1. Introduction

Virtual Reality (VR) technology has emerged as a transformative tool in preserving and interpreting heritage sites. By creating immersive, interactive experiences, VR enhances accessibility and engagement, allowing a broader audience to experience historical and cultural sites in unprecedented ways. The use of VR in heritage preservation is particularly valuable for maritime history, where physical access to vessels like the USS Drum submarine can be limited due to location, preservation concerns, and the physical condition of the sites. VR creates a simulated environment that can be explored in 360 degrees, offering a sense of presence and interaction that traditional media cannot provide (

Gutierrez et al. 2008;

Liu et al. 2023a). It allows users to navigate through virtual spaces, interact with objects, and access multimedia content such as audio, video, photographs, and text, enhancing their understanding and appreciation of heritage sites (

Yung et al. 2021).

The COVID-19 pandemic has profoundly impacted the tourism industry, causing a sharp decline in visitor numbers due to travel restrictions and social distancing measures. Museums and heritage sites were particularly affected, as physical visits became impossible for extended periods (

Sofaer et al. 2021). Virtual tours (VTs) have emerged as a vital tool in this context, allowing museums to reach their audiences digitally and maintain engagement during the pandemic (

Spennemann 2021;

Burke et al. 2020).

The USS Drum (

Figure 1), a Gato-class submarine that served during World War II (WW II), is an American National Historic Landmark (NHL) located at the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, Alabama (

USS Drum—USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park n.d.). Maritime museums, like the USS Drum Submarine Museum, present unique challenges for visitors, especially those with reduced mobility. The physical constraints of navigating through narrow passages and steep stairs can make these sites inaccessible for some (

Montusiewicz et al. 2018;

Pieters 2017;

Gül and Erk 2021;

Reyes-García et al. 2021;

Perez et al. 2019). VR and VT technologies can address these issues by providing a virtual alternative that replicates the experience of a physical visit without the associated mobility challenges. Through the technologies, visitors can explore every part of the vessel, view detailed 3D models, and access additional information that enhances their understanding and appreciation of the site (

Sobota et al. 2017;

Campitiello et al. 2022;

Luz et al. 2020).

This research study aims to develop and evaluate an immersive 360-degree VT of the USS Drum Submarine Museum. The project seeks to utilize VR technology to create an accessible and engaging digital experience that addresses the challenges of preserving and presenting this maritime heritage site. The specific objectives are to develop the USS Drum VT using 360-degree photography technology, integrating multimedia elements and oral histories; to conduct a user experience study to gather and analyze visitor feedback on visual quality, navigation, and the impact of oral histories; and to evaluate the effectiveness of the VT.

This article is structured as follows:

Section 1 provides an overview of VR technology in heritage preservation and the specific challenges faced by the USS Drum Submarine Museum.

Section 2 examines the existing research on VR in tourism and museums, VTs in heritage preservation, and Matterport technology and its applications in heritage documentation.

Section 3 details the development process of the VT, including the incorporation of multimedia elements and oral histories, and describes the user experience study design and execution.

Section 4 presents the completed VT of the USS Drum, findings from the user feedback survey, and an analysis of the effectiveness of the VT in enhancing visitor engagement and historical understanding.

Section 5 summarizes the key findings, discusses the contributions of the study to historical preservation, and suggests directions for future studies.

This paper uses multiple abbreviations to refer to various terms and concepts. To avoid confusion and ensure clarity, we provide the following list of these abbreviations and their corresponding meanings:

AI: Artificial Intelligence

AR: Augmented Reality

BMP: Alabama Battleship Memorial Park

NHL: American National Historic Landmark

RC: Reality Capture

UAV: Unmanned Aerial Vehicle

USS Drum: USS Drum Submarine Museum

VR: Virtual Reality

VT: Virtual Tour

WWII: World War II

2. Literature Review

2.1. Virtual Reality in Tourism and Museums

VR is a computer-generated simulation of a three-dimensional environment that can be interacted with using specialized electronic equipment, such as VR headsets and motion sensors (

Gutierrez et al. 2008). In tourism, VR enables users to virtually visit and explore destinations, providing an engaging and interactive alternative to physical travel. This technology enhances user experience by offering a dynamic way to learn about and appreciate different cultures and locations (

Buhalis et al. 2021;

Cruz-Neira et al. 1992;

El-Said and Aziz 2022;

Kiy 2019).

The virtual environment can be experienced in many ways, including form factors such as desktop computers, mobile tablet devices, smartphones, and head-mounted devices (

Cruz-Neira et al. 1992).

Boas (

2013) reasoned that VR is specifically successful when it is capable of immersion, perception, and telepresence. Exploring these three facets of VR is necessary when considering the effectiveness and quality of viewer experience. All VR systems have varying levels of immersiveness, perception, and telepresence (I.P.T.), and it could be argued that no system today can completely render a VR environment that replaces every human sense (

Kim and Leathem 2018).

Figure 2 illustrates some available VR form factors and contrasts a non-quantitative representation of I.P.T. available within each form factor.

Museums and tourism have increasingly adopted VR to create immersive exhibits that attract and engage visitors. VR allows museums to offer VTs, interactive displays, and reconstructed historical environments, providing deeper insights into their collections. The technology makes exhibits more accessible to a global audience, including those unable to visit in person (

Priolo et al. 2017). Furthermore, VR can bring to life artifacts and environments that are too fragile, rare, or dispersed to be displayed physically, thus preserving cultural heritage in a new, innovative manner. The immersive nature of VR offers several benefits for enhancing visitor experiences in museums and tourism. First, VR provides a highly engaging and interactive experience, allowing users to explore environments, interact with objects, and access multimedia content that enriches their understanding (

Huang et al. 2021;

Bozzelli et al. 2019;

Mantovani 2003). Second, VR makes cultural and historical sites accessible to a wider audience, including those with physical limitations or those who cannot travel, thus promoting inclusive education and broadening the reach of museums (

Stylianidis 2020;

Roussou 2002;

Paladini et al. 2019). Third, it offers significant educational benefits by providing immersive learning experiences where users can explore historical events, understand complex systems, and visualize abstract concepts in a more tangible and impactful way (

Fabris et al. 2019;

De Freitas et al. 2010;

Fromm et al. 2021). Lastly, the immersive experience of VR can create strong emotional connections with the content, enhancing memory retention and the overall impact of the exhibit or tour (

Han et al. 2019;

Flavián et al. 2021).

Published case studies highlight the successful implementation of VR in museums and tourism. The British Museum, for instance, has used VR to create an immersive experience of the Bronze Age, allowing visitors to explore artifacts in a virtual environment that simulates their original context (

Puig et al. 2020;

Gaugne et al. 2018). Similarly, the Smithsonian Institution has developed VR experiences that allow users to explore the Apollo 11 mission, providing an immersive way to learn about space exploration (

Zhang 2013;

Tylko 2023). The Louvre Museum also offers VR experiences that take users on a VT of the museum, including areas not accessible to the public, such as rooftop views and conservation laboratories (

Online Tours—Enjoy the Louvre at Home! n.d.).

2.2. Virtual Tour in Heritage Preservation and Interpretation

VTs have emerged as a pivotal technology in heritage preservation and interpretation, offering an innovative way to document heritage assets (

Liu et al. 2022) and make cultural sites more accessible (

Garau and Ilardi 2014;

Hausmann et al. 2015). A VT is a simulation of an existing location, usually composed of a sequence of videos or still images, which can also include multimedia elements such as videos, sound effects, music, narration, photographs, and text. VTs allow users to explore and interact with a space remotely, providing a rich and engaging experience that transcends the limitations of physical visits. The concept of a VT revolves around creating a digital representation of a physical space that users can navigate interactively. Components of VTs typically include high-resolution panoramic images, interactive hotspots, and embedded multimedia elements. These features work together to create an immersive experience that mimics a real-world visit. Users can access detailed information by clicking on hotspots, view related images and videos, and sometimes interact with virtual objects (

Churchill et al. 2012;

Fabroyir et al. 2014;

Kuksa and Childs 2014).

Research has shown that VTs can significantly enhance visitor engagement. They provide an interactive platform that encourages exploration and learning, making the visitor experience more dynamic and memorable. A study by Yung, Khoo-Lattimore, and Potter (

Yung et al. 2021) found that VTs increase visitor satisfaction and engagement by providing a more personalized and interactive experience. The ability to explore a site at one’s own pace and access a wealth of multimedia content contributes to a deeper understanding and appreciation of the heritage being presented.

Numerous heritage sites and museums have successfully implemented VTs to enhance their offerings. For instance, the Google Arts & Culture project has partnered with museums worldwide to create VTs that allow users to explore art collections and historical sites from their homes (

Virtual Reality Tours n.d.). Another notable example is the VT of the Palace of Versailles, which offers an immersive experience of the historic site (

360° Virtual Tours 2024). The tour includes high-resolution images of the palace’s interior, interactive maps, and multimedia content that provide historical context and detailed information about the artifacts and architecture. This VT has been praised for its ability to make the grandeur and history of Versailles accessible to a global audience (

Wang et al. 2023).

Moreover, the COVID-19 pandemic highlighted the importance of VTs as an alternative to physical visits when access to heritage sites is restricted. During the pandemic, many museums and cultural sites turned to virtual visits to maintain engagement with their audiences. VTs became a crucial tool for education and outreach, allowing institutions to continue their missions despite the challenges posed by the pandemic (

El-Said and Aziz 2022).

The VT technology has proven to be particularly beneficial for maritime museums, where physical access to historical vessels can be challenging due to location, preservation concerns, and the inherent mobility issues associated with navigating narrow passages and steep stairs. By creating digital replicas of these vessels, VTs allow visitors to explore every aspect of the maritime heritage site remotely, providing an immersive and detailed experience that mimics a physical visit. For example, the Battleship USS Iowa Museum in Los Angeles has utilized VT technology to create a comprehensive experience of the USS Iowa (

Figure 3). This tour features high-resolution 3D imagery of the battleship’s interior and exterior, enhanced with multimedia elements such as photos, videos, and interactive hotspots that offer in-depth information about various parts of the ship and its history (

Online Tour & Museum—Battleship USS Iowa Museum 2020). As maritime museums continue to adopt VTs, they can help overcome the limitations of physical visits and provide inclusive, educational experiences that engage a diverse audience.

The Toti Submarine VR Experience at the Leonardo da Vinci Museum in Milan offers an immersive VT of the Enrico Toti submarine, launched in 2015, including a narrated guided tour and a 2D serious game to enhance the educational experience (

TOTI SUBMARINE VR EXPERIENCE n.d.;

Toti SubmarineVR Experience n.d.). This initiative exemplifies the effective use of VR technology in making complex historical artifacts accessible and engaging for a wider audience. However, this review of existing literature did not locate any studies on the virtual user experience evaluation of the utilization of the technology in maritime museums.

While VTs offer numerous benefits, they also present challenges. Creating high-quality tours requires significant resources, including advanced technology and skilled personnel (

Cardona et al. 2023;

Kask 2018). Additionally, ensuring that VTs are accessible to all users, including those with disabilities, can be challenging (

Buhalis and Michopoulou 2011;

Tolvanen 2023).

2.3. Matterport Technology

Matterport is a leading platform in the field of 3D spatial data capture, providing technology that allows users to create detailed, immersive VTs of real-world environments. The Matterport 3D cameras (e.g., PRO-2 and PRO-3 models) are the company’s primary tool, capable of capturing high-resolution 3D imagery and generating comprehensive digital models of spaces. The technology utilizes a combination of infrared sensors, LiDAR scanners, and high-definition cameras to produce accurate and photorealistic 3D representations, which can be navigated and explored virtually (

Matterport 2024).

Matterport technology has found significant applications in heritage documentation, providing an innovative solution for preserving and sharing cultural heritage sites. By creating detailed 3D models of historical buildings, artifacts, and environments, Matterport helps to digitally preserve these assets for future generations (

Liu et al. 2022;

Pulcrano et al. 2019;

Foo et al. 2023;

Liu et al. 2023c). This is particularly valuable for sites at risk of deterioration or are difficult to access (

Liu et al. 2023b). The technology allows for the documentation of intricate architectural details and spatial arrangements, which can be used for research, restoration, and educational purposes.

In museums and tourism, Matterport VTs offer a dynamic and engaging way to experience cultural and historical sites. Museums around the world have adopted Matterport to create VTs that allow remote visitors to explore their exhibits in detail. As shown in the Hood Museum’s Matterport virtual space (

Figure 4), the tours can include interactive elements such as descriptive text, audio guides, and embedded videos, enhancing the educational value of the virtual visit (

Explore Hood Museum Exhibitions through 3D Virtual Tours 2021). Matterport technology enables museums to reach a global audience, providing access to their collections to those who cannot visit in person (

Clerkin and Taylor 2021;

Resta et al. 2021). For example, the Sydney Opera House uses Matterport to offer VTs that showcase its iconic architecture and rich history, making the experience accessible to people worldwide (

SmartView Media 2021). In tourism, Matterport VTs allow potential visitors to preview destinations, helping them make informed travel decisions and generating interest in real-world visits (

Sann et al. 2023;

McLean and Barhorst 2022). The immersive quality of these tours provides a compelling way to experience and learn about new places from the comfort of one’s home.

The literature highlights the transformative impact of VR and VTs in the tourism and museum sectors, enhancing visitor engagement and accessibility. VR offers immersive, interactive experiences, while VTs provide detailed, remote explorations of heritage sites. Matterport technology further revolutionizes VTs by creating high-resolution 3D models that preserve and share heritage sites globally. Despite challenges such as resource demands and accessibility, VTs have proven crucial, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. The USS Drum Submarine Museum

The USS Drum (SS-228) is a Gato-class submarine that played a significant role during WW II. Commissioned on 1 November 1941, it completed 13 war patrols and was credited with sinking 15 enemy vessels, totaling 80,580 tons, making it one of the most successful submarines of the war. The USS Drum received 12 battle stars for its service. After the war, it was decommissioned on 16 February 1946, and later transferred to the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park (BMP) in Mobile, Alabama, in 1969 (

Figure 5a). As a National Historic Landmark, the submarine is the oldest American submarine on public display and serves as a key attraction at the park, which itself opened on 9 January, 1965 (

USS Drum—USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park n.d.). The BMP also houses the battleship USS Alabama (BB-60), various tanks, artillery, aircraft, and multiple memorials, including the Korean Memorial, Vietnam Memorial, POW Bracelet, and the Fallen Guardian Memorial. The museum attracts an average of 375,000 visitors annually, providing them with insights into naval warfare and the experiences of those who served on these historic vessels (

Home—USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park n.d.).

This USS Drum Museum offers a unique glimpse into the life and operations of a WW II submarine. Visitors can explore the submarine’s narrow passages (

Figure 5d), crew quarters, engine rooms, torpedo rooms (

Figure 5e), and control areas, gaining a deeper understanding of the challenges faced by its crew. However, this maritime museum presents significant challenges for visitors with limited mobility. The tight spaces, steep stairs, and narrow passages within the submarine make physical navigation extremely difficult, if not impossible, for some individuals. This limitation highlights the need for innovative solutions to enhance accessibility and ensure that all visitors can experience and learn from this important historical artifact.

3.2. Development of the Virtual Tour for USS Drum Submarine

The primary goal of creating the VT of the USS Drum is to allow users to explore the submarine from an accessible position with realistic sensations, mimicking an in-person visit. As illustrated in

Figure 6, the development process was divided into the following five main steps: preparation, on-site capture, collecting oral histories, post-capture processing and editing, and launching the VT.

Project preparation involved formulating a detailed plan for capturing the submarine’s spaces and narratives. The project team conducted extensive research to gather relevant historical records, photographs, and other artifacts to enhance the VT. During the on-site capture phase, a Matterport PRO-2 3D camera was used to digitize the physical spaces of the submarine (

Figure 7a), including its main deck (

Figure 7b), interior compartments, conning tower, and bridge. This process required over 300 stationary setups of the PRO-2 to ensure comprehensive coverage. Additionally, short films were recorded on-site featuring the USS Drum’s curator (

Figure 7c), who provided detailed explanations of various parts of the submarine. Next, the project team traveled to the state of Indiana and interviewed a veteran who served aboard the USS Drum as a radioman during WW II. The interview focused on his experiences during the war, and his oral histories were recorded to be integrated into the VT. Post-capture processing and editing included uploading the captured imagery to Matterport’s cloud server for processing. The platform automatically stitched the images together to create a seamless, navigable 3D model. The initial “raw” VT was then edited to enhance the user experience, ensuring the accurate alignment and calibration of the images. Multimedia elements, including photographs, videos, and oral histories (through YouTube), were embedded into the virtual space. Interactive hotspots were created, allowing users to access detailed information and narratives. Finally, the VT was launched on the BMP’s website, making the completed VT accessible to a global audience.

3.3. User Experience Study of the USS Drum VT

To gather feedback from virtual visitors on their experiences with the tour, the research team conducted a mixed-methods study using an online survey. The survey was designed to capture both quantitative and qualitative data. The types of questions included Likert-scale questions and open-ended responses. The Likert-scale questions were rated on a five-point scale, ranging from 1 (strongly disagree) to 5 (strongly agree), and covered various aspects of the VT experience. The questionnaire was divided into four sections. The first section collected demographic information. The second section focused on users’ opinions of the technical aspects of the VT, including ease of use, vividness and detail of imagery, and the informativeness of linked multimedia content. The third section assessed the visitors’ overall experience, measuring immersion, enjoyment, and educational value. The final section contained different sets of questions for users who had had previous in-person visits with the USS Drum and those who had not, allowing for a comparison between the VT and physical visits.

The survey was introduced to groups of students in a construction management program during a classroom session. This sample consisted of post-secondary students with a focus on the built environment, making them a convenience sample for gathering immediate perceptions about the virtual experience. After a 5 min introduction to the study, the students were given 15 min to explore the virtual tour. They were then directed to complete the online questionnaire. Quantitative data from the Likert-scale questions were analyzed to determine the overall satisfaction and engagement levels, while qualitative data from the open-ended questions provided deeper insights into users’ experiences and suggestions for improvement.

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Overview of the Completed Virtual Tour

The VT of the USS Drum Submarine Museum, built on the Matterport platform, offers an immersive and interactive experience for users. This digital replica allows users to navigate through the submarine’s various sections, including the main deck, interior compartments, conning tower, and bridge, providing a detailed and realistic representation of the submarine’s structure and layout. It features high-resolution 3D imagery that captures every aspect of the submarine (

Figure 8a). Users can explore the submarine as if they were physically present, thanks to the detailed and immersive imagery. The interactive navigation system (

Figure 8b), with intuitive hotspots, guides users from one section to another, allowing them to navigate the tight, cramped spaces of the submarine. Additionally, the VT offers a “dollhouse” view and multiple floor plans (

Figure 9), providing an external perspective of the submarine and its internal layout, helping users understand the overall structure and spatial arrangement.

The VT is also enriched with multimedia content, including video narratives and oral histories, which are presented through “tags” within the tour. These tags are strategically placed throughout the submarine. Short films featuring the USS Drum’s curator provide detailed explanations of various parts of the submarine, offering insights into the historical significance, technical specifications, and operational details. More significantly, oral histories of personal accounts and stories from the former radioman and WW II veteran who served aboard the USS Drum, as shown in

Figure 10, add a personal and immersive element to the tour and provide a unique perspective on the daily life and experiences of the crew during the war.

4.2. Findings of the User Experience Study

A total of 92 valid questionnaire responses were received. The following sections present the survey results and discussions.

4.2.1. Demographic Background

The survey began by collecting demographic information to understand the respondents’ backgrounds. The first question asked participants if they had used VTs before. Out of 92 respondents, the majority, 68.48% (63 participants), indicated that they had, while 31.52% (29 participants) had not. Data collected from the second question revealed that most respondents were male, comprising 85.87% (79 participants), while 14.13% (13 participants) were female. As shown in

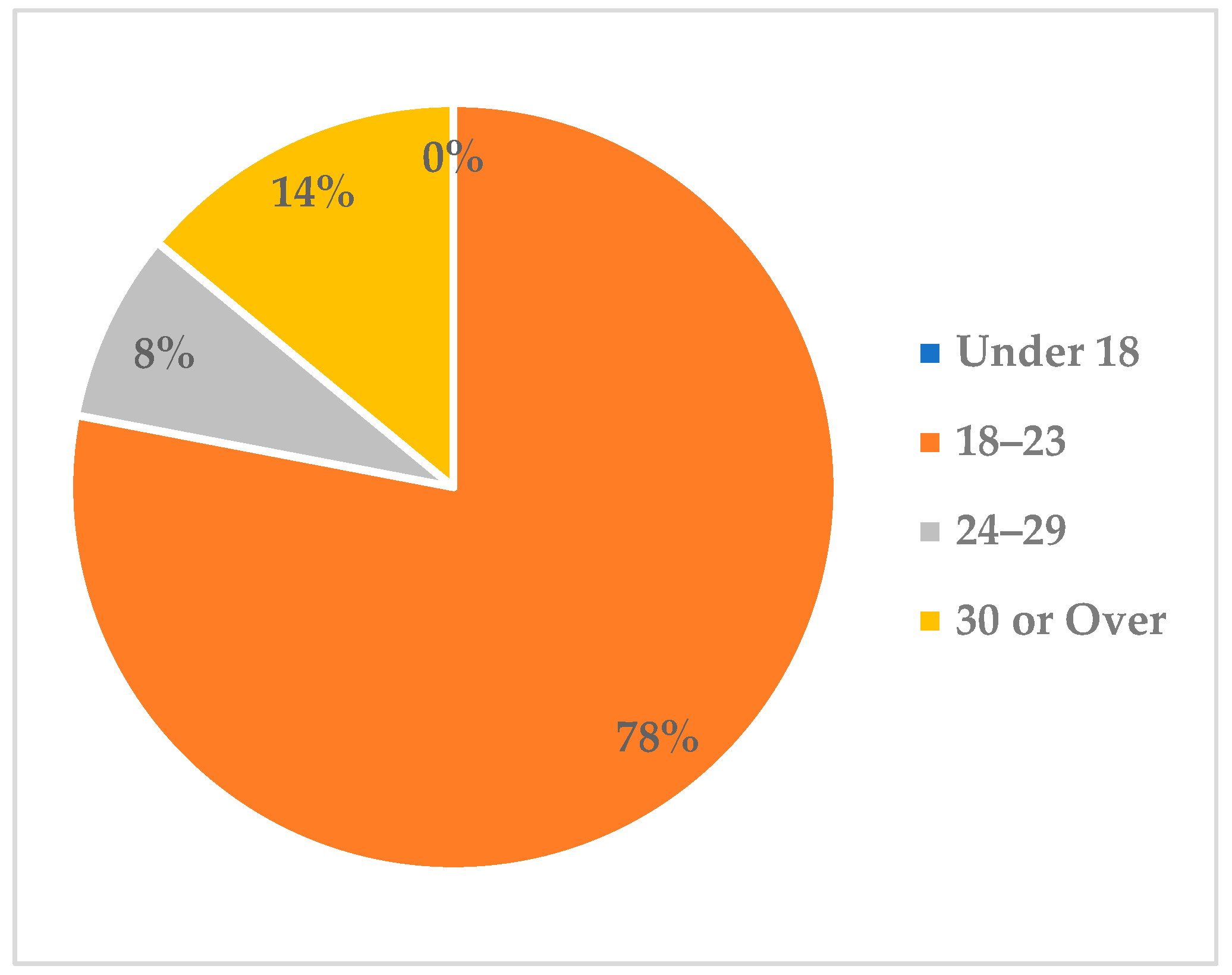

Figure 11, the age distribution indicates that the sample primarily consisted of young adults, with the majority falling within the 18–23 age range. The predominance of young adults and males in the survey sample reflects the typical demographic of students in a construction management program in the USA, who were the primary participants in this study.

4.2.2. Technical Aspects of the Virtual Tour

The next section of the survey included a series of questions designed to assess the technical aspects of the VT. Respondents were asked to rate their agreement with six statements on a scale from one (strongly disagree) to five (strongly agree).

Table 1 presents a summary of their responses.

As illustrated in

Figure 12, the respondents overwhelmingly agreed that the VT’s interface was easy to use, with a mean score of 4.8. Specifically, 81.52% of respondents strongly agreed, and 17.39% somewhat agreed, indicating high usability. The imagery provided was rated as highly vivid, with a mean score of 4.77; 81.52% of respondents strongly agreed and 15.22% somewhat agreed, reflecting the quality of the visual content. Similarly, the detailed nature of the VT imagery received a mean score of 4.77, with 80.43% of respondents strongly agreeing and 17.39% somewhat agreeing, suggesting that respondents found the VT to be visually detailed and informative. Navigation within the VT was also highly rated, with a mean score of 4.71; 72.83% of respondents strongly agreed and 25% somewhat agreed, highlighting the effective navigation design. The YouTube videos linked to the VT were considered informative, receiving a mean score of 4.78; about 81.52% of respondents strongly agreed and 15.22% somewhat agreed, indicating the usefulness of the additional video content. Furthermore, the YouTube videos and other media files linked to the VT were perceived to enhance the tour, with a mean score of 4.82; approximately 82.61% of respondents strongly agreed and 16.30% somewhat agreed, showing that multimedia elements significantly contributed to the overall experience.

Out of 92 respondents, only 11.96% (11 participants) reported experiencing technical issues, while 88.04% (81 participants) did not encounter any problems. Key issues mentioned included problems with YouTube video playback, such as videos not enlarging to full screen, stopping if the mouse moved off them, and requiring restarts. Additionally, a few respondents faced challenges with navigation, such as difficulty viewing historic photos, sporadic floor plan views, and initial confusion when moving around the tour. A summary of the technical difficulties reported by the respondents is listed in

Table 2.

4.2.3. User Experience of the Virtual Tour

The results of the next section of the survey provide a comprehensive overview of the user experience of the USS Drum VT. The data reveal that the tour was generally well-received, with high ratings across several dimensions, including visual quality, immersion, enjoyment, and informational value.

Table 3 includes a summary of the responses.

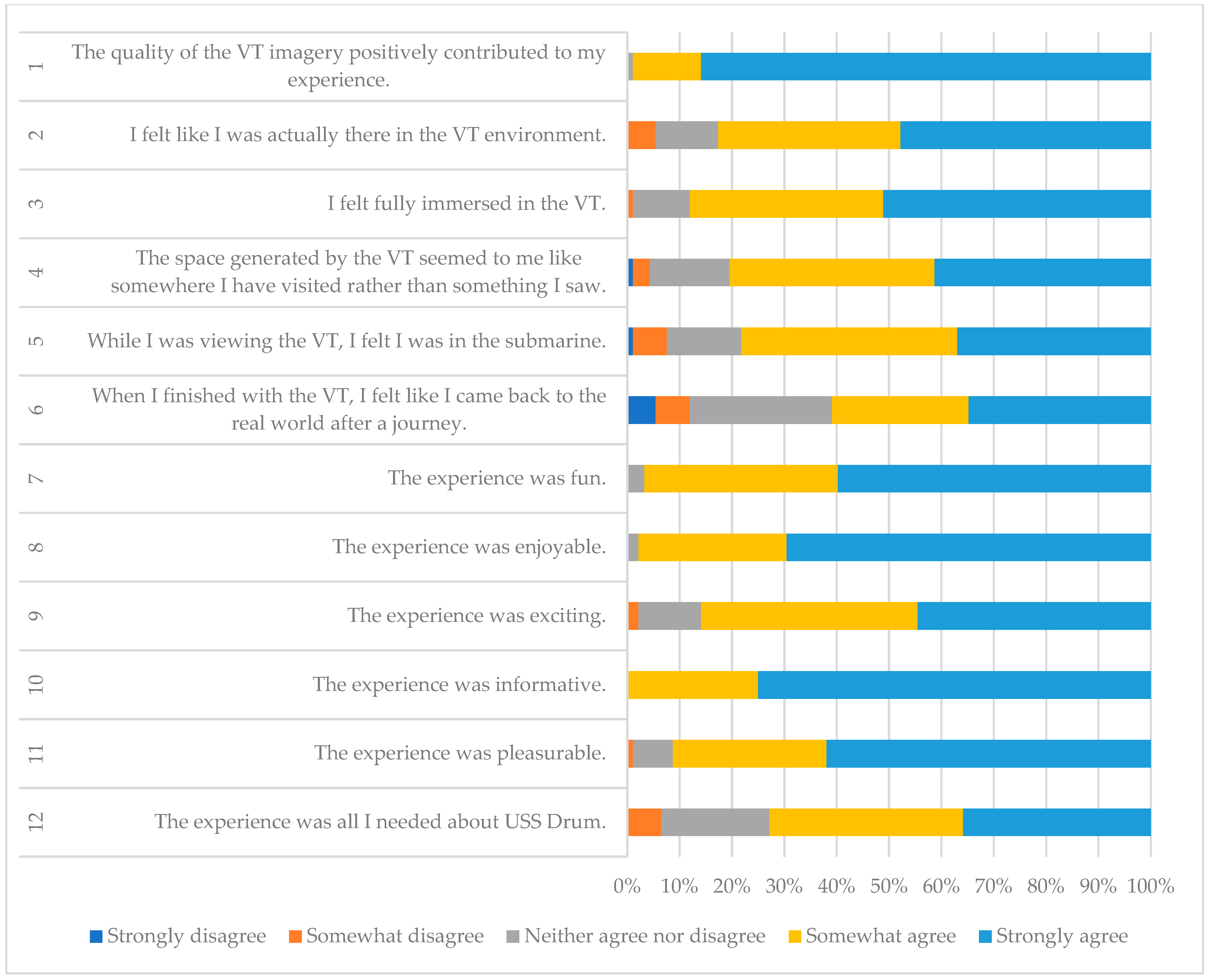

As shown in

Figure 13, the quality of the VT imagery was highly appreciated by respondents, with a mean score of 4.84; 85.87% strongly agreed that it positively contributed to their experience, and 13.04% somewhat agreed, indicating significant visual fidelity. The tour also created a strong sense of immersion, with statements like “I felt like I was actually there in the VT environment” and “I felt fully immersed in the VT” receiving mean scores of 4.25 and 4.38, respectively. This suggests that the VT successfully engaged users by providing a realistic environment. Additionally, the VT was effective in making users feel like they were in a real, physical space, as indicated by a mean score of 4.16 for the statement about the space feeling like “somewhere I have visited” rather than “something I saw”. The tour’s ability to provide an entertaining and enjoyable experience was also reflected in high scores for fun (4.56) and enjoyment (4.67). Furthermore, the VT was considered highly informative, with a mean score of 4.75, showing its effectiveness in conveying information about the USS Drum. Overall satisfaction was high, with the statement “The experience was all I needed about USS Drum” receiving a mean score of 4.02, indicating that most users felt the VT provided a comprehensive and satisfactory overview of the submarine.

4.2.4. User Experience Comparison Study: Virtual Tour vs. In-Person Visit

The research also included studies of (1) the perceptions of the VT users who had physically visited the USS Drum Museum in the past and (2) the impact of the VT on raising the interest of those who had not visited the museum in person.

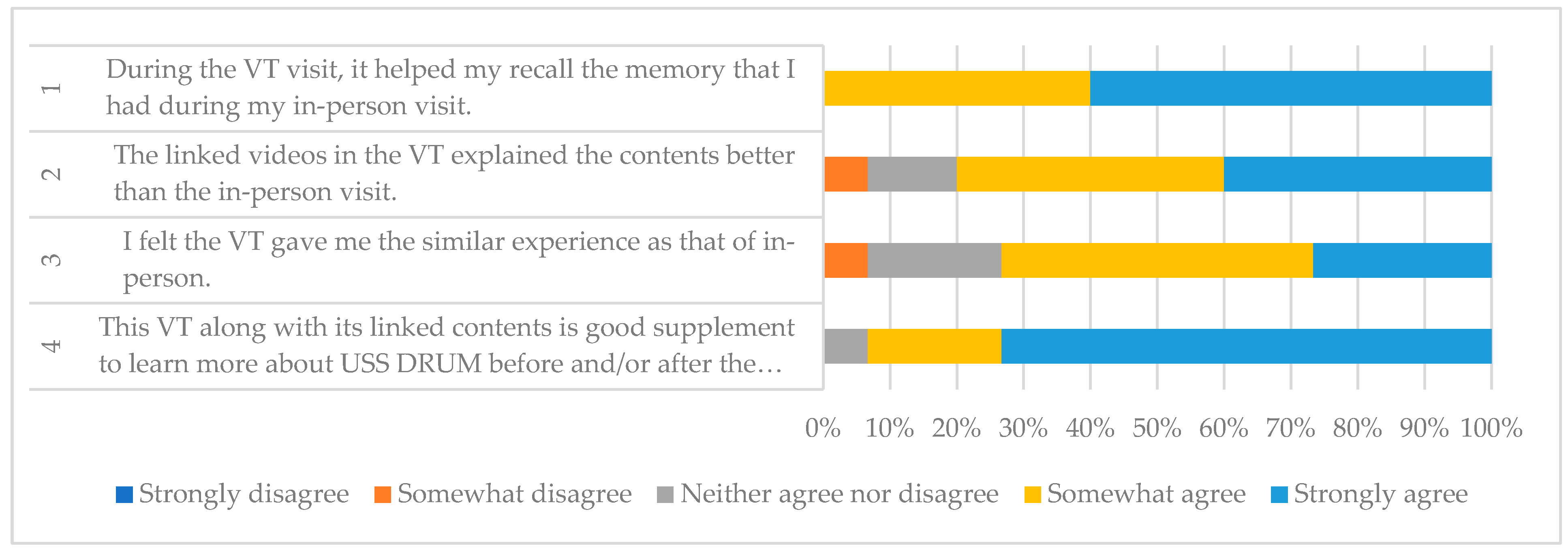

Only 16.30% (15) of the 92 respondents had previously visited the submarine, with most visits occurring more than five years ago. Among these respondents, as reflected in

Table 4 and shown in

Figure 14, the VT helped recall memories of the in-person visit, with a mean score of 4.6. They found the linked video narratives explained the content better than the in-person visit (mean score of 4.13) and felt that the VT provided a similar experience to being there in person (mean score of 3.93). Additionally, the VT was seen as a valuable supplement for learning more about USS Drum, both before and after an actual visit, with a mean score of 4.67.

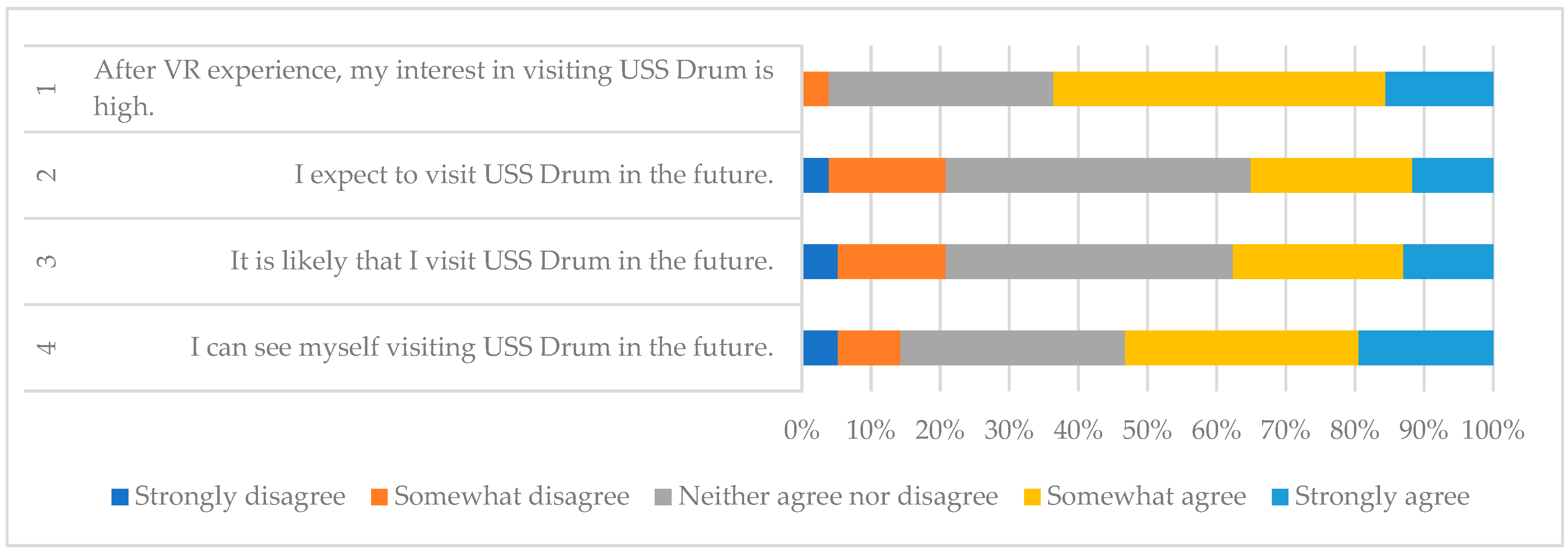

For the 77 respondents who had never visited USS Drum in person, as shown in

Table 5 and

Figure 15, the VT significantly increased their interest in visiting the submarine, with mean scores of 3.75 for increased interest. Furthermore, the VT positively influenced their intention to visit, as reflected in the mean scores of 3.22 for expecting to visit, 3.25 for the likelihood of visiting, and 3.53 for seeing themselves visiting in the near future. Overall, the VT effectively enhanced interest and intention to visit the USS Drum among those who had not experienced an in-person visit.

4.2.5. Respondents’ Comments

The survey also included an open-ended question at the end to collect general comments. Most users noted the overall high quality and proficiency of the VT, and many were impressed by the technology and detailed execution. Many respondents praised the VT in the following aspects:

High educational value and ease of use;

Detailed and smooth interface;

Excellent tool for learning about the USS Drum;

Valuable supplement to an actual visit;

Fun, enjoyable, and informative;

High-quality visuals and seamless transitions.

Many respondents specifically mentioned the oral histories included in the VT through the YouTube videos. Positive feedback highlighted the informative nature of the videos and their contribution to the overall experience. The respondents made positive statements about the VT, such as, “I really enjoyed the WW II crew member’s videos where he discussed his experience”. “The linked videos were an awesome addition”, added another respondent. Another visitor addressed the relevance and impact of the oral history videos, saying: “The videos helped in detailing actual soldiers’ memories of the Drum that can not be replicated”.

Technical difficulties and issues were also mentioned, such as choppy navigation causing motion sickness, getting stuck in corners, challenges in rotating the screen, or problems with video playback. Some users found the floor plan view to be sporadic and hard to interpret, and the need for additional documentation. Some users suggested adding PDFs of important documentation with historical facts on the walls for easier reading. Despite these issues, most users found the VT easy to navigate and appreciated the smooth transitions between the different sections of the submarine.

5. Conclusions and Recommendations for Future Research

This study set out to develop and evaluate an immersive 360-degree virtual tour (VT) of the USS Drum Submarine Museum, incorporating oral histories to enhance the accessibility and visitor experience. Utilizing Matterport technology, the VT provided a detailed and interactive digital representation of the WW II submarine, addressing the challenges of physical access and enhancing engagement through multimedia elements.

The results from the user experience study carried out through a questionnaire survey indicate that the VT was highly effective in providing an immersive and informative experience. Respondents overwhelmingly appreciated the quality of the VT imagery, reporting high levels of satisfaction with the visual fidelity and the detailed representation of the submarine. Most of the respondents found the VT easy to navigate, with high usability scores, though some reported minor technical difficulties, such as video playback and navigation issues. The VT also demonstrated significant effectiveness in engaging users and enhancing their understanding of the USS Drum. The high ratings for visual quality, immersion, and informational value highlight the VT’s ability to provide a compelling alternative to physical visits.

The use of oral histories through embedded videos in the tour contributed notably to creating a deeper connection with the heritage site, as personal stories and experiences from a World War II veteran brought a human element to the historical narrative. These video narratives provided context and emotional depth, making the historical content more relatable and memorable. They proved to be a significant enhancement for the visitor experience, offering deeper insights and personal connections to the submarine’s history. This approach highlights the potential of combining VR technology with oral histories to create immersive educational tools that preserve and promote cultural heritage.

The research findings reflected the primary strength of the VT, which lies in its ability to make this maritime heritage site accessible to a broader audience, including those with mobility challenges or those who cannot visit in person. However, the VT also has limitations, including occasional technical issues with video playback and navigation. Additionally, the experience cannot fully replicate the physical presence and scale of the submarine, which some users noted.

Future research should focus on addressing the technical limitations identified in this study, such as improving video playback and navigation features. There is also potential to expand the use of VR and VT technologies in other historical tours, exploring how these tools can be used to document and share a wider range of heritage sites. Additionally, further studies could investigate the long-term impact of VTs on users’ historical knowledge retention and their effectiveness in educational settings. Furthermore, while this study provided valuable insights into the effectiveness of VTs, the long-term impact on physical museum visits remains to be seen. Longitudinal studies can be carried out to assess the lasting effects of VTs on physical museum attendance.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization and methodology, J.L., D.S.W. and J.S.K.; validation, J.L. and D.S.W.; formal analysis, J.L. and D.S.W.; investigation, D.S.W. and J.L.; data curation, J.L., D.S.W. and J.S.K.; writing—original draft preparation, J.L.; writing—review and editing, J.L. and D.S.W.; visualization, J.L. and D.S.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available upon request from the corresponding authors. Due to the sensitive nature of the data and their file size, access to the data will be granted on a case-by-case basis and may require a data use agreement to be signed.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 360° Virtual Tours. 2024. Available online: https://en.chateauversailles.fr/discover/resources/360deg-virtual-tours (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Boas, Yuri Antonio Gonçalves Vilas. 2013. Overview of Virtual Reality Technologies. Paper presented at Interactive Multimedia Conference 2013, Bogotá, Colombia, August 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Bozzelli, Gguido, Antonio Raia, Stefano Ricciardi, Maurizio De Nino, Nicola Barile, Marco Perrella, Marco Tramontano, Alfosina Pagano, and Augusto Palombini. 2019. An Integrated VR/AR Framework for User-Centric Interactive Experience of Cultural Heritage: The ArkaeVision Project. Digital Applications in Archaeology and Cultural Heritage 15: e00124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, Dimitrios, Alexis Papathanassis, and Maria Vafeidou. 2021. Smart Cruising: Smart Technology Applications and Their Diffusion in Cruise Tourism. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Technology 13: 626–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buhalis, Dimitrios, and Eleni Michopoulou. 2011. Information-Enabled Tourism Destination Marketing: Addressing the Accessibility Market. Current Issues in Tourism 14: 145–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burke, Verity, Dolly Jørgensen, and Finn Arne Jørgensen. 2020. Museums at Home: Digital Initiatives in Response to COVID-19. Norsk Museumstidsskrift 6: 117–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campitiello, Lucia, Aldo Caldarelli, Michele Domenico Todino, Pio Alfredo Di Tore, Stefano Di Tore, and Amelia Lecce. 2022. Maximising Accessibility in Museum Education through Virtual Reality: An Inclusive Perspective. Giornale Italiano Di Educazione Alla Salute, Sport e Didattica Inclusiva 6: 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Cardona, Hector, Carlos Lara-Alvarez, Ezra Parra, and Klinge Villalba-Condori. 2023. Virtual Tours to Facilities for Educational Purposes: A Review. TEM Journal 12: 1725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Churchill, Elizabeth, David Snowdon, and Alan Munro. 2012. Collaborative Virtual Environments: Digital Places and Spaces for Interaction. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. [Google Scholar]

- Clerkin, Caitlin Chien, and Bradley Taylor. 2021. Online Encounters with Museum Antiquities. American Journal of Archaeology 125: 165–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cruz-Neira, Carolina, Daniel J. Sandin, Thomas A. DeFanti, Robert V. Kenyon, and John C. Hart. 1992. The CAVE: Audio Visual Experience Automatic Virtual Environment. Communications of the ACM 35: 64–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Freitas, Sara, Genaro Rebolledo-Mendez, Fotis Liarokapis, George Magoulas, and Alexandra Poulovassilis. 2010. Learning as Immersive Experiences: Using the Four-Dimensional Framework for Designing and Evaluating Immersive Learning Experiences in a Virtual World. British Journal of Educational Technology 41: 69–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Said, Osman, and Heba Aziz. 2022. Virtual Tours a Means to an End: An Analysis of Virtual Tours’ Role in Tourism Recovery Post COVID-19. Journal of Travel Research 61: 528–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Explore Hood Museum Exhibitions through 3D Virtual Tours. n.d. Available online: https://hoodmuseum.dartmouth.edu/news/2022/10/explore-hood-museum-exhibitions-through-3d-virtual-tours (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Fabris, Christian Pierce, Joseph Alexander Rathner, Angelina Yin Fong, and Charles Philip Sevigny. 2019. Virtual Reality in Higher Education. International Journal of Innovation in Science and Mathematics Education 27: 69–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fabroyir, Hadziq, Wei-Chung Teng, and Yen-Chun Lin. 2014. An Immersive and Interactive Map Touring System Based on Traveler Conceptual Models. IEICE Transactions on Information and Systems 97: 1983–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Flavián, Carlos, Sergio Ibáñez-Sánchez, and Carlos Orús. 2021. Impacts of Technological Embodiment through Virtual Reality on Potential Guests’ Emotions and Engagement. Journal of Hospitality Marketing & Management 30: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Foo, C. P., C. W. Wong, Y. H. Ng, and R. Jacosalem. 2023. Exploring Digital Documentation for Shophouses in Singapore. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 48: 579–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fromm, Jennifer, Jaziar Radianti, Charlotte Wehking, Stefan Stieglitz, Tim A. Majchrzak, and Jan vom Brocke. 2021. More than Experience?—On the Unique Opportunities of Virtual Reality to Afford a Holistic Experiential Learning Cycle. The Internet and Higher Education 50: 100804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garau, Chiara, and Emiliano Ilardi. 2014. The “Non-Places” Meet the “Places:” Virtual Tours on Smartphones for the Enhancement of Cultural Heritage. Journal of Urban Technology 21: 79–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaugne, Ronan, Myrsini Samaroudi, Théophane Nicolas, Jean-Baptiste Barreau, Laurent Garnier, Karina Rodriguez Echavarria, and Valérie Gouranton. 2018. Virtual Reality (VR) Interactions with Multiple Interpretations of Archaeological Artefacts. Paper presented at EG GCH 2018—16th EUROGRAPHICS Workshop on Graphics and Cultural Heritage, Vienna, Austria, November 12–15; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Gutiérrez, Mario, Frédéric Vexo, and Daniel Thalmann. 2008. Stepping into Virtual Reality. Berlin: Springer Science & Business Media. ISBN 978-1-84800-117-6. [Google Scholar]

- Gül, Nurcan, and Sevilay Erk. 2021. Naval Museum Spaces a Study on Accessibility and Visibility Based on the Relationship between the Sea and Land. Journal of Design for Resilience in Architecture and Planning 2: 366–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Dai-In Danny, Jessika Weber, Marcel Bastiaansen, Ondrej Mitas, and Xander Lub. 2019. Virtual and Augmented Reality Technologies to Enhance the Visitor Experience in Cultural Tourism. In Augmented Reality and Virtual Reality: The Power of AR and VR for Business. Edited by M. Claudia tom Dieck and Timothy Jung. Cham: Springer International Publishing, pp. 113–28. ISBN 978-3-030-06246-0. [Google Scholar]

- Hausmann, Andrea, Lena Weuster, and Neda Nouri-Fritsche. 2015. Making Heritage Accessible: Usage and Benefits of Web-Based Applications in Cultural Tourism. International Journal of Cultural and Digital Tourism 2: 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Home—USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park. n.d. Available online: https://www.ussalabama.com/ (accessed on 28 June 2024).

- Huang, Xiaohong, Xiangmin Guo, and Tiantian Lo. 2021. Visualization of Ancient Buildings: Virtual Simulation for Online Historical Architecture Learning. Paper presented at 2021 IEEE International Conference on Educational Technology, ICET 2021, Beijing, China, June 18–20; Interlaken: Institute of Electrical and Electronics Engineers Inc., pp. 162–66. [Google Scholar]

- Kask, Sergey. 2018. Virtual Reality in Support of Sustainable Tourism. Experiences from Eastern Europe. Ph.D. thesis, Eesti Maaülikool, Tartu, Estonia. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, Jeffrey, and Tom Leathem. 2018. Virtual Reality as a Standard in the Construction Management Curriculum. Paper presented at International Conference on Construction Futures, Wolverhampton, UK, December 11. [Google Scholar]

- Kiy, Marina. 2019. The Virtual Library Tours. Nauchnye I Tekhnicheskie Biblioteki-Scientific and Technical Libraries 7: 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuksa, Iryna, and Mark Childs. 2014. Making Sense of Space: The Design and Experience of Virtual Spaces as a Tool for Communication. Amsterdam: Elsevier. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Junshan, Danielle S. Willkens, and Graham Foreman. 2022. An introduction to technological tools and process of Heritage Building Information Modeling (HBIM). Paper presented at EGE Revista de Expresión Gráfica en la Edificación, Valencia, Spain, June 30; pp. 50–65. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Junshan, Danielle S. Willkens, Concepcion López, Luis Cortés-Meseguer, Jorge Luis García-Valldecabres, Pablo A. Escudero, and Shadi Alathamneh. 2023a. Comparative Analysis of Point Clouds Acquired from a TLS Survey and a 3D Virtual Tour for HBIM Development. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 48: 959–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junshan, Gorham Bird, Danielle S. Willkens, Richard A. Burt, and Hunter McGonagill. 2023b. Preserving the History of African American Education: Digital Documentation of Rosenwald Schools—A Case Study on the Tankersley School in Hope Hull, Alabama, USA. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 48: 951–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Junshan, Graham Foreman, Anoop Sattineni, and Botao Li. 2023c. Integrating Stakeholders’ Priorities into Level of Development Supplemental Guidelines for HBIM Implementation. Buildings 13: 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luz, Filipe C., Jorge Oliveira, and V. Flores. 2020. Virtual Museum to Promote Accessibility to Art and Cultural Heritage: Quantitative Study on User Experience within a Virtual Reality Task. Paper presented at 13th ICDVRAT with ITAG, Serpa, Portugal, September 9–11. [Google Scholar]

- Mantovani, Fabrizia. 2003. 12 VR Learning: Potential and Challenges for the Use of 3D. In Towards CyberPsychology: Mind, Cognitions and Society in the Internet Age, 3rd ed. Amsterdam: IOS Press, pp. 207–26. [Google Scholar]

- Matterport. 2024. Matterport Capture, Share, and Collaborate the Built World in Immersive 3D. Available online: https://matterport.com/ (accessed on 20 May 2023).

- McLean, Graeme, and Jennifer B. Barhorst. 2022. Living the Experience before You Go … but Did It Meet Expectations? The Role of Virtual Reality during Hotel Bookings. Journal of Travel Research 61: 1233–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montusiewicz, Jezzy, Marcin Barszcz, Stanislaw Skulimowski, Rahim Kayumov, and Muhammad Buzrukov. 2018. The Concept of Low-Cost Interactive and Gamified Virtual Exposition. Paper presented at 12th International Technology, Education and Development Conference (INTED), Valencia, Spain, March 5–7; pp. 353–63. [Google Scholar]

- Online Tour & Museum—Battleship USS Iowa Museum. 2020. Available online: https://pacificbattleship.com/museum_visit/virtual_tours_videos/virtual-tour-content/ (accessed on 27 August 2024).

- Online Tours—Enjoy the Louvre at Home! n.d. Available online: https://www.louvre.fr/en/online-tours (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Paladini, A., A. Dhanda, M. Reina Ortiz, A. Weigert, E. Nofal, A. Min, M. Gyi, S. Su, K. Van Balen, and M. Santana Quintero. 2019. Impact of Virtual Reality Experience on Accessibility of Cultural Heritage. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences XLII-2-W11: 929–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez, Emiliano, M. J. Merchan, S. Salamanca, and P. Merchan. 2019. Virtual Reality to Allow Wheelchair Users Touring Complex Archaeological Sites in A Realistic Manner. Towards Their Actual Social Integration. Paper presented at 8th International Workshop 3D-ARCH: 3D Virtual Reconstruction and Visualization of Complex Architectures, Bergamo, Italy, February 6–8, vol. 42, pp. 597–604. [Google Scholar]

- Pieters, Marnix. 2017. The Social and Economic Benefits of Marine and Maritime Cultural Heritage: Towards Greater Accessibility and Effective Management. International Journal of Nautical Archaeology 46: 223–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Priolo, Ferimar R., Reycel Joy B. Mediavillo, Alexandra Nichole D. C. Austria, Aubrey Gail S. Delos Angeles, Ma. Corazon G. Fernando, and Reginald S. Cheng. 2017. Virtual Heritage Tour: A 3D Interactive Virtual Tour Musealisation Application. Paper presented at 3RD International Conference on Communication and Information Processing (ICCIP 2017), Tokyo, Japan, November 24–26; pp. 190–95. [Google Scholar]

- Puig, Anna, Inmaculada Rodríguez, Josep Ll. Arcos, Juan A. Rodríguez-Aguilar, Sergi Cebrián, Anton Bogdanovych, Núria Morera, Antoni Palomo, and Raquel Piqué. 2020. Lessons Learned from Supplementing Archaeological Museum Exhibitions with Virtual Reality. Virtual Reality 24: 343–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulcrano, Margherita, Simona Scandurra, Gianluca Minin, and Antonella di Luggo. 2019. 3D Cameras Acquisitions for the Documentation of Cultural Heritage. The International Archives of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences 42: 639–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Resta, Giuseppe, Fabiana Dicuonzo, Evrim Karacan, and Domenico Pastore. 2021. The Impact of Virtual Tours on Museum Exhibitions after the Onset of COVID-19 Restrictions: Visitor Engagement and Long-Term Perspectives. SCIRES-IT-SCIentific RESearch and Information Technology 11: 151–66. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-García, María Eugenia, Fernando Criado-García, José Antonio Camúñez-Ruíz, and María Casado-Pérez. 2021. Accessibility to Cultural Tourism: The Case of the Major Museums in the City of Seville. Sustainability 13: 3432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roussou, Maria. 2002. Virtual Heritage: From the Research Lab to the Broad Public. Bar International Series 1075: 93–100. [Google Scholar]

- Sann, Raksmey, Pakkapol Luecha, and Rawisara Rueangchaithanakun. 2023. The Effects of Virtual Reality Travel on Satisfaction and Visiting Intention Utilizing an Extended Stimulus-Organism-Response Theory: Perspectives from Thai Tourists. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Insights. ahead-of-print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- SmartView Media. 2021. A Look At Sydney’s Popular Landmarks through Matterport Virtual Tours|SmartView Media-Matterport 3D Virtual Tours. Available online: https://smartviewmedia.com.au/blogs/a-look-at-sydneys-popular-landmarks-through-matterport-virtual-tours/ (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Sobota, Branislav, Štefan Korečko, Ladislav Jacho, P. Pastornický, Marián Hudák, and Martin Sivý. 2017. Virtual-Reality Technologies and Smart Environments in the Process of Disabled People Education. Paper presented at 2017 15th International Conference on Emerging eLearning Technologies and Applications (ICETA), Stary Smokovec, Slovakia, October 26–27; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Sofaer, Joanna, Ben Davenport, Marie Louise Stig Sørensen, Eirini Gallou, and David Uzzell. 2021. Heritage Sites, Value and Wellbeing: Learning from the COVID-19 Pandemic in England. International Journal of Heritage Studies 27: 1117–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spennemann, Dirk H. R. 2021. COVID-19 on the Ground: Managing the Heritage Sites of a Pandemic. Heritage 4: 2140–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stylianidis, Efstratios. 2020. Photogrammetric Survey for the Recording and Documentation of Historic Buildings. Springer Tracts in Civil Engineering. Cham: Springer International Publishing. ISBN 978-3-030-47309-9. [Google Scholar]

- Tolvanen, Sanna. 2023. Inclusion of People on the Autism Spectrum: Accessible Virtual Tourism Services. Bachelor thesis, Laurea University of Applied Sciences, Vantaa, Finland. [Google Scholar]

- TOTI SUBMARINE VR EXPERIENCE. n.d. Available online: https://www.museoscienza.org/en/toti-submarine-vr-experience (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Toti SubmarineVR Experience. n.d. Available online: https://unimersiv.com/review/toti-submarinevr-experience/ (accessed on 2 August 2024).

- Tylko, John. 2023. Simulating Apollo: Flight Simulation Technology 1945–1975. Doctoral thesis, Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Cambridge, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- USS Drum—USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park. n.d. Available online: https://www.ussalabama.com/explore/uss-drum/ (accessed on 24 May 2022).

- Virtual Reality Tours. n.d. Available online: https://artsandculture.google.com/project/virtual-tours (accessed on 27 June 2024).

- Wang, Jie, Gabriella Medvegy, and Jianjun Hou. 2023. The Application of Digital Technology in the Protection of Architectural Cultural Heritage. Paper presented at ICEB 2023 Proceedings, Chiayi, Taiwan, October 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Yung, Ryan, Catheryn Khoo-Lattimore, and Leigh Ellen Potter. 2021. VR the World: Experimenting with Emotion and Presence for Tourism Marketing. Journal of Hospitality and Tourism Management 46: 160–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Cheng. 2013. The Moon Experience: Designing Participatory Immersive Environments for Experiential Learning. Master’s thesis, The Ohio State University, Columbus, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

Figure 1.

The exterior of the USS Drum Submarine Museum in Mobile, Alabama, USA.

Figure 1.

The exterior of the USS Drum Submarine Museum in Mobile, Alabama, USA.

Figure 2.

Comparison of immersion, presence, and telepresence (I.P.T.) in various form factors with today’s VR technology (

Kim and Leathem 2018).

Figure 2.

Comparison of immersion, presence, and telepresence (I.P.T.) in various form factors with today’s VR technology (

Kim and Leathem 2018).

Figure 3.

The USS Iowa Battleship virtual tour (

Online Tour & Museum—Battleship USS Iowa Museum 2020). (

a) Front page of the virtual tour showing the exterior of the bow of the battleship and the navigation panel of the tour. (

b) A panoramic view of the main deck level, showing a navigation arrow and the level plan. (

c) The interior of the bridge, showing a navigation arrow and the level plan.

Figure 3.

The USS Iowa Battleship virtual tour (

Online Tour & Museum—Battleship USS Iowa Museum 2020). (

a) Front page of the virtual tour showing the exterior of the bow of the battleship and the navigation panel of the tour. (

b) A panoramic view of the main deck level, showing a navigation arrow and the level plan. (

c) The interior of the bridge, showing a navigation arrow and the level plan.

Figure 5.

The USS Drum Submarine Museum. (a) The main exhibitions of the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, Alabama. (b) The bow of the submarine. (c) The main deck of the submarine. (d) The narrow passage inside. (e) The camped aft torpedo room.

Figure 5.

The USS Drum Submarine Museum. (a) The main exhibitions of the USS Alabama Battleship Memorial Park in Mobile, Alabama. (b) The bow of the submarine. (c) The main deck of the submarine. (d) The narrow passage inside. (e) The camped aft torpedo room.

Figure 6.

The workflow utilized to develop the virtual tour of the USS Drum.

Figure 6.

The workflow utilized to develop the virtual tour of the USS Drum.

Figure 7.

Capture of the virtual tour. (a) A PRO-2 camera capturing the bow torpedo room. (b) Stationary setups displayed on an iPad. (c) The USS Drum curator being filmed while explaining an element on the main deck.

Figure 7.

Capture of the virtual tour. (a) A PRO-2 camera capturing the bow torpedo room. (b) Stationary setups displayed on an iPad. (c) The USS Drum curator being filmed while explaining an element on the main deck.

Figure 8.

Detailed and immersive imagery and navigation of the virtual tour of USS Drum. (a) Exterior view on the main deck. (b) Inside the front torpedo room.

Figure 8.

Detailed and immersive imagery and navigation of the virtual tour of USS Drum. (a) Exterior view on the main deck. (b) Inside the front torpedo room.

Figure 9.

A 3D perspective view and plan views of the virtual tour. (a) A “dollhouse” view. (b) Main deck floor plan. (c) Compartment floor plan. Note: Green circles (or “tags”) link to short films featured by the USS Drum’s curator explaining the historical significance, technical specifications, and operational details of the submarine; purple circles link to short films of a WW II veteran and offer his personal accounts and stories aboard the USS Drum.

Figure 9.

A 3D perspective view and plan views of the virtual tour. (a) A “dollhouse” view. (b) Main deck floor plan. (c) Compartment floor plan. Note: Green circles (or “tags”) link to short films featured by the USS Drum’s curator explaining the historical significance, technical specifications, and operational details of the submarine; purple circles link to short films of a WW II veteran and offer his personal accounts and stories aboard the USS Drum.

Figure 10.

Oral histories are integrated into the virtual tour.

Figure 10.

Oral histories are integrated into the virtual tour.

Figure 11.

Survey respondent age distribution.

Figure 11.

Survey respondent age distribution.

Figure 12.

Survey responses on technical aspects of the VT.

Figure 12.

Survey responses on technical aspects of the VT.

Figure 13.

Survey responses on user experience of the VT.

Figure 13.

Survey responses on user experience of the VT.

Figure 14.

Comparison of VT experience vs. in-person visit.

Figure 14.

Comparison of VT experience vs. in-person visit.

Figure 15.

Respondents’ interest in visiting the USS Drum after the VT experience.

Figure 15.

Respondents’ interest in visiting the USS Drum after the VT experience.

Table 1.

Summary of survey responses on technical aspects of the USS Drum virtual tour.

Table 1.

Summary of survey responses on technical aspects of the USS Drum virtual tour.

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Std Deviation | Variance | Total Count |

|---|

| 1. The interface of the VT was easy to use. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 17.39% (16) | 81.52% (75) | 4.80 | 0.42 | 0.18 | 92 |

| 2. The imagery provided by the VT was highly vivid. | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 2.17% (2) | 15.22% (14) | 81.52% (75) | 4.77 | 0.53 | 0.28 | 92 |

| 3. The imagery provided by the VT was highly detailed. | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 1.09% (1) | 17.39% (16) | 80.43% (74) | 4.77 | 0.51 | 0.26 | 92 |

| 4. I felt like I could navigate around among the objects in the VT. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 2.17% (2) | 25.00% (23) | 72.83% (67) | 4.71 | 0.50 | 0.25 | 92 |

| 5. The YouTube videos linked to the VT were informative. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 3.26% (3) | 15.22% (14) | 81.52% (75) | 4.78 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 92 |

| 6. The YouTube videos and other media files linked to the VT enhanced the tour. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 16.30% (15) | 82.61% (76) | 4.82 | 0.42 | 0.17 | 92 |

Table 2.

Summary of technical difficulties reported by the respondents.

Table 2.

Summary of technical difficulties reported by the respondents.

| Category | Issue Description | Number of Respondents |

|---|

| Video Playback Issues | YouTube videos not enlarging to full screen | 4 |

| YouTube videos stopping if the mouse moved off them | 3 |

| YouTube videos disappearing when clicked, requiring a restart | 2 |

| YouTube links not expanding properly | 2 |

| Video Centering and Stability Issues | Videos closing when trying to open in full screen if the mouse was moved off the video | 3 |

| Videos starting off-center, making them difficult to watch | 2 |

| Videos cutting in and out and then stopping intermittently | 2 |

| Multimedia and Navigation Issues | Moving around the virtual tour was initially confusing and took time to get used to | 4 |

| Loading inside the ship, making it difficult to get bearings and navigate | 3 |

| Historic photo near the torpedo room not viewable, only showing a small icon indicating an image | 2 |

| Clicking on the pictures of soldiers on the sub causing computer to freeze, requiring a restart | 2 |

| Floor plan view of the boat appearing sporadic and hard to interpret | 2 |

| Not able to look underneath, only showing a blurry circle | 1 |

Table 3.

Summary of survey responses on user experience of the USS Drum Virtual Tour.

Table 3.

Summary of survey responses on user experience of the USS Drum Virtual Tour.

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Std Deviation | Variance | Total Count |

|---|

| 1. The quality of the VT imagery positively contributed to my experience. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 13.04% (12) | 85.87% (79) | 4.84 | 0.43 | 0.19 | 92 |

| 2. I felt like I was actually there in the VT environment. | 0.00% (0) | 5.43% (5) | 11.96% (11) | 34.78% (32) | 47.83% (44) | 4.25 | 0.90 | 0.81 | 92 |

| 3. I felt fully immersed in the VT. | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 10.87% (10) | 36.96% (34) | 51.09% (47) | 4.38 | 0.77 | 0.60 | 92 |

| 4. The space generated by the VT seemed to me like “somewhere I have visited” rather than “something I saw”. | 1.09% (1) | 3.26% (3) | 15.22% (14) | 39.13% (36) | 41.30% (38) | 4.16 | 0.94 | 0.88 | 92 |

| 5. While I was viewing the VT, I felt I was in the submarine. | 1.09% (1) | 6.52% (6) | 14.13% (13) | 41.30% (38) | 36.96% (34) | 4.06 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 92 |

| 6. When I finished with the VT, I felt like I came back to the “real world” after a journey. | 5.43% (5) | 6.52% (6) | 27.17% (25) | 26.09% (24) | 34.78% (32) | 3.78 | 1.20 | 1.44 | 92 |

| 7. The experience was fun. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 3.26% (3) | 36.96% (34) | 59.78% (55) | 4.56 | 0.59 | 0.35 | 92 |

| 8. The experience was enjoyable. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 2.17% (2) | 28.26% (26) | 69.57% (64) | 4.67 | 0.52 | 0.27 | 92 |

| 9. The experience was exciting. | 0.00% (0) | 2.17% (2) | 11.96% (11) | 41.30% (38) | 44.57% (41) | 4.28 | 0.82 | 0.67 | 92 |

| 10. The experience was informative. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 25.00% (23) | 75.00% (69) | 4.75 | 0.44 | 0.19 | 92 |

| 11. The experience was pleasurable. | 0.00% (0) | 1.09% (1) | 7.61% (7) | 29.35% (27) | 61.96% (57) | 4.52 | 0.72 | 0.51 | 92 |

| 12. The experience was all I needed about USS Drum. | 0.00% (0) | 6.52% (6) | 20.65% (19) | 36.96% (34) | 35.87% (33) | 4.02 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 92 |

Table 4.

Comparison of VT experience vs. in-person visit.

Table 4.

Comparison of VT experience vs. in-person visit.

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Std Deviation | Variance | Total Count |

|---|

| 1. During the VT visit, it helped my recall the memory that I had during my in-person visit. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 40.00% (6) | 60.00% (9) | 4.6 | 0.49 | 0.24 | 15 |

| 2. The linked videos in the VT explained the contents better than the in-person visit. | 0.00% (0) | 6.67% (1) | 13.33% (2) | 40.00% (6) | 40.00% (6) | 4.13 | 0.88 | 0.78 | 15 |

| 3. I felt the VT gave me the similar experience as that of in-person. | 0.00% (0) | 6.67% (1) | 20.00% (3) | 46.67% (7) | 26.67% (4) | 3.93 | 0.85 | 0.73 | 15 |

| 4. This VT along with its linked contents is a good supplement to learn more about the USS Drum before and/or after the actual visit. | 0.00% (0) | 0.00% (0) | 6.67% (1) | 20.00% (3) | 73.33% (11) | 4.67 | 0.60 | 0.36 | 15 |

Table 5.

Respondents’ interest in visiting USS Drum after VT experience.

Table 5.

Respondents’ interest in visiting USS Drum after VT experience.

| Question | Strongly Disagree | Somewhat Disagree | Neither Agree Nor Disagree | Somewhat Agree | Strongly Agree | Mean | Std Deviation | Variance | Total Count |

|---|

| 1. After VR experience, my interest in visiting the USS Drum is high. | 0.00% (0) | 3.90% (3) | 32.47% (25) | 48.05% (37) | 15.58% (12) | 3.75 | 0.76 | 0.58 | 77 |

| 2. I expect to visit the USS Drum in the future. | 3.90% (3) | 16.88% (13) | 44.16% (34) | 23.38% (18) | 11.69% (9) | 3.22 | 0.99 | 0.98 | 77 |

| 3. It is likely that I visit the USS Drum in the future. | 5.19% (4) | 15.58% (12) | 41.56% (32) | 24.68% (19) | 12.99% (10) | 3.25 | 1.03 | 1.07 | 77 |

| 4. I can see myself visiting the USS Drum in the future. | 5.19% (4) | 9.09% (7) | 32.47% (25) | 33.77% (26) | 19.48% (15) | 3.53 | 1.06 | 1.13 | 77 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).