers to the research questions were collected through a primary online inquiry where participation was voluntary and contributions were anonymous. The author declares that participants cannot be identified in any way. Data are available upon request.

Acknowledgments

I acknowledge with appreciation the contributions of the anonymous practitioners, university students, staff, and colleagues to the online survey. I thank Gerard Danford for proofreading my paper.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Appendix A. Links to University Websites (According to Table 1)

- University of Helsinki, https://www.helsinki.fi/en/about-us/basic-information (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Åbo Akademi University, https://www.abo.fi/en/about-abo-akademi-university/ (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Turku, https://www.utu.fi/en/university/university-strategy-2030 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Jyväskylä, https://www.jyu.fi/en/university/strategy-2030 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Oulu, Strategy of the University of Oulu | University of Oulu, https://www.oulu.fi/en/university-values (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Vaasa, https://www.uwasa.fi/en/university/strategy-and-values (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Lapland, https://www.ulapland.fi/EN/About-us/Strategy (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of Eastern Finland, https://www.uef.fi/en/strategy-2030 (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Aalto University, https://act.aalto.fi/en/strategy, https://act.aalto.fi/en/our-strategy/our-purpose-values-and-way-of-working (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Tampere University, https://www.tuni.fi/en/about-us/tampere-university/strategy-and-key-information?navref=liftup-links-link (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Hanken School of Economics, https://www.hanken.fi/en/about-hanken/hanken/mission-and-vision, https://www.hanken.fi/en/about-hanken/hanken/strategies (accessed on 4 June 2021), https://www.hanken.fi/system/files/2021-01/hanken_in_a_nutshell_2020_eng_0.pdf (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- Lappenranta-Lahti University of Technology (LUT), https://www.lut.fi/web/en/get-to-know-us/introducing-the-university/strategy (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- National Defense University, https://www.ndu.edu/About/Vision-Mission/ (accessed on 4 June 2021).

- University of the Arts of Helsinki, https://www.uniarts.fi/en/general-info/vision-mission-and-values/ (accessed on 4 June 2021).

References

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Available online: https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/wisdom (accessed on 23 April 2021).

- Clayton, V. Erikson’s theory of human development as it applies to the aged: Wisdom as contradictory cognition. Hum. Dev. 1975, 18, 119–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sternberg, R.J. Implicit Theories of Intelligence, Creativity, and Wisdom. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1985, 49, 607–627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Robinson, D.N. Wisdom through the ages. In Wisdom: Its Nature, Origins, and Development; Sternberg, R.J., Ed.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Baltes, P.B. The aging mind: Potential and limits. Gerontologist 1993, 33, 580–594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baltes, P.B.; Staudinger, U. Wisdom: A metaheuristic (pragmatic) to orchestrate mind and virtue toward excellence. Am. Psychol. 2000, 55, 122–136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeste, D.V.; Ardelt, M.; Blazer, D.; Kraemer, H.C.; Vaillant, G.; Meeks, T.W. Expert consensus on characteristics of wisdom: A Delphi method study. Gerontologist 2010, 50, 668–680. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Bangen, K.J.; Meeks, T.W.; Jeste, D.V. Defining and assessing wisdom: A review of the literature. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatry 2013, 21, 1254–1266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Ardelt, M. Wisdom as expert knowledge system: A critical review of a contemporary operationalization of an ancient concept. Hum. Dev. 2004, 47, 257–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Glück, J.; Bischof, B.; Siebenhüner, L. Knows what is good and bad. Can teach you things. Does lots of crosswords: Children’s knowledge about wisdom. Eur. J. Dev. Psychol. 2012, 9, 582–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sternberg, R.J. Intelligence in its cultural context. In Advances in Culture and Psychology; Gelfand, M.J., Ciu, C., Hong, Y., Eds.; Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2012; pp. 205–248. [Google Scholar]

- Maxwell, N. From Knowledge to Wisdom; Blackwell: Oxford, UK, 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Weick, K.E. Chapter 16: The attitude of wisdom: Ambivalence as the optimal compromise. In Making Sense of the Organization; Weick, K.E., Ed.; Blackwell Publishing Ltd.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2004; pp. 361–379. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B.; Rooney, D. Wisdom Management: Tension between Theory and Practice in Practice. 2005. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/37618441_Wisdom_Management_Tensions_Between_Theory_And_Practice_In_Practice (accessed on 10 May 2021).

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R. A firm as a dialectic being: Towards a dynamic theory of a firm. Ind. Corp. Chang. 2002, 11, 995–1009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R. Strategic management as distributed practical wisdom (phronesis). Ind. Corp. Chang. 2007, 16, 371–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nonaka, I.; Toyama, R.; Hirata, T. Managing Flow. A Process. Theory of the Knowledge-Based Firm; Palgrave Macmillan: New York, NY, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- McKenna, B.; Rooney, D.; Boal, K.B. Wisdom principles as a meta-theoretical basis for evaluating leadership. Leadersh. Q. 2009, 20, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dobson, J. From a Knowledge Economy to a Wisdom Economy. 2010. Available online: https://www.thersa.org/discover/publications-and-articles/rsa-comment/2010/03/from-a-knowledge-economy-to-a-wisdom-economy (accessed on 22 April 2021).

- Rooney, D.; McKenna, B.; Liesch, P. Wisdom and Management in the Knowledge Economy; Routledge: New York, NY, USA, 2010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nonaka, I.; Takeuchi, H. The Big Idea: The Wise Leader. Harvard Business Review, May 2019. Available online: https://hbr.org/2011/05/the-big-idea-the-wise-leader(accessed on 14 May 2021).

- Banerjee, A. Knowledge and Wisdom Management. 2014. Available online: http://www.delhibusinessreview.org/v_2n2/dbrv2n2p.pdf (accessed on 25 April 2021).

- Ekmekҫi, A.K.; Teraman, S.B.S.; Acar, P. Wisdom and management: A conceptual study on wisdom management. 10th International Strategic Management. Procedia—Soc. Behav. Sci. 2014, 150, 1199–1204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Nonaka, I.; Chia, R.; Holt, R.; Peltokorpi, V. Wisdom, management and organization. Manag. Learn. 2014, 45, 365–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]