Study Protocol for a Pilot, Open-Label, Prospective, and Observational Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs Administered to Patients during Extracorporeal Circulation; Potential of In Vivo Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping to Optimise Pharmacotherapy

Abstract

:1. Introduction

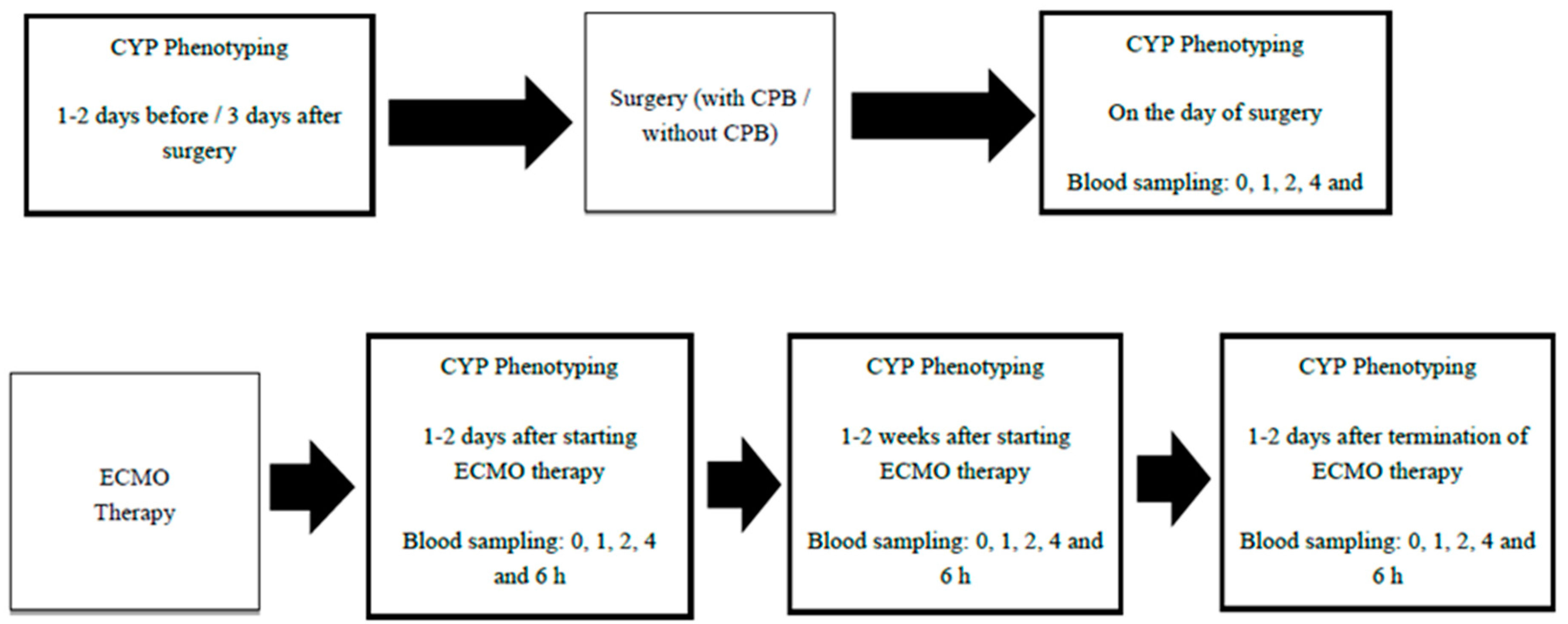

2. Experimental Design

3. Procedure

3.1. Objectives

- To describe the activities of CYP enzymes responsible for metabolism of clinically important drugs following CPB or ECMO support.

- To explore the impact of cytokine release during CPB and ECMO on the changes in the activities of CYP enzymes.

3.2. Participants

- Inclusion Criteria

- Age >18 years and <90 years;

- Eligible for elective mitral valve or aortic root surgeries involving CPB; or

- Eligible for ECMO support; or

- Eligible for elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

- Exclusion Criteria

- No consent;

- Pregnancy;

- Serum bilirubin >150 µmol/L;

- Already enrolled in an interventional ECMO-related research study (as per HREC approval);

- Ongoing massive blood transfusion requirement (>50% blood volume transfused in the previous 8 h);

- Therapeutic plasma exchange in the preceding 24 h;

- Adverse reaction to any elements of the study drug mixture;

- People with cognitive impairment or mental illness;

- Patients with significant coronary artery disease and/or aortic stenosis;

- Patients with liver disease/dysfunction;

- Using drugs that are known to be strong inhibitors or inducers of CYP enzymes (Flockhart table);

- Smokers.

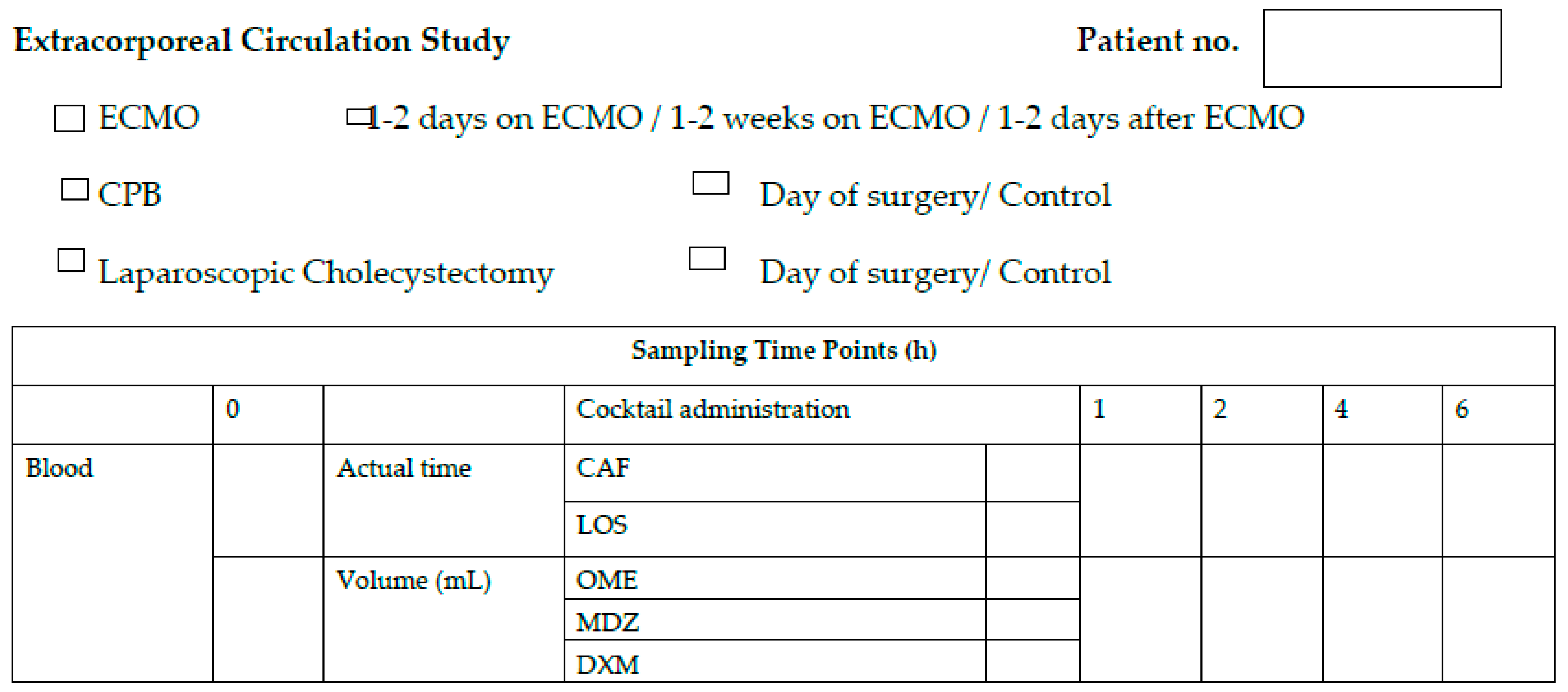

3.3. Phenotyping Cocktail Administration

- Caffeine: 50 mg, Caffeine Liquid 20 mg/mL, 2.5 mL will be administered to the patient;

- Dextromethorphan: 30 mg, 10 mg/5 mL, 15 mL via oral dosing syringe will be administered to the patient;

- Midazolam: 1 mg, 5 mg/5 mL, solution for injection: 1 mL in oral dosing syringe will be administered to the patient;

- Losartan: 5 mg, 50 mg tablet will be crashed using a mortar and pestle. Powder will be dissolved in 10 mL of water; 1 mL (5 mg) via oral dosing syringe will be administered to the patient;

- Omeprazole, 20 mg, one 20 mg tablet will be administered orally to the patient.

3.4. Data Analysis

- CYP2D6: Ratio of area under the plasma concentration—time curve of dextrorphan from 0 to 6 h after drug administration (AUC0–6h) to dextromethorphan AUC0–6h.

- CYP3A: Ratio of 1′-hydroxymidazolam AUC0-6h to midazolam AUC0–6h.

- CYP2C9: Ratio of E-3174 (losartan carboxy acid) AUC0-6h to losartan AUC0-6h.

- CYP1A2: Ratio of paraxanthine AUC0-6h to caffeine AUC0–6h (µmol/L).

- CYP2C19: Ratio of 5-hydroxyomeprazole AUC0-6h to omeprazole AUC0–6h.

4. Ethical and Dissemination

5. Discussion

- Enhancement of our collective understanding of the impact of drug metabolism on pharmacotherapy in psychiatry [38].

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Ethics Approval and Consent to Participate

Abbreviations

| CPB | Cardiopulmonary bypass |

| PK | Pharmacokinetics |

| Vd | Volume of Distribution |

| SIRS | Systemic Inflammatory Response Syndrome |

| MODL | Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndrome |

| CYP | Cytochrome P450 |

| ECMO | Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| TNF-α | Tumor necrotic factor-alpha |

| IL | Interleukin |

| VV-ECMO | Veno venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| VA-ECMO | Veno arterial extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| ICU | Intensive Care Unit |

| mg | milli grams |

| mL | milli litre |

| APACHE | Acute Physiology and Chronic Health Evaluation |

| SOFA | Sequential Organ Failure Assessment |

| LC-MS/MS | liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry |

| FDA | Food and Drugs Administration |

| EMA | European medicines agency |

| EC | extracorporeal circulations |

References

- Punjabi, P.P.; Taylor, K.M. The Science and Practice of Cardiopulmonary Bypass: From Cross Circulation to Ecmo and Sirs. Glob. Cardiol. Sci. Pract. 2013, 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Millar, J.E.; Fanning, J.P.; McDonald, C.I.; McAuley, D.F.; Fraser, J.F. The Inflammatory Response to Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (Ecmo): A Review of the Pathophysiology. Crit. Care 2016, 20, 387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khabar, K.S.; Elbarbary, M.A.; Khouqeer, F.; Devol, E.; Al-Gain, S.; Al-Halees, Z. Circulating Endotoxin and Cytokines after Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Differential Correlation with Duration of Bypass and Systemic Inflammatory Response/Multiple Organ Dysfunction Syndromes. Clin. Immunol. Immunopathol. 1997, 85, 97–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elahi, M.M.; Khan, J.S.; Matata, B.M. Deleterious Effects of Cardiopulmonary Bypass in Coronary Artery Surgery and Scientific Interpretation of Off-Pump’s Logic. Acute Card. Care 2006, 8, 196–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wan, S.; LeClerc, J.L.; Vincent, J.L. Inflammatory Response to Cardiopulmonary Bypass: Mechanisms Involved and Possible Therapeutic Strategies. Chest 1997, 112, 676–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirthler, M.; Simoni, J.; Dickson, M. Elevated Levels of Endotoxin, Oxygen-Derived Free Radicals, and Cytokines During Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Pediatr. Surg. 1992, 27, 1199–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McILwain, R.B.; Timpa, J.G.; Kurundkar, A.R.; Holt, D.W.; Kelly, D.R.; Hartman, Y.E.; Neel, M.L.; Karnatak, R.K.; Schelonka, R.L.; Anantharamaiah, G.M.; et al. Plasma Concentrations of Inflammatory Cytokines Rise Rapidly During Ecmo-Related Sirs Due to the Release of Preformed Stores in the Intestine. Lab. Investig. 2010, 90, 128–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gasz, B.; Lenard, L.; Racz, B.; Benko, L.; Borsiczky, B.; Cserepes, B.; Gal, J.; Jancso, G.; Lantos, J.; Ghosh, S.; et al. Effect of Cardiopulmonary Bypass on Cytokine Network and Myocardial Cytokine Production. Clin. Cardiol. 2006, 29, 311–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Chen, Q.; Yu, W.; Shen, J.; Gong, J.; He, C.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Gao, T.; Xi, F.; et al. Continuous Renal Replacement Therapy Reduces the Systemic and Pulmonary Inflammation Induced by Venovenous Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation in a Porcine Model. Artif. Organs 2014, 38, 215–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Golej, J.; Winter, P.; Schoffmann, G.; Kahlbacher, H.; Stoll, E.; Boigner, H.; Trittenwein, G. Impact of Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation Modality on Cytokine Release During Rescue from Infant Hypoxia. Shock 2003, 20, 110–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Adiraju, S.K.S.; Shekar, K.; Fraser, J.F.; Smith, M.T.; Ghassabian, S. Effect of Cardiopulmonary Bypass on Cytochrome P450 Enzyme Activity: Implications for Pharmacotherapy. Drug Metab. Rev. 2018, 50, 109–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Buylaert, W.A.; Herregods, L.L.; Mortier, E.P.; Bogaert, M.G. Cardiopulmonary Bypass and the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs. An Update. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 1989, 17, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cotogni, P.; Passera, R.; Barbero, C.; Gariboldi, A.; Moscato, D.; Izzo, G.; Rinaldi, M. Intraoperative Vancomycin Pharmacokinetics in Cardiac Surgery with or without Cardiopulmonary Bypass. Ann. Pharmacother. 2013, 47, 455–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, M.H.; Eells, S.J.; Tan, J.; Sheth, C.T.; Omari, B.; Flores, M.; Wang, J.; Miller, L.G. Prospective, Open-Label Investigation of the Pharmacokinetics of Daptomycin During Cardiopulmonary Bypass Surgery. Antimicrob. Agents Chemother. 2011, 55, 2499–2505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van Saet, A.; de Wildt, S.N.; Knibbe, C.A.; Bogers, A.D.; Stolker, R.J.; Tibboel, D. The Effect of Adult and Pediatric Cardiopulmonary Bypass on Pharmacokinetic and Pharmacodynamic Parameters. Curr. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 8, 297–318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sherwin, J.; Heath, T.; Watt, K. Pharmacokinetics and Dosing of Anti-Infective Drugs in Patients on Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation: A Review of the Current Literature. Clin. Ther. 2016, 38, 1976–1994. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Shekar, K.; Fraser, J.F.; Smith, M.T.; Roberts, J.A. Pharmacokinetic Changes in Patients Receiving Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation. J. Crit. Care 2012, 27, 741.e9–741.e18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sreevatsav Adiraju, S.K.; Shekar, K.; Fraser, J.F.; Smith, M.T.; Ghassabian, S. An Improved Lc-Ms/Ms Method for Simultaneous Evaluation of Cyp2c9, Cyp2c19, Cyp2d6 and Cyp3a4 Activity. Bioanalysis 2018, 10, 1577–1590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- European Medicines Agency. Guidance on Bioanalytical Method Validation (21 July 2011); EMA: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Ghassabian, S.; Chetty, M.; Tattam, B.N.; Chem, M.C.; Glen, J.; Rahme, J.; Stankovic, Z.; Ramzan, I.; Murray, M.; McLachlan, A.J. A High-Throughput Assay Using Liquid Chromatography-Tandem Mass Spectrometry for Simultaneous in Vivo Phenotyping of 5 Major Cytochrome P450 Enzymes in Patients. Ther. Drug Monit. 2009, 31, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghassabian, S.; Chetty, M.; Tattam, B.N.; Glen, J.; Rahme, J.; Stankovic, Z.; Ramzan, I.; Murray, M.; McLachlan, A.J. The Participation of Cytochrome P450 3a4 in Clozapine Biotransformation Is Detected in People with Schizophrenia by High-Throughput in Vivo Phenotyping. J. Clin. Psychopharmacol. 2010, 30, 629–631. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christensen, M.; Andersson, K.; Dalen, P.; Mirghani, R.A.; Muirhead, G.J.; Nordmark, A.; Tybring, G.; Wahlberg, A.; Yasar, U.; Bertilsson, L. The Karolinska Cocktail for Phenotyping of Five Human Cytochrome P450 Enzymes. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2003, 73, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fuhr, U.; Jetter, A.; Kirchheiner, J. Appropriate Phenotyping Procedures for Drug Metabolizing Enzymes and Transporters in Humans and Their Simultaneous Use in the “Cocktail” Approach. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 2007, 81, 270–283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donzelli, M.; Derungs, A.; Serratore, M.G.; Noppen, C.; Nezic, L.; Krahenbuhl, S.; Haschke, M. The Basel Cocktail for Simultaneous Phenotyping of Human Cytochrome P450 Isoforms in Plasma, Saliva and Dried Blood Spots. Clin. Pharmacokinet. 2014, 53, 271–282. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, X.; Shah, Y.; Cheung, C.; Guo, G.L.; Feigenbaum, L.; Krausz, K.W.; Idle, J.R.; Gonzalez, F.J. The Pregnane X Receptor Gene-Humanized Mouse: A Model for Investigating Drug-Drug Interactions Mediated by Cytochromes P450 3a. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2007, 35, 194–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomalik-Scharte, D.; Jetter, A.; Kinzig-Schippers, M.; Skott, A.; Sorgel, F.; Klaassen, T.; Kasel, D.; Harlfinger, S.; Doroshyenko, O.; Frank, D.; et al. Effect of Propiverine on Cytochrome P450 Enzymes: A Cocktail Interaction Study in Healthy Volunteers. Drug Metab. Dispos. 2005, 33, 1859–1866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eap, C.B.; Bondolfi, G.; Zullino, D.; Bryois, C.; Fuciec, M.; Savary, L.; Jonzier-Perey, M.; Baumann, P. Pharmacokinetic Drug Interaction Potential of Risperidone with Cytochrome P450 Isozymes as Assessed by the Dextromethorphan, the Caffeine, and the Mephenytoin Test. Ther. Drug Monit. 2001, 23, 228–231. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kashuba, A.D.M.; Nafziger, A.N.; Kearns, G.L.; Leeder, J.S.; Gotschall, R.; Rocci, M.L.; Kulawy, R.W.; Beck, D.J.; Bertino, J.S. Effect of Fluvoxamine Therapy on the Activities of Cyp1a2, Cyp2d6, and Cyp3a as Determined by Phenotyping. Clin. Pharmacol. Ther. 1998, 64, 257–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetter, A.; Fatkenheuer, G.; Frank, D.; Klaassen, T.; Seeringer, A.; Doroshyenko, O.; Kirchheiner, J.; Hein, W.; Schomig, E.; Fuhr, U.; et al. Do Activities of Cytochrome P450 (Cyp)3a, Cyp2d6 and P-Glycoprotein Differ between Healthy Volunteers and Hiv-Infected Patients? Antiviral Ther. 2010, 15, 975–983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frye, R.F.; Schneider, V.M.; Frye, C.S.; Feldman, A.M. Plasma Levels of Tnf-Alpha and Il-6 Are Inversely Related to Cytochrome P450-Dependent Drug Metabolism in Patients with Congestive Heart Failure. J. Card. Fail. 2002, 8, 315–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, B.M.; Song, I.H.; Adkison, K.K.; Borland, J.; Fang, L.; Lou, Y.; Berrey, M.M.; Nafziger, A.N.; Piscitelli, S.C.; Bertino, J.S., Jr. Evaluation of the Drug Interaction Potential of Aplaviroc, a Novel Human Immunodeficiency Virus Entry Inhibitor, Using a Modified Cooperstown 5 + 1 Cocktail. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2006, 46, 577–587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Wit, D.; Gelderblom, H.; Sparreboom, A.; den Hartigh, J.; den Hollander, M.; Konig-Quartel, J.M.; Hessing, T.; Guchelaar, H.J.; van Erp, N.P. Midazolam as a Phenotyping Probe to Predict Sunitinib Exposure in Patients with Cancer. Cancer Chemother. Pharmacol. 2014, 73, 87–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dees, E.C.; Watkins, P.B. Role of Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping in Cancer Treatment. J. Clin. Oncol. 2005, 23, 1053–1055. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gurley, B.J.; Swain, A.; Hubbard, M.A.; Williams, D.K.; Barone, G.; Hartsfield, F.; Tong, Y.; Carrier, D.J.; Cheboyina, S.; Battu, S.K. Clinical Assessment of Cyp2d6-Mediated Herb-Drug Interactions in Humans: Effects of Milk Thistle, Black Cohosh, Goldenseal, Kava Kava, St. John’s Wort, and Echinacea. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2008, 52, 755–763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Markowitz, J.S.; Donovan, J.L.; DeVane, C.L.; Taylor, R.M.; Ruan, Y.; Wang, J.S.; Chavin, K.D. Effect of St John’s Wort on Drug Metabolism by Induction of Cytochrome P450 3a4 Enzyme. J. Am. Med. Assoc. 2003, 290, 1500–1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williams, M.L.; Bhargava, P.; Cherrouk, I.; Marshall, J.L.; Flockhart, D.A.; Wainer, I.W. A Discordance of the Cytochrome P450 2c19 Genotype and Phenotype in Patients with Advanced Cancer. Br. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2000, 49, 485–488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zadoyan, G.; Rokitta, D.; Klement, S.; Dienel, A.; Hoerr, R.; Gramatte, T.; Fuhr, U. Effect of Ginkgo Biloba Special Extract Egb 761(R) on Human Cytochrome P450 Activity: A Cocktail Interaction Study in Healthy Volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2012, 68, 553–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hiemke, C.; Shams, M. Phenotyping and Genotyping of Drug Metabolism to Guide Pharmacotherapy in Psychiatry. Curr. Drug Deliv. 2013, 10, 46–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedersen, R.S.; Damkier, P.; Christensen, M.M.; Brosen, K. A Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping Cocktail Causing Unexpected Adverse Reactions in Female Volunteers. Eur. J. Clin. Pharmacol. 2013, 69, 1997–1999. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Type of Data | Details Recorded |

|---|---|

| Demographic Data |

|

| Clinical Data |

|

| Organ Function Fata |

|

| ECMO Data |

|

| CPB Data |

|

| Data Collection Form Extracorporeal Circulation Study (ECMO) | Patient No. | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Days on ECMO: Days off ECMO: | Date: Time: Food intake: Water intake: | |||

| Age | Sex (M/F) | Weight (Kg) | Height (cm) | |

| ICU Admission Diagnosis | APACHE III | SOFA | ||

| Days/hours on ECMO | ||||

| ECMO flow rate | ||||

| Type of ECMO | VA    VV Other VV Other | |||

| Pump | Josta Rota flow  Levotronix Centrimag  Cardiohelp  | |||

| Oxygenator | Quadrox Other (please specify) ……… | |||

| Serum bilirubin (µmol/L) | RRT: Yes/No If yes, please specify mode and flow below: | |||

| Midazolam Infusion Bolus (YES/NO) | Midazolam continuous infusion (YES/NO) | |||

| Serum Albumin (µmol/L) | CVVH | CVVHDF | SCUF | |

| Serum Creatinine (µmol/L) | EDD | IHD | OTHER | |

| Total Protein (g/L) | Effluent Flow Rate (mL/h) | |||

| Blood Urea (mmol/L) | Blood Flow Rate (mL/h) 8h Creatinine Clearance | |||

| Blood Product Transfusion Details | 24 h Fluid Balance | |||

| Data Collection form Extracorporeal Circulation Study (CPB) | Patient No. Date: Time: Food intake: Water intake: | ||

| Age | Sex (M/F) | Weight (Kg) | Height (cm) |

| ICU Admission Diagnosis | |||

| Hours on CPB | |||

| Type of CPB | |||

| Hypothermia | |||

| Blood pump flow rate | |||

| Type of membrane | |||

| Serum bilirubin (µmol/L) | 8 h Creatinine Clearance | ||

| Serum Creatinine (µmol/L) | |||

| Serum Albumin (g/L) | |||

| Total Proteins (g/L) | |||

| Blood Urea (mmol/L) | |||

© 2019 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Adiraju, S.K.S.; Shekar, K.; Tesar, P.; Naidoo, R.; Rapchuk, I.; Belz, S.; Fraser, J.F.; Smith, M.T.; Ghassabian, S. Study Protocol for a Pilot, Open-Label, Prospective, and Observational Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs Administered to Patients during Extracorporeal Circulation; Potential of In Vivo Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping to Optimise Pharmacotherapy. Methods Protoc. 2019, 2, 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2020038

Adiraju SKS, Shekar K, Tesar P, Naidoo R, Rapchuk I, Belz S, Fraser JF, Smith MT, Ghassabian S. Study Protocol for a Pilot, Open-Label, Prospective, and Observational Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs Administered to Patients during Extracorporeal Circulation; Potential of In Vivo Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping to Optimise Pharmacotherapy. Methods and Protocols. 2019; 2(2):38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2020038

Chicago/Turabian StyleAdiraju, Santosh Kumar Sreevatsav, Kiran Shekar, Peter Tesar, Rishendran Naidoo, Ivan Rapchuk, Stephen Belz, John F Fraser, Maree T Smith, and Sussan Ghassabian. 2019. "Study Protocol for a Pilot, Open-Label, Prospective, and Observational Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs Administered to Patients during Extracorporeal Circulation; Potential of In Vivo Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping to Optimise Pharmacotherapy" Methods and Protocols 2, no. 2: 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2020038

APA StyleAdiraju, S. K. S., Shekar, K., Tesar, P., Naidoo, R., Rapchuk, I., Belz, S., Fraser, J. F., Smith, M. T., & Ghassabian, S. (2019). Study Protocol for a Pilot, Open-Label, Prospective, and Observational Study to Evaluate the Pharmacokinetics of Drugs Administered to Patients during Extracorporeal Circulation; Potential of In Vivo Cytochrome P450 Phenotyping to Optimise Pharmacotherapy. Methods and Protocols, 2(2), 38. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2020038