Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Flails in Antiquity

3. Cultural and Literary Context of Flails in the Medieval Era

In this context, the flail of God Attila refers himself as being can be misconstrued due to a tendency of the meaning between flail and scourge to merge, though the reference to threshing means this requires somewhat deeper analysis. This merged meaning of flail and scourge arises from the Latin term Flagella, meaning flail (several types), and also scourge (the whip-type devices) to refer to (Nicolotti 2017), in the latter case, a scourge in its alternate definition as a source of great suffering or trouble. Similar observations are seen in French with the term fléau, where alone, this word refers to scourge, but with the suffix d’armes, refers to the weapons described here (Havard 1876). The evolution of language incorporated the further meanings of the word flail, at least in English, from just the farming tool to the associated military definition primarily discussed here (Izdebska 2016); the chaotic flailing of threshing flails is indeed the origin of the modern adjective to describe wild circular motions (such as of the arms), representing a further branching of the semantics of the word (Hill 1998).“Then Troyes: Bishop Lupus asks Atilla (Attila), “why do you destroy the whole land?”Atilla (Attila) says, “I am God’s flail; open the gates, and I will thresh both woman and man!”

4. Depictions and Descriptions of Threshing Flails as Improvised Weapons in Western, Central, and Southern Europe in the Early and High Medieval Eras

During the Anarchy (1138–1153), the English war of succession that followed the death of Henry I (d. 1135), a power struggle between two rival strands of the royal family resulted in numerous campaigns across England and modern-day France. One secondary source attests to, as with the later description of Jordan Fantosme (see below), the “peasants and churls turning out and driving the hated Guirribecs back over the border with fork and flail” (Green 1888), though no original period reference is provided to corroborate this. In this context, “Guirribec” was used a derogatory term for the Angevins, who were likely suffering from dysentery (Bradbury 1990).“Li vilains des viles aplouentTels armes portent com ils trouvcnt;Machus portent e grans pelsForches ferrdes e tinels.”“The villeins of the towns applaud (gather?)The arms bear where they findMarch forth…?Forks of iron and [heavy wooden implements].”

One of the earliest primary references I am aware of where threshing flails are used as improvised weapons outside of a fictional setting comes from The Chronicle of the War between the English and the Scots in 1173 and 1174 by Jordan Fantosme (Hosler 2017; Day 2010; Short 2022). He describes their use against Flemish mercenaries alongside (pitch)forks (the extended modern translation is provided for context):“Sulc was die eenen bessem brochte,sulc eenen vleghel, sulc een rake,sulc quam gheloepen met eenen stake.”

In this context, given the specific reference to the villains and the known symbology of “fork and flail” as those of servitude and the lower classes, he must be referring to threshing flails as tools of the peasantry. Matthew Paris repeats this tale in his Historia Anglorum (c. 1250–1259) (Oman 1898).“N’i aveit el païs ne villain ne corbel/N’alast Flamens destruire a furke e a fleel”“In all the countryside there as neither villein nor peasant who did not go after the Flemings with fork and flail to destroy them… …by fifteen, by forties, by hundreds and by thousands/by main force they make them tumble into the ditches … Upon their bodies descend crows and buzzards/who carry away the souls to the fire which ever burns’”

5. The Weaponisation of Threshing Flails in the Later Medieval Period

Górski and Wilczyńska similarly describe a Moravian noble’s fear in his words of warning to the King (Holy Roman Emperor), “I am very afraid of peasant’s flails” (Górski and Wilczyńska 2012). There are several contemporary and later manuscripts which depict the Hussites with their weaponised threshing flails, notably the Jena Codex (c. late 15th—early 16th century, currently held in the Library of the National Museum of the Czech Republic; see fol. 76r).“A flail such as this in the hands of country peasants, who were accustomed to using it, must have been a terrifying weapon which could bash the finest helmets of the Crusaders (against the Hussites) to smithereens).

6. A Few Comments on Scourges

7. Development and Use of War Flails Outside of Western, Central, and Southern Europe up to the Early and High Medieval Eras

8. Depictions, Descriptions, and Archaeological Finds of War Flails in Western, Central, and Southern Europe in the Early and High Medieval Eras

I will highlight references to flails where present within the various chansons, poems, and other works of folklore, but please note that this is not an exhaustive list but based more upon the abundant secondary sources which cite and mention these; translations are approximate based upon the availability of original texts, translated versions, and dictionaries, where these are available. Furthermore, some of the poetic or textual references may predate their first recorded written examples by a significant amount of time (decades or even centuries) when drawn from oral histories of their parent peoples, as these were commonly adapted and changed over time. Where possible, a commentary of the apparent construction of the weapons depicted and on the reliability of the source(s) is provided. The sources are presented in approximate chronological order. In some cases, the original texts are not available, where I would refer readers to the cited secondary sources for guidance. Several questioned depictions are also highlighted, and where these have been suspected over the years, this is discussed along with previous assessments as to their authenticity.“Ne sont que III matieres a nul home antandant: De France et de Bretaigne et de Rome la grant.”“There are only three subjects matters for any discerning man: That of France, that of Britain and that of great Rome.”

Flails (reported as schlachtgeissel—lit: “battle whip”) are attested as being used in 10th century Germany during the second Battle of Lechfeld (955) in which the Kingdoms of Germany and Hungary clashed; these are described as consisting of a short wooden handle with three or four chains, at the end of which an iron ball studded or filled with lead was attached (Köstler 1883; Bánlaky 1928). This account may arise from the Annales Altahenses or similar period document (Pohl 2004; Négyesi 2003). Bánlaky suspected that the Schlachtgeissel originated from the Frankish Empire, and its use was passed onto the Carolingian successor states, used as a secondary or tertiary weapon by the German cavalry (Bánlaky 1928; Jócsik 2022), as was also likely the case for the steppe peoples who first introduced such weapons (kistens) to parts of Central Europe (Zhirohov and Nicolle 2019). The flail may have been introduced to the Carolingians by the Huns (Gotzinger 1885; Jähns 1880). If this is the case, a likely explanation is provided for the significant prevalence of flails in the many tales of the Matter of France, England, and further afield. A plethora of 10th and 11th century grave finds from present-day Central and Eastern Hungary would support the notion that flails were also used by the Magyars (fighting for or with the Hungarians) during this time period (Jócsik 2022).“Ar Vretoned a weliz o vac’h el leur e louc’hKen a lame pellenou demeuz ar pennou blouc’hHa ne ket gant fustlou prenn a vac’h ar VretonedNemet gand sparrou houarned ha gand tried ar virc’hed.”“J’ai vu les Breston batter le blé dans l’aire fouléeJ’ai vu voler la balle arrachée aux épis sans barbe.Et ce n’est point avec des fléaux de bois que batten les BretonsMais avec des é[ieux ferres et avex les pieds des chevaux.“I saw the Breton batter the wheat in the stomped areaI saw the chaff fly off the beardless earsAnd it’s not with wooden flails that the Bretons strikeBut with iron spikes and horses’ feet.”

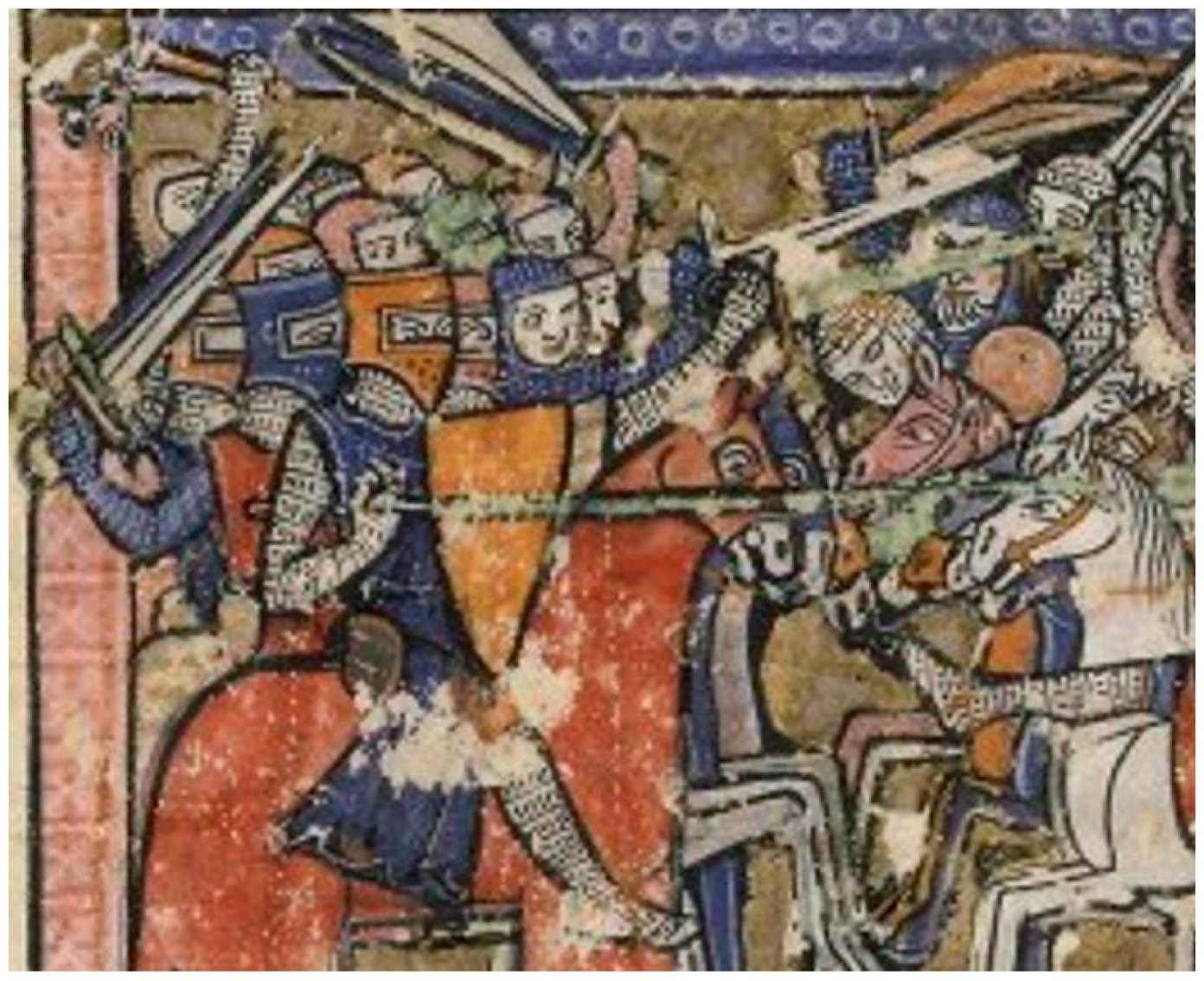

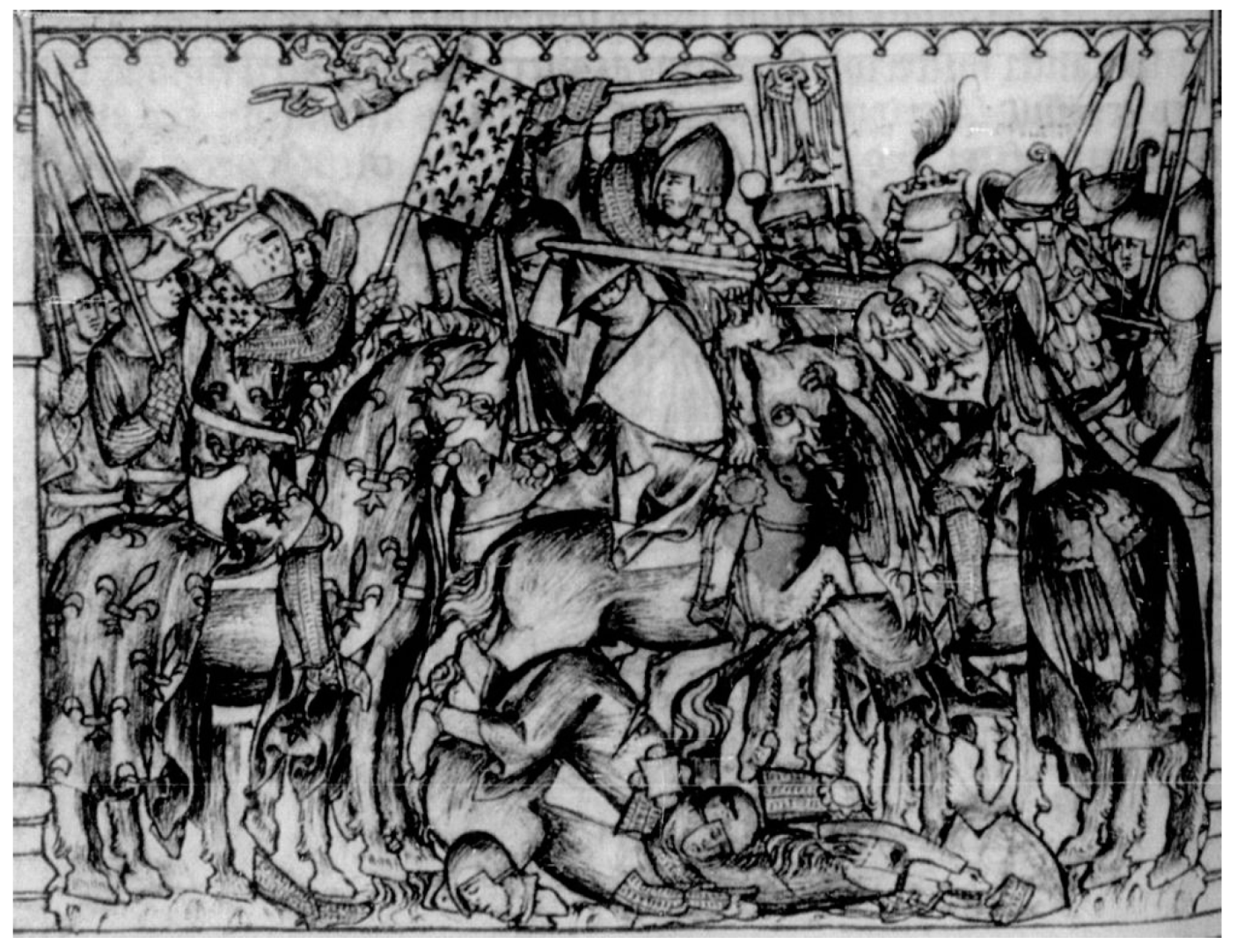

The 12th century manuscript La Chanson de Jerusalem describes flails (possibly threshing flails (plomées), though these are also described as “large clubs with dangling chain”) being wielded by the Tafurs (Frankish Catholic zealots who adopted a vow of extreme poverty) during the 1099 Siege of Jerusalem. The Saracens are described as being similarly armed (perhaps with ball-and-chain flails), one of whom “smashed a flail down on the King of the Tafurs… (leaving him) dripping with blood, the blow from the flail having smashed his nose and badly damaged his head and brains”. Two Christian knights (Eurvin of Creel and Wicher the German) are noted as being similarly set upon by “infidel pagans… wielding large thick maces and hinged flails, big lead clubs…” This piece clearly describes flails of various types being used by both sides during the First Crusade (1096–1099) (Sweetenham 2016; Esposito 2018). The following excerpts are drawn from the presentation of Esposito (Esposito 2018).“Li Romain as murs les atendentQui à mervelle se desfendent… (3090)…Lancent dars et plomées ruentMaint en abatent et maint tuent”“Romain had walls waiting for themWhich were wonderfully defensible……Arrows flew and [lead (ed projectiles)] were thrownMany were cut down and killed…”

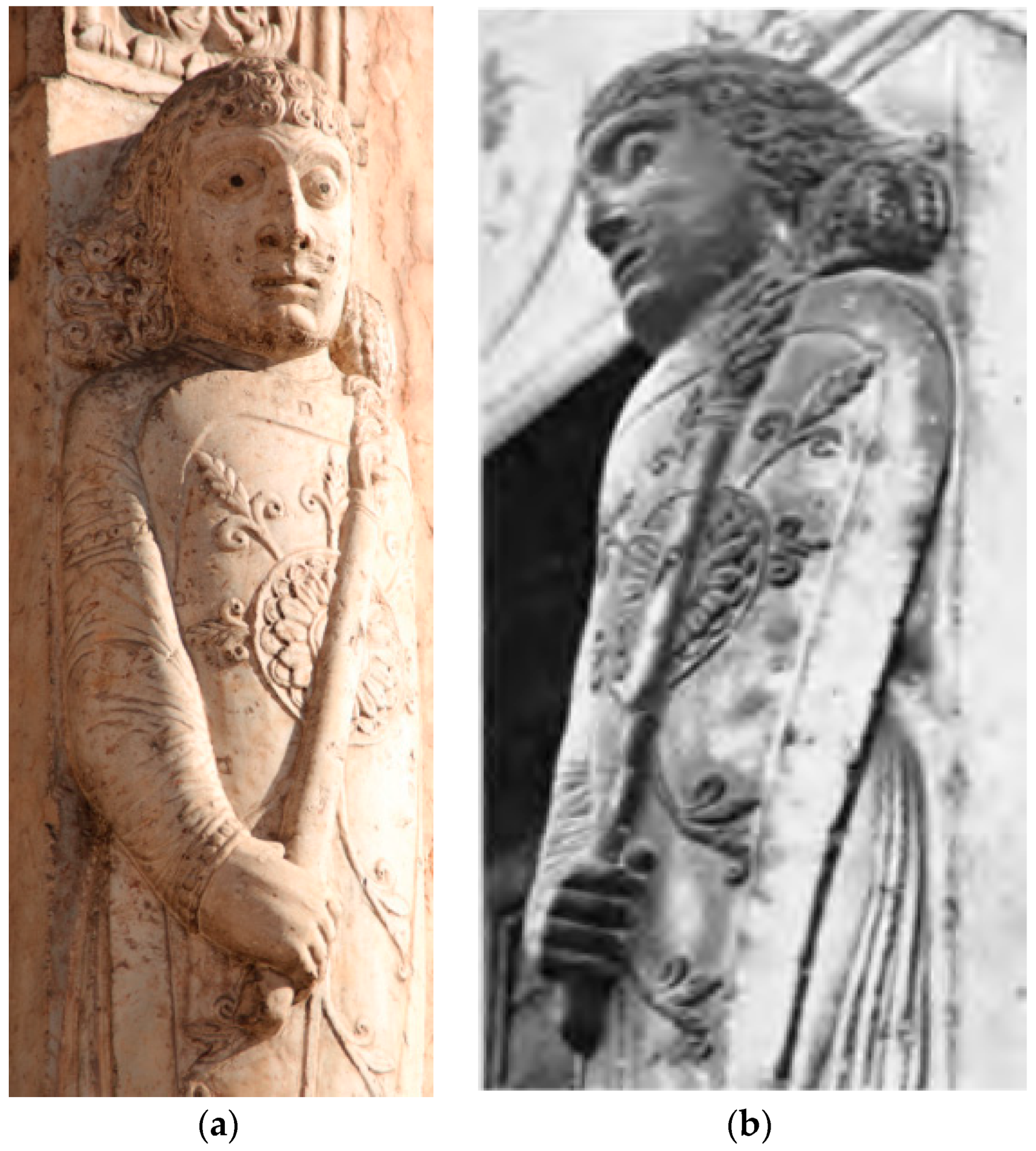

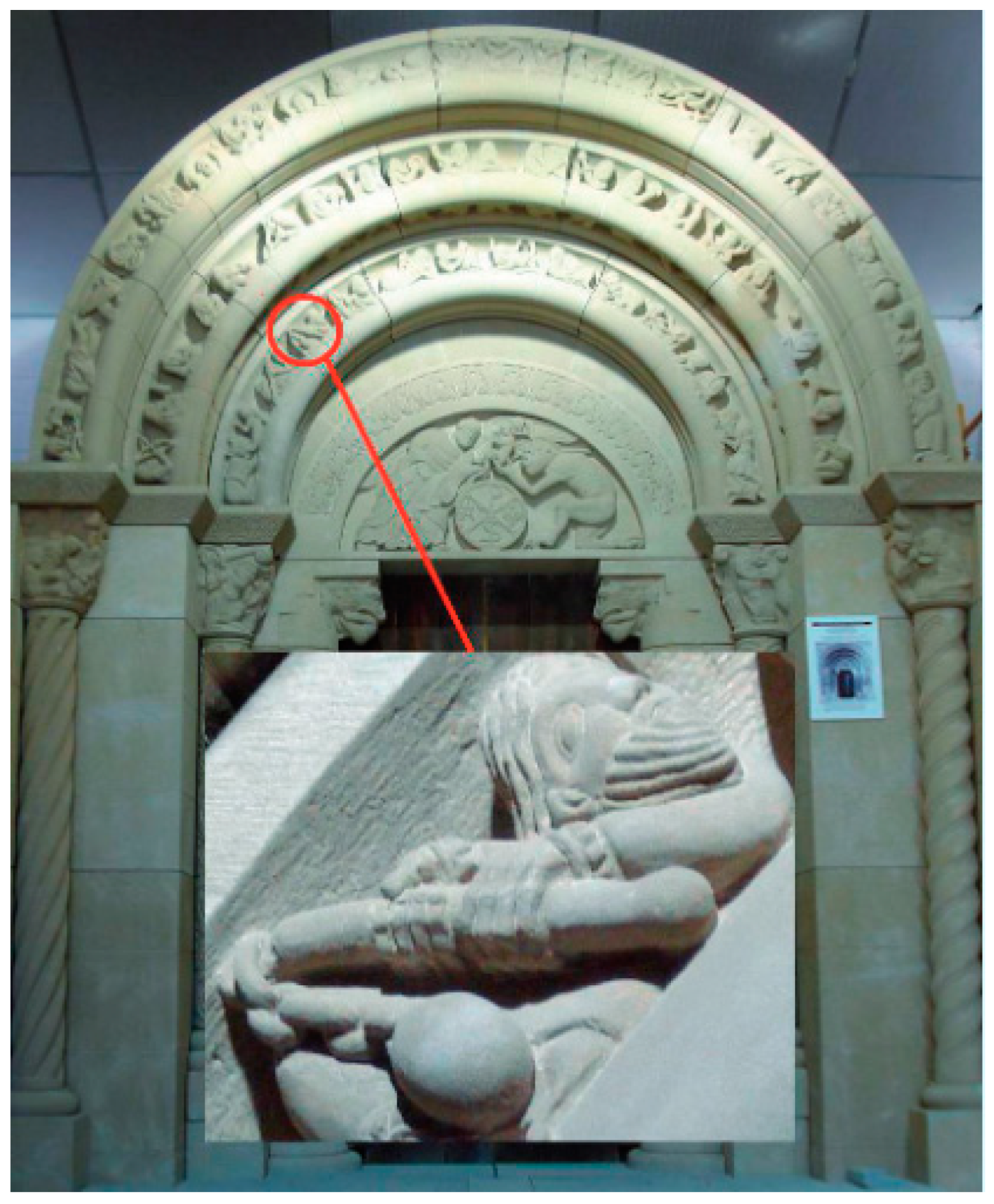

The Song of Roland (Chanson de Roland), is a French epic poem, possibly written by the poet Turold (Turoldus in the manuscripts themselves) around the turn of the 11th century (est. 1040–1115), which describes the battle of Roncevaux (778) from the time of Charlemgane (Thibout 1966). One of the characters in the poem, Olivier (Oliver), is described as using a ball-and-chain flail, with depictions of this character in various medieval locations including as a gate guardian at the Cathedral of Verona, Italy (c. 1139, Figure 19) (Monfrin 1965; Thibout 1966; Beaud 2017; Spiro 2014; Moreno 2015; Agrigoroaei 2018), depicted opposite Roland, who is more conventionally armed (with sword and shield) and armoured in maille.“Ha! Dex! La n’ot mestier gius ne gabbi ne ris.Bauduïns de Belvais fu navrés ens el pisEt Harpins de Boorges devant en mi le visEt Ricars de Calmont estoit el cief malmisEt d’une grant plomee ferus Jehans d’AlisSi que li ber en ert encor tos estordis. (vv. 2374–2379).”“Anuit m’est avenus uns damages mortals,Al besoing m’ont fali nostre malvais deu fals.Mais tant les ferai batre de fus et de tinalsEt de maces plomees, de bastons et de pausQue ja mais n’aront cure de tresces ne de bals! (vv. 1762–1766)”“Cascuns porte en se main u maçue u baston,Plomee u materas et piçois u bordonU gisarme aceree u grant hace u piçon. (vv. 1823–1825)”“Es vos le roi tafur par mi .I. sablonalA .X.M. ribaus: cascuns tient hoe u palU gissarme u picçois d’acier poitevinal.Portent mals et flaiaus, fondefles et mangal. (vv. 1982–1985)”“Portent haues et peles et grans fausars et pis,Gisarmes et maçües et mals de fer traitis,Trençans misericordes et cotels couleïsEt plomees de coivre a caaines assis.Li auquant portent fondes, molto nt caillos coillis (vv. 3012–3016)”“Es vos le roi tafur et dant Pieron corantEt Tafurs et Ribals qui molt vienent huant:N’i a cel ne port hace u macüe pesant,Coutel u grant plomee a caaine pendant,U pouçon u piçois u alesne poignant.Li rois tafurs tenoit une grant fauc trençant,Entre paiens e mist, tant en vait craventantQue par mi les ocis ne pot aler avant. (vv. 5912–5919)”“Des mors et des navrés vont la terre covrant,Fors de Jerusalem les mainent reculant.Tos tant fierent sor els a tas demaintenant,As grans maces de fer les vont jus craventantEt as grandes plomees contre terre tuant.Del sanc as Sarrasins i ot plenté si grantContreval le fossé en vont li riu corant. (vv. 7546–7557)”

Some degree of confusion arising from the multiple meanings derived from certain words can be evidenced by references to the plomée in the Roman de Thebes (Romance of Thebes), a mid-12th century (c. 1150–1155) French epic poem believed to be an abbreviated and adapted version of the classical Thebiad. The story is fitted to 12th century French methods of warfare and chivalric code, and includes several references to the use of a plomée (Constans 1890; de Lage 1966), at least one of which refers to something akin to a discus (v. 230–234 presented below) (Mosca 2020; Ferlampin-Acher 2007), while others are clearly in reference to the “leaded mace” or flail (v. 33–37 and 4175) (Mora-Lebrun 1995). This story was also likely adapted into the late 12th century Anglo-Norman romans d’aventures entitled the Ipomedon and the sequel Protheselaus. These excerpts are taken from the full-text provided by de Lage (de Lage 1966).“S’o ot plomées et maint fanssart pesantEt maintes maces et espées tranchanz”

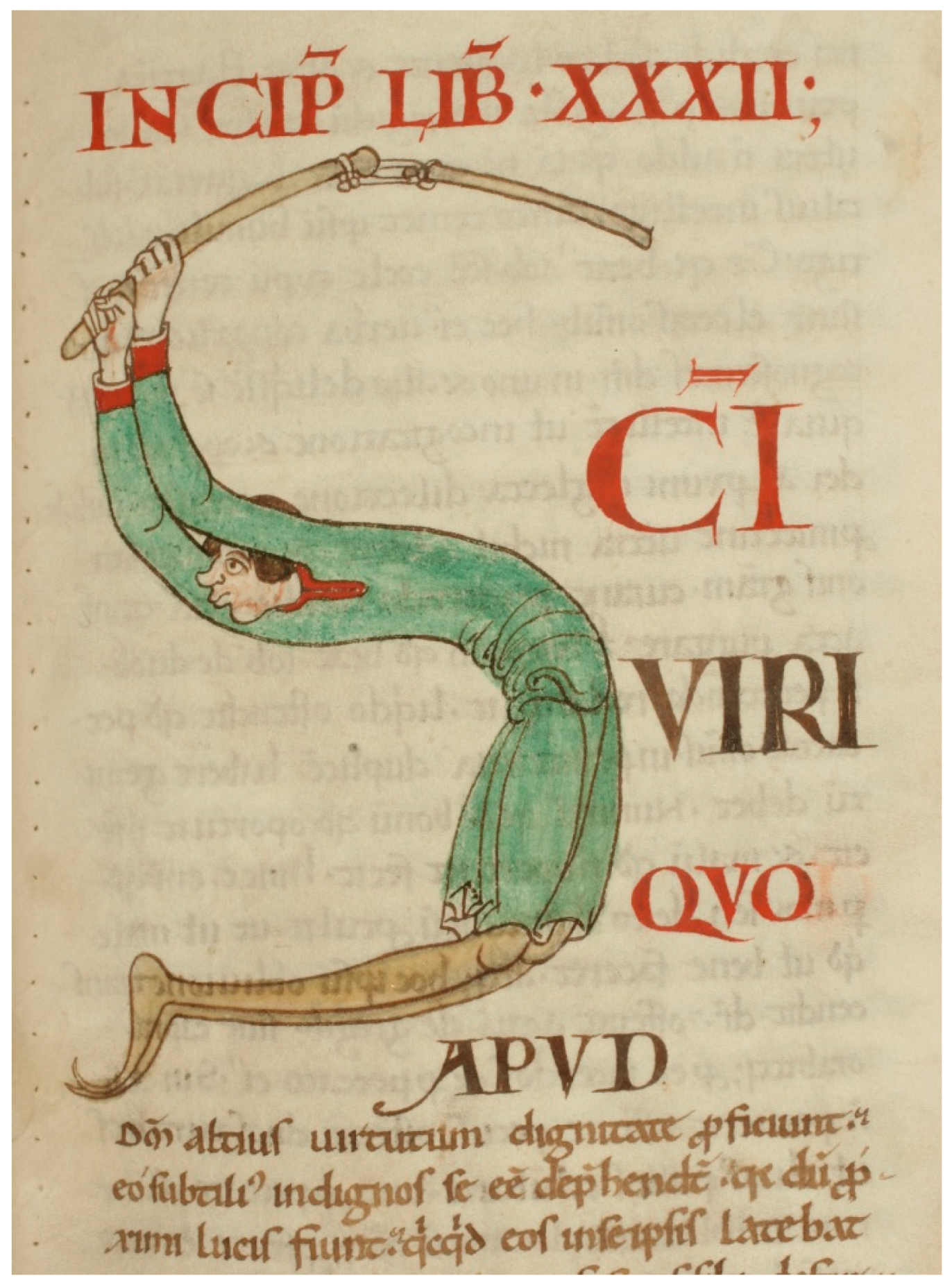

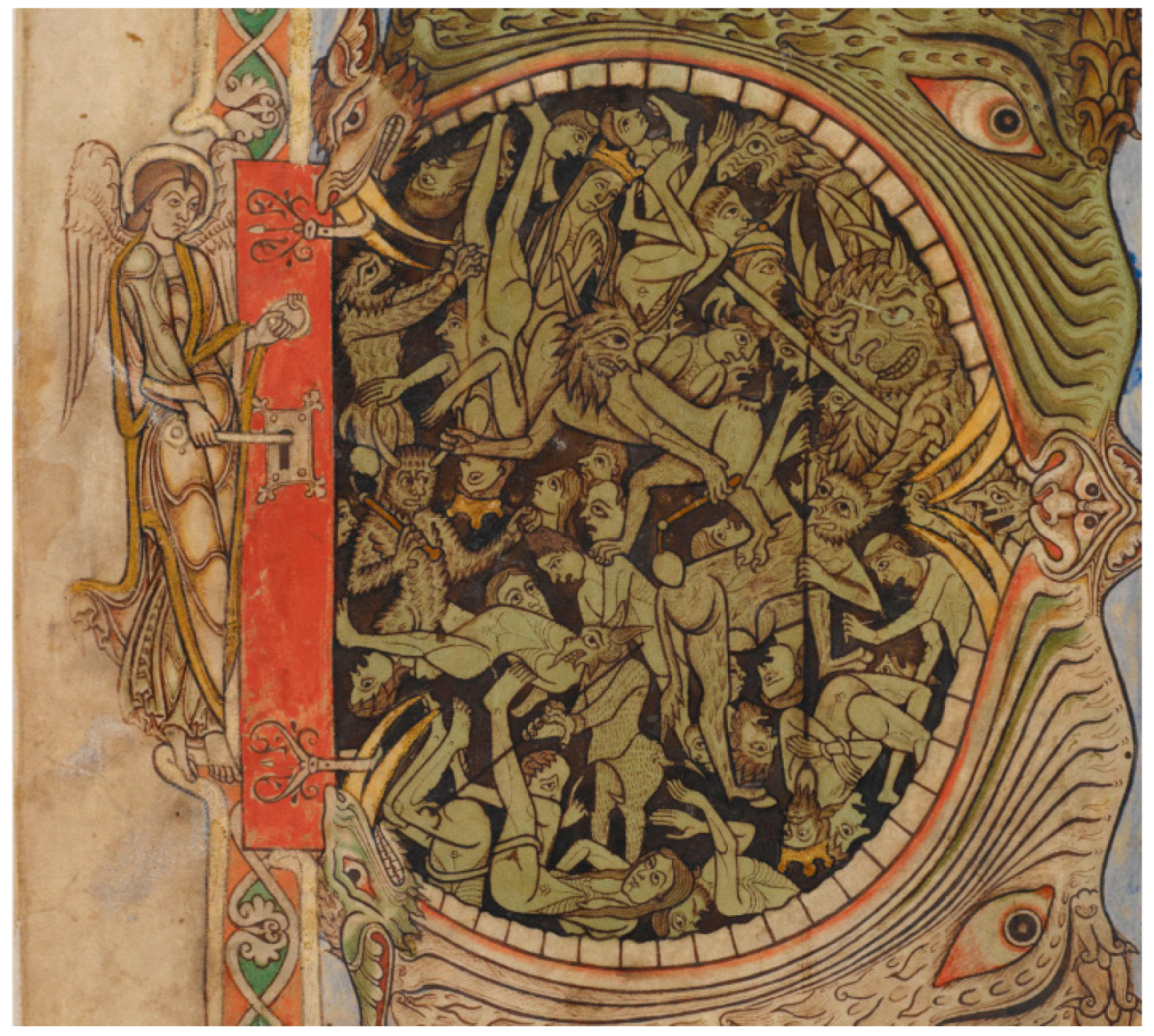

One of the earliest examples of a multi-headed flail is presented in a folio (97v) from the German manuscript Stuttgarter Passionale—Par Hiemalis (cid.bibl.fol.57, Figure 20), dated variously between 1130 and 1175. This folio depicts an unarmoured man wielding a three-headed ball-and-chain flail in one hand. The illustration is lacking the colour of some other depictions, but we can infer from the black hue of the balls and chains that this was intended to represent construction of iron. The balls of the flail present are round in nature, rather than spiked as in some contemporary depictions. The digitised images cut off two of the balls of the flail, but these are clearly visible on the opposite page, as pictured. As with one of the threshing flail depictions presented above, this image is worked into a highly stylised letter.“N’i avoit pas esté grant pose (230)que es geuz sort une melleepar la raison d’une plomee (discus)que li danzel iluec gitoient,qui de giter mout se prisoient”“Car il n’ont pas escus de chesne,Espiés de fer, hanstes [de] fresne,Elaives ne lances ne espees, (2720)Maces de fer ne granz plomees (flail)For solement danz Jupiter,Qui tint un dart agu de fer.”

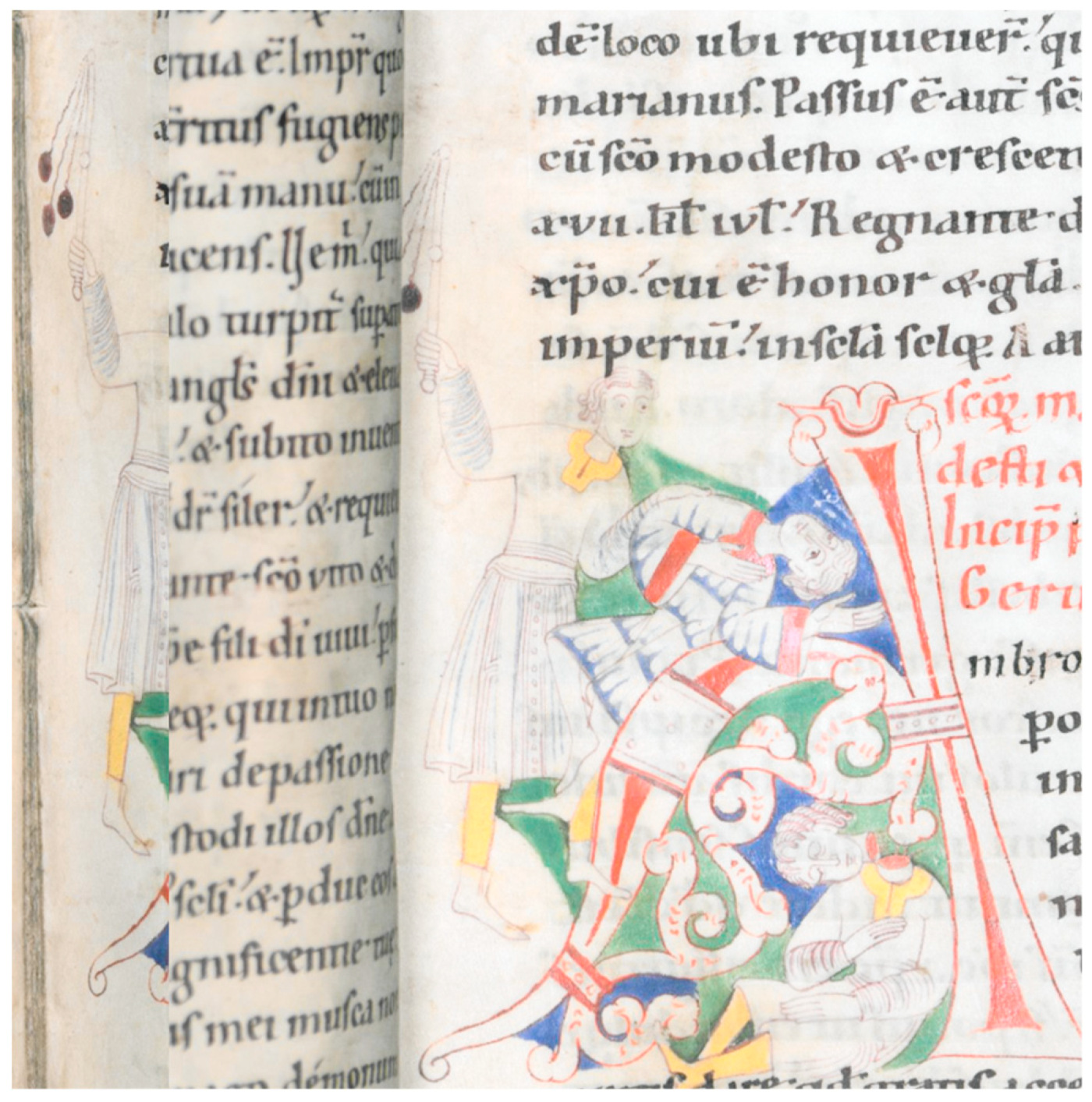

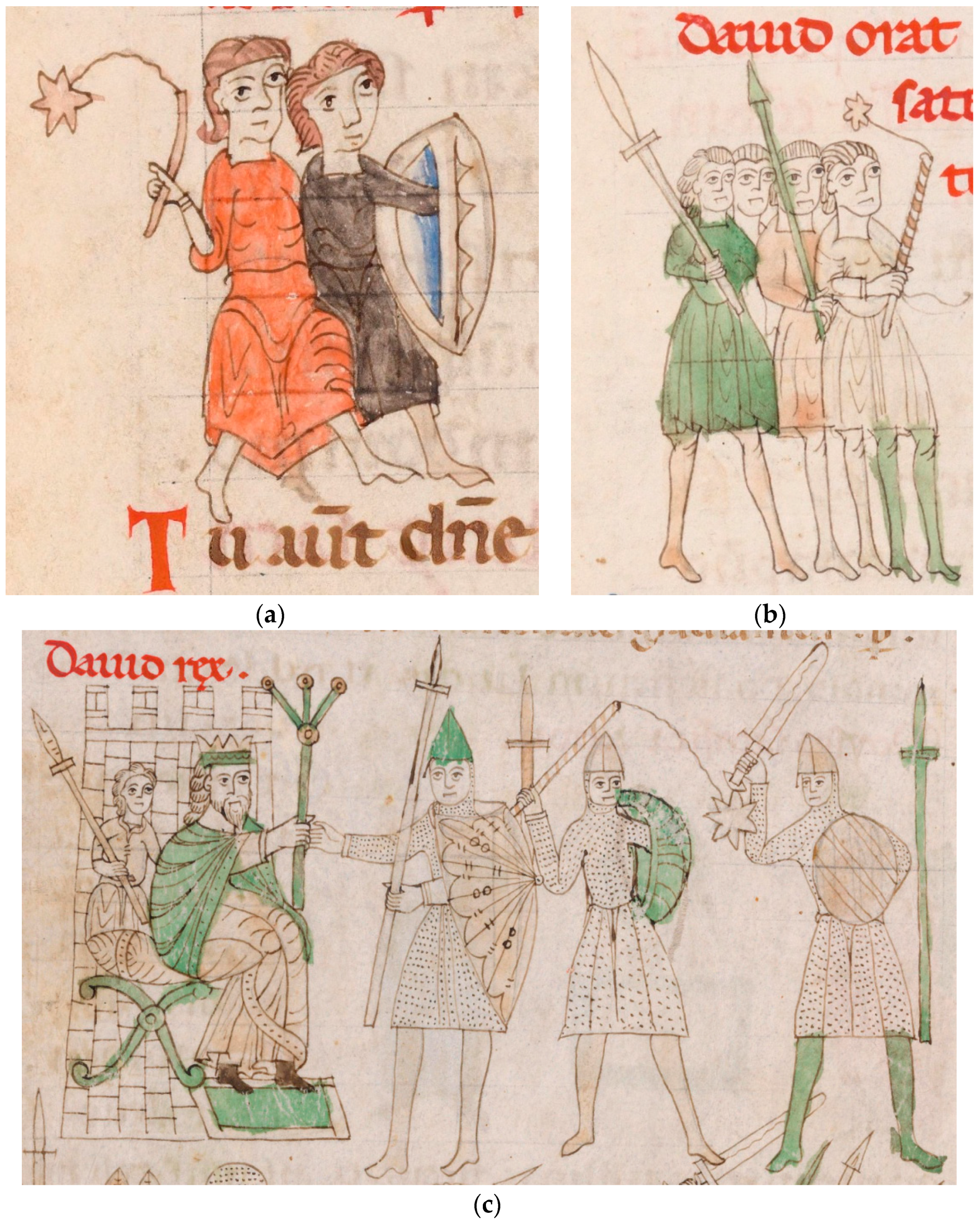

One of the more interesting medieval manuscripts depicting war flails is the Psalter Kupferstichkabinett 78 A 5 (Figure 21), believed to originate from northern Italy c. 1175, though now located in Berlin (Peterson 1987; Augustyn 1989). This piece depicts war flails in no fewer than three separate folios (fols. 10r, 45v, and 52r), one in the hands of a maille-armoured and shielded figure, and two in the hands of unarmoured figures. All three flails are depicted with spiked heads attached to the haft via a chain, though the proportions between the haft and chain are slightly variable across the depictions. Two of the depictions illustrate the haft with a spiral pattern running up it (in a similar manner to some warclub depictions in the Maciejowski bible), while the third is plainer in design. These folios depict various biblical scenes with a common thread of the old testament King David, who himself is not noted to be wielding the flail in any of the scenes.“S’i a fausars et quarriaus empenéEt pic et mache et coutiel afilé,Et dars molus avoit a grant plenté. (1305)III. grans plomees a deriere endossé,Puis prist se loke, e le vous adoubé.I. longement ot el chief saielé,Ja tant n’aroit tout le cors desmembré.”“Li Sarr. Avoit a sen costéLes .III. espees don’t I je vous ai conté.Se grant plomee’a d’encoste torséEt sen picois de brun achier tempréMiséricorde a çaint a sen costé; (2060)En sen dos furent si .m. hauberc saffre.”“Quant .R. vit celui escapéHors de le tiere, molt en est aïré.A se plomee avoit se main jeté (2270)Que bien pesoit .i. grant caisne ramé:IV diauble sont o lui empené.”

“Il ne portent o [avec] els ne lance ne espée,Mais gisarme esmolne et machu-e plomée,Li rois porte une faus qui moult bien est tempréeN’a paien si armé en tote la contréeK’il nel porfende tot desci qu’en la coréeMoult tient bien de sa gent la compaigne serrée,S’ont lor sas à lor cols à cordele torsée,Si ont les contés nus et les pances pelées,Les mustiax ont rostis et les plantes crevéesPar quel terre qu’il voisent moult gastent la contrée.”“They do not wield lance or swordBut gisarme (farming tool)… and flail (plomée)The King (of the Tafurs) carries a scythe which is well-soaked…”

“A blow, they give with three iron flails having seven chains triple-twisted, three-edged, with seven iron knobs at the end of every chain: each of them as heavy as an ingot of ten smeltings. Three big brown men. Dark equine backmanes on them, which reach their heels…… Three hundred will fall by them in their first encounter, and they will surpass in prowess every three in the Hostel; and if they come forth upon you, the fragments of you will be fit to go through the sieve of a corn-kiln, from the way in which they will destroy you with the flails of iron. Woe to him that shall wreak the Destruction, though it were only on account of those three! For to combat against ‘them is not a ‘paean round a sluggard.”

“D’une plomée va crestiens tuant,Ça .ii., ça .iii. les ala craventant.Et il s’escrient : « Aïde, Guiberz frans. (2685)« Sainte Marie ! ja serons recreant. »Guiberz l’oï, cele part vint corant,Et li paiens s’adrece vers l’enfant ;De sa plomée va la verje hauçantQue la mace ert par terre traïnant,Va la corroie larjement estendant”“With a plomée (flail) goes Crestiens killingFirst two thenIee, craving……from his plomée goes the heightening [strike?]As the mace (head) drags along the ground.”

A flail is described in the c. 1200 German poem Nibelungenlied or The Song of the Nibelungs which is believed to originate from Passau in the south of the modern-day Germany (Jähns 1899; Whobrey 2018; Shpakovsky and Nicolle 2013). The duel between the character Alberich (Albrich) and a “dwarf king” is described as follows (from a modern-day translation (full text available at https://www.gutenberg.org/files/7321/7321-h/7321-h.htm, accessed on 25 October 2023)):“Un flaiel porte, la mace ert d’orpuementEt tout li mances en estoit ensementEt la chaine don’t la batier pentPlain poig ert grosse, close estoit fierementKi ert molt dure, d’une pel de serpentKi ne crient arme d’acier ne ferrement.”“N’i a celui ne portast I flaelToz sont de coivre, bien over a cisel.”

The weapon described here is referred to as a giessel (whip) in the original text, though this seemingly describes a war flail, though a bit of artistic license on the part of the authors is likely here, unless the reference to gold is instead describing copper alloy in the form of brass or bronze which can appear golden. Most of the period depictions of war flails picture these with single heads, rather than the seven attested to in the poem, with multi-headed flails only appearing later (post 1250), barring a few exceptions previously highlighted. Shpakovsky and Nicolle postulate that the Germans viewed this as an alien weapon of some rarity in their locale, but nonetheless an awareness of the technology is demonstrated (Shpakovsky and Nicolle 2013). Late 13th century surviving versions of this work are extant and can be found https://www.digitale-sammlungen.de/en/view/bsb00035316?page=1, accessed on 25 October 2023.“Alberich was full wrathy,/thereto a man of power. (v. 494)Coat of mail and helmet/he on his body wore,And in his hand a heavy/scourge of gold he swung.Where was fighting Siegfried,/thither in mickle haste he sprung.Seven knobs thick and heavy/on the club’s end were seen, (v. 495)Wherewith the shield that guarded/the knight that was so keenHe battered with such vigor/that pieces from it brake.Lest he his life should forfeit/the noble stranger gan to quake.”

A 1202 inventory of weapons prepared after the capture of Robbio Castle (northern Italy) included, amongst other things, falciones (falchions/fauchards) and plumbatas (Kriegsflegels—war flails), though no further description than this is provided, and the original source (Angelucci Documenti) is unavailable (Köhler 1887).“Li uns pleut hache et li autres espec (3968)Li tiers sa mace et li quars sa plommée.”

“Dont li veissies pierres et pessemens ruer Et de lanches ferir et d espees caplerDe maches de plommees merveilleus cous donner”

Later Sources

“La véissiez enteser macesEt plomées pour faire plaies.”“La ot tant bastons et plomées.”

A small, single-headed ball-and-chain flail is depicted in a folio (049r, Figure 38) from the c. 1330–1340 illuminated French manuscript Avignon BM MS.121 Psalter-Hours in the hands of a maille-clad dark-skinned warrior who also bears a small round shield, perhaps a buckler. A number of similarly armoured figures wielding an assortment of polearms and a lantern are present in the background, perhaps mirroring the mob arresting Jesus in the 12th century frescoes presented above. The artist has chosen not to represent the wooden hafts of the various weapons present with brown pigment but instead coloured these in grey, as per the maille and steel or iron of the weapon heads, despite there being brown present in sword scabbards and hair. The flail depicted is one of the shorter examples known.“ayne payns ou gayns de baleyne sa espeye i. gladi’ & flagellű & galeam i. heaume.”“gaignepains or gauntlets of baleen, his espeye that is sword, and flail, and helm that is heaume.”

9. The Practical Use of Flails and their Context in Warfare in the Medieval Period

“We prohibit under anathema that murderous art of ballistariorum et sagittariorum, which is hateful to God, to be employed against Christians and Catholics from now on”

10. Discussion, Conclusions, and Further Work

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

Appendix A.1. Manuscript Images

Appendix A.2. Possibly Misidentified Archaeological Finds from the UK

Appendix A.3. Finds Sold at Auction

References

- Abad, Rubén Sáez. 2013. Atlas ilustrado de la Guerra en el Edad media en España. Spain: Suseaeta, p. 101. [Google Scholar]

- Agrigoroaei, Vladimir. 2018. Sacré et profane dans deux cathedrals du XIIe siècle. La context culturel de l’Artus de Modène et du Roland de Vérone. Francigena 4: 5–35. (In French) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alatas, Saadet Kaya. 2018. Administration de l’Etat et constitution de l’orthodoxie religieuse à Bagdad sous le vizirat de Nizâm-Al Mulk (1018–1092). Ph.D. thesis, University of Lyon, Lyon, France. Available online: https://theses.hal.science/tel-03292851 (accessed on 25 October 2023). (In French).

- Allmand, Christopher. 1999. War and the Non-Combatant in the Middle Ages. In Medieval Warfare: A History. Edited by Maurice Keen. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 264. [Google Scholar]

- Allmand, Christopher. 2011. The De Re Militari of Vegetius. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 148–96. [Google Scholar]

- Ames, Christine Caldwell. 2012. Medieval Religious, Religions, Religion. History Compass 10: 334–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrén, Anders. 2005. Behind Heathendom: Archaeological Studies of Old Norse Religion. Scottish Archaeological Journal 27: 105–38. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/27917543 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Antoche, Emanuel Constantin. 2004. Du tábor de jan zizka et de jean hunyadi au tabur çengi des armées ottomanes: L’art militaire hussite en Europe orientale, au Proche et au Moyen Orient (XVe-XVIIe siècles). Turcica 36: 91–124. (In French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnedo, Miguel Garcia. 2010. Guia de vestuario masculine Almogávaress: Siglos XII–XIII. Spain: Grupos de Recreación Histórica Medieval Amogávar, pp. 151–52. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Augustyn, Wolfgang. 1989. Zu Herkunft und Stil des lateinischen Hamilton-Psalters im Berliner Kupferstichkabinett (78 A5). Jahrbuch der Berliner Museen 31: 107–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4125853 (accessed on 25 October 2023). (In German). [CrossRef]

- Aveyard, Andrew George, Bradford Thomas Davison, Daniel Patrick Haggerty, and Jason Conrad Cardwell. 2014. Martial Arts of the Middle Age and Renaissance. Master’s thesis, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA. Available online: https://digital.wpi.edu/concern/student_works/fj2362645?locale=en (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Balbuena, Miguel Luis Poveda, and Jose Belda-Medina. 2022. The Effects of Multilingualism in Medieval England: The Impact of French on Middle English Military Terminology. In Bi- and Multilingualism from Various Perspectives of Applied Linguistics. Edited by Zofia Chłopek and Przemysław E. Gebal. Germany: V&R unipress/Brill, p. 67. [Google Scholar]

- Bánlaky, Jósef. 1928. A Magyar Nemzet Hadtortenelme. Hungary: Athenaeum. (In Hungarian) [Google Scholar]

- Bathgate, Ronald H. 1990. Hendrik Van Veldeke’s The Legend of St. Servaes Translated. Dutch Crossing 14: 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baxter, Ronald. 1987. A baronial bestiary: Heraldic evidence for the patronage of MS Bodley 764. Journal of the Warburg and Courtauld Institutes 50: 196–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beauchamp, Gorman. 1981. The dream of cockaigne: Some motives for the utopias of escape. The Centennial Review 25: 345–62. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23739084 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Beaud, Mathieu. 2017. Force et tempérance: Roland et Olivier gardiens du portail du duomo de Vérone. Paper presented at Le combatant à l’époque romane, 27e colloque international d’art roman d’Issoire, France, October 20–21. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Beňa, Samuel. 2014. The Small War in the Late Middle Ages: A Comparison of the English and Bohemian Experiences. Master’s thesis, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. Available online: http://www.etd.ceu.hu/2014/bena_samuel.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Biederman, Jan. 2014. L’art militaire dans les ordonnances tchèques du XVe siècle et son évolution: La doctrine du Wagenburg comme résultat de la pratique. Médiévales 67: 69–82. (In French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bollard, John K. 1994. Arthur in the Early Welsh Tradition. In The Romance of Arthur: An Anthology of Medieval Texts in Translation. Edited by Norris Lacy and James Wilhelm. London: Routledge, pp. 14–16. [Google Scholar]

- Bouwman, André, and Bart Besamusca. 2009. Of Reynart the Fox. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, pp. 84–85. [Google Scholar]

- Bradbury, Jim. 1990. Geoffrey V of Anjou, Count and Knight. In The Ideals and Practice of Medieval Knighthood III: Papers from the Fourth Strawberry Hill Conference, 1988. Edited by Christopher Harper-Bill and Ruth Harvey. Martlesham: Boydell and Brewer. [Google Scholar]

- British Library Catalogue. n.d. Yates Thompson Manuscripts. Available online: http://hviewer.bl.uk/IamsHViewer/FindingAidHandler.ashx?recordid=032-002354332 (accessed on 26 October 2023).

- Brooks, Shad M. 2019. Overappreciated Historical Weapons: The Medieval FLAIL. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ox4sCJnCpzo (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Brown, Arthur C. L. 1919. The Grail and the English Sir Perceval. Modern Philology 16: 553–68. Available online: https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/387224 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Burgers, Jan W. J. 1998. Eer en schande van Floris V. Twee oude twistpunten over de geschiedenis van een Hollandse graaf. Holland 30: 1–21. (In Dutch). [Google Scholar]

- Buridant, Claude. 2003. La ‘traduction intralinguale’ en moyen fran~ais a travers la modernisation et Ie rajeunissement des textes manuscrits et imprimes: Quelques pistes et perspectives. Le Moyen Francais 51: 113–57. (In French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campagnano, Gabriele. 2015. Armi immanicate da botta (II): Il Mazzafrusto. Available online: https://zweilawyer.com/2015/05/31/armi-immanicate-da-botta-ii-il-mazzafrusto/ (accessed on 27 October 2023). (In Italian).

- Carey, Brian Todd, Joshua B. Allfree, and John Cairns. 2006. Warfare in the Medieval World. Barnsley: Pen and Sword. [Google Scholar]

- Carley, Lionel K. 1962. A Thirteenth Century Translation of the “De Re Militari” of Flavius Vegetius Renatus. Ph.D. thesis, University of Nottingham, Nottingham, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, Martin O. H. 1986. V. Contemporary Artefacts Illustrated in Late Saxon Manuscripts. Archaeologia 108: 117–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cazanave, Caroline. 2013. La fin de vie de Guillaume de Gellone/Guillaume d’Orange: Des Moniages en vers au de Louis Gabriel-Robinet roman historique. Les Grandes figures historiques dans les Lettres et les Arts 2: 61–100. Available online: https://figures-historiques-revue.univ-lille.fr/category/2-2013/ (accessed on 25 October 2023). (In French). [CrossRef]

- Church, Alfred John. 1904. Stories of Charlemagne and the Twelve Peers of France: From the Old Romances. New York: Macmillan, pp. 349–50. [Google Scholar]

- Civil, Miguel. 1963. Sumerian Harvest Time. Expedition Magazine 5: 4. Available online: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/sumerian-harvest-time/ (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Clemmensen, Steen. 2013. Jörg Rugens Wappenbuch. Innsbruck: Universitäts- und Landesbibliothek Tirol. [Google Scholar]

- Comfort, William W. 1914. Arthurian Romances. London: Everyman’s Library. [Google Scholar]

- Constans, Léopold Eugène. 1890. Le Roman de Thèbes. Paris: Librairie de Firmin Didot. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Costa, Anotonio Luiz M. C. 2015. Armas Brancas. Sao Paolo: Draco. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Courville, Cyril B. 1948. War Weapons as an Index of Contemporary Knowledge of the Nature and Significance of Craniocerebral Trauma: Some Notes on Striking Weapons des Igned Primarily to Produce Injury to the Head. Medical Arts and Sciences: A Scientific Journal of the College of Medical Evangelists 2: 85–111. Available online: https://scholarsrepository.llu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1036&context=medartssciences (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Cowper, H. S. 1906. The Art of Attack. Ulverston: Holmes. [Google Scholar]

- Culic, Dan. 2016. Living Among Ruins: The Medieval Habitat in the Ancient Settlement of Porolissum and in its Surroundings. Journal of Ancient History and Archaeology 3: 31–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cuming, Henry Syer. 1854. On Irish Antiquities. Journal of the British Archaelogical Association 10: 165–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amato, Raffaele. 2005. A Prôtospatharios, Magistros, and Strategos Autokrator of 11th cent.: The equipment of Georgios Maniakes and his army according to the Skylitzes Matritensis miniatures and other artistic sources of the middle Byzantine period. Porhyra 4: 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- D’Amato, Raffaele. 2011. The War-mace of Byzantium, 9–15 C. ad New Evidence from the Balkans in the Collection of the World Museum of Man, Florida. Acta Militaria Medievalia 7: 7–48. [Google Scholar]

- Dahm, Murray. 2018. Medieval Warfare on Film II. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/35767957/Medieval_Warfare_on_Film_II (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- Daniel, Norman. 1979. The Arabs and Medieval Europe. London: Longman. [Google Scholar]

- Daubney, Adam. 2007. Medieval Copper-alloy Mace-heads from England, Scotland and Wales. In A Decade of Discovery: Proceedings of the Portable Antiquities Scheme Conference 2007. Oxford: British Archaeological Reports, pp. 194–200. [Google Scholar]

- Davies, Helen. 2020. Multispectral Imaging of the Vercelli Mappamundi: A Progress Report. The International Journal for the History of Cartography 72: 181–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Day, Jennifer Penelope. 2010. Arfau yn yr Hengerdd a Cherddi Beirdd y Tywysogion. Ph.D. thesis, University of Aberystwyth, Aberystwyth, Wales, UK. (In Welsh). [Google Scholar]

- de Boislisle, Jean. 1943. Léon Lecestre (1861–1941). Bibliothèque de l’école des chartes 104: 384–88. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- de France, Marie. 1820. Poésies de Marie de France, poète anglo-normand du XIIIe siècle, ou Recueil de lais, fables et autres productions de cette femme célèbre: Publiées d’après les manuscrits de France et d’Angleterre, avec une notice sur la vie et les ouvrages de Marie; la traduction de ses Lais en regard du texte, avec des notes, des commentaires, des observations sur les usages et coutumes des François et des Anglois dans les XIIe et XIIIe siècles. 1 vol. Paris: Chasseriau, p. 439. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- de Lage, Guy Raynaud. 1966. Roman de Thèbes. Paris: Champion, pp. 7, 58. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Demmin, Auguste. 1911. An Illustrated History of Arms and Armour: From the Earliest Period to the Present Time. London: Bell, pp. 424–26. [Google Scholar]

- Denny, Don. 1984. The Date of the Conques Last Judgment and its Compositional Analogues. The Art Bulletin 66: 1, 7–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deschamps, Paul. 1941. Les sculptures de l’église Sainte-Foy de Conques et leur décoration peinte. Monuments et Memoires de la Fondation Eugene Piot 38: 156–85. (In French). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devereaux, Bret. 2019. Collections: The Siege of Gondor, Part V: Just Flailing About Flails. Available online: https://acoup.blog/2019/06/07/collections-the-siege-of-gondor-part-v-just-flailing-about-flails/ (accessed on 27 October 2023).

- DeVries, Kelly Robert, and Robert Douglas Smith. 2012. Medieval Military Technology. Toronto: University of Toronto Press, pp. 28–30. [Google Scholar]

- Dona, Carlo. 2021. Nicholaus e i due eroi del protiro di Santa Maria Matricolare: Dalla tradizione epica al Tempio di Salomone. Francigena 7: 7–88. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Dougherty, Martin J. 2008. Weapons and Fighting Techniques of the Medieval Warrior: 1000–1500 AD. New York: Metro, p. 91. [Google Scholar]

- Doyle, Clodagh, Paul Doyle, Tom Doyle, Vivian Lynn, Séamas Mac Philib, Rosa Meehan, Deirdre Power, and Albert Siggins. n.d. Guide to the National Museum of Ireland: Country Life. Mayo: National Museum of Ireland, p. 30.

- Drob, Ana, and Viorica Vasilache. 2022. Investigația non-invazivă a unei arme medievale din bronz descoperite în podu-iloaiei—Șesul târgului, jud. iași. Arheologia Moldovei 45: 219–26. (In Romanian). [Google Scholar]

- du Parc, J. C. 1884. La Mort Aymeri de Narbonne: Chanson de Geste. Paris: Fermin Didot. Available online: https://gallica.bnf.fr/ark:/12148/bpt6k97721205 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Eberhart, Christian A. 2005. The “Passion” of Gibson: Evaluating a recent interpretation of Christ’s suffering and death in light of the New Testament. Consensus 30: 37–74. Available online: https://scholars.wlu.ca/consensus/vol30/iss1/4/ (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Edbury, Peter. 2016. Ernoul, Eracles and the Fifth Crusade. In The Fifth Crusade in Context. Edited by Elizabeth J. Mylod, Guy Perry, Thomas Smith and Jan Vandeburie. London: Routledge, p. 172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Edwards, Daniel. 2019. Finance and the Crusades: England, c.1213–1337. Ph.D. thesis, Royal Holloway University of London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Eley, Penny. 2011. Partonopeus de Blois: Romance in the Making. Woodbridge: Brewer, p. 86. [Google Scholar]

- Erisman, Wendy. n.d. Canting arms: A Comparison of Two Regional Styles: Gwenllian Ferch Maredudd. Available online: https://www.ellipsis.cx/~liana/latex/kw/gwenllian/gwenllian.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Escobar, Robert. 2018. Saps, Blackjacks and Slungshots: A History of Forgotten Weapons. Columbus: Catoblepas. [Google Scholar]

- Esposito, Davide. 2018. L’universo ideologico della Chanson de Jérusalem Mentalità e propaganda crociata nel XII secolo. Ph.D. thesis, University of Naples, Naples, Italy. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Farcas, Andrei-Octavian. 2016. Maces in Medieval Transylvania between the Thirteenth and Sixteenth Centuries. Master’s thesis, Central European University, Budapest, Hungary. [Google Scholar]

- Faulliot, Pascal. 1982. El Blanco Invisible. Barcelona: Teorema. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Fee, Christopher. 2018. Arthur: God and Hero in Avalon. Clerkenwell: Reaktion, p. 59. [Google Scholar]

- Fein, Susanna Greer, and David Raybin. 2019. The Anglo-Norman Otinel. In The Roland and Otuel Romances and the Anglo-French Otinel. Edited by Elizabeth Melick, Susanna Fein and David Raybin. Kalamazoo: Medieval Institute Publications. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferlampin-Acher, Christine. 2007. Le Roman de Thèbes, geste de deus freres: Le roman et son double. In Romans d’antiquité et littérature du Nord. Edited by Sarah Baudelle-Michels, Marie-Madeleine Castellani and Philippe Logié et Emmanuelle Poulain-Gautret. Paris: Champion, pp. 309–18. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes, David Jose Cordeiro. 2019. Veracidad Histórica (o su ausencia) en el Armamento de chivalry: Medieval Warfare. Master’s thesis, University of Murcia, Murcia, Spain. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Florek, Marek. 2019. A Weight, a Mace Head, a War-Flail, or Something Else? A Contribution to Studies on the Function of some early Medieval Artefacts. Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 15: 101–7. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Frutos, Alberto Montaner. 2019. Materiales para una poética de la Imaginación emblemática. Emblemata: Revista aragonesa de emblemática 25: 25–184. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Funck-Brentano, Frantz. 1922. Le Moyen Âge. New York: Hachette. [Google Scholar]

- Gallardo, José Maria. 2016. ¿Existió el llamado en castellano mangual o mayal (‘flail’ en inglés), un arma de una mano medieval y fue usado en combate real? SÍ. Un ejemplo de “polémica barata a través de internet” en el mundo popular y académico. Available online: https://handlingthosebastards.wordpress.com/2016/06/05/existio-el-llamado-en-castellano-mangual-o-mayal-flail-en-ingles-un-arma-de-una-mano-medieval-y-fue-usado-en-combate-real-si-un-ejemplo-de-polemica-barata-a-traves-de-internet/ (accessed on 27 October 2023). (In Spanish).

- Geldof, Mark Ryan. 2015. “And to describe the shapes of the dead”: Making Sense of the Archaeology of Armed Violence. In Wounds and Wound Repair in Medieval Culture. Edited by Larissa Tracy and Kelly DeVries. Amsterdam: BRILL, p. 66. [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardinger, Maria Elisabetta. 2020. A proposito dell’affresco staccato con episodi de La chanson d’Otinel, Attività & Ricerche. Attività & Ricerche, Bollettino Dei Musei E Degli Istituti Ella Cultura Della Città Di Treviso 1: 75–85. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Gerhardt, Christoph. 2007. In vero iudicio fecisti. Eine historisierte O-Initiale im ‚Corvinus-Graduale‘. In vero iudicio fecisti. Eine historisierte O-Initiale im‚ Corvinus-Graduale‘, in: Rund um den Dom: Kleine Beiträge zur Geschichte der Trierer Bücherschätze. Edited by Karl-Heinz Hellenbrand, Wolfgang Schmidt and Rainer Schwindt. Trier:: Trier University Library, pp. 48–63. (In German) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibbs, Marion, and Sidney M. Johnson. 1997. Medieval German Literature. Oxford: Routledge, pp. 195–96. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzalez, Antonio Rodríguez. 2013. Feudalismo en las Antípodas: Comparación entre un caballero medieval europeo y un guerrero samurai. Kokoro: Revista para la difusión de la cultura japonesa 13: 2–23. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Gordon, Stephen. 2019. Supernatural Encounters: Demons and the Restless Dead in Medieval England, c. 1050–1450. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Górski, Szymon, and Ewelina Wilczyńska. 2012. Jan Žižka’s wagons of war. Medieval Warfare 2: 27–34. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48578020 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Gotzinger, Ernst. 1885. Reallexikon der deutschen Altertümer. Munich: Urban, p. 493. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Grabarczyk, Tadeusz. 2000. Plebeian Weapons in the Armaments of the Enlisted Infantry in the Years 1471–1500. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 12: 9–13. [Google Scholar]

- Grant, Neil. 2020. The Medieval Longsword. London: Bloomsbury, p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Green, Alice Stopform. 1888. Henry the Second. New York: Macmillan, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Gregory, Isabella A. 1905. Gods and Fighting Men. London: John Murray. [Google Scholar]

- Grotowski, Piotr. 2010. Arms and Armour of the Warrior Saints: Tradition and Innovation in Byzantine Iconography (843–1261). Lieden: BRILL, p. 28. [Google Scholar]

- Gug, Rémy. 1986. The Proportioial Compass: A mathematical instrument at the disposal of the old instrument makers. FOMRHI Quarterly (Original In French). 43: 71–86. [Google Scholar]

- Hahn, Cynthia. 1991. Peregrinatio et Natio: The Illustrated Life of Edmund, King and Martyr. Gesta 30: 119–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamburger, Jeffrey F. 1991. A Liber Precum in Sélestat and the Development of the Illustrated Prayer Book in Germany. The Art Bulletin 73: 209–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamilton, Theodore Ely. 1911. The Cyclic Revelations of the Chanson of Willame. Columbia: Stephens, p. 163. [Google Scholar]

- Havard, Oscar. 1876. Le Moyen Age et Ses Institutions. Paris: Mameet Fils. [Google Scholar]

- Hegg, Victor. 2021. English and Norwegian Military Legislation in the 13th Century—The Assize of Arms and Norwegian Military Law. Master’s thesis, University of Bergen, Bergen, Norway. [Google Scholar]

- Herrera, Alejandro Sánchez. 2014. Evolución militar y componentes del ejército en Japón entre el s.IX y el s.XVII. Master’s thesis, University of Seville, Seville, Spain. (In Spanish). [Google Scholar]

- Herron, Thomas. 2002. The Spanish Armada, Ireland, and Spenser’s The Faerie Queene. New Hibernia Review 6: 82–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hewitt, John. 1855. Ancient Armour and Weapons in Europe: From the Iron Period of the Northern Nations to the End of the Thirteenth (-Seventeenth) Century. 1 vol. London: Henry and Parker. [Google Scholar]

- Hill, David. 1998. Eleventh century Labours of the Months in Prose and Pictures. Landscape History 20: 29–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillaby, Joe. 2004. The Origins and Evolution of the Medieval Ground Plan of Leominster Borough. Transactions of the Woolhope Naturalists’ Field Club 52: 11–56. [Google Scholar]

- Homans, George Caspar. 1941. English Villagers of the Thirteenth Century. Harvard: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hosler, John D. 2014. The ‘Golden Age of Historiography’: Records and Writers in the Reign of Henry II. History Compass 12: 398–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosler, John D. 2017. Chivalric Carnage? Fighting, Capturing and Killing at the Battles of Dol and Fornham in 1173. In Prowess, Piety, and Public Order in Medieval Society. Edited by Craig M. Nakashian and Daniel P. Francke. Lieden: BRILL, p. 51. [Google Scholar]

- Hrynchyshyn, B. V. 2014. Medieval Bladed Weapons in the Figurative Sources. Bulletin of the Lviv Polytechnic National University 809: 13–16. [Google Scholar]

- Huet, G. 1912. Lancelot en prose et Méraugis de Portlesguez. Romania 41: 518–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hull, Jeffrey. 2007. Fight Earnestly. Available online: https://www.academia.edu/1421063/Fight_Earnestly_Fight_Book_by_Hans_Talhoffer_1459_Thott_ (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Hyams, Paul R. 1970. The Origins of a Peasant Land Market in England. Economic History Review 23: 18–31. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2594561 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Imiolczyk, Ewelina, and Radosław Zdaniewicz. 2022. A find of a bronze macehead from the kraków-częstochowa upland in poland. Fasciculi Arcaeologiae Historicae 35: 147–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Impey, Edward. 2019. ‘A desperat wepon’: Re-hafted scythes at sedgemoor, in warfare and at the tower of london. The Antiquaries Journal 99: 225–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izdebska, Daria. 2016. Metaphors of Weapons and Armour Through Time. In Mapping English Metaphor Through Time. Edited by Wendy Anderson, Ellen Bramwell and Carole Hough. Oxford: Oxford University Press, p. 22. [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs, Jospeh. 1892. Celtic Folk and Fairy Tales. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Jähns, M. 1880. Handbuch einer Geschichte des Kriegswesens von der Urzeit bis zur Renaissance: Technischer Theil: Bewaffnung, Kampfweise, Befestigung, Belagerung, Seewesen. 1 vol. Leipzig: Grunow. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Jähns, M. 1899. Entwicklungsgeschichte der alten Trutzwaffen: Mit einem Anhange über die Feuerwaffen. Germany: Mittler, pp. 200–2. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- James, Montague R. 1925–1926. The Drawings of Matthew Paris. The Volume of the Walpole Society 14: 1–26. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/41830691 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Jócsik, Kristián. 2022. Stav Bádania a Perspektívy Výskumu Staromaďarských Jazdeckých Hrobov. Master’s thesis, University of Nitra, Hungary. (In Hungarian). [Google Scholar]

- Kahn, Deborah. 1997. La Chanson de Roland dans le décor des églises du XIIe siècle. Cahiers de Civilisation Medievale 46: 337–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katona, Csete. 2017. Vikings in Hungary? The Theory of the Varangian-Rus’ Bodyguard of the First Hungarian Rulers. Viking and Medieval Scandinavia 13: 23–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kennedy, Patrick. 1866. Legendary Fictions of the Irish Celts. London: Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kirpičnikov, Anatoly N. 1966. Drevnerusskoe oruzhie. Vyp. 2. Kop’ia, sulitsy, boevye topory, bulavy, kisteni IX-XIII vv. Arkheologiia SSSR. Svod arkheologicheskikh istochnikov E1-36. Corpus of Archaeological Sources, 1–36. (In Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Kirpičnikov, Anatoly N. 1968. Die Russische Waffen des 9–13 Jahrhunderts und orientalische und westeuropaische Einflusse auf ihre Entwicklung. Gladius 7: 45–74, (In German, translated from Russian). [Google Scholar]

- Kirpičnikov, Anatoly N. 1970. Die Feldschlacht in altrussland (IX-XIII Jh.). Gladius 9: 31–51, (In German, translated from Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knapp, Fritz Peter. 2013. Aliscans. Berlin: DeGuyter. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Köhler, Gustav. 1887. Die Entwickelung des Kriegswesens und der Kriegführung in der Ritterzeit von Mitte des 11. Jahrhunderts bis zu den Hussitenskriegen. Germany: Koebner. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Kolar, Aidan. 2020. Church Construction and Urbanism in Byzantine North Africa. Master’s thesis, Univeristy of Oregon, Eugene, OR, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Köstler, Karl. 1883. Die Ungarnschlacht auf dem Lechfelde am 10. August 955 und die Folgen der Ungarnkriege uberhaupt. Bonn: Schulze, pp. 7–8. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Kotowicz, Piotr N. 2006. Uwagi O Znaleziskach Kiścieni Wczesnośredniowiecznych Na Obszarze Polski. Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 2: 51–66. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Kotowicz, Piotr N. 2008. Early medieval war-flails (kistens) from Polish lands. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 51: 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowicz, Piotr N., and Arkadiusz Michalak. 2007. Status of Research on Early-Medieval Armament in Małopolska. Remarks regarding the Monograph Study by P. Strzyż. Acta Archaeologica Carpathica 52–53: 337–82. [Google Scholar]

- Kotowicz, Piotr N., and Paweł Skowroński. 2020. Changes in Military Equipment during the 13th and 14th Centuries in the Area of the Sanok Land. Fasciculi Archaeologiae Historicae 33: 49–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kristo, Mateo. 2020. l Bektashismo nei Balcani fra fede e nazionalismo Storia dell’Islam “nascosto” nell’Europa sud-orientale. Master’s thesis, University of Torino, Turin, Italy. (In Italian). [Google Scholar]

- Kuleshov, Yuri A. 2019. Combat Flails In The Armament Of The Golden Horde. Golden Horde Rev 7: 37–54. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- L’Engle, Susan. 2002. Justice in the Margins: Punishment in Medieval Toulouse. Viator 33: 133–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ławrynowicz, Olgierd, and Piotr A. Nowakowski. 2008. Stove tiles as a source of knowledge about medieval and Early Modern arms and armour. Studies in Post-Medieval Archaeology 3: 303–16. [Google Scholar]

- Le Roux de Lincy, Antoine. 1836. Le Roman de Brut, par Wace, poète du XIIe siècle, publié pour la première fois. Paris: Frere, p. 147. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Leon, Enrique. 2019. La Bataille de Bouvines. Histoire et légendes by Dominique Barthélemy. Revue Historique 689: 140–43. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/10.2307/26782495 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Lepage, Jean-Denis G. G. 2005. Medieval Armies and Weapons in Western Europe. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Lewy, Mordechay. 2021. The French King and the Ostrich: Reflections on the Date of the Medieval Vercelli Map of the World. Imago Mundi 73: 64–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindsey, Gwendolyn Sweezey. 2005. Using the Design Process as a Model for Writing a Guide to Making Maille Armour. Master’s thesis, University of Akron, Akron, OH, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Lipton, Sara. 1999. Violence and Daily Life: Reading, Art, and Polemics in the Cîteaux Moralia in Job by Conrad Rudolph. Journal of the American Academy of Religion 67: 703–6. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/1466227 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Lofmark, Carl. 1972. Rennewart in Wolfram’s ‘Willehalm’: A Study of Wolfram Von Eschenbach and His Sources. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, p. 159. [Google Scholar]

- Mac Coitir, Niall. 2020. The vernacular uses of Irish wood. Irish Forestry 77: 94–105. [Google Scholar]

- Macculloch, John Arnott. 1916. The Mythology of All Races in Thirteen Volumes:Celtic. Boston: Marshall Jones, p. 183. [Google Scholar]

- Mäesalu, Ain. 2004. Kaitserüüde arendamise põhjustest 13. –17. Sajandil. Muinasaja Teadus 14: 227–48. (In Estonian). [Google Scholar]

- Maher, Martina. 2018. The Death of Finn mac Cumaill. Ph.D. thesis, University of Glasgow, Glasgow, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Mamontov, Vladislav I. 2018. On the Weapons Used by Sarmatians in Close Combats. Science Journal of Volgograd State University. History. Area Studies. International Relations 23: 153–58. (In Russian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manning, Scott. 2016. The Case Against the Medieval Ball and Chain. Available online: https://scottmanning.com/content/the-case-against-the-medieval-ball-and-chain/ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Markowitz, Mark. 2021. Weapons on Ancient Coins. Available online: https://coinweek.com/ancient-coins/weapons-on-ancient-coins/ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- McCulloch, Lynsey. 2011. Antique Myth, Early Modern Mechanism: The Secret History of Spenser’s Iron Man. In The Automaton in English Renaissance Literature. Edited by Wendy Beth Hyman. Farnham: Ashgate, pp. 61–76. [Google Scholar]

- McDougall, David Macmillan. 1983. Studies in the Prose Style of the Old Icelandic and Old Norwegian Homily Books. Ph.D. thesis, University College London, London, UK. Available online: https://discovery.ucl.ac.uk/id/eprint/1381762/ (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- McDowell, Gavin. 2007. Double Indignity: Two Tales in Chretien de Troyes’s Perceval. In Fresh Writing. Edited by Connie Snyder Mick and Michael Subialka. Plymouth: Hayden McNeil, p. 134. [Google Scholar]

- McLachlan, Sean. 2011. Medieval Handgonnes: The First Black Powder Infantry Weapons. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Meneghetti, Maria Luisa. 1990. Une Trace De La «Chansbn De Roland» En Arménie? Memorias de la Real Adademia de Buenas Letras de Barcelona 22: 67–80. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Michalak, Arkadiusz. 2006. Jeszcze o buławach średniowiecznych z ziem polskich refleksje na marginesie odkrycia z bogucina, pow. Olkusz. Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 2: 103–14. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Michalak, Arkadiusz. 2019. On Throwing Maces Yet Again. Acta Archaeologiae Militaris 5: 133–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, Arkadiusz, and Kinga Zamelska-Monczak. 2016. Czy Xii-Wieczny Ciężarek Z Poroża Z Santoka Jest Elementem Kiścienia? Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 12: 199–206. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Michalak, Arkadiusz, and Piotr Wolanin. 2008. Skóra w służbie wojny. Militarne i pozamilitarne, skórzane elementy wyposażenia wojownika w średniowieczu. Przegląd problematyki. Acta Archaeologca 54: 99–120. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=244148 (accessed on 28 October 2023). (In Polish).

- Mitchell, Piers D. 2002. Trauma and Surgery in the Crusades to the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean. Ph.D. thesis, University College London, London, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Mittman, Asa Simon. 2019. The Vercelli Map (c. 1217). In A Critical Companion to English Mappae Mundi of the Twelfth and Thirteenth Centuries. Edited by Dan Terkla and Nick Millea. Rochester: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Moffat, Ralph. 2010. The Manner of Arming Knights for the Tourney: A Re-Interpretation of an Important Early 14th-Century Arming Treatise. Arms and Armour 7: 5–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mondschein, Ken. 2017. Game of Thrones and the Medieval Art of War. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Monfrin, Jacques. 1965. Périodiques. Romania 86: 414–24. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/45038644 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Mora-Lebrun, Francine. 1995. Le Roman de Thebes: Edition du manuscrit S. London: British Library. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno, Jesús Ruiz. 2015. Armas de Percusion Articuladas. Historia Rei Militaris 8: 81–88. [Google Scholar]

- Morey, Charles R. 1931. The Vatican Terence. Classical Philology 26: 374–85. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/265109 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Mosca, Elisa. 2020. La veïssiés fier estor et pesant. La tecnica d’urto frontale nella narrativa eroica d’oïl. Master’s thesis, University of Padova, Padova, Italy. [Google Scholar]

- Myrdal, Janken. 1997. The agricultural transformation of Sweden, 1000–1300. In Medieval Farming and Technology: The Impact of Agricultural Change in Northwest Europe. Edited by Grenville Astill and John Langdon. Lieden: BRILL, p. 164. [Google Scholar]

- Needham, Joseph. 1959. The Wilkins Lecture: The missing link in horological history: A Chinese contribution. Proceedings of the Royal Society A 250: 147–79. [Google Scholar]

- Négyesi, Lajos. 2003. Az augsburgi csata. Hadtörténelmi Közlemények 1: 206–30. Available online: https://militaria.hu/hadtorteneti-intezet-es-muzeum/hadtortenelmi-kozlemenyek-letoltes/2003.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Newman, P. R. 1985. The Flail, the Harvest and Rural Life. Folk Life 24: 170–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicolle, David C. 1999. Arms and Armour of the Crusading Era 1050–1350: Western Europe and the Crusader. London: Greenhill, pp. 118, 130. [Google Scholar]

- Nicolotti, Andrea. 2017. The Scourge of Jesus and the Roman Scourge. Journal for the Study of the Historical Jesus 15: 1–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Niewiński, Andrzej. 2019. Inter arma enim silent leges (In times of war, the laws fall silent). Violence in Medieval warfare. Teka Komisji Historycznej 1: 9–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilsson, Skallagrim. 2021. Military Flails Didn’t Exist?—Let’s Take a Closer Look. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0PHASxS8Voc (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Norris, Pauline. 2015. The Lettuce Connection a Re-Examination of the Association of the Egyptian God Min with the Lettuce Plant from the Predynastic to the Ptolemaic Period. Ph.D. thesis, University of Manchester, Manchester UK. [Google Scholar]

- O’Bryan, John. 2013. A History of Weapons. San Francisco: Chronicle, pp. 152–53. [Google Scholar]

- O’Hogain, Dáithí. 1986. Magic Attributes of the Hero in Fenian Lore. Béaloideas 54–55: 207–42. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/20522287 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Oakeshott, Ewart. 2012. European Weapons and Armour from the Renaissance to the Industrial Revolution. Martlesham: Boydell Press. [Google Scholar]

- Oman, Charles. 1898. A History of the Art of War. New York: Putnam & Sons, p. 397. [Google Scholar]

- Ortiz, Manuel Valle. 2016. The Destreza Verdadera: A Global Phenomenon. In Late Medeival and Early Modern Fight Books. Edited by Daniel Jaquet, Karin Verelst and Timothy Dawson. Lieden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Osgood, Richard. 2005. The Unknown Warrior: The Archaeology of the Common Soldier. Cheltenham: The History Press. [Google Scholar]

- Osypenko, Maksim. 2019. METAЛEBi KИCTEHi ДABHЬOPУCЬKOÏ ДOБИ (зa мaтepiaлaми Haцioнaльнoгo мyзeю icтopiї Укpaїни). Arheologia 4: 72–89. (In Ukrainian). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Osypenko, Maksim. 2020. POГOBI KИCTEHI XI–XIII CT. ЗA MATEPIAЛAMИ HAЦIOHAЛЬHOГO MУЗEЮ ICTOPIÏ УKPAÏHИ. Hayкoвий вicник Haцioнaльнoгo мyзeю icтopiї Укpaїни 6: 63–71. (In Ukrainian). [Google Scholar]

- Palgrave, Francis. 1864. The History of Normandy and of England. 3 vols. London: MacMillan, pp. 36, 104. [Google Scholar]

- Papaioannou, Athanasios. 2019. Horse and Horsemen on Classical and Hellenistic Coins in Thessaly. Master’s thesis, International Hellenic University, Thessalonica, Greece. [Google Scholar]

- Paron, Aleksander. 2021. “War is part of their nature”: Nomadic violence in Byzantine texts of the 10th to 12th century—A tool of identity and… policy-making. Quaestiones Medi Aevi Novae 26: 5–31. Available online: https://www.ceeol.com/search/article-detail?id=1007048 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Perratore, Julia. 2015. The saint above the door: Hagiographic sculpture in twelfth-century Uncastillo. Journal of Medieval Iberian Studies 9: 72–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peterson, Elizabeth Anne. 1987. Accidents and Adaptations in Transmission among Fully-Illustrated French Psalters in the Thirteenth Century. Zeitshrift fur Kunstgeschichte 50: 375–84. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/1482386 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Phillip, Filiz Cakir. 2019. The Battle Flail—A Differentiating Feature of The Turk. Paper presented at 16th International Congress of Turkish Arts, Ankara, Turkey, October 3–5. [Google Scholar]

- Planché, James Robinson. 1876. A Cyclopaedia of Costume. 1 vol. London: Chatto and Windus, pp. 190–92. [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, Monika. 2004. Untersuchungen zur Darstellung mittelalterlicher Herrscher in der deutschen Kaiserchronik des 12. Jahrhunderts. Ein Werk im Umbruch von mündlicher und schriftlicher Tradition. Ph.D. thesis, Ludwig-Maximilians-Universität München, Munich, Germany. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Popov, Stoyan, and J. Aladjov. 2016. A Kisten (War-Flail) with Iyi–Sign From Bulgaria. Bocтoчнaя Eвpoпa в дpeвнocти и cpeднeвeкoвьe 28: 241–44. [Google Scholar]

- Power, Eileen. 1940. Review: Medieval England. The Economic History Review 10: 155–58. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/2590795 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Puziuk, Jakub, and Anna Tyniec. 2013. Buławy średniowieczne z ul. Sławkowskiej 17 w Krakowie. Materiały Archeologiczne 39: 33–53. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Rabillon, Léonce. 1885. La Chanson de Roland. New York: Holt. [Google Scholar]

- Rabovyanov, Deyan. 2021. The use of war-flails in the Bulgarian lands during the Byzantine conquest period—Archaeological evidence from the northern borders of the empire. In War in Eleventh-Century Byzantium. Edited by Georgios Theotokis and Marek Mesko. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Radtchenko, Daria. 2006. Simulating the past: Reenactment and the quest for truth in Russia. Rethinking History 10: 127–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raffel, Burton. 1999. Perceval: The Story of the Grail. New Haven: Yale, p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Rageth, Jürg, and Werner Zanier. 2010. Crap Ses und Septimer: Archäologische Zeugnisse der römischen Alpeneroberung 16/15 v. Chr. aus Graubünden. Mit einem Beitrag von Sabine Klein. Germania 88: 241–83. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Ridley, Florence H. 1992. Attila the Hun and King Arthur: A Question of Affinities. Florilegium 11: 101–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Riquer, Martin de. 1968. L’arnès del cavaller: Armes i armadures catalanes medieval. Barcelona: Edicions Ariel. (In Catalan) [Google Scholar]

- Robinson, E. S. G. 1933. Coins of Thessaly. The British Museum Quarterly 8: 49–50. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/4421548 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Rudolph, Conrad. 1997. Violence and Daily Life: Reading, Art, and Polemics in the Citeaux Moralia in Job. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Runeburg, J. 1913. La bataille loouifer i édition critiçue d’après les mss. De l’arsenal et de boulogne. Acta Societatis Scientiarum Fennicas 37. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Rüther, Bjorn. 2022. Flail FAQ—What hits harder? Flail vs. Staff. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=f7a3jLx8ZJQ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Rüther, Bjorn. 2023. Flail FAQ—The Mangual! Weapon or Toy? Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ADxKtdxmxN4 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Sayers, William. 1983. Martial Feats in the Old Irish Ulster Cycle. The Canadian Journal of Irish Studies 9: 45–80. Available online: http://www.jstor.org/stable/25512561 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Scala, Gavino. 2021. La tradizione manoscritta del ”Livre du gouvernement des roys et des princes” di Henri de Gauchy. Studio filologico e saggio di edizione. Ph.D. thesis, University of Zurich, Zurich, Switzerland. [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, Alwin. 1889. Das höfische leben zur zeit der minnesinger. 1 vol. Leipzig: S. Hirzel. [Google Scholar]

- Seltman, Charles. 1946. The Ancient Coinage of Malta. The Numismatic Chronicle and Journal of The Royal Numismatic Society 6: 81–90. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/42663242 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Shartrand, Emily R. 2020. Sexual Warfare in The Margins of Two Late-Thirteenth-Century Franco-Flemish Arthurian Romance Manuscripts. Ph.D. thesis, University of Delaware, Delaware, DE, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Short, Ian. 2022. Historical Miscellany. Available online: http://www.anglo-norman-texts.net/media/2021/12/Short-Historical-Miscellany.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Shpakovsky, Viacheslav, and David Nicolle. 2013. Armies of the Volga Bulgars & Khanate of Kazan: 9th–16th centuries. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 33–34. [Google Scholar]

- Sitdikov, Airat G., Iskander L. Izmailov, and Ramil R. Khayrutdinov. 2015. Weapons, Fortification and Military Art of the Volga Bulgaria in the 10th—The First Third of the 13th Centuries. Journal of Sustainable Development 8: 167–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skhorokhod, Viacheslav, and Dariusz Blazhchek. 2020. Studies of Shestovytsia Barrows. Arheologia 2: 94–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skinner, Patricia. 2017. Living with Disfigurement in Early Medieval Europe. New York: Springer Nature, p. 84. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, John Alexander. 1876. Notes of Small Ornamented Stone Balls Found in Different Parts of Scotland, with Remarks on Their Supposed Age and Use. Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Scotland 11: 29–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Snook, George A. 1979. The Halberd and Other Polearms of the Late Medieval Period. American Society of Arms Collectors Bulletin 79: 3–13. [Google Scholar]

- Soler del Campo, Alvaro. 1985. La Evolucion del Armamento Medieval en el Reino Castellano-Leones y Al-Andalus (Siglos XII-XIV). Madrid: Collecion Adalid. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Spence, Lewis. 1917. Legends and Romances of Brittany. New York: Stokes. [Google Scholar]

- Spiro, Anna Lee. 2014. Reconsidering the Career of Nicholaus Artifex (active c.1122–c.1164) in the Context of Later Twelfth-Century North Italian Politics. Ph.D. thesis, Columbia University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Steele, Philip. 2002. Ancient Egypt. New York: Rosen Publishing, p. 12. [Google Scholar]

- Stengel, Edmund, and Fritz Menzel. 1906. Jean Bodels Saxenlied. Teil I. Unter Zugrundlegung der Turiner Handschrift von neuem herausgegeben von F. Menzel und E. Stengel. Marburg, Germany: Elwert’sche. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Sternberg, Aron. 1886. Die Angriffswaffen im Altfranzosischen Epos. 48 vols. Marburg: Elwert, p. 44. (In German) [Google Scholar]

- Stoljar, Samuel. 1985. Of socage and socmen. The Journal of Legal History 6: 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sturtevant, Paul B. 2016a. The Curious Case of the Weapon that Didn’t Exist. Available online: https://publicmedievalist.com/curious-case-weapon-didnt-exist/ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Sturtevant, Paul B. 2016b. Solving the Curious Case of the Weapon that Didn’t Exist. Available online: https://publicmedievalist.com/flail-redux/ (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Sturtevant, Paul B. 2017. The Medieval Weapon that Never Existed: The Military Flail. Medieval Warfare 6: 50–53. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48578200 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Svetec, Filip. 2023. Oružje na motki razvijenog i kasnog srednjeg vijeka u Hrvatskoj. Master’s thesis, Univeristy of Zadar, Zadar, Croatia. (In Croatian). [Google Scholar]

- Sweetenham, Carol. 2016. The Chanson des Chétifs and Chanson de Jérusalem Completing the Central Trilogy of the old French Crusade Cycle. Oxford: Routledge. [Google Scholar]

- Taavistainen, Jussi-Pekka. 2004. A Kisten from Mulli, Raisio—A Manifestation of Middle Europe in Southwestern Finland. Esti Arheoloogiaajakiri 8: 33–48. [Google Scholar]

- Talaga, Maciej, and Harrison Ridgeway. 2020. Historical Visuals and Reconstruction of Motion: A Gestalt Perspective on Medieval Fencing Iconography. Gestalt Theory 42: 145–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tardy, Jean-Mickael. 2020. La figure chevaleresque dans le jeu vidéo, de la sortie de la NES au Japon (1983) à aujourd’hui, une aventure transmédiatique. Master’s thesis, Université Jean Monnet, Saint-Etienne, France. (In French). [Google Scholar]

- Taylor, Edgar. 1837. Master Wace his Chronicle of the Norman Conquest from the Roman De Rou Translated With Notes and Illustrations. London: Pickering, p. 173. Available online: https://www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/41163/pg41163-images.html (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Terävä, Elina. 2014. Aseistettu arki Raaseporissa Aseet ja suojavarusteet linnalla ja sen ympäristössä. Master’s thesis, University of Helsinki, Helsinki, Finland. (In Finnish). [Google Scholar]

- The History Blog. 2016. Medieval copper scourge found at Rufford Abbey. Available online: http://www.thehistoryblog.com/archives/41442 (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Thibout, Marc. 1966. La légende de Roland dans l’art du Moyen Age. 2 vols. Bulletin Monumental 124: 334–38. [Google Scholar]

- Thompson, Jennifer A. 2000. Reading in The Painted Letter: Human Heads in Twelfth-Century English Initials. Ph.D. thesis, University of St. Andrews, St Andrews, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Thorbeck, Carlos Vara. 1999. El Lunes de las Navas. Jaen: University of Jaen. (In Spanish) [Google Scholar]

- Tihle, Peter. 2017. Udarno orožje v srednjem in novem veku. Master’s thesis, University of Ljubljana, Ljubljana, Slovenia. (In Slovenian). [Google Scholar]

- Toffee, John. 2013. Cacamwri, Osla Big-Knife and Llyn Lliwan. Available online: https://mabinogionastronomy.blogspot.com/2013/09/cacamwri-oslabig-knife-and-llyn-lliwan.html (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Tunis, Edwin. 1999. Weapons: A Pictorial History. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, pp. 35–36. [Google Scholar]

- Tuve, Rosemund. 1929. The Red Crosse Knight and Mediæval Demon Stories. PMLA 44: 706–14. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/457410 (accessed on 25 October 2023). [CrossRef]

- Tzouriadis, Iason-Eleftherios. 2017. The Typology and Use of Staff Weapons in Western Europe c. 1400—c. 1550. Ph.D. thesis, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Tzouriadis, Iason-Eleftherios, and Jacob Deacon. 2020. A Long-Distance Relationship: Staff Weapons as a Microcosm for the Study of Fight Books, c. 1400–1550. Acta Periodica Duellatorum 8: 45–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Utz, Richard. 2016. The Return to Medievalism and the Future of Medieval Studies. Proceedings of Anglistentag 2016 Hamburg. Edited by Ute Berns and Jolene Mathieson. Paper presented at Anglistentag 2016, Hamburg, Germany, September 21–24. [Google Scholar]

- van der Veen, Vincent. 2012. Crossbows and Christians. Medieval Warfare 2: 38–41. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/48577944 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Van Dyke, Eric, Caroline Mallary, Ryan Meador, and David Sansoucy. 2007. The Classic Suit of Armor An Interactive Qualifying Project Report. Bachelor’s thesis, Worcester Polytechnic Institute, Worcester, MA, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Veiga de Oliveira, Ermesto, Fernando Galhano, and Benjamin Pereira. 1983. Alfaia agrícola Portuguesa. Lisbon: Portugese National Institute of Science, Ethnology Study Centre. (In Portuguese) [Google Scholar]

- Veninger, Jacqueline. 2015. Archaeological Landscapes of Conflict in Twelfth-Century Gwynedd. Ph.D. thesis, University of Exeter, Exeter, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Vercelli Mappamundi. n.d. Available online: http://www.myoldmaps.com/early-medieval-monographs/2203-vercelli-mappamundi/225-matthew-paris-world/2203-vercelli2.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2023).

- Villemarqué, Théodore Hersart de la. 1846. Barzaz-Breiz: Cjamts Populaires de la Bretagne. 1 vol. Paris: Franck, pp. 199–202. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Vincent, Nicholas. 2015. The seals of King Henry II and his court. In Seals and their Context in the Middle Ages. Edited by Philipp R. Schofield. Oxford: Oxbow, p. 15. Available online: https://www.jstor.org/stable/j.ctvh1dsk8.6 (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Viollet-le-Duc, Emmanuel. 1874. Dictionnaire Raisonné de Mobilier Francais, Book 5. Paris: Morel, pp. 427–29. (In French) [Google Scholar]

- Waldman, John. 2005. Hafted Weapons in Medieval and Renaissance Europe: The Evolution of European Staff Weapons between 1200 and 1650. Lieden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Wamers, Egon. 1994. Die Fruhmittelalterlichen Lesefunde aus der Lohrstrasse (Baustelle Hilton II) in Mainz. Mainzer Archaeologische Schriften 20: 152–54. (In German). [Google Scholar]

- Warner, Philip. 1968. Sieges of the Middle Ages. Yorkshire: Pen and Sword, p. 37. [Google Scholar]

- Wasiak, Wojciech. 2012. Broń o artyście, artysta o broni w wirtualnej rzeczywistości malowideł średniowiecznych. Acta Universitatis Lodziensis. Folia Archaeological 29: 209–34. (In Polish). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterschoot, Werner. 2014. Felix De Vigne als boekillustrator. In Monte Artium 7: 115–34. (In Dutch). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whobrey, William. 2018. The Nibelungenlied: With The Klage. Indianapolis: Hacket, p. 43. [Google Scholar]

- Williams, Jennifer. 1979. Etzel der rîche—The depiction of Attila the Hun in the literature of medieval Germany: With reference to related Byzantine, Italic, Gallic, Scandinavian and Hungarian sources (450–1300). Ph.D. thesis, Queen’s University Belfast, Belfast, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, David M., and C. E. Blunt. 1961. The Trewhiddle Hoard. Archaeologia 98: 75–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zábojník, Jozef. 2009. K Problematike Bijakov Z Obdobia Avarského Kaganátu. Slovenska Archeologia 57: 169–82. (In Slovenian). [Google Scholar]

- Zdaniewicz, Radosław, and Marcin Adamiak. 2011. Relikt broni obuchowej z Chudowa. Acta Militaria Mediaevalia 7: 191–202. (In Polish). [Google Scholar]

- Zhirohov, Mikhail, and David Nicolle. 2019. The Khazars: A Judeo-Turkish Empire on the Steppes, 7th–11th Centuries. Oxford: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Zientara, Benedykt. 1970. Nationality Conflicts in the German-Slavic Borderland in the 13th-14th Centuries and their Social Scope. Acta Potoniae Historica 22: 207–25. Available online: https://rcin.org.pl/ihpan/dlibra/publication/19663/edition/5584#description (accessed on 25 October 2023).

- Zouache, Abbès. 2007. L’armement entre Orient et Occident au VIe/XIIe siècle: Casques, masses d’armes et armures. Annales Islamologique 41: 277–326. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Holdsworth, A.F. Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe. Histories 2024, 4, 144-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010009

Holdsworth AF. Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe. Histories. 2024; 4(1):144-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010009

Chicago/Turabian StyleHoldsworth, Alistair F. 2024. "Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe" Histories 4, no. 1: 144-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010009

APA StyleHoldsworth, A. F. (2024). Fantastic Flails and Where to Find Them: The Body of Evidence for the Existence of Flails in the Early and High Medieval Eras in Western, Central, and Southern Europe. Histories, 4(1), 144-203. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010009