Abstract

The essay offers an expansive and multi-stratified investigation into the role of esoteric traditions within the development of Russian modernity, reframing occultism not as an eccentric deviation but as a foundational epistemological regime integral to Russia’s aesthetic, philosophical, and political evolution. By analyzing the arc from Petrine-era alchemical statecraft to the techno-theurgical aspirations of Russian Cosmism and the esoteric visual regimes of the avant-garde, this essay discloses the deep ontological entanglement between sacral knowledge and modernist radical experimentation. The work foregrounds figures such as Jacob Bruce, Wassily Kandinsky, and Kazimir Malevich, situating them within broader transnational currents of Hermeticism, Theosophy, and Rosicrucianism, while interrogating the role of occult infrastructures in both late-imperial and Soviet paradigms. Drawing on recent theoretical frameworks in the global history of esotericism and modernist studies, the long-read article elucidates the metaphysical substrata animating Russian Symbolism, Abstraction, Malevich’s non-Euclidian Suprematism and Moscow Conceptualism. This study contends that esotericism in Russia—far from marginal—served as a generative matrix for radical aesthetic innovation and ideological reconfiguration. It proposes a reconceptualization of Russian cultural history as a palimpsest of submerged sacral structures, where utopia and apocalypse, magic and technology, converge in a distinctively Russian cosmopoietic horizon. Ultimately, this essay reframes Russian and European occultism as an alternate technology of cognition and a performative semiotic universe shaping not only artistic modernism but also the very grammar of Russian historical imagination.

1. Prolegomena to the Study of Occultism and Modernism in Russia: A Comparative Perspective

The plurality of histories of Russian occultism, when approached through the prism of its intricate stratigraphy, reveal a dense palimpsest of esoteric traditions: Theosophy, Anthroposophy, Kabbalah, alchemical hermeneutics in their most sophisticated articulations, spiritualism, Russian cosmism, and a constellation of Gnostic systems (Gunn 2005; Carlson 1993; Ziolkowski 2013; Hanegraaff 1996; Bogomolov 1999; Ioffe 2008a, 2008b; Cerreta 2012; Bashilov 1992; Godwin 1994; Hanegraaff 2022). These interwoven strands contributed in decisive—if often subterranean—ways to the formulation of aesthetic, philosophical, and even political paradigms characteristic of Russian modernity. Far from being a mere compendium of fantastical or marginal beliefs, Russian occultism emerges as a coherent and dynamic epistemological system. The resurgence of esoteric thought in Russia at the fin-de-siècle must thus be understood not as a cultural anomaly but as a symptom of an ontological rupture: a desperate search for a restituted sacred cosmology amidst the fragmentation of inherited metaphysical frameworks (Hanegraaff et al. 2019; Holzhausen 2016; Johnson 2022; Kripal 2007).

In what follows, this essay seeks to lay a convincing scholarly groundwork for a sound and empirically substantiated argument that the esoteric and occult dimensions of Russian modern history must not be relegated to the margins as mere irrational aberrations or persecuted curiosities. Rather, they ought to be understood as constituting a powerful, coexisting, and at times dominant epistemological paradigm—one that functioned with a degree of cultural and intellectual authority comparable to the so-called rationalist or mainstream ideological frameworks. To support this claim, the article unfolds across several pivotal historical and aesthetic junctures. I begin by briefly inspecting the Petrine era’s “cultural esoteric renaissance”, a complex matrix in which Masonic thought, mystical natural philosophy, and alchemical models of transformation played a constitutive role in shaping the very ethos of early modern Russian statehood. From there, the analysis moves into the Symbolist-inflected esoteric ferment of the Silver Age, highlighting the proliferation of theosophical societies, spiritualist salons, and metaphysical poetics. It then proceeds to scrutinize the radical aesthetic metaphysics of the early twentieth-century avant-garde, with particular attention to the occult-inflected abstractionism of Kandinsky and the apophatic suprematism of Malevich. The concluding sections offer a theoretical reflection on the post-Soviet elaboration of these esoteric legacies in the major oeuvre of Moscow Conceptualism, focusing on key figures such as Ilya Kabakov, Andrei Monastyrsky, and Pavel Pepperstein, whose subversive praxis reanimates and transfigures the arcane symbolisms of earlier epochs into a new mode of aesthetic theurgy (see the series of my studies: Ioffe 2012, 2013, 2016, 2017, 2020, 2021a, 2021b, 2022, 2023, 2024).

For the purpose of this study, I envisage Unfinished Modernity as posed in my title, in the sense of Jürgen Habermas, who considered the modern project not as a completed historical formation, but rather as an ongoing epistemic and normative task, perennially deferred yet never relinquished. For Habermas, modernity was not merely a chronological epoch that succeeded the ancient régime, but a philosophical and cultural undertaking grounded in the Enlightenment’s self-reflexive rationality—a project tasked with emancipating reason from myth, subjectivity from dogma, and communicative praxis from coercive power. Yet in his canonical essay Modernity: An Incomplete Project, Habermas (1983); (Passerin D’Entreves and Benhabib 1996) rigorously defied the postmodernist temptation to abandon the normative aspirations of evolving modernity. Against the disillusionment that followed the epistemic and moral European catastrophes of the twentieth century—Auschwitz, GULAG, developing ecological collapse—he asserted that the core Enlightenment impulse, though compromised and mutilated by instrumental reason, still retains an emancipatory axis. The modern project, in his view, is ever non-complete because its internal logic—predicated on the differentiation of cultural value spheres (science, morality, and art)—has yet to be reconciled with lived experience. Rationalization has outpaced meaning; technocratic control has eclipsed ethical deliberation. Habermas, ever the dialectician, does not particularly mourn this incompletion as failure but elevates it as critical potential. Modernity’s “unfinishedness” is precisely what keeps it alive, open-ended, and self-corrective. It is this conceptual tension—between rationalization and emancipation, between system and lifeworld—that imbues modernity with a dynamic temporality, one that resists closure. Its telos is not the utopia of total knowledge or social harmony, but the ongoing labor of critique, communicative reason, and intersubjective understanding. The unfinished is not the broken; it is the unfinished because it is ever alive. Thus, to invoke Habermas is to reject both depressive relativism and blind progressivism in favor of an ethically alert, critically vigilant engagement with modernity as a horizon always receding, yet always beckoning. My essay deals with what I term Esoteric modernity of Russian cultural fashions from Petrine occult renaissance to the Moscow Conceptualist collectivity of underground resistance. A very pertinent question may arise about what made Russian culture such a fertile ground for occult tendencies, and how different Russian esotericism was from other cultures of the parallel times. Answering this complex question is rooted in the peculiar and “artificial” way Christianity found its path in the Slavic lands, letting the competing tendencies such as native religious remnants fluctuate in the background.

The true “occult” Modern(ist) “explosion” in late-imperial Russia and its immediate aftermath—spanning Symbolism, cosmism, anarcho-mysticism, and even nascent Bolshevism—proceeds from a shared impulse: the yearning for a renewed metaphysical architecture. Within this context, occultism functions as the cultural and spiritual nerve of what is often designated the Silver Age—here conceptualized as the Russian iteration of early modernism. It manifests in the radical reconfiguration of aesthetic principles within Symbolism and Futurism, and undergirds the emergence of a distinctive Russian religious philosophy and avant-garde theory of art. The work of art-theorists such as Pavel Florensky, Jeremiah Ioffe, and Alexander Gabrichevsky did not merely unfold alongside occult currents; rather, it was deeply embedded within them (Ioffe 2021a, 2021b; Wünsche 2018). Poets, visual artists, and philosophers did not simply appropriate isolated esoteric motifs—sphinxes, zodiacal constellations, pyramids, pendulums, spirals—but constructed entire aesthetic ontologies informed by hermetic logics. Structures such as the mandala, the word-as-object, synesthetic modalities, parapsychological inquiry, and mediumistic transmission were not peripheral curiosities, but central cognitive and structural matrices of Russian modernism (Ioffe and White 2012). The artistic text, in the spirit of Russian structuralist semiotics, becomes a ritual object; the poet, a theurgist; the word, a mechanism of ontological transfiguration. Even political phenomena—particularly the revolutionary imaginary—cannot be fully disentangled from these esoteric currents. The magic of power, the aesthetics of revolution, and the performative aura of Stalinist iconography all owe much to the occult legacies of the early 20th century. The tropes of suggestion, symbolic rigidity, sacred speech, and hieratic imagery that permeate Stalinist socialist realism are not merely rhetorical devices but are structurally homologous with the practices of Symbolist mysticism, Theosophical metaphysics, and spiritualist ritualism. In this optic, Stalin gains a peculiar status of an architect of mythopoeic space, and choreographer of sacralized public vision. Socialist realism, far from being a straightforward aesthetic of transparency or proletarian mimesis, begins to appear as some sort of an alchemical theater of ideological transmutation.

Crucially, Russian and subsequently Soviet occultisms must be situated within the broader framework of what Nyle Green, in his programmatic essay “The Global Occult” (Green 2015), has termed global occultism—a vast and protean transnational formation arising at the intersection of religious innovation, colonial entanglement, and technological acceleration. Green challenges the Eurocentric teleology of religious historiography by positing occultism not as a regressive or residual phenomenon, but as a constitutive mode of modernity itself. He argues that turn-of-the-century occultism must be approached as an active, productive religiosity—an infrastructure of perception, subjectivity, and symbolic capital that reconfigures the boundaries between East and West, science and magic, modernity and tradition. Central to this formulation is the concept of bicultural metaphysics: the emergence of hybridized spiritual forms arising from geographically and epistemologically dislocated zones of cultural production. In this light, occultism may be read as a “hidden history” of global modernity—an unofficial, often subterranean matrix that nonetheless shaped the symbolic economy of the modern age. The well-known Latin root of occultus (“hidden”) becomes not simply a descriptor but a methodological imperative: to uncover the latent religiosities born of techno-spiritual synthesis, wherein Eastern mysticisms conjoin with Western material infrastructures (Green 2015).

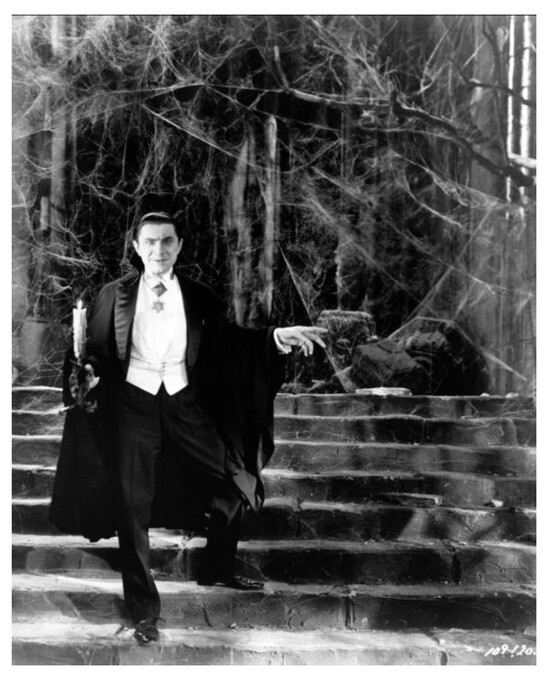

Such “new religious institutions” (to adopt Max Weber’s experimental terminology of creative religious entrepreneurship as a socially preferred practice favored by God) offered access to arcane knowledge via modern apparatuses: photographic technologies, telegraphy, psychophysiological experimentation, scientific catalogs, and psychoanalytic nomenclatures. In this frame, occultism does not necessarily oppose scientific discourse—it incorporates and recasts it. Magic is not asserted in defiance of science but articulated through its idioms and instruments. Occult practice borrows its method and mimics its authority. Spiritual entities are captured on photographic plates, spectral voices recorded via phonographs, yogic breathing rearticulated as biomechanics. In short, occultism is subsumed into the epistemological field of radical modernity (Talar 2009; Trompf 2019; Deconick and Adamson 2013; Partridge 2019; Ingman 2010; Ioffe 2008b; Janacek 2011; Johnston 2014; Lee 2019; Luck 2006; Magnússon 2018; MacIntosh 1997; Magee 2016; Maxwell-Stuart 2005; Mercier 1969; Moran 2016; Morrisson 2008; Otto 2019; Owen 2004). Global occultism reveals itself as a complex sociotechnical assemblage—simultaneously a religious movement, a media ecology, a commercial network, and a mechanism of subject-formation. Practices such as automatic writing and telepathy are inextricably bound to contemporaneous communication technologies and semantic innovations (e.g., telegraphy → telepathy). Literary works—most famously Dracula (Figure 1) by Bram Stoker—encapsulate and popularize these hybrid phenomena, weaving together technology, politics, and the supernatural into a unified cultural code.

Figure 1.

Bela Lugosi in Tod Browning’s “Dracula”, 1931. The story by Bram Stoker.

In aggregate, transgressive occultism at the fin-de-siècle should be reconceptualized as a multidimensional apparatus of creative modernity: a conduit between religion and science, empire and dissent, individual consciousness and global systems of symbolic production. It reflects not only the anxieties and aspirations of its age, but also the very mechanisms through which modernity articulated and sustained its epistemic authority (Cf. the vast field of information in Bauduin and Johnsson 2018; Birksted 2009; Bramble 2015; Clark 1999; Crasta and Follesa 2017; Edwards 2016; Faivre 2010; Fanger 1998, 2012; Forshaw 2017, 2024; Hanegraaff 2012; Hobson and Radford 2023; Iafrate 2019; Hunt 2003).

2. The Radical Modernization of the Occult in Russia: Petrine Cultural Esotericism

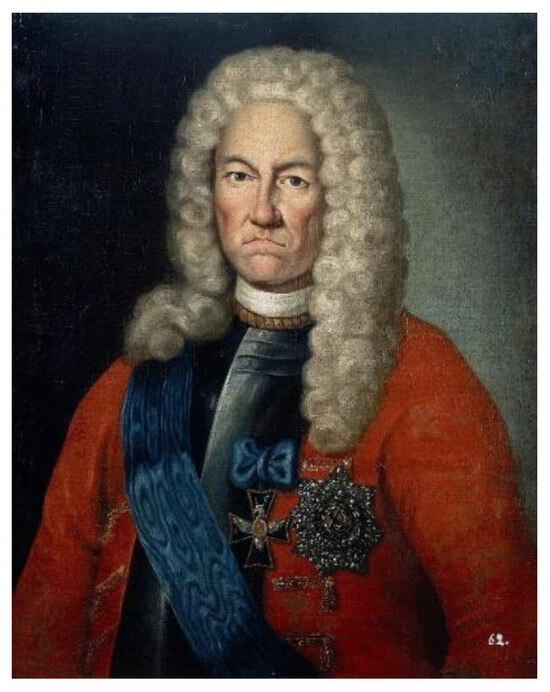

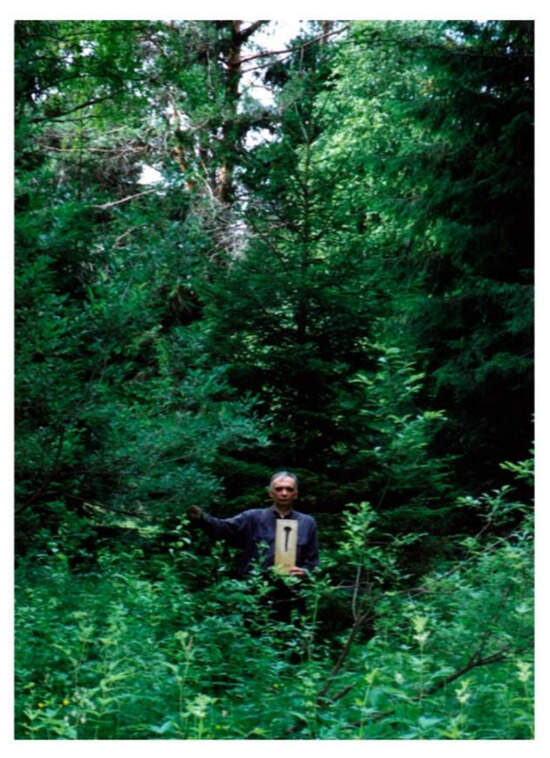

The history of the complex interaction between Western European esoteric traditions and Russian occult culture within the imperial capitals of Russia reveals a particularly intricate and layered dynamic. Thanks to the invaluable scholarship of Robert Collis, we now possess a much deeper understanding of the Petrine instauration as a sacral-esoteric project, entailing a hermetic reconfiguration of imperial power and culture. In his seminal monograph (The Petrine Instauration: Religion, Esotericism and Science at the Court of Peter the Great) (Collis 2012), Collis radically revises conventional narratives of Russian modernization, secularization, and Europeanization, approaching them instead through the lens of a hermetically oriented historiography. The central thesis of Collis’s work posits that at the court of Peter the Great, a large-scale esoteric-initiatory program unfolded—outwardly couched in the rhetoric of reform, yet fundamentally rooted in the symbolic matrices of Hermeticism, Kabbalah, and alchemy, often in deliberate tension with the rationalist doctrines of the Enlightenment. The Petrine instauration—a term drawn deliberately from the Baconian philosophical lexicon—thus appears not merely as a bureaucratic or administrative modernization of the state apparatus, but as a sacred project of cosmogonic and epistemological regeneration. Peter is not interpreted as a secular reformer in the spirit of Voltairean Enlightenment, but rather as a complex cultural figure—an “engineer of the apocalypse”, who combines the attributes of Solomon, Hermes Trismegistus, and the imperial architect of a new eon. In this esoteric schema, Jacob Bruce (Figure 2) assumes the role of a crucial mediator, a proponent of what may be described as “sacred technoscience”, bridging alchemy and imperial gnosis.

Figure 2.

Jacob Bruce (James Daniel Bruce = Yakov Wilimovich Bryus 1669–1735).

At the core of this metaphysical architecture stands the enigmatic persona of Jacob Bruce, one of Peter’s most trusted collaborators (Collis 2012; Khalturin et al. 2015; Faggionato 2005; Khil’chenko 2021; Kivelson 2013; Kondakov 2018; Leighton 1994; Mannherz 2012; Mikhailova 2018).

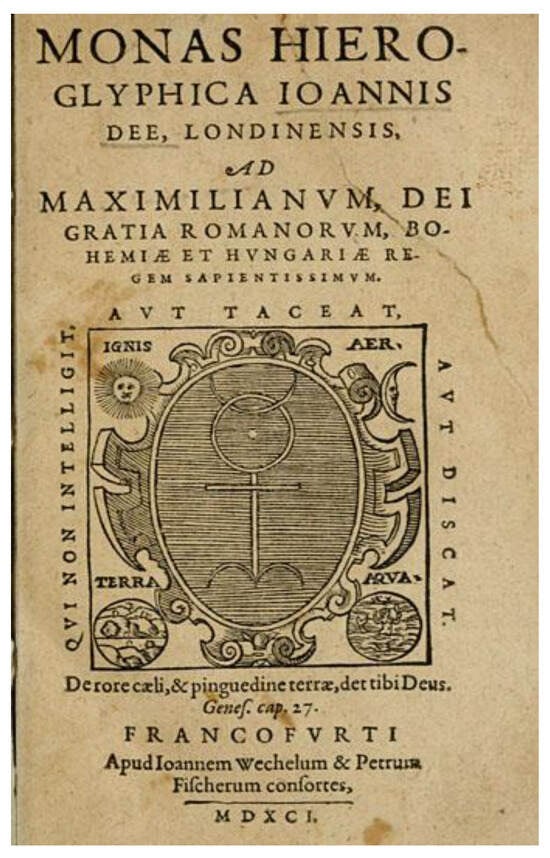

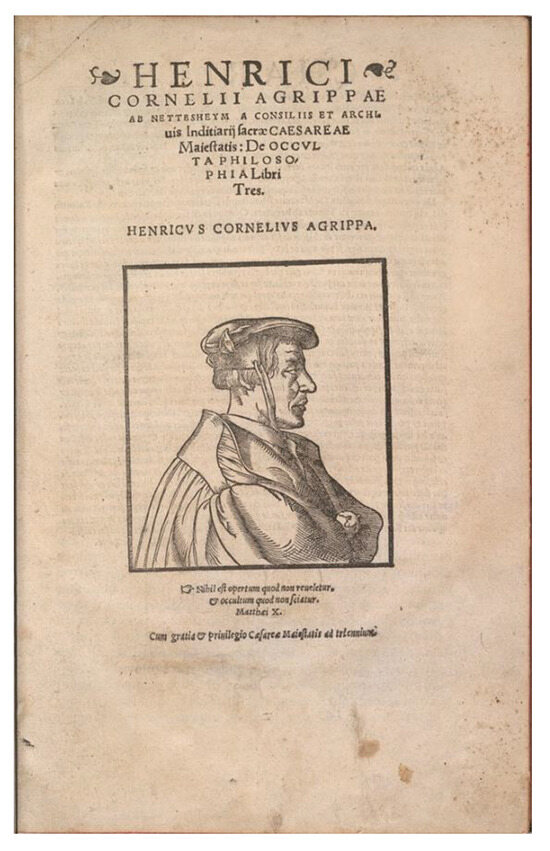

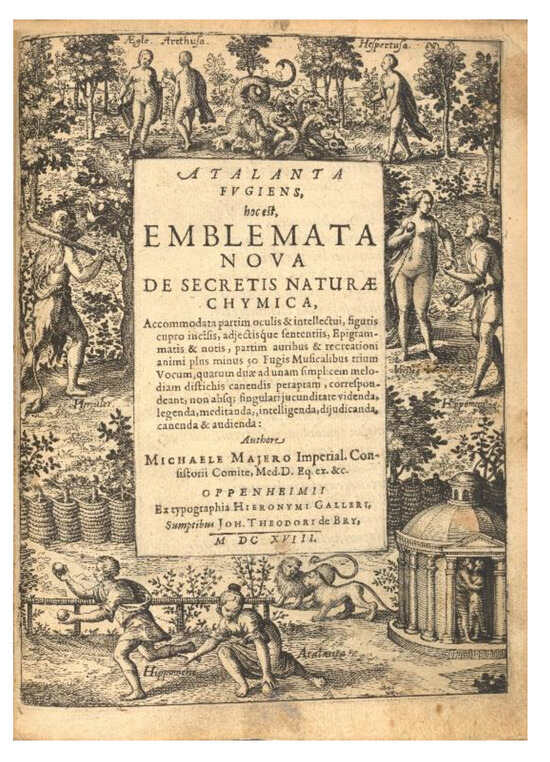

As Collis showcases, Bruce’s activities cannot be fully grasped without reference to the alchemical-Gnostic tradition. He is not merely an astronomer, cartographer, or political functionary, but rather a transmitter of transcendent knowledge, a custodian of initiatory epistemes, and a practitioner of sacred scientism in which cosmological observation is intrinsically bound to ritual transformation. Among Bruce’s contributions was his patronage of the so-called Bruce Calendars—astronomical and astrological almanacs saturated with planetary symbolism, cyclical cosmologies, and iconographic engravings (Collis 2012). Bruce is also reputed to have overseen clandestine alchemical experiments within the Apothecary Order, whose operations under his aegis straddled empirical medicine and esoteric ritual. His personal library—partially reconstructed by Collis from surviving archival registries—attests to his deep involvement in esoteric currents. Among the volumes listed are John Dee’s Monas Hieroglyphica, Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa’s De Occulta Philosophia (Figure 3 and Figure 4), Michael Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens, and multiple editions of Rosicrucian manifestos such as the Confessio Fraternitatis and the Chymische Hochzeit Christiani Rosenkreutz (Cf. Rabinovitch 2002; Radulović and Hess 2019; Sigrist 2005; Schmidt 2003; Spinks and Eichberger 2015; Surette and Tryphonopoulos 1996; Surette 1993; H. Urban 2016; Van den Broek 1998, 2013; Versluis 2004; Waddell 2021; Williams and Gunnoe 2002; Bogdan 2008; Wilson 2013; Zika 2003; Henderson 1987; Collin de Plancy 1863; Harari 2005).

Figure 3.

Monas Hieroglyphica.

Figure 4.

Agrippa, De Occulta Philosophia.

These were not collected as curiosities or for erudition alone; rather, they served as hermeneutic instruments for the symbolic reimagination of the empire itself. Of parallel significance is the figure of Robert Erskine, whose unique synthesis of medical alchemy situates the imperial body—both literally and metaphorically—as an alchemical vessel of state transmutation. Robert Erskine, Peter’s chief physician and director of Medical Chancellery, appears in Collis’s narrative as a key agent of corporeal and political metamorphosis. A Scottish-born physician trained at Leiden, Erskine imported to Petrine Russia a distinctly Paracelsian iatrochemical worldview, wherein health was conceptualized as the dynamic equilibrium of metaphysical fluids circulating between human physiology, the astral plane, and divine substance. Collis shows that Erskine supervised alchemical experiments aimed at isolating the primum ens—the primordial essence associated in Hermetic pharmacology with the originary spark of the cosmos. These experiments were conducted in close correspondence with European alchemists such as Rudolf Steiglin and Otto Tachenius (Collis 2012).

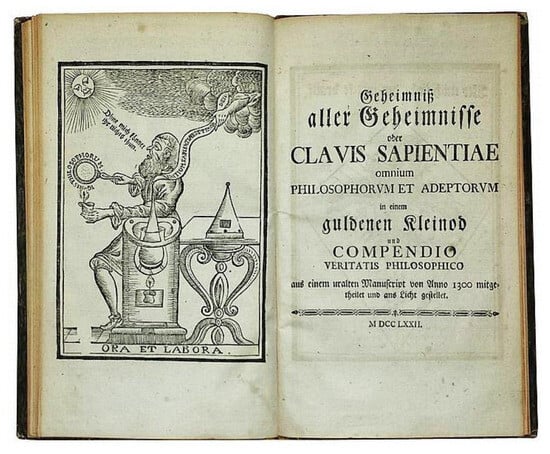

Notably, in 1714 Erskine commissioned a Latin manuscript from Halle entitled Clavis Hermeticae Sapientiae (Figure 5), attributed to the pseudo-Basilius Valentinus and devoted to the ritual distillation of metals.

Figure 5.

Clavis Hermeticae Sapientiae.

He also directed the translation of the sixteenth-century alchemical compendium Artis Auriferae from Latin into German, subsequently integrating fragments of the text into the educational curriculum of Petrine-era medical institutions. Thus, Peter’s own body became artistically implicated in a ritual of sacred therapy wherein alchemy emerged not as a peripheral pseudoscience but as the epistemological foundation of sovereign biopolitical control.

Peter the Great, as a subject of both local aspiration and transnational eschatological projection, was frequently imagined in Western Europe as a variant of the rex philosophorum within chiliastic and prophetic discourse. Collis devotes considerable attention to reconstructing the Western mythopoetic image of Peter as a messianic sovereign of the final age—a figure upon whom millenarian hopes for the apocatastatic restoration of humanity were projected. Of particular interest is a letter from Francis Lee, leader of the Philadelphian Society, addressed to the Pietists of Halle, in which Peter is hailed as “the gatekeeper of the millennial kingdom” and “the architect of the new Zion Grad” (Collis 2012). Prophetic formulae accumulated around the Russian tsar: sol regit omnem, nova arca Dei, dux sapientiae borealis. Philipp Jakob Spener, in several of his theological works, speculated that Russia might become the future site of the ecclesia spiritualis—a community where science, mysticism, and divine revelation would converge to generate the archetype of the New Adam.

One of these Petrine occult academies, or collegium lucis, was envisioned as being established in Russia—either in Moscow or in the nascent imperial capital of St. Petersburg—under the personal aegis of Peter the Great. Here, the spatial poetics and esoteric geography of St. Petersburg assume particular significance. In his most illuminating chapters, Collis develops an original interpretation of the architectural and urban symbolism of St. Petersburg as an artificial sacral chronotope—a metaphysical topography structured according to hermetic and Kabbalistic principles. Drawing on the concept of “mystical topography” (as theorized by Frances Yates and Keith Critchlow), Collis argues that the spatial design of the new imperial capital reflects the numerological and geometric ideals of the mundus geometricus—a cosmos ordered according to archetypal and mathematical laws. The axial organization of Nevsky Prospekt, the intersecting canal systems, and the geometrical rigidity of the urban plan are seen as concrete expressions of esoteric cosmography (Collis 2012).

Within this schema, the Peter and Paul Fortress, constructed in the form of a six-pointed star, is interpreted not merely as a military installation but as a temple of wisdom, its hexagram referring to the Seal of Solomon—a central symbol in alchemical and Rosicrucian visual culture (Khalturin et al. 2015; Faggionato 2005; Iafrate 2019). Similarly, the Kunstkamera—Russia’s first public museum and Peter’s personal intellectual project—is not simply a cabinet of curiosities, but a hermetic encyclopedia, an “archive of post-Noveauvian knowledge” synthesizing empirical specimens with mystical signification. The so-called “hermetic genesis” of the Russian Empire, as interpreted by Collis, challenges all the existing rationalist and positivist schemas of mainstream Petrine historiography. Peter the Great must be reimagined not merely as a secular modernizer, but as a transhistorical figure of alchemical synthesis: a monarch who conjoined the political will to power with the esoteric imagination of a sacred architect. In this reading, the instauration he enacted is not a “reform” in the narrow sense of rational administration, but a hermetic regeneration of the world—a total project of symbolic cosmopoiesis inscribed upon the body of the empire, the spatial order of the city, and the very figure of the sovereign himself.

The chronicle of essential transmutation and the alchemical-esoteric history of Peter the Great’s empire (1689–1725) occupies a particularly idiosyncratic place within the broader histories of Russian occultism that are under consideration in this essay. The period spanning from the final decades of the seventeenth century through the culmination of Peter’s reign in 1725 is marked not solely by administrative and military convulsive revolutions, but also by a subtle, yet powerful, hermetic auricization of power. During this epoch, alchemy—together with its epistemological counterparts: iatrochemistry, astromagic, Kabbalah, and naturophilosophy—enters into a productive, though largely subterranean, alliance with the institutions of Enlightenment and reform. The year 1689, marked both by Peter’s political ascendancy and what one may term a sacred conjunction, coincides with the intensification of Rosicrucian and Baconian discourses across Europe, particularly within English millenarian and German Pietist circles. This conjuncture set the occult horizon for the future instauration. Already at this early stage, deliveries of “natural books”—alchemical and astrological treatises including Latin editions of the Musaeum Hermeticum and the Speculum Sophicum Rhodo-Stauroticum—were documented through the Moscow embassy. Collis documents Peter’s interest in manuscripts concerning the Philosopher’s Stone, notably the Testamentum Morientis Philosophorum, attributed to Arnaldo di Villanova. It was in Holland that Peter acquired the earliest copies of hermetic treatises destined for the future imperial library. Among these was Chymia Philosophica (1697), a compendium including works by Michael Maier, Basil Valentine, and, significantly, Jacob Böhme—volumes that would later appear in the inventory of Jacob Bruce’s library (Figure 6 and Figure 7) (Collis 2012; Khalturin et al. 2015).

Figure 6.

Atalanta fugiens hoc est, Emblemata nova de secretis naturae chymica, 1618.

Figure 7.

Emblema XXI. De secretis Natura. Atalanta Fugiens, 1618.

By the early 1700s, alchemy had become, if not an official discipline, then at least a quasi-legitimate (para)science of the imperial court. Notably, the founding of the School of Mathematical and Navigational Sciences in Moscow in 1701 coincided with the establishment of the first state-run chemical laboratories.

The years 1706–1710 witnessed a further intensification of this esoteric representation of power, coinciding with the apogee of hermetic symbolism in the mid-1700s. In 1708, Peter commissioned the production of so-called “engravings of glory”—ceremonial prints bearing allegorical depictions of the tsar. Among these, a singularly significant image portraying Peter as the Sun surrounded by planets, echoing the astrological configurations found in the Renaissance esotericism of Ficino and Agrippa. The legend inscribed on the engraving reads: Petro Regi Philosophorum Lux Nova Borealis. Simultaneously, Peter’s victory medals began to incorporate overtly alchemical motifs: lions clutching vessels of mercury; glyphs denoting alchemical metals; allegories of transmutation, where an aged man clad in black (nigredo) is transformed into a crowned sovereign in gold (rubedo). Such iconography is not mere decoration; it constitutes a ritualized semiotics of power, enacting the sacred message through hermetic code.

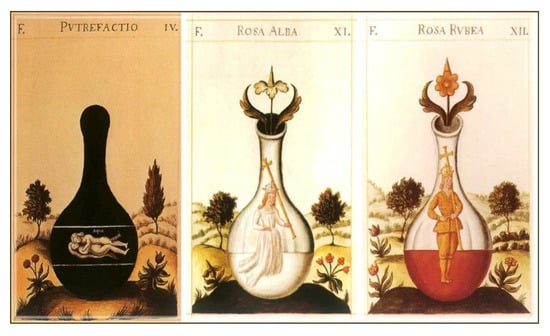

With the arrival of the 1720s, suggestive alchemical symbolism appears embedded even in the performative constitution of empire. The 1721 proclamation of the Russian Empire is an event suffused with esoteric significance. Peter received the titles “The Father of the Fatherland” and “Emperor of All Russia”, accompanied by the issuance of a new medal depicting a phoenix rising from the ashes, emblazoned with the motto Per Ignem ad Lucem (“Through Fire to Light”)—a formulation that nearly paraphrases the core maxim of alchemical philosophy. This could be read as the final gesture of sacred transmutation: the kingdom is recast as an empire through the purifying flame of hermetic renewal. The tsar’s final illness in 1724–1725 may likewise be interpreted as an initiatory rite. Anticipating his own death, Peter wrote to Erskine of “the fate of kings whose bodies decay, but whose spirits remain in substances.” Collis notes that the very form of Peter’s tomb evokes the image of an alchemical vessel—retorta mortis—within which the monarch’s body serves not as a corpse but as the symbolic matrix (Figure 8) of the final fixation of instauration: not decomposition, but transmutation into the metaphysical light of the philosophical Empire.

Figure 8.

Alchemical vessels. The three phases of the magnum opus: nigredo, albedo and rubedo. Pretiosissimum Donum Dei, by Georges Aurach, 1475.

One of the central axes of the discussed esoteric narrative as proposed by the current study is undoubtedly alchemy, which consistently functioned not merely as a proto-scientific technique for transmuting metals, but as a holistic philosophy of nature. In the shift from premodernity to modernity, alchemy transformed from a laboratory craft into a comprehensive metaphysics of matter—an ontological worldview interpreting the cosmos as an organic and symbolically saturated structure. This transformation brings it into direct alignment with the Hermetic tradition, Neoplatonic cosmology, and theosophical ontology. Special attention, in this regard, must be paid to the quintessential figures of Paracelsus, van Helmont, Jacob Böhme, Robert Fludd, John Dee, and many others too numerous to be listed here. Each contributed to the elaboration of an alchemical cosmogony in which physical transmutation was allegorically linked to divine creation and spiritual regeneration. For example, Böhme’s concept of the Ungrund (groundlessness of being) resonates with the primordial alchemical chaos, while his triad—Sauer, Süß, Bitter—parallels the alchemical trinity of sulfur, mercury, and salt. This conceptual shift from empirical procedure to metaphysical hermeneutics situates the metaphysics of matter at the core of late alchemical thought. Alchemy, in this cluster of meanings, becomes a counterpoint and companion to the emerging sciences of the New Age. While it creatively engages with discoveries in physics, medicine, and chemistry, it retains a symbolic and archaic lexicon. Alchemists studied astronomy, anatomy, and mechanical arts, yet interpreted these disciplines through the macrocosmic–microcosmic analogy (Von Martels 1990; Janacek 2011; Dupré et al. 2014; Patai 1994; Calvet 2018).

Hence, the paradox: alchemy is simultaneously an ancient science of elemental coexistence and a precursor to systemic theories of matter and energy. The central textual corpus of this tradition—including Splendor Solis, Mutus Liber, Maier’s Atalanta Fugiens, the Theatrum Chemicum, and the Rosicrucian manifestos Fama Fraternitatis and Confessio Fraternitatis—function not simply as doctrinal works but as initiatory architectures. In these texts, truth is not asserted propositionally but encoded in allegory, symbol, and mystery—demanding interpretative insight and spiritual intuition. A particularly vital trajectory in this constellation is the history of Russian Rosicrucianism, which represents a cultural transfer and localized adaptation of Western esoteric models. Via Masonic channels, beginning in the 1770s, Rosicrucian thought permeated Russian intellectual culture through the activity of the Brotherhood of the Golden and Rosy Cross. Moscow became a center of dissemination, with key figures such as Novikov, Schwartz, Gamalei, Labzin, and Lopukhin spearheading the movement. Yet Russian Rosicrucianism was far from a simplistic imitation. Rather, it underwent a deep process of cultural indigenization, in which alchemical concepts were reinterpreted through the prisms of Orthodox mysticism and Russian sentimentalism. For these thinkers, the quest was not so much the literal transmutation of base metals into gold, but the symbolic restoration of fallen humanity—the spiritual regeneration of Adam. Alchemy thus becomes a transgressive metaphor for Christian sanctification, a sacramental allegory of inner metamorphosis.

A central space within this interpretive register must be accorded to the study of the corpus of texts compiled within Russian Masonic and Rosicrucian lodges: treatises such as On the Philosopher’s Stone, On the Mystery of the Three Substances, On the Inner Man, along with translations of works such as Brandt’s On the Seven Stages of Inner Alchemy and the Latin pamphlet bearing the alchemical-mystical inscription Ex Deo nascimur, in Jesu morimur, per Spiritum Sanctum reviviscimus. These texts are marked by a distinctive synthesis of Kabbalistic cryptic vocabulary, Christian soteriology, and alchemical hidden symbolism—a fusion which reflects the aspiration to sacralize scientific inquiry and to return to a pre-rational, integrative vision of being. Remarkably, the Russian Rosicrucians developed an entire esoteric pedagogy. They founded clandestine academies in which initiates were systematically instructed in alchemical and hermetic disciplines. These educational endeavors drew not only on Latin and German sources but also upon original compilations, emblematic imagery, and chemical experiments reinterpreted through metaphysical frameworks. This initiative represented a deliberate effort to construct an ad hoc esoteric academy, conceived as an alternative to the institutionalized mechanisms of imperial science (MacIntosh 1997; Faggionato 2005; Dmitriev 2023; Khalturin 2015; Lanchidi 2021; Menzel 2012; Endel and Burmistrov 2004; Carlson 1993; Menzel et al. 2012; Khalturin et al. 2015; Burmistrov 2024).

Within the Russian context, unique conceptual idioms emerged—terms such as “philosophical salt”, “fire of nature”, “living silver”, “royal spirit”, and “inner vessel”—each of which encoded both chemical operations and anthropological dramas. The alchemical process was imagined as a spiritual odyssey: the soul’s passage from obscurity to illumination, from decomposition to resurrection. In this optic, the laboratory is reimagined as a temple, the retort becomes the Grail, and the desired product is no longer a substance but a radiant insight. Esotericism, in this formulation, functions as a cryptic epistemology—an effort to rethink the very foundations and modalities of human knowledge. It calls into question the linear-progressive model of scientific and cultural development in which esotericism is relegated to the status of some primitive residue. On the contrary, alchemy and Rosicrucianism should be seen as active and parallel participants in the processes of modernization—developing distinct forms of rationality, ethics, and cognition in which the sacred and the material, the symbolic and the practical, coalesce in an indivisible synthesis (Faggionato 2005; MacIntosh 1997).

This line of argumentation aligns organically with the intellectual framework of modern Western Esotericism Studies, as developed by scholars such as Antoine Faivre and Wouter Hanegraaff (Faivre 2010; Hanegraaff 2022). One may possibly consider situating Russian occult specifics within this broader metaphysical framework but also to reconstruct a localized, culturally specific variant of the tradition—formed under the unique epistemological and ideological conditions of Russian idiosyncratic culture. Indeed, it seems increasingly untenable to approach the cultural history of eighteenth- and nineteenth-century Russia—or, by extension, of Eastern Europe—without attending to the subterranean layers of esotericism. In this expanded perspective, alchemy no longer appears as a science of substances alone, but as a scientia coelestis—a celestial archeology deciphering the encrypted codes of a lost paradise. This comparative undertaking fits seamlessly into the growing body of international scholarship that, since the 1990s, has sought to discipline the study of esotericism as a legitimate and autonomous domain within the humanities (Asprem and Granholm 2013; Asprem 2021). While Faivre focused primarily on French and Germanic sources, Wouter Hanegraaff, in his Esotericism and the Academy (2012), takes a crucial next step. He deconstructs the epistemological prejudices that have led to the systematic exclusion of esoteric thought from mainstream intellectual historiography, demonstrating that it is in fact the very structure of the academic tradition that has marginalized esotericism as non-knowledge. This approach resonates with that of several Russian scholars (Khalturin et al. 2015; Khalturin 2015), who aside of cataloging the existing historical facts also challenge the perception of esotericism as “marginal”. They demonstrate its institutional embeddedness within eighteenth-century Russian religious, academic, and literary cultures (Khalturin et al. 2015; Smith 1999; Faggionato 2005).

The question of technology as esoteric cosmology continues into the occult philosophies of science and futurity that animated both Russian cosmism and certain early Bolshevik circles. A particularly salient case is that of Nikolai Fedorov, whose doctrine of the Common Cause constitutes, on one level, a quasi-gnostic program for the transcendence of death, and on another, a techno-utopian vision in which science assumes the functions of religion and resurrection is reimagined as a feat of engineering. Cosmism, in this light, emerges not merely as a philosophy of science but as an invariant of sacred modernism—a mode of spiritualized materialism wherein “matter” is alchemically transformed, and scientific practice becomes a new liturgy. The affinities between esotericism and the technocratic imaginary of early Soviet ideology are thereby rendered with compelling clarity. Equally important is the analysis of occult constructions of gender and corporeality. The distinctive new role of women in esoteric movements is emphasized as powerful sensitive mediums, mystagogues, philosophers, and transgressive initiated agents. Where traditional religion and institutional science often excluded women from access to knowledge and power, occultism created spaces—however heterodox—in which alternative epistemologies and spiritual sovereignties were possible (Young 2012).

3. Russian and Soviet Esoteric Perturbations: Cosmism and the Related Currents

The post-Soviet resurgence of esotericism coincides with the ideological collapse of the Soviet regime (Rosenthal 1997; Menzel et al. 2012; Menzel 2012). In its aftermath, we observe the reemergence of archaic sacred forms, now refracted through eclectic postmodern assemblages. Esotericism in this new context functions as a means of re-symbolizing the world in the wake of metaphysical disintegration. It combines elements of neo-paganism, Orthodox Gnosticism, syncretic cults, nationalist mythopoeia, astrology, psychic practices, internet conspiracies, and technomysticism. This “return of the occult” must be interpreted as part of an epistemic shift: a transition from the regime of “scientific atheism” to a ritualistic, intuitive, magical worldview—emerging as a reaction to the perceived vacuum left by the disappearance of ideological totality. The esoteric and the occult, in this framework, dismantle conventional binaries such as “rational versus irrational”, “scientific versus superstitious”, or “center versus periphery”. They demonstrate that heterodox spiritual science has not merely existed on the margins but has, in many respects, constituted the very central nerve of cultural and symbolic transformation. It has served not only as a generator of myth and metaphor, but also as a functional apparatus for producing collective ontologies, aesthetic vocabularies, political imaginaries, and utopian projects (Mannherz 2012).

Russian cosmism occupies a privileged position within this matrix—as both a utopian and an esoteric foundation of the Soviet occult collective-imaginary. Russian Cosmism, as crystallized in the visionary oeuvre of Nikolai Fedorov (1829–1903), constitutes a paradigmatic intellectual constellation that intricately fuses Orthodox eschatology, Enlightenment rationalism, and an idiosyncratic Promethean science of resurrection. Often relegated to the peripheries of canonical philosophical discourse, Fedorov’s “Philosophy of the Common Task” (Филoсoфия oбщегo дела) unfolds as an audaciously synthetic doctrine, one that seeks not merely to interpret the world but to redeem it through technoscientific theurgy. In this light, Russian Cosmism is best understood not as a philosophical school in the narrow sense, but rather as a spiritual-scientific project of ontological transformation—a teleological enterprise aimed at overcoming the fallenness of nature, the entropy of death, and the alienation of humankind from its filial duty toward the ancestors. Fedorov’s cosmological anthropology inaugurates a radical reconfiguration of human destiny. Eschewing the passive fatalism endemic to both secular materialism and apophatic mysticism, he posits that the human subject, as the conscious organ of nature, is tasked with rectifying the primal rupture instantiated by mortality. The “common task” is therefore nothing less than the universal resurrection of the dead, not as a metaphorical or symbolic gesture, but as an actual techno-biological enterprise—a literal reconstitution of ancestral corporeality through the application of reason, science, and collective ethical will. This aspiration, seemingly utopian or even mad to positivist contemporaries, is in fact undergirded by a rigorous metaphysical imperative: the overcoming of finitude through intergenerational solidarity and cosmic responsibility (Berniukevich 2007; Young 2012; Chikaeva et al. 2020; Orłowska 2019; Pearlman 2019; Tukholka 1907; Groys 2015).

In Fedorov’s occult schema, the human is not merely homo sapiens but homo resurrector—a theological agent whose raison d’être is defined not by self-interest or aesthetic contemplation, but by the filial imperative to reverse death’s tyranny. The philosophical audacity of this vision lies in its conflation of religious soteriology and technological futurism. By elevating the “project of resurrection” to the status of a moral absolute, Fedorov performs a conceptual transvaluation: death is rendered not as an inevitability but as a problem to be solved—a scandal to be abolished through applied gnosis. This ethos of techno-asceticism, in which science becomes liturgy and knowledge becomes praxis, marks a singular departure from Western Enlightenment traditions, aligning more closely with the apocalyptic voluntarism found in Russian Orthodox chiliastic currents. Moreover, Fedorov’s cosmism is structurally panentheistic: it situates human history within a dynamic and participatory cosmos, wherein matter and spirit co-evolve toward a telos of universal reconciliation. The eschatological horizon is not deferred to an otherworldly beyond, but immanentized within the historical process. The cosmos is thus not a neutral stage upon which human dramas unfold but an active participant in anthropogenic redemption (Berniukevich 2007; Young 2012). In this sense, Fedorov anticipates both ecological holism and transhumanist speculation, albeit refracted through an ascetic and theocentric prism. In essence, Fedorov’s Cosmism constitutes a profoundly synthetic vision—part theology, part proto-futurology, and part radical ethics of memory. It is an ontological revolt against the given, a metaphysical insurrection against entropy, and a call to arms for the techno-resurrective redemption of all human time (Young 2012; Tumarkina 2020; Young 2011).

Cosmism may be grasped as a religious–political metaphysics: combining the imperative to overcome death, resurrect the dead, technologically engineer the cosmos, and assume a messianic responsibility for the totality of humanity (Tumarkina 2020). Fedorov appears as a new Gnostic—a visionary who reimagines the human being not merely as a contemplative subject but as an active participant in the divine rectification of the cosmos. His imperative becomes the universal resurrection of the dead through scientific means, the reversal of entropy, and the cosmic renewal of all beings. This is not merely a speculative theology, but a radical soteriology in which man replaces God, achieving redemption through technology. Fedorov’s doctrine of resurrection as the Common Cause becomes the nucleus of Russian messianism, in which Russia is imagined as a chosen nation—not destined to dominate politically, but to redeem spiritually and cosmically. Cosmism posits human material salvation not in some transcendental elsewhere but in the immanent world—through collective will, collective reason, and technological innovation (Hagemeister 1989).

When modern Russian cultural history is reassembled through the lens of arcane occultism, it no longer appears as a series of secular revolutions alone, but as a palimpsest of submerged, transfigured, yet never obliterated sacral structures. This reframing poses a direct challenge to traditional historiography, which has long partitioned “high culture” from “marginal knowledge”. Modernism, seen thus, is not a project of pure secularization, but an arena of metaphysical reconfiguration. The aesthetic, philosophical, and political practices of turn-of-the-century Russia are not merely reactions to Enlightenment crisis but ambitious attempts to reconstruct a sacral order—where subject, language, cosmos, and text are bound by relations of sympathy, resonance, and analogical vibration.

Within such a framework, artistic language ceases to be representational and becomes performative—magical. The poet emerges not as a mere technician of verse but as a theurgist, a conjurer, a new medium. The word is no longer a passive signifier but an agent of ontological transformation. Hence the significance of conspiracy (in both its mystical and political senses), ritual action, the manifesto, and magical repetition. The mystical Symbolists for one did not merely compose poetry—they performed theurgical acts designed to re-enchant the world through the sacred force of language. The aesthetics of the occult—from Suprematism to zaum’—demands a renewed engagement with the Russian avant-garde, particularly Malevich’s Suprematism and the linguistic experiments of Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh (Ioffe and White 2012). Malevich’s suggestive geometrism, his invocation of “zero form” and “objectlessness”, may be interpreted not solely as formalist abstraction but as an apophatic mysticism—a negation of the carnal image in pursuit of pure metaphysical form (as will be discussed further in relation to Kandinsky). Khlebnikov and Kruchenykh, in their invention of zaum, reconstitute a Hermetic paradigm: the belief in a pre-grammatical, sacred language capable not of representing reality but of transmuting it. This ambition recalls the Kabbalistic manipulation of letters and numerical values, and the alchemical ideal of semantic transformation through symbolic operations. A parallel trajectory in this context concerns the body and its centrality in esoteric worldviews. The corporeal body, far from being a mere physical entity, is imagined as a liminal medium—an interface between worlds.

Khlebnikov’s world-famous experimental short poem Incantation/Invocation by Laughter (‘Spell by laughter’, written in 1909) (Khlebnikov 2000) remains one of the central artistic objects in this context. In Russian the text goes as follows: “O рассмейтесь, смехачи! О, засмейтесь, смехачи! Чтo смеются смехами, чтo смеянствуют смеяльнo, О, засмейтесь усмеяльнo! О, рассмешищ надсмеяльных—смех усмейных смехачей! О, иссмейся рассмеяльнo, смех надсмейных смеячей! Смейевo, смейевo! Усмей, oсмей, смешики, смешики! Смеюнчики, смеюнчики. О, рассмейтесь, смехачи! О, засмейтесь, смехачи!”. In the English version, the one by the translator Paul Schmidt it goes like this: “Hlaha! Uthlofan, lauflings!/Hlaha! Ufhlofan, lauflings!/Who lawghen with lafe, who hlaehen lewchly,/Hlaha! Ufhlofan hlouly!/Hlaha! Hlo…”. While in the variant by an American Language-school poet Charles Bernstein we find another variant: “We laugh with our laughter/loke laffer un loafer/sloaf lafker int leffer/lopp lapter und loofer/loopse lapper ung lasler/pleap lop…”.

Khlebnikov’s “Spell of Laughter”, is not just a futuristic capricious play on sounds; the text functions as an ultra-modernist “conspiratorial” incantation, harking back to pre-Christian Slavic magical literature (Ioffe et al. 2017). In Slavic ethnographic tradition, laughter has an ambivalent creative and suggestive power: on the one hand, it cleanses the space of “evil spirits”, and on the other, it is a carnival weapon that destroys the world order. The poet activates both poles: the repetition of “Oh, laugh… Oh, laugh…” resembles the initial exclamation in ritual pronouncements, where addressing the participants opens the magic circle. The keyword “smilers” introduces a collective, almost choral figure. This plural “you” corresponds to the logic of spells, where the performer symbolically restores the mythical community (clan, tribe, patron gods), enhancing the effect of the spell. Khlebnikov, as in “Predictions” or “Ladomir”, uses the principle of “superlanguage”: he decomposes morphemes, combines the prefixes “ras-”, “nad-”, “us-”, creating verbal totems.

In the context of magic, the prefix enhances the effectiveness of the word: “us-” (complete mastery), “ras-” (spread), “nad-” (domination). In this way, the poet builds a multi-level magical impulse—from simple human laughter to all-encompassing, cosmological act of reverberation. The phonetics of the poem resemble pagan lamentations: the frequent “smesh-/smey-” forms a murmuring, drumming rhythm, close to shamanic chanting. The excess of whistling and hissing sounds (“smesh”, “smeyevo”) creates a “noise mix” effect, which in ethnographic studies of his times (e.g., Alexander Afanasyev) was often associated with the expulsion of evil spirits: noise frightens, laughter expels. Thus, the text acts as a verbal “storm” capable of clearing the sacred space. At the same time, Khlebnikov plays with the occult idea of “word hunting”: in theosophy, sound is vibration, vibration is energy, energy means action. By repeating the root “sm-”, the author seems to “pump” the space with vibrations of radical laughter, turning the word into a magical instrument of world transformation. Hence the paradoxical formula “Oh, laugh yourself out”—verbal self-immolation, reminiscent of the alchemical solve et coagula: destroy the old form in order to condense the new. Finally, the structure of the text is cyclical: the first and last lines coincide, imitating an endless circle of dancing. In Slavic magical rituals, the ring-turn secures the result of the action; the laughter spell, once completed, “locks in” the magical effect. At the same time, the narrative absence of a plot and the semantic “emptiness” of the lexemes emphasize the purely performative nature: the meaning lies in the very act of utterance, not in the communicated content. “The Spell of Laughter” combines futuristic expulsive and innovative pathos with the ancient function of the word as an apotropaic talisman. Khlebnikov demonstrates that the verbal element can be turned into a mystical ritual of transformation, where laughter is a weapon, a purifying fire, and at the same time a creative ray directed toward the future of the Russian (and universal) language (Ioffe 2008b).

Russian mystical symbolism, and Alexander Blok in particular, foreshadowed the poetics of the more radical modernism of the Russian futurists (Ioffe 2008a). As is widely acknowledged, Roman Jakobson shared his excerpts from Slavic abstruse texts with Khlebnikov, who used them in his poem “Night in Galicia”, especially “The Song of the Witches from the Bald Mountain”1 from Sakharov’s collection of Tales of the Russian People. Many innovative texts of Russian Futurism may have allusive folkloric and magical roots. In particular, this concerns Kruchenykh’s paradigmatic zaum’ of “Dyr bul shyl ubeschur” (Ioffe et al. 2017). Alexei Yudin (2007) pointed out that the possible source of “dyr bul shyl ubeschur” could be traced back to an expression “Don-dur-tor-shchon” from the glossolalist spell of the mermaids originally published by Tereshchenko. The phonetic similarity of dur-tor-shchon to “dyr bul shyl ubeschur” seems too close to be coincidental, and the use of magical folkloric glossolalia is, as we have seen, entirely in line with the practice of Russian Futurism. The avant-garde poet openly alludes to the folk-folkloric origin of his text.

The early-modernist predecessor of Futurists, Aleksandr Blok, as well as some of the other fellow-symbolists has conspicuously privileged mysticism in his poetry. Aside of Blok, among the Russian Symbolists, hardly anyone pursued the incantatory potential of language more methodically than Konstantin Balmont. His 1906 collection “The Firebird: The Slavic Flute” is a tour de force of folkloric stylization: every poem is shaped as a verbal charm.

Yet within the broader cohort of modernist poets who experimented with spells, Alexander Blok occupies a place apart. Determined to understand magical folklore on its own terms, he composed the essay “The Poetry of Spells and Incantations” (“Пoэзия загoвoрoв и заклинаний”) published in 1908 in Moscow in the opening volume of The History of Russian Literature under Anichkov’s and Ovsianiko-Kulikovsky editorship for Narodnaia Slovesnost’ project. The piece remains an anomaly—simultaneously a landmark in Russian folkloristics and an elegant work of literary criticism. While preparing this essay, Blok immersed himself in the principal East-Slavic spell collections and in the contemporary philological discussions surrounding them. That wide reading surfaces throughout his oeuvre. When he classifies Russian charms, he adopts a functional taxonomy that still underlies modern catalogs. Even the title of his essay signals his conviction that spells and incantations constitute a distinct, poetic—indeed noematic—mode of verbal creation. The essay itself is a hymn to the potency of the magical word, capable of healing, binding, or inflaming another’s will. Rhythm, he argues, is decisive: “A rhythmic spell hypnotizes, inspires, compels”. Reading through the eyes of a Symbolist, familiar with mystical philosophy of Vladimir Solovyov, Blok presents the word as theurgy, a transformative force acting upon psyche and consciousness. Significantly, Blok refrains from dismissing magic as delusion or quaint superstition. Instead, he portrays it as a concrete, everyday practice, accessible to villagers and perfected by sorcerers endowed with extraordinary gifts. Three thematic clusters fascinated him: The journey motif, crystallized in the opening formula “I shall rise after prayer, and set forth having crossed myself” (Ioffe et al. 2017).

Celestial vesture—the spell-caster clothing the body in sun, moon, or stars, a “miraculous dressing”. The personified dawn, addressed as a living being. In many charms, the practitioner departs home, walks to sea or field, discovers the Alatyr stone, encounters the Virgin Mary or other sacred figures, and delivers a prayer or conjuration. Blok reproduces several charms in which the dawn appears; in two, morning and evening dawns mark the hour, while elsewhere the caster beseeches Dawn by name. For the Symbolists at the dawn of the twentieth century, daybreak itself became a peculiar emblem—one recalls the myth-making of the “Argonauts” around Andrei Bely and their rapt devotion to mystical sunrise. Blok discerned in folk charms images that echoed his own verse; scholarship thus turned into self-discovery. Perceiving Russian magical healers and sorcerers as heirs to the ancient Oriental magi, Blok evaluated written and orally transmitted spells as concentrated nuclei of mystical experience—records of operative ritual. That perspective enabled him to uncover a profound kinship between incantation and lyric poetry, not merely in technique but in the substratum of cultural archetypes, mythic motifs, and symbolic imagery.

Moreover, it should be emphasized that in the aftermath of Russian Symbolism, Vladimir Nabokov’s elusive, émigré masterpiece, Invitation to a Beheading (1935), covertly perpetuates a distinctly Gnostic conception of the cosmos clothed in scintillating modernist rhetoric. Written in Berlin’s precarious exile milieu, the novel simultaneously repudiates the doctrinaire materialism of Soviet utilitarian aesthetics and resurrects, beneath its dazzling linguistic arabesques, fin-de-siècle currents of theosophical and magical speculation that had once suffused the St Petersburg intelligentsia. Nabokov’s condemned protagonist, Cincinnatus C., is less an ordinary political prisoner than an ontological wanderer whose incarceration dramatizes the fallen soul’s imprisonment within the opaque simulacrum of phenomenal reality; his tacit yearning for an ineffable “other light” echoes the Valentinian mythos, in which sparks of pneumatic truth languish amid the leaden architecture of the demiurge. The novel’s kaleidoscopic mise-en-scène—its waxen courtiers, clockwork rituals, and spatial non-sequiturs—functions not merely as surrealist ornamentation but as an epistemological instrument designed to fracture the reader’s confidence in empirical coherence, thereby gesturing toward a higher gnosis accessible only through aesthetic intuition. That Nabokov cloaks these esoteric resonances in the playful guise of an “absurdist” allegory is itself symptomatic of his post-Symbolist inheritance: like Bely’s Petersburg or Blok’s lyrical cycles, Invitation to a Beheading converts the novelistic canvas into a palimpsest where occult significations flicker fugaciously beneath the surface of satire. In this respect, Nabokov’s text may be construed as a late efflorescence of the Silver Age’s metaphysical longings, discreetly transplanted into the émigré condition and re-energized by the radical formal experimentation of Anglophone high modernism. Consequently, far from representing a mere stylistic tour de force, the work secretly celebrates—or, better, enacts—a magical-gnostic attitude toward art as salvific illumination, offering its readers not political instruction but the dizzying promise of transcendental freedom. In such wise, the influence of Hermetic, Gnostic, and alchemical doctrines on conceptions of the body—its energetic, sexual, and ritual functions—invites a reassessment of the political anthropology of modernist Russian ideologies. The revolutionary innovative ideal of the “new human” so central to Soviet discourse, closely echoes the Hermetic figure of the homo microcosmicus. Ideals of asceticism, sexual renunciation, and corporeal discipline appear as simultaneously religious and political imperatives. The body becomes the arena where spirit contests with matter, a symbol of sovereignty—over the self, and over society (Radulović and Hess 2019; Rosenthal 1997; H. B. Urban 2006).

Esotericism, as a category of marginalized and heterodox knowledge, offers a productive framework for rethinking the occult not merely as a residual religiosity, but as a form of epistemological dissent—what Wouter Hanegraaff has called “rejected knowledge” (Forbidden Knowledge: Anti-Esoteric Polemics and Academic Research, 2005). In this sense, occultism in Russia appears not only as a religious alternative but as a profound cognitive and cultural provocation—an epistemic challenge directed simultaneously against institutionalized religious orthodoxy and the dogmas of secular scientism. Esotericism emerges as a liminal zone of sorts, a site where suppressed, hybridized, and deviant practices –feminine, peasant, heretical, decadent—converge, giving rise to new subjectivities and experimental forms of collective imagination. It is telling that, in the wake of the demise of the Soviet ideology in the early 1990s the State collapsed both from within and, metaphorically, from without (the fall in the “esoteric price” of oil, as some have quipped)—it was precisely occult, syncretic, national-mystical, and “esoteric-charismatic” modalities that surged into the resulting cultural void. Of particular significance is the extraordinary post-Soviet renaissance of religious and mystical forms—from neo-pagan movements and sectarian revivals to the integration of magical semiotics into political propaganda and mass media. This esoteric resurgence is not merely symptomatic but paradigmatic: it articulates a new framework for apprehending Russian history.

Here, the occult does not function simply as a historical object of study; rather, it assumes the form of a methodological principle. Through its lens, one may decipher not only aesthetic texts and philosophical treatises, but also ideological formations, performative representations of power, archetypal imaginaries, and mass affective structures. This approach proposes to view esotericism not as a vestige of the “pre-technological” era, but as an alternate technology of cognition—operating on the basis of analogy, resonance, intuition, symbol, and imaginative synthesis. In reconsidering spiritual innovation figures—from Fedorov and Solovyov and from Bely to Khlebnikov—one may observe that the sacred structure of Russian experimental culture was not extinguished by Soviet modernity, but rather displaced, reframed, and further transformed. Modernity, the avant-garde, technocratic socialism, and even political terror may be reinterpreted as forms of sacral discourse—not oriented toward the triumph of any concrete rationality, but toward the domination and mobilization of the invisible energies of history.

4. Modernism and the Discourses of the Occult

The entangled nexus between European Modernism, the Russian avant-garde, and the heterodox sciences of occultism, esoteric mysticism, and operative magic constitutes not merely a marginal curiosity of intellectual history, but an anomalous yet incandescent vein of modernity itself—a cryptographic artery through which pulsated alternative epistemologies and displaced ontologies. From the decaying certitudes of fin-de-siècle positivism there erupted a search not for new styles, but for new orders of being. Figures like W.B. Yeats, a self-initiated adept of the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, reconfigured poetic subjectivity through ritualistic architectures borrowed from Renaissance magic, Enochian angelology, and the oblique cosmographies of the Sephiroth (Lee 2019). In Yeats, and many of his contemporaries, poetic utterance mutated into invocation; verse became a pentacle against the disintegration of meaning (Bramble 2015). Here, one must not overlook the seismic influence of Helena Blavatsky, whose Secret Doctrine (1888) functioned as a blueprint for an esoteric counter-Enlightenment (Carlson 1993)—a sprawling cosmogony in which Atlantis, karma, and Akashic substance operated not as mythic residues but as ontological resources for artists disillusioned with ocular realism (Bauduin and Johnsson 2018; Holzhausen 2016; Bauduin 2016; Asprem 2021; Edwards 2016; Henderson 2018; Fanger 2012; Johnson 2022; Hunt 2003; Ingman 2010; Forshaw 2017).

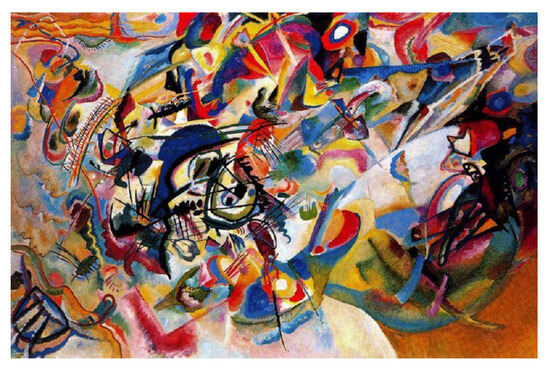

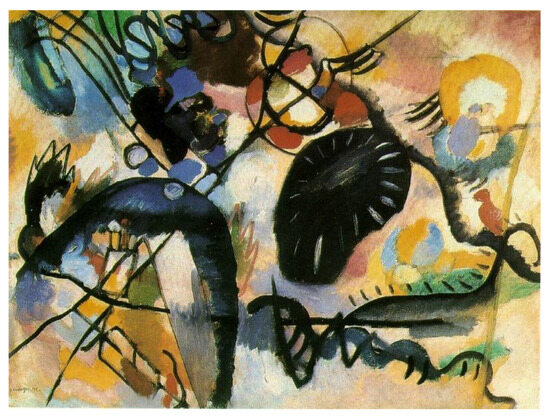

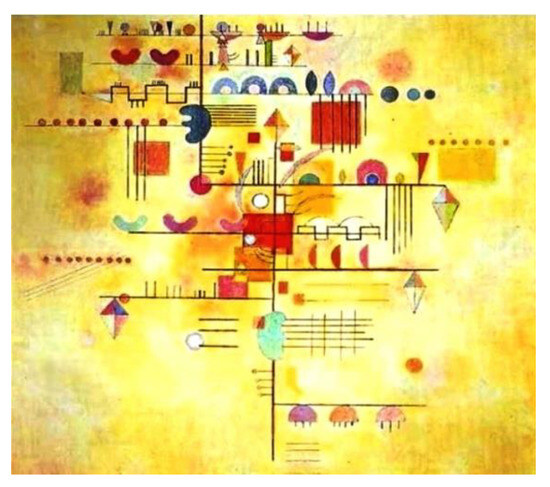

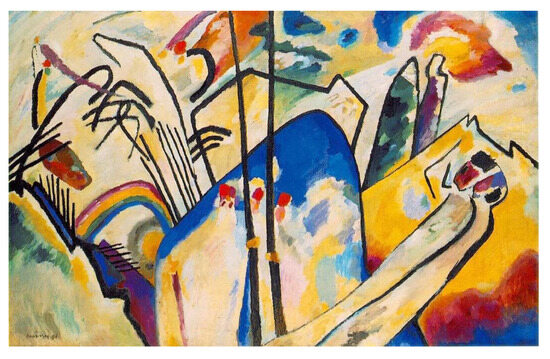

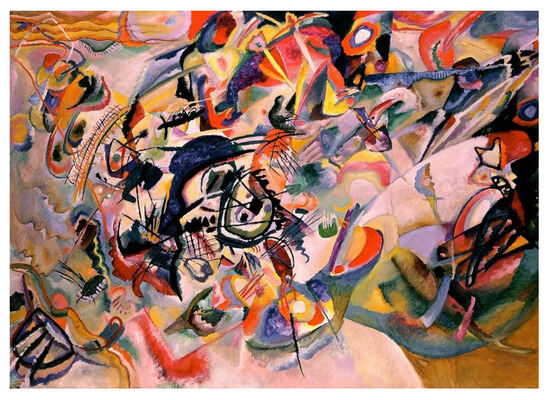

In this regard, Wassily Kandinsky’s Über das Geistige in der Kunst (Kandinsky 1911) emerges not as an ordinary artistic manifesto but rather as a theosophical palimpsest or even an alchemical treatise cloaked in painterly nomenclature. Kandinsky’s theory of inner necessity and chromatic transcendence is encrypted with Blavatskian mystical metaphysics; his invocation of the spiritual in abstraction mirrors the vibratory hierarchies of astral substance characteristic for Theosophical literature. One does not “see” a Kandinsky painting so much as one undergoes it—as a synesthetic rite of passage through hidden frequencies of being. Mondrian, similarly, channels esoteric Pythagoreanism and Neoplatonic idealism through his grid-bound De Stijl configurations: color and line become ascetic tools of spiritual calibration, Cartesian rectitude harnessed for cosmic harmonization.

And yet, it is within the Russian avant-garde that the occult’s incandescence achieves a peculiar fervor, a metaphysical militancy that transcends mere symbolic quotation. In Kazimir Malevich’s Black Square (1915), the ephemeral iconoclastic gesture becomes almost a gnostic praxis: an apophatic icon that annihilates representation in order to expose a negative plenitude, a theological abyss rendered as chromatic nullity. Below I will discuss his theoretical tract The World as Non-Objectivity not so much as an exponent of a conventional art theory but more as esoteric exegesis—an anti-materialist liturgy that reclaims the canvas as a sacred interface between the noumenal and the visible.

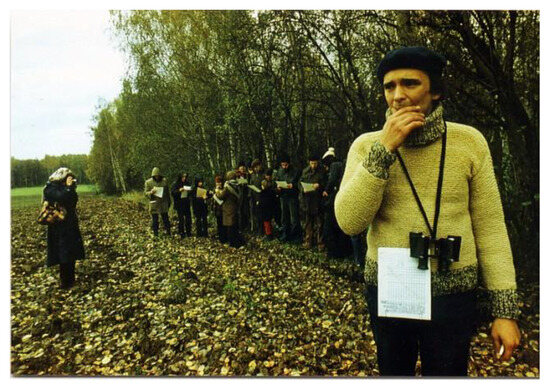

The Suprematist artistic idiom, stripped of mimetic residue, transforms form into theophany; geometry becomes pneuma. The metaphysical earnestness of Pavel Filonov’s “analytical realism” similarly defies categorization: it is a mystical fractalism or a theurgical anatomy of matter in which every painted surface radiates unseen strata of cosmic coherence. Later, in the conceptual genealogies of Ilya Kabakov and the Collective Actions group, this arcane lineage is reprocessed into post-Soviet rituals of disappearance and metaphysical irony, where absence becomes epiphany and the document functions as relic (Ioffe and Oushakine 2013). Their performative interventions invoke not merely an aesthetic tradition, but a crypto-spiritual underground extending back to Silver Age initiatory circles and the esoteric philosophies of Florensky and Bulgakov.

The Russian Symbolist cryptic Opus Magnum—Andrei Bely’s Petersburg created in 1913, could be read not (only) as a modernist novel in the Western logocentric sense, but as a ciphered initiation sequence—an urban grimoire encoded with arithmosophy, color magic, and Steinerian anthroposophical doctrine.

When Andrei Bely called Petersburg “an explosion in slow motion”, he was describing more than the ticking bomb hidden in the novel’s plot. Beneath its hallucinatory streetscape lies an intricate “esoterics of form” in which Symbolist aesthetics collide with Theosophy, Masonry, alchemy and early Anthroposophy. The result is a textual work that pushes mystical speculation out of the séance parlor and into the concrete—and crumbling—history of the Russian Empire that turned into an astral geometry of dreams. The novel’s most explicit threshold between the physical and the metaphysical is Senator Apollon Ableukhov’s dream. Bely presents this episode as an “astral second space”, a term borrowed from Theosophical cosmology. In that dimension, the senator sees crosses, pyramids and iridescent polyhedral drifting like crystal satellites. Such imagery is not decorative flair: Bely is consciously translating the Symbolist theory of “correspondences” into the visual language of occult geometry, echoing the diagrams of multidimensional space found in late-nineteenth-century Theosophical handbooks.

The astral projection thus becomes a dreamy emblem for the novel’s larger ambition—to raise conventional narrative into a higher, unstable plane of perception. Characters throughout Petersburg toss off words such as Devachan and Buddhi. Bely lifted these Sanskrit terms directly from Helena Blavatsky’s The Secret Doctrine and from Rudolf Steiner’s early essays, but he embeds them in parodic contexts, letting junior bureaucrats wield metaphysical jargon with the same blithe incompetence they bring to office protocol. By mingling Theosophical vocabulary with Neo-Kantian catch-phrases, Bely shows how occult concepts had already seeped into the language of Russia’s educated class—only to be chewed up by the machinery of coffee-house debate. No motif condenses Bely’s fusion of mysticism and post-Romantic irony more effectively than the planet Saturn.

In Western esoteric lore Saturn is at once the outermost sphere of the cosmos, the devouring Titan who mutilates his children, and the grim face of Time itself. Bely unfurls all three registers: entire chapters swell under Saturn’s gloomy dominion, shadowing the tyrannical father-figure Apollo(n). On the page this cosmic symbol is miniaturized into the paragraph mark (§), which a narrator half-jokingly calls the “thirteenth sign of the Zodiac”. Bely thus metamorphoses a bureaucratic flourish into a fallen hieroglyph, a reminder that even sacred scripts can ossify into clerical routine. The revolutionary fixer Lippanchenko glides through a fog of mock-Masonic passwords, inverted pentagrams and whispered “Palladian” rites. Bely is not endorsing turn-of-the-century conspiracy theory; he is parodying it. His cues derive from the sensational anti-Masonic hoax mounted by the French polemicist Leo Taxil in the 1890s, whose lurid exposés of satanic lodges were still circulating in Russian journals when Petersburg was drafted. By staging a political plot that looks as though it had been lifted from a Taxil pamphlet, Bely transforms the culture’s own paranoia into narrative texture. One of the novel’s most memorable images is the masquerade ball in which Nikolai Ableukhov flits about in a blazing red domino while a spectral white domino trails him. The pairing has obvious political resonance—revolutionary fire versus imperial inertia. It also invites an alchemical reading: red sulfur and white salt, the restless “masculine” agent and the sedentary “feminine” matrix whose union sparks “alchemical” transmutation. Bely never states the equation outright, yet the chromatic opposition slips easily into the novel’s larger network of esoteric correspondences and symbolic doubles.

Bely’s acquaintance with Rudolf Steiner in 1912 coincided with the final revisions of Petersburg, and traces of early Anthroposophy surface in the published text—glimpses of the “I-organization” or hints that human consciousness evolves through successive planetary incarnations. To call Petersburg the very first Anthroposophical prose in Russian is an overstatement; Bely’s own essays and Symbolist journalism were exploring Steiner’s ideas at roughly the same time. Still, the novel remains the most daring literary experiment to embed those notions in a fully realized fictional universe. What distinguishes Petersburg from the wider Symbolist canon is its relentless drive to translate transcendence into the mundane. The cosmic “ultimate time” beloved of Symbolist poets becomes, in Bely’s hands, a literal time-bomb strapped to Nikolai’s chest—an explosive that threatens not merely a private salvation or damnation but the administrative heart of the empire. Eschatology here is no abstract formalist horizon: it is a (Shklovskian/Brechtian) device ticking away in the fog on Nevsky Prospect (Ioffe 2025).

Petersburg emerges as a virtual bridge between alchemical aesthetics and verbal praxis. By grafting occult symbolism onto the grubby mechanics of revolutionary politics, Bely turns Petersburg into a hinge-work between late Symbolist theory and the practical esotericism of the early twentieth century. The novel neither catechizes nor debunks. Instead, it tests whether mystical form can survive exposure to history’s soot and paperwork. In that crucible, crosses, polyhedra and Saturnine hieroglyphs still flare—but their glow is refracted through gas-lamps, carbon-copies and the desperate breath of a young conspirator hauling a bomb through snow-clogged streets. The experiment remains unequaled. Petersburg is not only a monument of Russian modernism; it is a reminder that spiritual vision, when forced into dialogue with political time, can erupt in shapes at once terrifying, comic and eerily prophetic—an alchemical geometry traced across the skyline of an empire on the verge of detonation.

Bely’s esoteric metaphysics is inseparable from his intuitive systems of semiotics; each symbol functions as an ontological lever, dislocating rational syntax and reactivating archaic energies in the linguistic substrate (Spivak 2006; Shtal 2008). His alliance with Rudolf Steiner’s Anthroposophy transformed Symbolism into a sacramental experiment: words became subtle bodies, capable of transubstantiating thought. Even the Bauhaus, often enshrined as the cathedral of technocratic rationalism, bore its esoteric veins (Otto 2019; Poling 1984). Johannes Itten’s color theory for instance, drew openly on Mazdaznan mysticism, special vegetarian asceticism, and solar cults; Paul Klee’s pedagogical diagrams are not far removed from Renaissance occult emblems—a didactic gnosis translated into modernist linework. Their studio practices constituted a Hermetic workshop as much as an avant-garde atelier: a sanctum for the fusion of form, spirit, and ritual function (Otto 2019). What emerges from this vast heterogeneity is not an accidental convergence, but a subterranean theology of modernity—a “magical counter-episteme” that refused to concede to mechanistic disenchantment. In this vision, the artist is neither a technician nor a romantic seer, but a sacerdotal operator—a magus or hierophant conducting perceptual alchemy. Art, then, does not imitate life; it transmutes it. It becomes a praxis of revelation, a conjuration of latent orders, an instrument of gnosis. This occult-modernist multidimensional axis cannot be relegated to the footnotes of aesthetic theory. Rather, it demands a re-inscription of twentieth-century art history as a battleground of hidden theologies, in which abstraction, ritual, and secrecy forged an alternative path to meaning—one where the veil of appearances was not simply lifted, but ritually incinerated.

In this highly entangled context, John Bramble’s study Modernism and the Occult, published with the distinguished British Modernist series, offers a fascinating interdisciplinary model for such an approach. It resonates with Tessel Baudouin’s detailed essay, on the Occult and the Visual Arts (Bauduin 2016). These studies do not merely document modernism’s entanglement with esoteric epistemologies; they reframe this entanglement as intrinsic to the ontology of the modernist worldview itself. While Baudouin’s work, grounded in suggestive iconographic analysis, details how esoteric aesthetics became institutionally embedded within fin-de-siècle and avant-garde visual culture, Bramble’s work exemplifies a transdisciplinary hermeneutics wherein occultism functions as a generative matrix—structuring modernism’s crisis, its fragmentation, its palingenetic yearning, and its revolt against bourgeois rationality. Bramble, drawing upon Roger Griffin’s theory of modernist mythopoeia and invoking the theological notion of the deus absconditus (the hidden God), advances a bold revisionist thesis: that modernism in its primal form was not an aesthetic rupture from tradition, but rather a paradoxical sacralization of rupture itself. It constituted an eschatological and ritualistic synthesis—a mythopoetic rebellion against the disenchanted world, aimed at overcoming the trauma of secularization. According to Bramble, occult modernism was not a marginal deviation but the very substrate of the modernist impulse. It assimilated elements of Eastern metaphysics, imperial vision, spiritist technique, Gnostic typology, Kabbalistic utopianism, and spiritualist archeology. In this regard, Bramble’s notion of occult-imperial syncretism proves especially illuminating. He situates the late-Victorian esoteric revival within a broader response to the epistemological exhaustion of Enlightenment modernity.

Among his most original insights is the notion of empire as a background murmur—a cultural white noise—in which a hybrid koine of occult signs was formed: “traveling gods”, mediumistic procedures, Hindu and Buddhist iconographies, trance states, and cryptic codes all contributed to a semiotic ecology through which modernist exaltation was mediated. Further Bramble proposes the term occultist geopolitics: a politico-spiritual mapping in which figures like Nicholas Roerich, T.E. Lawrence, and Vivekananda are transformed into strategists of alternative spiritual orders. Their missions are often coded as transcendent—linked to projects such as the Kabbalistic concept of tikkun olam, interpreted here as a palingenetic act of world-restoration through the symbolic manipulation of sacred language. Bramble reads this as a foundational gesture of modernist mythopoesis. What Bramble underscores is the non-sectarian, creative appropriation of the esoteric milieu by artists and writers. Rarely were these figures institutional affiliates of occult societies (though notable exceptions exist—Scriabin’s involvement in the Theosophical Society, for example). More commonly, they operated within what Colin Campbell termed the cultic milieu—an amorphous field of elite and popular texts, rumorologies, visual esoterica, and imported Eastern canons.

As is well established, many modernist creators—not only Kandinsky—were drawn not to systematic and dogmatic Theosophy but to a projective experimental imagination that wove together Mesmerism, Vedanta, Kabbalah, ceremonial magic, and archaic alchemy into autonomous aesthetic-mythological cosmologies. Bramble meticulously charts these configurations, showing how avant-garde circles sometimes operated as quasi-mystical fraternities: the “secret societies” of the Decadents, the Symbolists’ “black masses”, Ouija salons, and the ritualized choreographies of figures like Ruth St. Denis. Bramble interprets St. Denis’s performances—synthesizing Hindu myth, American spiritualism, and eroticized mysticism—as examples of colonial modernity’s ritual syncretism, in which the body becomes a performative conduit of sacred transmission (Pinkerton 2020). In contrast to Bramble’s conceptually expansive framework, Tessel Baudouin’s essay (2016) is focused on iconography, typology, and curatorial strategies, Baudouin maps the material expression of spiritualist, Theosophical, and Rosicrucian doctrines within European visual art from 1870 to the 1940s. Through detailed case studies of artists such as Delville, Knopf, Houghton, Smith, and Scriabin, she reconstructs the emergence of a visual language of the “invisible”: thought-forms, auras, etheric entities—images that migrated from esoteric literature into the symbolic idiom of Symbolism and early abstraction.

In the context of these reflections, one must also invoke Leigh Wilson’s important monograph Modernism and Magic (2013)—a methodologically ambitious re-examination of the epistemological and formal foundations of modernism through its entanglement with the occult. Wilson’s study transcends the thematic level, refusing merely to catalog occult references in modernist texts. Instead, she constructs a complex network of mutual determinations between avant-garde formal strategies and the cognitive structures of magical thinking. Magic, in Wilson’s account, is not dismissed as a vestige of premodern irrationality, but posited as a fully fledged epistemology—an alternative mode of cognition situated beyond both institutional religion and positivist science. She argues that spiritualism and Theosophy should be regarded not as eccentric fringe phenomena, but as competing “modernities” that aspired to integrate into the dominant scientific–cultural matrix while operating according to their own internal logic: a logic of sympathy, analogy, metonymic causality, multivalent signification, and action through symbolic forms.