Community Mobilization and Community Incentivization (CoMIC) Strategy for Child Health in a Rural Setting of Pakistan: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial

Abstract

1. Background

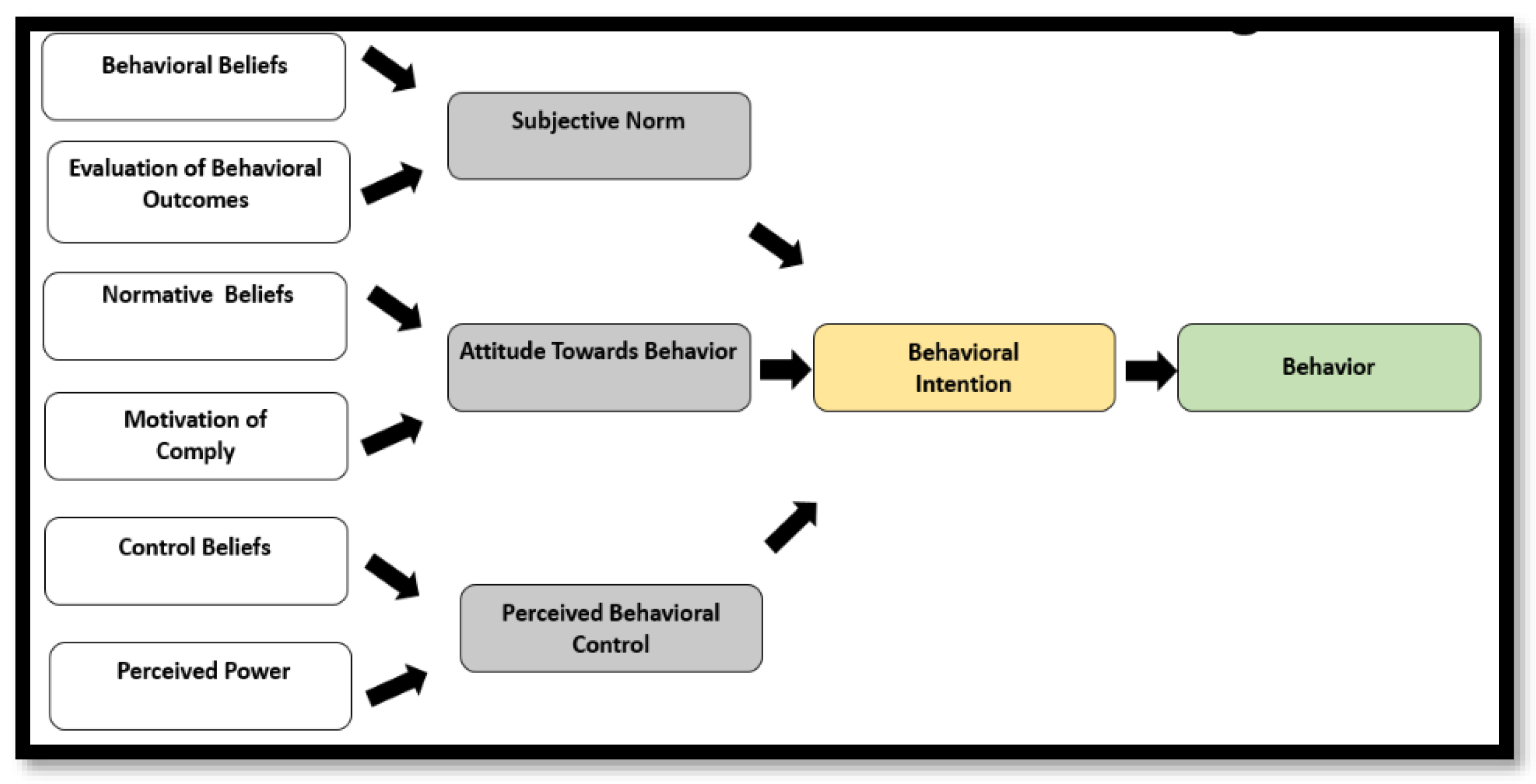

2. Conceptual Framework

- Theory of planned behavior—is useful in getting information on what details people need before attempting a behavior change.

- Subjective norms—these relate to a person’s belief about what others think that he or she should do.

- Attitudes towards behavior—these are determined by a belief that desired outcomes will occur if a particular behavior is followed.

- Perceived behavior control—recognizes that a behavior change is likely if a person has greater personal control over behavior (self-efficacy).

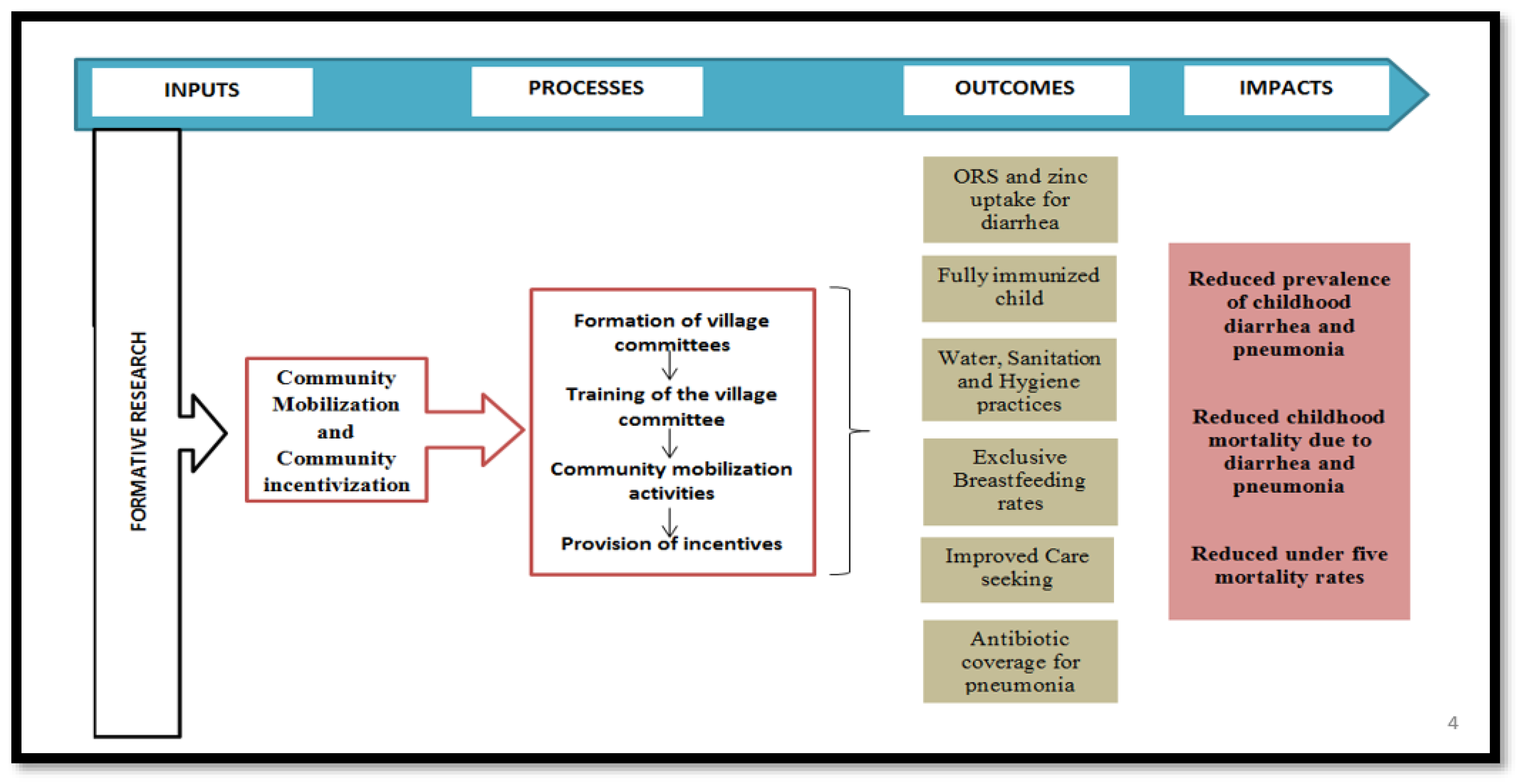

3. Methodology

3.1. Objective

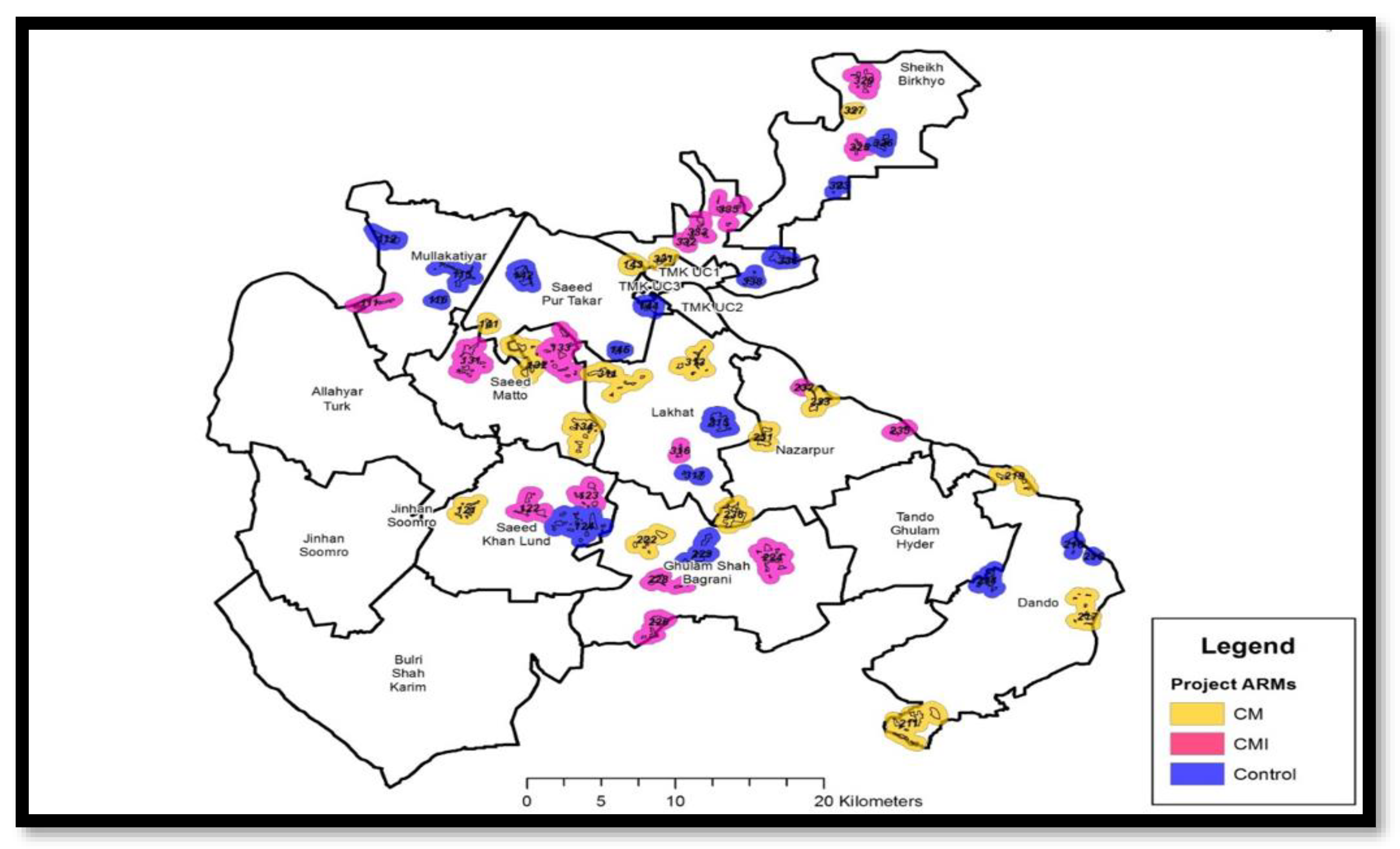

3.2. Study Setting

3.3. Study Design

3.4. Study Population

3.5. Study Duration and Registration

3.6. Outcomes

- Fully immunized child (FIC)—defined as vaccination determined by the age of the child and the vaccines received up to 23 months of age.

- ORS use—defined as children who used ORS for the last episode of diarrhea.

- Sanitation index (SI)—The SI was adopted from Webb et al. [32] and comprised four indices with a total of 15 items. These four indicators included the drinking water index (DWI), food index (FI), personal hygiene index (PHI), and domestic household hygiene index (DHI) (Table 1). Each item was scored as 0 or 1, with 1 representing a positive behavior. The indices were calculated as the sum of the items and SI was calculated as the sum of the four individual indices. For our study, we excluded PHI, as it would be difficult to assess with intermittent surveys, and the potential absence of subjects at home at the time of the survey. In our study, the SI comprised three indices with 12 items, hence a total score of 12.

- EBF: EBF was defined as no other food or drink except breast milk (including milk expressed or from a wet nurse) taken for 6 months of life, but allowing the infant to receive ORS, drops, and syrups (vitamins, minerals, and medicines) [33].

- Prevalence of diarrhea: Diarrhea was defined as the passage of three or more loose or liquid stools per day (or more frequent passage than is normal for the individual) within two weeks of the day of survey [34].

- Prevalence of ARI: ARI was defined as children under 5 years of age, who have cough and/or difficulty breathing, with or without fever within two weeks of the day of survey [35].

- Care seeking for childhood diarrhea and ARI: Healthcare-seeking behavior was defined as professional help sought from health-care services, health-care providers and/or community health workers for childhood illnesses.

- Open defecation rates.

3.7. Formative Phase

- Assess the geographic spread and density of the population and the location of key landmarks.

- Assess the socio-demographic status and the major tribes within each village.

- Assess the existing health and hygiene-related practices and behaviors.

- Identify the enablers and barriers associated with the existing care-seeking practices, and uptake of evidence-based interventions for childhood diarrhea and pneumonia.

- Identify community preferences pertaining to the community mobilization activities and the development of Information, Education and Communication (IEC) material.

- Design the potential conditional community-based non-cash incentives that could be beneficial for the community.

3.8. Sample Size Calculation

3.9. Randomization

4. Intervention

4.1. Intervention Arm 1: Community Mobilization (CM)

4.1.1. Training

4.1.2. Information, Education and Communication (IEC) Materials

- Posters.

- Pictorial brochures/flip charts.

- Short promotional videos in the local language (Sindhi) (58).

4.1.3. Activities

- VC meetings (Triggering sessions).

- Meetings supervised by research staff (Participatory Learning).

- Sessions with children in schools/community (Change Leaders).

- Every month for the first six months.

- Every two months for the second six months.

- Quarterly in the second year of the study.

- Educational sessions with key WASH and health-related massages.

- Display of IEC material inside school areas and classrooms.

- Involving schoolteachers to check personal hygiene—clothes, nails, shoes, and hair.

- School (playground, classroom, water containers) cleaning activities.

- Competitions and games related to hygiene and nutrition including posters competition, singing, etc.

- Gifts for the best student.

4.1.4. Compliance

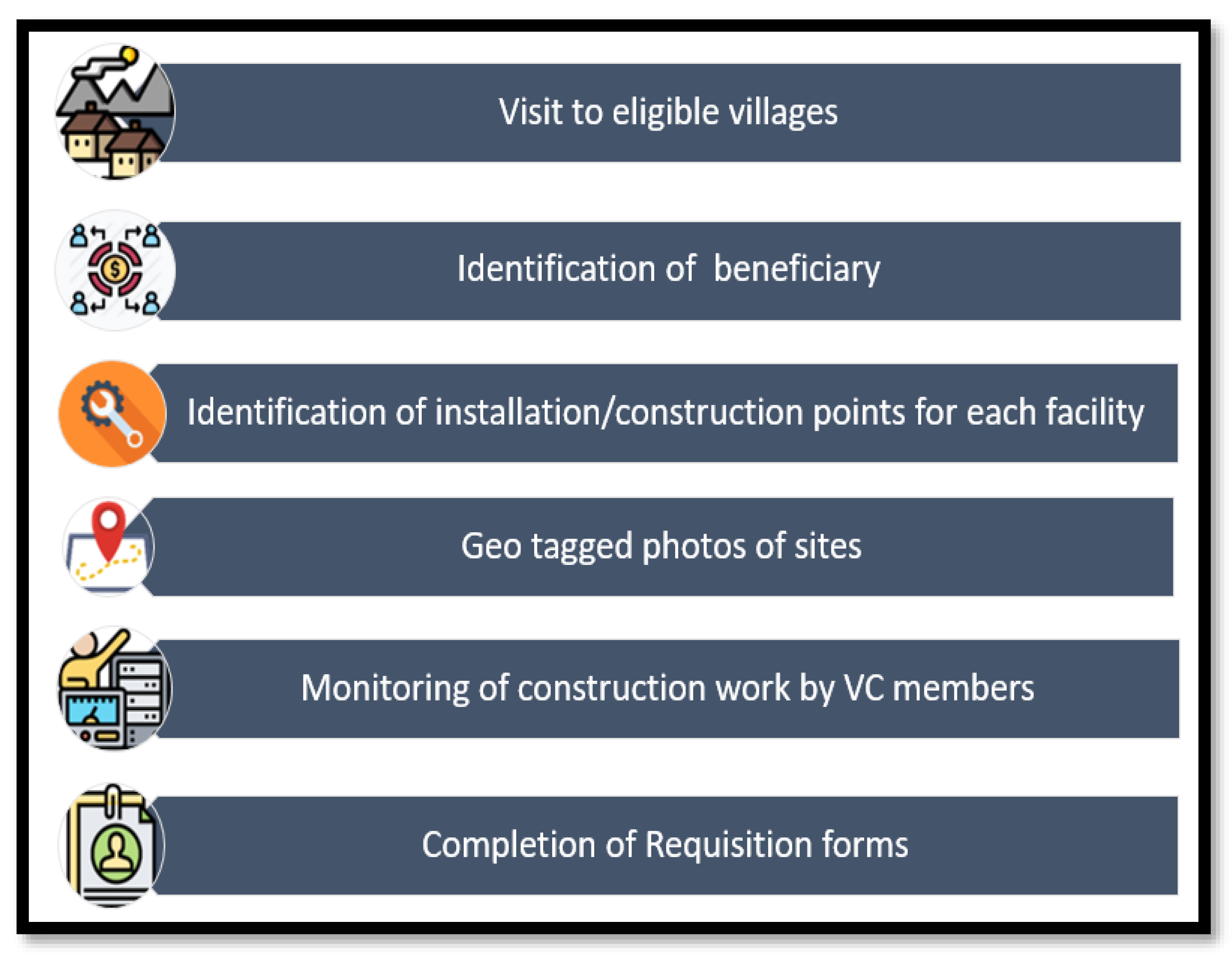

4.2. Intervention Arm 2: Community Mobilization and Incentivization (CMI)

- FIC (age-appropriate).

- ORS use for diarrhea.

- Sanitation index (which is a score based on DWI, FI, and DHI).

- At 6 months—10% improvement in the composite coverage from baseline (min. 5% each).

- At 15 months—25% improvement in the composite coverage from baseline (min. 15% each).

- At 24 months—50% improvement in the composite coverage from baseline (min. 30% each).

- Drinking water facilities (including simple handpumps, lead line handpumps, lead line water facilities with solar motor pumps).

- Sanitation facilities–latrine/washing facility (complete structure), latrine/washing facility (only sub-structure), repair of the drainage system.

4.3. Control Arm: Standard Care

5. Data Collection

5.1. Components of Data Collection

5.2. Training

5.3. Pilot Testing

5.4. Quality Assurance

5.5. Statistical Analysis

6. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- UNIGME. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2021, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation; United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UNIGME) and United Nations Children’s Fund: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- UNIGME. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2020, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation; United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UN IGME): New York, NY, USA, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfeld, S.; O’Connor, E.; Sung, V.; Roberts, G.; Wake, M.; West, S.; Hiscock, H. Potential indirect impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on children: A narrative review using a community child health lens. Med. J. Aust. 2022, 216, 364–372. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, G.R. Tackling pneumonia and diarrhoea: The deadliest diseases for the world’s poorest children. Lancet 2012, 379, 2123–2124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Greenslade, L. Securing the Future of the Integrated Global Action Plan for Pneumonia and Diarrhoea (GAPPD); WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Aboubaker, S. The Integrated Global Action Plan for the Prevention and Control of Pneumonia and Diarrhoea; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, B.X.; Kjaerulf, F.; Turner, S.; Cohen, L.; Donnelly, P.D.; Muggah, R.; Davis, R.; Realini, A.; Kieselbach, B.; MacGregor, L.S.; et al. Transforming our world: Implementing the 2030 agenda through sustainable development goal indicators. J. Public Health Policy 2016, 37, 13–31. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, L.; Oza, S.; Hogan, D.; Perin, J.; Rudan, I.; Lawn, J.E.; Cousens, S.; Mathers, C.; Black, R.E. Global, regional, and national causes of child mortality in 2000–2013, with projections to inform post-2015 priorities: An updated systematic analysis. Lancet 2015, 385, 430–440. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rizvi, A.; Bhatti, Z.; Das, J.K.; Bhutta, Z.A. Pakistan and the millennium development goals for maternal and child health: Progress and the way forward. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2015, 35, 287–297. [Google Scholar]

- Bhutta, Z.A.; Das, J.K.; Walker, N.; Rizvi, A.; Campbell, H.; Rudan, I.; Black, R.E. Interventions to address deaths from childhood pneumonia and diarrhoea equitably: What works and at what cost? Lancet 2013, 381, 1417–1429. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- UNIGME. Levels & Trends in Child Mortality: Report 2019, Estimates Developed by the United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation; United Nations Children’s Fund, United Nations Inter-Agency Group for Child Mortality Estimation (UNIGME): New York, NY, USA, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- IVAC. Pneumonia and Diarrhea Progress Report 2018; Driving Progress through Equitable Investment and Action; International Vaccine Access Center (IVAC) at Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health: Baltimore, MD, USA, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Becker, M.H.; Haefner, D.P.; Kasl, S.V.; Kirscht, J.P.; Maiman, L.A.; Rosenstock, I.M. Selected psychosocial models and correlates of individual health-related behaviors. Med. Care 1977, 15, 27–46. [Google Scholar]

- Gittelsohn, J.; Steckler, A.; Johnson, C.C.; Pratt, C.; Grieser, M.; Pickrel, J.; Stone, E.J.; Conway, T.; Coombs, D.; Staten, L.K. Formative research in school and community-based health programs and studies: “State of the art” and the TAAG approach. Health Educ. Behav. 2006, 33, 25–39. [Google Scholar]

- Bassani, D.G.; Arora, P.; Wazny, K.; Gaffey, M.F.; Lenters, L.; Bhutta, Z.A. Financial incentives and coverage of child health interventions: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, S30. [Google Scholar]

- Chopra, M.; Sharkey, A.; Dalmiya, N.; Anthony, D.; Binkin, N. Strategies to improve health coverage and narrow the equity gap in child survival, health, and nutrition. Lancet 2012, 380, 1331–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Cooper, J.E.; Benmarhnia, T.; Koski, A.; King, N.B. Cash transfer programs have differential effects on health: A review of the literature from low and middle-income countries. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 247, 112806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peabody, J.W.; Shimkhada, R.; Quimbo, S.; Solon, O.; Javier, X.; McCulloch, C. The impact of performance incentives on child health outcomes: Results from a cluster randomized controlled trial in the Philippines. Health Policy Plan. 2014, 29, 615–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertler, P. Do conditional cash transfers improve child health? Evidence from PROGRESA’s control randomized experiment. Am. Econ. Rev. 2004, 94, 336–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basinga, P.; Gertler, P.J.; Binagwaho, A.; Soucat, A.L.; Sturdy, J.; Vermeersch, C.M. Effect on maternal and child health services in Rwanda of payment to primary health-care providers for performance: An impact evaluation. Lancet 2011, 377, 1421–1428. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernald, L.C.; Gertler, P.J.; Neufeld, L.M. Role of cash in conditional cash transfer programmes for child health, growth, and development: An analysis of Mexico’s Oportunidades. Lancet 2008, 371, 828–837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watson, J.A.; Ensink, J.H.J.; Ramos, M.; Benelli, P.; Holdsworth, E.; Dreibelbis, R.; Cumming, O. Does targeting children with hygiene promotion messages work? The effect of handwashing promotion targeted at children, on diarrhoea, soil-transmitted helminth infections and behaviour change, in low- and middle-income countries. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2017, 22, 526–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Laverack, G. The Challenge of Behaviour Change and Health Promotion. Challenges 2017, 8, 25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sallis, J.F.; Owen, N.; Fisher, E.B. Ecological models of health behavior. Health Behav. Health Educ. Theory Res. Pract. 2008, 4, 465–486. [Google Scholar]

- Conner, M.; Norman, P. Health Behavior Models; Tobacco Control Resource Center: Halethorpe, MD, USA, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Olney, D.K.; Gelli, A.; Kumar, N.; Alderman, H.; Go, A.; Raza, A.; Owens, J.; Grinspun, A.; Bhalla, G.; Benammour, O. Nutrition-Sensitive Social Protection Programs within Food Systems; Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations International Food Policy Research Institute: Washington, DC, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Stokols, D. Translating social ecological theory into guidelines for community health promotion. Am. J. Health Promot. 1996, 10, 282–298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeroy, K.R.; Bibeau, D.; Steckler, A.; Glanz, K. An ecological perspective on health promotion programs. Health Educ. Behav. 1988, 15, 351–377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simplican, S.C.; Leader, G.; Kosciulek, J.; Leahy, M. Defining social inclusion of people with intellectual and developmental disabilities: An ecological model of social networks and community participation. Res. Dev. Disabil. 2015, 38, 18–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hochbaum, G.; Rosenstock, I.; Kegels, S. Health Belief Model; United States Public Health Service: North Bethesda, MD, USA, 1952; p. 1.

- Das, J.K. Community Mobilization and Incentivization for Childhood Diarrhea and Pneumonia (CoMIC): Clinicaltrials.gov. 2018. Available online: https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT03594279 (accessed on 23 December 2022).

- Habib, M.A.; Soofi, S.; Sadiq, K.; Samejo, T.; Hussain, M.; Mirani, M.; Rehmatullah, A.; Ahmed, I.; Bhutta, Z.A. A study to evaluate the acceptability, feasibility and impact of packaged interventions (“Diarrhea Pack”) for prevention and treatment of childhood diarrhea in rural Pakistan. BMC Public Health 2013, 13, 922. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Exclusive Reastfeeding. Available online: http://www.who.int/elena/titles/exclusive_breastfeeding/en/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Diarrheal Diseases. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs330/en/ (accessed on 9 November 2022).

- The World Health Organisation (WHO). Pneumonia. Available online: http://www.who.int/mediacentre/factsheets/fs331/en/ (accessed on 18 November 2022).

- Donald, S.G.; Lang, K. Inference with Difference-in-Differences and Other Panel Data. Rev. Econ. Stat. 2007, 89, 221–233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- StataCorp. Stata Statistical Software: Release 17; StataCorp LLC: College Station, TX, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Arimond, M.; Ruel, M.T. Assessing Care: Progress Towards the Measurement of Selected Childcare and Feeding Practices, and Implications for Programs; Food and Nutrition Technical Assistance Project, Academy for Educational Development: Washington, DC, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar]

| Indices | Items |

|---|---|

| Drinking water index (DWI) | Interior water container water is covered |

| Exterior water container is clean | |

| Container contains water | |

| Food index (FI) | Clean dishes are covered |

| Clean dishes are stored high | |

| All food is covered | |

| Personal hygiene index (PHI) | Mother/caregiver is wearing shoes |

| Mother’s/caregiver’s hands are clean | |

| Index child’s hands are clean | |

| Domestic household hygiene index (DHI) | No trash in yard |

| No trash inside home | |

| No unrestrained animals | |

| No dirty clothes accumulated in the home | |

| Insignificant quantity of flies inside the home | |

| No standing water on the home patio |

| Challenges | Solutions |

|---|---|

| Vaccination | |

|

|

| ORS | |

|

|

| Hygiene | |

|

|

| Breastfeeding | |

|

|

| Sections Included in the Data Collection Tool |

|---|

| Section A: Geo-Spatial location coordinates |

| section B: Household identification and demographic information |

| Section C: Introduction and consent |

| Section D: Household members’ information |

| Section E: Socio-economic status of household |

| Section F: Reproductive health, maternal health |

| Section G: Child health (diarrhea) |

| Section H: Child health (acute respiratory infection (ARI)) |

| Section I: Immunization |

| Section J: Breastfeeding and nutrition |

| Section K: Water and sanitation |

| Section L: Handwashing |

| Section M: Sanitation index (spot check) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2023 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Das, J.K.; Salam, R.A.; Rizvi, A.; Soofi, S.B.; Bhutta, Z.A. Community Mobilization and Community Incentivization (CoMIC) Strategy for Child Health in a Rural Setting of Pakistan: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Methods Protoc. 2023, 6, 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps6020030

Das JK, Salam RA, Rizvi A, Soofi SB, Bhutta ZA. Community Mobilization and Community Incentivization (CoMIC) Strategy for Child Health in a Rural Setting of Pakistan: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Methods and Protocols. 2023; 6(2):30. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps6020030

Chicago/Turabian StyleDas, Jai K., Rehana A. Salam, Arjumand Rizvi, Sajid B. Soofi, and Zulfiqar A. Bhutta. 2023. "Community Mobilization and Community Incentivization (CoMIC) Strategy for Child Health in a Rural Setting of Pakistan: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial" Methods and Protocols 6, no. 2: 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps6020030

APA StyleDas, J. K., Salam, R. A., Rizvi, A., Soofi, S. B., & Bhutta, Z. A. (2023). Community Mobilization and Community Incentivization (CoMIC) Strategy for Child Health in a Rural Setting of Pakistan: Study Protocol for a Randomized Controlled Trial. Methods and Protocols, 6(2), 30. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps6020030