Major Antioxidants and Methods for Studying Their Total Activity in Milk: A Review

Abstract

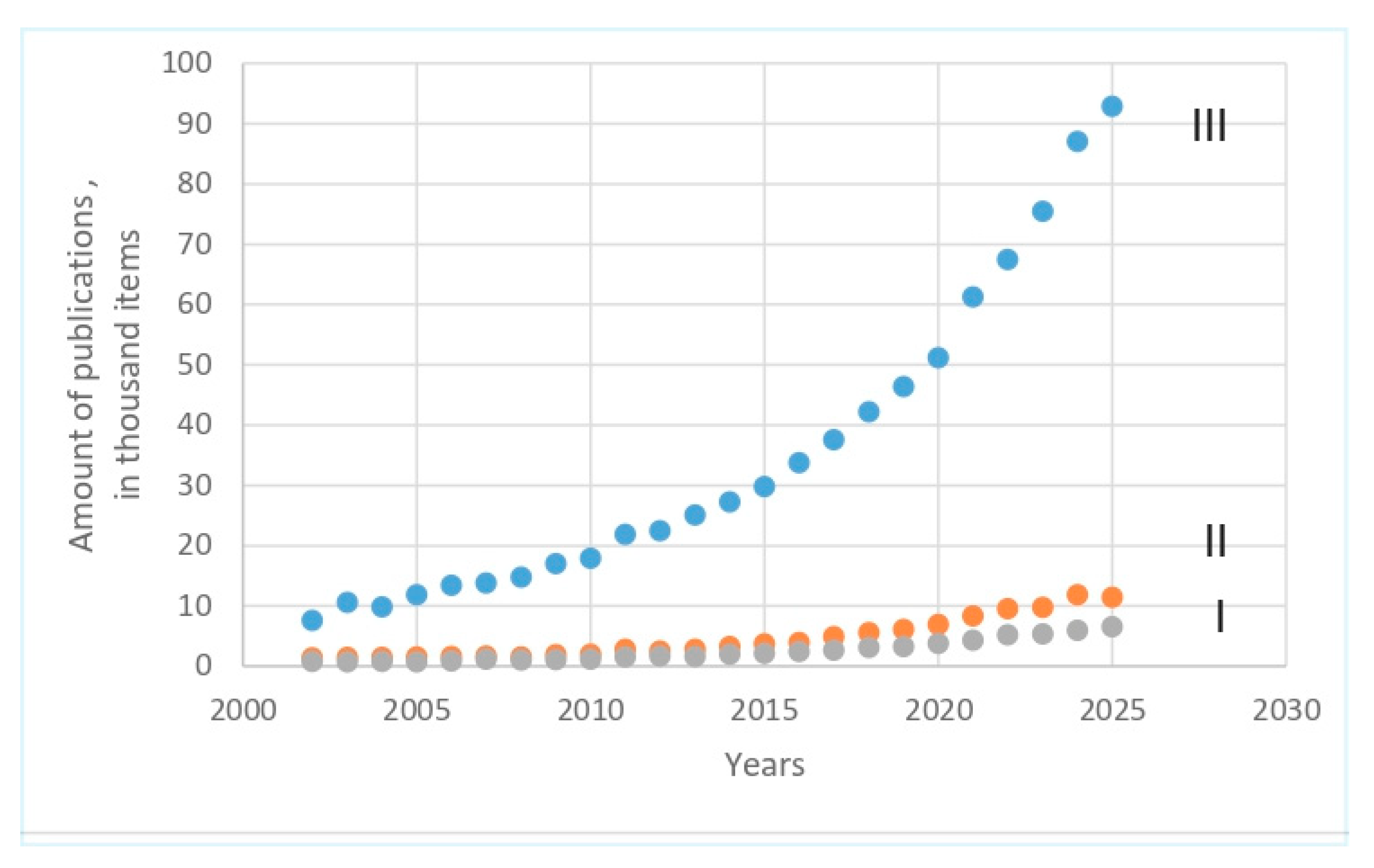

1. Introduction

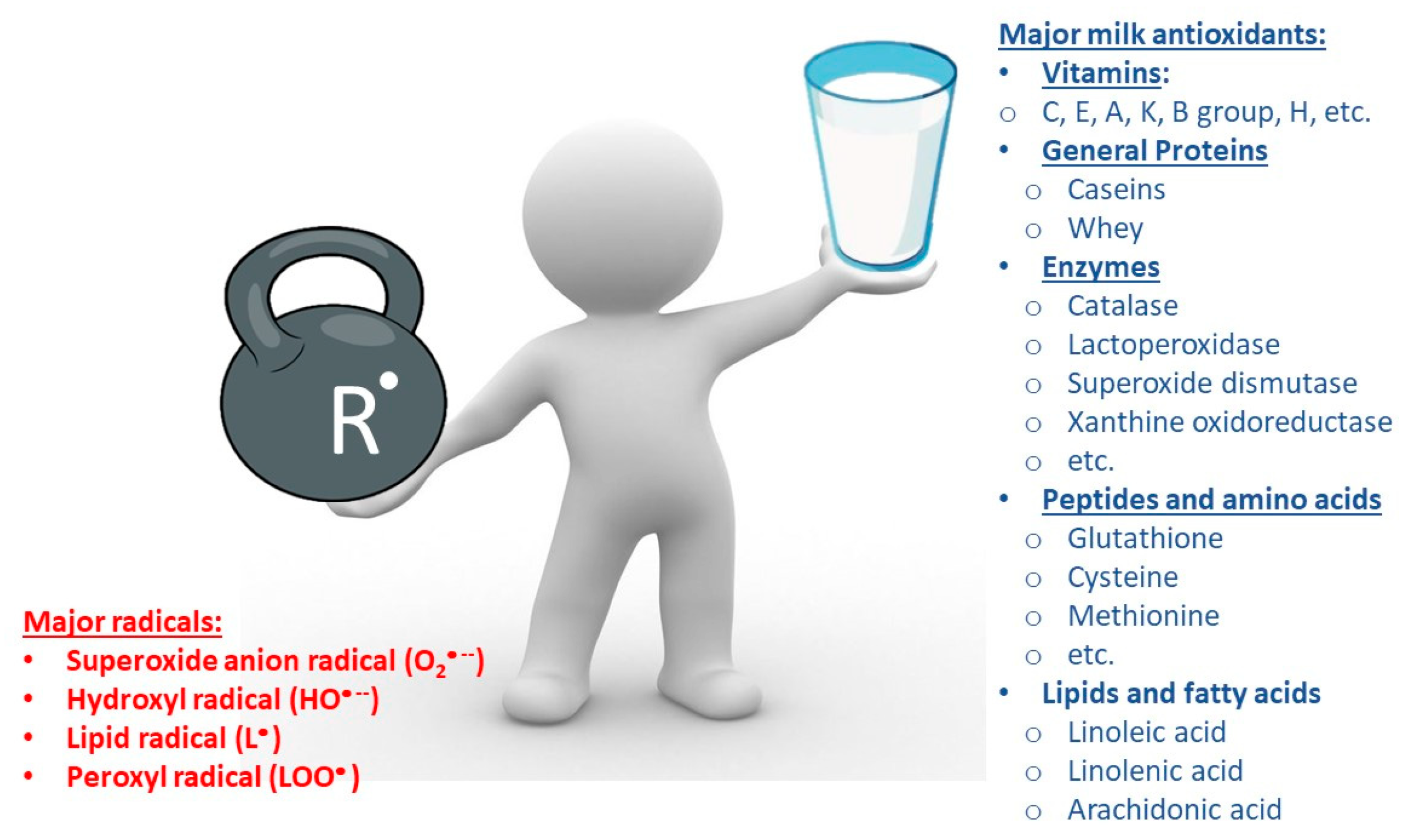

2. General Approaches to the Classification of Various Antioxidants

3. Vitamins, Provitamins, and Derivatives

3.1. Ascorbic Acid (Vitamin C) as the Major Water-Soluble Vitamin in Milk

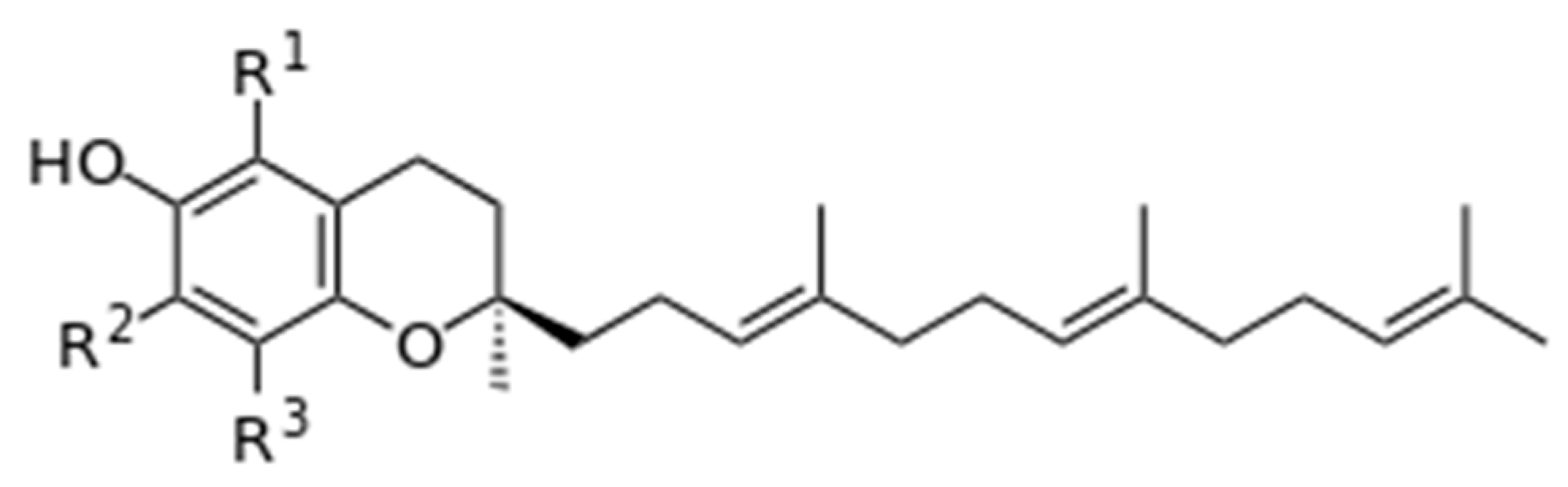

3.2. Tocopherols (Vitamin E) as the Main Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Milk

3.3. Some Other Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Bovine Milk

3.4. Some Other Water-Soluble Vitamins in Bovine Milk

3.5. Vitamin Requirements of Dairy Cows and Pathologies Associated with Vitamin Deficiency

4. Milk Proteins, Carbohydrates, and Lipids

4.1. Caseins

4.2. Whey Proteins

4.2.1. Lactoferrin

4.2.2. Catalase

4.2.3. Superoxide Dismutase

4.2.4. Glutathione Peroxidase

4.2.5. Lactoperoxidase

4.2.6. Ceruloplasmin

4.2.7. Xanthine Oxidase

4.2.8. Sulfhydryl Oxidases

4.3. Milk Peptides and Amino Acids

4.3.1. Peptides with More than Six Amino Acids

4.3.2. Tripeptide Glutathione

4.3.3. Milk Amino Acids

4.4. Carbohydrates

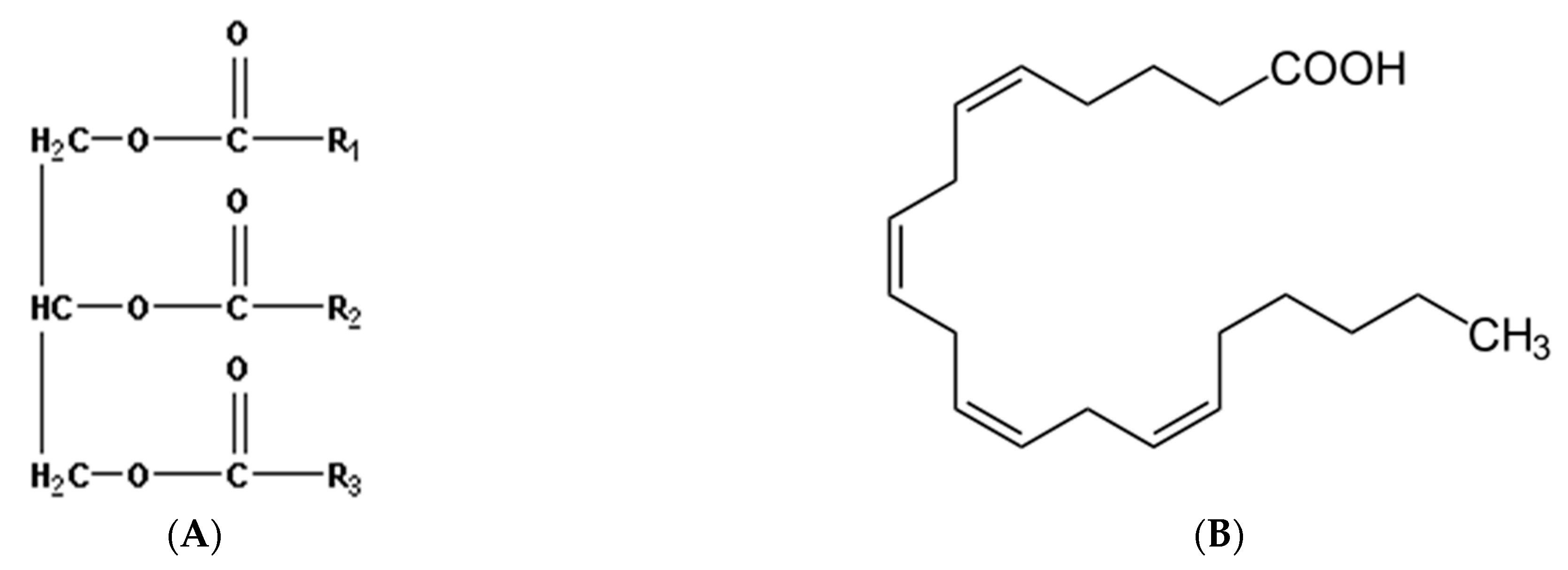

4.5. Lipids

4.6. Final Remarks on Part 4

5. Methods for Studying the Antioxidant Activity of Various Biological Objects

5.1. “Ox–Red” Titration

5.2. Spectroscopic Methods

5.2.1. “FRAP” Method

5.2.2. “CUPRAC” and “CRAC” Methods

5.2.3. “DPPH” and “ABTS” Methods

5.3. Coulometric Method

5.4. Voltammetric and Potentiometric Methods

5.5. Amperometric Method for Studying the Total Antioxidant Activity of Milk

6. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Roy, D.; Ye, A.; Moughan, P.J.; Singh, H. Composition, Structure, and Digestive Dynamics of Milk From Different Species—A Review. Front. Nutr. 2020, 7, 577759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Voronina, O.A.; Kolesnik, N.S.; Sivkina, O.N.; Sermyagin, A.A.; Osadchaya, O.Y. Biochemical and Physicochemical Methods for Studying Cow’s Milk; Federal Research Center for Animal Husbandry named after Academy Member L.K. Ernst: Dubrovitsy, Russia, 2024; 392p.

- Walstra, P.; Walstra, P.; Wouters, J.T.; Geurts, T.J. Dairy Science and Technology, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 2006; 808р. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, S.; Harte, F. Raw Milk: Nature’s most perfect food? In Encyclopedia of Dairy Sciences, 3rd ed.; Elsevier: Philadelphia, PA, USA, 2021; Volume 5, pp. 451–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Food Outlook—Biannual Report on Global Food Markets; Food Outlook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025; 152p. [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Fedorova, E.Y.; Maximov, V.I. Comprehensive Analysis of the Major ATPase Activities in the Cow Milk and Their Correlations. BioNanoScience 2019, 9, 386–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidlovskaya, V.P.; Yurova, E.A. Antioxidants of milk and their role in evaluating its quality. Dairy Ind. 2010, 2, 24–27. [Google Scholar]

- Stobiecka, M.; Król, J.; Brodziak, A. Antioxidant Activity of Milk and Dairy Products. Animals 2022, 12, 245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khan, I.T.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Ullah, R.; Ajmal, M.; Jaspal, M.H. Antioxidant properties of Milk and dairy products: A comprehensive review of the current knowledge. Lipids Health Dis. 2019, 18, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, A.A.; Voronina, O.A.; Bogolyubova, N.V.; Zaitsev, S.Y. Amperometric detection of the antioxidant activity of model and biological fluids. Mosc. Univ. Bulletin. Ser. 2 Chem. 2020, 75, 340–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Voronina, O.A.; Savina, A.A.; Ignatieva, L.P.; Bogolyubova, N.V. Correlations between the Total Antioxidant Activity and Biochemical Parameters of Cow Milk Depending on the Number of Somatic Cells. Int. J. Food Sci. 2022, 2022, 5323621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.A.; Zaitsev, S.Y.; Savina, A.A.; Rykov, R.A.; Kolesnik, N.S. Seasonal Changes in the Antioxidant Activity and Biochemical Parameters of Goat Milk. Animals 2023, 13, 1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsen, S.Y.; Siew, J.; Lau, E.K.L.; Afiqahbte Roslee, F.; Chan, H.M.; Loke, W.M. Cow’s milk as a dietary source of equol and phenolic antioxidants: Differential distribution in the milk aqueous and lipid fractions. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2014, 94, 625–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simos, Y.; Metsios, A.; Verginadis, I.; Alessandro, A. Antioxidant and anti-platelet properties of milk from goat, donkey and cow: An in vitro, ex vivo and in vivo study. Int. Dairy J. 2011, 21, 901–906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamed, H.; Feki, A.E.; Gargouri, A. Total and differential bulk cow milk somatic cell counts and their relation with antioxidant factors. Comptes Rendus Biol. 2008, 331, 144–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Lindmark-Månsson, H.; Gorton, L.; Åkesson, B. Antioxidant capacity of bovine milk as assayed by spectrophotometric and amperometric methods. Int. Dairy J. 2003, 13, 927–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niero, G.; Penasa, M.; Costa, A.; Currò, S.; Visentin, G.; Cassandro, M.; De Marchi, M. Total antioxidant activity of bovine milk: Phenotypic variation and predictive ability of mid-infrared spectroscopy. Int. Dairy J. 2019, 89, 105–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yashin, Y.I.; Ryzhnev, V.Y.; Yashin, A.Y.; Chernousova, N.I. Natural Antioxidants. Content in Food Products and Their Impact on Human Health and Aging; Publishing house “TransLit”: Moscow, Russia, 2009; 212p. [Google Scholar]

- Dobriyan, E.I. Antioxidant system of milk. Bull. Voronezh State Univ. Eng. Technol. 2020, 82, 101–106. [Google Scholar]

- Rudakov, O.; Rudakova, L.V. Amino acid analysis of milk proteins. Milk Branch Mag. 2019, 12, 32–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindmark-Mansson, H.; Akesson, B. Antioxidative factors in milk. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 84 (Suppl. 1), S103–S110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodionov, G.V.; Ostroukhova, V.I.; Tabakova, L.P. Technology of Production and Quality Assessment of Milk; Publishing house “Lan”: Moscow, Russia, 2018; 136p. [Google Scholar]

- Bogatova, O.V.; Dogareva, N.G. Chemistry and Physics of Milk; Publishing house “GOU OSU”: Orenburg, Russia, 2004; 137p. [Google Scholar]

- Tverdokhleb, G.V.; Ramanauskas, R.I. Chemistry and Physics of Milk and Dairy Products; Publishing house “DeLi print”: Moscow, Russia, 2006; 260p. [Google Scholar]

- Savina, A.A.; Voronina, D.A.; Zaitsev, S.Y. Seasonal patterns of changes in antioxidant and microelement parameters of milk from black-and-white cows. Agric. Sci. Euro-North-East 2023, 24, 858–867. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidlovskaya, V.P.; Yurova, E.A. Antioxidant activity of enzymes. Dairy Ind. 2011, 12, 48–49. [Google Scholar]

- Aliev, A.A. Metabolism in Ruminants; Research Center “Engineer”: Moscow, Russia, 1997; 419p. (In Russian) [Google Scholar]

- Toepel, A. Chemie und Physik der Milch (Chemistry and Physics of Milk), 3rd ed.; Behr’s Verlag: Hamburg, Germany, 2004; 756p. [Google Scholar]

- Bylund, G. Dairy Processing Handbook; Tetra Pak Processing Systems AB: Lund, Sweden, 1995. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev, S.Y. Biological Chemistry: From Biologically Active Substances to Organs and Tissues of Animals; Publishing house “Capital Print”: Moscow, Russia, 2017; 517p. [Google Scholar]

- Choe, E.; Min, D.B. Mechanisms of antioxidants in the oxidation of foods. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. Comp Rev Food Sci Food Saf. 2009, 4, 345–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fomichev, Y.P.; Khripyakova, E.N.; Gudenko, N.D. Methodological Practical Training on Quality Control of Milk and Dairy Products; VIZh im. L.K. Ernst: Dubrovitsy, Russia, 2013; 236p. [Google Scholar]

- Milk and Dairy Products in Human Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2013; 376р, Available online: http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/i3396e (accessed on 9 April 2025).

- Öste, R.; Jägerstad, M.; Andersson, I. Vitamins in Milk and Milk Products. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry, 2nd, ed.; Fox, P.F., Ed.; Publishing house “Springer”: New York, NY, USA, 1997; Volume 3, Chapter 9; pp. 347–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andersson, I.; Öste, R. Nutritional quality of pasteurized milk. Vitamin B12, folacin and ascorbic acid content during storage. Int. Dairy J. 1994, 4, 161–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilic, N. Assay for both ascorbic and dehydroascorbic acid in dairy foods by high-performance liquid chromatography using precolumn derivatization with methoxy- and ethoxy-1,2-phenylenediamine. J. Chromatogr. 1991, 543, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pizzoferrato, L. Examples of direct and indirect effects of technological treatments on ascorbic acid, folate and thiamine. Food Chem. 1992, 1, 49–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vahcic, N.; Palic, A.; Ritz, M. Mathematical evaluation of relationships between copper, iron, ascorbic acid and redox potential of milk. Milchwissenschaft 1992, 47, 228–230. [Google Scholar]

- Andersson, I.; Öste, R. Loss of ascorbic acid, folacin and vitamin B12, and changes in oxygen content of UHT milk. II. Results and discussion. Milchwissenschaft 1992, 47, 299–302. [Google Scholar]

- Król, J.; Wawryniuk, A.; Brodziak, A.; Barłowska, J.; Kuczy’nska, B. The effect of selected factors on the content of fat-soluble vitamins and macro-elements in raw milk from Holstein–Friesian and Simmental cows and acid curd cheese (tvarog). Animals 2020, 10, 1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharipova, L.Z.; Shcherbakova, Y.V.; Akhmadullina, F.Y. The influence of pasteurization on vitamin C in cow and goat milk. Bull. Kazan Technol. Univ. 2013, 16, 213–215. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_20463338_20942056.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Gorbatova, K.K.; Gunkova, P.I. Biochemistry of Milk and Dairy Products, 4th ed.; Publishing house “GIORD”: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2010; 330p. [Google Scholar]

- Ryabova, A.E.; Pryanichnikova, N.S.; Khurshudyan, S.A. Dairy Industry of Russia: Realities in Historical Context; Publishing house “VNIMI”: Moscow, Russia, 2022; 163p. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev, S.Y. Interfacial tensiometry method for the analysis of model systems in comparison with blood as the most important biological liquid. Moscow Univ. Chem. Bull. 2016, 71, 205–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Aardt, M.; Duncan, S.E.; Marcy, J.E.; Long, T.E.; O’Keefe, S.F.; Nielsen-Sims, S.R. Aroma analysis of light-exposed milk stored with and without natural and synthetic antioxidants. J. Dairy Sci. 2005, 88, 881–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whited, L.J.; Hammond, B.H.; Chapman, K.W.; Boor, K.J. Vitamin A degradation and light oxidized flavor defects in milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2002, 85, 351–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razumovsky, N.; Sobolev, D. Vitamin E—An important nutritional element. Anim. Husb. Russ. 2017, 49–51. Available online: https://static.zzr.ru/public/article/pdf/zzr-2017-02-015.pdf (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Bilic, N.; Sieber, R. Bestimmung von Retinol und alpha-Tocopherol in Milch und Milchprodukten mit Hilfe der Hochdruck-Flüssigchromatographie (HPLC) nach Verseifung in Serumfläschchen [Determination of retinol and alpha-tocopherol in milk and milk products using high-pressure liquid chromatography after saponification in serum vials]. Z. Für Lebensm. Unters. Und-Forsch. 1988, 186, 514–518. (In Germany) [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Jensen, S.K.; Nielsen, K.N. Tocopherols, retinol, β-carotene and fatty acids in fat globule membrane and fat globule core in cow’s milk. J. Dairy Res. 1996, 63, 565–574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Milaeva, I.V.; Tsarkova, M.S. Biochemical and Physicochemical Parameters of Milk; Moscow SAVMB: Moscow, Russia, 2017; 41p. [Google Scholar]

- Zaitsev, S.Y. Antioxidant Activity of Milk; VIZh im. Ernst: Dubrovitsy, Russia, 2022; 56p. [Google Scholar]

- Kalnitsky, B.D. Methods of Biochemical Analysis: A Reference Manual; VNIIFBiP: Borovsk, Russia, 1997; 221p. [Google Scholar]

- Reshetov, V.B. Farm Animals. Physiological and Biochemical Parameters of the Body. Reference Manual; VNIIFBiP: Borovsk, Russia, 2002; 354p. [Google Scholar]

- Gusev, I.V.; Bogolyubova, N.V. (Eds.) Monitoring the Biochemical Status of Pigs And Cows: Manual; VIZh im. L.K. Ernst: Dubrovitsy, Russia, 2019; 40p. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R.G. Fat-Soluble Vitamins in Bovine Milk. In Handbook of Milk Composition; Robert, G.J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; Chapter 8-E; pp. 718–725. [Google Scholar]

- Hidiroglou, M. Mammary transfer of vitamin E in dairy cows. J. Dairy Sci. 1989, 72, 1067–1071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calderon, F.; Chauveau-Duriot, B.; Martin, B.; Graulet, B.; Doreau, M.; Noziere, P. Variations in Carotenoids, Vitamins A and E, and Color in Cow’s Plasma and Milk During Late Pregnancy and the First Three Months of Lactation. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 90, 2335–2346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Syväoja, E.L.; Piironen, V.; Varo, P.; Koivistoinen, P.; Salminen, K. Tocopherols and tocotrienols in Finnish foods: Human milk and infant formulas. Int. J. Vitam. Nutr. Res. 1985, 55, 159–166. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Scott, K.J.; Bishop, D.R.; Zechalko, A.; Edwards-Webb, J.D.; Jackson, P.A.; Scuffam, D. Nutrient content of liquid milk: I. Vitamins A, D3, C and of the B complex in pasteurized bulk liquid milk. J. Dairy Res. 1984, 51, 37–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolton-Smith, C.; Price, R.; Fenton, S.; Harrington, D.; Shearer, M. Compilation of a provisional UK database for the phylloquinone (vitamin K1) content of foods. Br. J. Nutr. 2000, 83, 389–399. [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, R.G. Water-soluble vitamins in bovine milk. In Handbook of Milk Composition; Robert, G.J., Ed.; Academic Press: San Diego, CA, USA, 1995; Chapter 8-B; pp. 688–692. [Google Scholar]

- Renner, E.; Schaafsma, G.; Scott, K.J. Micronutrients in milk. In Micronutrients in Milk and Milk-Based Food Products; Renner, E., Ed.; Elsevier Applied Science Publishers Ltd.: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- FAO; IFAD; UNICEF; WFP; WHO. The State of Food Security and Nutrition in the World. 2025—Addressing High Food Price Inflation for Food Security and Nutrition; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD-FAO Agricultural Outlook 2025-2034. Available online: https://chooser.crossref.org/?doi=10.1787%2F601276cd-en (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- World Food and Agriculture—Statistical Yearbook; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2023.

- FAO. Transforming Food and Agriculture Through a Systems Approach; FAO: Rome, Italy, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trukhachev, V.I.; Kapustin, I.V.; Zlydnev, N.Z.; Kapustina, E.I. Milk: State and Problems of Production; Publishing house “Lan”: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2018; 300p. [Google Scholar]

- Zimnyakov, V.M.; Ilyina, G.V.; Ilyin, D.Y.; Zimnyakov, A.M. The state, problems and prospects of milk production in Russia. Mach. Technol. Livest. 2023, 49, 4–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cherepanov, G.G.; Kharitonov, E.L.; Mikhalsky, A.I.; Novoseltseva, Z.A. Analysis of possible approaches to overcome the antagonism between the level of productivity and viability of breeding stock when using intensive technologies. Probl. Biol. Product. Anim. 2017, 5–27. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_28777491_18835427.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Kharitonov, E.L. Physiology and Biochemistry of Cattle Nutrition; “Ortima Press”: Borovsk, Russia, 2011; 372p. [Google Scholar]

- Kharitonov, E.L. Experimental and Applied Physiology of Digestion of Ruminants; Federal Research Center for Animal Husbandry named after Academy Member L.K. Ernst: Dubrovitsy, Russia, 2019.

- Kharitonov, E.L. The analysis of fodder diets for highly productive dairy cattle of various regions of the country. Dairy Beef Cattle Breed. 2012, 11–15. Available online: http://bifip.ru/attachments/article/246/21.3-82-91.pdf (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Bendich, A. Physiological role of antioxidants in the immune system. J. Dairy Sci. 1993, 76, 2789–2794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ostapchuk, P.S.; Zubochenko, D.V.; Kuevda, T.A. The role of antioxidants and their use in animal breeding and poultry farming (review). Agric. Sci. Euro-North-East 2019, 20, 103–117. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogatirev, A.B.; Emelyanov, S.A.; Skorykh, L.N.; Konik, N.V.; Kolotova, N.A. New principles for ensuring the biological safety of raw materials and products of animal origin. Res. J. Pharm. Biol. Chem. Sci. 2018, 9, 1106–1109. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/download/elibrary_23600062_90522591.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Benzie, I.F.F. Evolution of dietary antioxidants. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. A Mol. Integr. Physiol. 2003, 136, 113–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Salami, S.; Guinguina, A.; Agboola, J.; Omede, A.; Agbonlahor, E.; Tayyab, U. Review: In vivo and postmortem effects of feed antioxidants in livestock: A review of the implications on authorization of antioxidant feed additives. Animal 2016, 10, 1375–1390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carocho, M.; Ferreira, I.C.F.R. A review on antioxidants, prooxidants and related controversy: Natural and synthetic compounds, screening and analysis methodologies and future perspectives. Food Chem. Toxicol. 2013, 51, 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahl, R. Synthetic antioxidants: Biochemical actions and interference with radiation, toxic compounds, chemical mutagens and chemical carcinogens. Toxicology 1984, 33, 185–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gregory, J.F., 3rd. Accounting for differences in the bioactivity and bioavailability of vitamers. Food Nutr. Res. 2012, 56, 5809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Subroto, E.; Putri, N.G.; Rahmani, F.R.; Nuramalia, A.F.; Musthafa, D.A. Bioavailability and Bioactivity of Vitamin C. A Review. Int. J. Pharm. Res. 2021, 13, 128–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jakobsen, J. Bioavailability and bioactivity of vitamin D3 active compounds—Which potency should be used for 25-hydroxyvitamin D3? Int. Congr. Ser. 2007, 1297, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Augustiniak, A.; Bartosz, G.; Cipak, A.; Dubus, G.; Horáková, L.; Łuczaj, W.; Májeková, M.; Odysseos, A.; Racková, L.; Skrzydlewska, E.; et al. Natural and synthetic antioxidants: An updated overview. Free. Radic. Res. 2010, 44, 1216–1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Surai, P.; Fisinin, V.I. Antioxidant-Prooxidant Balance in the Intestine: Applications in Chick Placement and Pig Weaning. J. Veter. Sci. Med. 2015, 3, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palozza, P. Pro-oxidant actions of carotenoids in biologic systems. Nutr. Rev. 1998, 56, 257–265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Davies, K.J. Oxidative stress: The paradox of aerobic life. Biochem. Soc. Symp. 1995, 61, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliwell, B. Free radicals and antioxidants—Quo vadis? Trends Pharmacol. Sci. 2011, 32, 125–130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nijveldt, R.J.; van Nood, E.; van Hoorn, D.E.C.; Boelens, P.G.; van Norren, K.; van Leeuwen, P.A.M. Flavonoids: A review of probable mechanisms of action and potential applications. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 74, 418–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moghadam, S.K. Antioxidants Capacity of Milk, Probiotics and Postbiotics: A Review. Food Sci. Nutr. Tech. 2024, 9, 000327. [Google Scholar]

- Wiseman, E.M.; Bar-El Dadon, S.; Reifen, R. The vicious cycle of vitamin a deficiency: A review. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 57, 3703–3714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olson, J.A. Requirements and safety of vitamin A in humans. In Vitamin A and Retinoids: An Update of Biological Aspects and Clinical Applications, Livrea, M.A., Ed.; Birkhäuser: Basel, Switzerland, 2000; pp. 29–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sommer, A. Vitamin A Deficiency And Its Consequences. A Field Guide to Detection and Control, 3rd ed.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1995; 69p, ISBN 92415447783. [Google Scholar]

- Sarwar, M.F.; Sarwar, M.H.; Sarwar, M. Deficiency of Vitamin B-Complex and Its Relation with Body Disorders. In the “B-Complex Vitamins—Sources, Intakes and Novel Applications”; Guy LeBlanc, J., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hanna, M.; Jaqua, E.; Nguyen, V.; Clay, J. B Vitamins: Functions and Uses in Medicine. Perm J. 2022, 26, 89–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paez-Hurtado, A.M.; Cortes-Albornoz, M.C.; Rodríguez-Gomez, D.A.; Calderón-Ospina, C.-A.; Nava-Mesa, M.O. B vitamins on the nervous system: A focus on peripheral neuropathy. In Vitamins and Minerals in Neurological Disorders; Colin, R.M., Vinood, B.P., Victor, R.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2023; Chapter 37; pp. 643–657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prakash, A. Vitamin C Deficiency: A Review. J. Rehabil. Res. Pract. 2021, 2, 17–20. Available online: https://www.probiologists.com/public/assets/articles/article-pdf-1734092174-199.pdf (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Halliwell, B. Vitamin C: Antioxidant or pro-oxidant in vivo? Free Radic. Res. 1996, 25, 439–454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsui, T. Vitamin C nutrition in cattle. Asian-Australas J. Anim. Sci. 2012, 25, 597–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxfield, L.; Crane, J.S. Vitamin C Deficiency; StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2021; Available online: http://europepmc.org/books/NBK493187 (accessed on 30 September 2025).

- Korhonen, H.J. Bioactive Components in Bovine Milk. In Bioactive Components in Milk and Dairy Products; Young, W.P., Ed.; Wiley-Blackwell: Singapore, 2009; Chapter 2; pp. 15–42. [Google Scholar]

- Fox, P.F. Milk Proteins: General and Historical Aspects. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry: Volume 1: Proteins, Parts A&B; Fox, P.F., McSweeney, P.L.H., Eds.; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2003; Chapter 1; pp. 1–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nayika, G.A.; Gullb, A.; Masoodib, L.; Navafc, M.; Sunoojc, K.V.; Ucakd, İ.; Afreend, M.; Kaure, P.; Rehalf, J.; Jagdaleg, Y.D.; et al. Milk proteins: Chemistry, functionality and diverse industrial applications. Cogent Food Agric. 2024, 10, 2377686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lucey, J.A.; Otter, D.; Horne, D.S. A 100-Year Review: Progress on the chemistry of milk and its components. J. Dairy Sci. 2017, 100, 9916–9932. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huppertz, T.; Fox, P.F.; Kelly, A.L. The caseins: Structure, stability, and functionality. In Proteins in Food Processing Elsevier; Yada, R.Y., Ed.; Woodhead Publishing: Delhi, India, 2018; pp. 50–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nadugala, B.H.; Pagel Charles, N.; Raynes, J.K.; Ranadheera, C.S.; Logan, A. The effect of casein genetic variants, glycosylation and phosphorylation on bovine milk protein structure, technological properties, nutrition and product manufacture. Int. Dairy J. 2022, 133, 105440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhat, M.Y.; Dar, T.A.; Singh, L.R. Casein proteins: Structural and functional aspects. In Milk Proteins—From Structure to Biological Properties and Health Aspects; Gigli, I., Ed.; IntechOpen Limited: London, UK, 2016; pp. 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biasutti, E.A.R.; Vieira, C.R.; Capobiango, M.; Silva, V.D.M.; Silvestre, M.P.C. Study of some functional properties of casein: Effect of pH and tryptic hydrolysis. Int. J. Food Prop. 2007, 10, 173–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broyard, C.; Gaucheron, F. Modifications of structures and functions of caseins: A scientific and technological challenge. Dairy Sci. Technol. 2015, 95, 831–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carr, A.; Golding, M. Functional milk proteins production and utilization: Casein- based ingredients. In Advanced Dairy Chemistry; McSweeney, P., O’Mahony, J., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2016; pp. 35–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, B.G.; Cheng, N.; Kapoor, R.; Meletharayil, G.H.; Drake, M.A. Invited review: Microfiltration-derived casein and whey proteins from milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2021, 104, 2465–2479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atamer, Z.; Post, A.E.; Schubert, T.; Holder, A.; Boom, R.M.; Hinrichs, J. Bovine β-casein: Isolation, properties and functionality. A review. Int. Dairy J. 2017, 66, 115–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Bleeker, R.; Sala, G.; Meinders, M.B.J.; van Valenberg, H.J.F.; van Hooijdonk, A.C.M.; van der Linden, E. Particle size determines foam stability of casein micelle dispersions. Int. Dairy J. 2016, 56, 151–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holt, C.; De Kruif, C.G. Casein micelle structure, functions and interactions. Adv. Dairy Chem. 1 Proteins 2003, 1, 233–276. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Guo, R. pH-dependent structures and properties of casein micelles. Biophys. Chem. 2008, 136, 67–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Zhu, P.; Pang, X.; Xie, N.; Zhang, S.; Lv, J. Effect of different temperature-controlled ultrasound on the physical and functional properties of micellar casein concentrate. Foods 2021, 10, 2673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madureira, A.R.; Pereira, C.I.; Gomes, A.M.P.; Pintado, M.E.; Xavier Malcata, F. Bovine whey proteins—Overview on their main biological properties. Food Res. Int. 2007, 40, 1197–1211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minj, S.; Anand, S. Whey proteins and its derivatives: Bioactivity, functionality, and current applications. Dairy 2020, 1, 233–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinsella, J.E.; Whitehead, D.M. Proteins in whey: Chemical, physical, and functional properties. Advances 1989, 88, 2318–2328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelly, P. Whey protein ingredient applications. In Whey Proteins; Deeth, H.C., Bansal, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 335–375. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelegrine, D.H.G.; Gasparetto, C.A. Whey proteins solubility as function of temperature and pH. LWT—Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 38, 77–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R. Whey proteins in functional foods. In Whey Proteins; Deeth, H.C., Bansal, N., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 637–663. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adjonu, R.; Doran, G.; Torley, P.; Agboola, S. Whey protein peptides as components of nanoemulsions: A review of emulsifying and biological functionalities. J. Food Eng. 2014, 122, 15–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kell, D.B.; Heyden, E.L.; Pretorius, E. The biology of lactoferrin, an iron-binding protein that can help defend against viruses and bacteria. Front. Immunol. 2020, 11, 1221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Artym, J.; Zimecki, M. The role of lactoferrin in the proper development of newborns. Postep. Hig. I Med. Dosw. 2005, 59, 421–432. [Google Scholar]

- Baker, E.N.; Baker, H.M. Molecular structure, binding properties and dynamics of lactoferrin. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2005, 62, 2531–2539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taylor, S.; Brock, J.; Kruger, C.; Berner, T.; Murphy, M. Safety determination for the use of bovine milk-derived lactoferrin as a component of an antimicrobial beef carcass spray. Regul. Toxicol. Pharmacol. 2004, 39, 12–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomita, M.; Wakabayashi, H.; Shin, K.; Yamauchi, K.; Yaeshima, T.; Iwatsuki, K. Twenty-five years of research on bovine lactoferrin applications. Biochimie 2009, 91, 52–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babina, S.E.; Kanyshkova, T.G.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Lactoferrin is the major deoxyribonuclease of human milk. Biochemistry 2004, 69, 1006–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, B.F.; Baker, H.M.; Norris, G.E.; Rumball, S.V.; Baker, E.N. Apolactoferrin structure demonstrates ligand-induced conformational change in transferrins. Nature 1990, 344, 784–787. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soboleva, S.E.; Sedykh, S.E.; Alinovskaya, L.I.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Cow Milk Lactoferrin Possesses Several Catalytic Activities. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamauchi, K.; Wakabayashi, H.; Shin, K.; Takase, M. Bovine lactoferrin: Benefits and mechanism of action against infections. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2006, 84, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stelwagen, K.; Carpenter, E.; Haigh, B.; Hodgkinson, A.; Wheeler, T.T. Immune components of bovine colostrum and milk. J. Anim. Sci. 2009, 87 (Suppl. 13), 3–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kanwar, J.R.; Roy, K.; Patel, Y.; Zhou, S.F.; Singh, M.R.; Singh, D.; Nasir, M.; Sehgal, R.; Sehgal, A.; Singh, R.S. Multifunctional iron bound lactoferrin and nanomedicinal approaches to enhance its bioactive functions. Molecules 2015, 20, 9703–9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hill, D.R.; Newburg, D.S. Clinical applications of bioactive milk components. Nutr. Rev. 2015, 73, 463–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa, T.J.; Sizonenko, S.V. Lactoferrin and prematurity: A promising milk protein? Biochem. Cell Biol. 2017, 95, 22–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kanyshkova, T.G.; Buneva, V.N.; Nevinsky, G.A. Lactoferrin and its biological functions. Biochemistry 2001, 66, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cheng, J.B.; Wang, J.Q.; Bu, D.P.; Liu, G.L.; Zhang, C.G.; Wei, H.Y.; Zhou, L.Y.; Wang, J.Z. Factors Affecting the Lactoferrin Concentration in Bovine Milk. J. Dairy Sci. 2007, 91, 970–976. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karakus, Y.Y. Typical Catalases: Function and Structure. In Glutathione System and Oxidative Stress in Health and Disease; Dulce Bagatini, M., Ed.; IntechOpen: London, UK, 2020; Chapter 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mate, M.J.; Murshudov, G.; Bravo, J.; Melik-Adamyan, W.; Loewen, P.C.; Fita, I. Heme catalases. In Handbook of Metalloproteins; Messerschmidt, A., Huber, R., Poulos, T., Widghardt, K., Eds.; Wiley & Sons: Chichester, UK, 2001; pp. 486–502. [Google Scholar]

- Anwar, S.; Alrumaihi, F.; Sarwar, T.; Babiker, A.Y.; Khan, A.A.; Prabhu, S.V.; Rahmani, A.H. Exploring Therapeutic Potential of Catalase: Strategies in Disease Prevention and Management. Biomolecules 2024, 14, 697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silanikove, N.; Merin, U.; Leitner, G. Nitrite and catalase levels rule oxidative stability and safety properties of milk: A review. RSC Adv. 2014, 4, 26476–26486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farman, A.A.; Hadwan, M.H. Simple kinetic method for assessing catalase activity in biological samples. MethodsX 2021, 8, 101434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Savina, A.A.; Voronina, O.A.; Zaitsev, S.Y. Catalase activity in milk and its correlation with milk productivity of cows depending on the duration of lactation. Agrar. Sci. 2024, 1, 118–123. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, S.; Singh, D.; Patel, S.; Singh, M.R. Role of enzymatic free radical scavengers in management of oxidative stress in autoimmune disorders. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2017, 101, 502–517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sooch, B.S.; Kauldhar, B.S.; Puri, M. Recent insights into microbial catalases: Isolation, production and purification. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1429–1447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishikawa, M.; Hashida, M.; Takakura, Y. Catalase delivery for inhibiting ROS-mediated tissue injury and tumor metastasis. Adv. Drug Deliv. Rev. 2009, 61, 319–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Makievsky, A.V. Methods for studying the antioxidant activity of biological fluids. Agrochemical Bulletin. 2025, 2, 65–69. Available online: https://elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=80661094 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Ezema, B.O.; Eze, C.N.; Ayoka, T.O.; Nnadi, C.O. Antioxidant-enzyme Interaction in Non-communicable Diseases. J. Explor. Res. Pharmacol. 2024, 9, 262–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsatsulina, A.P.; Bocharova, K.V.; Ermakova, N.V. Study of catalase activity in cows’ milk. Sci. J. Young Sci. 2014, 28–29. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/izuchenie-aktivnosti-katalazy-v-moloke-korov (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Niklowitz, P.; Menke, T.; Giffei, J.; Andler, W. Coenzyme Q10 in maternal plasma and milk throughout early lactation. Biofactors 2005, 25, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Volykhina, V.E.; Shafranovskaya, E.V. Superoxide dismutases: Structure and properties. Bull. Vitebsk. State Med. Univ. 2009, 8, 6–12. Available online: https://elib.vsmu.by/handle/123/8288 (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Zelko, I.N.; Mariani, T.J.; Folz, R.J. Superoxide dismutase multigene family: A comparison of the Cu, Zn-SOD (SOD1), Mn-SOD (SOD2), and EC-SOD (SOD3) gene structures, evolution, and expression. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2002, 33, 337–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, J.; Starr, M.E.; Takahashi, H.; Du, J.; Chang, L.Y.; Crapo, J.D.; Evers, B.M.; Saito, H. Decreased pulmonary extracellular superoxide dismutase during systemic inflammation. Free Radic. Biol. Med. 2008, 45, 897–904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nozik-Grayck, E.; Suliman, H.B.; Piantadosi, C.A. Extracellular superoxide dismutase. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2005, 37, 2466–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Strålin, P.; Jacobsson, H.; Marklund, S.L. Oxidative stress, NO and smooth muscle cell extracellular superoxide dismutase expression. Biochim. Biophys. Acta. 2003, 1619, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wheeler, M.D.; Katuna, M.; Smutney, O.M.; Froh, M.; Dikalova, A.; Mason, R.P.; Samulski, R.J.; Thurman, R.G. Comparison of the effect of adenoviral delivery of three superoxide dismutase genes against hepatic ischemia-reperfusion injury. Hum. Gene Ther. 2001, 12, 2167–2177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kowluru, R.A.; Atasi, L.; Ho, Y.S. Role of mitochondrial superoxide dismutase in the development of diabetic retinopathy. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2006, 47, 1594–1599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, O.; Marklund, S.L.; Xia, N.; Busse, R.; Brandes, R.P. Inactivation of extracellular superoxide dismutase contributes to the development of high-volume hypertension. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol. 2007, 27, 470–477. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fujita, H.; Fujishima, H.; Chida, S.; Takahashi, K.; Qi, Z.; Kanetsuna, Y.; Breyer, M.D.; Harris, R.C.; Yamada, Y.; Takahashi, T. Reduction of renal superoxide dismutase in progressive diabetic nephropathy. J. Am. Soc. Nephrol. 2009, 20, 1303–1313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidlovskaya, V.P. Milk enzymes. In Handbook of a Dairy Production Technologist; GIORD: St. Petersburg, Russia, 2006; Volume 10, 296p. [Google Scholar]

- Matés, J.M.; Pérez-Gómez, C.; Blanca, M. Chemical and biological activity of free radical ‘scavengers’ in allergic diseases. Clin. Chim. Acta 2000, 296, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fox, P.F.; Kelly, A.L. Indigenous enzymes in milk: Overview and historical aspects—Part 2. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 517–532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, A.; Farré, R.; Lagarda, M.J.; Monleón, J. Determination of glutathione peroxidase activity in human milk. Nahrung 2003, 47, 430–433. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quiles, J.L.; Ochoa, J.J.; Ramirez-Tortosa, M.C.; Linde, J.; Bompadre, S.; Battino, M. Coenzyme Q concentration and total antioxidant capacity of human milk at different stage of lactation in mothers of preterm and full-term infants. Free Radic. Res. 2006, 40, 199–206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meister, A. On the antioxidant effects of ascorbic acid and glutathione. Biochem. Pharmacol. 1992, 44, 1905–1915. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tolpygina, O.A. The role of glutathione in the antioxidant defense system (review). Bull. East Sib. Sci. Cent. 2012, 2, 178–181. [Google Scholar]

- Özhan, H.K.; Duman, H.; Bechelany, M.; Karav, S. Lactoperoxidase: Properties, Functions, and Potential Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2025, 26, 5055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Singh, A.K.; Kaushik, S.; Sinha, M.; Singh, R.P.; Sharma, P.; Sirsohi, H.; Kaur, P.; Singh, T.P. Lactoperoxidase: Structural Insights into the Function, Ligand Binding and Inhibition. Int. J. Biochem. Mol. Biol. 2013, 4, 108–218. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson, L.M.; Sumner, S.S. Antibacterial Activity of The Lactoperoxidase System: A review. J. Food Prot. 1993, 56, 887–892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koksal, Z.; Gulcin, I.; Ozdemir, H. An Important Milk Enzyme: Lactoperoxidase. In Milk Proteins—From Structure to Biological Properties and Health Aspects; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Reiter, B. Lactoperoxidase System of Bovine Milk. In The Lactoperoxidase System: Chemistry and Biological Significance; Pruitt, K.M., Tenovuo, J.O., Eds.; Marcel Dekker: New York, NY, USA, 1985; pp. 123–141. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, K.; Hayasawa, H.; Lönnerdal, B. Purification and Quantification of Lactoperoxidase in Human Milk with Use of Immunoadsorbents with Antibodies against Recombinant Human Lactoperoxidase. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2001, 73, 984–989. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boots, J.W.; Floris, R. Lactoperoxidase: From Catalytic Mechanism to Practical Applications. Int. Dairy J. 2006, 16, 1272–1276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seifu, E.; Buys, E.M.; Donkin, E.F. Significance of the Lactoperoxidase System in the Dairy Industry and Its Potential Applications: A Review. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2005, 16, 137–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, F.K.; Santos, L.O.; Buffon, J.G. Mechanism of Action, Sources, and Application of Peroxidases. Food Res. Int. 2021, 143, 110266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harris, Z.L. Ceruloplasmin. Chapter 9. In Clinical and Translational Perspectives on Wilson Disease; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2019; pp. 77–84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helman, S.L.; Zhou, J.; Fuqua, B.K.; Lu, Y.; Collins, J.F.; Chen, H.; Vulpe, C.D.; Anderson, G.J.; Frazer, D.M. The biology of mammalian multi-copper ferroxidases. BioMetals 2022, 36, 263–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vashchenko, G.; MacGillivray, R.T.A. Multi-copper oxidases and human iron metabolism. Nutrients 2013, 5, 2289–2313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moshkov, K.A.; Zajcev, V.N.; Romanovskaja, E.V.; Stefanov, V.E. Ceruloplasmin: Intramolecular electron transfer and ferroxidase activity. Fundam. Res. 2014, 3-1, 104–108. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=21291815 (accessed on 30 September 2025). (In Russian).

- Puchkova, L.V.; Babich, P.S.; Zatulovskaia, Y.A.; Ilyechova, E.Y.; Di Sole, F. Copper metabolism of new borns is adapted to milk ceruloplasmin as a nutritive source of copper: Overview of the current data. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczubial, M.; Dabrowski, R.; Kankofer, M.; Bochniarz, M.; Komar, M. Concentration of serum amyloid A and ceruloplasmin activity in milk from cows with subclinical mastitis caused by different pathogens. Pol. J. Vet. Sci. 2012, 15, 291–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voronina, O.A.; Bogolyubova, N.V.; Zaitsev, S.Y. Mineral composition of cow milk—A mini review. Agric. Biol. 2022, 57, 681–693. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsymbalenko, N.V.; Gyulikhandanova, N.E.; Platonova, N.A.; Babich, V.S.; Evsyukova, I.I.; Puchkova, L.V. Regulation of ceruloplasmin gene activity in mammary gland cells. Russ. J. Genet. 2009, 45, 390–400. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=11713826 (accessed on 8 October 2025). (In Russian). [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.A.; Staufenbiel, R. Variations in copper concentration and ceruloplasmin activity of dairy cows in relation to lactation stages with regard to ceruloplasmin to copper ratios. Biol. Trace Elem. Res. 2012, 146, 47–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szczubial, M.; Dabrowski, R.; Kankofer, M.; Bochniarz, M.; Albera, E. Concentration of serum amyloid A and activity of ceruloplasmin in milk from cows with clinical and subclinical mastitis. Bull. Vet. Inst. Puławy 2008, 3, 391–395. [Google Scholar]

- Saleh, N.; Allam, T.S.; Omran, A.; Abdelfattah, A.M. Evaluation of Changes in Hemato-Biochemical, Inflammatory, and Oxidative Stress Indices as Reliable Diagnostic Biomarkers for Subclinical Mastitis in Cows. Alex. J. Vet. Sci. 2022, 72, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadat, A.; Farag, A.M.; Elhanafi, D.; Awad, A.; Elmahallawy, E.K.; Alsowayeh, N.; Elkhadragy, M.F.; Elshopakey, G.E. Immunological and Oxidative Biomarkers in Bovine Serum from Healthy, Clinical, and Sub-Clinical Mastitis Caused by Escherichia coli and Staphylococcus aureus Infection. Animals 2023, 13, 892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zykov, A.A.; Golovnev, B.A.; Zykova, A.A.; Belkina, O.M. Correlation of functionally active proteins in serum and central lymph during early crush syndrome. Health Care Kyrg. 2012, 2, 36–38. Available online: https://www.elibrary.ru/item.asp?id=30682570 (accessed on 8 October 2025). (In Kyrgyzstan).

- Voronina, O.A.; Zaitsev, S.Y.; Savina, A.A.; Kolesnik, N.S. Evaluation of the content of ceruloplasmin, copper and coppercoordinating amino acids in cow milk at different lactation periods. Agric. Sci. Euro-North-East 2023, 24, 1038–1048. (In Russian) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thaha, A.; Wang, B.-S.; Chang, Y.-W.; Hsia, S.-M.; Huang, T.-C.; Shiau, C.-Y.; Hwang, D.-F.; Chen, T.-Y. Food-Derived Bioactive Peptides with Antioxidative Capacity, Xanthine Oxidase and Tyrosinase Inhibitory Activity. Processes 2021, 9, 747. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, H. The milk fat globule membrane—A biophysical system for food applications. Curr. Opin. Colloid Interface Sci. 2006, 11, 154–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kathriarachchi, K.; Leus, M.; Everett, D.W. Oxidation of aldehydes by xanthine oxidase located on the surface of emulsions and washed milk fat globules. Int. Dairy J. 2014, 37, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Battelli, M.G.; Polito, L.; Bolognesi, A. Xanthine oxidoreductase in atherosclerosis pathogenesis: Not only oxidative stress. Atherosclerosis 2014, 237, 562–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khanna, D.; Fitzgerald, J.D.; Khanna, P.P.; Bae, S.; Singh, M.K.; Neogi, T.; Pillinger, M.H.; Merill, J.; Lee, S.; Prakash, S. American College of Rheumatology guidelines for management of gout. Part 1: Systematic nonpharmacologic and pharmacologic therapeutic approaches to hyperuricemia. Arthritis Rheum 2012, 64, 1431–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Tang, Y.; Liu, C.; Li, J.; Guo, L.; Zhang, Y. Development of a method to screen and isolate potential xanthine oxidase inhibitors from Panax japlcus var via ultrafiltration liquid chromatography combined with counter-current chromatography. Talanta 2015, 134, 665–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fass, D. The Erv family of sulfhydryl oxidases. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2008, 1783, 557–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Alon, A.; Heckler, E.J.; Thorpe, C.; Fass, D. QSOX contains a pseudo-dimer of functional and degenerate sulfhydryl oxidase domains. FEBS Lett. 2010, 584, 1521–1525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faccio, G.; Nivala, O.; Kruus, K.; Buchert, J.; Saloheimo, M. Sulfhydryl oxidases: Sources, properties, production and applications. Appl. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2011, 91, 957–966. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Janolino, V.G.; Swaisgood, H.E. A comparison of sulfhydryl oxidase from bovine milk and Aspergillus niger. Milchwissenschaft 1992, 47, 143–146. [Google Scholar]

- Jaje, J.; Wolcott, H.N.; Fadugba, O.; Cripps, D.; Yang, A.J.; Mather, I.H.; Thorpe, C. A flavin-dependent sulfhydryl oxidase in bovine milk. Biochemistry 2007, 46, 13031–13040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Hajfathalian, M.; Ghelichi, S.; Moreno, P.J.G.; Sørensen, A.-D.M.; Jacobsen, C. Peptides: Production, bioactivity, functionality, and applications. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2017, 58, 3097–3129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, S.A.; Emire, S.A. Production and processing of antioxidant bioactive peptides: A driving force for the functional food market. Heliyon 2020, 6, e04765. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minkiewicz, P.; Iwaniak, A.; Darewicz, M. BIOPEP-UWM Database of Bioactive Peptides: Current Opportunities. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 5978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sgarbieri, V.C. Impact of Bovine Milk Whey Proteins and Peptides on Gastrointestinal, Immune, and Other Systems. In Dairy in Human Health and Disease Across the Lifespan; Ronald Ross, W., Robert, J.C., Victor, R.P., Eds.; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2017; Chapter 3; pp. 31–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhar, H.; Verma, S.; Dogra, S.; Katoch, S.; Vij, R.; Singh, G.; Sharma, M. Functional attributes of bioactive peptides of bovine milk origin and application of in silico approaches for peptide prediction and functional annotations. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2023, 64, 9432–9454. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kashung, P.; Karuthapandian, D. Milk-derived bioactive peptides. Food Prod Process Nutr. 2025, 7, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suetsuna, K.; Ukeda, H.; Ochi, H. Isolation and characterization of free radical scavenging activities peptides derived from casein. J. Nutr. Biochem. 2000, 11, 128–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rival, S.G.; Boeriu, C.G.; Wichers, H.J. Caseins and casein hydrolysates. 2. Antioxidative properties Peroral calcium dosage of infants. Acta Med. Scand. 2001, 55, 247–255. [Google Scholar]

- Mohanty, D.P.; Mohapatra, S.; Misra, S.; Sahu, P.S. Milk derived bioactive peptides and their impact on human health—A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2016, 23, 577–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tonolo, F.; Folda, A.; Cesaro, L.; Scalcon, V.; Marin, O.; Ferro, S.; Bindoli, A.; Rigobello, M.P. Milk-derived bioactive peptides exhibit antioxidant activity through the Keap1-Nrf2 signaling pathway. J. Funct. Foods 2020, 64, 103696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krasnovsky, A.A. Primary mechanisms of photoactivation of molecular oxygen. History of development and current state of research. Biochemistry 2007, 72, 1311–1331. [Google Scholar]

- Kulinsky, V.I. Reactive oxygen species and oxidative modification of macromolecules: Benefit, harm, and protection. SOZH 1999, 1, 2–7. [Google Scholar]

- Kulinsky, V.I.; Kolesnichenko, L.S. Glutathione system 1. Synthesis, transport of glutathione transferase, glutathione peroxidase. Biomed. Chem. 2009, 55, 255–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mazo, V.K. Glutathione as a component of the antioxidant system of the gastrointestinal tract. Russ. J. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. Proctol. 1998, 8, 47–53. [Google Scholar]

- Doosh, K.S. Study the effect of purified cow milk glutathione on cancer cell growth (HePG2) in vitro. Int. J. Health Sci. 2022, 6, 11583–11592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hrubiak, A.; Beyene, A.; Yavorskyi, Y.; Gotsiride, I.; Ostafiychuk, B. Structural features and electrochemical behavior of amino acid-based biocomposites. Renew. Energy 2025, 254, 123758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jara-Palacios, M.J.; Begines, E.; Heredia, F.J.; Escudero-Gilete, M.L.; Hernanz, D. Effectiveness of Cyclic Voltammetry in Evaluation of the Synergistic Effect of Phenolic and Amino Acids Compounds on Antioxidant Activity: Optimization of Electrochemical Parameters. Foods 2024, 13, 906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaitsev, S.Y. Dynamic surface tension measurements as general approach to the analysis of animal blood plasma and serum. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 2016, 235, 201–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enache, T.A.; Oliveira-Brett, A.M. Pathways of Electrochemical Oxidation of Indolic Compounds. Electroanalysis 2011, 23, 1337–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kononenko, S.; Temiraev, R.; Baeva, Z.; Gazdarov, A. The role of antioxidants in the realization of milk potential. Kombikorma 2011, 6, 104–105. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Q.; Feng, Y.; Gu, G.; Guo, Z. Synthesis of Novel Amino Lactose and Evaluation of Its Antioxidant Property. Starch Stärke 2018, 70, 1700293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chauhan, S.; Kumar, S.; Gautam, V.; Mehrotra, S.; Singh, A.; Deepak, D.; Chauhan, S. Comparative Evaluation of Milk Oligosaccharides Isolated and Fractionated from Indigenous Rathi Cow Milk for Anti-Oxidant and Anti-Adhesive Properties. In Proceedings of the 3-rd International Electronic Conference on Processes—Green and Sustainable Process Engineering and Process Systems Engineering. Proceedings 2024, 105, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butler, G.; Nielsen, J.H.; Slots, T.; Seal, C.; Eyre, M.D.; Sanderson, R.; Leifert, C. Fatty acid and fat-soluble antioxidant concentrations in milk from high- and low-input conventional and organic systems: Seasonal variation. J. Sci. Food. Agric. 2008, 88, 1431–1441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shivaani, G. Comparative Analysis of Antioxidant Activity of Milk Phospholipids from Different Milk Formulations. J. Med. Care Health Rev. 2025, 2, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, I.T.; Nadeem, M.; Imran, M.; Ayaz, M.; Ajmal, M.; Ellahi, M.Y.; Khalique, A. Antioxidant capacity and fatty acids characterization of heat treated cow and buffalo milk. Lipids Health Dis. 2017, 16, 163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osawa, T.; Namiki, M. A novel type of antioxidant isolated from leaf wax of eucalyptus leaves. Agric. Biol. Chem. 1981, 45, 735–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, G.C.; Duh, P.D.; Tsai, C.L. Relationship between antioxidant activity and maturity of peanut hulls. J. Agric. Food Chem. 1993, 41, 67–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayemele, A.G.; Tilahun, M.; Lingling, S.; Elsaadawy, S.A.; Guo, Z.; Zhao, G.; Xu, J.; Bu, D. Oxidative Stress in Dairy Cows: Insights into the Mechanistic Mode of Actions and Mitigating Strategies. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1918. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trineeva, O.V. Methods for determining the antioxidant activity of objects of plant and synthetic origin in pharmacy (review). Dev. Regist. Med. 2017, 21, 180–197. [Google Scholar]

- Maksimova, T.V.; Nikulina, I.N.; Pakhomov, V.P.; Shkarina, E.I.; Chumakova, Z.V.; Arzamastsev, A.P. Method for Determining Antioxidant Activity. Russian Federation Patent No. 2170930; Moscow medical academy I.M. Sechenov: Moscow, Russia, 20 July 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Fomichev, Y.P.; Nikanova, L.A.; Dorozhkin, V.I.; Torshkov, A.A.; Romanenko, A.A.; Eskov, E.K.; Semenova, A.A.; Gonotsky, V.A.; Dunaev, A.V.; Yaroshevich, G.S.; et al. Dihydroquercetin and Arabinogalactan Are Natural Bioregulators in Human and Animal Life, Used in Agriculture and the Food Industry; Scientific Library: Moscow, Russia, 2017; 702p. [Google Scholar]

- Temerdashev, Z.A. Determination of the antioxidant activity of food products using the indicator system Fe(III)/Fe(II)—Organic reagent. Fact. Lab. Mater. Diagn. 2006, 72, 15–19. [Google Scholar]

- Benzie, I.F.; Strain, J.J. The ferric reducing ability of plasma (FRAP) as a measure of “antioxidant power”: The FRAP assay. Anal. Biochem. 1996, 239, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tsyupko, T.G.; Chuprynina, D.A.; Nikolaeva, N.A.; Voronova, O.B.; Temerdashev, Z.A. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of food products using an indicator system based on iron phenanthrolinate complexes. Izv. vuzov. Food Technol. 2011, 84–87. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/otsenka-antioksidantnoy-aktivnosti-pischevyh-produktov-s-ispolzovaniem-indikatornoy-sistemy-na-osnove-fenantrolinatnyh-kompleksov (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical Methods Used in Determining Antioxidant Activity: A Review. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferreira, R.; Avaca, L.A. Electrochemical Determination of the Antioxidant Capacity: The Ceric Reducing/Antioxidant Capacity (CRAC) Assay. Electroanalysis 2008, 20, 1323–1329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyürek, M.; Güçlü, K.; Tütem, E.; Sözgen Başkan, K.; Erçağ, E.; Karademir Çelik, S.; Baki, S.; Yıldız, L.; Karaman, Ş.; Apak, R. A comprehensive review of CUPRAC methodology. Anal. Methods 2011, 3, 2439–2453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gulcin, İ.; Alwasel, S.H. DPPH Radical Scavenging Assay. Processes 2023, 11, 2248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhtar, M.J.; Mondor, M.; Aïder, M. Impact of the drying mode and ageing time on sugar profiles and antioxidant capacity of electro-activated sweet whey. Int. Dairy J. 2018, 80, 17–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cano, A.; Maestre, A.B.; Hernández-Ruiz, J.; Arnao, M.B. ABTS/TAC Methodology: Main Milestones and Recent Applications. Processes 2023, 11, 185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balakireva, Y.V. Galvanostatic Coulometry for Assessing the Antioxidant Activity of Milk and Dairy Products; Publishing House “RANS”: Moscow, Russia, 2009; 60p. [Google Scholar]

- Abdullina, S.G.; Agapova, N.M.; Khaziev, R.S.; Ziyatdinova, G.K.; Budnikov, G.K. The Method of Coulometric Determination of the Content of Tannins in Vegetable Raw Materials. Patent RF No. 2436084, 6 April 2010. (BI. 2010. No. 4. pp. 13–15). [Google Scholar]

- Ziyatdinova, G.K.; Budnikov, G.K.; Pogoreltsev, V.I. Determination of serum albumin in blood by galvanostatic coulometry. J. Anal. Chem. 2004, 59, 742–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdullin, I.F.; Turova, E.N.; Budnikov, G.K. Coulometric evaluation of the antioxidant capacity of tea extracts by electrogenerated bromine. Anal. Chem. 2001, 56, 627–629. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Gorton, L.; Akersson, B. Electrochemical studies on antioxidants in bovine milk. Anal. Chim. Acta 2002, 474, 137–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chevion, S.; Roberts, M.A.; Chevion, M. The use of cyclic voltammetry for the evaluation of antioxidant capacity. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 860–870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kohen, R.; Vellaichamy, E.; Hrbac, J.; Gaty, I.; Tirosh, O. Quantification of the overall reactive oxygen species scavenging capacity of biological fluids and tissues. Free. Radic. Biol. Med. 2000, 28, 871–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korotkova, E.I.; Karbainov, Y.A.; Avramchik, O.A. Investigation of antioxidant and catalytic properties of some biological-active substances by voltammetry. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2003, 375, 465–468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Voronina, O.A.; Dovzhenko, N.A.; Milaeva, I.V.; Tsarkova, M.S. Comprehensive analysis of the colloid biochemical properties of animal milk as complex multicomponent system. BioNanoScience 2017, 7, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mora-Garrido, A.B.; Jara-Palacios, M.J.; Escudero-Gilete, M.L.; Cejudo-Bastante, M.J. Using Chemical Composition and Antioxidant Activity in Evaluation of Enological By-Products According to Type, Vinification Style, Season, and Grape Variety. Foods 2025, 14, 2405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fysun, O.; Khorshid, S.; Rauschnabel, J.; Langowski, H.-C. Detection of dairy fouling by cyclic voltammetry and square wave voltammetry. Food Sci. Nutr. 2020, 8, 3070–3080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motshakeri, M.; Phillips, A.R.J.; Kilmartin, P.A. Application of cyclic voltammetry to analyse uric acid and reducing agents in commercial milks. Food Chem. 2019, 293, 23–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brainina, H.Z.; Ivanova, A.V.; Sharafutdinova, E.N. Evaluation of the antioxidant activity of food products by potentiometry. Food Technol. 2004, 4, 73–75. [Google Scholar]

- Naumova, N.L. A modern view on the problem of studying the antioxidant activity of food products. Bull. South Ural. State University. Ser. Food Biotechnol. 2014, 2, 5–7. [Google Scholar]

- Khasanov, V.V.; Ryzhova, G.L.; Maltseva, E.V. Methods for the study of antioxidants. Chem. Plant Raw Mater. 2004, 63–75. Available online: https://cyberleninka.ru/article/n/metody-issledovaniya-antioksidantov/viewer (accessed on 8 October 2025).

- Ivanova, A.V.; Gerasimova, E.L.; Kravets, I.A.; Matern, A.I. Potentiometric determination of water-soluble antioxidants using metal complexes. J. Anal. Chem. 2015, 70, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savina, A.A.; Zaitsev, S.Y. Changes in the amount of water-soluble antioxidants in the milk of cows milked in the morning and evening. Vet. Anim. Sci. Biotechnol. (Vet. Zootekhniya I Biotekhnologiya) 2024, 9, 116–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y. Features of the Amino Acid Composition of Gelatins from Organs and Tissues of Farm Animals (A Review). Russ J. Bioorg. Chem. 2024, 50, 1966–1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaitsev, S.Y.; Savina, A.A.; Bogolyubova, N.V. Changes in the total amount of antioxidants in the milk of single milk cows at the peak of lactation. Agrar. Sci. 2022, 45–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| № | BAS *, Groups, Classes | Specific Compound | Molecular Mass (MM), Type of Reaction | Parameters and Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Enzymes, class oxidoreductases | Xanthine oxido- reductase, EC 1.17.3.2. | MM ~270 kDa; catalyzes the oxidation of hypoxanthine to xanthine and then to uric acid | Protein is a dimeric complex “molybdenum-flavo-enzyme”, a component of the membranes of fat globules |

| 2 | Enzymes, class oxidoreductases | Lactoperoxidase as NADH-peroxidase, EC 1.11.1.X | It is believed that the antimicrobial ability of lactoperoxidase is synergistic with lactoferrin and lysozyme | Iron-containing glycoprotein; the catalytic center contains protoporphyrin IX, covalently linked (S-S-bridge) to the polypeptide chain. Other examples: bromide (Br) → hypobromite (BrO) iodide (I) → hypoiodite (IO) |

| 3 | Enzymes, class oxidoreductases | Superoxide dismutase (SOD), EC 1.15.1.1 | MM ~32.5 kDa; catalyzes the dismutation of superoxide (superoxide radical) into oxygen and hydrogen peroxide. SOD has a high catalytic reaction rate (~109 M−1 s−1). | The superoxide dismutation reaction under the action of SOD: (1) M(n + 1)+ − COД + O2− → Mn+ − COД + O2 (2) Mn+ − COД + O2− + 2H+ → M(n + 1)+ − COД + H2O2., where M can be (Cu (n = 1); Mn (n = 2); Fe (n = 2); Ni (n = 2). |

| 4 | Enzymes, class oxidoreductases | Catalyse, EC 1.11.1.6 | MM ~250 kDa; catalyzes oxidation-reduction reaction: 2H2O2→2H2O + O2. | In a reaction, two molecules of hydrogen peroxide form water and oxygen |

| 5 | Peptides, tripeptides | Glutathione or γ-glutamylcysteinylglycine | MM~307 Da, C10H17N3O6S, tripeptide or (2-amino-5-{[2-[(carboxymethyl)amino]-1-(mercaptomethyl)-2-oxoethyl]amino}-5-oxopentanoic acid | Glutathione in its reduced form can function as an antioxidant in several ways: by chemically interacting with singlet oxygen, superoxide, and hydroxyl radicals or by directly destroying free radicals, and by stabilizing membrane structure |

| 6 | Amino acids, SH-containing compounds | Cysteine, methionine | CYS *, MM 121.16 Da, C3H7NO2S, MET *, MM 149.21 Da C5H11NO2S | Cysteine and methionine are among the most powerful antioxidants; their antioxidant effect is enhanced in the presence of vitamin C and selenium |

| 7 | Lipids, monounsaturated fatty acids (MUFAs) | Oleic acid, palmitoleic acid | MM 282,46 Da C18H34O2 C17H33COOH MM 256.5 Da C16H32O2 C15H31COOH | MUFAs react with bases, oxidizing agents, reducing agents, and also with oxygen to form lipid peroxidation products (LPO) |

| 8 | Lipids, polyunsaturated fatty acids (PUFAs) | Linoleic acid linolenic acid arachidonic acid | MM 280.45 Da C18H32O2 MM 278,43 Da C18H30O2 MM 304.47 Da C20H32O2 | PUFA react with bases, oxidizing agents, reducing agents, and also with oxygen to form lipid peroxidation products (LPO) |

| 9 | Vitamins, fat-soluble vitamins | Vitamins A, E, K | α-tocopherol MM 430.7 Da; β-tocopherol MM 416.7 Da; γ-tocopherol MM 416.7 Da; δ-tocopherol MM 402.7 Da | Some of the most powerful antioxidants; they are light yellow oils soluble in acetone, EtOH, CHCl3, and diethyl ether and insoluble in H2O |

| 10 | Vitamins, water-soluble vitamins | Vitamin C, vitamin B6, vitamin PP | MM 176.12 Da C6H8O6. MM 169.18 Da C8H11NO3 MM 123.11 Da C6H5NO2 | Some of the most powerful antioxidants |

| 11 | Low-molecular-weight antioxidants, phenols, poly-phenols | Tocopherol acetate, eugenol, pyrocatechin, gallic acid | MM 472.8 (430.7) Da C31H52O3. MM 164.20 Da C10H12O2 MM 110.11 Da C6H6O2 MM 170.12 Da C7H6O5 | α-tocopherol acetate (light yellow oil), λmax 292 nm, ε 3260, eugenol, pyrocatechol, and gallic acid are bioactive compounds; they are derivatives of phenolic acid and have strong antioxidant properties |

| Amino Acid | TP1 g/100 g | TP2 mg/100 g | TP3 g/100 g | TP4 mg/kg | AOA a.u. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ASP | 0.23–0.26 | 219 | 0.232 | 0.7–2.9 | - |

| THR | 0.11–0.12 | 153 | 0.145 | 0.8–1.4 | - |

| SER | 0.17–0.19 | 186 | 0.175 | 0.8–2.8 | - |

| GLU | 0.59–0.67 | 509 | 0.651 | 4.0–32.0 | - |

| GLY | 0.04–0.05 | 47 | --- | 2.0–15.0 | - |

| ALA | 0.12–0.14 | 98 | 0.100 | 1.4–2.9 | - |

| VAL | 0.20–0.23 | 191 | 0.199 | 0.6–1.5 | - |

| ILE | 0.16–0.19 | 189 | 0.180 | 0.3–0.9 | - |

| LEU | 0.30–0.35 | 283 | 0.326 | 0.2–0.9 | - |

| TYR | 0.14–0.17 | 184 | 0.154 | 0.1–0.5 | ++ |

| PHE | 0.15–0.18 | 175 | 0.167 | 0.1–0.3 | + |

| HIS | 0.08–0.10 | 90 | 0.097 | 0.7–5.5 | - |

| LYS | 0.26–0.30 | 261 | 0.273 | 2.8–8.1 | - |

| ARG | 0.12–0.14 | 122 | 0.121 | 1.4–4.5 | - |

| PRO | 0.21–0.25 | 278 | 0.327 | 2.5–5.4 | - |

| TRP | --- | 50 | 0.048 | --- | +++ |

| MET | 0.12–0.14 | 83 | 0.113 | 0.3–0.7 | + |

| CYS | 0.03–0.04 | 27 | 0.028 | 0.1–5.8 | + |

| № | Method and Reaction Type | Substances or Indicators | Medium and Reagent | Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | “Ox–Red” titration | Major WSA *, including quercetin (in mg/g) | 0.05 N potassium permanganate solution (in ml), aqueous medium | 1. “Visual fixation of the equivalence point” [229,230] 2. “Photometric titration according to Levetal with optical detection” [231] |

| 2 | «FRAP» spectroscopy | Ascorbic acid, glutathione and cysteine | Fe(III)/Fe(II) | Assessment by the intensity of color of the complex Fe(II)-pyridyl-2,6-dicarboxylic acid, Fe(II)-ferrocene [232,233,234,235] |

| 3 | «CUPRAC» spectroscopy | Ascorbic acid, glutathione and cysteine | Ce(II) (λ = 450 nm) | Assessment by the intensity of color of the Cu2+ complex (λ = 450 nm) [233,235] (2011). A comprehensive review of CUPRAC methodology: Analytical Methods. 3. 2439–2453. 10.1039/C1AY05320E. |

| 4 | «CRAC» spectroscopy | Ascorbic acid, glutathione and cysteine | Ce(IV) (λ = 320 nm) | «CRAC» “oxidation–reduction reaction” [233,236] |

| 5 | DPPH spectroscopy | Major WSA * | 1,1-diphenyl-2-picryl-hydrazyl hydrate (λ = 517–519 nm) | DPPH radical scavenging assay [237,238] |

| 6 | ABTS spectroscopy | Major WSA * | 2,2-Azino-bis(3-ethylbenzothiazoline-6-sulfonic acid) (λ = 320 nm) | ABTS/TAC methodology [238,239] |

| 7 | Coulometry or coulometric titration | Major WSA * | 0.1 M potassium iodide solution in phosphate buffer solution (pH = 9.8) on a platinum electrode | Electrogenerated titrants are hypoiodite ions formed by disproportionation of electrogenerated iodine in an alkaline medium [240,241,242,243] |

| 8 | Voltammetry or «cyclic voltammetry» | Major WSA * | Process of electro-reduction (ER) of oxygen on a mercury film electrode | Process of electro-reduction (ER) of oxygen on a mercury film electrode [244,245,246,247,248,249] |

| 9 | Potentiometric method | Major WSA * | K3[Fe(CN)6]/K4[Fe(CN)6] system nMeOxL + AO = nMeRedL + AOOx | гдe MeOxL—“oxidized form of metal and ligand”; MeRedL—reduced form of metal and ligand; AO—antioxidant being determined; AOOx—the oxidation product of this antioxidant [250,251,252,253] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Zaitsev, S.Y. Major Antioxidants and Methods for Studying Their Total Activity in Milk: A Review. Methods Protoc. 2025, 8, 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060139

Zaitsev SY. Major Antioxidants and Methods for Studying Their Total Activity in Milk: A Review. Methods and Protocols. 2025; 8(6):139. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060139

Chicago/Turabian StyleZaitsev, Sergei Yu. 2025. "Major Antioxidants and Methods for Studying Their Total Activity in Milk: A Review" Methods and Protocols 8, no. 6: 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060139

APA StyleZaitsev, S. Y. (2025). Major Antioxidants and Methods for Studying Their Total Activity in Milk: A Review. Methods and Protocols, 8(6), 139. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps8060139