Fluorescence-Based Detection of KRAS Mutations in Genomic DNA Using Magnetic Bead-Coupled LDR Assay

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

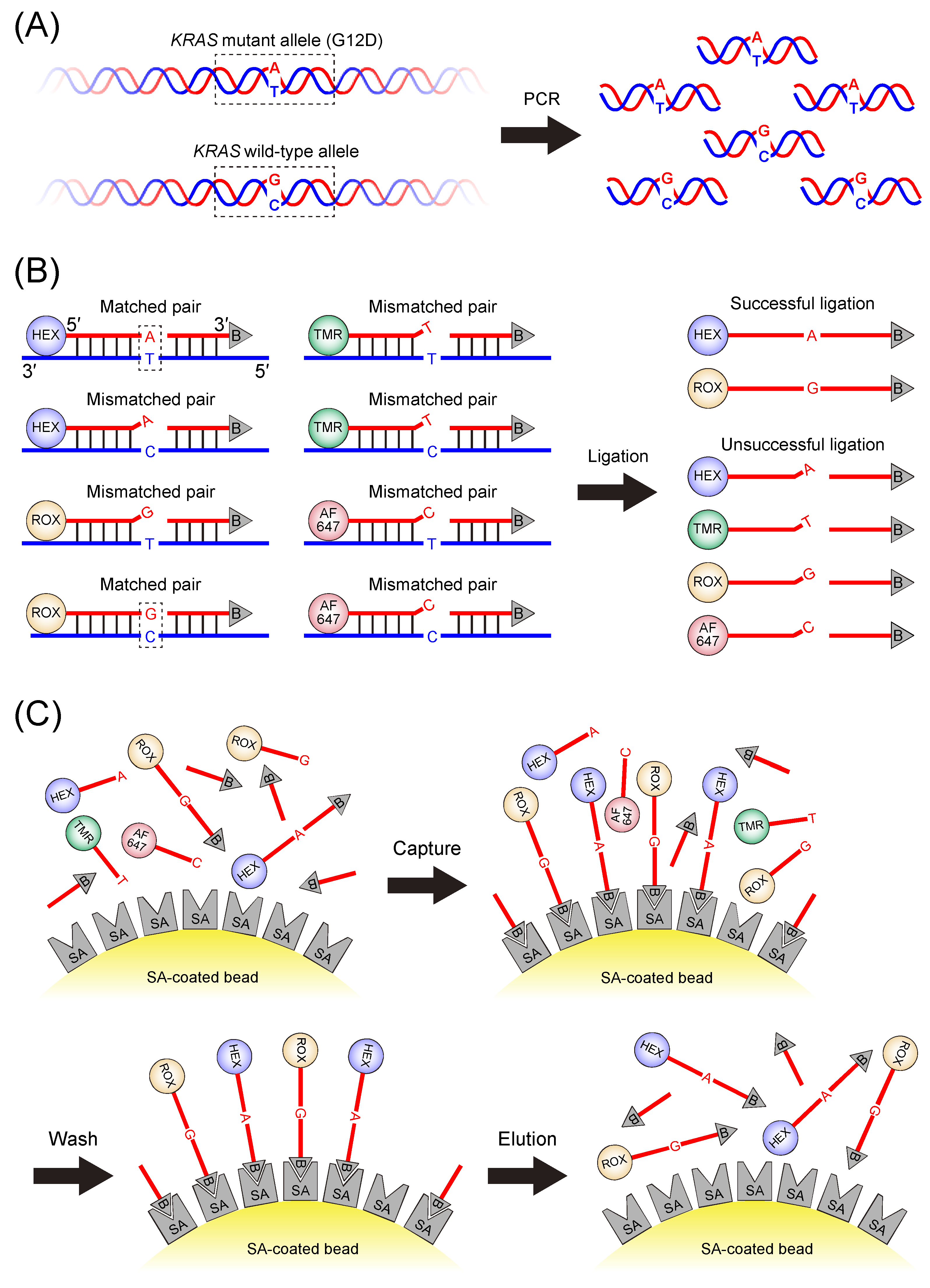

2.2. Preparation of Template DNA and PCR

2.3. LDR

2.4. Purification of LDR Products

2.5. Fluorescence Measurements

3. Results and Discussion

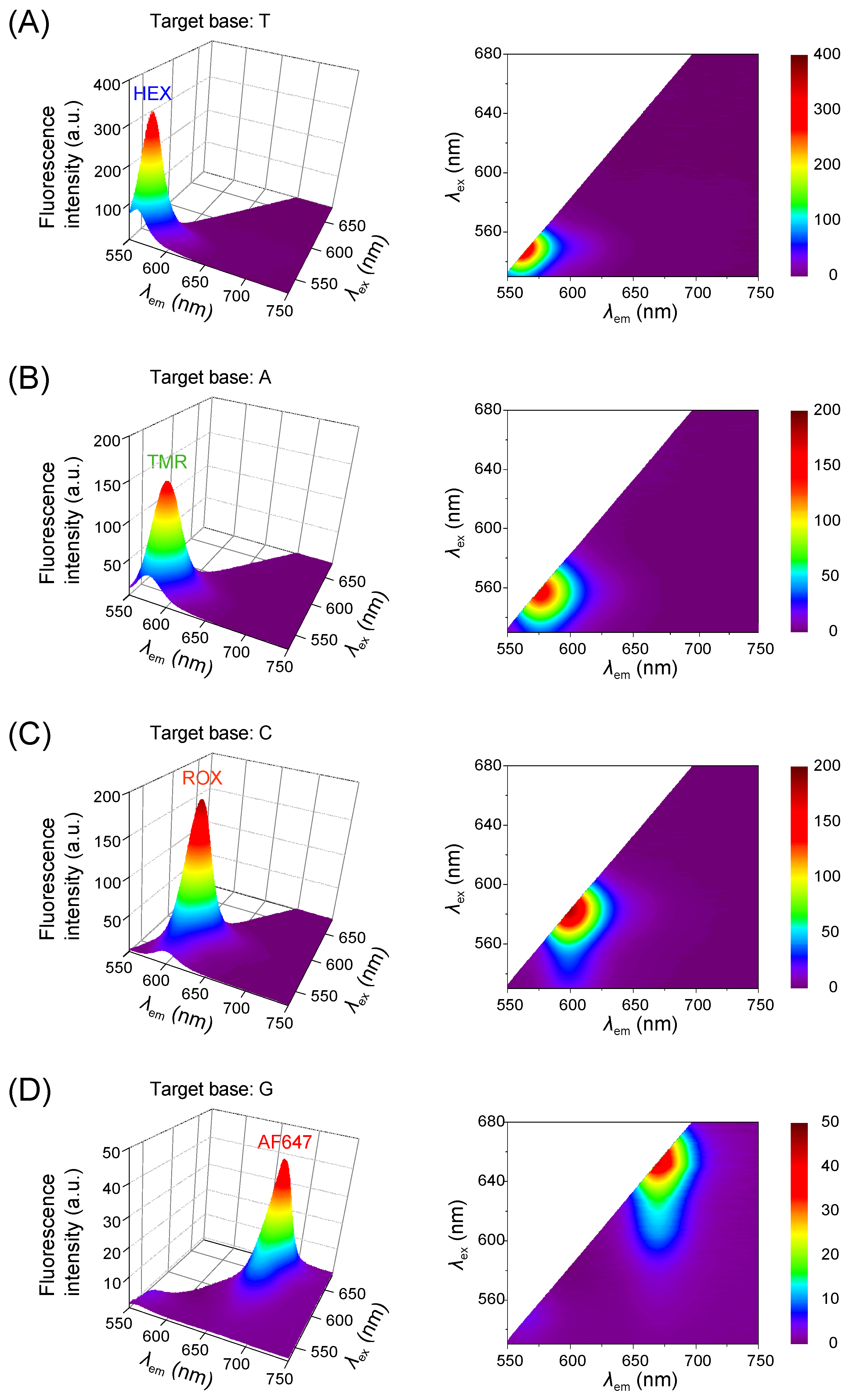

3.1. Validation with Synthetic Templates

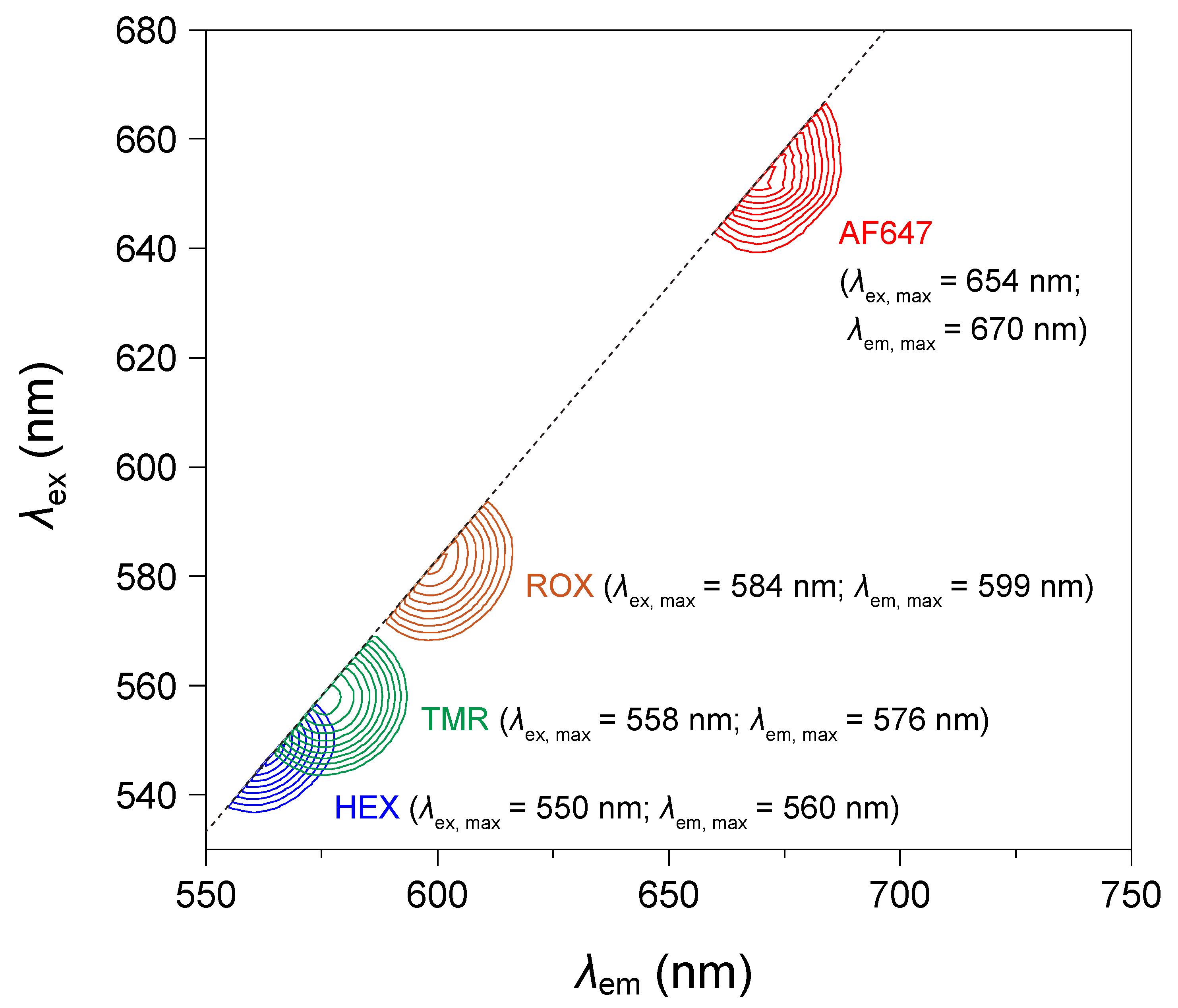

3.2. Spectral Distinctiveness of Fluorophores

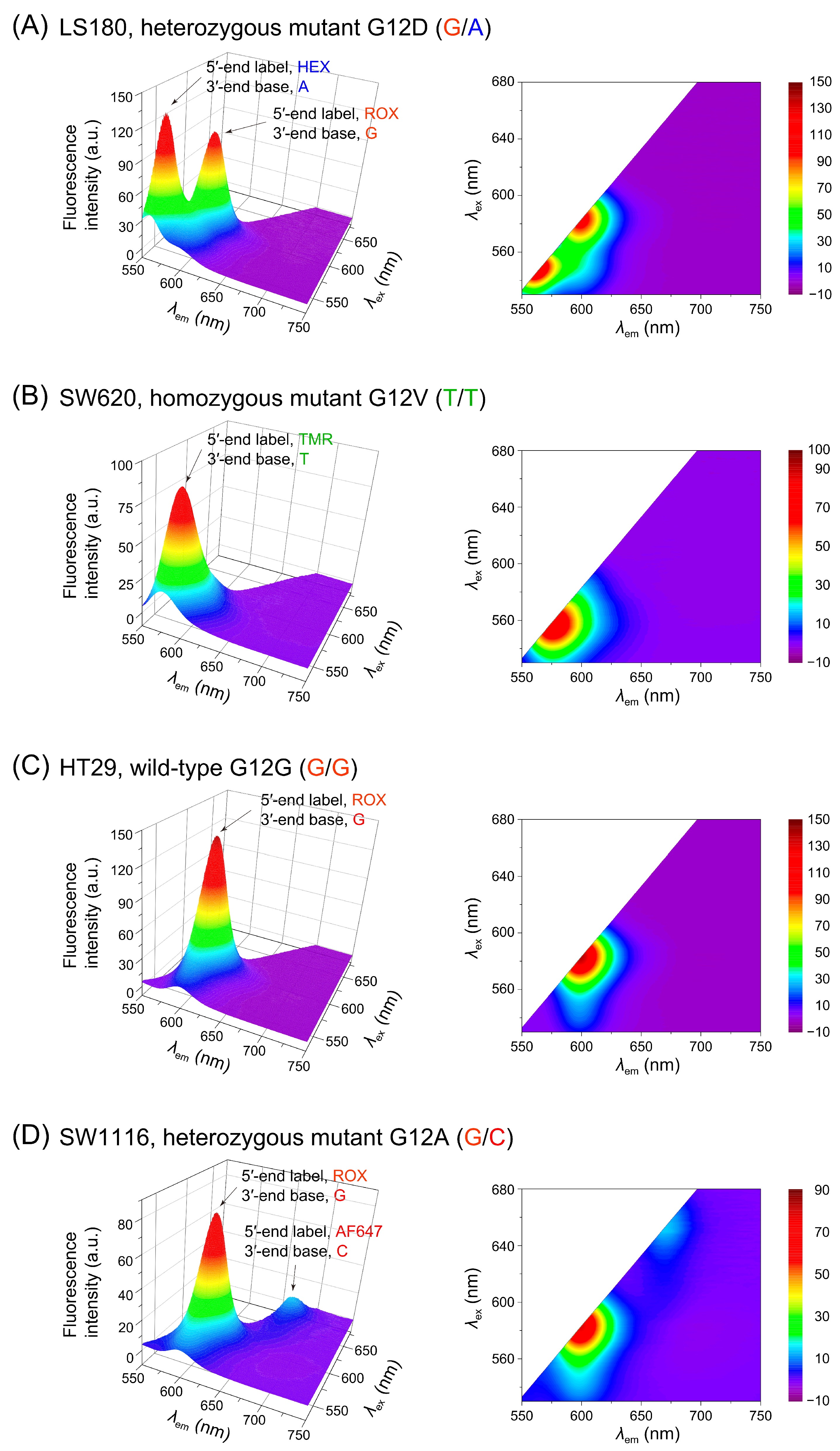

3.3. Application to Genomic DNA and Signal Considerations

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Auton, A.; Abecasis, G.R.; Altshuler, D.M.; Durbin, R.M.; Abecasis, G.R.; Bentley, D.R.; Chakravarti, A.; Clark, A.G.; Donnelly, P.; Eichler, E.E.; et al. A global reference for human genetic variation. Nature 2015, 526, 68–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frazer, K.A.; Murray, S.S.; Schork, N.J.; Topol, E.J. Human genetic variation and its contribution to complex traits. Nat. Rev. Genet. 2009, 10, 241–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alexandrov, L.B.; Nik-Zainal, S.; Wedge, D.C.; Aparicio, S.A.J.R.; Behjati, S.; Biankin, A.V.; Bignell, G.R.; Bolli, N.; Borg, A.; Børresen-Dale, A.-L.; et al. Signatures of mutational processes in human cancer. Nature 2013, 500, 415–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vogelstein, B.; Papadopoulos, N.; Velculescu, V.E.; Zhou, S.; Diaz, L.A.; Kinzler, K.W. Cancer Genome Landscapes. Science 2013, 339, 1546–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garraway, L.A.; Verweij, J.; Ballman, K.V. Precision Oncology: An Overview. J. Clin. Oncol. 2013, 31, 1803–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marinković, M.; de Leeuw, W.C.; de Jong, M.; Kraak, M.H.S.; Admiraal, W.; Breit, T.M.; Jonker, M.J. Combining Next-Generation Sequencing and Microarray Technology into a Transcriptomics Approach for the Non-Model Organism Chironomus riparius. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e48096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nakamura, T.; Furukawa, Y.; Nakagawa, H.; Tsunoda, T.; Ohigashi, H.; Murata, K.; Ishikawa, O.; Ohgaki, K.; Kashimura, N.; Miyamoto, M.; et al. Genome-wide cDNA microarray analysis of gene expression profiles in pancreatic cancers using populations of tumor cells and normal ductal epithelial cells selected for purity by laser microdissection. Oncogene 2004, 23, 2385–2400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Batan Pumeda, S. Comparison Between Next-Generation Sequencing and Microarrays for miRNA Expression in Cancer Samples. Natl. Acad. Sci. Lett. 2024, 47, 587–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barany, F. Genetic disease detection and DNA amplification using cloned thermostable ligase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 189–193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Cao, W.; Zirvi, M.; Paty, P.; Barany, F. Ligase detection reaction for identification of low abundance mutations. Clin. Biochem. 1999, 32, 287–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khanna, M.; Park, P.; Zirvi, M.; Cao, W.; Picon, A.; Day, J.; Paty, P.; Barany, F. Multiplex PCR/LDR for detection of K-ras mutations in primary colon tumors. Oncogene 1999, 18, 27–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafer, R.W.; Winters, M.A.; Mayers, D.L.; Japour, A.J.; Kuritzkes, D.R.; Weislow, O.S.; White, F.; Erice, A.; Sannerud, K.J.; Iversen, A.; et al. Interlaboratory comparison of sequence-specific PCR and ligase detection reaction to detect a human immunodeficiency virus type 1 drug resistance mutation. The AIDS Clinical Trials Group Virology Committee Drug Resistance Working Group. J. Clin. Microbiol. 1996, 34, 1849–1853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niederhauser, C.; Kaempf, L.; Heinzer, I. Use of the Ligase Detection Reaction-Polymerase Chain Reaction to Identify Point Mutations in Extended-Spectrum Beta-Lactamases. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2000, 19, 477–480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Belgrader, P.; Marino, M.M.; Lubin, M.; Barany, F. A Multiplex PCR-Ligase Detection Reaction Assay for Human Identity Testing. Genome Sci. Technol. 1996, 1, 77–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, D.J.; Speiser, P.W.; White, P.C.; Barany, F. Detection of Steroid 21-Hydroxylase Alleles Using Gene-Specific PCR and a Multiplexed Ligation Detection Reaction. Genomics 1995, 29, 152–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Granger, K.; Rundell, M.; Pingle, M.; Shatsky, R.; Larone, D.; Golightly, L.; Barany, F.; Spitzer, E. Multiplex PCR-ligation detection reaction assay for simultaneous detection of drug resistance and toxin genes from Staphylococcus aureus, Enterococcus faecalis, and Enterococcus faecium. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2010, 48, 277–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pingle, M.R.; Granger, K.; Feinberg, P.; Shatsky, R.; Sterling, B.; Rundell, M.; Spitzer, E.; Larone, D.; Golightly, L.; Barany, F. Multiplexed identification of blood-borne bacterial pathogens by use of a novel 16S rRNA gene PCR-ligase detection reaction-capillary electrophoresis assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 1927–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomas, G.; Sinville, R.; Sutton, S.; Farquar, H.; Hammer, R.P.; Soper, S.A.; Cheng, Y.W.; Barany, F. Capillary and microelectrophoretic separations of ligase detection reaction products produced from low-abundant point mutations in genomic DNA. Electrophoresis 2004, 25, 1668–1677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Chen, Z.; Zhao, Y.; Guo, J.-x.; Fu, H.; Zhou, Y.-g.; Yu, L.-l.; Li, L. PCR/LDR/capillary electrophoresis for detection of single-nucleotide differences between fetal and maternal DNA in maternal plasma. Prenat. Diagn. 2009, 29, 217–222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, P.; Chen, Z.; Yu, L.; Zheng, Y.; Liu, G.; Xie, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Han, J.; Li, L. Development of a PCR/LDR/capillary electrophoresis assay with potential for the detection of a beta-thalassemia fetal mutation in maternal plasma. J. Matern.-Fetal Neonatal Med. 2010, 23, 920–927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikhailovich, V.; Lapa, S.; Gryadunov, D.; Sobolev, A.; Strizhkov, B.; Chernyh, N.; Skotnikova, O.; Irtuganova, O.; Moroz, A.; Litvinov, V.; et al. Identification of Rifampin-Resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis Strains by Hybridization, PCR, and Ligase Detection Reaction on Oligonucleotide Microchips. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2001, 39, 2531–2540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Busti, E.; Bordoni, R.; Castiglioni, B.; Monciardini, P.; Sosio, M.; Donadio, S.; Consolandi, C.; Rossi Bernardi, L.; Battaglia, C.; De Bellis, G. Bacterial discrimination by means of a universal array approach mediated by LDR (ligase detection reaction). BMC Microbiol. 2002, 2, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerry, N.P.; Witowski, N.E.; Day, J.; Hammer, R.P.; Barany, G.; Barany, F. Universal DNA microarray method for multiplex detection of low abundance point mutations. J. Mol. Biol. 1999, 292, 251–262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Pingle, M.R.; Muñoz-Jordán, J.; Rundell, M.S.; Rondini, S.; Granger, K.; Chang, G.J.; Kelly, E.; Spier, E.G.; Larone, D.; et al. Detection and serotyping of dengue virus in serum samples by multiplex reverse transcriptase PCR-ligase detection reaction assay. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 3276–3284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rondini, S.; Pingle, M.R.; Das, S.; Tesh, R.; Rundell, M.S.; Hom, J.; Stramer, S.; Turner, K.; Rossmann, S.N.; Lanciotti, R.; et al. Development of Multiplex PCR-Ligase Detection Reaction Assay for Detection of West Nile Virus. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2008, 46, 2269–2279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaffney, R.; Chakerian, A.; O’Connell, J.X.; Mathers, J.; Garner, K.; Joste, N.; Viswanatha, D.S. Novel Fluorescent Ligase Detection Reaction and Flow Cytometric Analysis of SYT-SSX Fusions in Synovial Sarcoma. J. Mol. Diagn. 2003, 5, 127–135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carnevale, E.P.; Kouri, D.; DaRe, J.T.; McNamara, D.T.; Mueller, I.; Zimmerman, P.A. A multiplex ligase detection reaction-fluorescent microsphere assay for simultaneous detection of single nucleotide polymorphisms associated with Plasmodium falciparum drug resistance. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2007, 45, 752–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Barany, F.; Soper, S.A. Polymerase chain reaction/ligase detection reaction/hybridization assays using flow-through microfluidic devices for the detection of low-abundant DNA point mutations. Biosens. Bioelectron. 2006, 21, 1915–1923. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huh, Y.S.; Lowe, A.J.; Strickland, A.D.; Batt, C.A.; Erickson, D. Surface-Enhanced Raman Scattering Based Ligase Detection Reaction. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2009, 131, 2208–2213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashimoto, M.; Morimoto, C.; Hagihara, K.; Tsukagoshi, K. Rapid and Convenient Sample Preparation in a Single Tube Using Magnetic Beads for Fluorescence Detection of Single Nucleotide Variation Based on Oligonucleotide Ligation. Chem. Lett. 2012, 41, 135–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Pei, L.; Xia, H.; Tang, Q.; Bi, F. Role of oncogenic KRAS in the prognosis, diagnosis and treatment of colorectal cancer. Mol. Cancer 2021, 20, 143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, X.; Smith, L. Solid-phase method for the purification of DNA sequencing reactions. Anal. Chem. 1992, 64, 2672–2677. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyre, D.E.; Le Trong, I.; Merritt, E.A.; Eccleston, J.F.; Green, N.M.; Stenkamp, R.E.; Stayton, P.S. Cooperative hydrogen bond interactions in the streptavidin–biotin system. Protein Sci. 2006, 15, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

| Primer Name | Usage | Sequence (5′→3′) | Size (mer) |

|---|---|---|---|

| KRAS exon 2 forward | Primer for PCR | TTAAAAGGTACTGGTGGAGTATTTGATA | 28 |

| KRAS exon 2 reverse | Primer for PCR | AAAATGGTCAGAGAAACCTTTATCTGT | 27 |

| KRAS c.35A-HEX | Discrim. primer for LDR | HEX-AAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGAGCTGA | 23 |

| KRAS c.35T-TAMRA | Discrim. primer for LDR | TAMRA-AAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGAGCTGT | 23 |

| KRAS c.35G(WT)-ROX | Discrim. primer for LDR | ROX-AAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGAGCTGG | 23 |

| KRAS c.35C-Alexa Fluor 647 | Discrim. primer for LDR | Alexa Fluor 647-AAACTTGTGGTAGTTGGAGCTGC | 23 |

| KRAS c.36T Com-2/3′-biotin | Com. primer for LDR | pTGGCGTAGGCAAGAGTGCCT-biotin | 20 |

| LDR template for p.G12D | Synthetic template for LDR | AGGCACTCTTGCCTACGCCATCAGCTCCAACTACCACAAGTTT | 43 |

| LDR template for p.G12V | Synthetic template for LDR | AGGCACTCTTGCCTACGCCAACAGCTCCAACTACCACAAGTTT | 43 |

| LDR template for p.G12G(WT) | Synthetic template for LDR | AGGCACTCTTGCCTACGCCACCAGCTCCAACTACCACAAGTTT | 43 |

| LDR template for p.G12A | Synthetic template for LDR | AGGCACTCTTGCCTACGCCAGCAGCTCCAACTACCACAAGTTT | 43 |

| Cell Line | Nucleotide Change | Amino Acid Change | Zygosity | Genotype |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| LS180 | c.35G>A | p.G12D | Heterozygous | G/A |

| SW620 | c.35G>T | p.G12V | Homozygous | T/T |

| HT-29 | c.35G (WT) | p.G12G | Homozygous | G/G |

| SW1116 | c.35G>C | p.G12A | Heterozygous | G/C |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Morimoto, C.; Hashimoto, M. Fluorescence-Based Detection of KRAS Mutations in Genomic DNA Using Magnetic Bead-Coupled LDR Assay. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060142

Morimoto C, Hashimoto M. Fluorescence-Based Detection of KRAS Mutations in Genomic DNA Using Magnetic Bead-Coupled LDR Assay. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):142. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060142

Chicago/Turabian StyleMorimoto, Chika, and Masahiko Hashimoto. 2025. "Fluorescence-Based Detection of KRAS Mutations in Genomic DNA Using Magnetic Bead-Coupled LDR Assay" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060142

APA StyleMorimoto, C., & Hashimoto, M. (2025). Fluorescence-Based Detection of KRAS Mutations in Genomic DNA Using Magnetic Bead-Coupled LDR Assay. Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 142. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060142