Because I Could Stop for Death: Florida’s Death Row Prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s

Abstract

1. Introduction

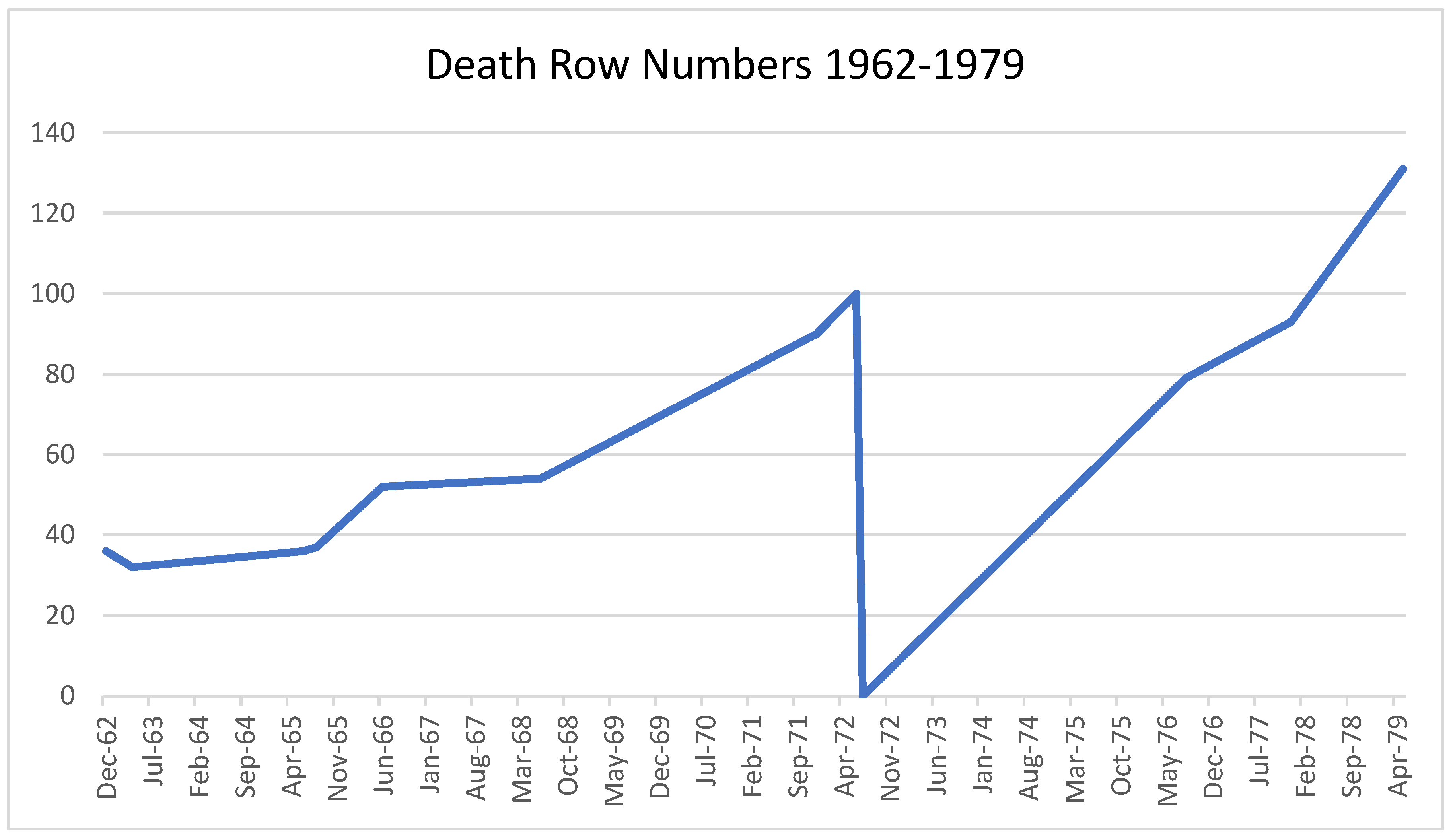

2. Investigating Capital Punishment in Pre-Furman Florida

3. Rethinking the Timeline of the Death Penalty Moratorium

4. Legal Challenges

5. Impact of the Moratoria on Death Row Prisoners

Between the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution in August 1964, the deployment of U.S. combat troops to Vietnam in March 1965, the Tet Offensive in early 1968, and Wilson’s letter, the war had become a brutal and bloody stalemate. African Americans were acutely aware that Black men were being drafted in disproportionate numbers (14.3 percent of all draftees 1965–1970) and casualty rates were rising. Black communities across the nation were deeply divided over the war. While many deeply patriotic draft-eligible Black men went willingly into the armed forces, others agreed with major civil rights leaders and Black self-defense groups that the war was immoral and should end, and supported draft resistance (Westheider 2007, pp. 20–37; Huebner 2008, pp. 171–206).“I was brought up in the State of Mississippi, and I still have a Family there; my mother, and Four younger Brothers…. I really think a man Should Serve his Country in time of war wherever it may be, but my Brother that’s nearly to go to the Army are nothing but a kid, and dont even know the facts of life itself, therefore I thought it worthy of Cause for me to write to you on this matter.”23

Aware that he might pose a flight risk, Wilson assured President Johnson, “I will plege myself to fight a double term or to the end of the Vietnam Conflict,” and commit to returning to death row “if you think I will go A.W.O.L.”26 Needless to say, Jimmie Wilson remained at Raiford. Even if his request had been considered seriously, his ability to pass essential military fitness tests would surely have been compromised by death row years of “virtual isolation and comparative inactivity and boredom.”27“Thus I feels morally obligated as well as obliged to submitt myself For duty in Vietnam or any other part of the war in the place of my Brother (Ernest M. Wilson) because what would in profit to send him off to war… Furthermore, I don’t think it will make sense to hold a man on death Row just to execute him, when he Could Serve his Country, as well as help his younger Brothers thats too young to help and take Care of theirselves and make it thru School.”25

While some prisoners painted or crafted objects, boredom was undoubtedly the main driver rather than unaffected enjoyment from a freely chosen leisure activity. An earlier news report described two African American death row men at Raiford playing cards, lying on their stomachs on the concrete floor, with their arms through the bars, and with the cards placed on a tea towel. Others played chess, did puzzles, listened to radios, or practiced push-ups in their cells. Some simply slept and smoked (Barry 1966).“Each cell is equipped with piped-in radio with earphones and the inmates are allowed to participate in their hobbies, i.e., reading, studying and educational materials, as long as those activities are activities that would not require material or objects that could be used in a manner which would be hazardous to the inmate, his fellow inmates or the correctional staff.”

6. Florida’s Death Row After Furman

Indeed, Section 2 of Proffitt’s last will and testament clearly states:“I regret to say that you have misconstrued the language in Mr. Proffitt’s Will. It is not his purpose to donate his body to science after death. However, it is his desire, prior to execution, to submit himself to various medical studies and research. Such study and research after his brain has been burned or distorted by a powerful electric current would not be practical, I believe.”41

There was extensive correspondence as to whether the state had a legal obligation to accede to Proffitt’s request, if there was any legal prohibition against it (according to the state Attorney General there was neither), and whether it was possible for a prisoner to donate his live body—as an “anatomical gift”—to any organization prior to death. It is not clear from surviving DOC correspondence how this issue was resolved, but Proffitt was not executed in 1976, and remained in prison under sentence of life imprisonment until his death from natural causes in February 2012.43“I have not believed myself completely normal in my mind. Alcohol, severe headaches and blackouts have bothered me. I did, for example, have episodes of blackout during the period July 9–10, 1973, during the approximate time Joel Medgebow met his death, and if I am permitted to go before a Board of Clemency…I will also agree to make myself available for a later full and complete psychiatric examination, to be conducted as designated psychiatrists may desire. Even though…I have no recollection of stabbing Joel Medgebow to death, I recognize that my chances of escaping electrocution are poor. I am truly regretful Mr. Medgebow died; and also, I desire to make a contribution to medical science to help determine from a study of my being now [so] mental abnormalities, if they exist, can be detected and successfully treated before tragedy strikes.”42

7. Conclusions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ACLU | American Civil Liberties Union |

| DOC | [Florida] Division of Corrections |

| LDF | National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, Legal Defense Fund |

| 1. | Copy of Petition for Writ of Mandamus, 22 November 1971, pp. 1–2, Record Group 103: Governor (1971–1979: Askew), Series 96: Executive Clemency Meeting Files, Box 8: Pardon Board—Special Project—Death Row Inmates, Florida State Library and Archives, Tallahassee, Florida, hereafter cited as FSLA. On Simon’s earlier requests for pardon board consideration of these seven prisoners, see Tobias Simon to Mrs. Alice S. Ragsdale, 2 November 1971, and 9 November 1971; Tobias Simon to The Honorable Members of the State Board of Pardons, 12 November 1971, FSLA S96/Box 8. Of the 90 prisoners on Florida’s death row in December 1971, 26 had been sentenced for rape and all were African American. |

| 2. | Tobias Simon to Honorable Members of the State Board of Pardons, 5 October 1971, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 3. | See individual clemency applications, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 4. | Copy of Petition for Writ of Mandamus, 22 November 1971, p. 3, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 5. | Minutes, Pardon Board Meeting, 16 December 1971, p. 23, FSLA S96/Box 5. |

| 6. | Memorandum, B. R. Patterson to Mr. Damon O. Holmes, 3 December 1971, pp. 1–2, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 7. | Tobias Simon to Hon. Reubin O’D Askew, 30 November 1971, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 8. | I have used “moratorium” or “moratoria” as an umbrella term for the different variations of death penalty suspension in Florida in the 1960s and 1970s throughout this article even though the term is more appropriate for a period of death penalty suspension or non-use that originiates with an executive or legislative decision rather than a judicial one. |

| 9. | See copies of Death Row rosters in FSLA S756 [Farris Bryant Correspondence, 1961–1965]/Box 63. |

| 10. | H. G. Cochran, Jr., to Honorable Farris Bryant, 10 April 1961, FSLA S756/Box 62. |

| 11. | Herbert E. Wilder to Governor Farris Bryant, 4 May 1964; Governor to Mr Herbert E. Wilder, 12 May 1964, FSLA S756/Box 64. |

| 12. | Louie L. Wainwright to Hon Ed H. Price Jr, 15 May 1964, S756/Box 64: “I would like to direct the Commission’s attention to the fact that since Earl Leach and Joe Smith were executed for killing another inmate on September 24, 1962, no further killings have occurred in any of the institutions.” |

| 13. | Several cases were highlighted in governors’ correspondence files, especially during 1970–1971. See for example, Order Denying Motion for New Trial and Recommending Commutation of Sentence, 23 January 1970, pp. 1, 2, and 5, S96/Box 8, from Circuit Judge A. H. Lane, Bartow, Polk County regarding Albert Bone Thompson. Thompson and two co-defendants were indicted for rape, of one victim, but tried separately before Lane, with the same evidence presented by different state attorneys, and resulting in sentences of death, 30 years imprisonment, and acquittal, respectively. See also Robert S. Hewitt to State Board of Pardons, 22 October 1971, S96/Box 8, regarding another gang rape case and disparate sentencing. |

| 14. | See for example, Craig v. State of Florida, 1967, in Capital Punishment; Discriminatory Death Penalty Law-Florida, 1959, American Civil Liberties Union Papers, 1912–1990, MS Years of Expansion, 1950–1990: Series 4: Legal Case Files, 1933–1990, Box 1317, Item 130, digitized from Mudd Library, Princeton University. |

| 15. | “On voter protests, see for example, Governor to Mrs Justine V. Prince, 4 May 1965, FSLA S131 [Haydon Burns Correspondence, 1965–1967]/Box 8. |

| 16. | The 36 death row prisoners were seven white males and 29 African American men. Most were lower-class men in their 20s and 30s. Of the men on death row: nine had arrived in 1960 (including three convicted of the same crime), six in 1961, five in 1962, four in 1963, eight in 1964 (including three for the same rape conviction), and two in 1965. The most recent arrival was 66-year-old Wallace Pleas in March 1965 from Leon County, convicted of murdering his wife. The longest death row inhabitant was 22-year old Dennis Whitney, a white male convicted of first-degree murder in Dade County in June 1960. He had shot three gas station attendants near Miami but was being sought in connection with at least three other murders in California and Arizona. The Dade county circuit judge who sentenced Whitney told the pardon board in December 1961, “Law enforcement in Florida would receive a severe setback if the death sentence of Dennis M. Whitney were commuted. This state has probably never had a more vicious wholesale killer and no consideration should be given to him for a commutation of death sentence.” Whitney’s application for commutation was denied but he was granted stays of execution in March and May 1964. See Report on Death Cases, 1965, S131/Box 16; Whitney v. State 132 So.2d 599 (1961). |

| 17. | For example, on Jefferson County Jail, see Memo from James E. Rozzelle to Louie L. Wainwright, 17 March 1967; Memo from Jack B. Straubing (Administrative Assistant in the Division of Corrections) to Mr. Louie L. Wainwright, 17 March 1967, FSLA S923/Box 58. Worse was to come. In December 1967, the U.S. Supreme Court described as “a shocking display of barbarism” the treatment given to Bennie Brooks, convicted of participating in a riot at Raiford in May 1965, after he and several others were held in sweatbox type conditions for two weeks. Brooks claimed that he was forced to confess to rioting. The Court reversed his riot conviction and the additional sentence of nine years. Brooks v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413, 416 (1967). |

| 18. | Governor to Honorable Earl Faircloth, 13 February 1967, FSLA S923/Box 58. After a case had gone through the appellate system, and the pardon board had reviewed it and denied commutation, a further series of checks were undertaken prior to a governor signing the warrant, i.e., each case was subject to a “legal sufficiency check” by the Attorney General. |

| 19. | “Status of Death Cases Involving Following Individuals On Death Row, Compiled February 22, 1967,” FSLA S923/Box 58. |

| 20. | Senator Jerry Thomas of Palm Beach County had already written to Kirk calling for an investigation by the Florida Sheriff’s Bureau to address a potential “gross miscarriage of justice” and for the governor to intervene in this “case which is attracting national attention and one which stands as a blemish on the courts of Florida.” See Jerry Thomas to The Honorable Claude Kirk, 8 February 1967, FSLA S923/Box 58. In March 1972, Pitts and Lee were re-tried in Marianna in another deeply problematic trial, and found guilty of first-degree murder a second time, and again sentenced to death. They were freed only after Governor Askew and a handful of Cabinet members voted to pardon on the grounds that both men were innocent of the murders for which they had been convicted. |

| 21. | H. G. Cochran, Jr., to Mr. Harold R. Tyler, Jr [Assistant Attorney General, Civil Rights Division, U.S. Department of Justice], 3 February 1961, p. 1, FSLA S756/Box 62. |

| 22. | See Memorandum of 21 June 1968, Roy L. Allen to Senator Adams, Subject: Complaint by Tobias Simon, Esquire, regarding inmates under death sentence at Florida State Prison,” pp. 2–5, FSLA S923 [Claude R. Kirk Official Correspondence]/Box 60. |

| 23. | Jimmie Wilson #A003253 to Governor John Bell William, 3 May 1968, pp. 1–2, FSLA S923/Box 60. |

| 24. | Jimmie Wilson #A003253 to Governor John Bell William, 3 May 1968, p. 3, FSLA S923/Box 60. |

| 25. | Jimmie Wilson #A003253 to Governor John Bell William, 3 May 1968, pp. 1–2, 5, FSLA S923/Box 60. |

| 26. | Jimmie Wilson, #A003253 to President Lyndon B. Johnson, 7 May 1968, p. 2, FSLA S923/Box 60. |

| 27. | Emmett S. Roberts of Health and Rehabilitative Services to Honorable Louie L. Wainwright, 14 December 1971, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 28. | Secretary of State Tom Adams to Honorable Doyle Conner, 25 June 1968; Memorandum of 21 June 1968, Roy L. Allen to Senator Adams, Subject: Complaint by Tobias Simon, Esquire, regarding inmates under death sentence at Florida State Prison,” p. 1; Governor to Mr. Louie L. Wainwright, 21 June 1968, FSLA S923/Box 60. By June 1968, Dennis Whitney was the longest serving death row prisoner, at eight years, while James Richardson, convicted of first-degree murder, had been on R wing for two days (Raum 1968, p. 6). |

| 29. | Memo from Gerald Mager to Governor Kirk, Subject: Investigation by Secretary of State of Death Row, 21 June 1968; Memorandum of 21 June 1968, Roy L. Allen to Senator Adams, Subject: Complaint by Tobias Simon, Esquire, regarding inmates under death sentence at Florida State Prison, pp. 3–4, FSLA S923/Box 60. Cirack had been convicted of first-degree murder in Titusville in March 1966. One of his co-conspirators was given a life sentence and the other avoided capture (Marsh 1972). |

| 30. | Memo from Gerald Mager to Governor Kirk, Subject: Investigation by Secretary of State of Death Row, 21 June 1968, FSLA S923/Box 60. |

| 31. | See Note 30 above. |

| 32. | Florida Governor Reubin Askew inspecting “death row” at Raiford prison. 23 January 1971. State Archives of Florida, Florida Memory: https://www.floridamemory.com/items/show/19249, accessed on 21 March 2025. |

| 33. | Emmett S. Roberts of Health and Rehabilitative Services to Honorable Louie L. Wainwright, December 14, 1971, FSLA S96/Box 8; Minutes, Pardon Board Meeting, 16 December 1971, pp. 23–24, FSLA S96/Box 5. Months earlier, when he took office, Askew had declared he would sign no death warrants. |

| 34. | Memo from Assistant General Counsel, B. R. Paterson to Mr. Damon O. Holmes, 3 December 1971, pp. 1–3, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 35. | Prison administrators, correctional officers, and other prisoners also cited security concerns and prisoner violence in their opposition to LWOP during post-Furman hearings (Seeds 2018, pp. 185–6). |

| 36. | Tobias Simon to Honorable Reubin O’D Askew, 30 November 1971, pp. 1–2, FSLA S96/Box 8. Simon pointedly told Askew: “In July, 1960, Jerry Chatman, an indigent de facto illiterate black man living in Lake County, Florida, under the rule of law imposed by Sheriff McCall, was convicted of the crime of rape against a white woman. You will not be surprised to learn further than the jury declined to recommend mercy and the sentence of death was automatically imposed.” Chatman was convicted on the basis of a forced confession, the illegal seizure of his clothing, and problematic footcast evidence. Death warrants were issued in August 1962 and April 1964, a stay of execution granted April 1964 as the appeal was heading to the U.S. Supreme Court in August 1964. See Chatman’s death penalty file in Askew files- Pardon Board—Special Project—Death Row Inmates, FSLA S96/Box 8. |

| 37. | Under the Donaldson v. Sack, 265 So. 2d 499, 505 (Fla. 1972) ruling, there was no death penalty in Florida. Under Anderson v. State, 267 So.2d 8 (Fla. 1972), forty death row prisoners whose appeals were still pending in the state supreme court were resentenced, and sixty prisoners who had no appeals pending were resentenced under In re Baker, 267 So.2d 331 (Fla. 1972). Ehrhardt et al. note that the men originally convicted of capital rape before 1972 were eligible to “file a motion with the trial court for mitigation of sentence from life to a term of years” (Ehrhardt et al. 1973, p. 11). |

| 38. | [Seven page] Petition for Redress, to the Honorable Governor of the State of Florida from the Inmates on Death Row at the Florida State Prison, no date, circa Dec 1975; Florida Department of Offender Rehabilitation Interoffice Memorandum, from Suzi Wilson [Information Director] to Louie L. Wainwright, 25 October 1976, Re: Media Access to Death Row, Florida State Prison, Starke. |

| 39. | Lewis identified 96 Florida death row prisoners in mid-1977; 60 percent were white and 40 percent were Black. Of the 98 Furman-commuted prisoners in 1972, two-thirds were Black and one-third white (Lewis 1979, p. 96). |

| 40. | While burglarizing a private home in Hillsborough County in July 1973, a drunk Proffitt attacked the sleeping homeowners. He fatally stabbed high-school wrestling coach Joel Medgebow in the chest with a butcher knife from the kitchen and seriously injured his wife. See Proffitt v. Florida 428 U.S. 242 (1976). |

| 41. | Memo from J. A. Anderson, Administrative Assistant, to Ramon Gray, Regional Director [State of Florida, Department of Offender Rehabilitation], 18 January 1977; Memo from Ramon L. Gray to John A. Anderson, Administrative Assistant, FSP, Re: Death Row Inmate Charles Proffitt, 27 January 1977; Letter from Jack O. Johnson, Public Defender, to Earl H. Archer III, Esquire, 30 December 1976; Letter from Earl H. Archer, III, to Mr. John Anderson, Florida State Prison, Re: Charles Proffitt, 10 January 1977, FSLA S96/Box 9. |

| 42. | Copy of Last Will and Testament of Charles William Proffitt, 27 November 1976, emphasis added, FSLA S96/Box 9. |

| 43. | The U.S. 11th Circuit Court of Appeals in Atlanta ordered a new sentencing hearing for Proffitt in 1982, and a Florida judge subsequently resentenced him to death, but he again appealed that decision to the state supreme court, arguing that his crime was not heinous enough to warrant the death penalty. Justices voted 6-1 in his favor. |

| 44. | Memorandum from Eleanor Mitchell to Governor Askew, 16 December 1977, S96/Box 9. |

References

Primary Sources

1958. He Sits in Death Row: ‘How Did I Go Wrong?’ Miami Herald, November 16.1960. Christmas on Death Row Is $2 Gift. Orlando Sentinel, December 19.1965. Reddick: Back To Raiford. St. Petersburg Times, January 23.1965. Death Penalty for Rape Draws Burns Opposition: He May Refuse to Sign Warrants. St. Petersburg Times, March 1.1965. Burns Stalls Death Penalty for Rape. Miami Herald, March 1.1971. Convict Courts Execution Stay. Fort Lauderdale News, February 14.1972. Court Spares 600; 4 Justices Named by Nixon All Dissent in Historical Decision. New York Times, June 30.1975. Hunger Strike Participants Drop Out. St. Petersburg Times, October 26.1975. Hunger Strike Ends. Pensacola News Journal, October 29.1975. Death Row Inmates May Resume Strike. Fort Myers News-Press, November 12.1976. Death Laws Are Legal, Court Rules. Fort Lauderdale News, July 2.1976. On Death Row: All I Have Left Now Is Prayer. Miami Herald, July 4.1976. Executions-Shevin Takes First Step. Miami Herald-Florida Report, July 15.1976. Florida Ready to Proceed. New York Times, October 5.2007. Retiring to a Florida Prison. The Observer News, February 8.Adderly v. Wainwright, 272 F. Supp. 530 (M.D. Fla. 1967).Anderson v. State, 267 So.2d 8 (Fla. 1972).Brooks v. Florida, 389 U.S. 413, 416 (1967).Donaldson v. Sack, 265 So. 2d 499, 505 (Fla. 1972).Furman v. Georgia 408 U.S. 238 (1972).Gregg v. Georgia 428 U.S. 153 (1976).In re Baker, 267 So.2d 331 (Fla. 1972).Proffitt v. Florida 428 U.S. 242 (1976).Ralph v. Warden 438 F.2d 786 (4th Cir. 1970).Secondary Sources

- Arkin, Steven D. 1980. Discrimination and Arbitrariness in Capital Punishment: An Analysis of Post-Furman Murder Cases in Dade County, Florida, 1973–1976. Stanford Law Review 33: 75–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banner, Stuart. 2002. The Death Penalty: An American History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Barry, Bill. 1966. Life on Death Row in Raiford Prison. Miami News, June 19. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, Abel A. 2000. Keeping the Faith: Race, Politics, and Social Development in Jacksonville, Florida, 1940–1970. Westport: Praeger. [Google Scholar]

- Blue, Ethan. 2011. The culture of the condemned: Pastoral execution and life on death row in the 1930s. Law, Culture and the Humanities 9: 114–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bryant, Nathaniel Heggins. 2019. On Frivolity and Contempt: The Reception of Caryl Chessman’s Prisoner Litigation. Law and Literature 31: 49–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campbell, James. 2017. Death Row Resistance, Politics and Capital Punishment in 1970s Jamaica. Crime, Histoire et Sociétés/Crime, History & Societies 21: 54–78. [Google Scholar]

- Christianson, Scott. 2010. The Last Gasp: The Rise and Fall of the American Gas Chamber. Berkeley: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Drane, Hank. 1965. ‘Every Appeal Is Utilized’ To Save Condemned Man. Fort Lauderdale News, August 1. [Google Scholar]

- Dyckman, Martin A. 2006. Floridian of His Century: The Courage of Governor LeRoy Collins. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Dyckman, Martin A. 2011. Reubin O’D Askew and the Golden Age of Florida Politics. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, Charles, and L. Harold Levinson. 1973. Florida’s Legislative Response to Furman: An Exercise in Futility. Journal of Criminal Law & Criminology 64: 10–21. [Google Scholar]

- Ehrhardt, Charles W., Phillip A. Hubbart, L. Harold Levinson, and William McKinley Smiley. 1973. The Aftermath of Furman: The Florida Experience. Journal of Criminal Law and Criminology 64: 2–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federman, Cary, and Dave Holmes. 2005. Breaking Bodies Into Pieces: Time, Torture and Bio-Power. Critical Criminology 13: 327–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzpatrick, Ben. 1964. Some Things You Didn’t Know About the Death Penalty. St. Petersburg Times Magazine, June 28, 11F. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Death Penalty Commission Report. 1965. Report of the Special Commission for The Study of Abolition of Death Penalty in Capital Cases, 1963–1965. Tallahassee: State Printers. [Google Scholar]

- Florida Department of Corrections, Execution List. 1924–1964. Available online: https://www.fdc.myflorida.com/institutions/death-row (accessed on 9 October 2025).

- Foerster, Barrett. 2012. Rape, Race, and Injustice: Documenting and Challenging Death Penalty Cases in the Civil Rights Era. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press. [Google Scholar]

- Franklin, Sekou M. 2010. The New South’s Abolitionist Governor: Frank E. Clement’s Attempt to Abolish the Death Penalty. In Tennessee’s New Abolitionists: The Fight to End the Death Penalty in the Volunteer State. Edited by Amy L. Sayward and Margaret Vandiver. Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, pp. 43–75. [Google Scholar]

- Freedman, Estelle B. 2013. Redefining Rape: Sexual Violence in the Era of Suffrage and Segregation. Cambridge and London: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Friedman, Lawrence M. 1993. Crime and Punishment in American History. New York: Basic Books. [Google Scholar]

- Garland, David. 2012. Peculiar Institution: America’s Death Penalty in an Age of Abolition. New York: Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gray, Emily. 2019. Decades in Death’s Twilight: Cruel and Unusual Punishment on Texas’s Death Row. New Criminal Law Review 22: 140–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamm, Theodore. 2001. Rebel and a Cause: Caryl Chessman and the Politics of the Death Penalty in Postwar California, 1948–1974. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press. [Google Scholar]

- Heinberg, Jerome L. 1966. A Study of Attitudes Toward Capital Punishment Among Legislators, Custodial Officers, and Prison Inmates. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Hubbart, Phillip A. 2023. From Death Row to Freedom: The Struggle for Racial Justice in the Pitts-Lee Case. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Huebner, Andrew J. 2008. The Warrior Image: Soldiers in American Culture from the Second World War to the Vietnam Era. Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, Anna. 2023. Declining Competency: Protecting Defendants With Worsening Mental Illness on Death Row from the Death Penalty. Boston College Law Review 64: 1723–61. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Robert. 2019. Condemned to Die: Life Under Sentence of Death, 2nd ed. New York and London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Johnson, Robert, and Jacqueline Lantsman. 2021. Death Row Narratives: A Qualitative Analysis of Mental Health Issues Found in Death Row Inmate Blog Entries. The Prison Journal 101: 147–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kerr, James. 1971. Death Row: Walking The Last Mile for Seven Years. Fort Lauderdale News, February 14. [Google Scholar]

- King, Gilbert. 2012. Devil in the Grove: Thurgood Marshall, the Groveland Boys, and the Dawn of a New America. New York: Harper Perennial. [Google Scholar]

- Kotch, Seth. 2019. Lethal State: A History of the Death Penalty in North Carolina. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, Steven F. 2003. Civil Rights Crossroads: Nation, Community, and the Black Freedom Struggle. Lexington: University Press of Kentucky. [Google Scholar]

- Lawson, Steven F., David R. Colburn, and Darryl Paulson. 1986. Groveland: Florida’s Little Scottsboro. Florida Historical Quarterly 65: 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, Peter W. 1979. Killing the Killers: A Post-Furman Profile of Florida’s Condemned: A Personal Account. Crime and Delinquency 25: 200–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewis, Peter W., Henry W. Mannie, Harry E. Allen, and Harold J. Vetter. 1979. A Post-Furman Profile of Florida’s Condemned—A Question of Discrimination in Terms of the Race of the Victim and a Comment on Spenkelink v. Wainwright. Stetson Law Review 9: 1–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marquart, James W., and Jonathan R. Sorensen. 1988. Institutional and Post release Behavior of Furman-Commuted Inmates in Texas. Criminology 26: 677–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marquart, James W., and Jonathan R. Sorensen. 1989. A National Study of the Furman-Commuted Inmates: Assessing the Threat to Society from Capital Offenders. Loyola of Los Angeles Law Review 23: 5–28. [Google Scholar]

- Marsh, Sandra Earley. 1972. Titusville Con: Want to Get out, And Get Married. Florida Today, June 30. [Google Scholar]

- McGuire, Danielle L. 2004. It Was like All of Us Had Been Raped: Sexual Violence, Community Mobilization, and the African American Freedom Struggle. Journal of American History 91: 906–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGuire, Danielle L. 2010. At the Dark End of the Street: Black Women, Rape, and Resistance: A New History of the Civil Rights Movement from Rosa Parks to the Rise of Black Power. New York: Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- Meltsner, Michael. 1973a. Litigating against the Death Penalty: The Strategy behind Furman. The Yale Law Journal 82: 1111–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltsner, Michael. 1973b. Cruel and Unusual: The Supreme Court and Capital Punishment. New York: Random House, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Gene. 1967a. Two Face Death for Murders I Committed. Miami Herald, February 5. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Gene. 1967b. Adams Tells Details of Killings in the Woods. Miami Herald, February 5. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Gene. 1967c. And May God Have Mercy on Your Soul. Miami Herald, February 6. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Gene. 1967d. Guilt Was Never in Question. Miami Herald, February 6. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Gene. 1975. Invitation to a Lynching. Garden City: Doubleday & Co. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Vivien. 2004. The last vestige of institutionalized sexism? Paternalism, Equal Rights and the Death Penalty in Twentieth and Twenty-First Century Sunbelt America: The Case for Florida. Journal of American Studies 38: 391–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, Vivien. 2017. It doesn’t take much evidence to convict a Negro: Capital punishment, race, and rape in mid-20th-century Florida. Crime, Histoire et Sociétés/Crime, History & Societies 21: 35–53. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Vivien. 2023. “I wanted satisfaction, and I got it”: Women, Homicide, and Capital Punishment in Jim Crow Florida. Crime, Histoire et Sociétés/Crime, History & Societies 27: 81–106. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, Vivien M. L. 2012. Hard Labor and Hard Time: Florida’s “Sunshine Prison” and Chain Gangs. Gainesville: University Press of Florida. [Google Scholar]

- Norris, Clarence, and Sybil D. Washington. 1979. The Last of the Scottsboro Boys: An Autobiography. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Oelsner, Lesley. 1976. Decision is 7-2; Punishment Is Ruled Acceptable, at Least in Murder Cases. New York Times, July 3. [Google Scholar]

- Perkinson, Robert. 2010. Texas Tough: The Rise of America’s Prison Empire. New York: Metropolitan Books. [Google Scholar]

- Poston, Ted. 1959. Negro Leader Urges End to Death Penalty in Fla. Assault Cases. New York Post, June 18. [Google Scholar]

- Radelet, Michael L. 1981. Racial Characteristics and the Imposition of the Death Penalty. American Sociological Review 46: 918–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raum, Tom. 1968. Of the 54 Who Wait…And Wait…For Death. The Tampa Times, June 15. [Google Scholar]

- Schoenfeld, Heather. 2018. Building the Prison State: Race and the Politics of Mass Incarceration. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. [Google Scholar]

- Seeds, Christopher. 2018. Disaggregating LWOP: Life Without Parole, Capital Punishment, and Mass Incarceration in Florida. Law & Society Review 52: 172–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Amy. 2008. Not Waiving but Drowning: The Anatomy of Death Row Syndrome and Volunteering for Execution. Boston University Public Interest Law Journal 17: 237–54. [Google Scholar]

- Steiker, Carol S., and Jordan M. Steiker. 2024. Capital Clemency in the Age of Constitutional Regulation: Reversing the Unwarranted Decline. Texas Law Review 102: 1449–72. [Google Scholar]

- Tartaro, Christine, and David Lester. 2016. Suicide on Death Row. Journal of Forensic Science 61: 1656–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tongue, Megan Elizabeth. 2015. Omnes Vulnerant, Postuma Necat; All the Hours Wound, the Last One Kills: The Lengthy Stay on Death Row in America. Missouri Law Review 80: 897–920. [Google Scholar]

- Vandiver, Margaret. 1983. Race, Clemency, and Executions in Florida, 1924–1966. Unpublished Master’s thesis, Florida State University, Tallahassee, FL, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Vandiver, Margaret. 1993. The Quality of Mercy: Race and Clemency in Florida Death Penalty Cases, 1924–1966. University of Richmond Law Review 27: 315–43. [Google Scholar]

- Vines, Brandon. 2022. Decency Comes Full Circle: The Constitutional Demand to End Permanent Solitary Confinement on Death Row. Columbia Journal of Law and Social Problems 55: 591–664. [Google Scholar]

- Vito, Gennaro F., and Deborah G. Wilson. 1988. Back from the Dead: Tracking the Progress of Kentucky’s Furman-Commuted Death Row Population. Justice Quarterly 5: 101–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Drehle, David. 2006. Among the Lowest of the Dead: Inside Death Row. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, Martin. 1965. Death Row: Last Resort For Florida’s Condemned. St. Petersburg Times, August 8. [Google Scholar]

- Waldron, Martin. 1972. Ruling Cheered on Florida Death Row. New York Times, June 30. [Google Scholar]

- Westheider, James E. 2007. The African American Experience in Vietnam: Brothers in Arms. Lanham: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe, Burton. 1969. Death Row Is Crowded with Waiting Men. Fort Lauderdale News, September 28. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Miller, V. Because I Could Stop for Death: Florida’s Death Row Prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s. Histories 2025, 5, 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040055

Miller V. Because I Could Stop for Death: Florida’s Death Row Prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s. Histories. 2025; 5(4):55. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040055

Chicago/Turabian StyleMiller, Vivien. 2025. "Because I Could Stop for Death: Florida’s Death Row Prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s" Histories 5, no. 4: 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040055

APA StyleMiller, V. (2025). Because I Could Stop for Death: Florida’s Death Row Prisoners in the 1960s and 1970s. Histories, 5(4), 55. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5040055