Landscape Change in Japan from the Perspective of Gardens and Forest Management

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results

3.1. Natural Environment

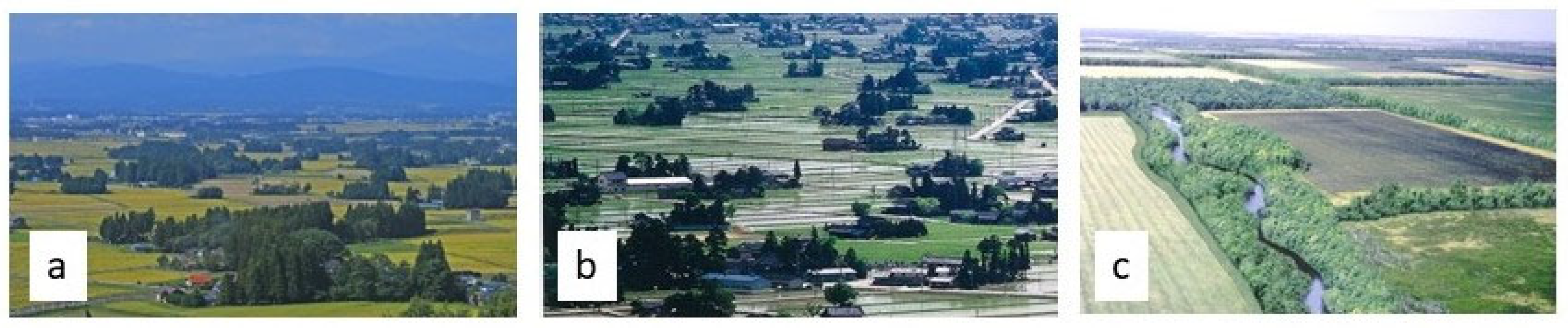

3.2. Formation of the Scenery

| Japanese Era Classification | Town and/or Region, Garden, Landscaper | Canopy Texture of Forest | Political Situation/Foreign Countries | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ancient | Kofun period, BC 300~538; Asuka (592–710) | Mainly western Japan/the Asuka (around Nara Prefecture) Horyuji-temple was built. | Broad-leaved forests were dominant. Big conifers were used for construction. No record for forest plantation was found. | The advanced flame of the Sui & Tang (started from 630~) dynasty of China |

| Nara period (710–784) | Nara prefecture and its vicinity/almost no literature recorded/exploitative forestry | Sugi-cedar, Hinoki-cypress, and Keyaki (Zelkova sp.) were used in the literature. Not a smooth forest canopy resulted in cutout in the forest | Advanced knowledge (the Feng Shui) was introduced from the Tang dynasty. Amidst social unrest, Pure Land Buddhism emerged. | |

| Heian period (794–1185) | Kyoto City (approximately 400 years) had almost no major battles, except in the Tohoku district. Sinden-zukuri (the residence of the aristocracy was built.). | In the Heian period, the Shinden-zukuri style was established for nobles’ residences with gardens. | A Japanese envoy to Tang Dynasty China (630~1131). | |

| Medieval | Kamakura and Muromachi, 1185–1466 | Kamakura city (Kanagawa prefecture)/Shoin-zukuri-traditional style of Japanese residential architecture. Dry garden style created by the monk, Mr. Muso Soseki. | Over-harvested near Kamakura and poor scenery/Man-made forests were found around SATOYOMA * | Goryeo (Korea), Attacked by the Yuan dynasty (China) |

| Muromachi/the Onin-Bunmei Wars 1466– | Western Japan, mainly Kyoto city and its vicinity. The “Higashi-yama” culture had been established. | After the Ōnin War, the Warring States period began, and the harvesting of cedar and cypress trees intensified. | Battles destroyed forests near the village and town. The concept of impermanence revived during the late Heian and Kamakura periods due to persistent social unrest and natural disasters. | |

| Azuchi-Momoyama | The sukiya-style architecture suited to the tea ceremony was created. | Smooth canopy, such as “Yoshino” forestry. Strolling garden with a pond had started. | The Shogun, Hideyoshi Toyotomi, could manage most timber in Japan. He tried to invade to the Korean region. | |

| Early modern ** | early Edo 1603–1650 | Edo (=Tokyo/ Kanto plain region). Japanese feudal lords were constructed, finally the garden occupied about half area of Edo city. | Forests near big towns were sparse or bare due to partial harvesting of timber for recovery after fires. | Japanese isolationism during the Edo period (1639–1854), except for the Netherlands (Korea and the Ming dynasty of China). The population of Edo reached one million. |

| mid Edo 1650–1750 | Mountain products were used as tribute and also commercialized, supplying firewood, charcoal, timber, and other goods to cities. Cultivated land increased, and large quantities of cut grass were used as fertilizer. This cutting of grass created grassy hills. To facilitate these uses, the “communal land” system was established, and boundaries were defined. Furthermore, afforestation by the domains and the shogunate progressed. | Characterized by mountain-style gardens skillfully incorporating stonework and the “naturalistic landscape” approach to garden design that realistically portrays natural scenery. Pond-stroll garden and its maturity. | The “Edict on Compassion for Living Creatures” issued by the 5th shogun, Tsunayoshi, contained some excessive elements, but its emphasis on “cherishing life” did have a influence on the subsequent approach to meat consumption. | |

| late Edo 1750–1868 | Forests near big cities were getting sparse in part of Japan (but rare in Hokkaido). | Distinctive local landscapes with forest canopy (Table 2) | Without any big battles occurring, feudal lords across the land implemented forest resource management suited to their respective domains. | |

| Modern times | Meiji-Taisho period 1868–1912~1926 | (1) Emperor’s forest; (2) Ordinal people’s forests/Forest resource management for the Imperial Family aimed to create forests that emulate nature, differing from other forests. French and English type gardens were introduced, | From the exploitative forestry practices of the Edo period onwards, forest management primarily modelled on German forestry was implemented to bolster the nation’s resources. | Meiji Restoration & Revolution. Education and control of the populace were carried out to achieve the goals of enriching the nation, strengthening the military, and promoting industry and commerce. |

| Showa 1926~1945, After WWII 1945~ | Whole Japan/Large-scale coniferous afforestation was carried out across Japan, primarily in publicly owned forests. Particularly in Hokkaido, large-scale planting of the non-native larch species Larix gmelinii was undertaken, though many sites proved unproductive. | Enlarged reforestation usually loses its distinctive canopy texture. As a result, the distinctive forest management practices traditionally carried out in each region have undermined the formation of local landscapes. | After the 1960s, the “Energy Revolution” progressed, and the value of domestic lumber has been decreasing. Furthermore, changes in dietary habits, coupled with wildlife conservation management and population decline, have culminated in a disaster. We are now compelled to rebuild the very fabric of society. | |

| to date | Whole Japan/called a “green desert” due to the aftereffects of monoculture plantation with conifers. Deer populations have surged dramatically in recent years, with bark stripping becoming increasingly prevalent, leaving planted trees in a state of near-total devastation. | Without tending practices for the man-made forests, some parts of the forest canopy were destroyed by strong winds, heavy rain, and/or snow. Deer browsing along ridgelines leads to denudation, which often results in landslides during heavy rainfall. | With the rapid progress of globalization, some man-made forests appear to be lacking. Some villages are missing due to underuse with low population. The administrative side failed to manage wildlife populations adequately. | |

| Density | Rotation | Thinning | Region | Products |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low | long | growth regulation of individuals | Obi | Beam, deck wood |

| short | very rare, few | Hita, Tenryu, Oguni | pole, ordinary timber | |

| Inter-Mediate | long | few | Chidu | high quality timber, barrel |

| long | often tending | National forest | ordinal timber | |

| High | short | few | Ome, Owase | pole for flatwork |

| many times from early stage | Kitayama | pole for decoration, handrail | ||

| long | many times from early stage | Yoshino | high quality timber, large sized trees |

3.3. Living Environments and the “Garden”: A Comparative Perspective with the West

3.3.1. Ancient Period

3.3.2. Medieval Period

3.3.3. Early Modern Period

3.3.4. Modern and Contemporary Periods

3.4. The Impact of the Second World War—Forests in the 20th and 21st Century

4. Discussion

4.1. Cultural Landscape

4.2. Japanese Forest Management Guidelines and Their Background

4.3. The Genealogy of Forest Aesthetics Transmitted from Germany to Japan

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. The Author of Sakuteiki

References

- Arbeitskreis Forstliche Landespflege. 1991. Waldlandschaftspflege: Hinweise und Empfehlungen für Gestaltung und Pflege des Waldes in der Landschaft. Landsberg: Eecomed Verlags-Gesellschaft. [Google Scholar]

- Cook, Walter, Jr., and Doris Wehlau. 2008. Forest Aesthetics. Durham, NC: Forest History Society. ISBN 100890300720. [Google Scholar]

- Daniel, Eltringham. 2022. Poetry & Commons: Postwar and Romantic Lyric in Times of Enclosure. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Fujimori, Takao. 2001. Ecological and Silvicultural Strategies for Sustainable Forest Management. Amsterdam: Elsevier. ISBN 9780080551517. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazdowicz, Dariusz J., and J. Wiśniewski. 2011. Estetyka lasu (Aesthetics of Forest). Gołuchów: Ośrodek Kultury Leśnej w Gołuchowie. [Google Scholar]

- Gwiazdowicz, Dariusz J., and Tadeusz Janicki. 2024. Human and nature: Between destruction and creation. Studia Historiae Oeconomicae 42: 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hida, N. 2023. “Sakuteiki” as the origin of Japanese garden. Journal of Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture 87: 112–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hori, Shigeru, and Yoshio Yoshida. 2017. Forest Landscape Creation. Tokyo: Association of Forest Planning Publisher, ISBN 4889652485. [Google Scholar]

- Iijima, Hayato, Junco Nagata, Ayako Izuno, Kentaro Uchiyama, Nobuhiro Akashi, Daisuke Fujiki, and Takeo Kuriyama. 2023. Current sika deer adequate population size is near to reaching its historically highest level in the Japanese archipelago by release from hunting rather than climate change and top predator extinction. The Holocene 33: 718–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Japan Forestry Investigation Committee (J-FIC). 1997. Comprehensive chronology-The History of Japan’s Forests, Trees, and People. Tokyo: Japan Forestry Investigation Committee. ISBN 978-4-88965-091-4. [Google Scholar]

- Jones, Michael. 2003. The concept of cultural landscape: Discourse and narratives. In Landscape Interfaces; Cultural Heritage in Changing Landscapes. Edited by Hannes Palang and Gary Fry. Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, pp. 21–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinda, Akihiro. 2020. History of Japan Through Landscapes. Tokyo: Iwanami-Publisher. ISBN 104004318386. [Google Scholar]

- Kira, Tatsuo. 1975. Primary Production of Forests. In Photosynthesis and Productivity in Different Environments. Edited by John Philip Cooper. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 5–49. ISBN 9780521113427. [Google Scholar]

- Kitagawa, Hiroyuki, and Eiji Matsumoto. 1995. Climate implications of δ13C variations in a Japanese cedar (Cryptomeria japonica) during the last two millennia. Geophysical Research Letters 22: 2155–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Takayoshi. 2021. Journey to Forest Aesthetic in Quest of H. von Salisch Forest. Otsu: Kaisei-Sha Press. ISBN 10486099390X. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Takayoshi, and Tatsunori Koike. 2012. Forest history in Japan with a changing environment. Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej 11: 109–30. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Takayoshi, Sumie Kato, Yoshiya Shimamoto, Keiko Kitamura, Shoichi Kawano, Kumiaki Ueda, and Tetsuo Mikami. 1998. Mitochondrial DNA variation follows a geographic pattern in Japanese beech species. Botanica Acta 11: 87–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Takayoshi, Tatsunori Koike, and Hirofumi Ueda. 2022. Forest landscapes, scenery, views and metaphors. Hoppo Ringyo (Northern Forestry) 73: 179–82. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Takayoshi, Yuko Shimizu, and Seigo Ito. 2011. Development and application of forest aesthetics in Japan in relation to the ideas of H. Von Salisch. Studia i Materiały Ośrodka Kultury Leśnej 10: s47–s62. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Takayoshi, Yuko Shimizu, Taichi Ito, Masaki Shiba, and Seigo Ito. 2018. H. von Salisch’s Forest Aesthetics in Japanese. Otsu: Kaisei-Sha Press. ISBN 9784860999759/C3861. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Tatsunori. 2019. The generals and daimyō of the early Sengoku Period (Warring States period in medieval Japan) as seen in the “Magari-no-Jin”. Nihon Rekishi (Japan History) 851: 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Koike, Tatsunori, and Hirofumi Ueda. 2024. The development of “Sakuteiki” in the Edo period seen in the colophon (Oku-gaki). Journal Japanese Institute Landscape Architecture 17: 61–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Koike, Tatsunori, Takayoshi Koike, and Hirofumi Ueda. 2024. Forest Aesthetics as a basic idea for forest management from the perspectives of light quality, ecosystems, and sustainability in Japan. Studia Historiae Oeconomicae 42: 21–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Konda, Keiichi. 1934. Geschihte und Kritik der Groundfragen der Forstästetik. Research Bulletin of Hokkaido Imperials University Forests 9: 1–246. [Google Scholar]

- Kondo, Kimio. 1973. Environment and Landscape Theory (Kankyo-Shukei). Tokyo: Chikyu-Sha Publisher, ISBN 4804950206. [Google Scholar]

- Küster, Hansjörg. 2024. Different forms of civilizations and the development of woodlands: Systems of interactions. Studia Historiae Oeconomicae 42: 13–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitsui, Hideki. 2008. Japanese Beauty in Form: Japanese Design. Tokyo: NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) Publishing. ISBN 4140911239. [Google Scholar]

- Mizuno, S. 2015. Establishment of Satoyama-Environment and Resources in the Middle Ages. Tokyo: Yoshikawa Kobunkan. ISBN 13 978-4642082846. [Google Scholar]

- Niijima, Yoshinao, and Jyozo Murayama. 1918. Forest Aesthetic. Tokyo: Seibi-do Shoten, p. B0093EI4H0. [Google Scholar]

- Ogura, Juiichi. 1986. The Forests around Kyoto in the Period of Rakuchurakugaizu: A Study on the Description of “Rakugaizu”. Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History 11: 81–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, Juiichi. 2005. Human activities and vegetation change. Japan Landscape Ecology 9: 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ogura, Juiichi. 2017. The picture scroll “The Real Scenery of Higashiyama 36 Mountains” as evidence of late Edo period SATOYAMA landscapes around Kyoto. Journal Kyoto Seika University 52: 71–94. [Google Scholar]

- Okazaki, A. 1970. Forest Scenic Beauty and Recreation. Tokyo: Japan Forestry Investigation Committee (J-FIC), p. B000J932FM. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Kenkichi. 2009. Japanese Garden. Tokyo: Iwanami Paperback, No. 1177. ISBN 4004311772. [Google Scholar]

- Ono, Ryohei. 2005. The meanings and the intention of adoption of the term “Keikan” by Manabu Miyoshi. Journal of The Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture 71: 433–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Ooi, Nobuo. 2016. Vegetation history of Japan since the last glacial based on palynological data. Japanese Journal of Historical Botany 25: 1–101. [Google Scholar]

- Osumi, Katsuhiro, Hisashi Sugita, and Shigeto Ikeda. 2005. Ecological History of the Kitakami Mountain Landscape. Tokyo: Kokon-Shoin. ISBN 4-7722-1472-0. [Google Scholar]

- Sauer, Carl O. 1925. The Morphology of Landscape. In University of California Publications in Geography. Lanham: University of California Press, vol. 2, pp. 19–53. [Google Scholar]

- Shigemori, Chisao. 2010. Atlas of Japanese Garden. Tokyo: Natsume-Publisher. ISBN 978-4-8163-4673-6. [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu, Yuko, Seigo Ito, and Keizo Kawasaki. 2006. Development process from forest aesthetic to landscape management by the times before World War II. Journal of the Japanese Institute of Landscape Architecture 69: 395–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shinada, Yutaka. 2004. Human and Green Space-Interaction Between Them. Kanagawa: Tokai University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Solot, Michael. 1986. Carl Sauer and Cultural Evolution. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 76: 508–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stölb, Wilhelm. 2005. Waldästhetik—über Forstwirtschaft, Naturschutz und die Menschenseele. Kassel: Kassel Verlag. ISBN 103935638558. [Google Scholar]

- Takahara, Hikaru. 2007. Pollen-based reconstructions of past vegetation and climate. Low Temperature Science, Hokkaido University 65: 97–102. [Google Scholar]

- Takei, Jiro, and Marc P. Keane. 2008. Sakuteiki: Visions of the Japanese Garden (A Modern Translation of Japan’s Gardening). North Clarendon: Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 100804839689. [Google Scholar]

- Takeuchi, Kazuhiko, Robert D. Brown, Izumi Washitani, Atsushi Tsunekawa, and Makoto Yokohari, eds. 2003. SATOYAMA, the Traditional Rural Landscape of Japan. New York: Springer. ISBN 9784431000075. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, Kazuhiro. 1996. Introduction to Forest Management. Tsukuba: Japan Society of Forest Planning Press. [Google Scholar]

- Tatman, Conrad. 1989. The Green Archipelago: Forestry in Pre-Industrial Japan. Berkley: University of California Press. ISBN 9780520063129. [Google Scholar]

- Tatman, Conrad. 2007. Japan: An Environmental History (Environ History and Global Change). London: Bloomsbury Publishing. ISBN 9781786731524. [Google Scholar]

- The National Land Afforestation Promotion Organization (NLAPO). 1997. Chronological Table: The History of Japan’s Forests, Trees and People. Tokyo: The National Land Afforestation Promotion Organization. ISBN 978-4-88965-091-4. [Google Scholar]

- Tsutsui, Michio. 1995. Toward Forest Culture, Asahi Selection 529. Tokyo: Asahi publishing. ISBN 104022596295. [Google Scholar]

- Ueno, Mayumi, Hayato Iijima, Yoshihiro Inatomi, Saya Yamaguchi, Hino Takafumi, and Hiroyuki Uno. 2025. Spatial variation in local population dynamics of sika deer, Cervus nippon, through intensified management. The Journal of Wildlife Management 89: e70069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Unno, Satoshi. 2022. Japanese History of Forests, Trees and Architecture. Tokyo: Iwanami Paperback Pocket, ed. No. 1926. ISBN 104004319269. [Google Scholar]

- von Salisch, Heinrick. 1902. Fosrtästhetik Auf 2, Jena, Germany. Berlin: Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Wakui, Masayuki. 2006. The Japanese Mind as Seen Through the Landscape. Tokyo: NHK (Japan Broadcasting Corporation) Publishing. ISBN 104149105855. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Koike, T.; Ueda, H.; Koike, T. Landscape Change in Japan from the Perspective of Gardens and Forest Management. Histories 2025, 5, 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040060

Koike T, Ueda H, Koike T. Landscape Change in Japan from the Perspective of Gardens and Forest Management. Histories. 2025; 5(4):60. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040060

Chicago/Turabian StyleKoike, Tatsunori, Hirofumi Ueda, and Takayoshi Koike. 2025. "Landscape Change in Japan from the Perspective of Gardens and Forest Management" Histories 5, no. 4: 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040060

APA StyleKoike, T., Ueda, H., & Koike, T. (2025). Landscape Change in Japan from the Perspective of Gardens and Forest Management. Histories, 5(4), 60. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040060