1. Introduction

In his foreword to the All-Party Parliamentary Group document

Creative Health Review (2023), Alan Howard writes that ‘the creative health proposition is simply the expression of the ancient wisdom that the exercise of the creative imagination is beneficial to our health and wellbeing’ [

1] (p. 8). Howard outlines how the practices designated by the term ‘creative health’ can help people to stay well, recover better, and ‘enjoy an improved quality of life throughout the life course’ [

1] (p. 8). Although no direct reference is made to philosophy, the notion of the ‘good life’ is at the heart of the policy recommendations laid out by the group. Buoyed by the belief that a health and care system fit for the twenty-first century should be health-creating not just illness-preventing, the authors of the report demonstrate a tacit commitment to the pursuit of human flourishing.

The purpose of this paper is to examine the value of art for life by situating this concept of creative health within the broader context of the ‘art of living’. French philosopher Pierre Hadot’s influential volume,

Philosophy as a Way of Life: Spiritual Exercises from Socrates to Foucault (1995), argues that philosophy in the ancient world presented itself as a ‘therapeutic’, intended to alleviate human anguish [

2] (p. 265). According to Hadot, both art and philosophy have the power to liberate us from mundane concerns and lasting disquiet, redirecting our attention to the ‘infinite value’ of our presence in the world [

2] (p. 259). This invitation to reconnect with ancient therapeutics resonates with Friedrich Nietzsche’s designation of the philosopher as a ‘cultural physician’. By supplementing Hadot’s ‘art of living’ with a Nietzschean genealogy of value, it is possible to question more deeply the extent to which art and creativity serve to ameliorate life today. A Nietzschean critique of the values underpinning contemporary discourses of creativity and creative health will reveal competing ideas about the value of art for life, illuminating what can and cannot be thought of within the ambit of neoliberal ideology. In challenging dominant habits of thought, this approach yields significant conclusions on how to live well, and creatively.

2. The Art of Living

Pierre Hadot’s

Philosophy as a Way of Life (1995) is a collection of essays which expands and elaborates on his

Exercices spirituels et philosophie antique, originally published in 1987. In his discussion of the spiritual exercises routinely practiced by the Hellenistic and Roman schools of philosophy, Hadot argues that ancient philosophy was a concrete attitude and determinate lifestyle, which engaged the whole of existence: an ‘art of living’ [

2] (p. 83). According to Hadot, each philosophical school had its own therapeutic method ‘but all of them linked their therapeutics to a profound transformation of the individual’s mode of seeing and being’ [

2] (p. 83).

On Hadot’s interpretation of the ancients, spiritual exercises are methods in ‘how to live freely and consciously’ [

2] (p. 86). Whether through dialogue, meditation, reading, or other forms of training, the goal of the exercises is to raise the individual ‘from an inauthentic condition of life, darkened by unconsciousness and harassed by worry, to an authentic state of life, in which he attains self-consciousness, an exact vision of the world, inner peace, and freedom’ [

2] (p. 83). This radical conversion represents healing from ignorance and from the sad passions spawned by fear of fortunes outside our control. Accordingly, the enlightened philosopher is to be distinguished from fellow citizens by superior moral conduct, a proclivity for speaking frankly, and by distance from conventional values (including disdain for wealth). Socrates is probably the most famous exemplar of the philosopher who lived by his teaching, refusing to settle for the quiet life if to do so was to cease asking how to ‘live well’. In this respect, the good life manifests itself through a ‘style’ of being in the world and not through mere discourse alone.

The art of living entails a commitment to spiritual exercises but does not equate to the cultivation of a purely private, egocentric way of life. As Ryan Harte observes, ‘counterintuitively, attaining self-consciousness involves self-transcendence, moving beyond the confines of the self and aligning one’s perspective with universal Reason, or Logos’ [

3] (p. 63). Hadot claims that in attending closely to the ‘infinite value’ [la valeur infinie] of ‘each instant’ of life, the ancient philosopher accedes to ‘cosmic consciousness’ [

2] (p. 85). Through sustained concentration on the present moment, the Stoics and Epicureans were able to liberate themselves from the anguish of the passions—from those things in nature which do not depend on us. By suspending all worldly projects, we discover ‘the infinite value and unheard-of-miracle of our presence in the world’ [

2] (p. 259). This awareness abrades the sense that one is an isolated individual. The philosopher may stand back from the values of the

polis but as a citizen remains vitally connected to the life of the community. Indeed, one attains ‘full awareness of the fact that that one is part of the cosmic whole, as well as part of the whole formed by the city of those beings which share in reason’ [

2] (p. 283). In this regard, Hadot proposes that the Stoics were saying something closely akin to Einstein when he denounced the ‘optical illusion of a person who imagines himself to be a separate entity, while he is really a part of that whole which we call the universe’ [

2] (p. 283).

This elucidation notwithstanding, Hadot acknowledges that it is very difficult for human beings today to comprehend the ancient practice of philosophy as a way of life. This is partly because of the contemporary professionalization of philosophy but it is also because habitual, utilitarian perception is necessary for everyday tasks. Hadot follows Bergson in asserting that in order to live ‘mankind must “humanize” the world,’ render it into ‘an ensemble of “things” useful for life’, discarding from the totality of the real all those things of no immediate use value [

2] (p. 258). If this means that the average person ‘has lost touch’ with the world

qua world [

2] (p. 273) and treats it merely as a means of satisfying desires, some medium must be found to enable us to ‘imagine what cosmic consciousness might signify for modern man’ [

2] (p. 255).

It is here that the value of

art for life comes to the fore. Hadot cites Bergson’s claim that when artists look at something they ‘see it

for itself’ rather than

for them [

2] (p. 254). Like Merleau-Ponty, Bergson considers ‘the aesthetic perception of the world as a kind of model for philosophical perception’ [

2] (p. 254). This mode of perception is ‘disinterested’ in the Kantian sense of reflective aesthetic judgment. In the contemplation of beauty or sublimity, judgment is grounded in the sensuous experience of the subject without it being an item of personal ‘interest’. In other words, something is physically experienced as being ‘of me’ without my having investment in it as an agent. Examples might include the poetic epiphany described by writers such as Blake and Claudel but perhaps the experience is felt most intensely through music and dance. These aesthetic encounters liberate us from seeing the world in instrumental terms as a resource for action. Indeed, Gianni Vattimo describes this experience as the suspension of our habitual relationships with the world, revealing ‘the real foundation of a new world’ [

4] (p. 99). In a similar vein, Hadot likens the Stoic concentration of attention on ‘one instant’ of existence to a poetic perception of nature: ‘the world then seems to come in to being and be born before our eyes’ [

2] (p.260). In experiencing ourselves as a part of that ‘movement of growth and birth by which things manifest themselves’, we are ‘born along with the world’ [

2] (p. 260).

This is tantamount to the claim that the art of living is both a philosophical practice and an aesthetic attitude. Importantly, it is through the latter that the former may be more readily realized in our current technological age. In his work on philosophy as a way of life, Hadot accords a particular importance to modern art. For him, the ‘experience of modern art … allows us to glimpse—in a way that is, in the last analysis, philosophical—the miracle of perception itself, which opens up the world to us’ [

2] (p. 256). In sum, art and aesthetic practice are of especial value for life in an age in which philosophical discourse has become highly specialized and is otherwise remote from ordinary experience. It is through artistic rather than philosophical activity that people today might come to lead ‘examined’ lives.

3. Nietzsche’s Genealogy of Values

According to Hadot, from the end of the eighteenth century onward, philosophy became ‘indissolubly linked to the university’ with only a ‘few rare exceptions like Schopenhauer or Nietzsche’ pursuing philosophy outside its walls [

2] (p. 271). He notes that the latter were both thinkers ‘steeped in the tradition of ancient philosophy’ and that their work invites us ‘to radically transform our way of life’ [

2] (p. 272). This affinity is particularly pronounced in the writings of Nietzsche, who extols the value of art for life from his early meditations on Attic tragedy onwards. In a note from 1873, Nietzsche attributes to the ancient art of living both aesthetic and civic importance: ‘The philosopher’s product is his

life (which occupies the most important position,

before his

works). His life is his work of art, and every work of art is first turned toward the artist and then toward other men’ [

5] (p. 109). Like Hadot, Nietzsche sees the value of art beyond items of creative production, investing the aesthetic with existential significance as a primary mode of being.

As noted previously, Hadot exalts the ‘infinite value’ of our presence in the world revealed through Stoic and Epicurean spiritual transcendence. However, it is here that Nietzsche departs from Hadot’s perspective, calling in to question the

value of values that are ‘accepted as given, as fact, as beyond all question’ [

6] (p. 8). In orchestrating a critique of values, Nietzsche turns a skeptical eye away from the prevailing values of the day towards the conditions of their emergence. He describes this practice as requiring ‘a knowledge of the conditions and circumstances of their growth, development and displacement’ [

6] (p. 8): in short, a genealogy. To assert that something might be ‘valuable in itself’ or ‘valuable for all’ is to languish in what Gilles Deleuze calls the ‘

indifferent element’ [

7] (p. 2), a position which Nietzsche’s value critique rejects. Whilst the harmonious vision yielded by Hellenic spiritual exercises may seem ideal, nothing is incontestably ‘given’ to the genealogist. Contentiously, Nietzsche argues that no one has ever doubted the fact that the ‘good man’ is of greater worth than the ‘evil man’ in the sense of his ‘usefulness in promoting the progress of human

existence’ [

6] (p. 8). Potentially, he has Socrates in his sights when he hazards the prospect that a ‘symptom of regression’ might be at work in the good man, ‘likewise a danger, a temptation, a poison, a narcotic, by means of which the present were living

at the expense of the future’ [

6] (p. 8). As a kind of ‘cultural physician’ [

5] (p. 69); [

8] (p. 35). Nietzsche proposes to diagnose the health of art and philosophy, challenging the commonplace that what is ‘more comfortable’ and ‘less dangerous’ is unquestionably a sign of flourishing [

6] (p. 8).

As a physician of culture, Nietzsche shares with Hadot a profound interest in philosophical therapeutics but he asks more exacting questions about the ‘liberation’ that the ancients prized so highly. Whilst paying tribute to Socrates as a man of courage and wisdom, Nietzsche interprets his celebrated last words as evidence that ‘Socrates

suffered life!’ [

8] (Aph. 340, p. 272). Allegedly, at the moment of his death, Socrates asked that an offering be made to Asclepius, the god of healing. With this ‘veiled, gruesome, pious and blasphemous’ utterance, Socrates betrays his judgment that ‘

life is a disease’ [

8] (Aph. 340, p. 272). All his life long, Nietzsche contends, Socrates concealed his dissatisfactions under the veil of living the ‘good life’. What Socrates reveres is not this earthly existence, but something quite the contrary: otherworldly freedom from its woes.

Nietzsche’s interrogation of values is provocative, challenging, and often audacious in its claims. Nevertheless, what his genealogical critique brings into relief is the fact that values have a history and their meanings are not self-evident, however incontrovertible they might appear. Not even the ‘good life’ of Socrates is exempt from interrogation. Most importantly, the values that are attributed to such individuals are regarded by Nietzsche as indicative of broader, transpersonal forces. According to Horst Hutter and Eli Friedland, Nietzsche held that ‘beliefs, behaviors, ideals and patterns of striving’ are not things for which individuals or even cultures are responsible; ‘they are symptoms of what an individual or a culture is’ [

9] (p. 1). As Deleuze remarks, values ‘presuppose evaluations’, perspectives from which their own value is derived [

7] (p. 1). In this context, ‘life’ is understood in the widest possible sense as an impersonal economy of embodied perspectives or what Nietzsche calls ‘will to power’, the provenance of which it is the role of the cultural physician to interpret or ‘diagnose’.

Seen through this lens, Socrates’ last words are indicative of life-negating values deeply embedded in the ‘body’ of a culture. According to Nietzsche, in cultures dominated by Platonic-Christian ideals and beliefs, physiological decadence has gained ascendancy, and a ‘depleted will to power has been enshrined as the highest type’ [

10] (p. 45). Andrea Rehberg writes that ‘in Nietzsche’s oeuvre, will to power and physiology belong together as virtual synonyms for each other’ insofar as physio-psychological drives vie with one another in their formation of bodies [

10] (p. 39). The question in the interpretation of any phenomenon is strictly genealogical inasmuch as it asks which forces or perspectives have triumphed and which have been subdued. Extending the discourse of therapeutics into a discussion of Romanticism, Nietzsche declares that ‘Every art, every philosophy may be viewed as a remedy and an aid in the service of growing and struggling life: they always presuppose suffering and sufferers’ [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 328). He embellishes the point by proposing that there are two kinds of sufferers, those who suffer from ‘

the over-fullness of life’ and those who suffer from the ‘

impoverishment of life’ [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 328). These bestowing or exhausted types are to be read symptomatically: ‘Regarding all aesthetic values I now avail myself of this main distinction: I ask in every instance, “is it hunger or superabundance that has here become creative?” [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 329). According to this criterion, art and philosophy spring from either surfeit (‘an excess of procreating fertilizing energies that can still turn any desert into lush farmland’) or from lack (‘a certain warm narrowness that keeps away fear and encloses one in optimistic horizons’ [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 328). In Nietzsche’s estimation, ecstatic ‘Dionysian’ art and tragic insight are the progeny of the first whereas Romanticism and Epicurean wisdom are deemed to stem from the second [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 329).

This latter point is significant because, despite a more positive reading of Epicureanism in his earlier philosophy, Nietzsche comes to see the mildness, calmness, and peacefulness central to its therapeutic regime as the desiderata of the sickly and the weak. By contrast, he declares that the one who is ‘richest in the fullness of life’ can ‘afford the sight of the terrible and questionable’ [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 328). In context, dark passions and destructive desires

might be read as indicative of luxury—the immense vitality of a culture with the strength to think against itself. By contrast, and however counterintuitive, release from discomfort

might be seen as a sign of weakening, declining life, or defeated spirits, preserving themselves against the fear of the unknown.

Whilst any such interpretation of values is open to challenge, the merit of value critique lies in prompting us to submit the concepts we take for granted to genealogical scrutiny. Following Nietzsche, we are encouraged to ask about the conditions within which values deployed in contemporary discourses have come into being. Are they symptomatic of plentitude or poverty? Inflecting Hadot’s account of philosophy with Nietzsche’s genealogy gives us a way of considering the value of art for life beyond any culturally dominant perspective. This is particularly illuminating when considering current concepts of creativity and ‘creative health’ within the prevailing discourses in which they are inscribed.

4. Creativity in a Contemporary Context

As Thomas Osbourne has observed, the ‘aspiration to be creative seems today to be more or less compulsory in an increasing number of areas of life’ [

11] (p. 507). Whether in the sphere of education, media, management, or the economy, ‘the values of creativity have taken on the force of a moral agenda’ [

11] (p. 507). Not only is creativity ‘the highest achievable good’ in a contemporary, Western context, but it is actually a kind of ‘moral imperative’ [

11] (p. 508). According to Yuriko Saito, in ‘workaday environments’, such as business, industry, and daily organizational life, we are increasingly encouraged to experience aspects of our lives ‘from an artistic viewpoint’, a practice that has been dubbed ‘artification’ [

12]. The neologism ‘artification’ refers to the act of taking influences from artistic ways of thinking and acting into non-artistic domains on the grounds that ‘this creativity should be made use of elsewhere’ [

13]. Advocates of artification commend the value of a ‘creative’ way of thinking that breaks away from traditional ‘linear and goal-directed planning, controlled order, stability, continuity, rationality, measurability, and predictability’ [

12]. It is said by such advocates that in order to keep up with the accelerated pace of life in today’s changing world, it ‘behooves businesses and organizations to incorporate artistic skill’ into their ways of working rather than conduct ‘business as usual, with incremental modifications’ [

12].

In contemplating how creativity is appealed to most commonly in these ‘artified’ arenas, we would do well to adopt the role of Nietzsche’s cultural physician, submitting the ‘symptoms’ of the age to diagnostic evaluation. An appropriate opportunity is provided by Reinhard G. Mueller in his essay, Nietzsche’s Art of Living in the United States Today (2023), in which he proposes that Nietzsche’s art of living is ‘particularly relevant’ in our ‘multi-perspectival, fast-paced, and uncertain’ world [

14] (p. 263). Within the context of global capitalism, Mueller declares that people are compelled ‘to adapt and grow in an ever-faster and ever-more complex economic environment’ [

14] (p. 264). With this in mind, he suggests that a ‘contemporary art of living needs to find its way with the guiding values of today’ which, following the work of Werner Stegmaier, he identifies as ‘innovation, creativity, efficiency, mobility, flexibility, resilience, and an appetite for risk’ [

14] (p. 264). Values such as ‘innovation’ and ‘creativity’ head a list of qualities which, as previously noted, are increasingly celebrated in the business world. In fact, Mueller writes with particular interest about what he sees as ‘the widespread adoption of Nietzsche’s notion of self-overcoming and artistic self-design in entrepreneurship and individual’s lives’ [

14] (p. 263), adding that Nietzsche’s notion of ‘permanent individual self-transformation’ ‘is popular in everyday life today, especially among younger generations, whose individual future tends to be more open’ [

14] (p. 266). He further observes that Nietzsche’s ideas ‘are at the heart of the “personal development” or “personal growth” industry, which eclectically combines various therapeutic models’ [

14] (p. 272). By way of an example, he cites a ‘commercial “success coach”’ whose services deploy ‘many ideas of Nietzsche’s notion of an art of living’ [

14] (p. 272). In sum, from this ‘artified’ point of view, embodying Nietzsche’s idea that our life is a ‘work of art’ [

5] (p. 109) means embracing the uncertainties of the modern world and learning to ‘live dangerously’ [

14] (p. 266).

It will not escape notice that Mueller’s conception of Nietzsche’s art of living is underpinned by neoliberal thinking. Most notably, the ‘guiding values’ of the day are taken as given and are not subjected to critique, a remarkable irony in the context of a discussion of Nietzsche. In the scenario Mueller presents, we are self-interested agents entreated to yield to precarious market conditions by artistically ‘curating’ all aspects of our work and leisure. What goes unremarked here is that the good life has become a commodity and the philosopher a consumer. With the art of living defined in such ‘worldly’ terms, its pursuit via commercial life coaching is likely to inhibit rather than enable philosophical reflection. Despite the heroic rhetoric of embracing the unknown, this kind of ‘creativity’ is born of a need to conform to the guiding values of the dominant ideology, rather than from an excess of inventive energies. Read symptomatically in terms of Nietzschean genealogy, it is ‘hunger’ rather than ‘superabundance’ that has become creative here.

This diagnosis finds support in the work of Oli Mould who argues that contemporary capitalism has commandeered the radical language of ‘creativity’ to carry on ‘producing the status quo’ [

15] (p. 3). As a value, creativity is highly prized in business culture wherein economic growth is an uncontested good that governs all the terms of debate. The imperative is to perform successfully within these parameters, not to question the system as such. Paradoxically, then, creativity is a value that may make us complicit with what Osbourne calls ‘the most conservative of norms’: individualism, performativity, and productiveness and ‘the compulsory valorization of the putatively new’ [

11] (p. 508). Far from taking risks, to be creative within capitalism is to produce more of the same, the triumph of minimal variation, the manufacture of products and producers which ‘very closely resemble those that are already successful’ [

16] (p. 83). The ‘provocative value of artified practice’ resides only in raising questions about an existing business strategy, its worth gauged simply by ‘its contribution to the organization’s success’ [

12]. As Ossi Naukkarinen observes, creativity within the context of ‘business artification’ may mean developing strategies that are more emotionally rewarding for employees but the bottom line is ‘not to shake the fundamental foundations and question, for example, whether economic profit is a primary value’ [

13].

As Justin O’Connor has argued, ‘one of the devastating consequences of the neoliberal epoch has been the inability to answer questions of value which fall outside of market mechanisms’ [

17] (p. 28). In a marketized world, people are driven by values of ‘self-optimization’ and are enjoined to become ‘entrepreneurs of their own selves’ [

18] (p. viii). Indeed, Mould maintains that ‘being creative’ today means seeing the world around you as ‘a resource to fuel your inner entrepreneur’ [

15] (p. 10). This is far removed from the poetic perception of the world

qua world which Hadot suggests delivers us from an instrumental orientation to existence. On the contrary, the creative industry advocates’ primary focus on ‘self-discovery through art may exacerbate a tendency toward self-absorption’ [

12]. It is essentially an outlook which emphasizes the successful performance of the individual agent, the atomistic subject, for whom the art of living is about ‘personal development’ rather than any wider sense of connection to the social whole.

A similar point might be made about wellbeing. In societies preoccupied with material gain, not only do the values of ‘self-care’ appear unquestionably ‘good’, to suggest otherwise is unthinkable. It may seem axiomatic to put ‘self-preservation first of all things’ [

19] (p. 306) but in the context of neoliberal ideology this individualism is often embraced at the expense of a broader philosophical and social vision. As Francis Fukuyama has said, ‘the nihilism that once filled Nietzsche with dread is now worn with a happy face in contemporary America’ [

19], (p. 387). Fukuyama claims that the modern human ‘becomes concerned above all for his own personal health and safety’ because it is uncontroversial and does not entail the making of moral decisions about what is better or worse for society more generally [

19] (p. 306). In sympathetic mode, Mark Fisher argues that capitalism promotes ‘a reductive, hedonic model of health which is all about “feeling and looking good”, whilst avoiding more searching questions about mental health and intellectual development’ [

16] (p. 80). In short, ‘living well’ within the context of contemporary capitalism is far removed from the ‘art of living’ bequeathed to us by the ancients.

5. Creative Health

In light of these critical reflections, how might we situate the concept of ‘creative health’ that has been developed in the UK over the last decade? In the first Full Report of the UK All Parliamentary Group on Arts, Wellbeing and Health (2017), it is stated that ‘the creative impulse is fundamental to the experience of being human’ [

20] (p. 20). The central premise of the group document is that ‘engaging with the arts has a significant part to play in improving physical and mental health and wellbeing’ [

20] (p. 20). To this end, the writers of the report affirm the belief that the arts can be enlisted to help address a number of difficult policy challenges, ranging from strengthening illness prevention to improving social care. In overview, it is asserted that: 1. the arts can help us keep well, aid our recovery, and support longer lives better lived; 2. the arts can help meet major challenges facing health and social care: aging, long-term conditions, loneliness, and mental health; and 3. the arts can help save money in the health service and social care [

20] (p. 4). The full report presents the findings of two years of research, citing persuasive evidence of improvements in health and wellbeing from engagement with the arts. Unlike the ‘hedonic model of health’ marketed as an individual lifestyle choice, ‘creative health’ derives its identity from a broad range of communal activities, often shared in community spaces as well as healthcare settings. The initial

Creative Health Inquiry Report (2017) and the follow-up

Creative Health Review (2023) contain a plethora of examples of positive creative health interventions across the life course from early years to end-of-life care, bolstered by evidence of the benefits of the policy from service users and strategic partners from across the sector. With such rich testimony, the value of art for life in the context of creative health is so strong as to be almost beyond question.

This said, since the authors of the Creative Health documents aspire to achieve change in policy and practice, there is an acknowledged instrumental imperative guiding their commitment to the value of art. Anticipating this criticism, the authors assert: ‘We have no desire to ignite another flare-up in the chronic and sterile altercation between the proponents of art for art’s sake and those who justify public intervention at least in part on the basis that the arts confer benefits on society’ [

20] (p. 5). Perhaps somewhat confusingly, they go on to declare commitment to ‘the validity of art itself’ in leading to better health and wellbeing, citing Samuel Johnson’s belief that the end of literature is ‘to enable the reader better to enjoy life, or better to endure it’ [

20] (p. 5). Commenting on the report, Kate Phillips writes that ‘The tension between intrinsic and instrumental value remains central to the arts and health agenda’ [

21] (p. 22), her recommendation being that more research is conducted to yield robust, ‘objective’ data that might advance the debate. As multiple authors on this topic concur, the ‘debate between, roughly speaking, pleasure and purpose, is longstanding’ [

22] (p. 198) and since ‘different forms of art affect well-being in different ways’ [

23] it is a major challenge to determine whether ‘individuals with higher well-being are simply more likely to participate in the arts or if the activity itself leads to higher levels of well-being’ [

22] (p. 194). However, rather than pondering issues of intrinsic and instrumental value, a Nietzschean-inspired genealogical critique would query whether this is the sort of deliberation that should occupy us. For Nietzsche, ‘genealogy is as opposed to absolute values as it is to relative or utilitarian ones’ [

7] (p. 2). It is

the value of these values that is contested in any given instance. In place of facts, the genealogist proposes interpretations of ‘facts’. The question concerning the value of creativity is a diagnostic one—whether a phenomenon is symptomatic of plentitude or poverty. In the context of creative health, this entails a diagnosis of the ‘conditions’ of cultural production rather than analysis of cultural ‘products’ as such. Seen from this perspective, it is the dominant ideological framework within which creative health is situated which is deserving of our scrutiny.

According to Andrea Rehberg, where life-depleting ideals have gained ascendancy in a culture, the capacity to enrich life has ‘almost been bred out’ [

10] (p. 45). Even within the context of creative health, the conservative norms of neoliberalism are much in evidence. Since public services, like businesses, have to prove their worth in order to satisfy government agencies and other stakeholders that continued funding is valid, policy advocates are constrained in the kinds of art that they can endorse. Without denying that arts allow access to emotions of anguish, crisis, and pain, the authors of the

Creative Health Inquiry Report (2017) identify ‘creativity’ as ‘a means of empowerment that can help us to face our problems or be distracted from them’ [

20] (p. 20). For this reason, the so-called ‘lived experience expert’ is frequently called upon to endorse the value of creative health interventions by means of a compelling ‘recovery narrative’. This is a dominant genre within mainstream mental health services which functions to normalize a particular kind of recovery ‘journey’. As Angela Woods et. al. have shown, the ‘hope’ and ‘resilience’ expressed within this formulaic account are ‘so often regarded as self-evidently desirable’ that there is little space for a critical discussion of their potentially negative impacts [

24] (p. 237). It is by means of this narrative that particular kinds of market values are reinforced, including ‘entrepreneurial’ future-orientated, ‘goal-focused modes of subjectivity’, tied to ‘imperatives of economic participation’ and productivity [

24] (p. 237). The ‘compulsory positivity of the Recovery Narrative’ [

24] (p. 222) means that problematic, ambiguous, or ‘unsuccessful’ experiences need to be edited out of the story and hence airbrushed out of history. Most insidiously, such recovery narratives serve to abstract the individual from their immediate social network and the wider social context of their suffering, depoliticizing their experiences and obscuring their broader determinants.

This is not to suggest that the proponents of Creative Health are inattentive to the social determinants of health. On the contrary, they are clearly highlighted in the 2017 Report, and in the

Creative Health Review published in 2023 they are accorded still greater prominence. Nevertheless, following Nietzsche, we might ask whether it is ‘hunger’ or ‘superabundance’ which drives the rehabilitation narratives in current policy. The muffling of social dissent within the recovery script recalls Nietzsche’s characterization of ‘impoverished life’ which bespeaks ‘a certain warm narrowness that keeps away fear and encloses one in optimistic horizons’ [

8] (Aph. 370, p. 328). Art-making that is illegible as personal gain or as the soothing of psychological ills is not captured in these particular narratives. Potentially more concerning is the risk that this model of art as a panacea for the suffering individual becomes the default understanding of the benefit of creative health.

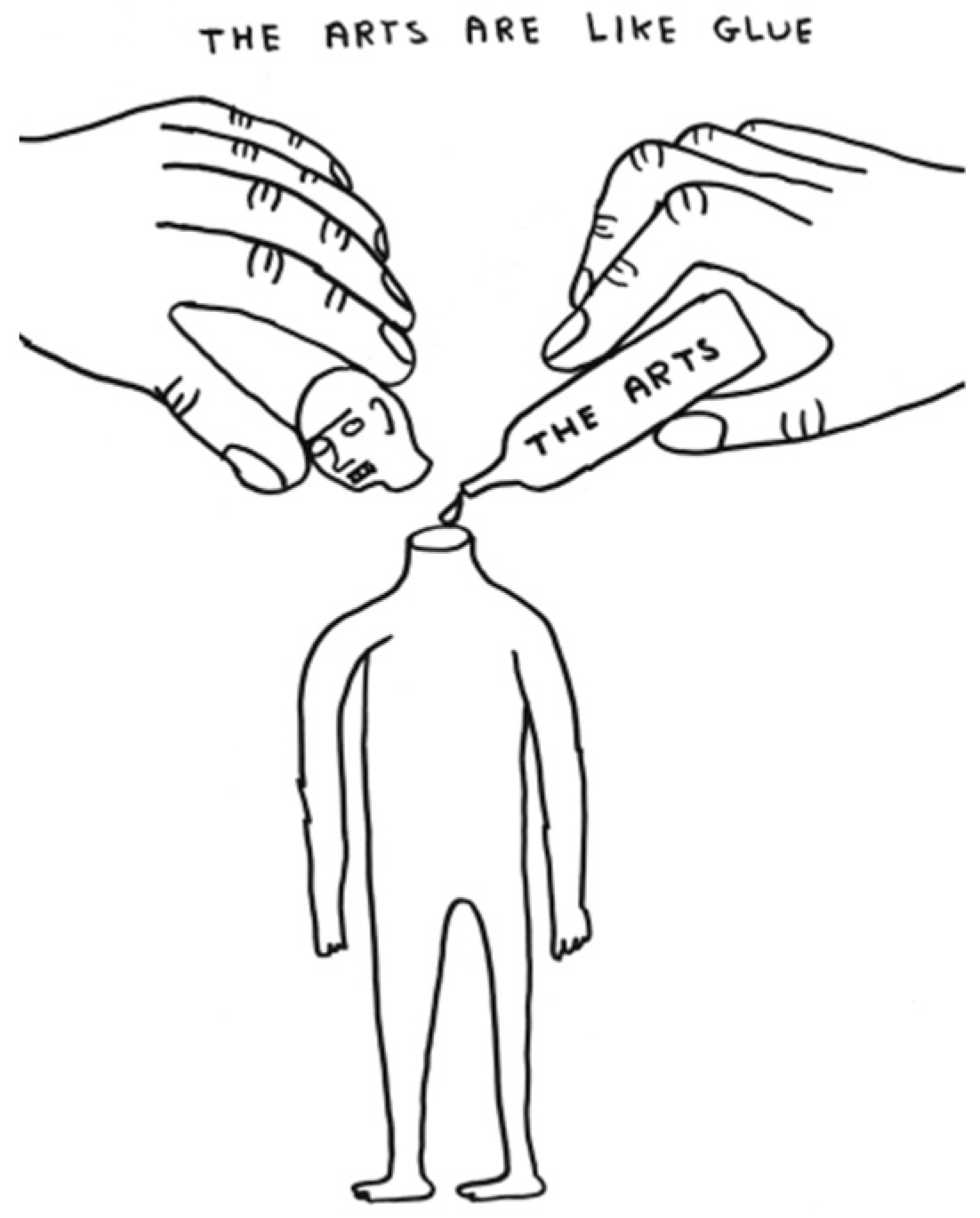

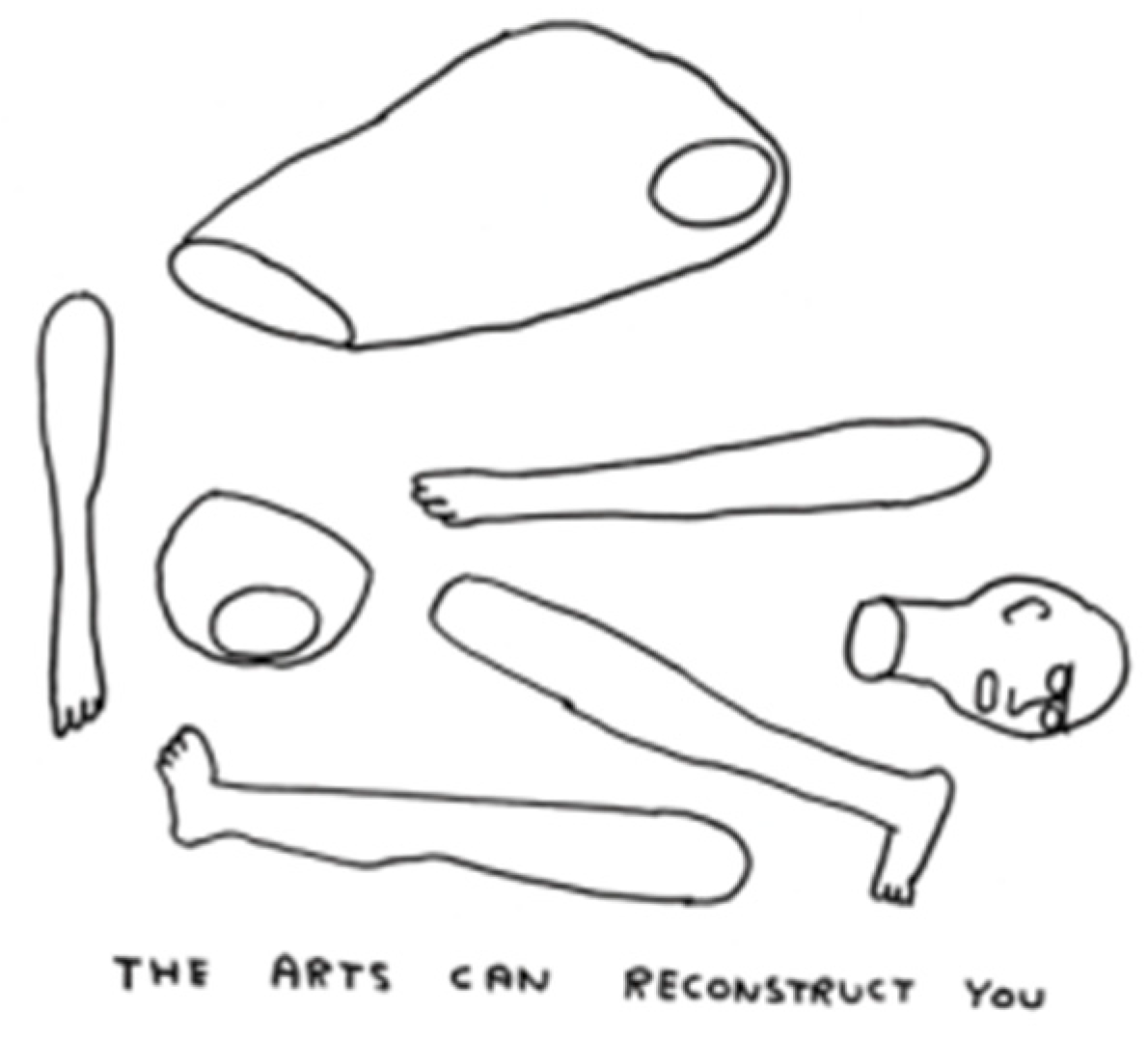

Two line work drawings (

Figure 1 and

Figure 2) used to illustrate the

Creative Health Short Report (2017) [

25] serve to confirm the recovery narrative as a technique of subjectification. The sentiment that art can support ‘broken people’ is worthy but what goes unasked is how they fell apart in the first place.

In the ‘aesthetics of repairing’, Mădălina Diaconu comments, ‘creativity appears to be subordinated to continuity’, to accommodating and adapting, rather than to producing something new [

26] (p. 288). The danger of a conservative wellbeing agenda is that it elides the difference between the social and political conditions that produce damaged people and the damaged people as ‘subjects’ in need of repair. If art has a therapeutic power, it must extend beyond merely restoring a given order.

6. The Art of Living Today

In light of these critical reflections on creativity and living well, the question remains as to whether it is possible to see the value of art for life today outside of neoliberal ideals. It is not surprising that policy recommendations concerning creative arts should be couched in the language of market values since, as Mark Fisher has said, it is increasingly difficult to envisage any alternative economic and political system beyond capitalism [

16]. However, to fully appreciate the value of art for life, it is imperative to think beyond the functional role that is accorded to art within the context of current social policy. This is difficult to do because the ‘culture-as-industry’ model undermines the case for ‘any concerted policy for art and culture outside of its instrumental value’ [

17] (p. 5). Business ideology has such a grip on perceptions of what is normal that it seems absurd to question the (apparently self-evident) value of economic growth or the positivity of the recovery narrative. Whilst creative practice in its myriad forms has the potential to ‘critique normalising and centralising forces’ [

27] (p. 469), in public policy the role bequeathed to art is to reinforce rather than to contest the status quo.

How might we see the value of art for life beyond our current way of doing so? Let us recall that both Hadot and Nietzsche intimate that art has the power to render the world visible and knowable beyond culturally dominant modes of thinking. As previously discussed, for Hadot, the therapeutic practices of the ancients compel intense examination of human freedom. Emulating Socrates, the philosopher in pursuit of the good life will step back from conventional values and will speak candidly, having no regard for acquiring wealth or supporting the views of the powerful. For the critical thinker, there is no imperative to align one’s outlook with the ‘guiding values’ of the day. On the contrary, to distance oneself from the mantra of ‘efficiency’, ‘flexibility’, and ‘resilience’ in our market-orientated times may be salutary. Moreover, for Hadot, it is the experience of art which makes possible this alternative way of seeing in the modern age. He suggests that spiritual exercises from Hellenic and Roman philosophy promote a state of being which is akin to an aesthetic perception of existence. In attending closely to existence as such, one surrenders a narrow individualist perspective, with its goal-orientated projects and utile concerns. Liberated from selfhood, one feels part of the burgeoning life of things, both part of the ‘cosmic whole’ and the ‘human community’ [

2] (p. 283).

Translating these insights into a contemporary idiom, we would do well to turn our attention to the role that participatory, community arts play in engendering the conditions for this liberation. Arguably, a sense of transpersonal connection is experienced most powerfully when artistic practices are shared in collective activities and communal spaces, as is the norm in many contemporary creative health interventions. Peter Goldie maintains that ‘artistic activity affords, in a special way, a certain kind of emotional sharing that binds us together with other human beings’ [

28] (p. 179). Echoing this sentiment, Yuriko Saito highlights the fact that our aesthetic life includes ‘our social interactions with other people’ [

29] (p. 23). For Saito, ‘to live a good life in a community’ it is imperative to ‘move away from today’s neoliberal ideology which privileges personal autonomy, self-reliance, and individual responsibility’ [

26] (p. 302). Standing back from worldly concerns facilitates a more profound sense of our presence in the world and our connection to all things. Wellbeing in this context is achieved socially rather than singularly and is more a collective phenomenon than a personal one.

Through this aesthetic sharing, philosophical questions about the good life may well come to the surface. A wide array of collective art practices affords a precious opportunity to discuss values for life and what it means to live well. Because project evaluators seek evidence that publically funded creative activities are beneficial, participants are constantly encouraged to be reflective about the ‘impacts’ of their experience of art. For this reason, there is ample opportunity to contemplate deeply, to adopt a philosophical stance on the ‘value’ of contemporary ‘values’, and to exceed the limitations of the recovery narrative. Not only do community projects make possible a space for people to live examined lives, but they also grant an ‘intimate awareness of the

permanent possibility of emotional sharing’ [

28] (p. 193). This has the potential to make an inestimable existential difference. As Peter Goldie says, ‘engaging in artistic activity can deepen our self-understanding and change our life’ [

28] (p. 192).

It will be recalled that in the context of the intrinsic value versus instrumental value of art debate, the authors of the

Creative Health Inquiry Report (2017) invoke Samuel Johnson’s designation of literature as helping us to either enjoy life or to endure it. However, there is a third option, the possibility of transforming life altogether. At their best, creative health initiatives make just this kind of fundamental change. Often the most enduring interventions are those which seek to reconnect individuals with one another and with the deep life of the community. A good example is provided by the Bolton ‘Cotton Queens’ Group, established in 2019 through a partnership between the social housing provider ‘Bolton at Home’, Bolton City of Sanctuary and the University of Greater Manchester, UK (then the University of Bolton). Initially, Cotton Queens was designed as a twelve-month arts and heritage project to reduce social isolation of women aged over 50. Using archival research and creative writing, project participants explored the lives of women who worked in the local cotton mills in the 1930s, drawing connections between their previously untold stories and their own untold experiences of work, home, and leisure. What was distinctive about the Cotton Queens project was its perceived value as an opportunity to create new narratives of belonging as well as to foster self-understanding, as evidenced by the participants’ enthusiasm for its continuation (

https://bolton.cityofsanctuary.org/cotton-queens-project-2023, accessed on 25 May 2025). What started out as a stand-alone project developed in to an ongoing social and creative group that is still active five years later. As Kevin Melchionne has argued, ‘those features of our culture which encourage participation’ are the most valuable [

22] (p. 208). What matters in the framework of wellbeing is ‘the quality of the engagement with art as an activity, that is, as a part of one’s life’ [

22] (p. 205). It is worth remarking that a few participants with identified wellbeing needs entered the Cotton Queens project having developed an interest in performance and local literary history through a prior university project. This reinforces Melchionne’s essential premise that ‘art supports well-being when it is an ongoing activity and less so when it is only the source of occasional aesthetic experience’ [

22] (p. 197). Most importantly, it attests to the transformative power of art, a health-creating way of being in the world that shares a lineage with the ancients.

A second significant example of ‘creative health’ is the Bolton Mass Observation ‘Diary Day’ (2024). Members of the local Bolton community were invited to record the full details of their day on 12 May 2024 for upload to the Mass Observation archive currently held at the University of Sussex. Although never envisaged as a ‘wellbeing’ initiative, many of the diary writers sought to pass on to their future readers the wisdom of their ‘art of living’. Individual moments of savoring the small things in life—seldom acknowledged as relevant aspects of reality—were described with remarkable gratitude. Indeed, beyond interesting sociological detail about how the respondents live, ‘the Diary Day initiative supplied unexpected insights in to how to live well’ [

30] (p. 13). This accords with the Creative Health understanding of the arts as a ‘shorthand for everyday human creativity’ rather than some elevated cultural activity [

20] (p. 19). It also supports Melchionne’s proposition that the concept of aesthetic pursuits be extended to incorporate less highly visible activities including ‘everyday practices involving food, wardrobe, dwelling, and going out (running errands or commuting) that largely escape critical discussion or mass distribution’ [

22] (p. 207). From the vantage point of these modest projects, it is possible to relish life aesthetically, beyond the demands of utility and the familiar framework of immediate need.

This is not to insist that there is any one formula for the good life. Yuriko Saito reminds us to ‘consider Friedrich Nietzsche’s view on creating a work of art out of life’ and his notion of giving style to one’s character [

12]. Musing on the merits of this, she speculates that wholesale ‘artification’ of life ‘may not necessarily lead to maintenance of the status quo of a society’ but ‘there is no guarantee that artification will lead to improvement’ either [

12]. Perhaps more than anything, her point underscores the need to question the value of values, to ask what motivates and sustains our aesthetic activities, rather than to assume that any given version of living well is immune to critique.