The Influence of Power on Post-Buyout Land Management Practices

Abstract

1. Introduction

1.1. Literature Review

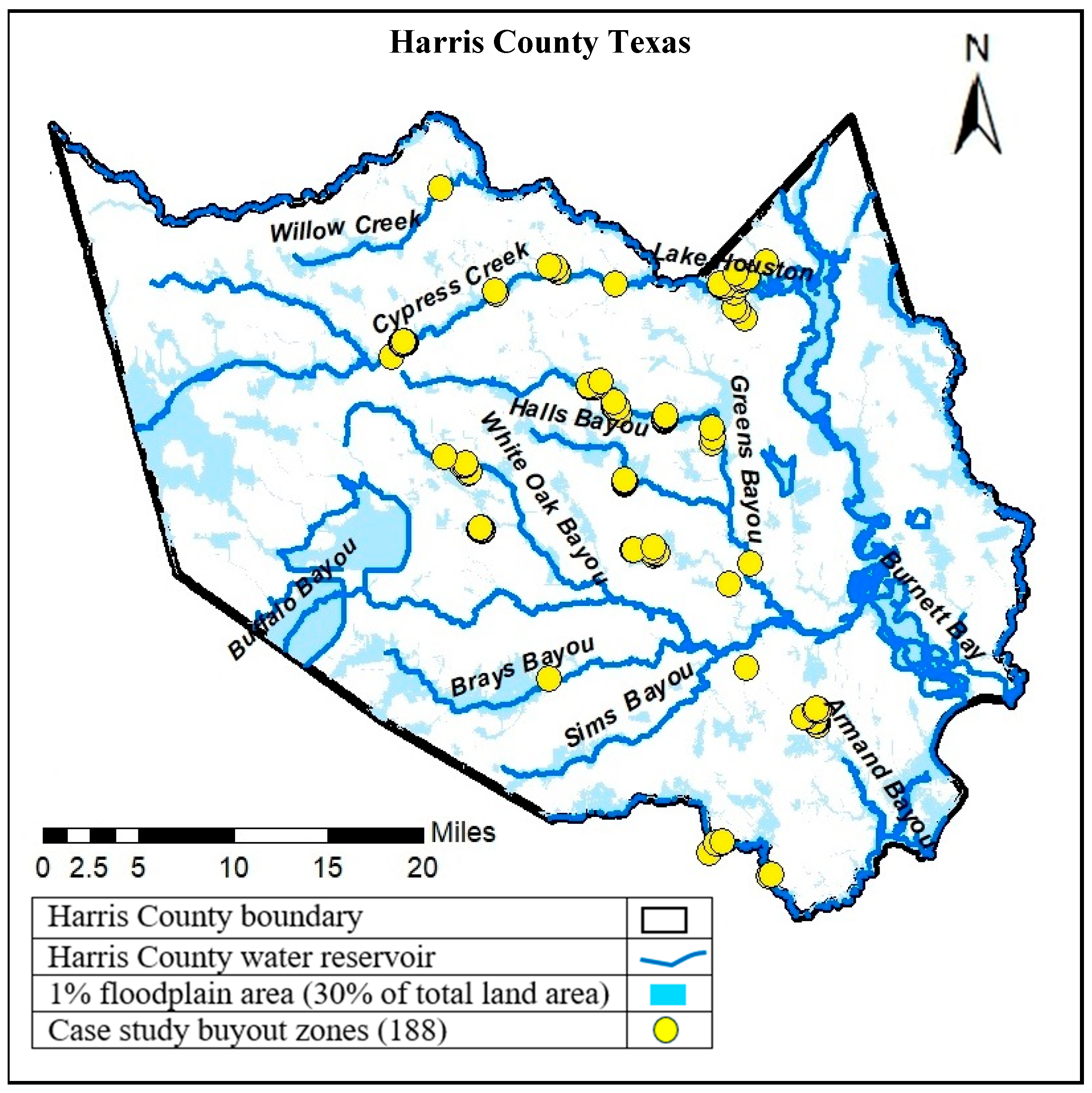

1.2. Harris County, Texas—Case Study

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Phase One—Data Collection

2.2. Phase Two—Coding

2.3. Phase Three—Spatial Analysis

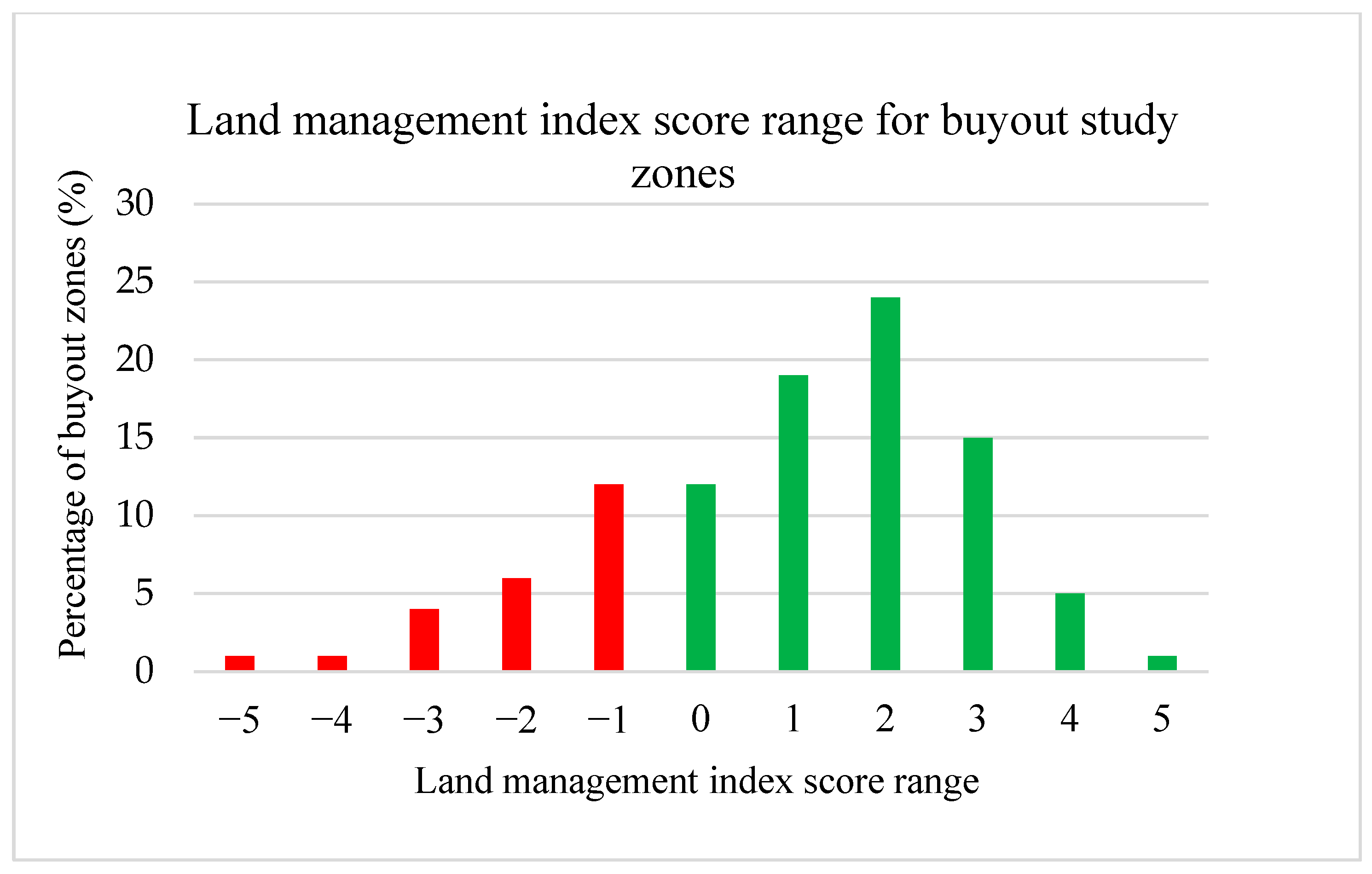

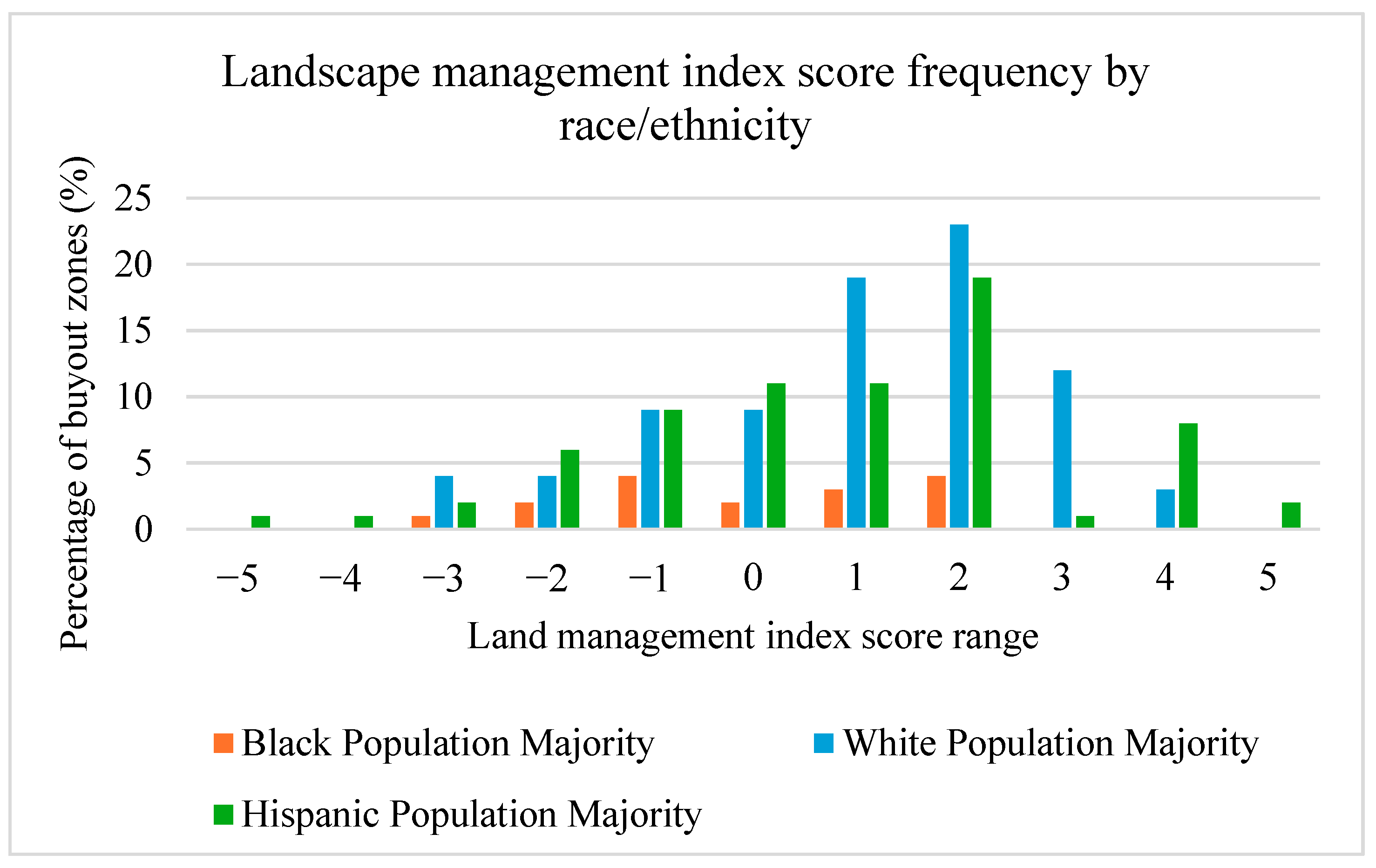

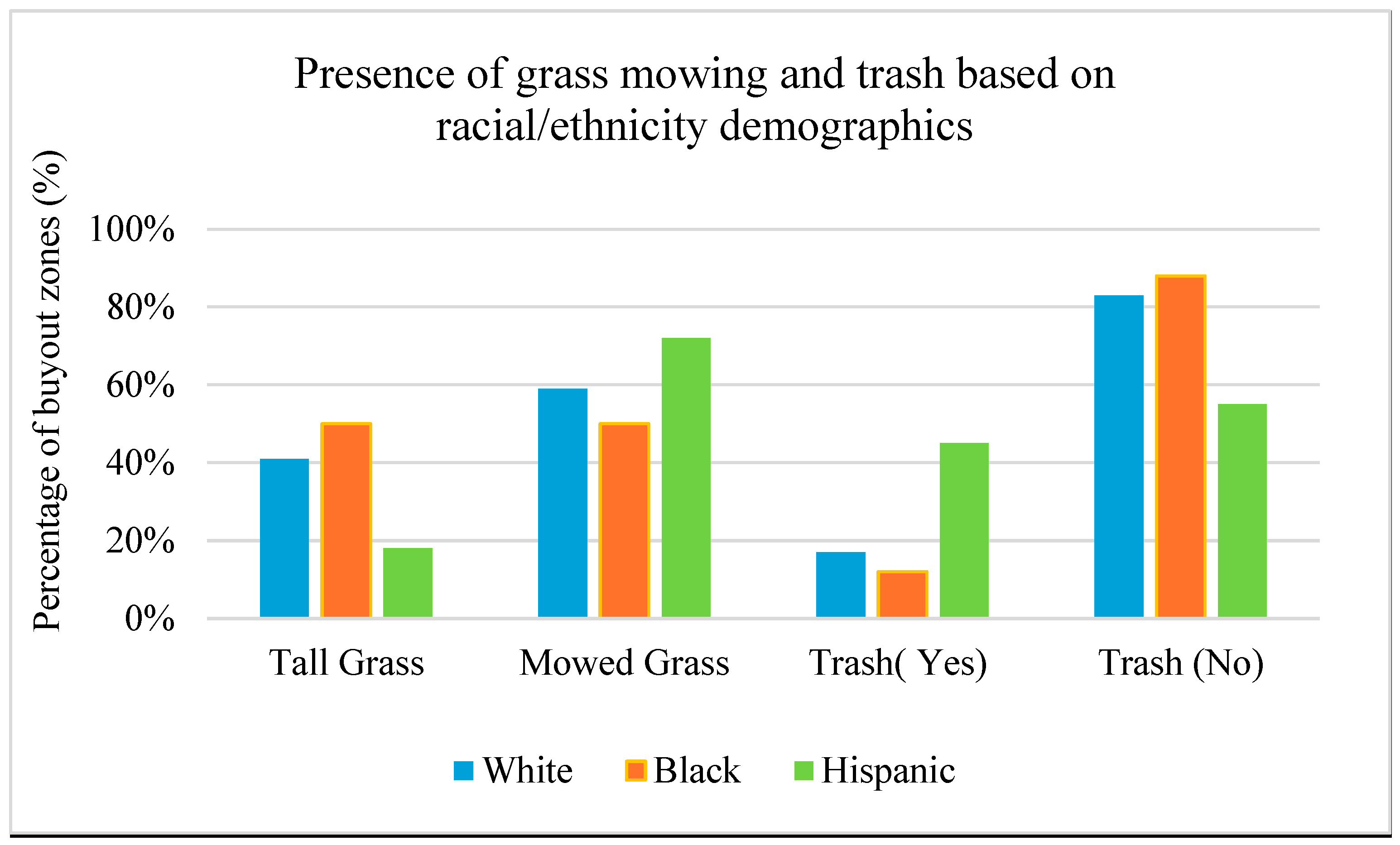

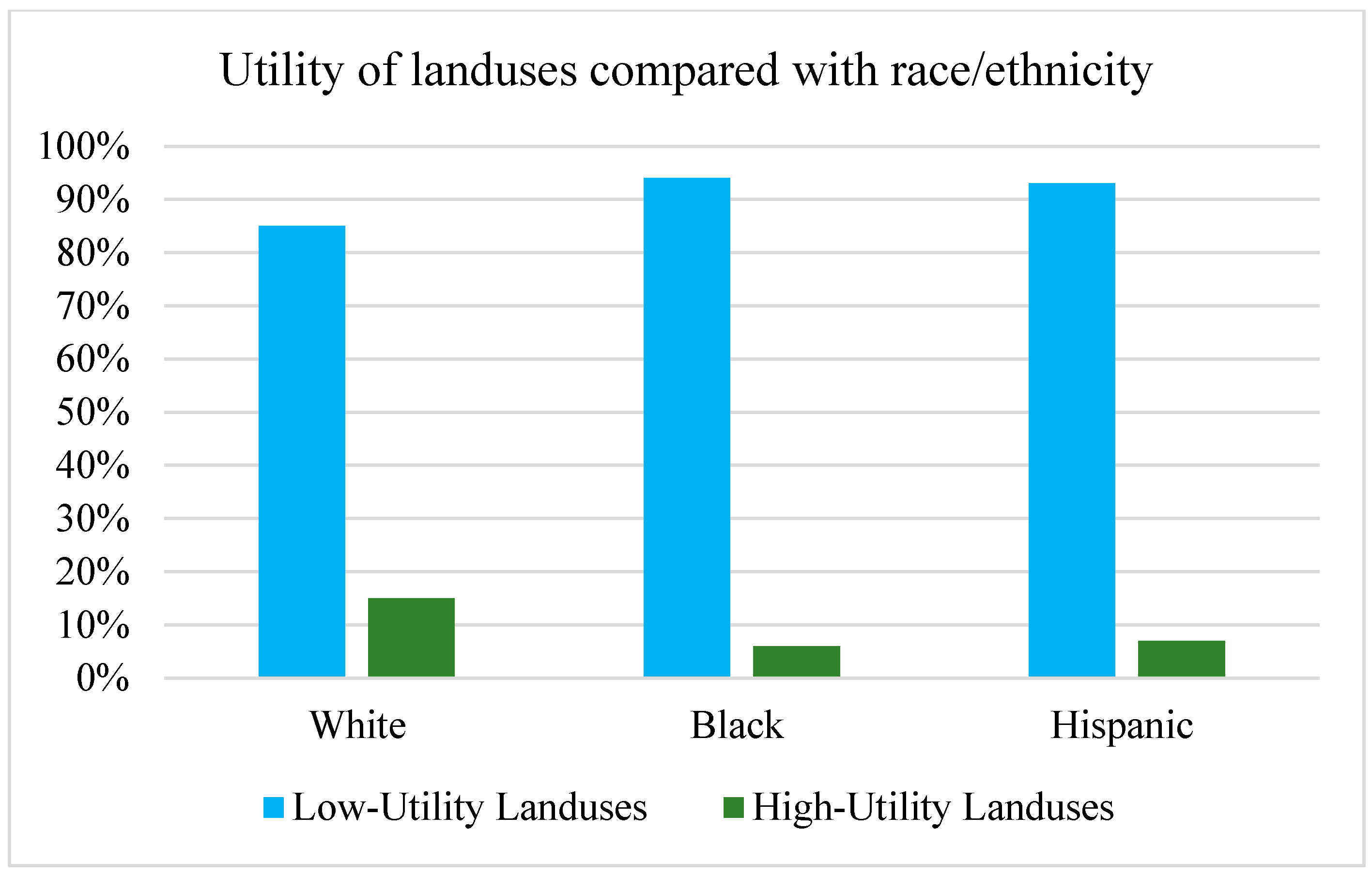

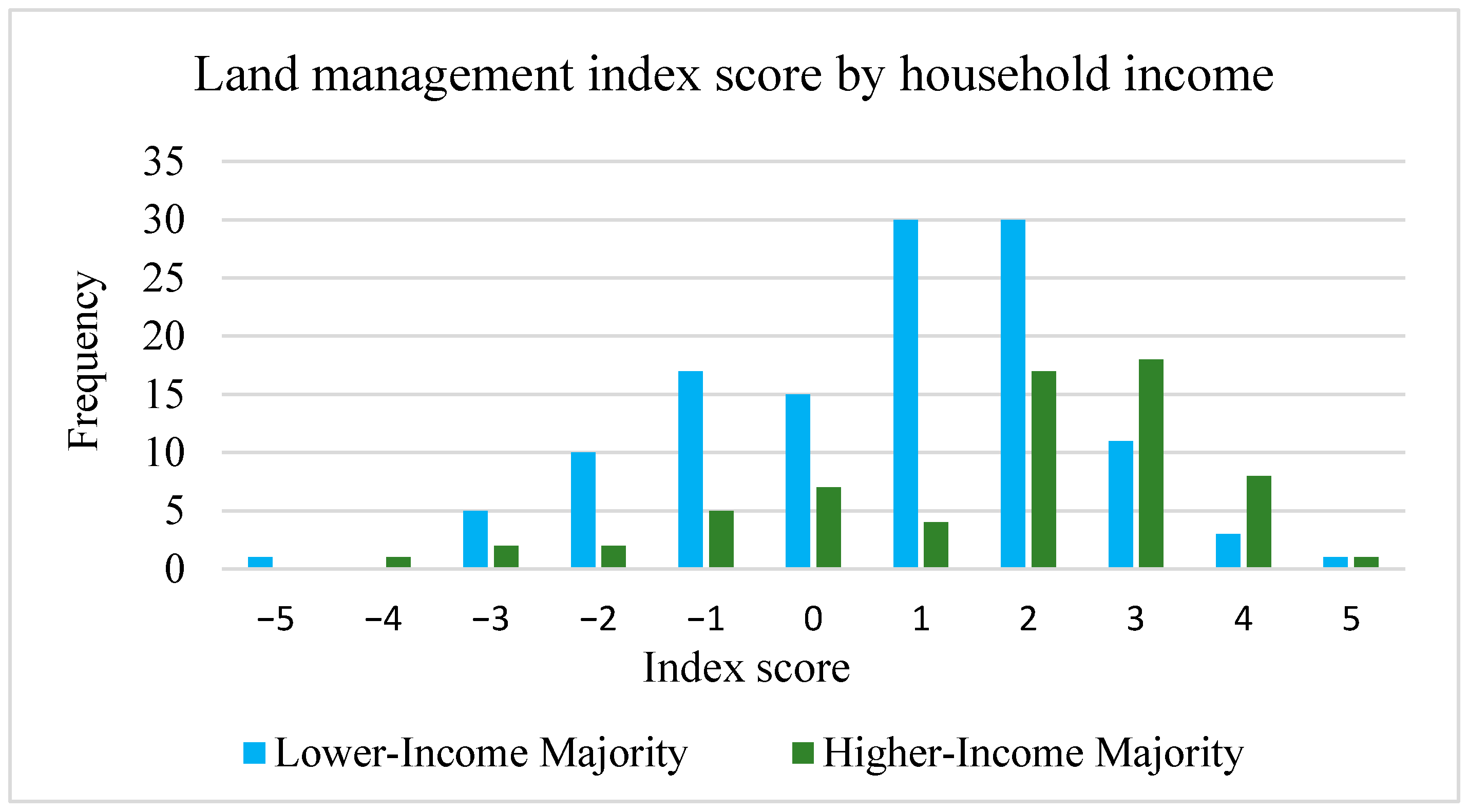

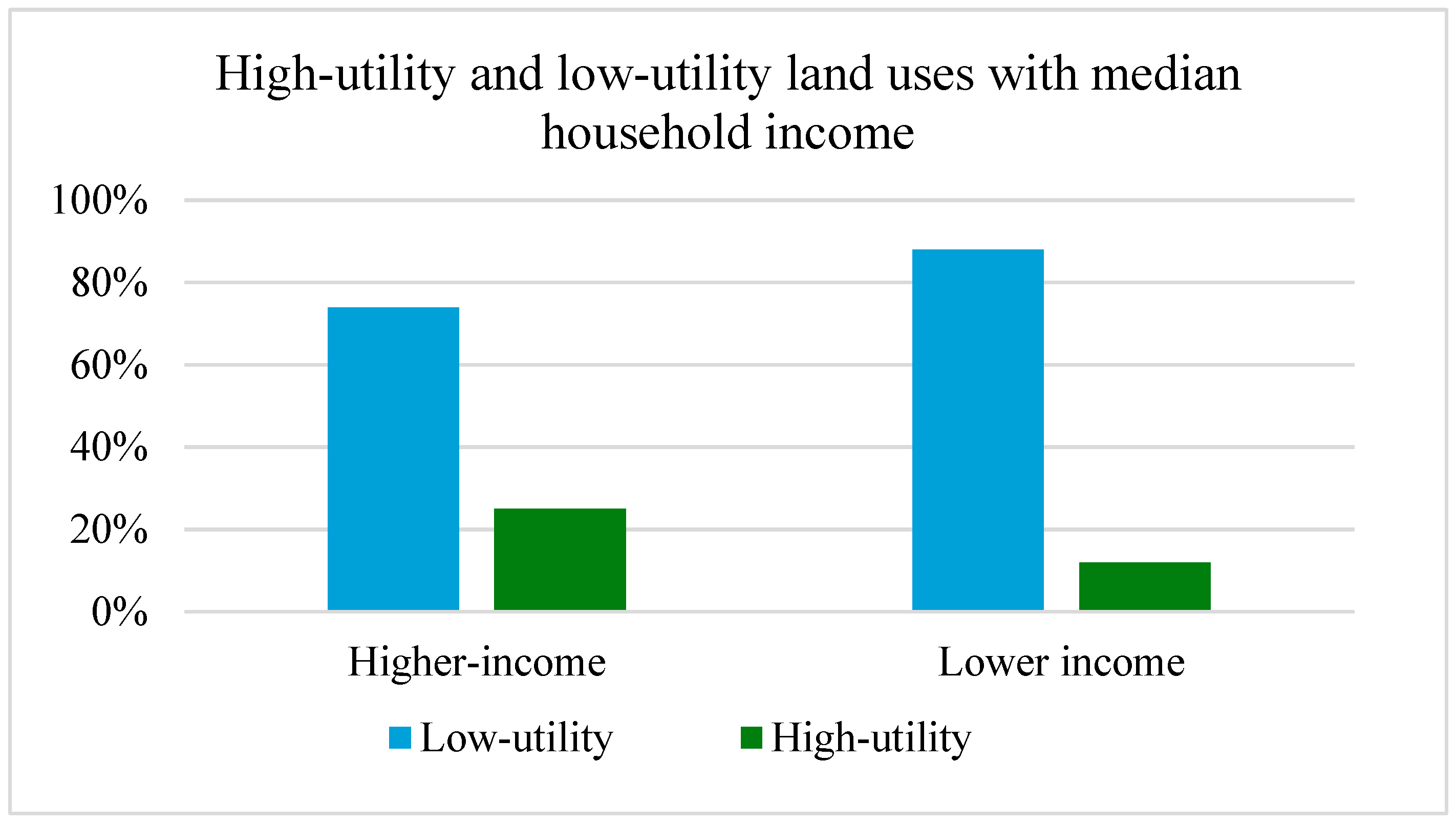

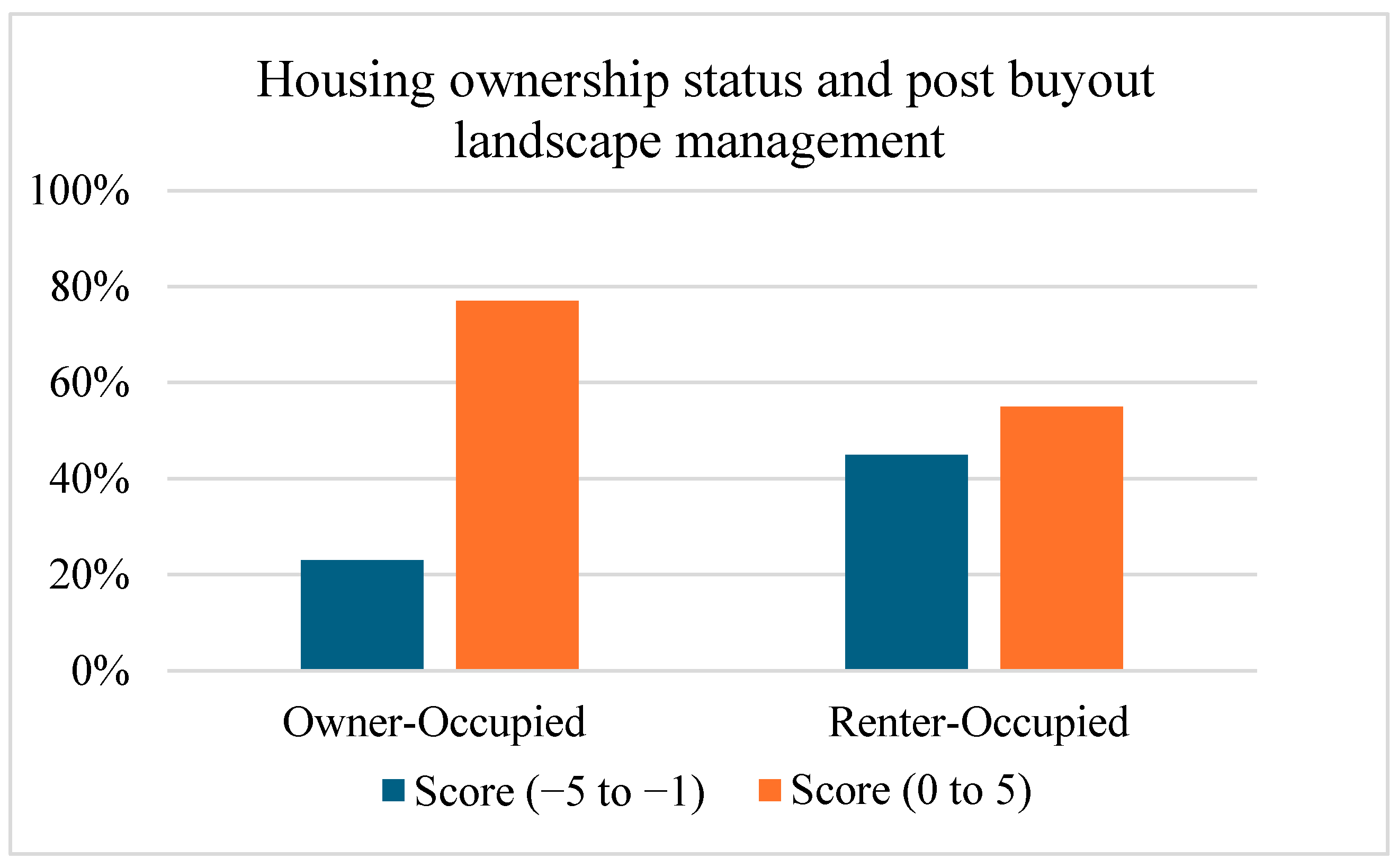

3. Results

3.1. Economic Status and Land Management Practices

3.2. Economic Status and Land Use Utility

3.3. Homeownership Status and Post-Buyout Land Management

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Atoba, Kayode, Galen Newman, Samuel Brody, Wesley Highfield, Youjung Kim, and Andrew Juan. 2021. Buy them out before they are built: Evaluating the proactive acquisition of vacant land in flood-prone areas. Environmental Conservation 48: 118–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Auer, Alejandra, Jonathan Von Below, Laura Nahuelhual, Matias Mastrangelo, Andrew Gonzalez, Mariana Gluch, Maria Vallejos, Luciana Staiano, Pedro Laterra, and Jose Paruelo. 2020. The role of social capital and collective actions in natural capital conservation and management. Environmental Science & Policy 107: 168–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baker, Donald. 2024. Race, Ethnicity and Power: A Comparative Study. Abingdon: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- BenDor, Todd, David Salvesen, Christian Kamrath, and Brooke Ganser. 2020. Floodplain Buyouts and Municipal Finance. Natural Hazards Review 21: 04020020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezerra, Maria Ometto, Derek Vollmer, Nicholas Souter, Kashif Shaad, Sarah Hauck, Maria Clara Marques, Silindile Mtshali, Natalia Acero, Yiqing Zhang, and Eddy Mendoza. 2023. Stakeholder engagement and knowledge co-production for better watershed management with the Freshwater Health Index. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 5: 100206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bin, Okmyung, Jamie Brown Kruse, and Craig Landry. 2008. Flood Hazards, Insurance Rates, and Amenities: Evidence from the Coastal Housing Market. Journal of Risk and Insurance 75: 63–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Binder, Sherri Brokopp, Alex Greer, and Elyse Zavar. 2020. Home buyouts: A tool for mitigation or recovery? Disaster Prevention and Management: An International Journal 29: 497–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boone, Christopher, Geoffrey Buckley, J. Morgan Grove, and Chona Sister. 2009. Parks and People: An Environmental Justice Inquiry in Baltimore, Maryland. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 99: 767–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkett, Maxine. 2015. Lessons From Contemporary Resettlement in the South Pacific (SSRN Scholarly Paper No. 3304939). Columbia Journal of International Affairs 68: 3304939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, Lauren, Mia Papas, David Abramson, and James Kendra. 2017. Social Capital, Neighborhood Disorder, and Disaster Recovery. Journal of Emergency Management 15: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohn, Avery, Peter Newton, Juliana D. B. Gil, Laura Kuhl, Leah Samberg, Vincent Ricciardi, Jessica R. Manly, and Sarah Northrop. 2017. Smallholder Agriculture and Climate Change. Annual Review of Environment and Resources 42: 347–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cottar, Shaieree, Brent Doberstein, Daniel Henstra, and Johanna Wandel. 2021. Evaluating Property Buyouts and Disaster Recovery Assistance (Rebuild) Options in Canada: A Comparative Analysis of Constance Bay, Ontario and Pointe Gatineau, Quebec. Natural Hazards 109: 201–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascher, Erin D., Elyse Zavar, Alex Greer, and Sherri Brokopp Binder. 2023. Biophilia as Climate Justice for Post-Buyout Land Management. Applied Geography 158: 103046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Daniel H., and James Fraser. 2012. Citizenship Rights and Voluntary Decision Making in Post-Disaster U.S. Floodplain Buyout Mitigation Programs. International Journal of Mass Emergencies and Disasters 30: 1–33. Available online: https://doi-org.libproxy.library.unt.edu/10.1177/028072701203000101 (accessed on 15 December 2024). [CrossRef]

- de Vries, Daniel H., and James Fraser. 2017. Historical waterscape trajectories that need care: The unwanted refurbished flood homes of Kinston’s devolved disaster mitigation program. Journal of Political Ecology 24: 931–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dineva, Polina, Christina McGranaghan, Kent Messer, Leah Palm-Forster, Laura Paul, and A. R. Siders. 2022. Promoting Spatial Coordination in Flood Buyouts in the United States: Four Strategies and Four Challenges from the Economics of Land Preservation Literature. Natural Hazards Review 24: 05022013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duncan, James, and Nancy Duncan. 2001. The Aestheticization of the Politics of Landscape Preservation. Annals of the Association of American Geographers 91: 387–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichhorst, Urda, and Ariadne Baskin. 2009. Adapting Urban Transport to Climate Change. Available online: https://changing-transport.org/wp-content/uploads/SUTP_Sourcebook5f-2_AdaptingTransport-to-ClimateChange.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Elliott, James, and Zheye Wang. 2023. Managed retreat: A nationwide study of the local, racially segmented resettlement of homeowners from rising flood risks. Environmental Research Letters 18: 064050. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elliott, James, Phylicia Lee Brown, and Kevin Loughran. 2020. Racial Inequities in the Federal Buyout of Flood-Prone Homes: A Nationwide Assessment of Environmental Adaptation. Socius: Sociological Research for a Dynamic World 6: 237802312090543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emrich, Christopher, Eric Tate, Sarah Larson, and Yao Zhou. 2020. Measuring social equity in flood recovery funding. Environmental Hazards 19: 228–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. 1998. FEMA Releases Affordability Framework for the National Flood Insurance Program. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/press-release/20230425/fema-releases-affordability-framework-national-flood-insurance-program (accessed on 10 May 2023).

- Federal Emergency Management Agency. 2008. Summary of FEMA Hazard Mitigation Assistance (HMA) Programs. Available online: https://www.fema.gov/sites/default/files/documents/fema_hma-program-fact-sheet_022023.pdf (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Fothergill, Alice, and Lori Peek. 2004. Poverty and Disasters in the United States: A Review of Recent Sociological Findings. Natural Hazards 32: 89–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freeman, Allison, and Kimberly Manturuk. 2019. Accommodating and Accumulating: How the Property Interests of Homeowners and Renters Impact Housing Satisfaction. In The Routledge Handbook of Housing Policy and Planning. London: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Gardinetti, R. Georges. 2022. Not in My Backyard: Policy Solution for Reducing Illegal Dumping in the Metro Vancouver Region. Simon Fraser University. Available online: https://summit.sfu.ca/item/35436 (accessed on 13 October 2022).

- Green, Timothy, and Robert Olshansky. 2012. Rebuilding ho using in New Orleans: The Road Home Program after the Hurricane Katrina disaster. Housing Policy Debate 22: 75–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harker, Julia. 2016. Housing Built upon Sand: Advancing Managed Retreat in New Zealand. Australian Journal of Environmental Law 3: 66–85. [Google Scholar]

- Harris County Flood Control District. 2022. Harris County’s Flooding History. Available online: https://www.hcfcd.org/about/harris-countys-flooding-history#:~:text=Nature%20always%20prevails,in%20just%20under%2070%20years (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Harris County Flood Control District. 2023. Mowing Schedule Explained. Available online: https://www.hcfcd.org/Resources/Interactive-Mapping-Tools/Mowing-Schedule-Explained (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Harter, Jana. 2007. Riparian Restoration: An Option for Voluntary Buyout Lands in New Braunfels, TX. Master’s thesis, Texas State University San Marcos, San Marcos, TX, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Henson, Margaret. 2020. Harris County, TSHA. Available online: https://www.tshaonline.org/handbook/entries/harris-county (accessed on 25 May 2023).

- Hersher, Rebecca, and Robert Benincasa. 2019. How Federal Disaster Money Favors The Rich. NPR. Available online: https://www.npr.org/2019/03/05/688786177/how-federal-disaster-money-favors-the-rich (accessed on 5 March 2019).

- Heynen, Nik, Harold Perkins, and Parama Roy. 2006. The Political Ecology of Uneven Urban Green Space: The Impact of Political Economy on Race and Ethnicity in Producing Environmental Inequality in Milwaukee. Urban Affairs Review 42: 3–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirokawa, Keith. 2010. Sustainability and the Urban Forest: An Ecosystem Services Perspective. Albany Law School Research Paper No. 36. Natural Resources Journal 51: 233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change. 2021. Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis, the Working Group I Contribution to the Sixth Assessment Report. Available online: https://www.unep.org/ndc/resources/report/climate-change-2021-physical-science-basis-working-group-i-contribution-sixth (accessed on 5 May 2023).

- Irwin, Elena. 2002. The Effects of Open Space on Residential Property Values. Land Economics 78: 465–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kraan, Caroline, Miyuki Hino, Jennifer Niemann, A. R. Sider, and Katharine Mach. 2021. Promoting equity in retreat through voluntary property buyout programs. Journal of Environmental Studies and Sciences 11: 481–92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loomis, Illima. 2018. Communities of Color Are More Vulnerable to Wildfires. Eos. Available online: http://eos.org/articles/communities-of-color-are-more-vulnerable-to-wildfires (accessed on 29 November 2018).

- Loughran, Kevin, and James Elliott. 2021. Unequal Retreats: How Racial Segregation Shapes Climate Adaptation. Housing Policy Debate 32: 171–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loughran, Kevin, James Elliott, and S. Wright Kennedy. 2019. Urban Ecology in the Time of Climate Change: Houston, Flooding, and the Case of Federal Buyouts. Social Currents 6: 121–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lynn, Kevin. 2017. Rising recreancy: Flood control and community relocation in Houston, TX, from an environmental justice perspective. Local Environment 22: 321–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mach, Katharine, Caroline Kraan, Miyuki Hino, A. R. Siders, Erica Johnston, and Christopher Field. 2019. Managed retreat through voluntary buyouts of flood-prone properties. Science Advances 5: eaax8995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manda, Simon, Alessandra Jerolleman, and Elizabeth Marino. 2023. Assumptions and understanding of success in home buyout programs. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 95: 103863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Massachusetts Institute of Technology. 2023. Living Wage Calculator. Available online: https://livingwage.mit.edu/ (accessed on 1 May 2020).

- McMichael, Celia, Katonivualiku Manasa, and Teresia Powell. 2019. Planned Relocation and Everyday Agency in Low-lying Coastal Villages in Fiji. The Geographical Journal 185: 325–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, Joan Iverson. 1995. Messy Ecosystems, Orderly Frames. Landscape Journal 14: 161–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nassauer, Joan Iverson. 1997. Placing Nature: Culture and Landscape Ecology. Washington, DC: Island Press, p. 179. [Google Scholar]

- National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration. 2013. Billion Dollar Weather/Climate Disasters. National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Available online: https://www.ncei.noaa.gov/access/billions (accessed on 26 February 2025).

- National Recreation and Park Association. 2023. Shady Lane Park Revitalization Parks Build Community National Recreation and Park Association. Available online: https://www.nrpa.org/our-work/parksbuildcommunity/Shady-Lane-Park-Revitalization/ (accessed on 16 April 2023).

- Nelson, Katherine, and Janey Camp. 2020. Quantifying the Benefits of Home Buyouts for Mitigating Flood Damages. Anthropocene 31: 100246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Connor, Cliodhna, and Helene Joffe. 2020. Intercoder Reliability in Qualitative Research: Debates and Practical Guidelines. International Journal of Qualitative Methods 19: 1609406919899220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ode, Åsa, Mari Tveit, and Gary Fry. 2008. Capturing Landscape Visual Character Using Indicators: Touching Base with Landscape Aesthetic Theory. Landscape Research 33: 89–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oldrup, Helene, and Trine Agervig Carstensen. 2012. Producing Geographical Knowledge Through Visual Methods. Geografiska Annaler. Series B, Human Geography 94: 223–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patterson, Grant. 2018. Case Studies in Floodplain Buyouts: Looking to best practices to drive the conversation in Harris County. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/1911/105221 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Patton, Michael Quinn. 2014. Qualitative Research & Evaluation Methods (Fourth). Los Angeles: The Sage. [Google Scholar]

- Piggott-McKellar, Annah, and Karen Vella. 2023. Lessons Learned and Policy Implications from Climate-Related Planned Relocation in Fiji and Australia. Frontiers in Climate 5: 1032547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinter, Nicholas, Mikio Ishiwateri, Atsuko Nonoguchi, Yumiko Tanaka, David Casagrande, Susan Durden, and James Rees. 2019. Large-Scale Managed Retreat and Structural Protection Following the 2011 Japan Tsunami. Natural Hazards 96: 1429–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Platt, Rutherford. 2014. Land Use and Society. Washington, DC: Island Press/Center for Resource Economics, p. 96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rigolon, Alessandro. 2016. A complex landscape of inequity in access to urban parks: A literature review. Landscape and Urban Planning 153: 160–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rohe, William, and Leslie Stewart. 1996. Homeownership and neighborhood stability. Housing Policy Debate 7: 37–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, Linda, Anjali Fisher, Rebecca Brenner, Amelia Greiner-Safi, Christine Shepard, and Jamie Vanucchi. 2022. Equitable buyouts? Learning from state, county, and local floodplain management programs. Climatic Change 174: 29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siders, Anne R. 2019a. Managed Retreat in the United States. One Earth 1: 216–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Siders, Anne R. 2019b. Social justice implications of US managed retreat buyout programs. Climatic Change 152: 239–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sister, Chona, Jennifer Wolch, and John Wilson. 2010. Got green? Addressing environmental justice in park provision. GeoJournal 75: 229–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, Gavin, Andy Fox, Travis Klondike, Abigail Black, Claire Henkel, Brian Vaughn, Chitali Biswas, Samiksha Bhattarai, and Samata Gyawali. 2023. Open Space Management Guide Building Community Capacity to Program FEMA-Funded Housing Buyout Land. Available online: https://doi.org/10.13140/RG.2.2.36360.19206 (accessed on 19 March 2022).

- Song, Lisa, Al Shaw, Neena Satija, ProPublica, and Texas Tribune Reveal. 2017. Buyouts Won’t be the Answer for Frequent Flooding Victims. ProPublica. Available online: https://features.propublica.org/houston-buyouts/hurricane-harvey-home-buyouts-harris-county/ (accessed on 1 November 2017).

- Stilgoe, Jack, Simon Lock, and James Wilsdon. 2014. Why should we promote public engagement with science? Public Understanding of Science 23: 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyler, Jenna, Abdul-Akeem Sadiq, and Douglas Noonan. 2019. A review of the community flood risk management literature in the USA: Lessons for improving community resilience to floods. Natural Hazards 96: 1223–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tzeng, Gwo-Hshiung, and Jih-Jeng Huang. 2011. Multiple Attribute Decision Making: Methods and Applications. London: Routledge. Boca Raton: CRC Press. [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2021. Data Profiles. Census.Gov. Available online: https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/acs/ (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2022. County Population Totals and Components of Change: 2020–2024. Census.Gov. Available online: https://www.census.gov/data/tables/time-series/demo/popest/2020s-counties-total.html (accessed on 28 December 2024).

- U.S. Census Bureau. 2023. U.S. Census Bureau QuickFacts: Harris County, Texas. Available online: https://www.census.gov/quickfacts/fact/table/harriscountytexas/VET605223 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Vanucchi, Jamie. 2023. Reconciliation or Restoration? The Ecological Futures of Floodplain Buyout Sites [Conference proceeding]. Managed Retreat Conference. Columbia University, New York. Available online: https://adaptation.ei.columbia.edu/managed-retreat-2023 (accessed on 15 December 2024).

- Yun, Lawrence. 2012. Benefits of Homeownership and Stable Housing. National Association of Realtors. Available online: https://www.nar.realtor/sites/default/files/migration_files/social-benefits-of-stable-housing-2012-04.pdf (accessed on 5 March 2022).

- Zavar, Elyse. 2015. Residential perspectives: The value of Floodplain-buyout open space. Geographical Review 105: 78–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavar, Elyse, and Lauren Fischer. 2021. Fractured landscapes: The racialization of home buyout programs and climate adaptation. Current Research in Environmental Sustainability 3: 100043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavar, Elyse, and Ronald R. Hagelman, III. 2016. Land use change on U.S. floodplain buyout sites, 1990–2000. Disaster Prevention and Management 25: 360–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavar, Elyse, Alex Greer, Sherri Brokopp Binder, and Sumaira Niazi. 2023. The expression of visual culture on flood buyout landscapes, Harris County, TX. GeoJournal 88: 5287–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavar, Elyse, Sherri Brokopp Binder, Alex Greer, and Amber Breaux. 2022. Using the past to understand future property acquisitions: An examination of historic voluntary and mandatory household relocations. Natural Hazards 116: 1973–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmermann, Karsten, and Dahae Lee. 2021. Environmental Justice and Green Infrastructure in the Ruhr. From Distributive to Institutional Conceptions of Justice. Frontiers in Sustainable Cities 3: 670190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Concept | Codes | Theory | References |

|---|---|---|---|

| Land use |

| Visual Structure of Landscape | (Ode et al. 2008) |

| Stewardship | Natural Environment

| Aesthetics of Care | (Nassauer 1995, 1997) |

| Confidence Level |

| Intercoder Reliability | (O’Connor and Joffe 2020) |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Niazi, S.; Zavar, E.; Greer, A.; Brokopp Binder, S. The Influence of Power on Post-Buyout Land Management Practices. Histories 2025, 5, 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5010014

Niazi S, Zavar E, Greer A, Brokopp Binder S. The Influence of Power on Post-Buyout Land Management Practices. Histories. 2025; 5(1):14. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5010014

Chicago/Turabian StyleNiazi, Sumaira, Elyse Zavar, Alex Greer, and Sherri Brokopp Binder. 2025. "The Influence of Power on Post-Buyout Land Management Practices" Histories 5, no. 1: 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5010014

APA StyleNiazi, S., Zavar, E., Greer, A., & Brokopp Binder, S. (2025). The Influence of Power on Post-Buyout Land Management Practices. Histories, 5(1), 14. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories5010014