Visualising the Modern Housewife: US Occupier Women and the Home in the Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945–1949

Abstract

:1. Introduction

Operation family, launched a few weeks before, has, as far as he could judge, been a failure—possibly the most disastrous mistake in Occupation policy.

2. The Modern Occupier Wife, the Home and Domestic Workers

This extended beyond the occupiers to victims of Nazism: Jewish women in Displaced Persons camps could be assigned or directly hired German domestics to work for them as a form of retribution (Grossmann 2009, pp. 208, 212). Not only was domestic work viewed by the occupier as appropriate for the defeated and occupied, but its absence was also considered a just reward for the victor women of the occupying forces, those housewives who had been “essential workers in the victory over fascism” (Giles 2004, p. 203). Different types of work thus aligned with the new occupation labour economy that, in turn, created new forms of ‘inferiority’.Once there was a commotion among our people, who had found that one of the scrubwomen in our headquarters had belonged to the Nazi organization for women in a very minor capacity. It seemed to me unnecessary to discharge her since I could think of no more fitting task to be performed by a former Nazi.

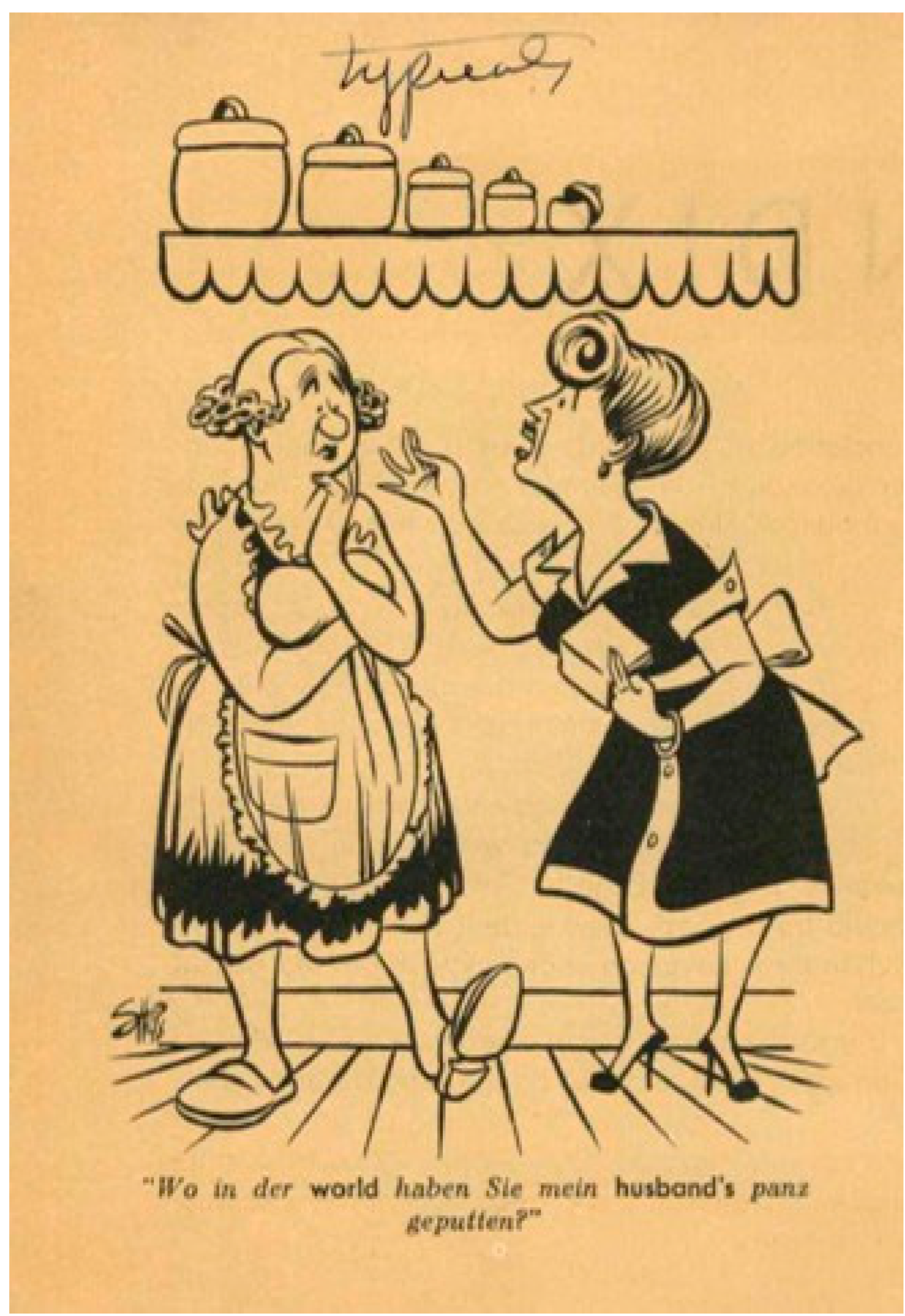

Women were thus a piece in the wider game of enacting occupation power through their position of mistress in the home. While women did not have access to the corridors of power, they did have “considerable authority over the German people”, especially those in her household (Easingwood 2009, p. 78). The wives were collectively presented, with encouragement and indeed instruction from occupation authorities, as a model to be seen, a tutor to be heard, and a generous provider of charity to be thankful for. But how did this play out in the intimate space of the home and, even more so, how were such interactions represented in occupation discourse, particularly in the visual archive?

3. Representations of the Modern US Occupier Wife and Occupier Home

3.1. Economic Modernity

But between the clothes of the Occupation women, conspicuous and with an air of elegance even if they came off the peg of some American department store, between their cuban-heeled and high-heeled shoes, their smart handbags, their colourful scarves, and their fur coats on the one hand, and the flat-heeled, worn shoes of the German women, their threadbare colourless overcoats, and their grey felt hats—that contrast was violent and provocative. The American women were groomed in a way that required much time and extensive cosmetic aids, and even if they wore their lipstick and rouge with moderation, they still looked like fashionable mannequins disporting themselves among the destitute and homeless.12

3.2. Domestic Modernity

Bread was a regular point of contention, a clash over which nation’s was better. Baking cakes was also a conduit through which to perform the perceived national superiority and modernity of the occupier, for the occupier woman to act as a tutor of domestic democracy:When very heavy bread continued from her kitchen despite the family’s protests, the American housewife took over. Morning after morning she descended bright-eyed to the kitchen where she made bread with available ingredients differently proportioned. Her daily experiments successfully convinced the cook who, in self-defense, began making good bread [emphasis added].

And in a similar example, “Although we were amazed at the German’s unfamiliarity with light cakes, most of us enjoyed mixing before an incredulous cook a beautiful light concoction destined to melt in the mouth. To see her taste the finished product was a real treat!” (AWBB 1949, p. 10). Victual mentoring was not always successful: one US wife wrote to her parents, “Well it is four o’clock and they [the children] want a cake for supper so guess I’d better go make it. Louisa [the cook] is pretty good at cooking the meals now and she has learned how to make cheese pies but she still can’t make a cake the children will eat. Guess I’m not a very good teacher”.17There are no egg custards in Germany, so German cooks and on-lookers in the kitchen, were completely dubious as to the thickening ability of the egg. When the thin soupy mixture, “No cornstarch? No flour?”—emerged from the oven perfect, the resultant expressions were well worth seeing!

3.3. Modern Gender and Family Relations

Suddenly there was a lull in the conversation. Betty had left Hunter’s last question unanswered. Instead she said, “You’ve nothing to tell me, Graham?”

“I don’t know what you mean”.

“I’m surprised at your bad taste, Graham. At your bad taste, if nothing else”.

“I really must ask you, Betty, to explain yourself”.

“You need to have established your mistress in our home. Or is that the local custom?”

The colonel leapt up. “Betty!” he said. He could not utter anything else.

The woman lit another cigarette. Her lips were trembling.

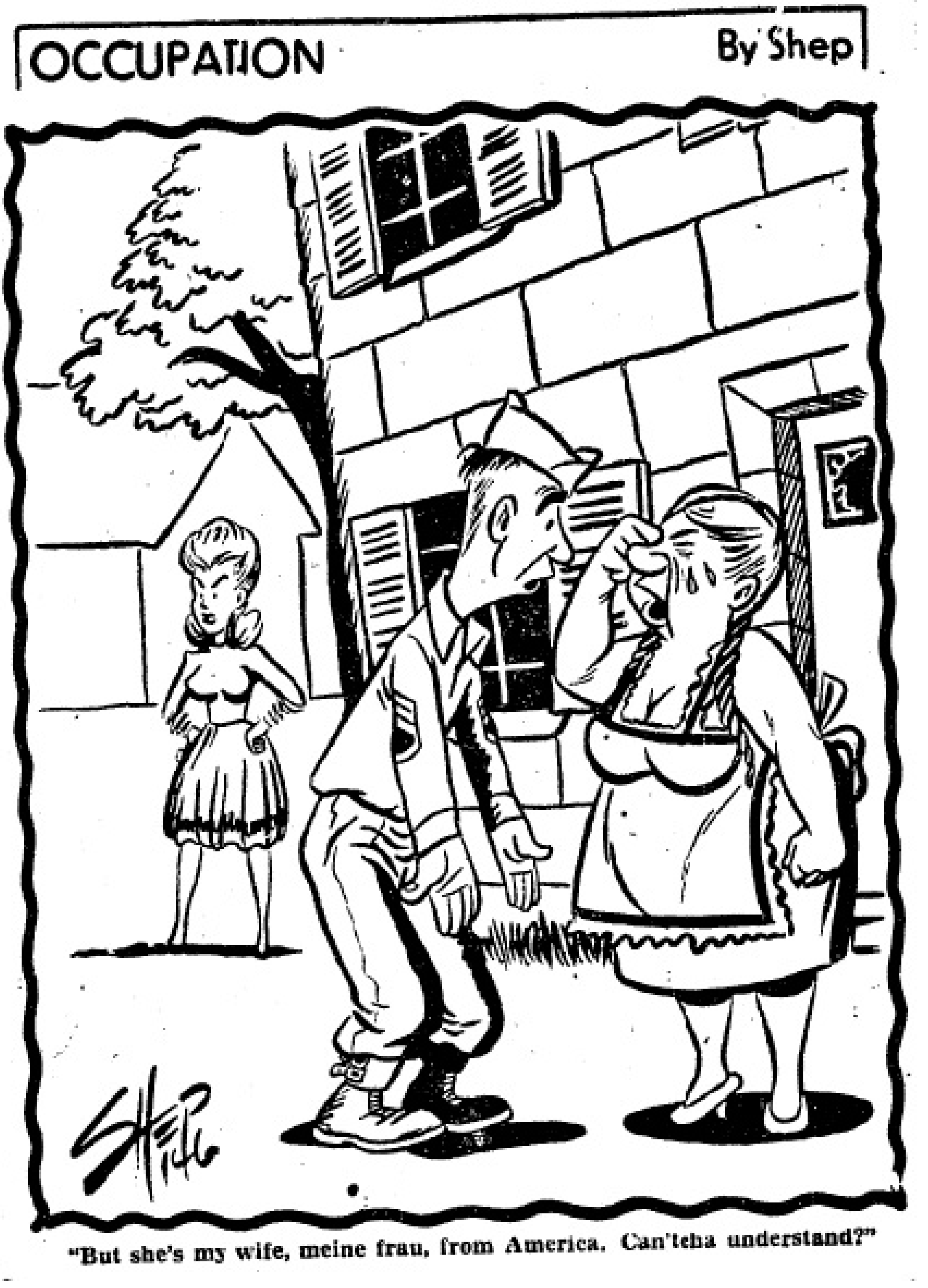

In tiresome familiarity, the perceived threat to occupier family life was often blamed on the domestic worker rather than the behaviour of the occupier man. Publications aimed at women or men often portrayed the German domestic worker in unflattering, comical and paradoxical ways—as an eager student of victor victuals or constant sexual threat. The contrast is captured again in the Sheppard example, with the occupied domestic worker cast as ‘unmodern’, available and pathetic, while the occupier wife mirrors contemporary Hollywood glamour, strength and individuality—even while being accused of depriving the US man of his pleasure.“It wouldn’t surprise me, Graham. There are sensational stories circulating back home about conditions out here. Having a mistress seems to be good form; after all, everybody knows that a German woman will sell herself for a packet of cigarettes”.

In an exchange of culinary nationalisms, Eva cooked familiar pork roast but also turkey for Thanksgiving (Höhn 2002, p. 78). She was particularly taken by the US-style BBQ and was pleased when the colonel and his wife bequeathed her their grill. Eva’s memories of working for a US couple are quite positive, and present a possible example of where the emulation of gender and family relationships in the home, within a 1940’s context, may have produced fruit, as well as breaking down wartime barriers. Yet, the desire to please one’s employer, as relayed through Eva’s memories, remains an expression of subservience to the occupier, reminding that even amicable relationships did not altogether remove the hierarchies of occupation power in the home, and neither did they provide much fodder for drawings or photographs in occupier publications during this period.First I planned everything: either a nice German meal or an American menu. Then the night before I discussed with the wife what I was going to cook. Then we had a nice soup, a first course, the main meal, dessert, wonderful fruit, in summer ice-cream, in winter pudding. Delicious. “Oh Eva”, [they would exclaim], “very much good! Very much”. I [also] made German pork roast, potatoes, many salads. Great soup.(Eva 2010)

4. Conclusions

In occupied Germany, gendered visualisations, in both caricature and staged photograph, were concise expressions of imagined occupier power that contained within them the supposed justifications for that power—as well as the promise of a changed future for the occupied.American superiority rested on the ideal of the suburban home, complete with modern appliances and distinct gender roles for family members. He proclaimed that the “model” home, with a male breadwinner and a full-time female homemaker, adorned with a wide array of consumer goods, represented the essence of American freedom.

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | |

| 2 | The broader historiography on occupied Germany is too large to do justice to here. Key examples on everyday encounters are Maria Höhn (2002) and Petra Goedde (2003). |

| 3 | |

| 4 | There were non-white occupier wives, particularly African American women in the US zone. This became more common over time. With the focus on the early part of the occupation and on visual narratives that privilege white occupier women, this article does not discuss the case of non-white occupier women. One author who does is Jaima (2016). Höhn and Klimke (2010, pp. 52, 189) also make reference to African American wives, but note that they did not arrive in large numbers until the 1950s, which is outside the scope of this paper. |

| 5 | Also, see this site for a visual example from Puck magazine. |

| 6 | |

| 7 | One outcome of the reform was that many domestic workers lost their jobs (Job Seekers Drawn to MG 1948). |

| 8 | |

| 9 | For more on the relationship between work/labour, power and war/occupation, please see de Matos (2015, pp. 65–87). |

| 10 | PX is a Post Exchange, a retail store on US bases. |

| 11 | This is an adaptation of the phrase “consumption and spectacle” from Giles (2004, pp. 104–5). |

| 12 | Interestingly, this is not unlike observations of “showy” Polish women made by German observers (compared to authentic tasteful German women). See Harvey (2003, pp. 122–23). |

| 13 | See Castillo (2005), So Wohnt Amerika (1949) and Giles (2004, p. 7). These exhibitions were also aimed against the Soviet Union in the cold war context. |

| 14 | Email correspondence, USARMY Wiesbaden, 2 March 2022. |

| 15 | Email correspondence, AWC Berlin, 19 November 2019. |

| 16 | In the US zone, at first the meal was paid from the German economy and after 1947 was provided by the employing family (IES 1947, Errata Sheet and p. 52). |

| 17 | Julia (Jewel) Kale to Mother & Dad, November 16, 1947. In Falzini (2004, p. 122). |

| 18 | See also Stars and Stripes issues for October 24, 25 & 26 and December 2, 16, 17, 22 & 29. |

| 19 |

References

- Adler, Karen H. 2012. Selling France to the French: The French Zone of Occupation in Western Germany, 1945–c.1955. Contemporary European History 21: 577–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvah, Donna. 2007. Unofficial Ambassadors: American Military Families Overseas and the Cold War, 1946–1965. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- American-German Women’s Club. 1947. Weekly Information Bulletin (Office of Military Government for Germany (US), Control Office), 100, July 1947. pp. 6, 12.

- Aresin, Jana. 2021. Locating Women’s Political Engagement: Democracy in Early Cold War US and Japanese Women’s Magazines, 1945–1955. Comparativ 31: 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, Caitriona. 2013. Housewives and Citizens: Domesticity and the Women’s Movement in England, 1928–1964. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Begiato, Joanne. 2023. A “Master-Mistress”: Revisiting the History of Eighteenth-Century Wives. Women’s History Review 32: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiscombe, Perry. 2001. Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-fraternization Movement in the US Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria. Journal of Social History 34: 611–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, Alison. 1999. Imperial Geographies of Home: British Domesticity in India, 1886–1925. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 24: 421–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British and German Women’s Activities. 1948. British Zone Review 2, June 26, pp. 18–19.

- British Army on the Rhine (BAOR). 1954. A Guide for Families in 2nd TAF [Tactical Air Force], 2nd ed. Bad Oeynhausen: BAOR. [Google Scholar]

- British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF). 1946. Know Japan. Kure: BCOF. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2019. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books Limited. First published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, Hilary. 2022. Introduction. In The Incorporated Wife. Edited by Hilary Callan and Shirley Ardener. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–26. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Marian Wade. 1947. GI Wife Is Outcast in Germany. The Sunday Star, March 16, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Susan L. 2016. The Good Occupation: American Soldiers and the Hazards of Peace. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, Greg. 2005. Domesticating the Cold War: Household Consumption as Propaganda in Marshall Plan Germany. Journal of Contemporary History 40: 261–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, Lucius D. 1950. Decision in Germany. Melbourne: William Heinemann Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Teju. 2019. When the Camera was a Weapon of Imperialism. (And When It Still Is). New York Times. February 6. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/magazine/when-the-camera-was-a-weapon-of-imperialism-and-when-it-still-is.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Cowling, Daniel. 2018. “Gosh … I think I’m in a dream!”: Subjective Experiences and Daily Life in the British Zone. In Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany. Edited by Camilo Erlichman and Christopher Knowles. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 211–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Eugene. 1999. The Death and Life of Germany: An Account of the American Occupation. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- de Grazia, Victoria. 2005. Irresistable Empire: America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe. Cambridge: The Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Matos, Christine. 2015. Labor under Miltary Occupation: Allied POWs and the Allied Occupation of Japan. In Japan as the Occupier and the Occupied. Edited by Christine de Matos and Mark E. Caprio. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2007. “All One Could Desire”: British Women Remember Life in Post War Germany. UCLA Thinking Gender Papers. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/41k766w0 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2009. British Women in Occupied Germany: Lived Experiences in the British Zone, 1945–1949. Ph.D. dissertation, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2011. British Women at Work in the British Zone of Occupied Germany, 1945–1949. Women’s History Network. November 6. Available online: https://womenshistorynetwork.org/british-women-at-work-in-the-british-zone-of-occupied-germany-1945-49/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Erlichman, Camilo, and Christopher Knowles, eds. 2018. Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany: Politics, Everyday Life and Social Interactions, 1945–1955. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Eva. 2010. Interview with Author, 7 June, Spandau. Interpreter: Robert Dambon. Translator/Transcriber: Francesca Beddie. [Google Scholar]

- Falzini, Mark W., ed. 2004. Letters Home: The Story of an American Military Family in Occupied Germany 1946–1949. Lincoln: iUniverse. [Google Scholar]

- Feigel, Lara. 2016. The Bitter Taste of Victory: Life, Love and Art in the Ruins of the Reich. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Joseph. 1948. Dependent from Leningrad. European Stars and Stripes, February 21, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- France-UK-US Occupation Statute. 1949. France-United Kingdom-United States Occupation Statute for Germany. The American Journal of International Law 43: 172–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, Oliver J. 1953. The American Military Occupation of Germany 1945–1953; Karlsruhe: Historical Division, Headquarters, United States Army Europe.

- Gerster, Robin. 2015. Capturing Japan: Australian Photography of the Postwar Military Occupation. History of Photography 39: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Judy. 2004. The Parlour and the Suburb: Domestic Identities, Class, Femininity and Modernity. Oxford and New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner, Ann-Kristin. 2018. Shared Spaces: Social Encounters between French and Germans in Occupied Freiburg, 1945–1955. In Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany. Edited by Camilo Erlichman and Christopher Knowles. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Goedde, Petra. 1999. From Villains to Victims: Fraternization and the Feminization of Germany, 1945–1947. Diplomatic History 22: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedde, Petra. 2003. GIs and Germans: Culture, Gender, and Foreign Relations 1945–1949. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Roger. 2007. Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, Atina. 2009. Jews, Germans and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gulgowski, Paul W. 1983. The American Military Government of United States Occupied Zones of Post World War II Germany in Relation to Policies Expressed by Its Civilian Governmental Authorities at Home, during the Course of 1944/45 through 1949. Frankfurt: Haag & Herchen Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- H.D. 1946. The Psychology of Nazism. British Zone Review 1, September 28, pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Habe, Hans. 1956. Off Limits: A Novel of Occupied Germany. London: George. C. Harrup and Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Elizabeth. 2003. Women and the Nazi East: Agents and Witnesses of Germanization. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hiring Germans Brings Problems. 1948. Hiring Germans Brings Problems. Stars and Stripes (Europe), August 6, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, Maria. 2002. GIs and Fräuleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, Maria, and Martin Klimke. 2010. A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 52, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Information and Education Service (IES). 1947. An Introduction to Germany for Occupation Families. Frankfurt: HQ United States Forces European Theater. [Google Scholar]

- Instructions to Manager. 1945. Berlin Main Labour Office, 12 October, B036 4/31-3/70, Allied Kommandatura Berlin, Ländesarchiv Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Jaima, Felicitas R. 2016. Adopting Diaspora: African American Military Women in Cold War West Germany. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Job Seekers Drawn to MG. 1948. Job Seekers Drawn to MG by New Mark. The Stars and Stripes, June 27, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspin, Deborah D. 2002. Conclusion: Signifying Power in Africa. In Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Edited by Paul S. Landau and Deborah D. Kaspin. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 320–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Howard. 1948. Mrs Ybarbo Admits She Shot Her Husband. Stars and Stripes (Europe), December 21, pp. 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, Christina M. 2015. The Comic Art of War: A Critical Study of Military Cartoons, 1805–2014. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, Lee. 2017. Logistics Matters and the US Army in Occupied Germany, 1945–1949. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, Linda L. 2014. Logistic Matters: The Growth of Little Americas in Occupied Germany. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Landau, Paul S. 2002. Introduction: An Amazing Distance: Pictures and People in Africa. In Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Edited by Paul S. Landau and Deborah D. Kaspin. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Laws of War. 1899. Laws of War: Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague II); 29 July 1899. ©2008. The Avalon Project. Available online: http://avalon.law.yale.edu/19th_century/hague02.asp (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Life in Germany. 1947. Life in Germany: A Taunton Wife Settles In: Colony with Own Women’s Institute. Somerset County Herald, January 4, p. 6. [Google Scholar]

- Macmillan, Mona. 2022. Camp Followers: A Note on Wives of the Armed Services. In The Incorporated Wife. Edited by Hilary Callan and Shirley Ardener. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 89–105. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Matsuda, Hiroko. 2012. America, Modernity and Democratization of Everyday Life: Japanese Women’s Magazines during the Occupation Period. Inter-Asia Cultural Studies 13: 518–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, Verity G. 2014. Indirect Agents of Empire: Army Officers’ Wives in British India and the American West, 1830–1875. Pacific Historical Review 83: 378–409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meehan, Patricia. 2001. A Strange Enemy People: Germans under the British, 1945–1950. London: Peter Owen Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Mill, John Stuart. 1869. The Subjection of Women. Available online: https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/mill-john-stuart/1869/subjection-women/ch01.htm (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- My First Week in Germany: By a BAOR Wife. 1946. The Evening Telegraph, September 6, p. 2.

- Nichols, Bradley J. 2015. Housemaids, Renegades and Race Experts: The Nazi Re-Germanisation Procedure for Polish Domestic Servant Girls. German History 33: 214–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, Shane. 2023. Irish maids in New York Were Subject to a Racist Slur in the 19th Century. Irish Central. October 2. Available online: https://www.irishcentral.com/roots/history/irish-maids-new-york-racist-slur (accessed on 1 October 2023).

- Oliver, Emily. 2018. “Heaven Help the Yankees if they Capture You”: Women Reading Gone with the Wind in Occupied Germany. German Life and Letters 71: 193–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Operation Vittles: An American Cook Book. 1949. Weekly Information Bulletin (Office of Military Government for Germany (US), Control Office) 155, February. p. 9.

- Piehler, H. A. 1948. The British Family in Germany. British Zone Review 2, October 15, pp. 6, 18. [Google Scholar]

- Pumphrey, Martin. 1987. The Flapper, the Housewife and the Making of Modernity. Cultural Studies 1: 179–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reagin, Nancy R. 2007. Sweeping the German Nation: Domesticity and National Identity in Germany 1870–1945. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Red Letter Day. 1946. Red Letter Day: Nottingham Wife in BAOR. Party: Thrill of Going to Germany; Meeting Husband After Many Years. Nottingham Evening Post, August 27, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Reed, Ernie. 1949. MG Hears Charge GI’s Wife Assaulted German “Girlfriend”. Stars and Stripes (Europe), March 6, p. 3. [Google Scholar]

- Reinisch, Jessica. 2013. The Perils of Peace: The Public Health Crisis in Occupied Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Sheppard, Don (Shep). 1946. Occupation. Southern Germany Stars and Stripes, April 22, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Shot Fraulein in Rage. 1949. Shot Fraulein in Rage, Sergeant Admits at CM. Stars and Stripes (Pacific), June 22, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Soldiers: Some of Them “Never Had It So Good”. 1947. Soldiers: Some of Them “Never Had It So Good”. Life. February 10 p. 89. Available online: https://books.google.com.au/books?id=HEoEAAAAMBAJ&pg=PA88&source=gbs_toc_r&cad=2#v=onepage&q&f=false (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Soper, Kerry. 2005. From Swarthy Ape to Sympathetic Everyman and Subversive Trickster: The Development of Irish Caricature in American Comic Strips between 1890 and 1920. Journal of American Studies 39: 257–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Southall, Sara, and Pauline M. Newman. 1949. Women in German Industry; Visiting Expert Series No. 14. Frankfurt: Office of the Military Government for Germany (US).

- So Wohnt Amerika [sic]. 1949. Information Bulletin (Office of Military Government for Germany (US), Control Office), December. pp. 63–67.

- Style-Hungry. 1947. Style-Hungry. The Wilmington Morning Star, September 19, p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- The American Women of Blockaded Berlin (AWBB). 1949. Operation Vittles Cookbook. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag. Available online: https://archive.org/details/operationvittles00berl/mode/2up (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- Thomas, Julia Adeney. 2008. Power Made Visible: Photography and Postwar Japan’s Elusive Reality. Journal of Asian Studies 67: 365–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Traue, Boris, Mathias Blanc, and Carolina Cambre. 2019. Visibilities and Visual Discourses: Rethinking the Social with the Image. Qualitative Inquiry 25: 327–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Triangle Drove Yank to Shoot Her. 1949. Triangle Drove Yank to Shoot Her, Maid Says. Stars and Stripes (Europe), June 19, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler May, Elaine. 1988. Homeward Bound: American Families in the Cold War Era. New York: Basic Books, Inc. Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Tyler May, Elaine. 1998. Pushing the Limits: American Women 1940–1961. New York: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Ullman, Frederic, Jr. 1947. prod. This Is America: Germany Today. New York: RKO Pathe Inc. Available online: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kjSBZLSpD8Q (accessed on 28 December 2023).

- US Army, Army Information Branch. 1944. Pocket Guide to Germany; Washington, DC: US Government.

- US Forces European Theater. 1947. An Introduction to Germany for Occupation Families; Frankfurt: Information and Education Service.

- Weinreb, Alice. 2017. Modern Hungers: Food and Power in Twentieth-Century Germany. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Welskopp, Thomas, and Alan Lessoff. 2012. Fractured Modernity—Fractured Experiences—Fractured Histories: An Introduction. In Fractured Modernity: America Confronts Modern Times, 1890s to 1940s. Edited by Thomas Welskopp and Alan Lessoff. Berlin: Walter de Gruyter GmbH, pp. 1–17. [Google Scholar]

- Wife’s Return to EC Sought. 1949. Wife’s Return to EC Sought in Assault Case. Stars and Stripes (Europe), May 14, p. 4. [Google Scholar]

- Wildenthal, Lora. 2001. German Women for Empire, 1884–1945. Durham and London: Duke University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Willoughby, John. 1998. The Sexual Behavior of American GIs during the Early Years of the Occupation of Germany. The Journal of Military History 62: 155–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, Mark R. 2016. Creative Destruction: American Business and the Winning of World War II. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wood, Alice. 2020. Modernism and Modernity in British Women’s Magazines. Milton: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Ziemke, Earl F. 2003. The US Army in the Occupation of Germany; Washington, DC: Center of Military History United States Army, First published 1975. Available online: https://history.army.mil/html/books/030/30-6/cmhPub_30-6.pdf (accessed on 24 December 2023).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2024 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

de Matos, C. Visualising the Modern Housewife: US Occupier Women and the Home in the Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945–1949. Histories 2024, 4, 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010001

de Matos C. Visualising the Modern Housewife: US Occupier Women and the Home in the Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945–1949. Histories. 2024; 4(1):1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010001

Chicago/Turabian Stylede Matos, Christine. 2024. "Visualising the Modern Housewife: US Occupier Women and the Home in the Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945–1949" Histories 4, no. 1: 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010001

APA Stylede Matos, C. (2024). Visualising the Modern Housewife: US Occupier Women and the Home in the Allied Occupation of Germany, 1945–1949. Histories, 4(1), 1-23. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories4010001