Abstract

Following philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s unique phenomenology of embodiment and his understanding of three-dimensional space as existential rather than geometric, the article claims that despite sophisticated algorithmic imaging tools, architectural space as a space of meaningful experience does not subject itself to both two-dimensional and three-dimensional representations and simulations. Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenology is instrumental in helping identify a “blind spot” in contemporary architecture design process. Our experience of built space is always far more saturated (with regard both to the input of the senses and our cultural and personal background) than any sophisticated tool of representation. This paper draws a direct link between the invention of linear perspective and the use of digital three-dimensional visualization and the popular opinion that these are reliable tools with which to create architecture. A phenomenological analysis of Beaubourg Square in Paris serves as a case study that reveals the basic difference between experiencing space from the point of view of the actual subjective body who is present in space and experiencing designed space by gazing at its representation on a two-dimensional screen. Relying more and more on computation in architectural design leads to a rational mathematical conception of architectural space, whereas the human body as the actual experiencing presence of this space is overlooked. This article claims that in cases of great architecture, such as Beaubourg Square in Paris, the lived-experience of the built space is also the experience of bodily presence, which is a unique mode of existential meaning, which cannot be simulated or represented.

1. Introduction

Maurice Merleau-Ponty (1908–1961), is considered as one of the most important existential phenomenologists and philosophers of his generation. His important project, Phenomenology of Perception (1945), places the body at the focus of perception, emphasizing consciousness as embodied consciousness. For Merleau-Ponty, sensory perception is not an act in itself but the background, the assumption of any perceptive act as judgment, imagination, or description [1] (p. xi, p. 13). Sensory perception is the immediate givenness of the world, which appears to us as having regularity, patterns, and varied meaning contexts [2] (p. 44).

Merleau-Ponty’s unique influence on the field of architecture stems from his emphasis on sensory perception and embodiment as preceding all intentional acts, all claims for knowledge and understanding. His conceptions of lived-space (rather than geometrical space), the visual field, depth, and of course embodiment, have influenced renowned architects such as Steven Holl and Peter Zumthor and researchers such as Alberto Perez-Gomez, Juhani Pallasmaa, and David Seamon. The book Space, Place and Architecture is a collection of essays dedicated to these subjects in the work of Merleau-Ponty1.

Still, phenomenological approaches, including Merleau-Ponty’s, to architecture are considered marginal within the field of architecture, both as a discipline and even more so as a practical profession. This is partly due to the inaccessibility of phenomenological thinking to architects, but there is another important reason: our contemporary culture, increasingly dominated by algorithms and big data, gives precedence to the measurable and the visible, and the architectural field follows suit. Practitioners and researchers in architecture are enchanted with the new design and imaging capabilities of complex architectural forms that are available today digitally to architects and designers, capabilities that are evolving almost daily, especially with the inception of artificial intelligence tools.

These digital tools are considered reliable for evaluating and show-casing a project, much more reliable than two-dimensional architectural images (such as a plan, section, or perspective, be it digital on a screen or printed on paper) for simulating three-dimensional space. Moreover, the rapid development of three-dimensional immersive digital simulations, such as current technologies of virtual reality and augmented reality, are steadily getting better and are considered by many to be in the near future the definitive answer to the representational gap in architecture [7,8,9]. And still, all these advanced and sophisticated digital tools are code-based and data-based; thus, as we shall show, they cannot compute abstract or sensual spatial experiences of meaning.

In this article we revisit the question of the possibility of adequate representation of architectural lived-space within the design process, focusing on a specific aspect: the link between spatial meaning and embodied presence. We would like to return to Merleau-Ponty in order to rehabilitate the primordial importance of architectural space not only in the sense that governed modernist architecture of early twentieth century, as the epitome of the aesthetic experience of architecture, but more fundamentally as a potential source of spatial existential meaning2. A rehabilitation of the notion of lived-space and embodied perception of the environment is necessary and can prove to be beneficial to our habitat, not only in the sense of functionality and aesthetics but in the notion that architecture can create a space that draws our attention not only to it but to ourselves as bodies present in it. We consider embodiment in the architectural context as experiencing being present in space as an experience of meaning.

The first section discusses the importance of linear (geometric) perspective in the profession of architecture in the past and present pointing to its firm hold on architects. The second section briefly introduces the perception of the body within the architectural tradition and contrasts it with the phenomenology of perception of philosopher Maurice Merleau-Ponty, focusing on his notion of the intertwining of human embodied consciousness and the existential and cultural space surrounding it, as the ground for any bestowal of meaning. The third section reviews some of the current digital three-dimensional representation and simulation tools with regard to the possibility of creating that intertwining, that meaningful architectural space within a digital simulation. The final section is a phenomenological descriptive analysis of Beaubourg Square in Paris as a case study for the way our physical embodied presence within an architectural space can bear ontological and existential meanings.

2. Linear Perspective and the Despotic Gaze

In his famous treatise, Architecture as Space (1974) [12], architect and researcher Bruno Zevi (1918–2000) re-examined the history of architecture through the concept of architectural space. Zevi argued that as long as the concept of space is not perceived as the fundamental principle of the architectural action, the history of architecture cannot be written [12] (p. 22). He explained that ignoring the concept of space as a fundamental concept in architecture is a result of the difficulty in defining accurately “the nature and character of the architectural space”. According to Zevi, the accepted ways of representing architectural structures in books on the history of architecture—plans, facades, and photographs—leave the space as an absent or a missing element [12] (p. 45).

By considering photographs inadequate for spatial representation, Zevi in effect suggests that perspective imaging on two-dimensional planes is incapable of communicating the experience of three-dimensional spaces. Before Zevi, it was the famous art historian, Erwin Panofsky, who considered linear perspective as a symbolic form, rather than an accurate representation of space. But before we lay out our arguments, we will discuss a few key notes on the invention of linear perspective, its principles, and its application in the field of architecture.

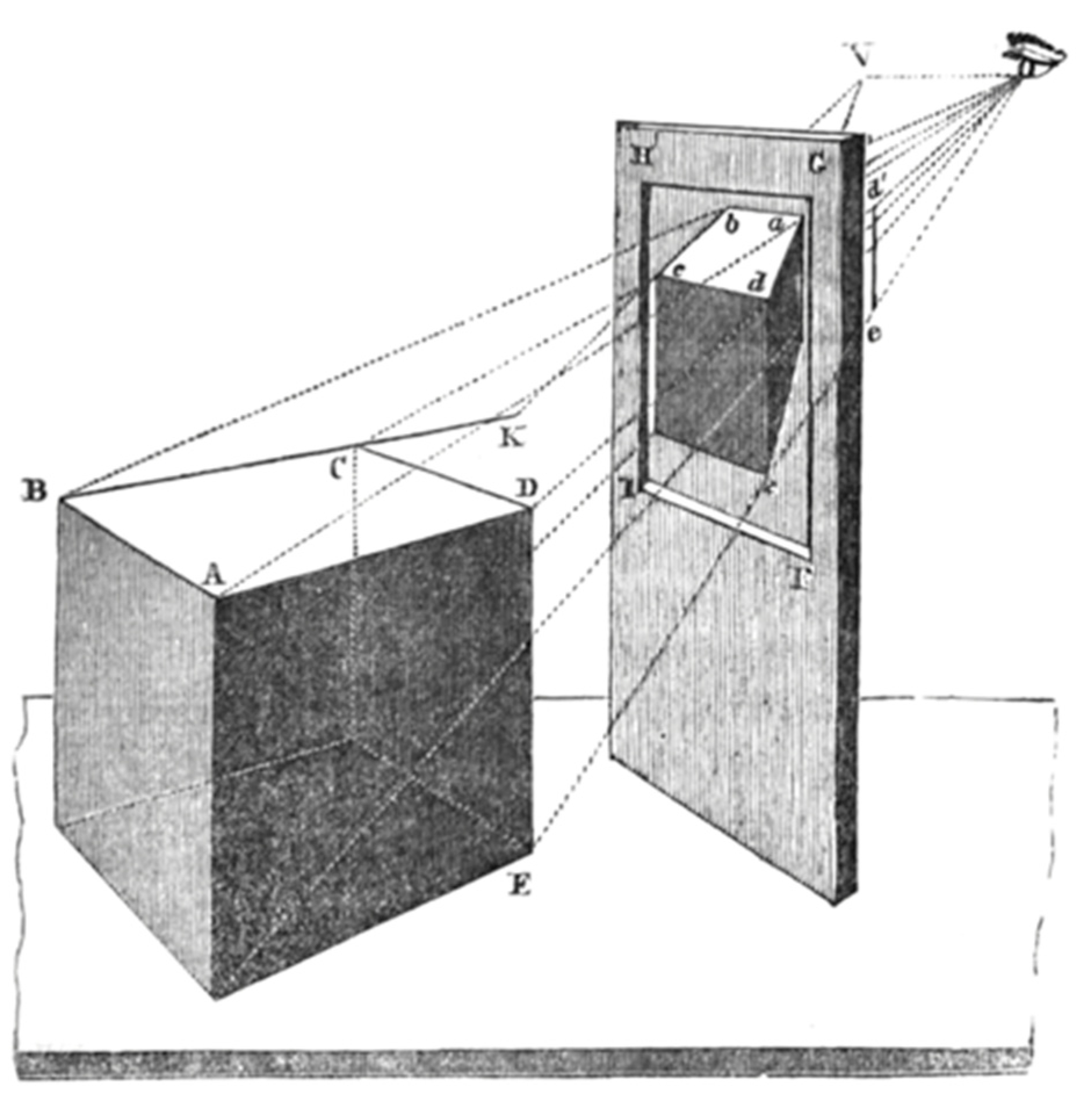

In his treatise On Painting (1435) [13], Leon Battista Alberti details his method for drawing a perspective by creating a vertical plane that seems to dissect the cone of vision at a certain point (Figure 1) [13]. In order to compose the linear perspective, one should determine the point of view, the horizon line, and the vanishing point where all the orthogonal lines converge into each other and into the horizontal plane of the ground. Some have likened the invention of perspective to a divine revelation for Renaissance people, a revelation that appears in geometric order, which as if by magic enables three-dimensional reality to appear as such on a two-dimensional plane [14] (p. 31). It is no wonder that Renaissance people were amazed and even enchanted by the wonders of perspective. Suddenly, the world is “within reach”, with a stroke of a pen3.

Figure 1.

This diagram, following Alberti’s method, shows how the image plane dissects the cone of view (From Brook Taylor’s 1715 book, Principles of Linear Perspective [16] (p. 9)).

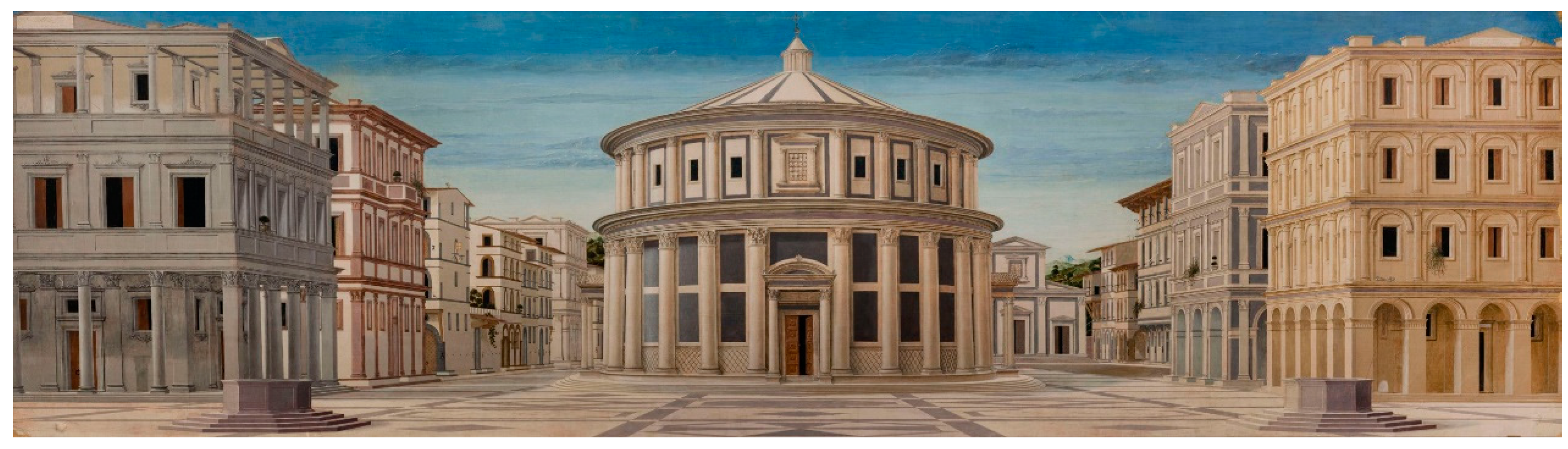

The painting Citta Ideale (Figure 2) is an explicit example of the use of one-point perspective, in which all the orthogonal lines converge into one vanishing point located (as it were) in the center of the image plane. The one-point perspective emphasizes the depth dimension by making all the objects more “distant” from the imagined image plane, so they are proportionally smaller. The only correct dimensions, which match the dimensions of the buildings if they existed in reality (at an agreed scale), are those we see at the front of the painting, in the length and height axes. The dimensions of the buildings along the depth axis are foreshortened. This means that in order to obtain a two-dimensional picture that we perceive as a realistic description of a three-dimensional space, the objects are drawn in a “distorted” way, simulating the way we perceive objects in three-dimensional space through our sense of vision.

Figure 2.

Citta Ideale (The Ideal City), Italy, late fifteenth century, unknown artist.

Yet, if we examine the discovery of linear perspective in its historical context, as a tool of the painter, a significant difference emerges: unlike the art of painting, in which the artwork is its own end, in the field of architecture, the sketches, including the perspective images, are a means rather than the end. Linear perspective enabled artists from the Renaissance up to the twentieth century to achieve a realistic and persuasive representation of the world on canvas, but in contrast with the art of painting, in architecture, perspective serves completely different purposes: the perspectival drawing enabled architects to examine the shape of the buildings they were designing even before they were built; in other words, they functioned as a designing tool, as a representation of a possible reality that had yet to be realized. The second purpose of architectural perspective is as a simulation intended to reassure the customer about the planning before it is approved for construction4. Linear perspective served as a powerful tool for effective communication between all the “players” involved in the design process, from planning to construction. Plans and facades are perceived by architects as partial representations of their design, unlike linear perspective and even the architectural section, which are perceived by architects as faithfully representing three-dimensional spaces.

The inception of the theoretical discourse around linear perspective is attributed to art historian Erwin Panofsky. In his well-known treatise, Perspective as Symbolic Form (1927) [17], which relies on the philosophy of Ernst Cassirer [18], Panofsky argues that linear perspective, the geometric method of representing a three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional plane, is a cultural, symbolic construct and should not be considered the exclusive means of representing three-dimensional space or as an absolute representation of actual reality5. Panofsky viewed linear perspective as a symbolic form, since it is actually a geometric, mathematical abstraction of the way we perceive space through the sense of vision. As Brooks’s illustration shows, perspective appears to a single, disembodied eye looking at the world outside itself.

Linear perspective does not take into account that we have two eyes, that the surface of our eyes is convex, and that our vision is not equally sharp throughout the field of vision [17] (p. 30). The horizon obtained in the field of vision is also not a real entity but the outcome of our mode of vision. Consciousness chooses to cancel distortions arising in the field of vision also through the sense of touch [17] (p. 31), and thus our act of seeing is in practice subjective and interpretative. For these reasons, Panofsky considered perspective not merely a technical, geometric, “neutral” invention but rather a product shaped by culture. Another significant difference is that we are bodies in constant motion. Our mode of perception is cumulative rather than static.

The Latin meaning of the term perspective is “to see through”, and Panofsky emphasizes that the Renaissance artists perceived perspective painting as akin to looking through a “window” into spatial reality [17] (p. 27). While this conceptualization holds true for paintings displayed on museum walls, it poses challenges when representing architectural spaces prior to their construction. Even in the most perfect and accurate perspective drawings, observers remain anchored outside the depicted world; they can never confuse themselves with being within the simulated space presented in such images. Consequently, linear perspective separates the act of vision from human embodiment.

3. Phenomenology of Space, Embodiment, and Perception

3.1. The Human Body in Architectural Tradition

The connection between architecture and the human body has a long history in western culture. The human body, as a creation of nature, constituted an object for direct and indirect imitation in architecture and sculpture already in ancient cultures such as Pharaonic Egypt and Ancient Greece. The Caryatids in the porch of the Erechtheum at the Acropolis are stone columns sculpted as female figures, with proportions similar to those of an upright human body [19] (p. 75)6. Mimesis is not limited to the sculpting of human figures and their inclusion within structures: Vitruvius compared the dimensions of the human body and their required proportions with the proportions required between parts of a building and the whole building [20] (pp. 87–88)7. One of the best-known ratios of antiquity is, of course, the Golden Ratio, which was also attributed to certain organs in the human body, but this is one of many, such as the Symmetry Ratio, characterizing the human body, which became the most prominent in various architectural styles up to the twentieth century8.

The perception of the human body as a model of desirable ratios, as the Classical tradition believed, and as a model for formal imitation in the design of buildings, as John Ruskin (1818–1900) argued, remained central up to the beginning of the twentieth century [22] (104). Even Le Corbusier, who called for liberation from past styles, proposed his own system of proportions based on the human body, the Modulor, which served him in designing some of his most famous works, such as the Marseille residential building “Unité d’Habitation” (1952) and the convent of Sainte Marie de La Tourette (1957).

These examples indicate that the human body plays a central role in the way the profession of architecture and architectural styles developed throughout history. Moreover, the human body, as a model representing the regularity of creation, has a metaphysical significance. This regularity, portrayed in mathematical proportions, is what is perceived as “protecting” the architect from arbitrary design decisions, thus symbolically defending man in an unexpected and unstable world: “A guideline is a guarantee against the arbitrary” [23] (p. 75).

The research literature dealing with mimetic and symbolic links between the human body and architecture is very extensive, but the contexts of significance it discusses are mostly epistemological and one-directional: from the body to architecture. The body is the natural, divine authority, symbolically translated into an architectural form. But if we consider a different viewpoint, a phenomenological one, the human body and architectural space are connected, are intertwined, as Merleau-Ponty termed it.

3.2. Embodiment and Perception in the Philosophy of Maurice Merleau-Ponty

According to Merleau-Ponty, sensory data, even before they have been conceptualized, are already saturated with meaning. He argues that when we make contact with the world, the world is only familiar to us through our senses. The world is always the world as it is perceived by us at a particular moment and in a certain context. Following Edmund Husserl (1859–1938), the father of modern phenomenology, Merleau-Ponty believes that the world is not an object but the field of every possible thought and perception. In other words, humans already exist in the world, and only in the context of the world can they understand themselves [1] (p. xii)9. And so, the body has a double role: it is what exists in the world, and it is what mediates the world for the subject [1] (p. 273).

Merleau-Ponty emphasizes that the body employs all its senses in its contact with the world and rejects the possibility of a hierarchy between the various senses (for example, between touch and vision). The whole body, with all its senses, experiences the world immediately [1] (p. 262). Can the experience of walking down a narrow Parisian street be separated into its parts? Can we separate the smell of rain and the smell of the bakery in front of us from the sight of the wet leaves on the trees and the touch of the dark paving stones beneath our feet? These sensory components, which greatly influence the way we experience places and buildings, act on us as a system that we cannot totally classify or dismantle into its parts. Therefore, no form of documentation, whether text, photograph, or architectural simulation, can ever perfectly capture the experience.

Merleau-Ponty’s book, Phenomenology of Perception (1945), opens with a definition of phenomenology, as a philosophy for which the world always exists in advance, prior to any reflection, as a presence we cannot alienate and from which we cannot be released. He believes the purpose of phenomenology is to restore the direct, primary connection with the world [1] (p. vii). He argues that “the subject and the object are two ’moments’ of a unique structure that is presence” [1]) (p. 500). He says this in the context of the issue of time, but this is equally valid in relation to spatial presence. Presence in time always requires presence in a certain place [1] (p. xv)10.

The pre-reflective layer, perceived by the senses, is a perception of meaning, existential meaning. Our very existence in this world is already existence with meaning. Merleau-Ponty’s existentialism derives from his perception of the mode of connection of the physical consciousness to the world11. Our experience in the world is within a structure or system, which, even prior to any intentional act, already has significance and importance for us [25] (p. 183). This is our presence in the world, and the presence of the world for us. Since we are always in the world, Merleau-Ponty emphasizes, we are “condemned to meaning” [1] (p. xxii).

The element of meaning in acts of sensory perception is both existential and ontological. As Merleau-Ponty himself stated, his purpose is “to ontologically restore the sensible” [25] (p. 180); [26] (p. 167). He argues that we cannot phenomenologically discuss the Cartesian cogito in detachment from the self that exists within a body and perceives the world from a particular viewpoint at any given moment12. The body is the mode of our being in the world. The layer of reality that we conceptualize in language exists above a more basic, pre-linguistic layer. According to Merleau-Ponty, the human desire to know and understand the world through categories is the factor that distorts our understanding of the act of perception [1] (pp. 61–62). Exact science, built on absolute representations, removes the vagueness that exists in the real world as it is naturally perceived by us. These absolute representations are based on the (false) belief that we can direct our attention to only one thing through the act of perception. Merleau-Ponty writes the following:

It is necessary that the thought of science-surveying thought, thought of the object in general, be placed back in the “there is” which precedes it, back in the site, back upon the soil of the sensible world and the soil of the worked-upon world such as they are in our lives and for our bodies…[28] (p. 352).

Sensory perception, Merleau-Ponty argues, is not pure perception of isolated elements [1] (p. 81). When we look around us, things exist in relation to each other. Light and shade blur the boundaries between space and between objects. Things distant from our eyes appear as blurred, meaningless spots. This very vagueness cannot be described or represented by geometric perspective. Any change in the direction of attention alters the visual field. Language creates an artificial separation: “I see something red” or “I feel cold”. Unlike the linguistic way of conceptualizing, the bodily experience is perceived by us as a complex, as something that is always part of something else, or against the background of something else. Anything we perceive is perceived by us as part of a dynamic relationship and never absolutely. The context in which we perceive things is termed by Merleau-Ponty “a field” [1] (pp. 3–4, 9):

Each part arouses the expectation of more than it contains, and this elementary perception is therefore already charged with a meaning… The perceptual “something” is always in the middle of something else, it always forms part of a “field”… The pure impression is, therefore, not only undiscoverable, but also imperceptible and so inconceivable as an instant of perception[1] (p. 4).

We always perceive something in a certain context, something against the background of something else: the moon in the night sky, the tree in the forest, and the building in the street. Things are always perceived as part of a “field”, the visual field. The visual field is both spatial and temporal. Merleau-Ponty refers to the act of perceiving as an action that always has a horizon. Anything perceived awakens in us the expectation of other parts of the same thing (for example, its other aspects) or other things in the same field. In this sense, argues Merleau-Ponty, even this basic act of perception is already “loaded with meaning” [1] (p. 4). Without the context of the visual field, there is no meaning to what we see [1] (pp. 9–10).

Being embodied, we populate the world in a certain way and perceive ourselves in space in a certain way in relation to it and to things within it: left and right, up and down, forward and backward, near and far, and overt and hidden, when our body is at the departure point of the orientation. As a rule, any perception of our being can only occur in the context of direction (orientation) [1] (p. 295):

What counts for the orientation of the spectacle is not my body as it in fact is, as a thing in objective space, but as a system of possible actions, a virtual body with its phenomenal “place” defined by its task and situation[1] (p. 291).

Just as we perceive objects against some background and in a particular context, we also locate ourselves in space. Our own bodies can never become objects of perception, as they are the transcendental condition for the existence of objects. Though we sense our surroundings with our bodies, we are, in a sense, almost virtual. Although our bodies are always present, they are not among the objects surrounding us and cannot be subjected to absolute knowledge [1] (p. 105)13. At any given moment, we are aware through our senses of being bodies present in a particular position or in motion. Merleau-Ponty calls the sensory encounter with the world “motor intentionality” [1] (p. 127)14. This intentionality is necessarily influenced by the environment in which we exist—whether along a river, in a dark alleyway, or up a hill. Merleau-Ponty’s conceptualization of perception as a field connects the subject to the world of objects through the spatial element: the three-dimensional existence of our bodies in space, to which he devotes a separate discussion.

If our consciousness is embodied consciousness, necessarily existing in some concrete space, then consciousness and space are inseparably connected with a deep relationship of existential meaning. Perception is precisely the mode of the body’s belonging to the spatial world. The primordial connection between humans and the world is termed “chiasm” by Merleau-Ponty in his later writings, meaning “in-between” [29] (p. 68); [30]. According to Merleau-Ponty, and similar to the views of phenomenologists like Husserl and Heidegger before him, the world and subjects are inseparable [1] (p. 491); [28] (pp. 393–414). But how do we perceive space?

3.3. Space and Depth

Merleau-Ponty views space as an entity of a different order: it is not an object, nor is it the product of conscious constitution. As if by magic, space appears to us as part of the phenomenal field without appearing itself [1] (p. 296). Observers do not merge with what appears before them and do not become part of it. But observers, in their physical presence, are still part of what appears to them, and through the body and its senses they conduct a sort of relation, a sort of communication, with what appears before them [31] (p. 240); [30] (p. 138).

Merleau-Ponty emphasizes that the space we perceive is an existential rather than a geometric space. Our natural behavior in space occurs without calculating distances and conceptualizing in three-dimensional terms. We cannot experience geometric space because we are physical creatures, always existing in some space from which the perception of the space around us and the objects within it is obtained. The space we perceive is only the one we are within. Our place of existence determines immediately what is considered in space as near or far, up or down, backward or forward [32] (p. 47).

The objective, abstract geometric space is an abstraction of existential space, the space we experience as a physical body. This abstraction is the outcome of men’s occupation of nature through science, a product of theoretical reflection. For Merleau-Ponty, the daily experience of existential space, of a place, is deeply connected first and foremost with the actions in which we are involved, and especially the moving body, that mediates between us and our experience of space. Think about the road we walk along, the bridge we cross. The things we meet are necessarily located in a certain way: the glass on the table, the trees in the avenue, and so on. Experience of different places and spaces is an inseparable part of our encounter with the world around us. So, we cannot reduce the person into a thinking entity, free of a physical body. Merleau-Ponty opens to us the understanding that the space in which we live cannot be the space of Euclidean geometry. Geometric space, the space of digital design software, assumes a detachment from the world. As a theoretical space, it has no point of view from within (unlike the human experience), and its dimensions have equal importance. In effect, geometrical space is a mode of body, a neutral ‘container’ of objects.

The simplest example to demonstrate the deep chasm between geometric space and existential space is, of course, two parallel lines. If we look at two lines drawn on either side of a road, for instance, then in geometric space they are parallel lines, but in space as we perceive it, they appear to meet at the horizon of our vision. We live in a perspectival world, not a geometric one. Buildings closer to us always look larger than buildings at a distance. In the existential space, we know how to read the “small” buildings as located farther away [1] (p. 302). But, as noted above, this does not mean that a perspective simulation on a two-dimensional plane can capture this experience of depth associated with our physical presence within a space.

In geometrical space, a thrown stone passes a trajectory that is a collection of points. In the space we experience, there is a stone before it was thrown, the stone in flight, and the stone in its new location at the end of the fall. The stone’s situations are not neutral and are not identical, like a possible mathematical representation of them as a collection of points [1] (pp. 314, 318). Our existential space is necessarily a hierarchical rather than neutral space in terms of our perception of it. We distinguish between near and far, left and right, center and periphery, my space and my neighbor’s space, and so on. Our field of perception is dynamic. It is always created at a particular moment and in a particular space, from a particular viewpoint, but its boundaries are always blurred rather than absolute, and it changes if we move our body and change our viewpoint. We perceive the world as a sequence of appearances in time and space, and it is vague.

The geometric conception of three-dimensional space treats the three dimensions in the same way, as dimensions of measured length (the X, Y, and Z axes system). But, as Merleau-Ponty says, our existential experience of space grants the depth dimension a special status in the way we construct our vision of the world, since it is an experienced rather than thought dimension [1] (p. 298). The depth dimension is the one that, more than any other, links our bodies to things in the world and to the space itself, because perspective depends on our location in relation to everything appearing before us [1] (p. 311). If so, depth has a primary, original importance in human experience. This perception is essentially different to that of Descartes, who sees depth as a dimension of equal status to the other two dimensions (length and width). In his essay, “Eye and Mind”, Merleau-Ponty discusses the Cartesian concept of depth, saying that “Once depth is understood in this way, we can no longer call it a third dimension. In the first place, if it were a dimension, it would be the first one” [28] (p. 369).

The depth dimension is also related to our being upright walking creatures whose eyes are at the top of our bodies. Like Vitruvius, and the Greeks before him, Merleau-Ponty also refers to the importance of our being bipedal, saying that “We can be tempted to say that the vertical dimension is the direction represented by the symmetry axis of our body as a synergic system” [1] (p. 291). The human phenomenal field is very different to the phenomenal field of quadruped animals or those that crawl on their belly.

The depth dimension is the dimension of inter-subjective encounter, not only the encounter with various objects. In the depth dimension, the world is perceived in the field of vision as a whole, composed of both physical objects and cultural subjects. He presents Paris, his beloved city of residence. For him, Paris is not a multifaceted object, a collection of aspects or gazes, and it is not the constituting rule of all those acts of perception. Everything that makes Paris into Paris, the cafes, people’s faces, and the Seine River, are all perceived within the comprehensive context of the whole that is called Paris, which is already familiar. The spatial perception, achieved through the senses, involves not only all the senses but also any previous knowledge and memory we have in our consciousness about the place where we are [1] (pp. 327–328). The physical, material Paris is inseparable from Paris as an appearance of French society and culture. Thus, Merleau-Ponty opposes the empiricist position that in its reference to nature hides the existence of a world of culture, a world of people. He links the three-dimensional space and human physicality to the meaning of culture and society, saying “They hide from us in the first place “the cultural world” or “human world” in which nevertheless almost our whole life is led [1] (p. 27)”.

The act of sensory perception does not grant us truths, the way geometry does, but rather presences [24] (p. 13). Merleau-Ponty uses the term presence to overcome the traditional division into object and subject, citing Husserl in saying that perception grants the subject “a field of presence” [1] (p. 309). He argues that we cannot attribute solely to motor intentionality the perception of space. Instead, it is enabled due to both the sensing body and the presence of the objects existing together with the perceiving subject in space.

4. Contemporary Digital Representations of Three-Dimensional Architectural Space

4.1. Two-Dimensional Spatial Simulation

The historian of architecture, Dalibor Vesely, viewed the invention of perspective as the start of a process at whose peak we adopt representations as a fantastical reality and thus surrender the dialogue with the challenges that reality itself poses us [33] (p. 61)15. In this respect, where are we at today?

There is no dispute that we are currently in an era of unprecedented technological and digital developments that influence our entire way of life, as well as the modes of operation of various occupations, such as medicine, commerce, finance, communication, education, and of course architecture and urban planning and design. Digital tools in architecture that simulate three-dimensional space on a two-dimensional screen include various CAD software such as Revit 2024 and BIM 360 (building information modeling) and parametric software such as Grasshopper 2. BIM software allows for the integration of the design with all practitioners involved in the project, from the architect via the different consultants all the way to the building site and afterwards for maintenance. BIM software is getting more and more advanced and is now beginning to interact with artificial intelligence tools16. Still, the overlooked “cost” for this undeniably effective, accurate, and comprehensive system is of course lived-space. The three-dimensional digital model is perceived by its creators and handlers as a coordinated complex object that is detached from its surroundings, rather than a space or a place inhabited by embodied people.

Parametric architecture creates three-dimensional forms according to varying calculable complex chosen parameters such as size, shape, and dispersion. This software has brought about an architecture which is characterized by formal complexity and curvilinear features, which were unachievable even twenty years ago17. This technology has enhanced the formalistic approach to design (rather than being oriented to spatial experience), as is manifested in many celebrated projects of architects such as Zaha Hadid, Norman Foster, and Bjarke Ingles. All parameters that can be inserted into this software are quantitative parameters, whereas qualitative parameters such as the quality of lived-space or the dubitable quality of a meaningful place are of course inadmissible.

With the help of rendering software such as Lumion 2023 and many others, two-dimensional images of three-dimensional architecture are becoming ever more realistic and enticing. Paradoxically, the more an architectural simulated image is perceived as realistic, the more we are enchanted by it and ignore the fact that this is in fact a two-dimensional representation of a three-dimensional designed space, much like the people of the Renaissance. Although a rendered image is considered far more a reliable simulation than perspective drawings of the past, we are still situated outside the simulated image. We ourselves as embodied spectators do not experience being in that designed simulated space.

4.2. Three-Dimensional Spatial Simulation

Current cutting-edge technologies of immersive virtual reality (such as Autodesk-live and Enscape) aim to remove this representational gap between the image on a screen and the embodied spectator [39] (p. 32). By returning to the work of James Gibson, whose ecological approach to visual perception influenced the development of virtual reality technology, Baggs et al. stress the cardinal difference between the perception of a static image and ambulatory perception [39] (p. 25)18. According to Gomes et al., virtual reality software is unparalleled with regard to the possibility of visualizing and interacting with an architectural simulated space. Although these tools are not yet in extensive use by architects, and are currently used chiefly for the purpose of presentation of a finished design, it will be used for the creation of the design in the near future [9] (pp. 146, 151).

And still, as Fakahani et al. explain, there are major challenges in the current state of the developed software, including technological limitations, such as monitor precision, tracking and sensing technology, and integrated 3D models and cybersickness, and conclude that “Virtual reality is still unable to create a real life experience in many ways” [8] (p. 2761). The lived-experience of spatiality is missing in virtual reality because the simulated visual space is not anchored in the perceiving body; it is not intertwined with it. Baggs et al. refer to this condition as “ambiguous embodiment”, where there is a “mismatch what they see and what they feel in their body” [39] (p. 33).

Here lies a poignant issue: as long as we are aware that we are entering into a virtual simulation (like putting on the necessary equipment) it will be understood as virtual, spatial to a certain degree, but virtual. And, therefore, as Daniel O’Shiel put it, “no matter how elaborate VR technologies are or become, they remain of the imaginary, digital and irreal order and structure, and are thus virtual in the broad sense, so long as they do not cover all of perception (currently and impossible task) [39] (p. 182)”. The danger lies in opting for a virtual reality that is identical to reality which might lead to the “inversion or even collapse” of the physical reality we so endeavored to simulate [41] (p. 179).

The perception of architectural space is, as Merleau-Ponty suggested, a perception realized immediately by all our senses, and not only by vision. Architectural space is still understood first and foremost as a geometric esthetic composition because, as Juhani Pallasmaa said, “The only sense that is fast enough to keep pace with the astounding increase of speed in the technological world is sight. But the world of the eye is causing us to live increasingly in a perpetual present, flattened by speed, lack of depth and simultaneity” [4] (p. 16).

Pompidou Center in Paris is an architectural icon celebrated for its striking “high-tech” architecture, characterized by the ‘inverted’ design of its facades. In the following section is a case study of phenomenological observation not of the building but of the adjacent Beaubourg Square, often overlooked in the discussions and debates over Pompidou Center. The following analysis examines the Square as an architectural example of a phenomenal field, a field of perception of both the surrounding lived-space and the embodied self. The space of the square will be considered as a collection of phenomenal fields of meaning: fields of spatial, public, and personal19.

5. Beaubourg Square—A Case Study

Pompidou Center (library, music center, and modern art museum—See Figure 3) was constructed between the years 1971 and 1977 after an international competition which was won by the then young and unknown architects Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers. They have created an iconic urban monument that is impossible to ignore. And indeed, upon its completion, the Pompidou Center was opposed by many Parisians, who saw it as a steel and glass monstrosity20. The building’s construction was innovative for its time, and in contrast to what had been normal up to that point, the facade of the building included a prominent array of pipes painted in bright colors (water, air, and so on), creating an unfamiliar and different look that challenged its surroundings21. But in the context of our discussion, the interesting decision taken by the architects involves the space in front of the building: half of the area intended for the project was designed as a large urban square, and the building itself largely preserved the proportions of the average urban block in the surrounding area, characterized by traditional nineteenth-century construction (See Figure 4). Thus, visual congruence was created between the area of the building’s facade and the area of the square in front of the building and also between the building’s volume and the volume of neighboring residential buildings. But the square in front of the building is not there instrumentally just in order to enable a dramatic perspective of the building. It is a phenomenal field of a meaningful spatial experience in its own right, as the following phenomenological description will show.

Figure 3.

The facade of the Pompidou Center from the Beaubourg Square (credit: iStock/Siraanamwong).

Figure 4.

Aerial view of Beaubourg Square and its immediate surroundings (credit: Google Earth).

The square and the building, being connected to a network of streets and squares, are revealed to our eyes while walking (or driving) along the street, in motion (see Figure 4). But since we are not the only people walking down the road—we are in the center of busy Paris—we see not only the buildings and trees in the city but also the people around us, most of whom are also in motion. We perceive them moving both in relation to us and in relation to the static environment. However, in this square, there is a particular presence of the movement and location of the people. The square is lowered on one side from the streets that surround it, so that those who arrive from the higher side to the square become observers at that moment, just as happens in a theatre. The elevated angle of vision and the detachment from the square makes the pedestrians on this side into observers of events that could equally occur at any other location in the city, for example: two people standing and talking, a group of children sitting on the ground and eating their sandwiches, or a woman pushing a baby carriage. Despite this, the spatial and concrete disposition of the square makes all these routine, trivial actions into present urban occurrences in the space of the square. In this architectural setting, the iconic building and the buildings surrounding the square serve as the background for an array of multi-sensory experiences (different voices and noises, people in different kinds of activities and motion, smells, etc.), that when in the right disposition lose their given obviousness and become meaningfully present.

We could say that the whole site is a theatre of viewpoints and gaze horizons: the view from the nearby streets toward the square and the building; the gaze of those within the square towards the facade of the building and the people going up the escalators moving within a transparent pipe on the facade; the gaze of those within the building directed outwards through the transparent facades; and there is another gaze: that of the people inside the transparent pipe with the escalator, who are not engaged in climbing, and their gaze is free to look at the building’s floors on the one side and to the opening vista of the city on the other hand, with a view of the Sacre Coeur, and up to the horizon. These gazes are embodied gazes situated within what Merleau-Ponty called the chiasm, within the space of the square that is experienced as present, as the space where this ‘theatre’ actors can ‘perform’ [45].

The square is simultaneously an integral part of the urban texture and a special architectural space that is experienced as an outdoor interior space. It is a kind of room in the center of Paris. As other successful city squares, such as Piazza Navona in Rome, this square is not perceived as solely the background to human activity but as a spatial entity that has a presence that attracts our attention. Unlike Merleau-Ponty’s claim that when observing an avenue he cannot bring himself to perceive the trees as background and the space between the trees as an object, as the thing he is observing [1] (p. 307), squares such as the square in front of the Pompidou Center is an observable experiential space.

The depth dimension is particularly present in the square: the Square is slightly lowered in relation to some of the surrounding streets, and it sinks with a slight decline toward the facade of the Pompidou Center. The open square allows for a wider angle and opens to us a large, rich phenomenal field. The transparent building facades allow those in the square to see through the building’s facades to the road on its other side. People in the square feel as though they are in a very large room with many other people, but another powerful feeling is added to the sense of observing and being observed—a sense of presence. Suddenly, our embodied presence and the presence of others are experienced as an existential meaning, as something out of the ordinary. Our presence in our bodies in a space with other objects and subjects stops being obvious and attracts all of our attention. We find ourselves engaged in our very being as a body that exists there with others.

The architectural space created in Beaubourg Square is a dynamic space with multiple existential and ontological meanings. If the people within it are free from thoughts and concerns, they find themselves suddenly present elsewhere. They are not present within it alone, but always in the company of others, whose presence is experienced differently. This type of architectural spatial experience can only be understood with hindsight. It cannot be replicated on demand, and, therefore, it is no accident that good architecture does not exist everywhere. Spaces that attract us to them, spaces that we perceive as delightful and significant, are the outcome of countless factors, many of which cannot be separated and diagnosed in advance. We have to beware of the constant urge to propose “recipes” for good architecture, lest we get caught up in a scientific paradigm, as Merleau-Ponty writes in the article “Eye and Mind”:

Science manipulates things and gives up dwelling in them. It gives itself internal models of the things, and, operating on the basis of these indices or variables, the transformations that are permitted by their definition, science confronts the actual world only from greater and greater distances. It is, and always has been, that admirably active, ingenious, and bold way of thinking, that one-sided thought that treats every being as an object in general, that is, at once as if all being were nothing to us and, however, is discovered predestined for our artifices [28] (p. 351).

6. Conclusions

Beaubourg Square was designed in the 1970’s solely by hand using traditional two-dimensional drawings of three-dimensional architecture. Surely, had current imaging and simulation existed back then (and indeed they do so today), they would have used them, but these tools could never replace their own imagination and intuition as well as their attitude and understanding of urban culture. These qualities are responsible for the creation of an urban square that is not a left-over space or a lost space but a space that allows for an experience of a bond between our embodied selves and the world, a bond of existential meaning, that Merleau-Ponty labored to explicate.

Experiencing embodied presences constitutes a hint to the existence of an original, essential layer of meaning that exists everywhere but is usually concealed by a reality “ruled over” by objects and that is non-existent in virtual simulations and images. Good architecture, therefore, enables us, even for a brief moment, to experience the place where we are at together with our own being as a meaningful unity, as a whole, that is ontologically and existentially present. Our experience of being present is meaningful as an experience, not as knowledge.

Merleau-Ponty’s phenomenological analysis of the perception of body and space reveals the depth and wealth of the human physical, pre-intentional experience of its surroundings, which architects should once more recognize as fundamental to architecture making and strive to reveal and augment in their designs. The subjective experience of our body in space does not subject itself to adequate representation, digital or manual, and exceeds the scientific–geometric conception of three-dimensional objective space. Understanding our intricate modes of perceiving physical space as an existential meaningful space can help elucidate places in the city that are considered good and that people flock to, and places in the city that are perceived as “nowhere”, and also to constantly doubt the “reality” represented to us in architectural simulations.

Three-dimensional spatial perception is always from the particular viewpoint of the situated and often moving human body, which, apart from its ability to perceive its surroundings with its senses, is an embodied presence in space, a very meaningful as well as aesthetic experience of presence that eludes past and present-day means of three-dimensional representation. Our spatial perception is obtained from within a space and never from “the outside” as is the case when looking at an architectural simulation on a computer screen.

If architects can really learn something useful from Phenomenology of Perception, it is to keep in mind that the human body and three-dimensional space are inherently intertwined and that their designs are embedded within a built spatial context and not within the geometrically simulated virtual spaces. Architecture that is made with due consideration of the line between space and our embodiment, and that does not rely with absolute conviction on its digital simulation, has the potential to be not only useful and beautiful, but also existentially meaningful.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization: Y.C.Y.; Methodology: Y.C.Y.; research, development of concept and writing: Y.C.Y. and E.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Data is contained within the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interests.

Notes

| 1 | Steven Holl, Alberto Pérez-Goméz, and Juhani Pallasmaa, Questions of Perception: Phenomenology of Architecture (San Francisco: Wiliiam Stout Publishers, 2006) [3]; Juhani Pallasmaa, The Eyes of the Skin (Chichester: John Wiley and Sons Ltd., 2012) [4]; David Seamon and Robert Mugerauer, eds., Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World (Dordrecht/ Boston/ Lancester: Martinus Nijhoff, 1985) [5]. See also Patricia M. Locke and Rachel Mccann, eds., Merleau Ponty: Space, Place Architecture (Athens: Ohio University Press, 2015) [6]. |

| 2 | Modernistic functionalist approaches to urbanism have brought about the creation of large utilitarian spaces such as vast parking lots, large roads that create inner boundaries (examples of what Jane Jacobs called ‘empty space’, Rem Koolhaas called ‘Junkspace’ [10], and Roger Trancik called ‘lost space’ [11]). Spaces that we inhabit by necessity and their meaning to us are purely functional. |

| 3 | Robin Evans made an interesting observation that the understanding of the one-point perspective, which he attributes to Lucretius already in the first century BCE, was achieved by observing a colonnade. If so, perspective was discovered in the field of architecture, which in turn used perspective, most prominently in Renaissance art and architecture. See [15] (p. 136). |

| 4 | Perspective constituted, among other things, a means for imposing order by the regime, as a tool to shape the space in a way that enabled the control of the citizens. [15] (pp. 141–142). |

| 5 | Panofsky relies on Cassirer’s perception whereby we only know the world through a series of symbols, only one of which is language. |

| 6 | See Rykwert, 1996, on this topic. |

| 7 | Leonardo da Vinci’s famous drawing, “The Vitruvian Man” (1490) is based on Vitruvius descriptions. The proportions that were perceived as harmonious and “correct” in drawing, sculpture, and architecture were those that imitated the proportions found in nature. |

| 8 | In this context, see the famous article of the theoretician Colin Rowe (1920–1999), first published in 1947, in which Rowe demonstrates the similarity between the proportions of two sixteenth-century villas by Palladio and two nineteen-twenties villas by Le Corbusier [21] (pp. 1–28). |

| 9 | Phenomenology deals with the world of phenomena as they appear to the subject, to me, and does not deal with facts. In the phenomenological view, the fact that the world is a planet and has physical qualities is secondary in importance to the way in which we perceive the world as background and as an existential and significant context in which and versus which we weave the fabric of our lives. |

| 10 | By considering the body as the basis for any knowledge of the world, Merleau-Ponty indicates a more basic layer than that of the Husserlian structure of intentionality that connects us with the world, which cannot be fully deciphered. In this context, the absence, which is usually perceived as the opposite of presence, is for Merleau-Ponty a mode of presence of the physical object [24] (pp. 13–14). |

| 11 | He calls this, following the philosopher Martin Heidegger, “embodiment” [25] (p. 182). |

| 12 | Descartes appeals to the cogito since it is the ideal subject of science. Descartes is interested in the cogito because it frees itself from the restrictions of the body and the arbitrariness of the place and time that restrict it, in which the certainty he seeks cannot exist. The commitment to this objectivity, which is a prerequisite for science (the same science that led to the development of digital architectural design tools), distances us from understanding the space as perceived and experienced in the body. Merleau-Ponty’s emphasis on the importance of the body for the act of perception is, in practice, a rejection of the Cartesian body/soul dualism. [1] (p. 71); [27] (p. 682). |

| 13 | The term intentionality is the most basic term in the phenomenological vocabulary. According to Husserl, intentionality means the basic trait of consciousness to transcend itself towards the outer world. |

| 14 | Intentionality, the basic property of consciousness to be directed outside itself, is one of the basic principles of Husserlian phenomenology. Merleau-Ponty is proposing a different conception of intentionality, one that is not anchored solely in consciousness but in the body. |

| 15 | Dalibor Vesely (1934–2015) was a historian of architecture greatly influenced by Edmund Husserl’s phenomenology and by the thought of Heidegger and Gadamer. Another approach is that of Pérez-Goméz and Pelletier, whose article from 1992 (the year commonly viewed as the digital turning point in architecture), “Architectural Representation beyond Perspectivism”, presents the development of the use of linear perspective in architecture as a process of losing the symbolic dimension (symbolic in the profound sense of constructing a cosmic order), the dimension that they believe grants meaning in architecture, so that perspective is now perceived merely as a faithful representation of an empirical reality. Pérez-Goméz and Pelletier predicted that digital technologies would occupy an increasing role in architectural practice and wished to warn against the creation of architectural spaces that contain nothing beyond what appears in those perspective representations during the planning stage [14] (p. 39). |

| 16 | For more information regarding recent developments in BIM see, for example, the following: Cassandro, Jacopo, Mirarchi, Claudio, Gholamzadehmir, Maryam, Pavan, Alberto. (2024). “Advancements and prospects in building information modeling (BIM) for construction: a review.” Engineering, Construction and Architectural Management (2024-07) [34]; Liu, Zhen, He, Yunrui, Demian, Peter and Osmani, Mohamed. “Immersive Technology and Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Sustainable Smart Cities”, Buildings, 2024, 14, 1765 [35]; Liladhar, Nitin, Rane, Choudhary, Saurabh P. and Rane, Jayesh. “Integrating ChatGPT, Bard, and Leading-Edge Generative Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design and Engineering: Applications, Framework, and Challenges”. International Journal of Architecture and Planning, 3(2) 2023, pp. 92–124 [36]. |

| 17 | Regarding current approaches to parametric design see, for example, the following: Yussuf, Naglaa M., Maarouf, Ibrahim and Abdelhamid, Mona M. “Parametric-based Approach in Architectural Design Procedures.” Journal of Fayoum University Faculty of Engineering, Selected papers from the Third International Conference on Advanced Engineering Technologies for Sustainable Development ICAETSD, held on 21 22 November 2023, 7(2), 127–133 [37]; Pektas, Sule Tasli; Guler, Kutay. “Parametric Design as a Tool/ As a Goal: Shifting Focus from Form to Function”, in Guler, Kutay (Ed.), Transforming Issues in Housing Design, 2023, pp. 221–232 [38]. |

| 18 | See Gibson, James J. (1986). The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception, Psychology Press, New-York [40]. |

| 19 | For a similar position that discusses the link between the experience of architectural space and meaning in selected famous projects of architects such as Peter Zumthor and Kengo Kuma, see Soltani, Saeid and Kirci, Nazan (2019). “Phenomenology and Space in Architecture: Experience, Sensation and Meaning”, International Journal of Architectural Engineering Technology, 6, 1–6 [42]. |

| 20 | One of the more famous criticisms is that of Jean Baudriard, who addressed Pompidou Center as an empty simulacrum. See Baudriard, Simulacra, and Simulation, 1994 [43]. |

| 21 | The reason for the relocation of the infrastructure to the external facades of the building, in addition to the desire to amaze, was to create large and flexible internal spaces for the center’s range of activities. For a conversation with Piano and Rogers about the center’s design, see: Piano, Rogers, and Walker, 2015, pp. 46–59 [44]. |

References

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D. Merleau-Ponty, Lived Body, and Place: Toward a Phenomenology of Human Situatedness. In Situatedness and Place; Hunefeldt, T., Schlitte, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 41–66. [Google Scholar]

- Holl, S.; Pérez-Goméz, A.; Pallasmaa, J. Questions of Perception: Phenomenology of Architecture; Wiliiam Stout Publishers: San Francisco, CA, USA, 2006. [Google Scholar]

- Pallasmaa, J. The Eyes of the Skin; John Wiley and Sons Ltd.: Chichester, UK, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- Seamon, D.; Mugerauer, R. (Eds.) Dwelling, Place and Environment: Towards a Phenomenology of Person and World; Martinus Nijhoff: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Boston, MA, USA; Lancester, UK, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Locke, P.M.; McCann, R. (Eds.) Merleau Ponty: Space, Place Architecture; Ohio University Press: Athens, Greece, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Holischka, T. Virtual Places as Real Places: A Distinction of Virtual Places from Possible and Fictional Worlds. In Situatedness and Place; Hunefeldt, T., Schlitte, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 173–185. [Google Scholar]

- Fakahani, L.; Aljehani, S.; Baghdadi, R.; El-Shorbagy, A.M. The Use and Challenges of Virtual Reality in Architecture. Civ. Eng. Archit. 2022, 10, 2754–2763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomes, E.; Rebelo, F.; Boas, N.V.; Noriega, P.; Vilar, E. Architecture, Virtual Reality, and User Experience. In Virtual and Augmented Reality for Architecture and Design; Elisangela, V., Ernesto, F., Francisco, R., Eds.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Koolhaas, R. Junkspace. Ocotober 2002, 100, 175–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trancik, R. Finding Lost Space—Theories of Urban Design; Van Nostrand Reinhold Company: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Zevi, B. Architecture as Space; Gendel, M., Translator; Da Capo Press: New York, NY, USA, 1974. [Google Scholar]

- Alberti, L.B. On Painting; Sinisgalli, R., Translator; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Pérez-Gómez, A.; Pelletier, L. Architectural Representation beyond Perspectivism. Source Perspecta 1992, 27, 20–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evans, R. The Projective Cast: Architecture and Its Three Geometries; The MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, B. Principles of Linear Perspective; M. Taylor: London, UK, 1835. [Google Scholar]

- Panofsky, E. Perspective as Symbolic Form; Christopher, S., Translator; Wood. Zone Books: New York, NY, USA, 1991. [Google Scholar]

- Cassirer, E. The Philosophy of Symbolic Forms; Manheim, R., Translator; Yale University Press: New Haven, CT, USA; London, UK, 1980; Volumes 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson Jones, M. Doric Figuration. In Body and Building; Dodds, G., Tavernor, R., Eds.; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 2002; pp. 64–77. [Google Scholar]

- Vitruvius. The Ten Books on Architecture; Morgan, M.H., Translator; Dover Publications: Mineola, NY, USA, 1960. [Google Scholar]

- Rowe, C. The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa. In The Mathematics of the Ideal Villa and Other Essays; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA; London, UK, 1995; pp. 1–28. [Google Scholar]

- Ruskin, J. The Seven Lamps of Architecture; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Corbusier, L. Towards a New Architecture; Etchells, F., Translator; Dover Publications: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Primacy of Perception; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D. Husserl and Merleau-Ponty on Embodied Experience. In Advancing Phenomenology; Nenon, T., Blosser, P., Eds.; Springer Science+Buisness Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands; Heidelberg, Germany; London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2010; pp. 175–195. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Signs; McCleary, R., Translator; North Western University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Zahavi, D. Phenomenology. In The Routledge Companion to 20th Century Philosophy; Moran, D., Ed.; Routledge: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2008; pp. 661–692. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Eye and Mind. In The Mereau-Ponty Reader; Toadvine, T., Lawlor, L., Eds.; North Western University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 351–378. [Google Scholar]

- Carman, T. Sensation, Judgment and the Phenomenal Field. In The Cambridge Companion to Merleau-Ponty; Carman, T., Hansen, M., Eds.; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2006; pp. 50–73. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Visible and the Invisible; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Moran, D. Between Vision and Touch: From Husserl to Merleau-Ponty. In Carnal Hermeneutics; Kearney, R., Treanor, B., Eds.; Fordham University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 214–234. [Google Scholar]

- Dodd, J. Idealism and Corporeity; Springer Science+Buisness Media: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1997. [Google Scholar]

- Vesely, D. Architecture and the Conflict of Representation. AA Files 1985, 8, 21–38. [Google Scholar]

- Cassandro, J.; Mirarchi, C.; Gholamzadehmir, M.; Pavan, A. Advancements and prospects in building information modeling (BIM) for construction: A review. Eng. Constr. Archit. Manag. 2024; ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; He, Y.; Demian, P.; Osmani, M. Immersive Technology and Building Information Modeling (BIM) for Sustainable Smart Cities. Buildings 2024, 14, 1765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nitin Rane, L.; Choudhary, S.P.; Rane, J. Integrating ChatGPT, Bard, and Leading-Edge Generative Artificial Intelligence in Architectural Design and Engineering: Applications, Framework, and Challenges. Int. J. Archit. Plan. 2023, 3, 92–124. [Google Scholar]

- Yussuf, N.; Maarouf, I.; Abdelhamid, M.M. Parametric-based Approach in Architectural Design Procedures. J. Fayoum Univ. Fac. Eng. 2023, 7, 127–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pektas, S.T.; Kutay, G. Parametric Design as a Tool/As a Goal: Shifting Focus from Form to Function; Guler, K., Ed.; Transforming Issues in Housing Design; John Wiley and Sons Inc.: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2023; pp. 221–232. [Google Scholar]

- Baggs, E.; Grabarczyk, P.; Rucinska, Z. The Visual Information in Virtual Reality. Ecol. Psychol. 2024, 36, 24–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibson, J.J. The Ecological Approach to Visual Perception; Psychology Press: New York, NY, USA, 1986. [Google Scholar]

- O’Sheiel, D. The Phenomenology of Virtual Technology; Bloomsbury Publishing: London, UK; New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Soltani, S.; Kirci, N. Phenomenology and Space in Architecture: Experience, Sensation and Meaning. Int. J. Archit. Eng. Technol. 2019, 6, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baudriard, J. Simulacra and Simulation; University of Michigan Press: Ann Arbor, MI, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Piano, R.; Rogers, R.; Walker, E. Renzo Piano and Richard Rogers in Conversation with Enrique Walker. AA Files 2015, 70, 46–59. [Google Scholar]

- Merleau-Ponty, M. The Intertwining—The Chiasm. In The Mereau-Ponty Reader; Toadvine, T., Lawler, L., Eds.; Northwestern University Press: Evanston, IL, USA, 2007; pp. 393–414. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).