Abstract

This study examines Sylvia Plath’s literary corpus through a biopolitical lens, analyzing how her representations of embodiment—particularly aging, decay, disease, and institutionalization—function as sites of contestation against institutional power. Moving beyond traditional biographical and psychoanalytic interpretations, this research study applies theoretical frameworks from Foucault, Agamben, and Esposito to illuminate how Plath’s work engages with and resists biopolitical structures. Through close readings of “The Bell Jar”, “The Colossus”, and “Ariel”, this study demonstrates how Plath’s aesthetic strategies transform embodied vulnerability into forms of resistance. The analysis explores four key dimensions: the institutionalized body and medical authority; aesthetic politics and the anxiety of aging; the biopolitics of reproduction and maternity; and death as both boundary and transcendence. This study reveals Plath’s corporeal poetics as a sophisticated engagement with the political dimensions of embodiment in the mid-twentieth century, establishing a literary tradition that influences contemporary understandings of bodies as sites of political contestation. Comparative analysis with other confessional poets highlights Plath’s distinctive and systematic approach to biopolitical themes, positioning her work as particularly significant for subsequent feminist theorizations of embodied resistance.

1. Introduction

The intersection of literature and biopolitics has emerged as a crucial area of scholarly inquiry, particularly in understanding how literary texts engage with institutional power structures that govern bodies and populations. This study examines Sylvia Plath’s literary corpus through a biopolitical lens, analyzing how her representations of embodiment function as sites of both subjugation and resistance within mid-twentieth-century institutional contexts. Rather than approaching Plath’s work through traditional biographical or psychoanalytic frameworks, this study applies theoretical perspectives from Michel Foucault, Giorgio Agamben, and Roberto Esposito to illuminate the political dimensions of corporeal experience in her poetry and prose.

The central research question guiding this investigation concerns how Plath’s aesthetic strategies transform representations of bodily vulnerability—including aging, disease, institutionalization, and death—into forms of resistance against biopolitical control. This inquiry addresses a significant gap in existing scholarship, which has predominantly focused on either biographical interpretations of Plath’s corporeal imagery or psychoanalytic readings of her preoccupation with embodiment. By positioning her work within broader frameworks of power and resistance, this study contributes to contemporary discussions about literature’s capacity to critique and reimagine biopolitical structures.

Methodologically, this study combines close textual analysis with thematic frequency mapping and biopolitical theory to create an integrated approach that bridges traditional literary criticism with contemporary political philosophy. The analysis focuses on three central texts, “The Bell Jar” (1963), “The Colossus” (1960), and “Ariel” (1965), examining how these works articulate distinctive forms of embodied resistance that anticipate contemporary feminist theorizations of corporeal politics. As demonstrated in the quantitative visualizations presented throughout this study, Plath’s engagement with biopolitical themes follows systematic patterns that illuminate both personal development and broader political consciousness.

2. Research Background and Theoretical Framework

2.1. Research Background and Significance

Sylvia Plath’s literary corpus presents a profound exploration of embodiment that extends beyond mere autobiographical reflection, establishing a complex terrain where physical existence intersects with sociopolitical forces. Plath’s preoccupation with the body—particularly its deterioration, medicalization, and ultimate dissolution—offers a uniquely fertile ground for biopolitical analysis. As Beardsworth (2022) notes in her examination of confessional poetry during the Cold War, Plath’s work emerged within a historical moment of intensified governmental interest in managing bodies and populations [1]. This context significantly influenced how Plath conceptualized and represented embodied experience, creating what Beardsworth terms a “poetics of doublespeak” where personal bodily narratives simultaneously function as political commentary. While traditional scholarship has predominantly approached Plath’s corporeal imagery through biographical or psychoanalytic lenses, this study adopts a biopolitical framework to illuminate how her representations of aging, disease, and bodily decay function as sites of contestation against institutional power.

The application of biopolitical theory to Plath’s work addresses a significant gap in existing scholarship. Though Lu (2007) has extensively examined the intersection of modernity and biopolitics in literary contexts [2], and Mack (2014) has explored how literature challenges quantitative approaches to human experience [3], few studies have specifically applied these frameworks to Plath’s corporeal poetics. This study thus poses a central question: How does Plath’s literary corpus represent bodies as entities subjected to sociopolitical forces, and how might her aesthetic strategies constitute forms of resistance to biopolitical control? Addressing this question not only enriches our understanding of Plath’s work but also contributes to broader conversations about literature’s capacity to critique and reimagine biopolitical structures.

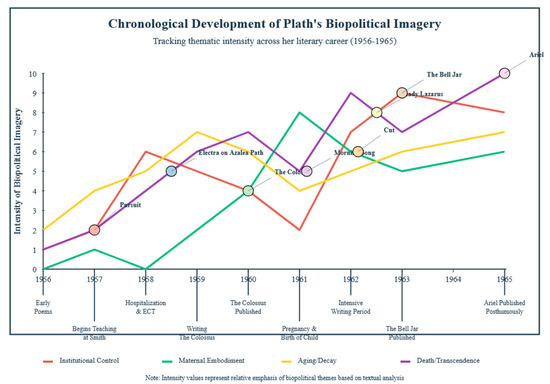

Before proceeding to a detailed theoretical discussion, it is valuable to visualize the chronological development of Plath’s biopolitical imagery throughout her literary career. Figure 1 depicts the development of four pivotal biopolitical motifs—institutional control, maternal embodiment, ageing/decay, and death/transcendence—in the writer’s major works between 1956 and 1965. As shown in the chart, Plath’s engagement with institutional control combines with explosive death imagery after her hospitalization and electroconvulsive therapy in 1958; this reaches a climax in “The Bell Jar” (1963). Her exploration of maternal embodiment, however, peaks around 1961 with both the birth of her child and the poem “Morning Song”, before receding in her later works. Most strikingly, the chart reveals a dramatic intensification of death imagery and transcendence themes during her last years of life, culminating in the posthumously published Ariel collection. Not a random assortment of corporeal concerns, this trajectory accounts for a systematic and coherent biopolitical project that opposed the writer’s life through ethnographic literary techniques. By tracking these developmental patterns, we appreciate how Plath’s corporeal poetics were constructed from experience and major sociopolitical contexts.

Figure 1.

Chronological development of Plath’s biopolitical imagery.

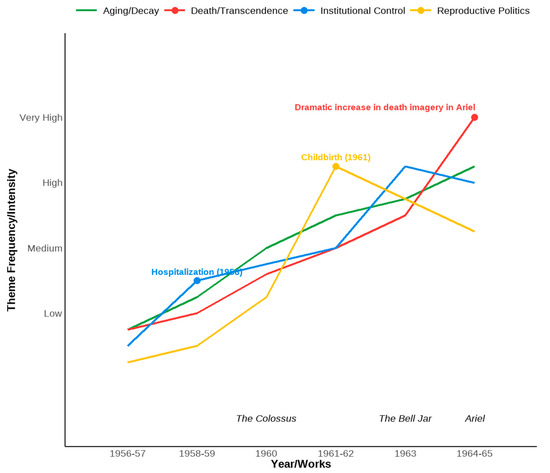

To aid our earlier claims regarding qualitative analysis, Figure 2 contains a frequency analysis of some major biopolitical themes pertinent to Plath’s oeuvre. This visualization aids in understanding the gradual change in the manifestations of institutional control, aging/decay, reproductive politics, and death/transcendence over the course of her career. As shown, the themes of institutional control exhibit a significant rise after Plath’s 1958 hospitalization, which was completed by her writing of “The Bell Jar” (1963). Themes of reproductive politics are most pronounced during her maternal peak (1960–1962), while concerns with aging and decay are ever-present in her works. Perhaps most striking is the increase in imagery of death and transcendence in her last works, especially the collection “Ariel”. This mapping confirms the assertion made earlier that Plath’s relationship with biopolitical themes was more developmental than random and was in answer to personal circumstances and wider sociopolitical situations. The visualization outlines how Plath’s biopolitical consciousness shifted throughout her literary career and becomes more profound, sophisticated, and intensifies in her later works. As Figure 2 demonstrates, this developmental trajectory reflects not random fluctuation but systematic evolution in Plath’s biopolitical consciousness. The visualization reveals how themes of institutional control intensify following her 1958 hospitalization and reach culmination in “The Bell Jar”, while reproductive politics peak during her maternal years (1960–1962), and death imagery dominates her final works. This quantitative mapping provides an empirical foundation for understanding how Plath’s corporeal poetics developed in response to specific encounters with biopolitical institutions.

Figure 2.

Biopolitical themes in Plath’s works.

2.2. Foundations of Biopolitical Theory

The analysis draws from Foucault’s model of biopower and examines his later work from “The History of Sexuality, Vol. 1: An Introduction” and his Collège de France lectures. He explains this as power acquired through the application of “numerous and diverse techniques for achieving the subjugation of bodies and the control of populations” (Foucault, 1978, p. 140) [4] that attempts to moderate life through an “explosion” of mechanisms. This power structure that permeates the body is important in analyzing the controlling bodies with which Plath’s literary illustrations interact. These metaphors can be used to depict and analyze how Plath’s representations of her experiences related to hospitalization, psychiatric treatment, and bodily decline mediate institutional control. In contrast to passively portraying such systems, Plath subverts them through innovative formal and linguistic means, what Schneeberger (2018) calls “narrative embodiments” that counteract being reduced to a medical object [5].

Giorgio Agamben’s interpretation of Foucauldian biopolitics could be enhanced through his concept of “bare life” which was developed in “Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life” (1998) [6]. Agamben’s thesis that modern politics continuously allows people to exist solely as biological organisms bereft of any political identity resonates profoundly with Plath’s illustrations of corpses in institutions. Agamben describes biopolitics as follows: “the production of a biopolitical body is the original activity of sovereign power” (1998, p. 6) [6]. This quote clearly portrays Agamben’s considerations of medical institutions as places where, in Plath’s account, subjectivity is endangered. In “Tulips”, “The Surgeon at 2 a.m.”, and the whole novel “The Bell Jar”, Plath shows us over and over again that medical institutions are places where, in Plath’s account, subjectivity is endangered and bodies are seen as mere biological entities. However, unlike Agamben’s often pessimistic conclusions, Plath’s work suggests the possibility of reclaiming agency through aesthetic production, aligning more closely with Roberto Esposito’s “affirmative biopolitics” as articulated in “Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life” (2011). Esposito argues that rather than merely opposing biopolitical structures, resistance must operate within the “immunitary logic” of modern power, transforming its mechanisms from within—a strategy evident in Plath’s aesthetic reconfiguration of medicalized experience [7].

Esposito’s immunitary paradigm—wherein protection and destruction exist in dialectical relation—provides a particularly nuanced framework for interpreting Plath’s ambivalent representations of bodily boundaries. As Esposito argues, “the negative protection of life…proceeds through the negation of what negates it” [7] (2011, p. 16), a dynamic clearly visible in Plath’s portrayal of bodies that both incorporate and resist external threats. As İmşir (2023) demonstrates in her analysis of female bodies in twentieth-century literature, women writers often deploy immunitary logic to represent how bodies simultaneously resist and incorporate external threats [8]. This theoretical approach helps illuminate Plath’s complex engagement with biological vulnerability, particularly evident in her pregnancy poems and in works addressing medical intervention.

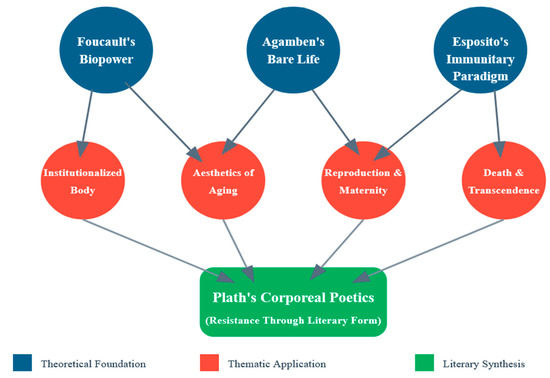

The above-mentioned theoretical intertwining has been provided with the necessary scaffolding within which Plath’s literary involvement with embodiment and institutional power shall be analyzed. In her corporeal poetics, Plath’s poetry, Foucault’s biopower, Agamben’s concept of “bare life”, and Esposito’s immunitary paradigm are understood as shown in Figure 1. This framework demonstrates what an integrated approach to these theories offers in terms of Plath’s work that ranges from the institutionalized body and ageing aesthetics to reproduction and death. These applications are brought together in Plath’s unique literary style displayed in Figure 3, where she employs embodied suffering as an expression of aesthetic defiance. This approach demonstrates the ways in which Plath’s poetry and prose, rather than merely documenting bodily experience, contest the biopolitical regimes that govern and limit corporeal existence with the use of language.

Figure 3.

Biopolitical framework applied to Sylvia Plath’s corporeal poetics.

2.3. Body Politics in Literature

The idea of body politics has a considerable history within the scope of literary studies, especially in the context of feminist criticism. Klinkowitz, J. (2001) claims that since the 1960s, fiction has increasingly incorporated the body as a central place of struggle and argues that Plath’s work was ahead of the curve [9]. In both her poetry and prose, Plath makes bodies the theatres of wars where cultural practices, medicine, and selfhood grapple for power. In any case, what sets her apart from other writers is the stubbornness to depict bodies not only as passive surfaces of power but as subjects who can resist through their weakness.

Smith (2008) argued that affect and narrative serve as central mechanisms of operating within the realm of neoliberal biopolitics, particularly in regard to female bodies [10]. Within Plath’s work, and building on that, Hall (2020) describes a “disability poetics” which antagonizes value-laden, normative assumptions of bodily functionality [11]. Strife between compliance and defiance saturates Plath’s depictions of female embodiment, with the beauty rituals in “Face Lift” to the hospitalized body in “Tulips” clearly expressive of this struggle.

Plath is most commonly associated with the movement swept in along with her centered confessional poetry, which, indeed, happens to be the genre of her life. This branch offers the most profound ground in relation to biopolitical phenomena. Confession, as a category of poetry, displays a pronounced and deliberate association with medical definitions of physical and psychical conditions. In their analysis of Philip Larkin’s melancholia in light of the DSM-5, Mohammad and Alsalim confirm that confessional poetry utilizes labels of illnesses or diseases in a straightforward way [12]. The interface of Plath’s suggestion leads to Finch’s (2020) notion of the poetics of “embodied escess”, which claims embracing the militant state devoid of medical rationality and control [13]. Within medical discourse, Plath positions her speakers simultaneously as patients and critics of institutional authority, creating what Cochran (2019) calls “clean and dirty reading” that both accommodates and contests institutional constraints [14].

2.4. Research Methods and Materials

This study applies a combination of close reading and thematic analysis as the main methods, based on biopolitical perspectives concentrating on the relationships of power that operate in and through the literary representations of embodiment. The analysis is based on three central texts of Plath’s: The Bell Jar (1963) for extended prose engagement with psychiatric hospitalization, her early collection The Colossus (1960) which begins to set the imagery of the body, and Ariel (1965) published after her death which continues the theme of concern with corporeal representation in much more vivid and painful terms.

This approach clarifies how Plath’s mid-twentieth-century literary output responded to concurrent transformations in medical authority, gendered power dynamics, and institutional control.

Rather than focusing on the biographical materials alone, Mack’s criticism flows through the boundaries of texts, which, as she remarks, can be overly textual concerning the context surrounding literature’s production. This study shows how Plath’s formal changes within her texts are parallel, and they are indeed associated with the historical reality of biopower. This study employs quantitative visualization to complement qualitative analysis. Figure 1 illustrates the chronological development of four pivotal biopolitical motifs across Plath’s major works between 1956 and 1965, providing empirical foundation for the subsequent textual analysis. With this, I contend that her work is not solely the articulation of one’s bodily experience but rather an engagement with the politics of the body in the mid-twentieth century, which is much more sophisticated than what proponents of corporeal feminism offer. The methodological integration of quantitative thematic mapping with qualitative close reading addresses what Baumbach and Neumann identify as the challenge of temporal analysis in crisis narratives [15]. This study defines “intensity” in thematic frequency analysis as the convergence of explicit lexical markers with implicit structural patterns, operationalized through systematic coding of corporeal imagery across Plath’s corpus. Text selection prioritizes works spanning Plath’s career (1956–1965) to capture developmental patterns in biopolitical engagement, while excluding juvenilia and fragments to maintain analytical coherence. This study operationalizes “thematic intensity” as the convergence of explicit lexical markers (direct references to medical procedures, aging, reproduction, death) with implicit structural patterns (metaphorical networks, recurring imagery clusters, formal innovations that embody content). Intensity is measured through systematic coding that assigns weighted values to (1) the frequency of corporeal terminology, (2) the metaphorical density of embodiment imagery, (3) formal innovations representing bodily experience (such as fragmented syntax mirroring physical fragmentation), and (4) intertextual references to medical, political, or institutional discourse. The term “maternal peak” designates the period 1960–1962 when Plath’s engagement with reproductive themes reached maximum intensity, coinciding with her experience of pregnancy and early motherhood, evidenced in works like “Morning Song”, “Metaphors”, and “Three Women”. This quantitative foundation supports subsequent qualitative analysis by providing empirical grounding for claims about developmental patterns in Plath’s biopolitical consciousness.

3. The Institutionalized Body: Medical Intervention and Subjectivity

3.1. Psychiatric Power in The Bell Jar

Building on Mohammad and Alsalim’s analysis of how confessional poetry employs medical diagnostic language, Plath’s portrayal of Esther Greenwood’s institutionalization in The Bell Jar (1963) functions as literary diagnosis that both utilizes and critiques medical discourse. Plath’s deeply personal writing reveals the inner workings of trauma, biopower, and postwar American psychiatry. In comparison to the rest of the body, the depiction of ECT in the novel is perhaps the most notable illustration of biopower—the electric codification of institutionalized control over bodies by medicine. Esther’s description of the first ECT session as “something smashing inside my skull, knocking me out” reveals more than personal trauma; it exposes the destructive domination of the individual body by the state’s psychiatric sovereignty (Plath, 1963, p. 143). The novel’s precise attention to bodily sensation—“something bent down and took hold of me and shook me like the end of the world”—transforms medical procedure into visceral testimony of institutional violence. This language exceeds clinical description, creating what Agamben would recognize as testimony from the threshold between life and death, speech and silence. Plath’s innovation lies in rendering this “bare life” condition not as passive victimhood but as the foundation for narrative agency. This accounts for what we might term the “embodied excess” of female mental illness narratives that exceed conventional medical categorization and rational control. Agamben’s concept of “bare life” proves particularly illuminating for understanding Esther’s experience within the psychiatric institution. As Agamben argues in “Homo Sacer”, modern biopolitical structures create conditions where individuals exist in “inclusive exclusion”—included within institutional care while excluded from political subjectivity (1998, p. 21). The psychiatric hospital reduces patients to what Agamben terms “bare life”, existence stripped of political meaning and reduced to biological functions. However, Plath’s innovation lies in transforming this condition of political abandonment into the foundation for narrative agency. Esther’s first-person testimony converts what Agamben sees as speechless suffering into articulate resistance, demonstrating how literary expression can reclaim political subjectivity from within biopolitical exclusion. The temporal pattern evident in Figure 1 confirms this trajectory, showing a marked intensification of institutional control themes following Plath’s 1958 hospitalization, culminating in “The Bell Jar’s” systematic critique of psychiatric authority. Yet, to add to this, Plath demonstrates the dual nature of ECT where it serves as both a medical procedure and a political technique designed primarily to subdue any expression of uncontrolled femininity.

The psychiatric institution’s spatial politics in “The Bell Jar” further explain Foucault’s Disciplinary Power theory. As Schneeberger (2018) argues [5], the hospital’s construction featuring separate wards for various degrees of illness and socio-economic status creates what he calls “narrative embodiments” which denote a physical social stratification. Plath’s materialist focus on the confinement conditions accentuates how the institution’s spaces themselves serve as biopower actors, controlling people’s bodies through surveillance, mechanization of everyday life, and capitonage. This arrangement exemplifies what Beardsworth (2022) calls “Cold War mentality” containment of covert sociopolitical domination that infested American society and portrayed psychiatric hospitals as miniature versions of larger social control systems. Foucault’s analysis of disciplinary institutions in “Discipline and Punish” (1995) provides crucial insight into this spatial arrangement [16]. The psychiatric hospital functions as what Foucault terms a “disciplinary apparatus”, where bodies are rendered docile through surveillance, temporal regulation, and spatial segregation. Plath’s detailed attention to these mechanisms reveals how psychiatric treatment operates not merely as medical intervention but as biopolitical technology designed to normalize deviant subjectivity. The novel’s emphasis on Esther’s physical experiences—the weight of the bell jar, the sensation of electric shock—demonstrates what Foucault identifies as biopower’s investment in “an anatomo-politics of the human body” (1978, p. 139).

Importantly, Esther’s voice throughout the novel’s narrative consistently poses a counter to the medical power. Her telling of her psychiatric history in the first person loses the author’s (Cochran, 2019) analysis of a medicine which is both “a clean and dirty reading” [14]. Esther’s ironic distance, the simultaneous role of a patient and a critic of the institution, challenges the totalitarian claims of psychiatric knowledge. Her statement “the people in the hospital seemed to be a lot sicker than I was” is not only denial, but an example of why she argues that psychiatry is full of erroneous classifications, which, according to İmşir, is a form of adopting a women’s strategy of counter-resistance through narrative reappropriation.

3.2. The Medicalized Female Body

The developing division of mental illness along gendered lines becomes an issue of concern in Plath’s work as it displays how medical language accounts for the female body as a default pathological being. In The Bell Jar, the phenomenon of women being emotionally responsive to dire circumstances is perpetually framed as an illness rather than a sane response to an insane society. This aligns with what Hall refers to as the historical tendency of medicine in women’s so-called “patriarchal” resistance. Esther’s depression after meeting societal expectations of womanhood is not understood as a reasonable response to severely constrained choices, but instead is understood as an individual’s pathology in need of remedy. It is in this admiration that Plath seems to manifest the process of enacting this form of pathology, exposing what Smith argues are the affective means through which neoliberal biopolitics construct and preserve gender normativity.

Both Baumbach and Neumann stress the difficulty that modern narratives of a crisis can provide for genuinely opposing a dominant discourse, and it is clear from the novel that this Dr. Nolan, despite being a female psychiatrist, leads Esther towards accepting patriarchal society instead of fighting it. Alongside this, there is a parallel notion that indeed remains ungrasped within Baumbach and Neumann’s discourse: Plath shows us that even in the most oppressive of discourses that strive to alienate women from each other, there exists a possibility of connection and recognition. The novel illustrates how the so-called adjustment languages of psychiatry serve to sustain and deepen negative social stereotypes about feminine professions and sex roles.

“Ward Poetics”, a term coined by Lu who argues that poetry serves to highlight the body, can be found in “The Bell Jar” and “Tulips”. Her focus on material particulars features the “frost of the iron bed” and the “awful babble of moans and tears”. In juxtaposing these remembrances, Plath describes horrid environments that have, according to Felt, severed the body’s essence and turned it into an “electrified body” [17]. Plath’s innovation rests on representing the medicalized female body not merely as an object, but as a sentient one who feels power relations and contests them.

3.3. Power Structures in Doctor–Patient Relationships

These constructs stand in contrast to Mack’s argument that institutional authority often neutralizes patient narratives under the guise of clinical objectivity.

Within Plath’s works, patient objectification exists both as medical practice and as a literary subject. With reference to “The Bell Jar”, Esther recalls an occasion when her body became “the object of attention of a whole posse of strange men”. This objectification includes not only physical examination but also psychological evaluation in which the patient’s thoughts and feelings are reduced to symptoms that need to be catalogued instead of being actively engaged with. This construct mirrors what İmşir identifies as “exceptional bodies” which feature in women’s writing of the twentieth century—bodies that are rendered overexposed as medical subjects of examination while simultaneously being absent as autonomous agents. Plath’s elaborate account of this process is not simply a matter of personal reflection but a strong indictment of the ways in which the medical gaze monopolizes the construction of patient subjectivity.

Through narrative and poetic forms, the restoration of bodily autonomy marks the most telling interjection Plath makes into biopolitical argumentation. Her work operates what Esposito might consider “affirmative biopolitics” in that it transforms life into an aesthetic object while reclaiming it from the controlling grasp of institutions. “Lady Lazarus” and “Tulips”, along with other poems, turn the passive recipient of medical attention into an active medical participant who interprets, defends, and even actively contests the treatment being meted out to them. This, as Beardsworth notes, is the peculiar mastery of confessional poetry from the Cold War era: its capacity to generate alternative centers of power through subjective and personal accounts. Plath’s accomplishment goes further than merely narrating the workings of medicine; she fundamentally contests its epistemological roots by arguing that to create art is, in essence, to resist biopolitical subjugation.

4. Aesthetic Politics and Anxiety of Aging

4.1. “Face Lift” and Bodily Modification

In Plath’s “Face Lift” from her collection “The Colossus” (1960), surgery becomes a form of biopower as it exemplifies what Foucault defines as power that disciplines through the self-regulation of individuals. The poem’s clinical opening—“You bring me good news from the clinic”—immediately establishes medical authority as the arbiter of feminine worth, with “good news” suggesting that surgical intervention represents salvation rather than simply cosmetic modification. The speaker’s subsequent description of her aging self as a “dewlapped lady/I watched settle, line by line, in my mirror” creates a temporal double, positioning her pre-surgical identity as a form of social death that precedes biological mortality. The metaphor of “settling” evokes both gravitational inevitability and resigned acceptance, while “line by line” suggests both facial wrinkles and textual inscription—aging as a form of unwanted writing upon the body. When the speaker anticipates that her post-surgical face will be “Marble clean”, the metaphor promises purification yet simultaneously evokes mortality through marble’s associations with tombstones and classical statuary, revealing how surgical renewal paradoxically approaches its own negation. The precision of the surgery constitutes what İmşir calls an “exceptional body” in women’s twentieth-century literature—one that defies as much as it conforms to dominant constructions. Plath’s construction of the face as “stamped thin by the seasons” describes ageing as more than just a biological phenomenon; it is a system of social marking resonance with confessional poetry’s ability to reveal the intersection of the political and the personal (Beardsworth 2022) [1]. Yet Plath goes further than documenting beautification processes to question the role of aesthetic ideals as tools of societal subjugation.

This metaphor evokes a paradox: while suggesting aesthetic renewal, the phrase “Marble clean” also conjures imagery of death and permanence associated with tombstones and classical statuary, thus illustrating how aesthetic intervention embodies Esposito’s notion of immunitary contradiction.

The maximum level of conflict between self-transformation and social expectation occurs in the last lines of the poem, where the speaker’s surgical self-rejuvenation is celebrated as both an achievement and a form of erasure. The affirmation, “I grow backward”, points to what Baumbach and Neumann call “temporalities of crisis”—a disturbance in the order of time tracking that attends to social worries and reinforces them at the same time. Plath’s accomplishment rests with presenting cosmetic surgery as a matter of choice, not individualistic, but as a political act situated in systems of value and power. The poem, near its conclusion, reveals how aesthetic interventions simultaneously embrace social norms while exposing the violence required to enforce them.

4.2. Mirrors and Bodily Identity

The mirror functions in Plath’s work as both a literal object and powerful metaphor for systems of self-surveillance that regulate female embodiment. In her poem “Mirror” from “Crossing the Water” (Plath, 1971, p. 34), the reflective surface claims that “I am silver and exact. I have no preconceptions”, establishing an illusion of objective truth that masks how visual assessment itself constitutes a form of disciplinary power. This personification aligns with what Hall identifies as the “prosthetic” nature of evaluative technologies—objects that extend institutional judgment into private space. The mirror’s claim to neutrality—“I am not cruel, only truthful”—reveals how aesthetic standards present themselves as natural rather than constructed, embodying what Lu describes as modernism’s complex engagement with technologies of self-regulation. Plath’s innovation lies in making visible the mirror’s dual function as both a reflective tool and enforcement mechanism.

The visual evaluation system operating through mirrors in Plath’s poetry reveals the particular vulnerability of female bodies to external assessment. When the woman in the “Mirror” approaches the reflective surface “searching my reaches for what she really is”, Plath articulates how identity formation becomes inseparable from visual approval. This dynamic exemplifies what Mohammad and Alsalim identify as the intersection between external validation and internal subjectivity that characterizes modern melancholia. The poem’s progression toward the devastating final image—“In me she has drowned a young girl, and in me an old woman/Rises toward her day after day, like a terrible fish”—demonstrates how the aging female body becomes monstrous through continuous exposure to visual judgment. This transformation aligns with what Finch terms the “embodied escess” of female embodiment that exceeds normative categorization.

The power dynamics of seeing and being seen permeate Plath’s work, establishing visual assessment as a primary mechanism of biopolitical control. In poems like “The Applicant” and “The Munich Mannequins”, female bodies exist primarily as objects of male evaluation, reflecting what Klinkowitz identifies as the objectifying gaze that dominated mid-century American culture. However, Plath complicates this dynamic by having her speakers simultaneously occupy positions of observer and observed, creating what Schneeberger describes as “embodied cognition” that destabilizes simple subject–object divisions. The mirror reveals not just external appearance but subjectivity itself as partially constructed through visual feedback, suggesting what Beardsworth terms the “doublespeak” inherent in cold war constructions of selfhood—at once autonomous and thoroughly regulated. This consistent engagement with aging and bodily decay across Plath’s career, as visualized in Figure 2, underscores how temporal anxieties function as persistent sites of biopolitical control.

4.3. Temporal Politics of Aging

The interplay between the valuation of women and their age has emerged as a primary concern in Plath’s writings, portraying how even aging becomes infused with hypergonic issues of female expectation. In Plath’s words, “Perfection is terrible, it cannot have children” (Munich Mannequins), which asserts that reproductive capabilities are at odds with youthful beauty, captures what İmşir describes as the double-blind female embodiment. This paradoxical norm reinforces what Smith characterizes as the emotional requirements of a postmodern capitalist gendered economy—a demand to be both youthful and a mother at the same time. Heidy exposes these discrepancies, highlighting the precariousness of normative female embodiment, suggesting that women endure, as Baumbach and Neumann term it, “temporality of crisis” with each year passing by devaluing their body.

In Plath’s poetry, the biological clock acts as a form of social control that disciplines women’s bodies through the use of time. In her poems “Childless Woman” and “Barren Woman”, Felt argues that feminine value is inherently tied to the ability to reproduce, giving rise to the so-called “electrified body” that is always on standby to respond to temporal demands. The speaker’s claim in “Childless Woman” that “My landscape is a hand with no lines” makes infertility a form of geographical desolation, illustrating what Mack refers to as the commodification of human worth based on productive output. Nevertheless, Plath’s work also contests this simplification by offering other ways of artistic creation which serve as artistic expression. This stance serves what Finch calls the retrieval of “irrational” embodiment as a site of creative agency rather than as a form of social control.

Plath’s poetry captures how the processes of the temporally persistent movement are embedded in socio-cultural expectations. In “Face Lift”, the speaker suggests that “Now she’s done for, the dewlapped lady/I watched settle, line by line, in my mirror”, which shows that aging has come to be treated as a form of social death that precedes physical death. This impression reveals how aging operates as both social conformity and transgression, simultaneously meeting and defying cultural expectations of feminine embodiment. Plath’s achievement is to make temporal experience in its own right political; Hall refers to this as “disability temporality” where the expected normative movement is absent of the body’s progress. As the years pass, Plath looks unadorned, with more and more wrinkles. While her eyes and nose grow thin, her face becomes rounder, concealing her jaw. Her shoulders droop and shift forward. Through my mind, like flags marking the changing seasons, the years, the onslaughts of my wrinkling face.

5. Biopolitics of Reproduction and Maternity

5.1. The Duality of the Gestating Body

Sylvia Plath’s engagement with pregnancy and maternity reveals profound biopolitical dimensions where the maternal body becomes a contested site of personal experience and social regulation. In poems like “Metaphors” from “The Colossus” (1960), the pregnant speaker describes herself as “a means, a stage, a cow in calf” (Plath, 1960, p. 41), exemplifying what Mack identifies as modernity’s tendency to “quantify human experience through measurable outcomes” (2014, p. 73) [3], thereby reducing women to their reproductive function. This representation illustrates Beardsworth’s concept of “poetics of doublespeak”, where personal narratives simultaneously encode political critique. The pregnant body in Plath’s work functions as what İmşir terms a “body of exception”—simultaneously valorized for its reproductive capacity and subjected to institutional control. The quantitative analysis presented in Figure 2 reveals that maternal embodiment themes reached their apex during 1960–1962, corresponding with both Plath’s personal experience of motherhood and her composition of works like “Morning Song”.

Plath’s fertility imagery in “Tulips” establishes reproduction as both biological process and social performance. The hospitalized maternal body becomes subject to what Schneeberger terms “narrative embodiments” positioning reproduction within frameworks of professional expertise. In “Three Women”, the hospital setting transforms maternal bodies into objects of what Cochran describes as “clean and dirty reading”—simultaneously medicalized and intimately experienced. Through three distinct voices—successful mother, woman who miscarries, and mother giving her child up for adoption—Plath illustrates how institutional power differentially affects bodies based on their conformity to reproductive expectations, demonstrating what Finch terms the “embodied escess” of female reproductive experience that exceeds normative categorization.

5.2. Power Dynamics in Mother–Child Relations

A close examination of the mother–infant bond within Plath’s work constitutes evidential traces of power relations which operate on more encompassing biopolitical frameworks. In “Morning Song”, the phrase “Love set you going like a fat gold watch” captures the reality of a child that is both a product and a determinant of maternal life, creating what Felt refers to as an “electrified body” that is mechanically responsive to external stimuli. This interaction exemplifies what Lu describes as the modernist predicament of the body: the problem of autonomy and liability. The maternal body is perpetually responsive to stimuli which, to some degree, Smith defines as the affective labor which converts the biological potential into a social obligation.

While portraying poems like “Child” and “Candles”, the first impression of ambiguity gives way to a blend of fondness and hatred that contextually defines maternal relations toward children and vice versa. This complex blend of emotions evokes what Mohammad and Alsalim call the indicative sadness of the mid-twentieth-century confessional poetry. The speaker’s wish to fill her child’s “clear eye with colour and ducks” in “Child” collides with wanting to protect him from “the ceiling’s stare”, demonstrating what Finch refers to as the tragedy of motherhood—the act of wanting to protect while painfully knowing she cannot. The interplay of these dynamics results in what Baumbach and Neumann call “crisis temporalities”—periods shaped by opposing forces.

5.3. Beehive Imagery and the Collective Body

The beehive appears in Plath’s poetry as a striking biopolitical image conveying conflict between the individual and the group. In her “Bee Sequence” poems, especially “The Arrival of the Bee Box” and “Stings”, the hive embodies what Mack suggests is the alarming contemporary notion of considering human societies as biological systems in need of management. The speaker’s ambivalent attitude towards the hive—both awed and terrified—demonstrates Beardsworth’s “doublespeak” where political criticism is wrapped up within personal encounters.

These power relations in the beehive, in particular that of the queen and the workers, give Plath a lens through which to analyze reproductive structures of dominance. In “Stings”, the proclamation “They thought death was worth it, but I/Have a self to recover, a queen” subordinates reproductive freedom to political defiance, which suggests what Finch calls the embracing of “embodied escess.” This metamorphosis of the queen bee into a figure representing feminine power relabels reproductive potential as autonomous agency instead of a biological fate.

The annual productivity and inactivity periods of the hive in “Wintering” reflect how reproductive biopolitics operates through temporal cycles that both evaluate and control fertile bodies. As the speaker states that “the bees have got rid of the men”, this calls for the hive as an alternative social arrangement, capturing what Hall refers to as the embodied resistance utopian potential. This is in line with Felt’s “electrified body”, which evokes new connections through vulnerability, changing a biological metaphor into a powerful political commentary on personal autonomy in the face of collective demands.

6. Death, Transcendence, and Poetic Legacy

6.1. Biopolitical Reading of Death Imagery

In Plath’s imagery of death, there is more than preoccupation on a personal level as it reflects her sophisticated relationship with biopolitical boundaries. Her poems illustrate death as the supreme limit of control on institutionalized bodies, creating what Foucault would recognize as a paradoxical space where power, in turn, both accumulates and dissipates. In “Lady Lazarus”, the speaker’s opening declaration—“I have done it again./One year in every ten/I manage it”—establishes suicide attempts within a temporal framework that transforms personal trauma into a performed spectacle. The mechanical precision of “one year in every ten” reduces profound suffering to statistical regularity, revealing how even the most intimate experiences become subjected to institutional timing and measurement. The verb “manage” carries dual connotations of both achievement and control, suggesting how survival itself becomes a form of resistance to institutional expectations. When the speaker proclaims “Dying/Is an art, like everything else”, she repositions suicide from medical pathology to aesthetic practice, challenging medical authority’s monopoly over defining life and death. This transformation exemplifies what Beardsworth identifies as confessional poetry’s capacity to create alternative frameworks of knowledge that contest institutional expertise. Beardsworth notes that this is confessional poetry’s ability to give witness and, hence, create new paradigms of knowledge. The suicide attempts recounted in the poem serve to İmşir’s “bodies of exception” which, in their utter fragility, escape total institutional control. However, Plath complicates this resistance by showing how even death becomes incorporated into biopolitical systems, with the speaker noting that each resurrection makes her “a valuable” commodity, suggesting what Smith describes as the neoliberal tendency to extract value from all forms of embodied experience.

The medical management of death emerges as a central concern in poems like “Tulips” and “The Surgeon at 2 a.m.”, where dying bodies become subjects of institutional intervention. These representations exemplify what Mack identifies as modernity’s preoccupation with quantifying and regulating even the most intimate bodily processes. The hospitalized speaker in “Tulips” describes herself as “learning peacefulness, lying by myself quietly/As the light lies on these white walls”, suggesting what Hall terms the “disability temporality” imposed by medical environments. Yet this apparent passivity masks a profound challenge to institutional authority, as the speaker’s internal detachment—“I am nobody; I have nothing to do with explosions”—creates what Schneeberger describes as “embodied cognition” that exceeds medical categorization. This tension between external regulation and internal resistance reveals how death functions simultaneously as a biological event and political boundary, exposing the contradictory nature of medical discourse that both preserves and negates life. The reconstruction of power relations through death imagery reaches its apex in “Edge” and “Contusion” from the posthumously published “Ariel” collection (1965), where the dying body achieves a form of agency through its very dissolution. As Plath writes in “Edge”, “The woman is perfected./Her dead/Body wears the smile of accomplishment” (1965, p. 90), establishing death not merely as capitulation to biological inevitability but as deliberate transgression of institutional boundaries. The speaker’s observation in “Edge” that the dead woman is “perfected” suggests what Finch terms the “embodied escess” of female embodiment reconfigured as a source of power rather than a limitation. This transformation aligns with what Baumbach and Neumann identify as the “temporalities of crisis” that characterize modern embodiment—moments where “conventional chronology collapses to reveal alternative possibilities” (2023, p. 27) [15]. The poem’s final image of the body “worn by her smile of accomplishment” establishes death not merely as capitulation to biological inevitability but as the deliberate transgression of institutional boundaries, suggesting what Lu describes as modernism’s capacity to reimagine embodied existence beyond conventional limitations. Plath’s achievement lies in rendering death not merely as a biological terminus but as a political frontier, revealing how even the most intimate bodily processes remain inseparable from broader systems of power and resistance.

6.2. Transcending Physical Limitations Through Poetry

Language emerges in Plath’s work as a primary medium through which embodied experience transcends physical limitations. Her poems reveal writing itself as biopolitical practice—an assertion of subjective agency against institutional objectification. In “Lady Lazarus”, the declaration “Out of the ash/I rise with my red hair/And I eat men like air” establishes poetic expression as a form of embodied resistance, aligning with what Mohammad and Alsalim identify as the characteristic capacity of confessional poetry to transform personal suffering into cultural critique. This transformation exemplifies what Beardsworth terms the “poetics of doublespeak”, characteristic of Cold War confessional writing—a strategic deployment of personal testimony that simultaneously functions as political statement. The speaker’s resurrection through language suggests what İmşir describes as the potential of literary expression to reconfigure “bodies of exception” as sources of authority rather than mere objects of management.

The imagery of liberation and transcendence permeates poems like “Ariel” and “Fever 103°”, where physical boundaries dissolve through linguistic transformation. In “Ariel”, the speaker’s declaration “And I/Am the arrow,/The dew that flies/Suicidal, at one with the drive” establishes poetic consciousness as capable of exceeding corporeal constraints, suggesting what Felt terms the “electrified body” that generates new connections through its very vulnerability. This transcendence aligns with what Hall identifies as the utopian potential of embodied resistance to conventional power structures—the capacity to imagine alternative forms of physical existence through aesthetic innovation. The poem’s progression from embodied experience to expansive consciousness exemplifies what Klinkowitz describes as post-1960s fiction’s preoccupation with bodily transformation as a site of political possibility. Plath’s achievement lies in rendering transcendence not merely as metaphysical aspiration but as concrete poetic practice, suggesting what Smith describes as the affective labor that transforms embodied experience into cultural production.

Plath’s work features creative production functions that serve as a resistance to control from the biopolitical lens and position poetry as an alternative mode of embodiment outside the reach of institutional subjugation. The self-autobiographical “Lady Lazarus” and “Daddy” demonstrate the manipulation of autobiographical content into a formalized aesthetic composition that evidences what Cochran describes as “clean and dirty reading”. The imposition by the speaker in “Lady Lazarus” that “For the eyeing of my scars, there is a charge” suggests that artistic production is figuratively claiming the bodily experience from the medicalization of the body. This reconfiguration demonstrates how aesthetic production can transform embodied experience into forms of cultural resistance that operate outside conventional medical and institutional frameworks. Mack advances the proposition that literature has the ability to negate the dominant overarching and reductionist frameworks in the humanities and human experience. The transformation of “embodied escess” is what is synonymous to identity of value on discourse and not on tangible, quantifiable results. These poems serve not only as witness for life accounts but also as discourse on intervention, demonstrating how aesthetic production is a mode of resistance to the normalization of biopolitical control.

6.3. Cultural Legacy of Plath’s Body Politics

Plath’s corporeal poetics have exerted profound influence on contemporary women’s embodied writing, establishing what might be termed a biopolitical literary tradition. Her unflinching engagement with bodily vulnerability anticipated what İmşir identifies as the characteristic preoccupation of twentieth-century women’s literature with “bodies of exception” that both challenge and reinforce institutional norms. Contemporary poets like Anne Sexton in “To Bedlam and Part Way Back” (1960) [18] and “Live or Die” (1966), Adrienne Rich, and Sharon Olds have extended this approach, developing what Beardsworth terms “poetics of doublespeak” (2022, p. 12) [1] that encode political critique within personal narrative. As Middlebrook demonstrates in her biography of Sexton, this confessional mode “transformed female embodiment into a site of political consciousness” (1991, p. 201) [18]. This legacy extends beyond poetry to inform fiction, memoir, and performance art, creating what Schneeberger describes as “narrative embodiments” that position personal experience within broader political contexts. Plath’s achievement lies not merely in documenting bodily experience but in demonstrating how corporeal representation itself constitutes a form of political intervention, suggesting what Klinkowitz identifies as the increasing recognition of bodies as sites of political contestation in post-1960s literature.

The nuances of the feminist critique on Sylvia Plath show that her view of biopolitics is quite contradictory, suggesting that she exists in a paradox. Her work falls into multiple categories, ranging from trauma-centric psychoanalysis to sociopolitical critical theory. This variety of interpretations arises from what Hall describes as focus and its opposition in disability poetics “on the one hand, on the lived experience of particular individuals and on the other, the sociopolitical context that structures their life.” As problematic as this may seem, biopolitical positions have proven especially helpful in analyzing corporeal imagery in her work because they demonstrate how, as Smith argues, Plath continuously engages with the affective mechanisms of power over and alongside bodies. This perspective does not only account for Plath’s literary anomalies, but also sheds light on her relations to the issues of embodiment in literature, which as Cochran puts it, reflect the primary significance of the texts which “construct and critique the dominant discourses of the management of bodies”.

It is not only literature, but also the cultural understanding of Plath’s work that informs and expands her biopolitical vision. Her work is thought to precede contemporary theories on embodiment, especially the “electrified body” in Felt that blends biological and political identities. Baumbach and Neumann remark on the emergent understanding of “crisis temporality”, which refers to the dislodging of identity through technological, environmental, or political changes and contemporary embodiment while simultaneously integrating the physical aspect in Plath’s work. The pregnant woman in the hospital to the elderly woman all both material manifestations of Plath’s concern with the body, which allows one to explore how modern institutions still exercise power through and over bodies in modernity and postmodernity, as suggested by Lu who describes the conflict between freedom and control in contemporary living. Drawing on this, it may be fruitful to explore how new technologies bypass the issues within the biopolitics that Plath delineated. Mack speaks of new forms of quantification that capture sensitive experience and render it into objective data. To more precisely situate Plath’s biopolitical poetics within the broader landscape of mid-twentieth-century confessional poetry, comparative analysis with her contemporaries reveals distinctive approaches to embodiment as a site of institutional control. While Anne Sexton primarily explored the medicalization of female sexuality through direct confrontation with reproductive taboos in works like “The Abortion” and “The Ballad of the Lonely Masturbator”, Plath developed a more systematic critique of how institutional power operates upon bodies themselves. Robert Lowell positioned bodily experience within broader historical frameworks in “Life Studies” and “For the Union Dead”, treating personal embodiment as a metaphor for cultural and political decline rather than examining medical authority as a biopolitical mechanism. John Berryman’s “Dream Songs” engaged with institutional structures primarily through psychological rather than corporeal registers, focusing on academic and social surveillance rather than medical control over bodies.

This comparative perspective illuminates Plath’s distinctive contribution to confessional poetry: where her contemporaries addressed various aspects of embodied experience, Plath consistently interrogated how institutional power operates directly upon and through bodies as sites of both subjugation and resistance. Her systematic engagement with medical authority in “The Bell Jar”, reproductive politics in “Three Women”, and aging as biopolitical control in “Face Lift” and “Mirror” distinguishes her work within the confessional tradition. This sustained focus on what we might term “corporeal biopolitics” explains why Plath’s approach has proven particularly influential for subsequent feminist theorizations of embodied resistance, establishing a literary tradition that continues to inform contemporary understandings of bodies as contested political territories. It is Plath who shows poetic representation as a strong mode of resistance, thereby claiming literature as a vital force in redefining the dialectic between bodies, power, and institutions.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author, Y.X., upon reasonable request.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Beardsworth, A. Confessional Poetry in the Cold War: The Poetics of Doublespeak; Springer Nature: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, S.H. Chinese Modernity and Global Biopolitics: Studies in Literature and Visual Culture; University of Hawaii Press: Honolulu, HI, USA, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Mack, M. Philosophy and Literature in Times of Crisis: Challenging Our Infatuation with Numbers; Bloomsbury Publishing USA: New York, NY, USA, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. The history of sexuality volume I. In Feminist Studies; Routledge: London, UK, 1978; pp. 61–66. [Google Scholar]

- Schneeberger, A.F. Narrative Embodiments: Embodied Cognition in the Post 1945 American Novel. Doctoral Dissertation, University of Nevada, Reno, NV, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Agamben, G. Homo Sacer: Sovereign Power and Bare Life; Heller-Roazen, D., Translator; Stanford University Press: Stanford, CA, USA, 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, R. Immunitas: The Protection and Negation of Life; Hanafi, Z., Translator; Polity: Cambridge, UK, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- İmşir, Ş. Health, Literature and Women in Twentieth-Century Turkey: Bodies of Exception; Routledge: Oxford, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Klinkowitz, J. Fiction: The 1960s to the Present. In American Literary Scholarship; Duke University Press: Durham, NC, USA, 2008; pp. 335–364. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, R. More than a Feeling: Affect, Narrative, Neoliberalism; Rutgers The State University of New Jersey, School of Graduate Studies: New Brunswick, NJ, USA, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- Hall, A. (Ed.) The Routledge Companion to Literature and Disability; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 412. [Google Scholar]

- Mohammad, A.G.; Alsalim, H.F.A. Despairs Verses: Decoding Melancholia in Philip Larkins Selecting Poems Through the DSM-5 Lens. Humanit. Nat. Sci. J. 2024, 5, 118–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finch, M. Unreasonable Blackness: Black Women Writing Madness (1970–Present). Doctoral Dissertation, Brandeis University, Waltham, MA, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Cochran, J.M. Clean and Dirty Reading: Constructing and Rejecting the Hygienic Imagination from Salinger to Egan. Doctoral Dissertation, Baylor University, Waco, TX, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Baumbach, S.; Neumann, B. (Eds.) Temporalities in/of Crises in Anglophone Literatures; Taylor & Francis Group: Abingdon, UK, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Foucault, M. Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Felt, L.D. “ Plugging In”: Disability and the Body Electric in Contemporary American Literature; Stanford University: Stanford, CA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Middlebrook, D. Anne Sexton: A Biography; Vintage: New York, NY, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).