Healthcare Service Interventions to Improve the Healthcare Outcomes of Hospitalised Patients with Extreme Obesity: Protocol for an Evidence and Gap Map

Abstract

:1. Background

1.1. Introduction

The Problem, Condition, or Issue

1.2. The Intervention

Why Is It Important to Develop the EGM

2. Objectives

- Identify available systematic reviews, primary studies, and impact and outcome-based evaluations of healthcare service interventions for hospitalised patients with extreme obesity.

- Provide database entries of included studies that summarise the intervention, context, study design, and main results.

- Identify gaps in the evidence where further primary research is needed.

- Identify gaps in the evidence related to healthcare equity.

3. Methodology

3.1. Evidence and Gap Maps: Definition and Purpose

- Develop an intervention/outcome framework

- Identify the current evidence

- Critically appraise the quality of the evidence

- Extract, code, and summarise the data in relation to the EGM objectives

- Visualise and present our findings

3.2. Framework Development, and Scope

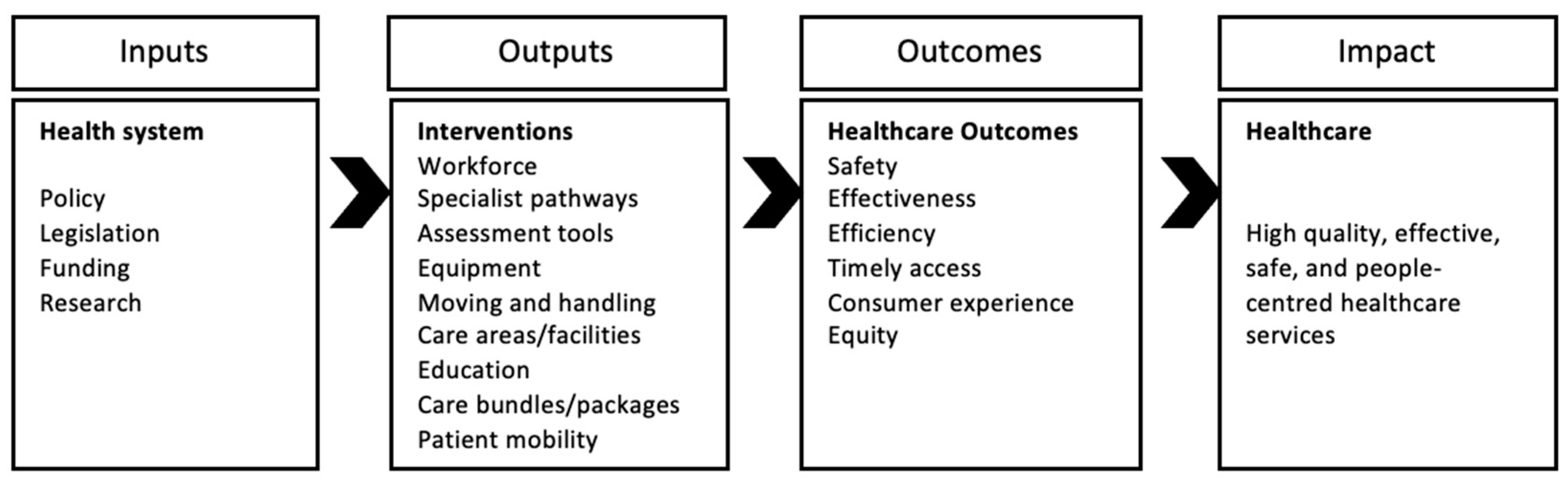

3.3. Conceptual Framework

3.4. Eligibility Criteria

3.5. Dimensions

3.5.1. Types of Study Design

3.5.2. Types of Settings

3.5.3. Status of Studies

3.5.4. Population

3.5.5. Interventions

3.5.6. Outcomes

3.6. Search Methods and Sources

3.7. Screening and Selection of Studies

3.8. Data Extraction, Coding and Management

3.9. Quality Appraisal

4. Analysis and Presentation

4.1. Report Structure

- Tables and figures we will include:

- Figure: Conceptual framework.

- Figure: PRISMA flowchart.

- Table: Number of studies by study design.

- Table: Number of studies by interventions and outcomes.

- Table: Number of studies that considered health equity and indigeneity.

- Other tables and figures will be included based on coded information for selected filters.

- Appendix: Full search strategy used for each database.

4.1.1. Dependency

4.1.2. The Evidence Gap Map

5. Stakeholder Engagement

- Dr. Junior Ulu, Director Pacific Peoples Health 2 DHB, Capital & Coast and Hutt Valley District Health Boards.

- Dr. Aliitasi Su’a Tavila, Senior Lecturer in Pasifika Health, School of Health, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

- Levi Vaoga, Healthcare consumer, New Zealand.

- Tuppy Parker, Whānau Care Services, Capital and Coast District Health Board, New Zealand.

- Miriam Coffey, Mental Health and Additions Service, Hutt Valley District Health Board, New Zealand.

- Te Manu Tūtaki, Mental Health and Additions Service, Hutt Valley District Health Board, New Zealand.

- Catherine Gerrard, Programme Manager, System Improvement, Ministry of Health, New Zealand.

- Eleanor Barrett, Occupational Therapist, Moving & Handling Advisor, Capital and Coast District Health Board, New Zealand.

- Dr. Maureen Coombs, Adjunct Professor, School of Nursing Midwifery and Health Practice, Victoria University of Wellington, New Zealand.

- Ina Farrelly, Podiatrist, Registered Nurse, Health Consultant, Board of Trustee-Tissue Viability Society, United Kingdom.

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Category | Terms |

|---|---|

| Population | 1 exp Obesity/(231744) |

| 2 exp Obesity, Morbid/(22668) | |

| 3 exp Bariatrics/(29463) | |

| 4 Bariatric*.ti,ab. (18305) | |

| 5 Morbid* Obes*.ti,ab. (13372) | |

| 6 Extrem* Obes*.ti,ab. (1341) | |

| 7 High BMI.ti,ab. (3372) | |

| 8 High Body Mass Index.ti,ab. (2522) | |

| 9 or/1–8 (247341) | |

| Setting | 10 exp Hospitals/(291947) |

| 11 exp Inpatients/(25076) | |

| 12 Acute Care.ti,ab. (20974) | |

| 13 Acute Setting.ti,ab. (1916) | |

| 14 ward.ti,ab. (36072) | |

| 15 hospital.ti,ab. (927103) | |

| 16 inpatient.ti,ab. (76402) | |

| 17 In-patient.ti,ab. (58968) | |

| 18 or/10–17 (1188901) | |

| Outcomes | 19 exp Nurse Specialists/(18972) |

| 20 exp Nurse Practitioners/(18407) | |

| 21 exp Specialization/(25010) | |

| 22 exp Patient Care Team/(71013) | |

| 23 exp Occupational Therapists/(442) | |

| 24 exp Physicians/(155870) | |

| 25 Bariatric Nurse*.ti,ab. (5) | |

| 26 Clinical Nurse Specialist*.ti,ab. (2434) | |

| 27 Clinical Nurse Educator*.ti,ab. (88) | |

| 28 Nurse Practitioner*.ti,ab. (11324) | |

| 29 Specialist.ti,ab. (52728) | |

| 30 Pharmacist.ti,ab. (13905) | |

| 31 “Moving and Handling”.ti,ab. (83) | |

| 32 “Health and Safety”.ti,ab. (8691) | |

| 33 or/19–32 (343954) | |

| 34 exp Managed Care Programs/(40100) | |

| 35 exp Patient Care Planning/(65846) | |

| 36 exp Policy/(165284) | |

| 37 exp Public Policy/(146609) | |

| 38 exp Health Policy/(111165) | |

| 39 exp Practice Guideline/(28281) | |

| 40 exp “Quality of Health Care”/(7464622) | |

| 41 exp Quality Assurance, Health Care/(342838) | |

| 42 exp Quality Indicators, Health Care/(23340) | |

| 43 exp Quality Control/(50654) | |

| 44 exp Clinical Protocols/(178336) | |

| 45 Care Pathway.ti,ab. (2425) | |

| 46 Care plan.ti,ab. (4220) | |

| 47 pathway.ti,ab. (658329) | |

| 48 policy.ti,ab. (174273) | |

| 49 guideline.ti,ab. (52647) | |

| 50 standard.ti,ab. (802981) | |

| 51 quality standard.ti,ab. (1739) | |

| 52 protocol.ti,ab. (294069) | |

| 53 treatment plan.ti,ab. (11830) | |

| 54 toolkit.ti,ab. (5813) | |

| 55 process planning.ti,ab. (73) | |

| 56 or/34–55 (8894186) | |

| 57 exp Needs Assessment/(31744) | |

| 58 exp Risk Assessment/(292110) | |

| 59 exp Nursing Assessment/(32875) | |

| 60 exp Symptom Assessment/(6416) | |

| 61 exp Accidental Falls/(26370) | |

| 62 exp Pressure Ulcer/(12900) | |

| 63 exp Skin Care/(6669) | |

| 64 exp Skin/(233916) | |

| 65 exp Nutrition Assessment/(16280) | |

| 66 exp Anthropometry/(536972) | |

| 67 exp Body Weight/(490539) | |

| 68 exp Body Size/(520583) | |

| 69 Assessment.ti,ab. (904374) | |

| 70 Assessment tool.ti,ab. (15266) | |

| 71 assessment framework.ti,ab. (903) | |

| 72 “admission to discharge planning”.ti,ab. (10) | |

| 73 fall*.ti,ab. (192589) | |

| 74 mobility.ti,ab. (122346) | |

| 75 mobility index.ti,ab. (483) | |

| 76 DEMMI.ti,ab. (54) | |

| 77 “Timed up and go”.ti,ab. (4354) | |

| 78 TUG.ti,ab. (2819) | |

| 79 Pressure Injuries.ti,ab. (642) | |

| 80 skin.ti,ab. (497819) | |

| 81 risk assessment.ti,ab. (58205) | |

| 82 nutrition.ti,ab. (146196) | |

| 83 anthropometric.ti,ab. (41243) | |

| 84 body size.ti,ab. (18966) | |

| 85 or/57–84 (2847824) | |

| 86 exp “Equipment and Supplies”/(1548572) | |

| 87 exp Beds/(4495) | |

| 88 exp Toilet Facilities/(1776) | |

| 89 exp Bathroom Equipment/(131) | |

| 90 exp Hygiene/(43565) | |

| 91 exp Baths/(5394) | |

| 92 exp Friction/(4178) | |

| 93 exp Surgical Equipment/(275737) | |

| 94 exp Airway Management/(123907) | |

| 95 Equipment.ti,ab. (79127) | |

| 96 Bed*.ti,ab. (150753) | |

| 97 chair*.ti,ab. (19542) | |

| 98 commode*.ti,ab. (117) | |

| 99 toileting.ti,ab. (924) | |

| 100 hygiene.ti,ab. (50654) | |

| 101 gown*.ti,ab. (1252) | |

| 102 shower trolley*.ti,ab. (5) | |

| 103 handrail*.ti,ab. (260) | |

| 104 Mattress*.ti,ab. (3617) | |

| 105 Pressure relieving mattresses.ti,ab. (17) | |

| 106 table*.ti,ab. (116457) | |

| 107 mobility aid*.ti,ab. (326) | |

| 108 hoist*.ti,ab. (234) | |

| 109 sling*.ti,ab. (6855) | |

| 110 friction reduction device*.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 111 sliding sheet*.ti,ab. (14) | |

| 112 hover jack*.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 113 hover mat*.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 114 surgical.ti,ab. (897279) | |

| 115 airway*.ti,ab. (153820) | |

| 116 or/86–115 (2888742) | |

| 117 exp “Moving and Lifting Patients”/(673) | |

| 118 exp Lifting/(2729) | |

| 119 “Moving and handling”.ti,ab. (83) | |

| 120 patient transfer.ti,ab. (829) | |

| 121 manual handling.ti,ab. (655) | |

| 122 patient mobilisation.ti,ab. (43) | |

| 123 or/119–122 (1590) | |

| 124 exp Policy/(165284) | |

| 125 exp Risk Assessment/(292110) | |

| 126 exp Inservice Training/(29753) | |

| 127 policy.ti,ab. (174273) | |

| 128 program*.ti,ab. (809323) | |

| 129 risk assessment.ti,ab. (58205) | |

| 130 transfer technique*.ti,ab. (1903) | |

| 131 technique*.ti,ab. (1331789) | |

| 132 training.ti,ab. (376304) | |

| 133 equipment.ti,ab. (79127) | |

| 134 hoist*.ti,ab. (234) | |

| 135 sling*.ti,ab. (6855) | |

| 136 transfer aid.ti,ab. (6) | |

| 137 skill*.ti,ab. (183599) | |

| 138 competenc*.ti,ab. (79640) | |

| 139 mobilisation.ti,ab. (5488) | |

| 140 lifting.ti,ab. (9814) | |

| 141 twin turner.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 142 yoke.ti,ab. (211) | |

| 143 or/124–142 (3092636) | |

| 144 123 and 143 (726) | |

| 145 ward*.ti,ab. (56038) | |

| 146 bariatric ward.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 147 bedspace*.ti,ab. (18) | |

| 148 zone*.ti,ab. (170648) | |

| 149 theatre*.ti,ab. (8233) | |

| 150 area.ti,ab. (828973) | |

| 151 structure*.ti,ab. (1466510) | |

| 152 facilities.ti,ab. (93604) | |

| 153 or/145–152 (2497826) | |

| 154 exp Education/(850563) | |

| 155 exp Inservice Training/(29753) | |

| 156 exp Teaching/(89719) | |

| 157 exp Teaching Materials/(121626) | |

| 158 exp Learning/(407031) | |

| 159 education.ti,ab. (416666) | |

| 160 training*.ti,ab. (377330) | |

| 161 in-service education.ti,ab. (442) | |

| 162 inservice education.ti,ab. (392) | |

| 163 competencies.ti,ab. (14547) | |

| 164 bariatric competencies.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 165 teaching.ti,ab. (128521) | |

| 166 study day.ti,ab. (1823) | |

| 167 program*.ti,ab. (809323) | |

| 168 instruction*.ti,ab. (58712) | |

| 169 learning.ti,ab. (268912) | |

| 170 or/154–169 (2453731) | |

| 171 exp Patient Care Bundles/(1053) | |

| 172 exp “Delivery of Health Care”/(1147360) | |

| 173 Bariatric Care Bundle.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 174 Care Bundle.ti,ab. (468) | |

| 175 Equipment Bundle.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 176 “Bundle* of Care”.ti,ab. (238) | |

| 177 Grouping.ti,ab. (18388) | |

| 178 Package.ti,ab. (36444) | |

| 179 Care Package.ti,ab. (339) | |

| 180 or/171–179 (1198340) | |

| 181 exp Mobility Limitation/(5046) | |

| 182 exp Posture/(76539) | |

| 183 exp Postural Balance/(25553) | |

| 184 exp Gait/(32260) | |

| 185 exp Muscle Strength/(38586) | |

| 186 Immobility.ti,ab. (9966) | |

| 187 mobilisation.ti,ab. (5488) | |

| 188 mobility.ti,ab. (122346) | |

| 189 mobility index.ti,ab. (483) | |

| 190 immobilisation.ti,ab. (3927) | |

| 191 patient mobility.ti,ab. (468) | |

| 192 early mobilisation.ti,ab. (775) | |

| 193 balance.ti,ab. (199259) | |

| 194 gait.ti,ab. (45997) | |

| 195 seating.ti,ab. (2193) | |

| 196 strength.ti,ab. (245959) | |

| 197 DEMMI.ti,ab. (54) | |

| 198 “Timed Up and GO”.ti,ab. (4354) | |

| 199 TUG.ti,ab. (2819) | |

| 200 Biomechanics.ti,ab. (15886) | |

| 201 Musculoskeletal.ti,ab. (46688) | |

| 202 movement.ti,ab. (211243) | |

| 203 structure.ti,ab. (957468) | |

| 204 posture.ti,ab. (26465) | |

| 205 transfer to sitting.ti,ab. (9) | |

| 206 transfer to standing.ti,ab. (12) | |

| 207 or/181–206 (1855003) | |

| 208 exp Mortality/(406552) | |

| 209 exp Death/(155086) | |

| 210 “28-day mortality”.ti,ab. (2363) | |

| 211 mortality.ti,ab. (722192) | |

| 212 mortality rate.ti,ab. (83423) | |

| 213 in hospital death.ti,ab. (3697) | |

| 214 in patient death.ti,ab. (93) | |

| 215 inhospital death.ti,ab. (108) | |

| 216 inpatient death.ti,ab. (249) | |

| 217 or/208–216 (1111368) | |

| 218 exp Patient Readmission/(20099) | |

| 219 readmission.ti,ab. (21335) | |

| 220 readmission rates.ti,ab. (5430) | |

| 221 hospital readmission.ti,ab. (3976) | |

| 222 or/218–221 (30239) | |

| 223 exp “Length of Stay”/(95705) | |

| 224 length of stay.ti,ab. (54865) | |

| 225 LOS.ti,ab. (43140) | |

| 226 length of hospital stay.ti,ab. (21550) | |

| 227 LOHS.ti,ab. (234) | |

| 228 hospital length of stay.ti,ab. (8647) | |

| 229 HLOS.ti,ab. (164) | |

| 230 Hospital Stay.ti,ab. (71888) | |

| 231 bed-night*.ti,ab. (24) | |

| 232 or/223–231 (194089) | |

| 233 exp Medical Errors/(117783) | |

| 234 exp Patient Safety/(23273) | |

| 235 exp “Wounds and Injuries”/(947923) | |

| 236 exp Cross Infection/(62185) | |

| 237 “Hospital acquired patient injur*”.ti,ab. (0) | |

| 238 nosocomial.ti,ab. (28313) | |

| 239 patient injur*.ti,ab. (750) | |

| 240 pressure injur*.ti,ab. (1063) | |

| 241 pressure sore*.ti,ab. (2806) | |

| 242 bed sore.ti,ab. (50) | |

| 243 hospital associated complication.ti,ab. (2) | |

| 244 near-misses.ti,ab. (883) | |

| 245 treatment injur*.ti,ab. (113) | |

| 246 or/233–245 (1152365) | |

| 247 exp Accidental Falls/(26370) | |

| 248 fall*.ti,ab. (192589) | |

| 249 slip*.ti,ab. (16348) | |

| 250 or/247–249 (214433) | |

| 251 exp Occupational Injuries/(3193) | |

| 252 Musculoskeletal Injury.ti,ab. (1119) | |

| 253 Staff Injur*.ti,ab. (129) | |

| 254 Staff.ti,ab. (143203) | |

| 255 Sprain.ti,ab. (2438) | |

| 256 Strain.ti,ab. (392600) | |

| 257 Back Injur*.ti,ab. (1325) | |

| 258 252 or 255 or 256 or 257 (397087) | |

| 259 254 and 258 (1140) | |

| 260 251 or 253 or 259 (4445) | |

| 261 exp Efficiency/(36286) | |

| 262 exp Efficiency, Organizational/(22202) | |

| 263 Efficiency.ti,ab. (360472) | |

| 264 timeliness.ti,ab. (4433) | |

| 265 readiness.ti,ab. (15315) | |

| 266 availability.ti,ab. (197682) | |

| 267 responsive.ti,ab. (130119) | |

| 268 or/261–267 (723857) | |

| 269 exp “Delivery of Health Care”/(1147360) | |

| 270 268 and 269 (48358) | |

| 271 exp Health Resources/(27986) | |

| 272 Resources Utilisation.ti,ab. (25) | |

| 273 Resource*.ti,ab. (308711) | |

| 274 Human Resource*.ti,ab. (9191) | |

| 275 Physical Resource*.ti,ab. (343) | |

| 276 272 or 273 or 274 or 275 (308711) | |

| 277 271 and 276 (11178) | |

| 278 exp Patient Satisfaction/(95120) | |

| 279 exp “Quality of Health Care”/(7464622) | |

| 280 exp Patient Satisfaction/(95120) | |

| 281 Patient Experience*.ti,ab. (15658) | |

| 282 Patient Satisfaction.ti,ab. (32831) | |

| 283 Decision Making.ti,ab. (124871) | |

| 284 Partnership.ti,ab. (21826) | |

| 285 Choice.ti,ab. (263534) | |

| 286 Quality of Care.ti,ab. (48508) | |

| 287 Experience.ti,ab. (619595) | |

| 288 Consumer Experience.ti,ab. (74) | |

| 289 Engagement.ti,ab. (60723) | |

| 290 Involvement.ti,ab. (426241) | |

| 291 Value.ti,ab. (873889) | |

| 292 Belief.ti,ab. (29936) | |

| 293 or/278–292 (8706734) | |

| 294 exp Patient-Centered Care/(22178) | |

| 295 exp Community Participation/(45303) | |

| 296 Person Centered.ti,ab. (2586) | |

| 297 Patient Centered.ti,ab. (14618) | |

| 298 People Centered.ti,ab. (104) | |

| 299 Decision-Making.ti,ab. (124871) | |

| 300 Individualised.ti,ab. (5634) | |

| 301 Personal Plan.ti,ab. (21) | |

| 302 296 or 297 or 298 (17209) | |

| 303 299 or 300 or 301 (130250) | |

| 304 302 and 303 (1731) | |

| 305 exp Social Discrimination/(9120) | |

| 306 exp Social Stigma/(10289) | |

| 307 exp Stereotyping/(11500) | |

| 308 exp Prejudice/(32932) | |

| 309 Harrassment.ti,ab. (11) | |

| 310 Neglect.ti,ab. (18003) | |

| 311 Stereotyping.ti,ab. (1318) | |

| 312 Marginalised.ti,ab. (994) | |

| 313 Marginalisation.ti,ab. (390) | |

| 314 Prejudice.ti,ab. (3995) | |

| 315 Bias.ti,ab. (149249) | |

| 316 Weight bias.ti,ab. (334) | |

| 317 discrimination.ti,ab. (107232) | |

| 318 stigma.ti,ab. (21581) | |

| 319 or/305–318 (388199) | |

| 320 exp Health Care Costs/(68905) | |

| 321 exp Health Expenditures/(23922) | |

| 322 exp “Fees and Charges”/(30886) | |

| 323 exp “Cost of Illness”/(29549) | |

| 324 exp “Costs and Cost Analysis”/(249475) | |

| 325 exp Cost-Benefit Analysis/(86407) | |

| 326 Economic.ti,ab. (196294) | |

| 327 Direct Cost*.ti,ab. (6720) | |

| 328 Indirect Cost*.ti,ab. (5524) | |

| 329 Cost*.ti,ab. (542860) | |

| 330 Cost of Illness.ti,ab. (1575) | |

| 331 Cost of Disease.ti,ab. (274) | |

| 332 Cost Consequence.ti,ab. (231) | |

| 333 Cost Effectiveness.ti,ab. (54501) | |

| 334 Money.ti,ab. (19165) | |

| 335 Economic Impact.ti,ab. (8605) | |

| 336 Economic Effect.ti,ab. (456) | |

| 337 Burden.ti,ab. (188886) | |

| 338 Consequence.ti,ab. (141269) | |

| 339 or/320–338 (1322986) | |

| 340 exp Health Equity/(2127) | |

| 341 exp Respect/(560) | |

| 342 exp Empathy/(20658) | |

| 343 Equity.ti,ab. (15028) | |

| 344 “Quality of Care”.ti,ab. (48508) | |

| 345 Quality.ti,ab. (929626) | |

| 346 Person-Centered.ti,ab. (2586) | |

| 347 Dignity.ti,ab. (6319) | |

| 348 Compassion.ti,ab. (5348) | |

| 349 Respect.ti,ab. (313373) | |

| 350 or/341–349 (1536596) | |

| 351 exp Health Services Accessibility/(118783) | |

| 352 exp Communication Barriers/(7083) | |

| 353 Access.ti,ab. (284767) | |

| 354 Access to Care.ti,ab. (11007) | |

| 355 Barrier* to care.ti,ab. (2735) | |

| 356 barrier*.ti,ab. (259819) | |

| 357 missed care.ti,ab. (194) | |

| 358 disparities.ti,ab. (43325) | |

| 359 geographical location.ti,ab. (3136) | |

| 360 region.ti,ab. (839785) | |

| 361 socio-economic.ti,ab. (29135) | |

| 362 cultural competency.ti,ab. (1184) | |

| 363 cultural safety.ti,ab. (343) | |

| 364 cultural.ti,ab. (91321) | |

| 365 or/351–364 (1852363) | |

| 366 exp Quality Improvement/(29965) | |

| 367 exp Program Evaluation/(79906) | |

| 368 Quality Initiative.ti,ab. (1807) | |

| 369 Quality Improv*.ti,ab. (34936) | |

| 370 QIP.ti,ab. (139) | |

| 371 Quality Improvement Project.ti,ab. (2829) | |

| 372 Program Evaluation*.ti,ab. (3772) | |

| 373 or/366–372 (141302) | |

| 374 exp Treatment Outcome/(1142196) | |

| 375 exp Health Impact Assessment/(810) | |

| 376 Effect.ti,ab. (3002769) | |

| 377 Outcome.ti,ab. (944031) | |

| 378 Impact.ti,ab. (905409) | |

| 379 Consequence.ti,ab. (141269) | |

| 380 Benefit.ti,ab. (354940) | |

| 381 Advantage.ti,ab. (152684) | |

| 382 Efficacy.ti,ab. (759530) | |

| 383 Success.ti,ab. (257404) | |

| 384 Result.ti,ab. (951017) | |

| 385 Quality.ti,ab. (929626) | |

| 386 or/374–385 (8488887) | |

| Study Design | 387 systematic review.pt. (166201) |

| 388 randomized controlled trial.pt. (544063) | |

| 389 randomised control* trial.ti,ab. (23281) | |

| 390 randomely.ti,ab. (11) | |

| 391 randomly.ti,ab. (311378) | |

| 392 Group*.ti,ab. (3449273) | |

| 393 Observational.ti,ab. (170413) | |

| 394 cohort study.ti,ab. (185196) | |

| 395 Case Controlled Study.ti,ab. (1913) | |

| 396 Surveys.ti,ab. (111451) | |

| 397 Cross Sectional Study.ti,ab. (146161) | |

| 398 Cross Sectional Studies.ti,ab. (9278) | |

| 399 Usual Care.ti,ab. (16398) | |

| 400 Qualitative.ti,ab. (210624) | |

| 401 or/387–400 (4418973) | |

| 402 (33 or 56 or 85 or 116 or 144 or 153 or 170 or 180 or 207 or 217 or 222 or 232 or 246 or 250 or 260 or 270 or 277 or 293 or 304 or 319 or 339 or 350 or 365 or 373 or 386) (18390064) (21018197) | |

| 403 (9 and 18 and 402 and 403) (6735) |

References

- Ministry of Health Clinical Guidelines for Weight Management in New Zealand Adults. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/clinical-guidelines-weight-management-new-zealand-adults (accessed on 24 July 2018).

- OECD The Heavy Burden of Obesity: The Economics of Prevention. 2019. Available online: https://www.oecd.org/health/the-heavy-burden-of-obesity-67450d67-en.htm (accessed on 31 August 2021).

- Ministry of Health Annual Update of Key Results 2019/2020: New Zealand Health Survey. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/annual-update-key-results-2019-20-new-zealand-health-survey (accessed on 25 March 2021).

- Ministry of Health Annual Data Explorer 2020/2021: New Zealand Health Survey. Available online: https://minhealthnz.shinyapps.io/nz-health-survey-2020-21-annual-data-explorer/_w_fd3f3f1c/#!/explore-indicators (accessed on 17 February 2022).

- Ministry of Health Understanding Excess Body Weight: New Zealand Health Survey. 2015. Available online: https://www.health.govt.nz/publication/understanding-excess-body-weight-new-zealand-health-survey (accessed on 10 September 2021).

- National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Classification of Overweight and Obesity by BMI, Waist Circumference, and Associated Disease Risks. Available online: https://www.nhlbi.nih.gov/health/educational/lose_wt/BMI/bmi_dis.htm (accessed on 31 March 2021).

- Caleyachetty, R.; Barber, T.M.; Mohammed, N.I.; Cappuccio, F.P.; Hardy, R.; Mathur, R.; Banerjee, A.; Gill, P. Ethnicity-Specific BMI Cutoffs for Obesity Based on Type 2 Diabetes Risk in England: A Population-Based Cohort Study. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2021, 9, 419–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hales, C.; de Vries, K.; Coombs, M. The Challenges in Caring for Morbidly Obese Patients in Intensive Care: A Focused Ethnographic Study. Aust. Crit. Care 2018, 31, 37–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Accident Compensation Corporation. Moving and Handling People: Bariatric Clients; Accident Compensation Corporation: Wellington, New Zealand, 2012; pp. 387–406. [Google Scholar]

- Hossain, M.A.; Amin, A.; Paul, A.; Qaisar, H.; Akula, M.; Amirpour, A.; Gor, S.; Giglio, S.; Cheng, J.; Mathew, R.; et al. Recognizing Obesity in Adult Hospitalized Patients: A Retrospective Cohort Study Assessing Rates of Documentation and Prevalence of Obesity. J. Clin. Med. 2018, 7, 203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Fusco, K.; Robertson, H.; Galindo, H.; Hakendorf, P.; Thompson, C. Clinical Outcomes for the Obese Hospital Inpatient: An Observational Study. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 2050312117700065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gallagher, S. A Practical Guide to Bariatric Safe Patient Handling and Mobility; Vision Publishing: Sarasota, FL, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hauck, K.; Hollingsworth, B. The Impact of Severe Obesity on Hospital Length of Stay. Med. Care 2010, 48, 335–340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ness, S.J.; Hickling, D.F.; Bell, J.J.; Collins, P.F. The Pressures of Obesity: The Relationship between Obesity, Malnutrition and Pressure Injuries in Hospital Inpatients. Clin. Nutr. 2017, 37, 1569–1574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hales, C. Misfits: An Ethnographic Study of Extremely Fat Patients in Intensive Care. Ph.D. Thesis, Victoria University, Wellington, New Zealand, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Hales, C.; Curran, N.; deVries, K. Morbidly Obese Patients’ Experiences of Mobility during Hospitalisation and Rehabilitation: A Qualitative Descriptive Study. Nurs. Prax. N. Z. 2018, 3, 20–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanderwolf, V. Does One Size Fit All? Factors Associated with Prolonged Length of Stay among Patients Who Have Bariatric Needs in a New Zealand Hospital: A Retrospective Chart Review. Master’s Thesis, University of Auckland, Auckland, New Zealand, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Grieve, E.; Fenwick, E.; Yang, H.-C.; Lean, M. The Disproportionate Economic Burden Associated with Severe and Complicated Obesity: A Systematic Review. Obes. Rev. 2013, 14, 883–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kent, S.; Fusco, F.; Gray, A.; Jebb, S.A.; Cairns, B.J.; Mihaylova, B. Body Mass Index and Healthcare Costs: A Systematic Literature Review of Individual Participant Data Studies. Obes. Rev. 2017, 18, 869–879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Withrow, D.; Alter, D.A. The Economic Burden of Obesity Worldwide: A Systematic Review of the Direct Costs of Obesity. Obes. Rev. 2011, 12, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wharton, S.; Lau, D.C.W.; Vallis, M.; Sharma, A.M.; Biertho, L.; Campbell-Scherer, D.; Adamo, K.; Alberga, A.; Bell, R.; Boulé, N.; et al. Obesity in Adults: A Clinical Practice Guideline. CMAJ 2020, 192, E875–E891. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization Guideline: Assessing and Managing Children at Primary Health-Care Facilities to Prevent Overweight and Obesity in the Context of the Double Burden of Malnutrition. 2017. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789241550123 (accessed on 29 September 2021).

- Snilstveit, B.; Vojtkova, M.; Bhavsar, A.; Gaarder, M. Evidence Gap Maps? A Tool for Promoting Evidence-Informed Policy and Prioritizing Future Research; Policy Research Working Papers; The World Bank: Washington, DC, USA, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Health Quality & Safety Commission the Triple Aim. Available online: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/news-and-events/ (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Quality of Care. Available online: https://www.who.int/westernpacific/health-topics/quality-of-care (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- Australian Commission on Safety and Quality in Health Care The State of Patient Safety and Quality in Australian Hospitals. 2019. Available online: https://www.safetyandquality.gov.au/publications-and-resources/resource-library/state-patient-safety-and-quality-australian-hospitals-2019 (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- Health Quality & Safety Commission Dashboard of Health System Quality. Available online: https://www.hqsc.govt.nz/our-programmes/health-quality-evaluation/projects/quality-dashboards/dashboard-of-health-system-quality/ (accessed on 11 October 2021).

- National Health Service National Quality Board Position Statement on Quality in Integrated Care Systems. 2021. Available online: https://www.england.nhs.uk/publication/national-quality-board-position-statement-on-quality-in-integrated-care-systems/ (accessed on 11 November 2021).

- World Health Organization Quality Health Services: A Planning Guide. 2020. Available online: https://www.who.int/publications-detail-redirect/9789240011632 (accessed on 27 September 2021).

- Snilstveit, B.; Vojtkova, M.; Bhavsar, A.; Stevenson, J.; Gaarder, M. Evidence & Gap Maps: A Tool for Promoting Evidence Informed Policy and Strategic Research Agendas. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2016, 79, 120–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- White, H.; Albers, B.; Gaarder, M.; Kornør, H.; Littell, J.; Marshall, Z.; Matthew, C.; Pigott, T.; Snilstveit, B.; Waddington, H.; et al. Guidance for Producing a Campbell Evidence and Gap Map. Campbell Syst. Rev. 2020, 16, e1125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- EPPI-Centre Home. Available online: https://eppi.ioe.ac.uk/cms/ (accessed on 13 September 2021).

- Braithwaite, J.; Hibbert, P.; Blakely, B.; Plumb, J.; Hannaford, N.; Long, J.C.; Marks, D. Health System Frameworks and Performance Indicators in Eight Countries: A Comparative International Analysis. SAGE Open Med. 2017, 5, 2050312116686516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Carini, E.; Gabutti, I.; Frisicale, E.M.; Di Pilla, A.; Pezzullo, A.M.; de Waure, C.; Cicchetti, A.; Boccia, S.; Specchia, M.L. Assessing Hospital Performance Indicators. What Dimensions? Evidence from an Umbrella Review. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2020, 20, 1038. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Institute of Medicine; Committee on Quality of Health Care in America; National Academy of Sciences. Crossing the Quality Chasm: A New Health System for the 21st Century; National Academies Press: Washington, DC, USA, 2001; ISBN 978-0-309-51193-3. [Google Scholar]

- Lazar, E.J.; Fleischut, P.; Regan, B.K. Quality Measurement in Healthcare. Annu. Rev. Med. 2013, 64, 485–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubin, H.R.; Pronovost, P.; Diette, G.B. The Advantages and Disadvantages of Process-based Measures of Health Care Quality. Int. J. Qual. Health Care 2001, 13, 469–474. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shea, B.J.; Reeves, B.C.; Wells, G.; Thuku, M.; Hamel, C.; Moran, J.; Moher, D.; Tugwell, P.; Welch, V.; Kristjansson, E.; et al. AMSTAR 2: A Critical Appraisal Tool for Systematic Reviews That Include Randomised or Non-Randomised Studies of Healthcare Interventions, or Both. BMJ 2017, 358, j4008. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

| Intervention | Definition |

|---|---|

| Specialist workforce | Designated health professional roles/positions employed specifically to manage/care for hospitalised patients with extreme obesity. Examples: MeSH Term—“Nurse Specialist” = ‘Nursing professionals whose practice is limited to a particular area or discipline of medicine’ (MEDLINE, Ovid). “Patient Care Team”—‘Care of patients by a multidisciplinary team usually organised under the leadership of a physician’ |

| Special care pathways | Processes that guide the care of hospitalised patients with extreme obesity. Examples: MeSH Term—“Patient Care Planning” = ‘a written medical and nursing care program designed for a particular patient’ (MEDLINE, Ovid) |

| Assessment tools | Assessment tools used to assess patient risk and guide care during hospital admission. Examples: MeSH Term—“Needs Assessment” = systematic identification of a population’s needs or the assessment of individuals to determine the proper level of services needed (MEDLINE, Ovid) |

| Equipment | Specialist equipment used/needed in the care of hospitalised patients with extreme obesity. Examples: MeSH Term = “Equipment and Supplies” = Expendable and nonexpendable equipment, supplies, apparatus, and instruments that are used in diagnostic, surgical, therapeutic, scientific, and experimental procedures.’ (MEDLINE, Ovid). |

| Moving and handling | Processes used during care for the movement and transfer of patients with extreme obesity. The lifting, transferring, repositioning, or mobilising of part or all of a patient’s body. (Focus of the research is on processes to support staff to enable patient mobilisation.) Examples: MeSH Term—“Moving and Lifting Patients” = ‘Moving or repositioning patients within their beds, from bed to bed, bed to chair, or otherwise from one posture or surface to another.’ |

| Specialist care areas | Specific areas/wards where the physical environment has been designed for caring for patients with extreme obesity. Examples: Ward OR Bedspace OR Facilities (Search as keywords in MEDLINE, Ovid) |

| Education | Bariatric specific education/training designed to improve care delivery for patients with extreme obesity by healthcare professionals. Examples: MeSH Term “Inservice Training”—on the job training programs for personnel carried out within an institution or agency’ (MEDLINE, Ovid) |

| Care bundles/packages | Groupings of care interventions/practices that, when implemented collectively, improve the reliability of their delivery, and improve patient and healthcare outcomes. Examples: MeSH Term “Patient Care Bundles” = ‘small sets of evidence-based interventions for a defined patient population and care setting’ (MEDLINE, Ovid). |

| Patient mobility | Patient mobility during their hospital admission. (Focus of the research is on improving the biomechanics of patient mobility.) Examples: MeSH Term “Mobility Limitation”—‘difficulty walking from place to place’ (MEDLINE, Ovid). OR ‘Immobility’, ‘patient mobility’, ‘transfer to sitting’, or ‘transfer to standing’ searched as keywords. |

| Outcome Measures | Subcategory | Definition |

|---|---|---|

| Safety | Patient injury | Any hospital-acquired patient injury, adverse event, and care practice that caused harm to the patient. |

| Patient falls | Any fall occurring during hospitalisation/hospital stay. | |

| Staff injury | Any injury or condition experienced during the delivery of care to patients with extreme obesity. | |

| Effectiveness | Providing services based on scientific knowledge to all those who could benefit and refraining from those who would likely not benefit. Outcome data represents either the size of the problem or the reduction in harm.

| |

| Efficiency | Costs | Direct costs of healthcare provision for hospitalised patients with extreme obesity. Costs accrued during an inpatient care episode. |

| Resource utilisation | Maximizing the benefit of available resources and avoiding waste.

| |

| Timely access | Timeliness of healthcare system’s capacity to provide care quickly after a need is recognised. Reducing waiting times and harmful delays.

| |

| Patient experience | Satisfaction/experience | The overall patient assessment of the quality of care received during their hospital stay using measures like: being treated with kindness and respect, being listened to, and being involved in decisions. |

| Person-centred | Providing care that responds to individual preferences, needs, and values. | |

| Discrimination | The unjust or prejudicial treatment of the patient with extreme obesity because of their physical health condition or appearance. | |

| Health equity | Quality of care | Providing care that does not vary in quality on account of the patient having extreme obesity.

|

| Access to care | Access to appropriate care based on identified needs of the patient with extreme obesity.

| |

| Quality improvement | Improvement efforts aim to improve outcomes for patients with extreme obesity. |

| Category | Subcategory | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. Study design |

| |

| 2. Publication status |

| |

| 3. Quality of evidence |

| |

| 4. Region |

| |

| 5. Setting (Health system funding) |

| |

| 6. Population |

| |

| 7. Intervention |

| |

| 8. Outcomes | 1. Safety |

|

| 2. Effectiveness | 1. Patient deterioration 2. Hospital associated infections 3. Medication safety 4. Pressure injuries 5. Falls | |

| 3. Efficiency |

| |

| 4. Timely access | 1. Time to receive care 2. Waiting times to access services | |

| 5. Patient experience |

| |

| 6. Health equity |

| |

| 9. Inequities |

| 1. Yes 2. No 3. Planned, but not reported |

| 1. Yes 2. No 3. Planned, but not reported | |

| 1. Yes 2. No 3. Planned, but not reported | |

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hales, C.; Chrystall, R.; Haase, A.M.; Jeffreys, M. Healthcare Service Interventions to Improve the Healthcare Outcomes of Hospitalised Patients with Extreme Obesity: Protocol for an Evidence and Gap Map. Methods Protoc. 2022, 5, 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps5030048

Hales C, Chrystall R, Haase AM, Jeffreys M. Healthcare Service Interventions to Improve the Healthcare Outcomes of Hospitalised Patients with Extreme Obesity: Protocol for an Evidence and Gap Map. Methods and Protocols. 2022; 5(3):48. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps5030048

Chicago/Turabian StyleHales, Caz, Rebecca Chrystall, Anne M. Haase, and Mona Jeffreys. 2022. "Healthcare Service Interventions to Improve the Healthcare Outcomes of Hospitalised Patients with Extreme Obesity: Protocol for an Evidence and Gap Map" Methods and Protocols 5, no. 3: 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps5030048

APA StyleHales, C., Chrystall, R., Haase, A. M., & Jeffreys, M. (2022). Healthcare Service Interventions to Improve the Healthcare Outcomes of Hospitalised Patients with Extreme Obesity: Protocol for an Evidence and Gap Map. Methods and Protocols, 5(3), 48. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps5030048