Air Puff System Fundamentals for Reproducible Eyeblink Conditioning Research

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

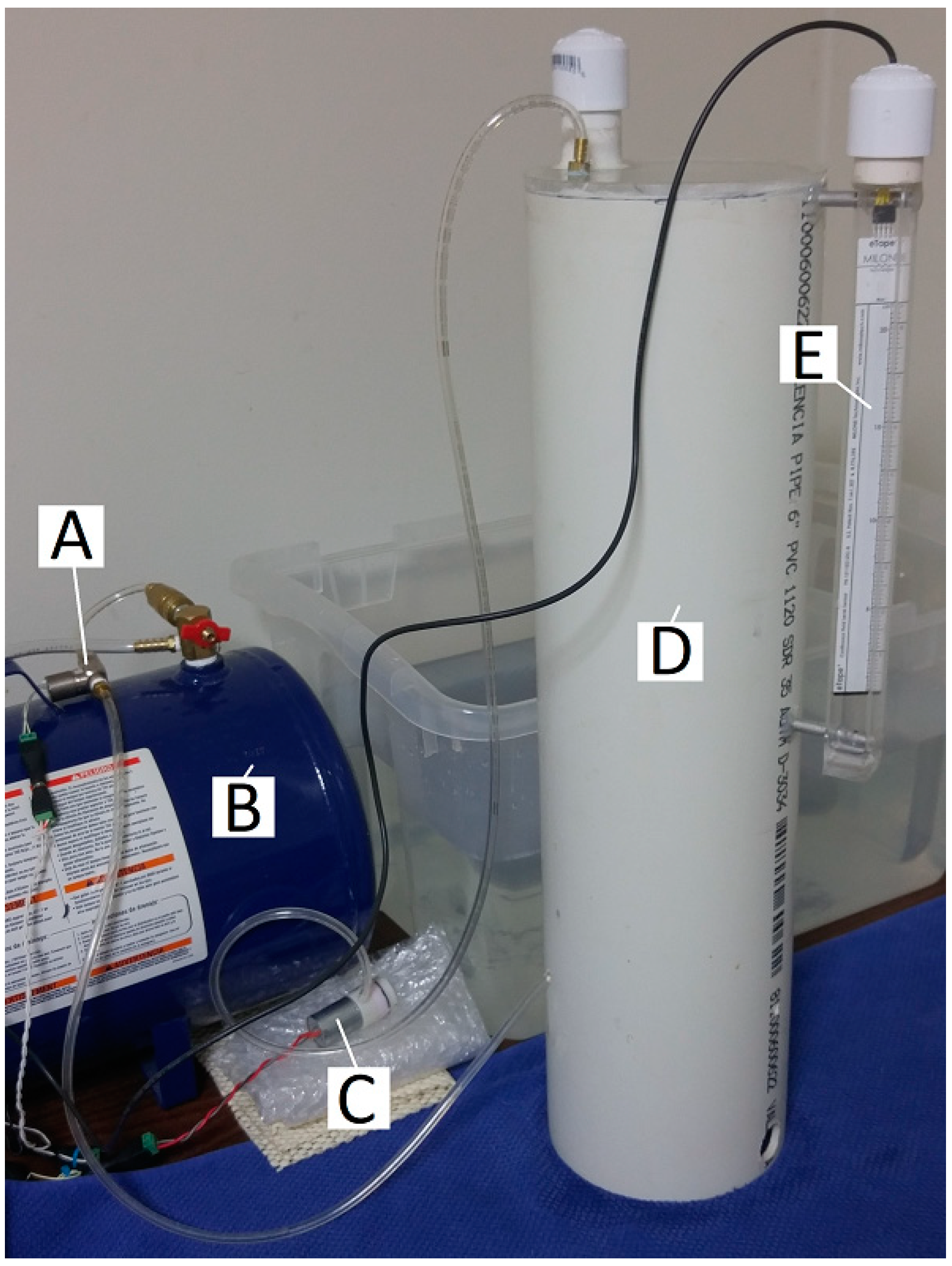

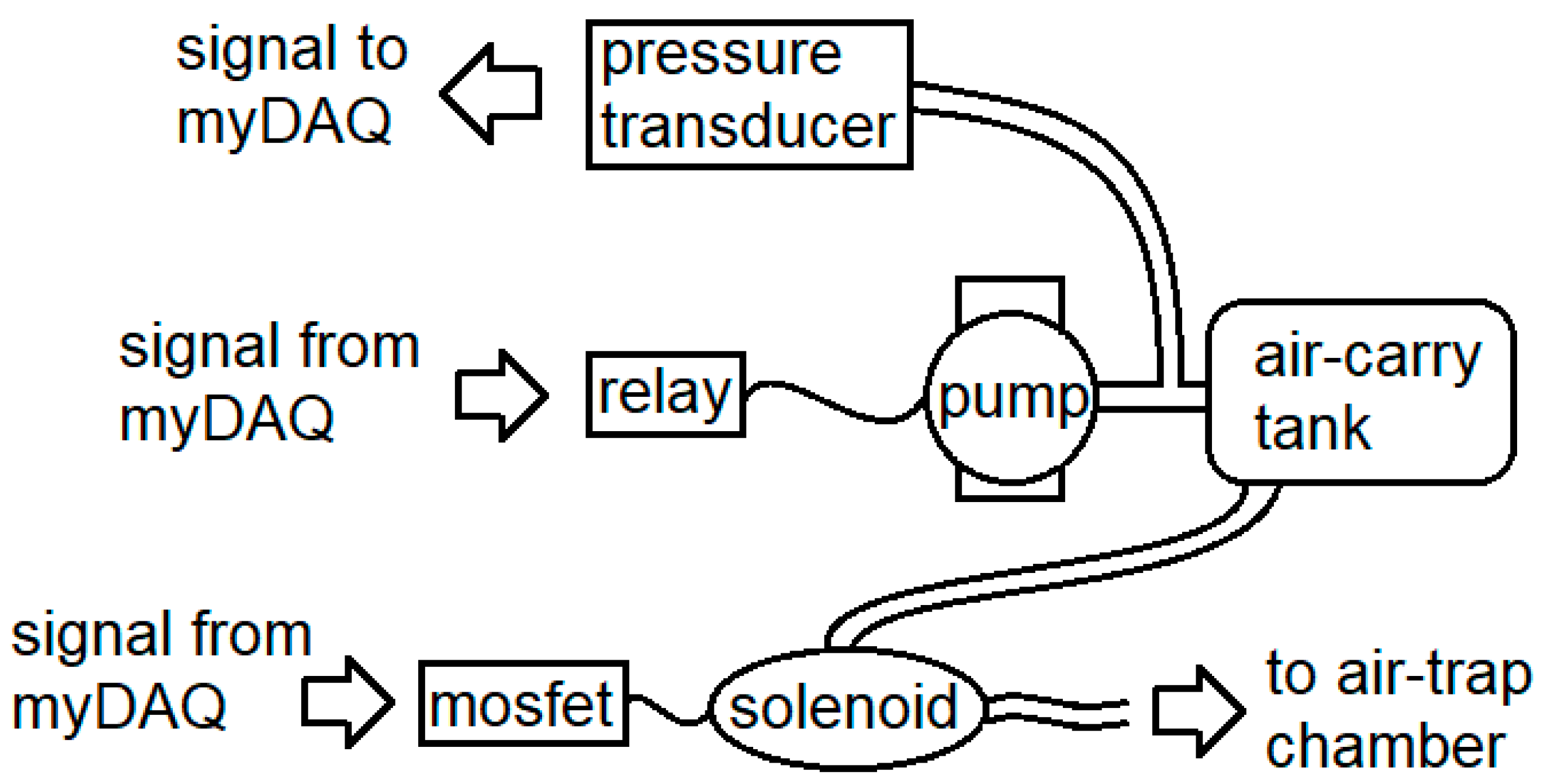

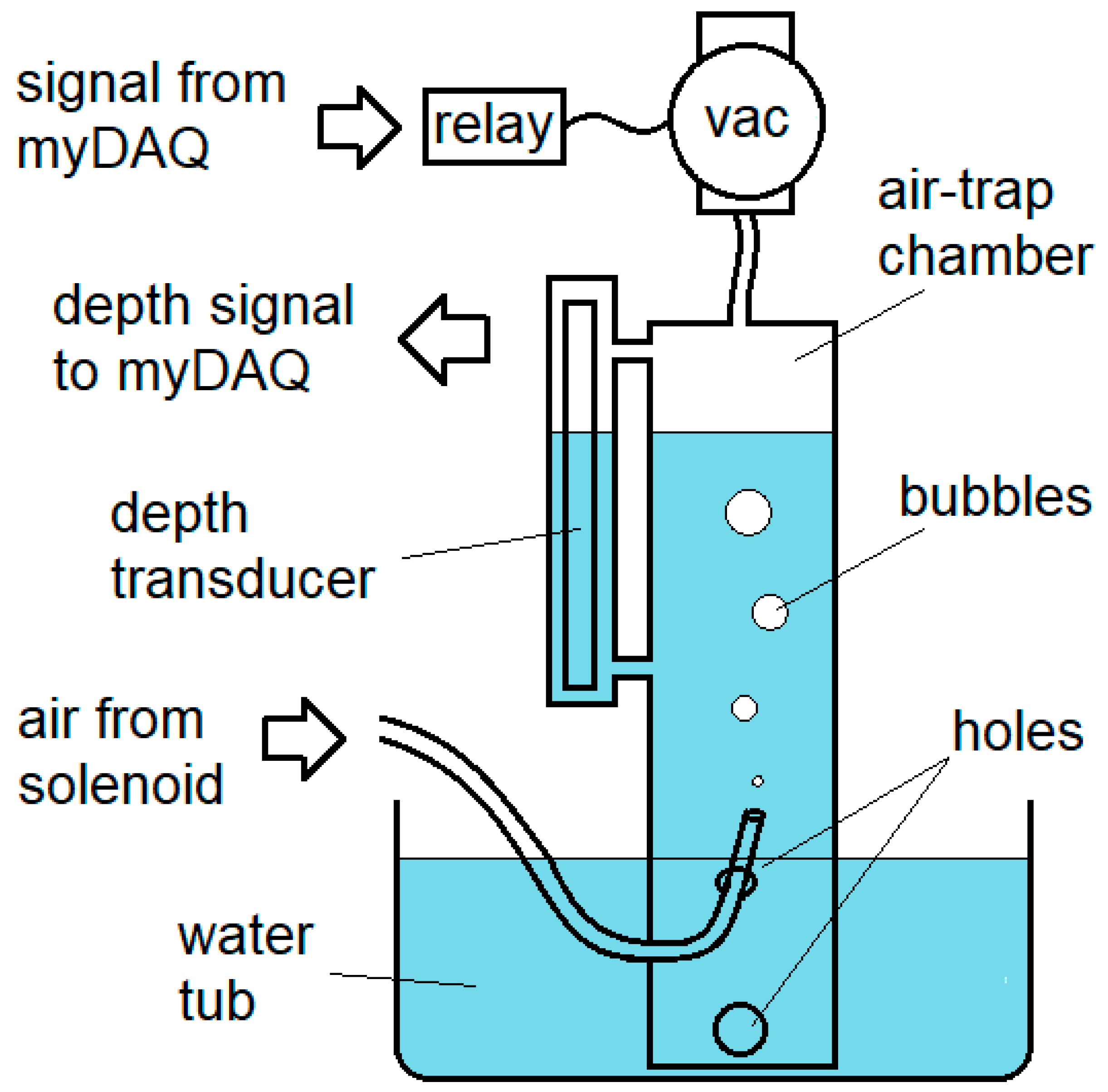

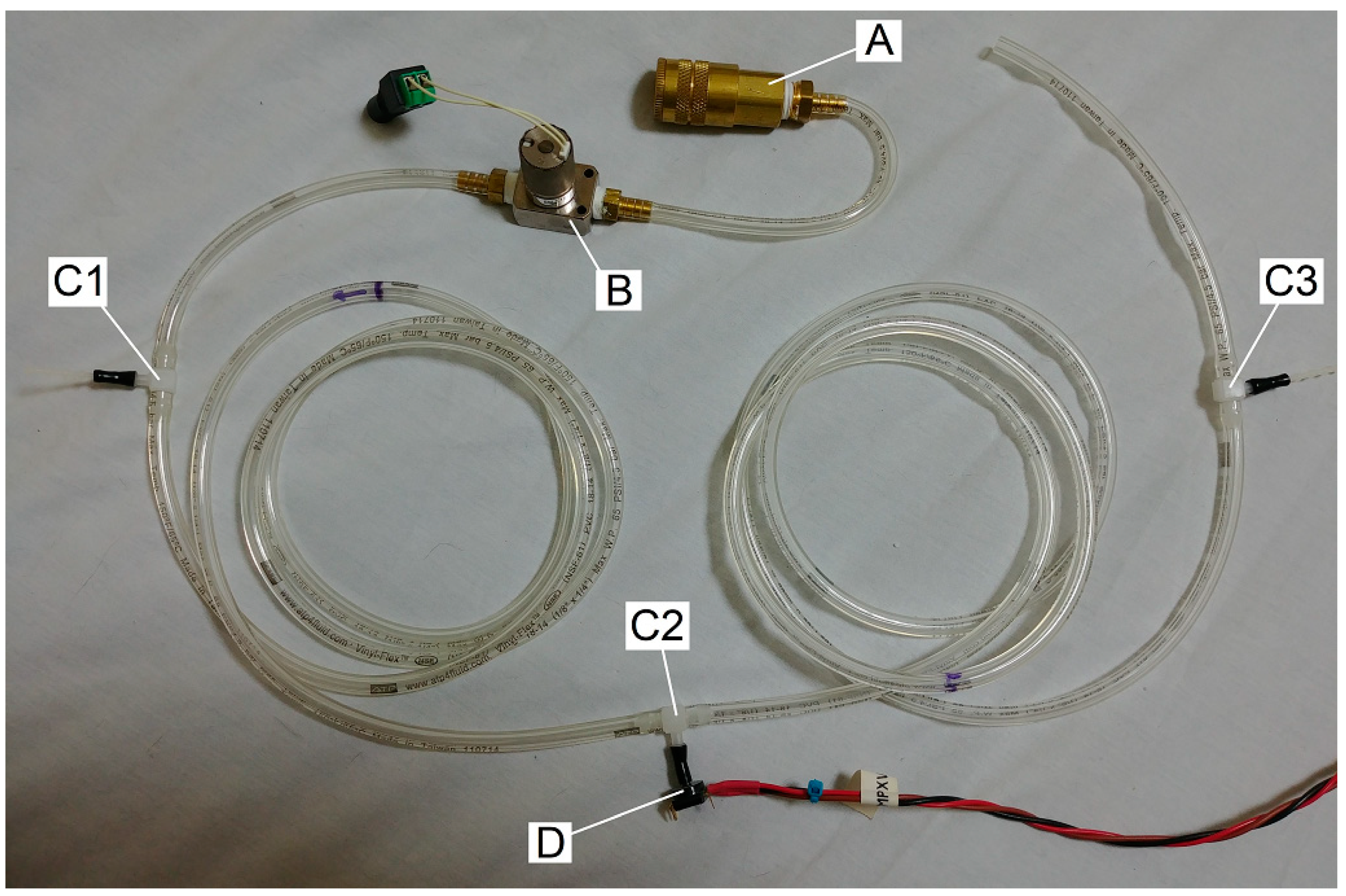

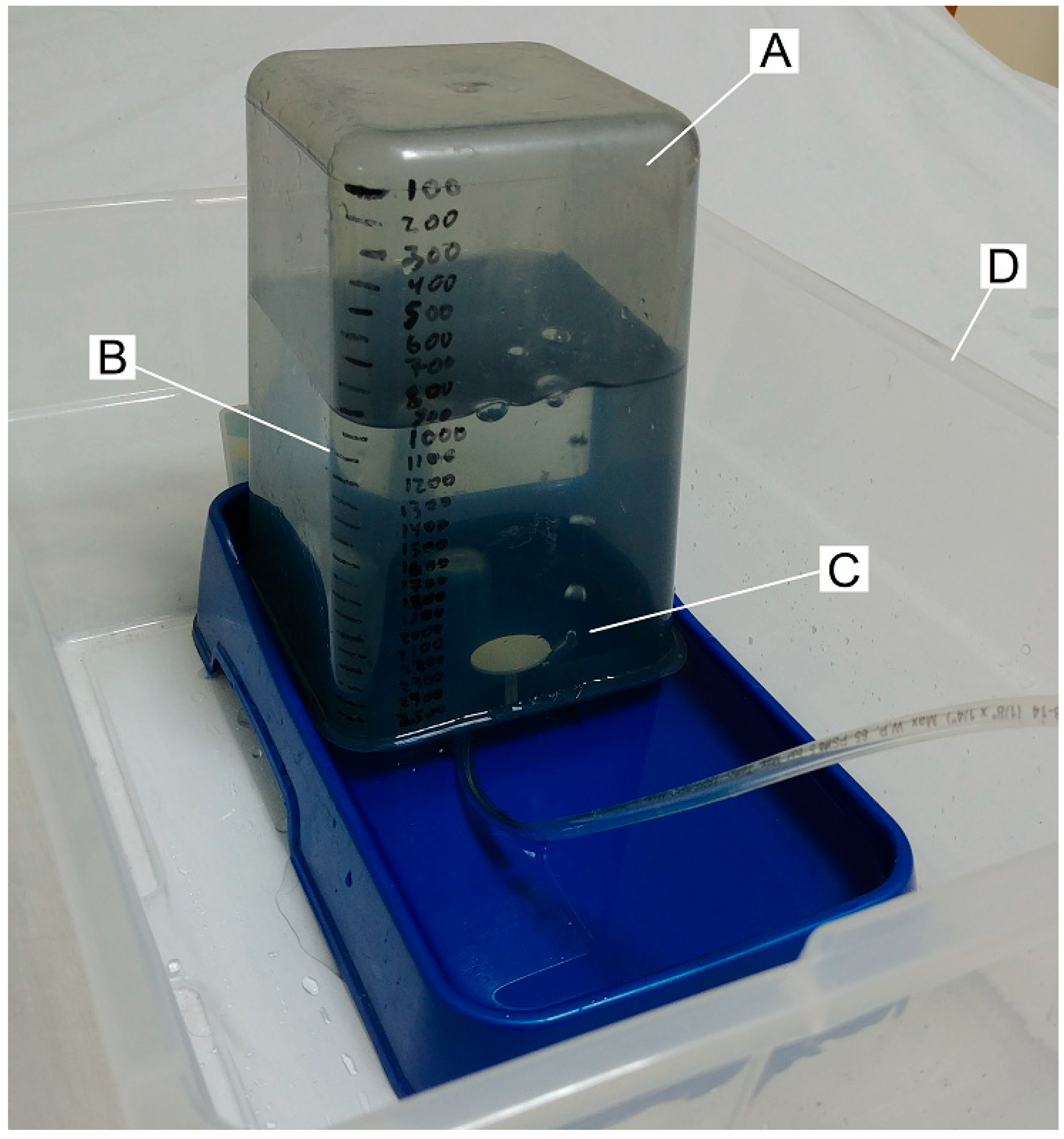

2.1. Automated Flow Rate Measurements

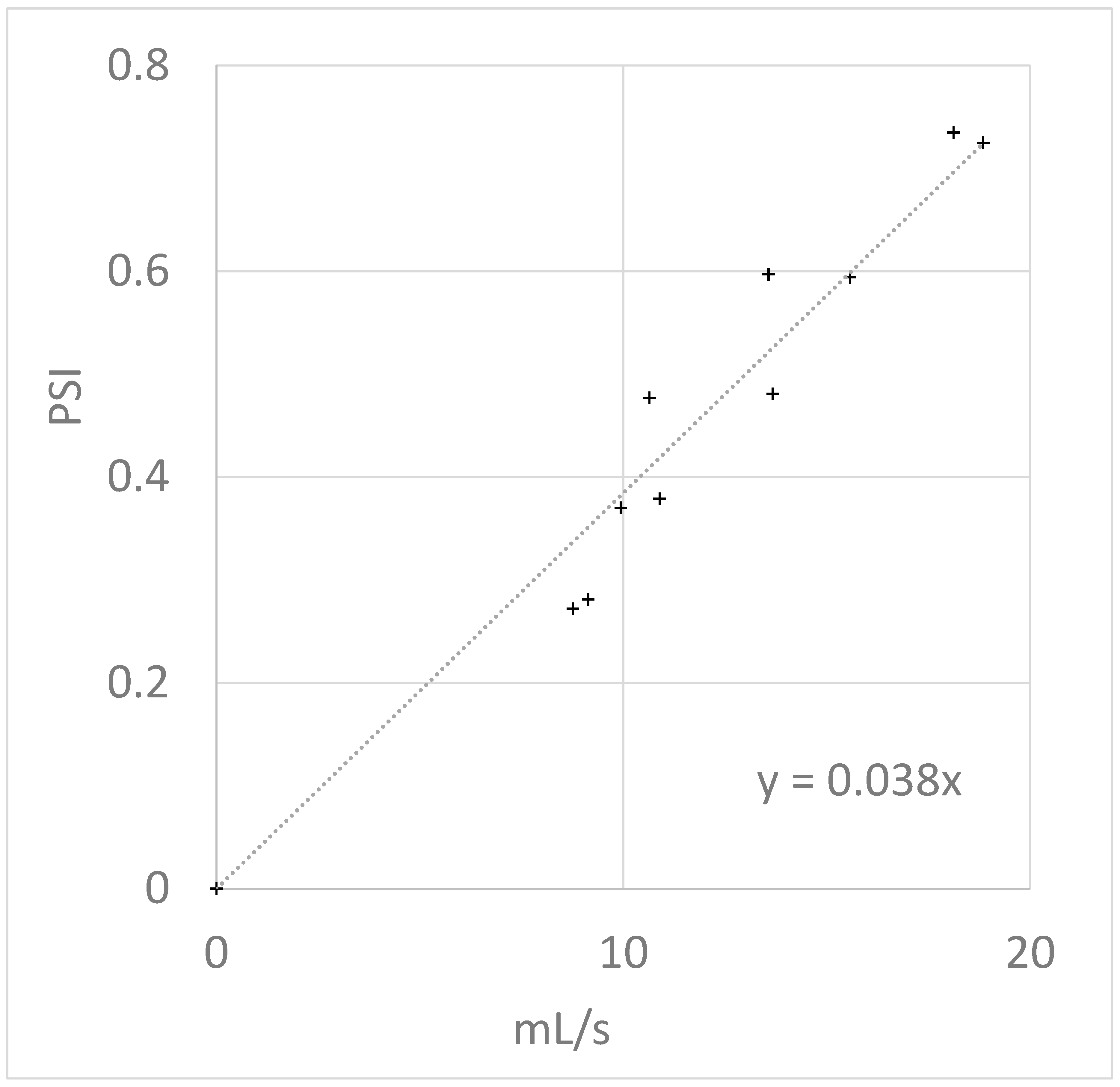

2.2. Intra-Tube Pressure Dynamics

3. Results

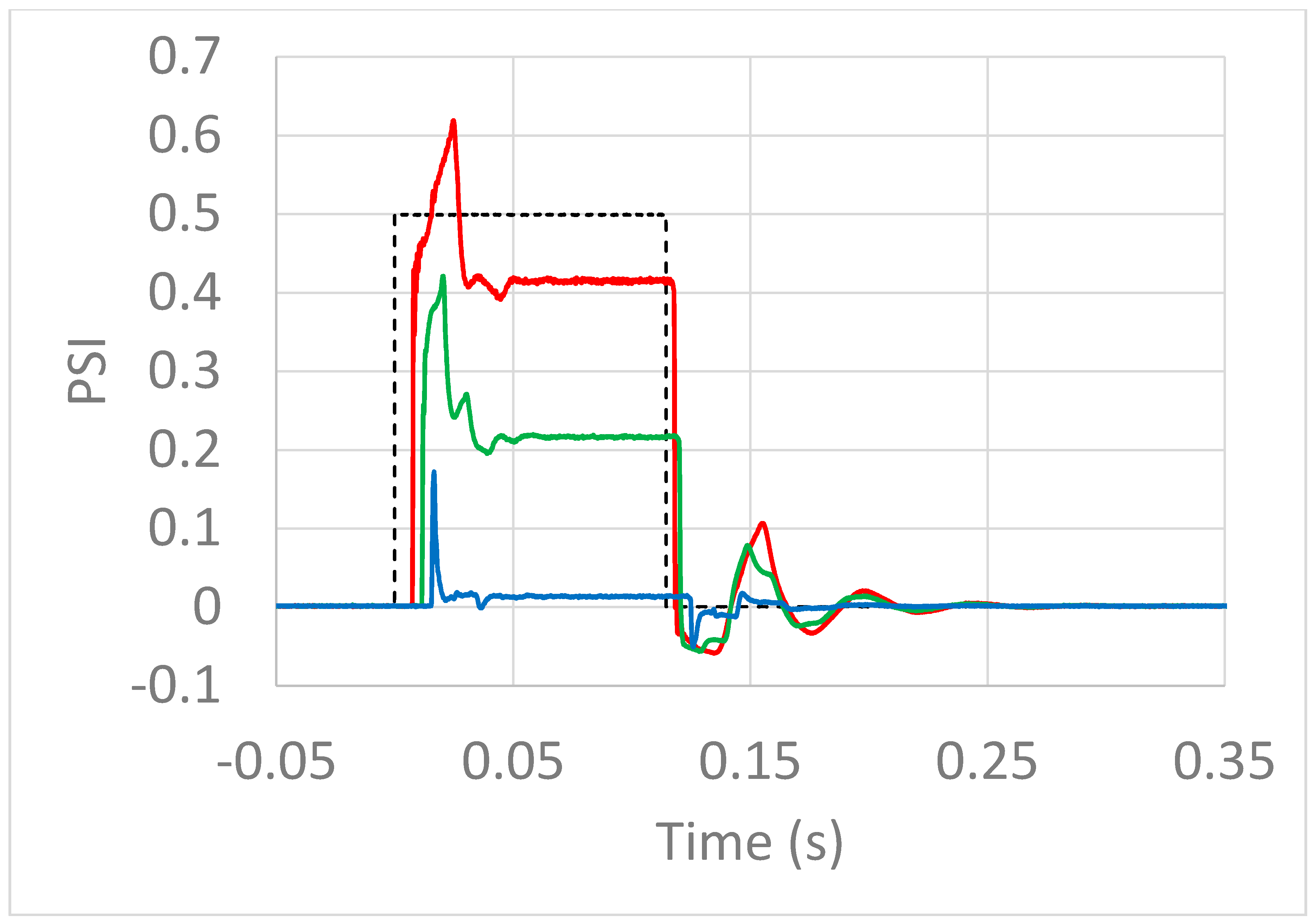

3.1. What’s Really Happening within the Tube

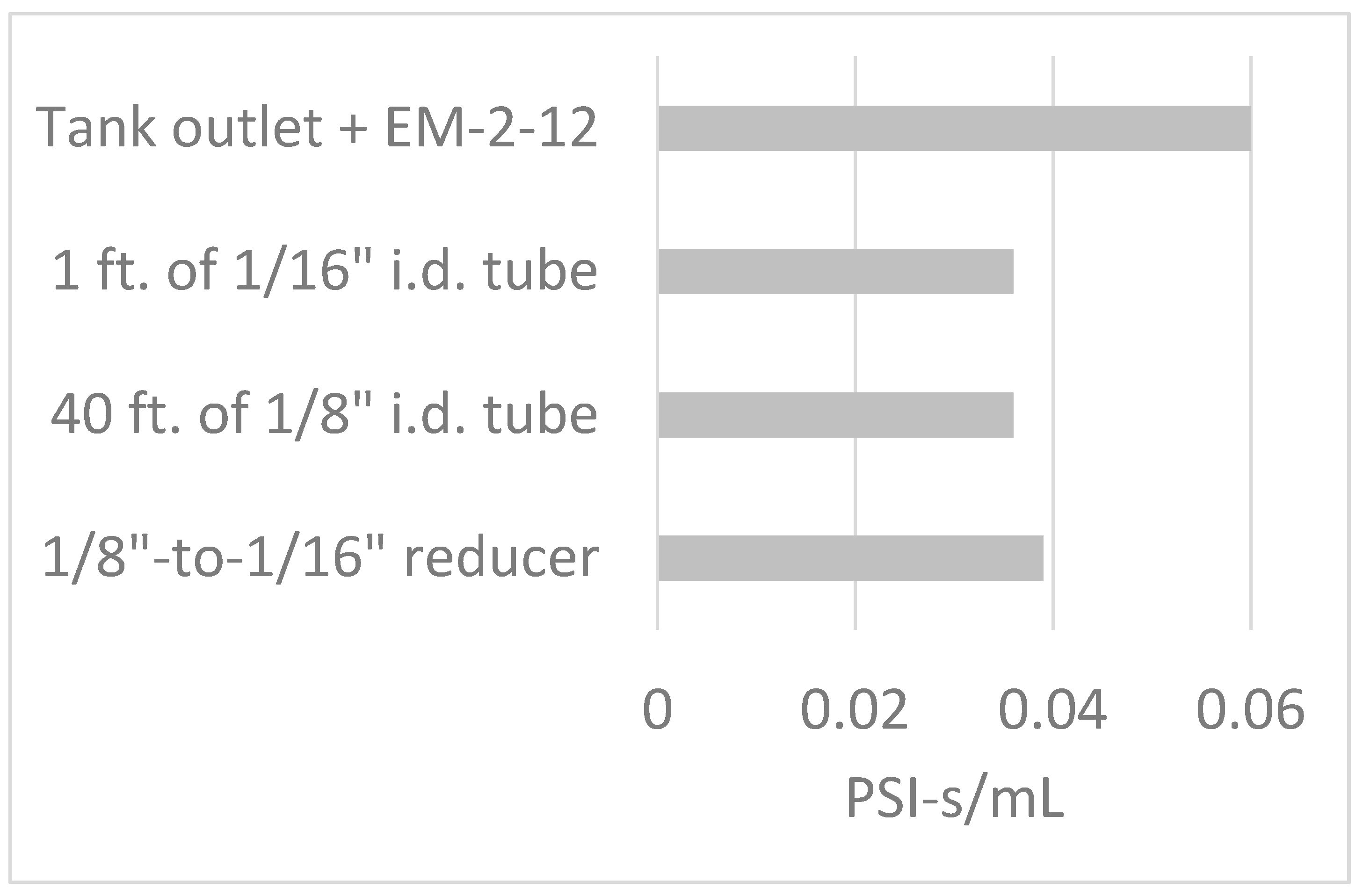

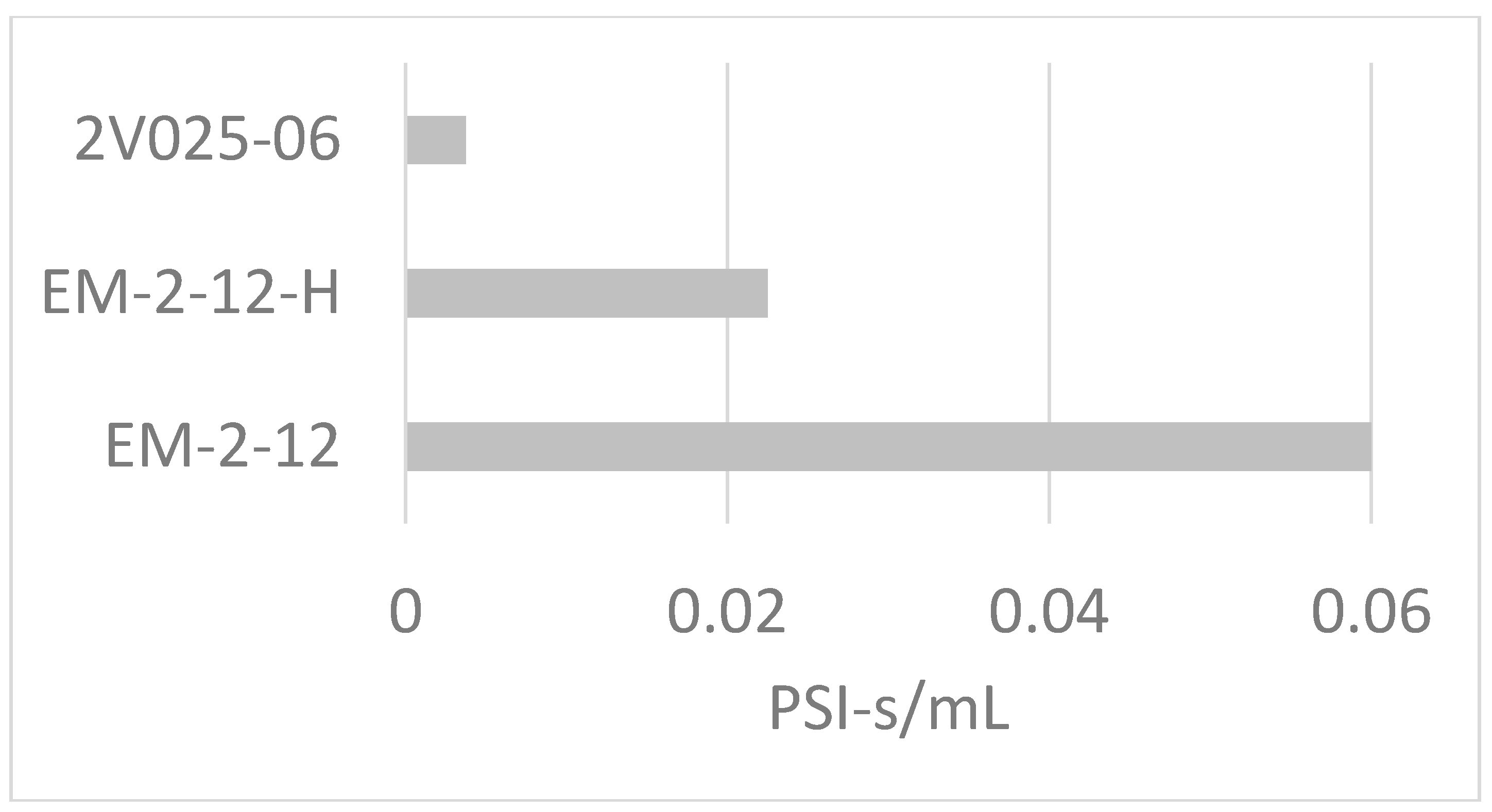

3.2. The “Electronic–Hydraulic Analogy” Model of Pressure, Flow, and Resistance to Flow

- (a)

- If the resistance of 1 foot of tubing is R1foot, the resistance of 10 feet of tubing will be approximately the sum of 10 such resistances, or 10R1foot;

- (b)

- Doubling the resistance at a given pressure should approximately halve the flow rate;

- (c)

- Doubling the pressure should approximately double the flow rate.

- (a)

- A single coupler such as a plastic reducing adapter is comparably resistive to a foot of 1/16″ i.d. tubing;

- (b)

- A single foot of 1/16″ i.d. tubing is comparably resistive to 40 feet of 1/8″ i.d. tubing;

- (c)

- The solenoid and tank outlet contribute to the resistance significantly in and of themselves.

- (d)

- Resistance among solenoids that appear similar can vary by more than one order of magnitude, so choice of solenoid can greatly influence exactly what PSI will be required to achieve a desired strength of puff. Note: the 2V025-06 is included as a high-flow-rate example only; it is not designed for quiet operation.

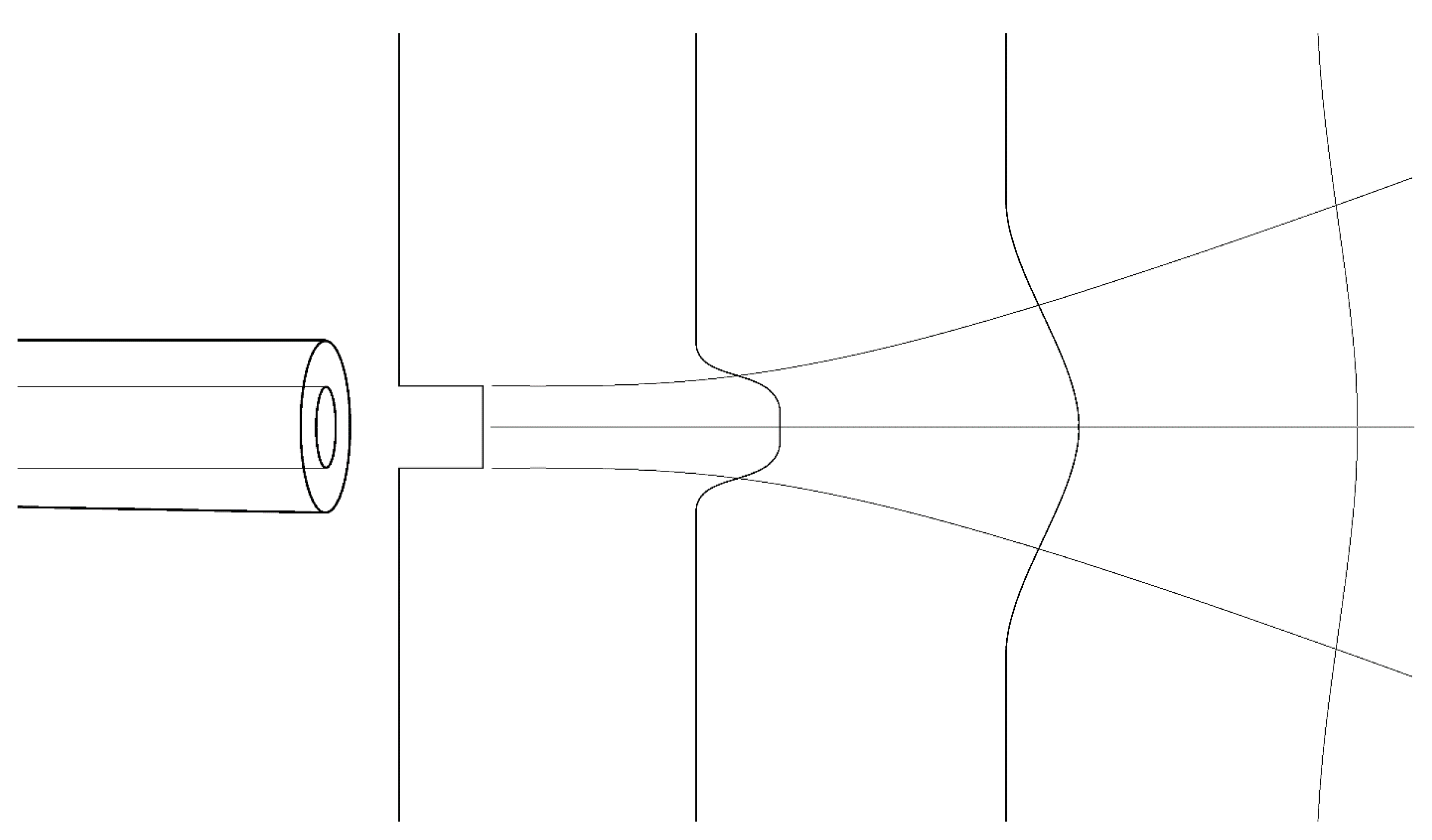

3.3. “Puff” Geometry

- There is a near-field region in which the flow remains somewhat collimated, and square in velocity profile, for a short distance (~10 times the aperture diameter).

- The flow then diverges with a half-angle of approximately 12°, gradually adopting a Gaussian velocity profile.

- The peak (axial) velocity drops off monotonically toward zero with distance from the aperture as the velocity profile broadens laterally.

- The flow profile shape, half-width, and peak velocity all vary with distance;

- This variation is particularly interesting at precisely the separation distances typically chosen by experimenters (i.e., “close to the eye”, where the flow is transitioning from the near- to far-field region);

- Where this interesting transition happens depends upon the diameter of the exit orifice of the system.

4. Discussion

4.1. What Flow Rate Should One Choose?

- ▪

- 100 mL/s is too strong by far;

- ▪

- 10 mL/s is rather strong but not obviously unacceptable;

- ▪

- 1 mL/s is perceptible but subtle.

4.2. Measuring Flow Rate at Your Workbench

5. Conclusions

- The make and model of the solenoid or off-the-shelf system used;

- the length and inner diameter of the tubing used;

- the exit aperture diameter, if different from that of the tubing;

- the tubing-eye separation distance.

- 5.

- A direct measurement of the flow rate of the system, as the experimenter, with system in hand, is uniquely positioned to best determine this number.

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Error Analysis

Appendix A.1. Adiabatic Expansion and Subsequent Temperature Equilibration

Appendix A.2. Varying Height within Water Column

Appendix A.3. Reynolds Number

Appendix A.4. Calibration

Appendix A.5. Steady-State Approximation of Transient Puffs

References

- Rehman, I.; Rehman, C.I. Classical Conditioning. StatPearls Publishing: Treasure Island, FL, USA, 2018. Available online: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470326/ (accessed on 24 January 2019).

- LeDoux, J.E. Emotion Circuits in the Brain. Annu. Rev. Neurosci. 2000, 23, 155–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCormick, D.A.; Thompson, R.F. Cerebellum: Essential Involvement in the Classically Conditioned Eyelid Response. Science 1984, 223, 296–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeo, C.H.; Hardiman, M.J.; Glickstein, M. Discrete Lesions of the Cerebellar Cortex Abolish the Classically Conditioned Nictitating Membrane Response of the Rabbit. Behav. Brain Res. 1984, 13, 261–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, J.H. Cerebellar learning mechanisms. Brain Res. 2015, 1621, 260–269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, Y.; Lei, C.; Feng, H.; Sui, J. The neural circuitry and molecular mechanisms underlying delay and trace eyeblink conditioning in mice. Behav. Brain Res. 2015, 278, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siegel, J.J.; Taylor, W.; Gray, R.; Kalmbach, B.; Zemelman, B.V.; Desai, N.S.; Johnston, D.; Chitwood, R.A. Trace Eyeblink Conditioning in Mice Is Dependent upon the Dorsal Medial Prefrontal Cortex, Cerebellum, and Amygdala: Behavioral Characterization and Functional Circuitry. eNeuro 2015, 2, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reeb-Sutherland, B.C.; Fox, N.A. Eyeblink conditioning: A non-invasive biomarker for neurodevelopmental disorders. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2015, 45, 376–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ten Brinke, M.M.; Boele, H.; Spanke, J.K.; Potters, J.; Kornysheva, K.; Wulff, P.; IJpelaar, A.C.H.G.; Koekkoek, S.K.E.; De Zeeuw, C.I. Evolving Models of Pavlovian Conditioning: Cerebellar Cortical Dynamics in Awake Behaving Mice. Cell Rep. 2015, 13, 1977–1988. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albergaria, C.; Silva, N.T.; Pritchett, D.L.; Carey, M.R. Locomotor Activity Modulates Associative Learning in Mouse Cerebellum. Nat. Neurosci. 2018, 21, 725–735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Spence, K.W.; Platt, J.R. UCS Intensity and Performance in Eyelid Conditioning. Psychol. Bull. 1966, 65, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spence, K.W.; Taylor, J. Anxiety and strength of the UCS as determiners of the amount of eyelid conditioning. J. Exp. Psychol. 1951, 42, 183–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oswald, B.B.; Knuckley, B.; Mahan, K.; Sanders, C.; Powell, D.A. Prefrontal control of trace eyeblink conditioning in rabbits (Oryctolagus cuniculus) II: Effects of type of unconditioned stimulus (airpuff vs. periorbital shock) and unconditioned stimulus intensity. Physiol. Behav. 2009, 96, 67–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marshall-Goodell, B.; Kehoe, E.J.; Gormezano, I. Laws of the unconditioned reflex in the rabbit nictitating membrane preparation. Psychobiology 1992, 20, 229–237. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, M.C. CS-US interval and US intensity in classical conditioning of the rabbit’s nictitating membrane response. J. Comp. Physiol. Psychol. 1968, 66, 679–687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Donegan, N.H.; Wagner, A.R. Conditioned diminution and facilitation of the UR: A sometimes opponent-process interpretation. In Classical Conditioning; Gormezano, I., Prokasy, W.F., Thompson, R.F., Eds.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.: Hillsdale, NJ, USA, 1987; pp. 339–369. [Google Scholar]

- Coyle, W.L. Predicting playing frequencies for clarinets: A comparison between numerical simulations and simplified analytical formulas. J. Acoust. Soc. Am. 2015, 138, 2770–2781. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akers, A.; Gassman, M.; Smith, R. Hydraulic Power System Analysis; Taylor & Francis: New York, NY, USA, 2006; Chapter 13. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, A.A. Simplified Method for Analyzing Circuits by Analogy. Mach. Des. 1969, 173–177. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, R.D. Applied Fluid Dynamics Handbook; Krieger Publishing Company: Malabar, FL, USA, 2003. [Google Scholar]

© 2019 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Reitz, F. Air Puff System Fundamentals for Reproducible Eyeblink Conditioning Research. Methods Protoc. 2019, 2, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2010014

Reitz F. Air Puff System Fundamentals for Reproducible Eyeblink Conditioning Research. Methods and Protocols. 2019; 2(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleReitz, Frederick. 2019. "Air Puff System Fundamentals for Reproducible Eyeblink Conditioning Research" Methods and Protocols 2, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2010014

APA StyleReitz, F. (2019). Air Puff System Fundamentals for Reproducible Eyeblink Conditioning Research. Methods and Protocols, 2(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/mps2010014