Development of an ELISA Using Recombinant Chimeric SM Protein for Serological Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

Statistical Analysis

3. Results

3.1. Construction, Expression, and Purification of Chimeric Protein

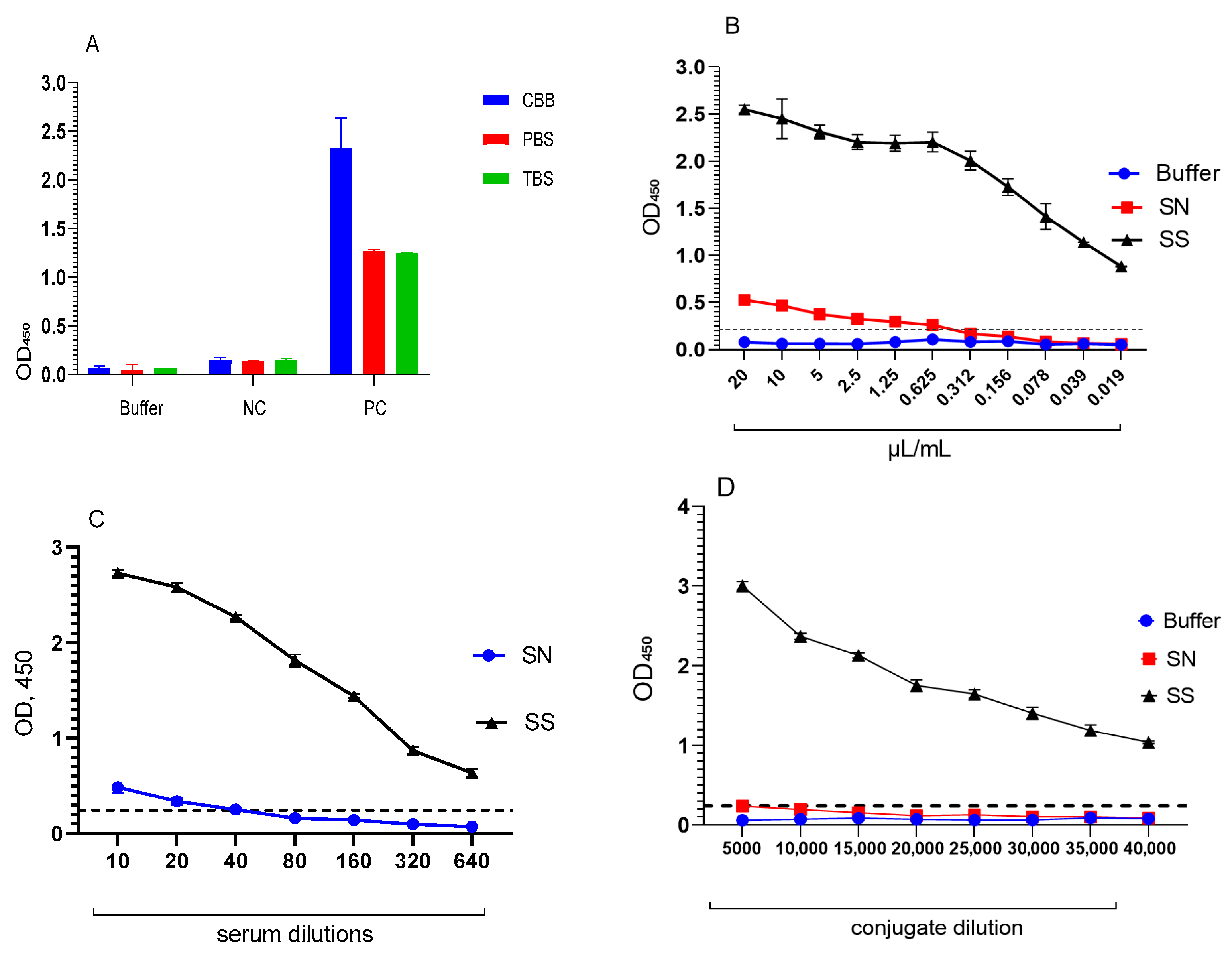

3.2. Optimisation of the ELISA Test System Using a Chimeric Polyepitope Protein

3.2.1. Assessment of the Specificity of the ELISA Test System

3.2.2. Determination of Sensitivity and Specificity of the ELISA Test System

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| SARS-CoV-2 | Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus 2 |

| COVID-19 | Coronavirus Disease 2019 |

| ELISA | Enzyme-Linked immunosorbent assay |

| PCR | Polymerase Chain Reaction |

| BSA | Bovine serum albumin |

| TMB | 3,3’,5,5’-tetramethylbenzidine |

| IPTG | Isopropyl β-D-1-thiogalactopyranoside |

| CBB | Carbonate-bicarbonate buffer |

| PBS | Phosphate-buffered saline |

| TBS | Tris-buffered solution |

| OD | Optical density |

| VNT | Virus neutralisation test |

References

- World Health Organization. Timeline of WHO’s Response to COVID-19. World Health Organization. Available online: https://www.who.int/emergencies/diseases/novel-coronavirus-2019/interactive-timeline (accessed on 15 April 2025).

- Rathmann, W.; Kuss, O.; Kostev, K. Incidence of newly diagnosed diabetes after COVID-19. Diabetologia 2022, 65, 949–954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. Therapeutics and COVID-19: Living Guideline; Version 11.0; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022; Available online: https://iris.who.int/handle/10665/340374 (accessed on 11 April 2025).

- Crist, C. Paxlovid Reduces Risk of COVID Death by 79% in Older Adults: Study. Medscape. Available online: https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/975949 (accessed on 6 June 2022).

- Young, D.R.; Sallis, J.F.; Baecker, A.; Smith, J.K.; McKenzie, T.L.; Cohen, D.A.; Nau, C.L.; Smith, G.N.; Kerr, J. Associations of physical inactivity and COVID-19 outcomes among subgroups. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2023, 64, 492–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mladenovic Stokanic, M.; Simovic, A.; Jovanovic, V.; Radomirovic, M.; Udovicki, B.; Krstic Ristivojevic, M.; Djukic, T.; Vasovic, T.; Acimovic, J.; Sabljic, L.; et al. Sandwich ELISA for the quantification of nucleocapsid protein of SARS-CoV-2 based on polyclonal antibodies from two different species. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, H.; Shi, F.; Yin, H.; Jiao, Y.; Wei, P. Development of a double-antibody sandwich ELISA for detection of SARS-CoV-2 variants based on nucleocapsid protein-specific antibodies. Microbiol. Immunol. 2024, 68, 393–398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hao, Y.-F.; Li, S.-H.; Zhang, G.-Z.; Xu, Y.; Long, G.-Z.; Lu, X.-X.; Cui, S.-J.; Qin, T. Establishment of an indirect ELISA-based method involving the use of a multiepitope recombinant S protein to detect antibodies against canine coronavirus. Arch. Virol. 2021, 166, 1877–1883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramos, F.F.; Pereira, I.A.G.; Cardoso, M.M.; Bandeira, R.S.; Lage, D.P.; Scussel, R.; Anastacio, R.S.; Freire, V.G.; Melo, M.F.N.; Oliveira-da-Silva, J.A.; et al. B-cell epitopes-based chimeric protein from SARS-CoV-2 N and S proteins is recognized by specific antibodies in serum and urine samples from patients. Viruses 2023, 15, 1877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malik, Y.S.; Kumar, P.; Ansari, M.I.; Hemida, M.G.; El Zowalaty, M.E.; Abdel-Moneim, A.S.; Ganesh, B.; Salajegheh, S.; Natesan, S.; Sircar, S.; et al. SARS-CoV-2 spike protein extrapolation for COVID diagnosis and vaccine development. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2021, 8, 607886. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, M.F.; Du, R.L.; Liu, J.Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Q.F.; Han, L.L.; Yu, J.S.; Duan, S.M.; Wang, X.F.; Wu, K.X.; et al. SARS patients-derived human recombinant antibodies to S and M proteins efficiently neutralize SARS-coronavirus infectivity. Biomed. Environ. Sci. 2005, 18, 363–374. [Google Scholar]

- Herrscher, C.; Eymieux, S.; Gaborit, C.; Blasco, H.; Marlet, J.; Stefic, K.; Roingeard, P.; Grammatico-Guillon, L.; Hourioux, C. ELISA-based analysis reveals an anti-SARS-CoV-2 protein immune response profile associated with disease severity. J. Clin. Med. 2022, 11, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, S.; Heslan, C.; Jégou, G.; Eriksson, L.A.; Le Gallo, M.; Thibault, V.; Chevet, E.; Godey, F.; Avril, T. SARS-CoV-2 integral membrane proteins shape the serological responses of patients with COVID-19. PLoS Pathog. 2021, 17, e1009895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jörrißen, P.; Schütz, P.; Weiand, M.; Vollenberg, R.; Schrempf, I.M.; Ochs, K.; Frömmel, C.; Tepasse, P.R.; Schmidt, H.; Zibert, A. Antibody response to SARS-CoV-2 membrane protein in patients of the acute and convalescent phase of COVID-19. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 679841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernandez, Z.; de Arruda Rodrigues, R.; Torres, J.M.; Marcon, G.E.B.; de Castro Ferreira, E.; de Souza, V.F.; Sarti, E.F.B.; Bertolli, G.F.; Araujo, D.; Demarchi, L.H.F.; et al. Development and validity assessment of ELISA test with recombinant chimeric protein of SARS-CoV-2. J. Immunol. Methods 2023, 519, 113489. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Freitas, N.E.M.; Santos, E.F.; Leony, L.M.; Silva, Â.A.O.; Daltro, R.T.; Vasconcelos, L.C.M.; Duarte, G.A.; Oliveira da Mota, C.; Silva, E.D.; Celedon, P.A.F.; et al. Double-antigen sandwich ELISA based on chimeric antigens for detection of antibodies to Trypanosoma cruzi in human sera. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2022, 16, e0010290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, F.L.; Celedon, P.A.; Zanchin, N.I.; Brasil Tde, A.; Foti, L.; Souza, W.V.; Silva, E.D.; Gomes Yde, M.; Krieger, M.A. Performance assessment of four chimeric Trypanosoma cruzi antigens based on antigen-antibody detection for diagnosis of chronic Chagas disease. PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0161100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferra, B.T.; Chyb, M.; Skwarecka, M.; Gatkowska, J. The trivalent recombinant chimeric proteins containing immunodominant fragments of Toxoplasma gondii SAG1 and SAG2 antigens in their core: A good diagnostic tool for detecting IgG antibodies in human serum samples. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasenov, M.M.; Orynbayev, M.B.; Zakarya, K.; Kerimbayev, A.A.; Zhugunissov, K.D.; Sultankulova, K.T.; Myrzakhmetova, B.S.; Nakhanov, A.K.; Kassenov, M.M.; Abduraimov, Y.O.; et al. Strain “SARS-CoV-2/KZ_Almaty/04.2020” of Coronavirus Infection COVID-19 Used for Preparation of Means of Specific Prophylaxis, Laboratory Diagnostics, and Evaluation of Vaccine Biological Protection Effectiveness. Patent 34762, 2020. Republic of Kazakhstan. [Google Scholar]

- NCBI GenBank. SARS-CoV-2 Isolate hCoV-19/Kazakhstan/MZ379258.1, Complete Genome (Accession No. MZ379258.1). National Center for Biotechnology Information. 2021. Available online: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/nuccore/MZ379258.1 (accessed on 24 January 2025).

- Hoover, D.M.; Lubkowski, J. DNAWorks: An automated method for designing oligonucleotides for PCR-based gene synthesis. Nucleic Acids Res. 2002, 30, e43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lowry, O.H.; Rosebraugh, N.J.; Farr, A.L.; Randall, R.J. Protein measurement with the Folin phenol reagent. J. Biol. Chem. 1951, 193, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Laemmli, U.K. Cleavage of structural proteins during the assembly of the head of bacteriophage T4. Nature 1970, 227, 680–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Evseenko, V.A.; Zaikovskaya, A.V.; Gudyumo, A.S.; Taranov, O.S.; Olkin, S.E.; Sultankulova, K.T.; Prudnikova, E.Y.; Danilchenko, N.V.; Shulgina, I.S.; Zakarya, K.; et al. Assessment of the humoral immune response of experimental animals to the administration of recombinant ectodomain of SARS-CoV-2 S-glycoprotein with ISCOM-adjuvant. Bioprep. Profil. Diagn. Lechenie 2023, 23, 530–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molecular Devices. Better Metrics for Comparing Instruments and Assays [Application Note]. Available online: https://www.moleculardevices.com/en/assets/app-note/br/better-metrics-for-comparing-instruments-and-assays (accessed on 5 September 2025).

- Reed, L.J.; Muench, H. A simple method of estimating fifty percent endpoints. Am. J. Epidemiol. 1938, 27, 493–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.-H.; Chung, T.D.Y.; Oldenburg, K.R. A simple statistical parameter for use in evaluation and validation of high throughput screening assays. J. Biomol. Screen. 1999, 4, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Ma, M.L.; Lei, Q.; Wang, F.; Hong, W.; Lai, D.Y.; Hou, H.; Xu, Z.W.; Zhang, B.; Chen, H.; et al. Linear epitope landscape of the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein constructed from 1051 COVID-19 patients. Cell Rep. 2021, 34, 108915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, Z.; Ling, Y.; Zhang, X.; Chen, J.; Hu, K.; Wang, Y.; Song, W.; Ying, T.; Zhang, R.; Lu, H.; et al. Functional mapping of B-cell linear epitopes of SARS-CoV-2 in COVID-19 convalescent population. Emerg. Microbes Infect. 2020, 9, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrock, E.; Fujimura, E.; Kula, T.; Timms, R.T.; Lee, I.H.; Leng, Y.; Robinson, M.L.; Sie, B.M.; Li, M.Z.; Chen, Y.; et al. Viral epitope profiling of COVID-19 patients reveals cross-reactivity and correlates of severity. Science 2020, 370, eabd4250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mamaghani, A.J.; Arab-Mazar, Z.; Heidarzadeh, S.; Ranjbar, M.M.; Molazadeh, S.; Rashidi, S.; Niazpour, F.; Naghi Vishteh, M.; Bashiri, H.; Bozorgomid, A.; et al. In-silico design of a multi-epitope for developing sero-diagnosis detection of SARS-CoV-2 using spike glycoprotein and nucleocapsid antigens. Netw. Model. Anal. Health Inform. Bioinform. 2021, 10, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Phan, I.Q.; Subramanian, S.; Kim, D.; Murphy, M.; Pettie, D.; Carter, L.; Anishchenko, I.; Barrett, L.K.; Craig, J.; Tillery, L.; et al. In silico detection of SARS-CoV-2 specific B-cell epitopes and validation in ELISA for serological diagnosis of COVID-19. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 4290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Poh, C.M.; Carissimo, G.; Wang, B.; Amrun, S.N.; Lee, C.Y.; Chee, R.S.; Fong, S.W.; Yeo, N.K.; Lee, W.H.; Torres-Ruesta, A.; et al. Two linear epitopes on the SARS-CoV-2 spike protein that elicit neutralising antibodies in COVID-19 patients. Nat. Commun. 2020, 11, 2806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrera-Soler, L.; Daguer, J.P.; Barluenga, S.; Vadas, O.; Cohen, P.; Pagano, S.; Yerly, S.; Kaiser, L.; Vuilleumier, N.; Winssinger, N. Identification of immunodominant linear epitopes from SARS-CoV-2 patient plasma. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0238089. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Franken, K.L.; Heemstra, H.S.; van Meijgaarden, K.E.; Subronto, Y.; den Hartigh, J.; Ottenhoff, T.H.; Drijfhout, J.W. Purification of his-tagged proteins by immobilized chelate affinity chromatography: The benefits from the use of organic solvent. Protein Expr. Purif. 2000, 18, 95–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, J.; Brakel, A.; Krizsan, A.; Bente, D.A.; Meyer, B. Sensitive and specific serological ELISA for the detection of SARS-CoV-2 infections. Virol. J. 2022, 19, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimech, W.; Curley, S.; Cai, J.J. Comprehensive, comparative evaluation of 25 automated SARS-CoV-2 serology assays. Microbiol. Spectr. 2024, 12, e03228-23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Souris, M.; Tshilolo, L.; Parzy, D.; Lobaloba Ingoba, L.; Ntoumi, F.; Kamgaing, R.; Ndour, M.; Mbongi, D.; Phoba, B.; Tshilolo, M.A.; et al. Pre-pandemic cross-reactive immunity against SARS-CoV-2 among Central and West African populations. Viruses 2022, 14, 2259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kharlamova, N.; Dunn, N.; Bedri, S.K.; Jerling, S.; Almgren, M.; Faustini, F.; Gunnarsson, I.; Rönnelid, J.; Pullerits, R.; Gjertsson, I.; et al. False positive results in SARS-CoV-2 serological tests for samples from patients with chronic inflammatory diseases. Front. Immunol. 2021, 12, 666114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| № | Sample Category | Etiological Agent/Subgroup | Number of Samples | Storage Temperature |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Seasonal sera, pre-pandemic | HcoV | 6 | −80 °C |

| 2 | Cross-reactive (respiratory viruses) | Influenza | 11 | −80 °C |

| Parainfluenza | 9 | −80 °C | ||

| Adenovirus | 9 | −80 °C | ||

| 3 | Cross-reactive (other) | Herpesviruses | 15 | −80 °C |

| Sera/Infection | Number of Samples, n | False-Positive Samples (FP) | Specificity, % (95% CI) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Influenza | 11 | 1 | 90.9 (58.7–99.8) |

| Seasonal HCoV, pre-pandemic | 5 | 0 | 100 (47.8–100) |

| Parainfluenza | 6 | 0 | 100 (54.1–100) |

| Adenovirus | 9 | 1 | 88.9 (51.8–99.7) |

| Herpesviruses | 15 | 1 | 93.3 (68.0–99.8) |

| Total | 46 | 3 | 93.5 (82.1–98.6) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Nakhanova, G.; Chervyakova, O.; Shorayeva, K.; Issabek, A.; Moldagulova, S.; Zhunushov, A.; Ulankyzy, A.; Zhakypbek, A.; Omurtay, A.; Nakhanov, A.; et al. Development of an ELISA Using Recombinant Chimeric SM Protein for Serological Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Methods Protoc. 2026, 9, 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010004

Nakhanova G, Chervyakova O, Shorayeva K, Issabek A, Moldagulova S, Zhunushov A, Ulankyzy A, Zhakypbek A, Omurtay A, Nakhanov A, et al. Development of an ELISA Using Recombinant Chimeric SM Protein for Serological Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Methods and Protocols. 2026; 9(1):4. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010004

Chicago/Turabian StyleNakhanova, Gulnur, Olga Chervyakova, Kamshat Shorayeva, Aisha Issabek, Sabina Moldagulova, Asankadyr Zhunushov, Aknur Ulankyzy, Aigerim Zhakypbek, Alisher Omurtay, Aziz Nakhanov, and et al. 2026. "Development of an ELISA Using Recombinant Chimeric SM Protein for Serological Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies" Methods and Protocols 9, no. 1: 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010004

APA StyleNakhanova, G., Chervyakova, O., Shorayeva, K., Issabek, A., Moldagulova, S., Zhunushov, A., Ulankyzy, A., Zhakypbek, A., Omurtay, A., Nakhanov, A., Absatova, Z., Shayakhmetov, Y., Jekebekov, K., Baiseit, T., & Kerimbayev, A. (2026). Development of an ELISA Using Recombinant Chimeric SM Protein for Serological Detection of SARS-CoV-2 Antibodies. Methods and Protocols, 9(1), 4. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps9010004