1. Introduction: Situating Sites, Memory and Monuments in Greek Ethno-Spaces

The period from 1990 (and especially the mid-to-late 1990s) has been one of ‘coming out of Jewish History in Greece’ as Henriette-Rika Benveniste has termed the emergence of a ‘liberating for its actors and usually viewed by others with a kind of astonishment’ set of processes that offered to the public sphere narrations of ‘Greek-Jewish histories’, and, in doing so, brought to the fore contestations of policies and ideologies (

Benveniste 2001). The processes emerged as public, well-attended events and publications, academic and research outputs bringing a spotlight to such ‘Jewish histories’ and along with those, a mixture of discourses and larger meta-narratives.

1 These are very much linked to historiographic trends and situate the contestations at the crossroads of ‘Greek-Jewish’ identities and pasts. They also shed a light on the wider national narratives underpinning national memory and antisemitism. This is because ‘Greek-Jewish’ histories/identities challenge the ongoing crises of multiculturalism and the fragility of ethnonational belonging in Greece. These entanglements with issues of history, memory and identity are also reflected in the way memorials signify particular relationships with the politics of location/s and meaning-making. Such discourses offer ways to understand how the memorialisation of sites grounds the emotive aspect of contested histories (

Cooke 2000).

In this article, critical historical perspectives combine with tracing ‘re-membering’ as a feminist practice in the reassessment of societal values of inclusivity, perceiving the histories of Greek Jewry at the centre of such an endeavour. The ‘coming out’ of such historicity is an outcome of a confluence of reasons. According to Benveniste: ‘By “coming out” of Jewish history, I refer to a process, liberating for its actors and usually viewed by others with a kind of astonishment. This process took place in the 1990’s and brought to the public sphere various agents who attempted to narrate “Jewish histories” or “Greek-Jewish histories”, expressing contested ideologies and policies’.

At the same time, one would question why it is that the 1990s became a fruitful decade for both academic works and academic events on Greek-Jewish history. Again, Benveniste characterises these as ‘hesitant or daring, apologetic or polemic, conciliatory or demanding, introspected or extraverted, implicit or explicit, discourses on Jewish history or on Greek-Jewish history. These discourses belong to larger meta-narratives that underlie either arguments about the past or comprehensive explanations of historical experience and knowledge’. At the same time, Benveniste makes explicit connections to their historical meta-narratives and historiographic trends with a discourse on the ‘duty of memory’ under a spectre of antisemitism; an idyllic coexistence between Jews and Christians; Jewish contributions to Greek welfare; Jews/Judaism as disruptive of the nation; and the conflation of contemporary multicultural with past cosmopolitanism societal contexts, thus leading to anachronism (

Benveniste 2001).

While these are all deeply reflexive historiographic trends, we should not overlook the serendipity of the 1990–91 student protests in Greece and the assassination of the left-wing activist teacher Nikos Temponeras by members of the right-wing governing party youth organisation, as well as other deaths during tear gas attacks by police, coupled with other emerging trends of academic research on the absence of visible traces of Jewish history in Greek urban and peripheral landscapes. During this ‘Greek Spring’ of upheaval and resistance in the academic context, the works that emerged were the outputs by Greece-based and international scholars of Jewish and non-Jewish backgrounds, proclaimed in their own theses, articles and books. Prominently, the 1990s saw a flourishing of Greek-Jewish survivor memoirs emerge; for instance, Erika Kunio-Amariglo’s memoir, titled

From Thessaloniki to Auschwitz and back: Memories of a Survivor from Thessaloniki (1995) was instrumental in introducing the story of the Greek Jews internationally as it was translated into German, English and French, among other languages.

2Other political nudges displacing the focus on the Hellenic ethnocentric self in the 1990s aside from the populist nationalism around the Macedonian issue and the integration of Greece into the European Union and the influx of immigration, interestingly led to more cultural insights into the Hellenic legacy of the past, present and future. Thus, the year 1990 was pivotal in the emergence of the challenging memory of Greek-Jewish Holocaust survivors from within the communities themselves and not just academia, with publishers willing to publish these books and survivors able to write about their experiences. Whether remembrance constituted empowerment and liberation can be gauged, as half a century’s silence gave voice to testimonies. Moreover, it was in 1990 in Thessaloniki that the Society for the Study of Greek Jewry was established and for over a decade a flourishing of symposia and conferences took place at their base and the capital Athens, also adding to further lists of publications in the academic study of the field (

Varon-Vassard 2019). The city of Thessaloniki in northern Greece, as the second largest conurbation in the country, a port city on the Thermaic Gulf of the Aegean Sea, represents in terms of population concentration a representation that has been discussed as a ‘Judeo-Greek culture’ emerging in the 1920s and 1930s reflective of civic, cultural, ethno-religious identity formations. These identities crystallised as ‘Greek Jews’ upon immigration to Israel and the United States (

Fleming 2008). As Katherine Elizabeth Fleming, the author of the first comprehensive ‘Jewish History of Greece’, asserts, in the latter case of the American melting pot, and even so quintessentially in New York City, ‘Greek Jew’ was not an established category. Within a pluri-religious and immigrant religiosity environment, ‘halving’ identities in the usual ‘hyphenated’ sense (e.g., Greek-American) is usually not challenged, whereas Greece-based Greek Jews continue to endure the tensions that legitimising loyalty entails (when Greekness is conflated with Orthodox Christianity) (

Christou 2006).

As the cosmopolitan aura of Thessaloniki waned into becoming a geopolitically decisively Greek city, with clear symbolic markers of identity encapsulated into its culture, religion and language, it might be historiographically challenging to unveil its multicultural persona (

Fleming 2014), but there is no doubt that the core national imagination in the capital of Athens has remained steadfastly one of ethnonational anchoring. So much so that the over three decades of migrant presence and incorporation into Athenian everyday life has done little to erase the spectre of fascist racialisations and instead embrace migrant incorporation as a sign of societal accommodation and not as a threat to Greek national identity (

Christou 2018,

2023;

Christou and Michail 2021;

Tsimouris 2015). This article responds to a programmatic scholarly quest to challenge academic praxis but practise inclusive scholarship for a more comprehensive participation of ‘others’, learning from and through epistemic justice which can be discomforting and challenging, but also, enabling a more radical and international dialogue (

Tolia-Kelly et al. 2020). Thus, the article will interrogate a historical amnesia where Greek Jews do not constitute a strong part of historical memory for Greeks, but also, what is perceived as ‘official’ (legitimate) history. Despite increasing diversification of the population through migration over the past three decades, Greece continues to grapple with xenophobia, racism and antisemitism. One of the first detailed studies of antisemitic attitudes in Greece, ADL’s Global 100 poll was the first detailed study of antisemitic attitudes in Greece; comparing the results in a hundred countries around the world showed that outside of the Middle East, Greece had the highest score with 69% of the population harbouring antisemitic attitudes (

ADL 2019). Other European and independent studies have yielded similar high scores, only slightly diminishing following the introduction of legislative initiatives.

3In this article, critical historical perspectives combine with tracing ‘re-membering’ as a feminist practice in the reassessment of societal values of inclusivity, perceiving the histories of Greek Jewry at the centre of such an endeavour. Furthermore, it is envisaged that memorialisation of Jewish history and Holocaust remembrance can promote eduscapes of justice trickling from pedagogies of hope to connected contemporary communities in Greece (

Freire 1992,

1998). A dialogic reflection (of the historical with the artistic through the feminist lens of activism and resistance) is seen as a pathway to harness the aesthetic context as a heritage of healing and justice by engaging with ‘difficult histories’ in direct collision with racialised acts of silencing them.

In the next section, I trace how narrations of curatorial dissonance and the conflictual aesthetics of monuments are explored in an eclectic methodological framing of affect and ethics. Here, I situate memory and public humanities in Greek historiography as an important new conversation we need to embark on, allowing for the social histories of modern Greece to be ‘reflexive-praxis’. Indeed, it is seen as beneficial to historical research to apply historical reflexivity (

Durepos and Vince 2020). Among its central definitional aspects, ‘historical reflexivity’ as an iterative process of reflection creates narratives of past/present/future practices informed by embodied histories and a sedimentation of narratives over time which become adopted, thus opening the possibility for people to invent historical narratives for change connecting with emotions surfacing though the unsettling practice of reflexivity (

Durepos and Vince 2020). These efforts can be seen as contributions to the new shift in the scholarship of social history of Greece further expanding methods, approaches and tools used in historical research (

Avdela et al. 2018). These renewed foci that give space to emotions and social categories linked with memory have a basis in the important scholarship of influential social and oral historians such as Thompson, Portelli, Passerini and Hobsbawm, to name a few, and can make new compelling contributions to Greek historiography (

Passerini 1987,

2016;

Hobsbawm 1994;

Portelli 1991;

Thompson 1975).

Another key area of contribution is to further contribute to the development of a ‘public humanities paradigm’ in Greece where diverse publics can engage in the humanistic knowledge that ‘Greek-Jewish histories’ can offer to enriching civic, educational and cultural life, thus creating inclusively accessible connected publics of reflexive praxis. This means that by learning and reflecting on such knowledge, more inclusive and connected histories can emerge. In developing connected histories, we can build connected publics, and, by extension address antisemitism through grassroots transformative activity. Moreover, this article contributes to the limited work centring memory in Greek historiography by reconstituting spatialities of Holocaust remembrance as sites for the biographicity of ‘complicated historical, political and aesthetic axes on which Jewish memory is being constructed’ contemporaneously (

Droumpouki 2016). These explorations link well with recent scholarship on the political and discursive framings of the new (publicly announced almost a decade ago, in 2013:

http://holocausteducenter.gr/; accessed on 20 December 2023) Holocaust Museum of Greece (HMG) based in Thessaloniki within an ongoing agenda context of commemoration, reconciliation and antisemitism (

Karasová and Králová 2022).

Following this introduction which has presented the topic and situated the key issues, themes and concepts, the article unfolds along three sections: the next section situates the conceptualisation of the article by framing the central thematic angles of ‘curatorial dissonance and conflictual aesthetics’ while discussing the methodological approach and data pools. The subsequent section on ‘timespaces, memorialisation and the feminist mood’ unpacks the contestations of Holocaust memorials in Greece through a discursive approach to affective ‘re-membering’. Finally, the concluding section offers reflections on how heritage healing is imperative to embedding critical pedagogies as ‘justice eduscapes’ in curricula and policy.

2. Narrating Curatorial Dissonance and Conflictual Aesthetics: Methodologies, Affect and Ethics

When teaching for a number of years a module on ‘Race, Ethnicity and Immigration in the US’ for a summer university international programme hosted in Greece, one of the fieldtrips involved a visit to the Jewish Museum of Greece (JMG, Athens), combined with my related fieldwork and research, which continued after each successive completion of the intensive summer course. In 2008, marking 70 years from the November 1938 Jewish pogroms in Germany, in lieu of International Holocaust Remembrance Day, plans to meet up with Jewish-American friends while we were all conducting different pieces of research in Thessaloniki, and with that year’s theme being ‘imagine, remember, reflect, react’, I embarked on a parallel project that would continue in Athens in 2010, leading up to the 2020 COVID-19 pandemic. The years between 2008 and 2019 included segments of brief fieldwork with disruptions and pauses, marked by periods of caring, loss, grief and mourning in the researcher’s life, frequently navigating the boundaries of re-visiting participants’ discussions as wider traumas and crises eschewed the blurring of living the field in everyday life. Planned fieldwork for the summer of 2022 was cancelled due to an unexpected earlier visit to Greece coinciding with a prolonged period of compassionate leave. Although in many ways, elements of loss and trauma are entangled with this research, the study itself is not designed as research on grief and bereavement. And, while bereavement for the researcher is an ongoing process, the decision not to proceed with new research and instead to draw on past data and personal experiences was one to highlight the ethical issue of preventing secondary distress in participants arising from researcher contact during a period of personal tragic abrupt loss.

Over the last decade, the ‘multisensory ethnographic activity timespaces’ have unfolded in three layered encounters: within temporal and spatial immersive solo visits to Jewish monument locations in Thessaloniki and Athens; during interactive visits with Jewish (and their Jewish or non-Jewish partners) international visitors who were friends or colleagues; and during interactive visits with Greek and diaspora Greek participants who would agree to a ‘walking crafting exposition’ (as a mobile methodological means) in storytelling ‘belonging’ and ‘empathy’. Through multi-sensory immersive practices, in each of these three-layered approaches to a study fragmented by affect and periods of disconnect, I would spend the interim periods away from the field to reflect on the data pools through a processual unfolding of the deep-rooted culture ripples from each dynamic encounter.

The fragmented ethnographic sensibilities were stretched to a questioning of the lived experiences within the contexts of wider local and global issues (primarily the multiple societal and economic crises in Greece; the recurrent instances of xenophobia and antisemitism; the wider populist discourse, etc.) to understand the complexities, possibilities, contradictions, unsettling and re-groundings of the cultural politics surfacing through the study. Depending on the language used during participant dialogic interactions, fieldnotes were compiled in either Greek or English, while conscious decision-making not to use audio or video recording was made following multiple requests by participants to resist the intrusiveness of technology while we connected over our feelings emerging while at memorial sites.

4 In those instances, the moods and affectivities captured following the visits should be seen as fleeting, messy and diluted interactive distilling of affective subjectivities, reflecting mine as much as my participants’ encounters and emotions.

For those participants who were able to engage with a vignette reading prior to our fieldworking walking and talking encounters, there was one choice offered for consistency, the digitised, ‘

Neither Yesterdays Nor Tomorrows:

Vignettes of a Holocaust Childhood’, by

George J. Elbaum (

2010):

https://collections.ushmm.org/search/catalog/bib211120; accessed on 20 December 2023. The use of the vignette followed standard practice in qualitative research on sensitive topics where participants might not feel comfortable discussing their personal situation, actions and beliefs, but through this kind of engagement might feel more at ease to do so (

Barter and Renold 2000;

Hughes and Huby 2004;

Brondani et al. 2008;

Kandemir and Budd 2018;

Törrönen 2018;

Sampson and Johannessen 2020;

McInroy and Beer 2022). The interpretation of the data from those encounters followed the rhythms of a dialogically engaged conversation and, where ‘foregrounding an explicitly articulated theoretical position of dialogicality’, offers the possibility to move through positions without the rigidity of seeing this fluidity as an obstacle to meaning-making (

O’Dell et al. 2012). The use of feminist ethnographic vignettes contributes to recent calls for the development of their methodological attention aligned to the affective turn in boosting their epistemological significance as uniquely valuable (

Bloom-Christen and Grunow 2022).

This contribution draws from a combination of data pools and archival sources to reflect on how Holocaust memorials in Greece provide a platform for historical geographies of contested spaces to enhance knowledge of marginalised narratives and experiences.

5 Such an epistemological platform can engage with the curatorial dissonance and the conflictual aesthetics that monuments trigger with antisemitic discourse of populist, xenophobic and racist proliferation in contemporary Greece. In supporting a solidarity agenda of justice to emerge in heritage and historiographic accounts for new critical public humanities to materialise in Greece, this article calls for a programmatic shift in academic activism informing critical pedagogies and by extension educational policy.

In situating the conceptualisation of the article, I start by framing the central thematic angles of ‘curatorial dissonance and conflictual aesthetics’ while also linking these to the literature on Holocaust memory in Greece.

The recognition of artistic praxis as a source of political efficacy should be problematised in its potential to cross the line of the social towards the political. This would be an act of using art for the service of a common good, and by extension, to unleash its political potential as a field of aesthetics making political interventions through its propensity to have radical potential for political propaganda activism. In other words, to put it simply, the artistic object shifts purpose from a signifier of imagery aesthesis to a vessel of politicisation. This position draws from Oliver Marchart’s new political theory of art and artistic praxis, to accept that simplistically ‘art is political when it is political. It is not when it is not’ (

Marchart 2019).

In this regard, the act and physicality of intervention in the Greek landscape by and through the public visual display of a Holocaust memorial denotes a public experience of ‘curatorial activism’ for those that engage in person with the meaning-making symbolism of the monument. While ‘curatorial activism’ is a term used to designate the practice of organising counter-hegemonic initiatives (giving voice to those historically silenced and visibility to those omitted from operational constituency), I am developing and advancing the term ‘curatorial dissonance’ in this article to denote the productive possibilities of the conflict that emerges by the simplicity of curation. In the particular research the article draws from, the work produced by the sculptor of the Holocaust Memorial in Athens and its unveiling ceremony in 2010 in the midst of antisemitic attacks and at a site close to the synagogue where Jews of Greece were captured is one of ‘curatorial dissonance’, where conflict meets resistance and inharmonious reception aligns to reflexive-praxis.

6 However, these are conceptualised as opportunities for publics to emerge and not as a substitute for the necessary public awareness and debate that continues to eclipse from the more pervasive ethnonational representations in Greece. This is validated by the recent and important research by

Karasová and Králová (

2022) whose work exploring the political discursive framings of how the Holocaust Museum of Greece (HMG) project based in Thessaloniki has not had any organised meaningful public (or scholarly!) debate. Not surprisingly, this is depicted in the survey responses they received in 2020 where only 5 respondents (out of 76) had just a faint idea of the actual project, which as the researchers suggest exemplifies a symptomatic indication of the limited understanding of the Holocaust in Greece (

Karasová and Králová 2022). Indeed, while the general lack of awareness and vagueness of publicised information yields expectations of an apathetic non-participative public, it is the systematic lack of scholarly efforts to embed educational foundations as to ascertain knowledgeable publics, as such, is what continues to be additionally problematic (

Christou and Michail 2021). In this respect, as advanced previously by

Christou and Michail (

2021), ongoing pedagogical training of scholars, educators and teachers themselves should be seen as a priority area for inclusive pedagogies of equity and justice.

7 Holocaust memory in the contemporary context needs to focus not just on remembering the genocide histories in the past, but also considering how it is relevant to later generations and through which means it can be communicated as to become transformative for their social consciousness and values (

Walden 2015). Indeed, it is promising that within the impacts, disruptions and constraints of the COVID-19 pandemic, Holocaust memorials piloted the potential of social media for Holocaust memory in an experimental context, which in a sense is a validation of the ongoing generational change where social media consumption has been practised for Holocaust commemoration (

Ebbrecht-Hartmann 2021).

Beyond the use of social media, Holocaust education and research involve complex ethical (and moral) dimensions. For scholars who are involved in researching Holocaust education, insights of an incremental fashion to implementing research ethical principles, thus adjusting and reacting to emerging field-specific dilemmas and the fragility of confidentiality of the research process, are a paramount realization (

Knothe 2018). This fragility of confidentiality can also be stretched to the challenging and reconfirmation of friendships and professional relationships when participants are drawn from such pools of contacts with pre-existing long-term rapport. To maximise opportunities to productively deflect any tension into meaningful discussion outside of the research context, one of the parallel self-reflexive actions I incorporated during the period of the research was to join a trauma discussion group within a wider ‘emotional protection team’, along with immersive learning on moral emotions in reconciliation in connection to genocide. These opportunities gave me a greater understanding of my experiences of generational trauma, openness to confront historical and personal instances of dehumanisation, stigma and exclusion while reinforcing my personal toolbox for upstander intervention in everyday life.

Figure 1 includes a selection of vignettes that contextualise the moments of ‘re-membering’ when immersed at the sites during the visits at the Holocaust memorials with participants. While the vignette technique is a method that can elicit perceptions, opinions, beliefs and attitudes from responses or comments to stories depicting scenarios and situations, they can be employed in different ways and for different purposes. These can include being used as a self-contained method or an adjunct tool to other research techniques; how the actual aligning story is presented to participants; and at what stage in the fieldwork they are introduced so as to structure responses in a particular way. They nevertheless offer a situational context and themes to be elucidated especially as regards moral dilemmas and sensitive experiences. In the latter direction, I see the vignettes inserted here as meaning-making discourse to the specific situation of fieldwork immersion and not in isolation as heuristic devices but part of a multi-method approach. It is because of this interrelationship that I draw awareness to the tension that might emerge between belief, perception and meaning-making (

Sampson and Johannessen 2020;

Rizvi 2019;

Kandemir and Budd 2018).

In the next section, I pull together the threads to the affective geographies of Holocaust memorialisation that emerge as timespaces in the feminist mood when analysing the nodes that interconnect in contestations of monuments.

3. Timespaces as Contestations: ‘Re-Membering’ Holocaust Memorialisation and the Feminist Mood

A snapshot of the basic historical facts of Jewish Greeks in the Holocaust, as well as life beforehand and afterward would have to include the key historical studies of core archival and contemporary historiographical interest that capture key themes.

8 One of these being of course the differing origins and trajectories of the Greek-Jewish communities, and the latter concept should not obscure the heterogeneity of the Greek Jews in terms of class for instance, but also, other social categorisations beyond elites and others. There is equally complexity here when it comes to ascertaining meaningful insights of social relations, relations with the state and the heterogenous Greek and Greek-Jewish communities during social interactions. Thus, a social historic view is necessary as well as caution against taking an integrated view in the history of Greek Jews which would inherently undermine the nuances involved in understanding their profiles, portrayals and trajectories. First-hand accounts of survivors

9 are particularly illuminating in this regard.

Greek-Jewish historiography shares a number of elements of Greek historiography, be that in its thematic and methodological ethnocentrism that yields homogenisation and a top-down approach with an absence of an intersectional social history (

Avdela 2014). This would be an attempt to dismantle the rigid boundaries of a community and to accept that it is a fiction to believe that Greek Jews were and are one unified entity without layering of ethnic, gender, regional and class identities, at the very least, with crossing and interactions amongst generations and other groups.

Touted as the ‘Jerusalem of the Balkans’, the Mediterranean port city of Salonica (Thessaloniki) was once home to the largest Sephardic Jewish community in the world, and thus the historical context of the Jewish communities of Thessaloniki is inextricably linked with the memory of the Greek Shoah. As mentioned earlier, it is only since the 1990s that organised efforts have been put into the publication and dissemination of histories of violence, genocide and systematic extermination by the Nazis of this long-standing Jewish community during the German occupation of Greece. There is a realisation that the silence of these histories came along with censorship of the descendants of the 1492 expulsion of Jews from Spain. Subsequently, migrant waves from the Iberian Peninsula, the integration of Thessaloniki to the Greek state in 1912 and a decade later after the 1922 Asia Minor Catastrophe the influx of Greek refugees from Anatolia made a dominating presence of Greeks more pronounced within the long-standing establishment of urban Jews with a prominent socio-economic and politico-cultural presence (

Dermentzopoulos et al. 2023). Demographically speaking, while in 1940 the Jews were about 20% of the total population, less than 5% survived the Nazi extermination already happening in 1942, aided by antisemitic collaborators who also benefited economically with whatever they could get their hands on following the Nazi looting that ended in 1944, amalgamating even through legal means the ownership of businesses and residences (

Benveniste 2019;

Fleming 2008;

Mazower 2005;

Saltiel 2020). Almost 95% of the city’s 50,000 Jews did not survive the war, most of them deported and exterminated in Poland. This major Jewish community were mostly Eastern Sephardim (

Saltiel 2020;

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum n.d.). Nowadays, approximately 5000 Jews live in Greece. The current centres of Greek Jewry are Athens (3000) and Thessaloniki (1000) and a handful of smaller towns, amongst them Ioannina.

10Recent conceptualisations of ‘dark tourism’ experiences through visits to sites that are associated with war, genocide and violence has suggested through new research that explorations of the darkest chapters in human history (such as the Holocaust) might become inspirational for people to act on social change and promote human rights (

Soulard et al. 2022;

Bareither 2021). At the same time, this kind of exploitation of human trauma and tragedy triggers multiple moral conflicts. These spaces are liminal and invite transgressive behaviours by individuals for mechanisms of moral engagement to emerge when individuals take ownership of their actions (

Sharma 2020). Moreover, such visits can be theorised as affective socio-spatial encounters and such geographies of affect are imbued with experiences of political and ethical charge (

Martini and Buda 2020).

The Holocaust as a ‘trauma drama’ through ‘the social benefits of pity’ has contributed to a moral remaking of the postmodern (Western) world with a moral ambition and ethical message of a path to a more just and peaceful life (

Bauman 1989;

Nussbaum 1992;

Alexander 2002). These kinds of visual narrations can be seen in the representational design of contemporary Holocaust memorialisation. Some of the generative principles that characterise contemporary Holocaust memorials as a ‘new genre’ of commemorative art distinct from older forms include the objective of addressing transnational audiences; reflecting in their design representations of multiple meanings; and their utility as new repertoires of symbols, forms and materials to represent those meanings (

Marcuse 2010). These memorials and monuments as tangible manifestations of collective cultural and social memory can also be seen through the lens of the ‘Europeanisation of Holocaust memory’ that extends to transnational remembrance education (

Kucia 2016a,

2016b;

van der Poel 2019). Holocaust memorialisation can be performative in terms of individual memorial actions and the impact and transformative potential of such practices. What is more vivid in impact is the potential for embodied, emotional connections and sense of immediacy/urgency between the past and present. However, the ‘lack of understanding concerning how visitors rationalize feelings and endow them with meaning … not yet known how difficult emotions, such as anger, disbelief, distress or outrage shape visitors’ attitudes to learning and commemoration’ is an area where more research is pertinent (

Popescu and Schult 2020).

Microhistorical approaches to researching the Holocaust in Greece and Jewish life during the Axis-occupied period of Greek history provide a very important window into everyday life and expose the vulnerabilities and experiences of Jews as citizens (

Saltiel 2017,

2019). These kinds of studies have also been noteworthy in highlighting the once striking status of Thessaloniki as ‘the Jerusalem of the Balkans’ (

Molho 2015). Yet, the Holocaust still has not been fully incorporated into the Greek collective national consciousness of historicity and temporality for more than sixty years, leading to laws and commemorations and a sprinkling of educational activities only happening in 2004–5, coinciding with Greece’s membership of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance.

These timespaces as contestations in Holocaust memorialisation need to be seen as part of the historical geographies that I seek to situate here through a feminist lens. This is a pivotal point in underscoring the urgency for every history of the Holocaust to employ gender as a conceptual tool of analysis, understanding a gendered sense of self and victimhood (

Waxman 2017). Feminist ethnographers engaging in research on gender and Holocaust memory frequently encounter methodological tensions during the research process. In the field of feminist Holocaust studies, a number of ‘departures’ and debates about representation exist, especially with the repetition, circulation and discussion of memorialisation encounters in setting the context of how the Holocaust is conceptualised in relation to the experience of visitors. Among academics, a paradigmatic shift to Holocaust as a ‘crisis of representation’ in contemporary social, political, aesthetic and ethical knowing can become a pathway to understanding what can then be the response to this crisis. An indicative part of that crisis as this article contends is the lack of feminist scholarship on any topics in relation to Jews in Greece, the Holocaust in Greece, Jewish life in Greece, memory and Jews in Greece, etc.

11 When problematising our ethos to understand lives and identities emerging out of histories of violence, fragility and vulnerability, histories of the Holocaust as discomforting stories of survival should engage the prism of a feminist lens and experiences of women. These connections are important for more community-engaged research and the representation of women as actors and agents in the stories we collect and tell (

Jacobs 2004;

Disch and Morris 2003;

Ubertowska 2013;

Sheftel and Zembrzycki 2010).

The vignette extracts from participants all engage with the themes articulated throughout the article. They are illuminating of a range of affective reactions to the dissonance, conflict and memories created, as they experience the visit in an immersive context entering the monument site. The dissonance appears first-hand when the aesthetic beauty of the piece is juxtaposed with its representational history (‘I am sad knowing that this beautiful piece of art represents millions of people annihilated’; ‘It has been emotionally and physically exhausting to bring myself to complete this visit’; ‘I have been feeling the tension rise as we approached the memorial’; ‘I was very sceptical if I could manage to get through the experience’; ‘My heart has filled with so many different emotions’; ‘Being overwhelmed by such powerful emotions’).

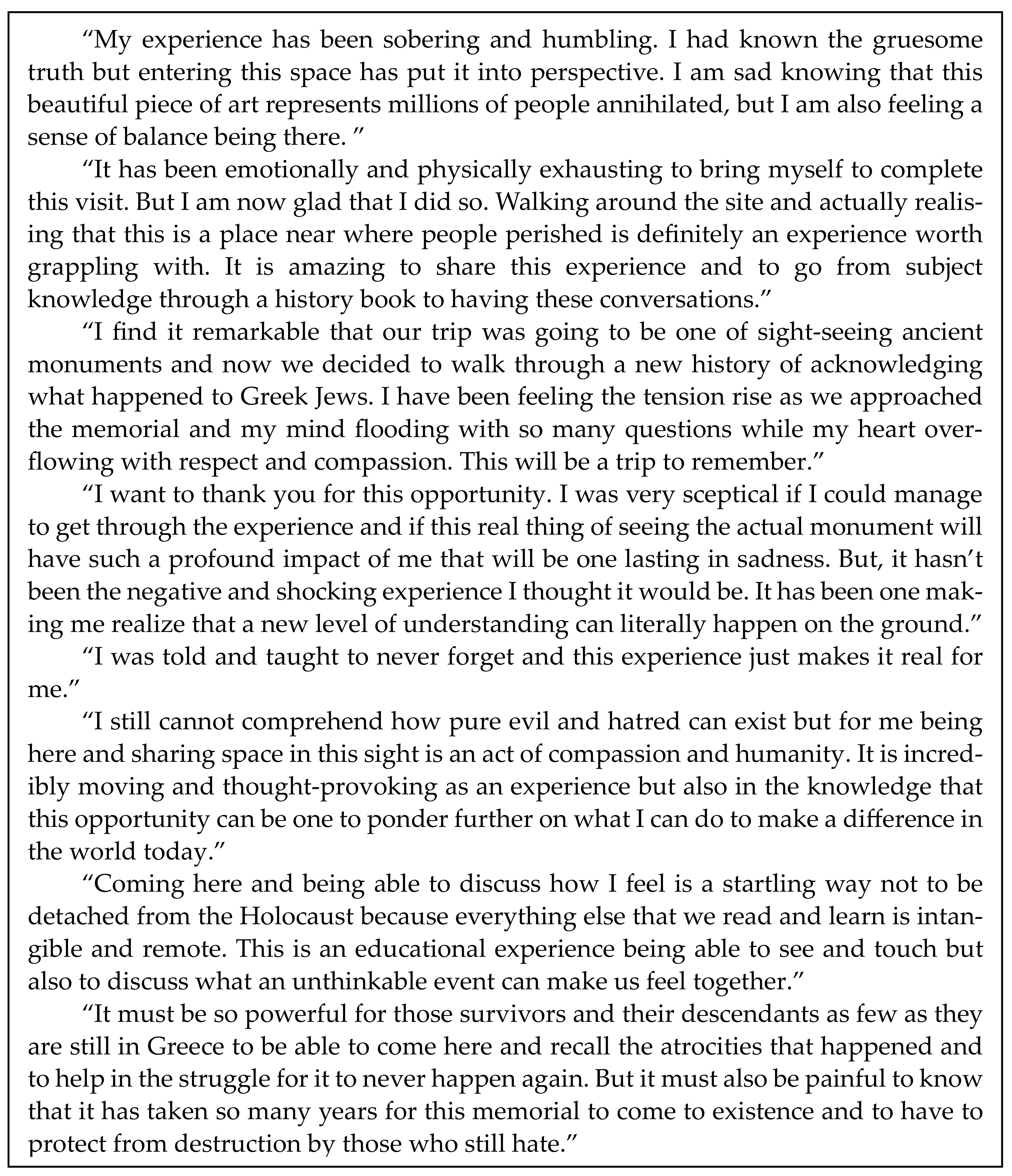

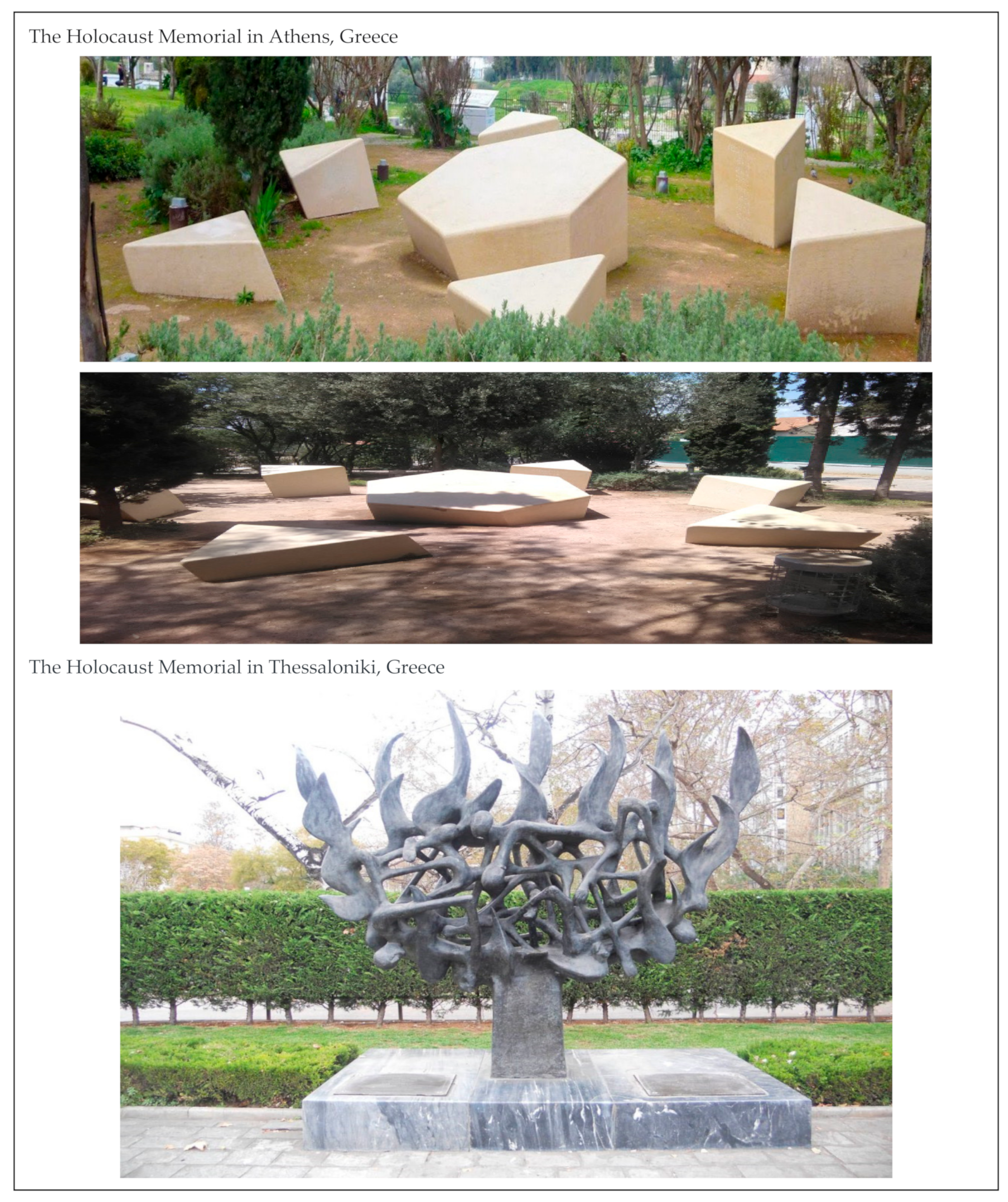

There is a filtering of emotions that happens through the curatorial experience of the monuments in their simplicity, but also the poignancy of their shapes triggering connectivity (Star of David/Athens Holocaust Memorial; Menorah in flames/Thessaloniki Holocaust Memorial) to the historical legacy of Greek Jewry, but also its emplacement in the urban landscape.

The Athenian memorial is carved in the shape of a broken Star of David, the ancient symbol of Judaism acting like a compass so the sculpture points to the cities and villages across Greece from where tens of thousands of Jews were gathered and deported. In the Jewish tradition, it symbolises memory and death but with the stillness, quiet calmness emanating through the herb garden it is reminiscent of healing, revitalisation and ultimately survival following struggle. As a catalyst for hope and renewal, but with the reverence of never forgetting its locational grounding, the memorial is symbolically and aesthetically infused with landscape herbal aromas and the fleeting light shimmering through the tree branches.

The Salonican sculptural monument is also set on a marble base but from a distance appears abstract while close inspection reveals the form of a menorah, a sacred candelabrum with seven branches used in the ancient temple in Jerusalem and in Jewish worship. But, the menorah is built of human bodies engulfed in flames, wavering and pointed, reaching to the sky and depicting the forms of six human figures with distorted stretched bodies, skeleton limbs entangled and immersed in fire. The symbolism is powerful and so are the emotions (‘I still cannot comprehend how pure evil and hatred can exist but for me being here and sharing space in this sight is an act of compassion and humanity’; ‘Coming here and being able to discuss how I feel is a startling way not to be detached from the Holocaust’; …‘painful to know that it has taken so many years for this memorial to come to existence and to have to protect from destruction by those who still hate’; …‘the horrors of what people experienced in the atrocities that happened makes it humbling to be here’).

As the vessels of memory, monuments mediating cultural narratives of the Holocaust through experiential visits to memorialisation places is a unique opportunity to share empathy and humanity. Societies need to remember and to come to terms with their pasts. They need to move from obscure objects to illuminating historical realities as a pathway to constructing public memory which will reckon publicly with violent and repressive histories (see

Figure 2).

4. Concluding Reflections: Heritage Healing as Justice Eduscapes

Finalising the writing of this article and engaging with subsequent revisions occurred during two different visits to Israel (February/March 2023) and Palestine (September/October 2023) in a context of immersive storytelling when revisiting field notes and data while engaging with the cultural translations of meaning-making with that data. The data sources along with auto-ethnographic material were re-created and interpreted by the researcher within the un/making of histories and power. All this messiness involves emotions, speculations, subjectivities, ambiguity and instability, all inherent with thinking and writing Holocaust memory and memorialisation. There is no automatic authority or anchoring of such historicities within a stable paradigm, but rather this enmeshing of practices translates social processes in interaction with participants and their materials, then interwoven into the article. This is an article that encounters risk, as a methodological means of sense-making, but also as an outcome of the actual output in challenging and even contesting standard approaches to writing up research, being at the margins and cross-roads of disciplines, methods and theories. In this direction, it aims to embrace ‘histories’ as vehicles to challenging public humanities as a space of historiography to enable discussions on the conflictual aesthetics of memorialisation with what I describe as curatorial dissonance.

The experiential visits demonstrated that the monuments have a highly politicised and contested heritage, but also an educational value that the representation of a community brings when its truths are displayed as public space interventions. These kinds of monuments can become experiential depictions of public history and have the power to unveil hidden histories and by extension to destabilise what is conflated as otherwise endorsing societal silences, case in point, Greek Jewry as a

de facto component of Greek history. While the public display of fragments of historical amnesia can also become a central trigger for controversy, it is precisely this role of public history constructed through display in public spaces that offers pluralistic understandings of identity and revisionist historicity/historiography to be appreciated by the general public. There are issues at stake here when national histories are only portrayed in a positive light and there are no opportunities for public debate, dialogue and civic lessons in the streets and the classroom. These can become what I term important ‘curatorial accountability nudges’ that can be utilised as options to ethical reflexivity for the public in incentivising people to take the personal agency and freedom of choice to engage with human dignity through visual guidance first and then educational ethics of learning history holistically, above and beyond the ethnonational optic. These are instances of ethical nudges that are important for social and community cohesion (

Schmidt and Engelen 2020).

Of course, there is no doubt that curatorial accountability nudges are at the crossroads of dissonance and discomfort when they come with sufficient alertness to the wider political context and conscious measures to display publicly works that frame opportunities for dialogic spaces. At the same time, it is very critical that due consideration is given to the ways in which any potentially controversial work exhibited and curated does not include removing it from public sight. I would argue that indeed it is equally beneficial for public history that discursive public spaces for dissonance are created and enabled, not contained or concealed. Rather, the onus is on a holistic collaboration between heritage professionals, academics, the state and local communities, so single national narratives are also destabilised and become more pluralistically inclusive. For example, ‘relational antagonism’ is an important concept for democratic societies where relations of conflict are not simply erased but sustained so as to avoid an imposed authoritarian consensus where a total suppression of debate occurs and it ceases to exist. Thus, framing the public space through relational aesthetics as the aesthetic equivalent of a dialogic dissent that might involve instances of friction, the discomfort of unease, the instability of confrontation and the like, are opportunities for a society to challenge its own contradictions (

Bishop 2012). Through such challenges, there can be opportunities for reconciliation and healing with the past, as a step to remembrance of the past into the future, as an exposition against the counter-productive end of history theses and all the other endisms of our era.

Building communities of care and caring through heritage healing can create a new type of educational landscape that shifts the trauma of oppression, eliminates marginalisation and supports futures that are free from racisms, antisemitism and structural violence. Holocaust heritage can develop justice eduscapes and should become an objective for the Greek state and its educational provision. It is important that opportunities in Greece are developed for community development that will perform transformative work that disrupts systems of oppression and will build bridges for healing. Such healing also emerges through knowing and accepting the diversity of histories in Greece, and that of the Jews of Greece is one component that still remains largely absent from the national narrative.

There are key reasons to advocate for the embedding of Greek-Jewish histories and the Greek-Jewish Holocaust, as well as the memorialisation of those histories in how students in Greek higher education confront considerations of moral implications for their lives in exploring these events. Above all, such eduscapes will offer opportunities for dialogue with students on what moral implications and moral insights can be drawn by examining the experiences of Greek Jews and parameters of the Greek-Jewish Holocaust. Students can grapple with the meanings of humanity, the essence of what it is to be ‘humane’ and how genocide as a human behaviour is an act of ultimate evil that requires constant consideration by replicating acts of ultimate good and humanity.

In addition to the moral imperative, the importance of embedding these diverse histories in the curricula of state education in Greece is highlighted by the contemporary need to advance public histories, and proposing such eduscapes is a core component to such an objective. In recalling atrocity for the next generations, we make a direct intervention in educating them toward humanitarianism and acknowledgement, so history shapes the contemporaneous fragility of our times, not through denial and demise but in the politics of peace. As researchers, educators and storytellers, we have moral responsibilities in the development of a human rights genre that is an activist movement, not a fictive ideal. This work starts in the classroom.