Abstract

Thousands of Allied women arrived in occupied Germany after the Second World War as the wives of military and civilian men working in the occupation apparatus. Yet rarely have these women been seen as active agents of occupier power and knowledge. One way of understanding their role, or how it was imagined, is through images and textual representations. With a focus on the early years of occupation (1945–1949) and visual representations of US wives, this article examines the occupation household that was serviced by occupied domestic workers, in turn drawing comparisons to imperial contexts. Visual cues in selected photographs and caricatures suggest a presumed superior occupier modernity that was both performative and educative, mediated by a class-like asymmetrical relationship. These representations have been divided into three key themes: economic modernity, as through consumerism; domestic modernity in the home; and modern gender and family relations. Here, occupier women’s bodies were contrasted against the occupied to signify the power, prestige and modernity of her nation as an occupying power, in turn revealing both the shape of everyday power relations in the home and the paradoxical aims of the occupation itself.

1. Introduction

Operation family, launched a few weeks before, has, as far as he could judge, been a failure—possibly the most disastrous mistake in Occupation policy.()1

Occupation studies has yet to thoroughly analyse the role of women as occupiers, especially married women who participated in the mid-20th century occupations after the Second World War. Between 1946 and 1949, thousands of Allied wives arrived in occupied Germany, children often in tow, to join husbands working in the military and civilian occupation apparatus. Part of ‘Operation family’, as referred to in the epigraph, the women, when acknowledged at all, have often been dismissed as anything from an extravagant appendage to a disruptive intrusion into serious masculine occupation business. Echoing Hans Habe’s fictional character, US Colonel T. Hunter, from his occupation novel Off Limits quoted in the epigraph above, one contemporary US newspaper article posed, “Is the American wife in Germany an angel in slacks and bandanna, or is she an official mistake?” () Was she, dressed in the garb of the modern era, contributing, without title or pay, to the work of occupation, or interrupting it? Rarely has the occupier wife in Germany been examined as an active agent of occupation knowledge and power, as wife, mother, citizen, victor, supervisor, teacher and diplomat. With attention to textual and visual representations, this article examines the US woman and the vital space in which she enacted her agency as an occupier, the home serviced by occupied domestic workers. It particularly considers contemporary publications that visually contrasted the occupier wife with the occupied (mostly German) women working in her household to emphasise the former’s status as a modern woman. In creating this contrast, technologies associated with victory in war, which facilitated perceptions of national superiority, were implicitly linked to the housewife and modern home, even while the latter, in the occupation context, also exuded symptoms of domestic imperialism.

This article can be seen as a response to ’s () call to show the activities and bodies of married women as “central to explanations of how provincial, metropolitan, colonial, and global societies functioned”, and this can include military occupation. While Begiato focusses on Britain and the 18th century, their words have wider geographical and temporal relevance. If only the limitations placed on married women receive attention, then “their significance as agents and actors in broader social, cultural, economic, and political forces is marginalised or exceptionalised” (). One aim of this article is to make occupier wives and their roles in the occupation apparatus more visible through a focus on the US zone, though it must be acknowledged that there were also participant wives from Britain, France and the Soviet Union. Occupation historiography tends to privilege the military and political, usually within a cold war paradigm, while eliding the occupation home. Yet women have a long history as participants in military, colonising, and occupying projects. In recent decades, occupation historiography has begun to shift as it moves to examine the ‘everyday’ occupation and more diverse encounters between occupier and occupied. Emblematic of this development is Camilo Erlichman and Christopher Knowles’ (() Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany). Within this turn, such encounters remain dominated by relations between Allied occupier men and German occupied women,2 though greater inclusion of the woman occupier is also evident. For instance, single women travelled to Germany to work for the occupation forces in the civilian sector, and their individual “lived experiences” in the British zone are the focus of ’s thesis (another example is ). Other women came as advisors on women’s matters, like industry engagement and labour rights (for example, ). Yet documenting occupier wives, whose job was in the home rather than the office or public sphere, remains the most neglected or incomplete task. While many general occupation histories make passing references to wives and families, (), who was part of the British occupation in Hamburg, was one of the first to give sustained attention to those in the British zone. Less is written of the French and Soviet zones.3 There have been several publications on US military families abroad, including ’s () meticulously researched Unofficial Ambassadors and in a chapter of ’ () (The Good Occupation). Military wives more generally are included in the definition of the ‘incorporated wife’, those women whose ascribed “social character” is an “intimate function of her husband’s occupational identity and culture” (). () has described military wives as excluded “from the central purposes of their husbands” as they are “[m]arked by their womanhood” as unsuitable for military purposes. Yet this is not necessarily so for occupier wives as those very essentialised “markers” were deemed suitable for both the performance of prestige and the building of peace. While much of the above literature begins to capture the personal experiences of occupier wives, seldom has attention been given to the official expectations of her role and the place of a home serviced by domestic workers in the wider occupation power dynamic.

This article assumes not just the presence of occupier wives, but that they were active participants in the occupation power hierarchy, especially in the space of the home.4 Comparisons to the colonial household can be helpful in illuminating this, and what () calls “imperial domesticity” provides a useful lens through which to view the occupier wife. “In making the imperial home central”, states (), “it becomes apparent that the mistress/servant relationship both blueprinted and reinforced the larger ideologies of the empire”. While an occupation, like colonialism, largely depends on military might or the threat of violence, over the longer term it requires legitimisation through non-military everyday practices, and it is here the home as a space of occupation becomes important. Under colonialism, women’s “domestic roles reproduced imperial power relations on a household scale and the political significance of imperial domesticity extended beyond the boundaries of the home”, and this article contends this also applies to occupation domesticity (). Relations of occupation power do not politely stop at the front door of the occupier’s transient home (). Just as for colonial women, the “management and surveillance of servants within rigidly hierarchical households articulated and reinforced class distinctions” that reified the asymmetrical relations of occupation power (). That is, it was via relationships with her husband and the (mostly) women domestic workers assigned to or employed in the home that the occupier woman reproduced “the social, moral and domestic values legitimating” the rule of the occupying nations (). As () reminds, “power is always expressed both through bodies and on bodies”.

The second aim of this article is to reveal the occupier wife as a missionary of modernity, to showcase both herself and her home to the occupied as symbols of the modern US family and of democracy, consumerism and capitalism. The most precise way of demonstrating this is through visual sources, historical traces that capture the implicit knowledge regime underpinning the daily practice of occupation. The Second World War can be cast as a clash of modernities, with victor powers wont to present themselves as an archetype of modernity, while claiming an incomplete or deformed process of modernisation for the defeated. As scholars like () have articulated, responses to the late 19th century moral crisis of modernity or fin de siècle, later intensified by the carnage of the Great War, led to movements that articulated alternative modernities, of which 20th century fascism and Nazism, along with communism, were the most obvious. Fascism, Griffin argues, “sought to realize a new synthesis between tradition and modernity” as a solution to this perceived moral crisis in order to create a new future; that is, to look backwards as well as forwards (). Nazi discourse in the East, for instance, cast German culture as modern and Polish as ‘backwards’. As () puts it, to be German was to be “both ‘modern’ and Nazi”. This demonstrates the elastic and self-serving goals of such assertions and their discursive relationship to the enactment of power: the ‘modern’ coloniser can suddenly become the ‘unmodern’ occupied.

This clash of perceived modernities thus played out in occupation relations and victor attitudes and policies, importantly including those related to women. Here, modernity can be interpreted in its more cultural and social settings. In the occupied Japan context, modernisation did not just apply to reform of “political or economic structures but of traditions, beliefs, and the social relations they produce” (). In Germany, the latter was also a target of reform. Both Germany and Japan were subjected to Allied pseudo-psychological analyses during the war and postwar that pointed towards deformed masculinities, hence to deformed family structures, which in turn deformed that creation of modernity, the nation-state (; ; ). But Germany was a western nation, and while the victor powers could not brand, say, German technology or science as ‘backward’, they could focus on Nazi social relations as failing to stand up to their definitions of modernity, including the family. This was not necessarily new and shares similarities with John Stuart Mill’s claim that the “surest test and most correct measure” of civilisation was its “elevation or debasement” of the “social position of women” (). “[R]esponses to ‘the modern’”, says (), “are to be found not only in narratives of the public city but also in stories of … the home, consumer relations, married sexuality, domestic service”. Women, especially as wives and mothers, were thus vital to this narrative, and the occupiers framed occupied women as requiring liberation from extreme Nazi patriarchy, or else presented them as trapped by tradition in contrast to the ‘modern’ Allied woman. As () phrases it, “[t]he modern American Housewife is not bound to the past or tradition; she is neither fussy nor old-fashioned. She is efficient, up to date, knowledgeable about domestic technology and an expert consumer”. In this way, occupier self-perceptions that victory in war ‘proved’ its version of mid-twentieth century modernity, linked to consumerism and democracy, particularly that of the United States and inclusive of claims to a moral superiority “synonymous with the direction of civilization itself”, was a model to be emulated (). While US psychological analyses of the ‘German mind’ at first shared similarities with other Allied diagnoses, the United States, as clearly explained by (), came to prioritise this need to spread “American, or ‘Western’, values and ideas about democracy” as the antidote. This sense of US modernity and mission was not only enacted by occupier wives in the home, but visually articulated through the (imagined) bodies of both occupier and occupied women.

Visual sources, therefore, play an important role in the article to reveal the role of occupier wives, their homes and their families as displays of US modernity, of making “power visible” (). In an article written for the New York Times in 2019, Teju Cole articulated the capacity of images to be “part of the language of visual domination” (). The camera could act as “a weapon of imperialism”, and photography as “a vital aspect of European colonialism”. Anthropological images juxtaposed the colonised as living in the past, bound and constrained by tradition, against the coloniser sitting in pith helmet and white pants, representing the modern, the progressive, the future. These contrasts between crude interpretations of modernity and tradition, whether in image or text, served as a shared language to justify the civilising mission and imperial power of the colonising nation. As stated by (), there is a “growing critique of photography as both a tool of imperialism and a neocolonial medium of framing places and peoples”, and this can be extended to other types of visual narratives, such as drawings and paintings, as well as to further asymmetrical contexts like military occupation. These images are created by the occupier (or coloniser), and as such should not be read as a documenting of the ‘Other’, but of the self: “[w]hat they do document very well … is a cultural encounter, and the responses to that encounter by members of one culture in particular” (). The images used in this article are of course not of a white westerner and a non-western ‘Other’, but two white nations, one victor and one defeated. However, there are precedents here too, particularly in the world of caricature and its depictions of US or British and Irish women. The Irish maid in the US household was often stereotyped as “sub-human, toothless, and brutish”, in contrast to the US or British mistress, and similar stereotyping tools were employed against German women working in US occupier homes ().5 As stated by (), “these caricatures were sometimes deployed as weapons of social control, used to justify the active abuse of passive neglect of minorities”, or in this case justifying the place of the defeated and occupied in the occupation hierarchy. Images of German women used in this article may thus be placed within this longer history of caricature and racial stereotyping, along with imperial tools of visual domination.

This article, thus, pays attention to visual and other representations of occupier wives, modernity and power in the home, in particular those that compare German with Allied women. As this is most obvious in US publications, the article focusses on the US zone while acknowledging that the experiences of Allied women extended to other zones, and to other occupied areas such as Japan. Through women, US power could be cast as progressive, and the visual evidence conveys economic and social markers that clearly contrast the occupier’s self-perceived modernity against the less-modern occupied. This article utilises sources more likely to have women as readers, contributors, or as topics of discussion, including newspaper articles, a recipe book and occupation fiction. The visual sources are from contemporary publications with large readerships, such as Life magazine and Stars and Stripes, and from guides provided to families in occupied Germany. It is important to note that most of these publications were not aimed at the occupied but rather the occupier nations, thus acting to reinforce and reproduce self-perceptions of superiority and modernity and provide justifications for the occupation to a home audience. A close reading of textual and visual cues was conducted, both in individual primary sources and collectively as a shared visual and textual currency of US occupation thought.

Occupied homes, then, alongside the more masculine corridors of the Kommandatura building in Berlin or the streets frequented by the Allied soldier in Frankfurt or Munich, were also sites of occupation power. With the above aims in mind, section two of this article will focus on the background of and the broader expectations for occupier wives, the home and domestic workers. The third section will concentrate on interactions in the occupier’s household, and on visual and other representations of the US occupier wife in the domestic space, especially in relation to the three themes of economic modernity, domestic modernity and modern gender relations. Through this approach, it is hoped a more nuanced understanding of the roles of the US woman in Germany, and her relationship to victor power and modernity, can be revealed, along with the value of the visual record in enabling that understanding to emerge.

2. The Modern Occupier Wife, the Home and Domestic Workers

Known as the ‘dependents’, wives and children of all ranks of US occupying forces arrived in Germany from 1946. Families began landing in April, and by mid-1947, over 5000 US women lived there (; ).6 At the end of 1949, there were 17,621 military families in the US zone, comprising over 30,000 family members (; ). The wives in all zones were partners to their spouses in the occupation mission, or, as () puts it, “‘team members’ in addition to their traditional supportive role”. The women’s first job in Germany was to provide a familiar home for their husband to enable him to complete his mission, to bring ‘normal’ family life to the occupation man. This would not only create greater stability, increase the likelihood of term completions, and ensure future recruitment, so the arguments went, but “would be convincing evidence that we were in Germany for the long stay” (). Considering the well-known stories of sexual relations with German women and high rates of sexually transmitted diseases, the women were also there, in that long stereotypical role of the middle-class housewife, to improve morals along with morale. They can also be viewed as a global extension of the postwar transition of women from work back to the home, the rise of a “new ‘domesticity’” encouraging women to embrace supposed feminine tasks (). Creating an expatriate homelife offered, within the structure of the patriarchal nuclear family, an alleged antidote to chaos and change not just in defeated Germany, but also to the war’s broader challenges to entrenched gender roles (; ). The occupation wife would nurture her husband, children, and a new Germany.

After making the decision to bring occupation families to Germany, the requisitioning of buildings to make homes for them proceeded apace (). Undamaged furnished hotels and homes of the occupied, including houses and apartments, were targeted, and it made little difference whether the owner was a “Nazi or employee of military government” (). These homes were often taken directly from an already devastated and struggling occupied population. Furniture and other material objects could also be requisitioned, known collectively as chattels (). This was a cheap process of providing homes for the occupiers as the expenses were charged to the occupation, paid for by the German taxpayer (). The taking of housing immediately enacted the asymmetrical power balance, turning German homes into Allied outposts. In the US zone, the divisions between occupier and occupied were often visibly noticeable, especially the ‘Little Americas’, guarded, isolated and self-sufficient occupier communities fenced off by barbed wire. Once a property was no longer required, it was returned, along with internal effects, to the original German owners, known as derequisitioning.

Many occupier women in all zones embraced the role of supportive partner in their new homes. For some, because of the war, it was their first chance to make a home with their husbands, or a reunion after many years apart (; ). Others questioned what else they could do to contribute towards the occupation. While it was possible for some wives to find formal employment with civilian authorities, as one US newspaper pointed out, “the average wife is barred from making any constructive contribution to the life of the community where her husband works. She may not take a government job unless she signs for a year, and most wives are uncertain about how long their husbands will be here” (). Instead, occupier women found other methods to contribute, such as gathering into women’s institutes and wives’ clubs. Many of the women’s groups and clubs invited German women to lectures and discussions, conducted charity drives and collected clothes or shoes for German children and orphanages (especially at Christmas), and ran other events, such as a German–US recipe competition. They volunteered for the Red Cross, the Salvation Army, the German Youth Movement and the Society of Friends. During the Berlin Airlift, the American Women’s Club published a collection of recipes to raise money for charity (; ; ; ; ). This is just a small sample of the typical middle-class-style charity work many wives of occupier men undertook in Germany to “promote good feeling” ().

But it is the occupier household and the relations within that space that are of most concern here. While requisitioning of homes decreased over time, with reduced numbers of personnel and the building of new accommodations and facilities, it continued well into the 1950s (). The created compounds provided leisured and comfortable lives for occupation families, and were the stage on which to showcase the supposed domestic superiority of the victor-occupier. While these spaces were tightly policed in terms of who could enter and who was prohibited, Germans were often invited in. This was because the homes for the occupiers required a new kind of army made up of firemen, gardeners, and domestic workers—the latter to cook, to clean and to care for the children of the occupiers.

Domestic workers were often supplied free of charge to the occupier family, at least in the early years. Along with requisitioning, the use of domestic servants in this way was justified by a perhaps creative interpretation of the 1899/1907 “Convention with Respect to the Laws and Customs of War on Land (Hague, II)”, of which Article 48 states that occupied territory “will in consequence be bound to defray the expenses of the administration of the occupied territory on the same scale as that by which the legitimate Government was bound” (). In 1949, with the creation of West Germany and the resumption of a German federal government, the Occupation Statute protected these rights of the occupier (). Both requisitioned accommodation and the provision of domestic workers for the occupiers were implicitly part of, it appears, the occupiers’ terms of defeat and punishment.

In US-occupied Germany, “40,000 domestic employees were provided free of charge”, and continued on a decreasing scale into the 1950s (). A 1947 This is America newsreel proclaimed there was “no servant problem” in occupied Germany and that a “typical [US] housewife may have a housemaid, a nursemaid for the children, and a gardener, all German” (). At first, the assignment of domestic workers depended on the husband’s rank, but after 1947, only the first domestic worker was free, with further help hired at low cost to the occupier—for example, USD 20 a month for a full-time cook (; ). After the 1948 currency reform, US occupiers engaged domestic services directly at German rates of pay rather than going through the US Civilian Personnel Branch ().7 Despite some changes related to costs and hiring procedures, and the impacts of currency reform, the practice of having a domestic worker remained remarkably consistent over time.

These German domestic workers were not always from the working class. While there had always been domestic workers in Germany, there was a shift in who made up those numbers. As some positions opened in the postwar industrial sector for women, many working-class women moved from more ‘traditional’ jobs, including domestic work, into that sphere, and were also more likely to be involved in sex work. With many women left as the heads of families, middle- and upper-class women also needed to provide their families with economic support. Aside from white collar office jobs, domestic work in occupier homes was one of the more desired sources of work as it promised shelter, warmth and food. As () points out, “used coffee grounds and tea leaves” and other types of leftovers could be collected and reused. At a time when the calorie intake was somewhere between 1000 and 1200 calories a day and there was an extreme housing shortage, the attraction of these factors cannot be underestimated ().

Domestic work also made sense given the cultural, political and even military emphasis on domestic skills for, especially, middle-class German women in the pre and wartime eras. The German woman was idealised from the time of unification in the late 19th century, reaching a nationalist zenith during the Nazi era. The ‘Kinder, Küche, Kirche’, or ‘Children, Kitchen, Church’, slogan that summarised women’s expected national maternal and moral roles from that era is well known, but the foundations of German housekeeping have deeper roots. Bismarck is credited with saying that “[i]n the domestic tradition of the German wife and mother, I see a more secure guarantee of our political future than in any of our fortresses” (). Young Polish women of ostensible German blood were ‘re-Germanised’ by the Nazis through employment as domestic workers in Germany, with the German woman as both supervisor and tutor.8 Thus, long before the Second World War, long before the defeat of Germany by the Allied nations, the home had been appropriated to support both discourses of nationalism and military needs. To become, then, a domestic worker in the occupied home was a logical choice given women’s skills in this domain, even if it now meant that, for many, there were not one but two homes to clean, double the meals to prepare, and two families of children to care for—and they were used to reinforce the prestige of the occupier rather than their own nation.

Work that involved physical labour could also be viewed as just punishment by the Allies, especially for those who had been Nazis, and domestic work was often seen in this category. The Allied Kommandatura instructed the Berlin Main Labour Office in 1945 that Germans who were “more than a nominal Nazi” could not be employed by the Allies “other than as a labourer” ().9 US General Lucius D. () certainly thought that domestic work fit that criterion:

This extended beyond the occupiers to victims of Nazism: Jewish women in Displaced Persons camps could be assigned or directly hired German domestics to work for them as a form of retribution (). Not only was domestic work viewed by the occupier as appropriate for the defeated and occupied, but its absence was also considered a just reward for the victor women of the occupying forces, those housewives who had been “essential workers in the victory over fascism” (). Different types of work thus aligned with the new occupation labour economy that, in turn, created new forms of ‘inferiority’.Once there was a commotion among our people, who had found that one of the scrubwomen in our headquarters had belonged to the Nazi organization for women in a very minor capacity. It seemed to me unnecessary to discharge her since I could think of no more fitting task to be performed by a former Nazi.

It was against occupied working bodies in the home that the occupier wife was to perform her role as representative of nation, democracy, and the modern (ostensibly) emancipated woman. While non-fraternisation was an impossibility in the household context, indeed in any workplace, there was an expectation to act distinct and aloof while still working towards building a new future relationship with the defeated. Occupier women (and children over 14 years) in the US zone undertook a four-hour orientation session to prepare them for their role in Germany, emphasising that they had the power “to do either good or harm” to US foreign relations (). () describes the role of women as a form of “soft-power … that both complemented and tempered the United States’ hard-power martial presence”. The occupier wives were to act as showcases of their nation’s self-perceived superior lifestyle and political/economic modernity, especially in the domestic space, as both a justification of their victory and a model for occupied German women to aspire towards. Occupier wives were not just agents of occupation power, but also of knowledge to be shared with the occupied (). The rhetoric of some women reflected the official instructions. An article from the US Weekly Information Bulletin on the American-Women’s Club in Stuttgart opened with the following words from Summer Sewall, whose husband was the Director of US Occupation Military Government Württemberg-Baden: “It seems to me a most important thing to share the spirit of democracy with young German women so that they not only can see it in us, but also can live it with us in our homes” (). What the word ‘democracy’ actually meant in the household context is more difficult to define.

Women were thus a piece in the wider game of enacting occupation power through their position of mistress in the home. While women did not have access to the corridors of power, they did have “considerable authority over the German people”, especially those in her household (). The wives were collectively presented, with encouragement and indeed instruction from occupation authorities, as a model to be seen, a tutor to be heard, and a generous provider of charity to be thankful for. But how did this play out in the intimate space of the home and, even more so, how were such interactions represented in occupation discourse, particularly in the visual archive?

3. Representations of the Modern US Occupier Wife and Occupier Home

In Images and Empires, () speaks of “alterity”, of “the idea that certain kinds of interactions tell people who they are and who most certainly they are not”. Images are important to this narrativisation, where they can be used to “draw together previously inchoate social meanings from their own societies, and then … use them to ‘recognize’ people from other societies” (). While Landau was speaking of white/non-white colonial contexts, this section seeks to apply these ideas to the asymmetrically defined occupation context, even though the comparative parties were both (mostly) white. What might images tell us about occupier–occupied interactions in the home and the power relations that defined those interactions? What tropes were used to distinguish the occupier and the occupied? The visual narratives in the chosen sources convey images of difference, uneven modernities and challenges in the female occupier–occupied relationship in the home. They are also notably divergent from more aggressive anti-Nazi/Hitler wartime propaganda, not only because they focus on women in the postwar but because they subtly convey a potential for the re-education of the now occupied. Due to the predominate symbolism of the modern, these representations are filtered below into three main themes: economic modernity, domestic modernity and modern gender relations.

3.1. Economic Modernity

The United States, as is well known, exited the Second World War as a great economic and technological power. Franklin D. Roosevelt’s “arsenal of democracy”, born of a union between industry, government and the military, not only provided the “foundations for a decisive victory” but also laid the building blocks of occupation (). Economic and technological power can be translated into the everyday feminine occupation in three main ways: as household technologies, fashion and material abundance. On the first, modified versions of household whitegoods and appliances were shipped over to Germany via the US Army for occupation households (). Considering such appliances were touted as labour-saving devices for US women in the home nation, one can construe that the role of the German domestic worker was for more than house cleaning (a body to enact power against), as were the appliances (showcases of modern technology). On the second, through its association with mass production, pursuit of the new, consumption, and desire for sophistication, fashion has been persistently connected to notions of modernity (). One newspaper reported on the popularity of US occupier women visiting the docks in Bremerhaven to catch a glimpse of the latest fashions on newly arrived occupiers (). As is made apparent in ’s () occupation novel, it was more effective to visually convey an economic contrast through the dress of women than through the uniforms of occupier and occupied men, even if the latter’s was tattered and worn. And for the third, providing access to a range of material goods was a network of commissaries and PXs (; ).10 Consumption as a measure of progress and prosperity was thus a weapon of war wielded by occupier women that linked the occupier’s household to the broader transnational economy and, due to its broad social impacts, to democracy. As () says of the occupied Japan and cold war contexts, the US housewife represented “the supposed superiority of capitalist democracy in US self-representations abroad”, while () points out that modern homes “advertised” the victor’s way of life, “showcased the American home”, and assumed the “supremacy of their nation’s ideals and institutions”. Some women did wonder how they could teach democracy by example when, in what can be described as consumption by spectacle, occupier women carried home packages of shopping full of “meat, vegetables and clanking bottles of milk” in front of the hungry Germans ().11 But the public staging of power could include both military hardware and materialism, not only as warning but also to provoke aspirational ambitions among the occupied. Performance of occupation power was often a paradoxical mix of aloof spectacle and intimate instruction, of a callous remoteness interrupted by moments of empathetic kindness. Staged images, though, were more likely to show the former.

Figure 1 demonstrates consumption by spectacle, a clear message about capitalism and economic modernity, through the bodies of two women. Taken from Life magazine in 1947, which contained a special feature on Americans in occupied Germany, this story is on the Hinkleys. Mrs. Leo Hinkley, 25 years of age, and her husband lived in a house originally built for a German officer. The couple’s unnamed domestic worker appears in the photograph in headscarf and distressed clothing, complete with bucket, broom and rag in hand, so there can be no mistake as to her servant-like role in this visual narrative. Mrs. Hinkley is in fur, heels and gloves. The image is striking in the way it assigns economic advantage as a companion to military victory through the starkly different dress of each woman. Fashion is often a marker of class differentiation (), and here we see that translated into the occupier/occupied, victor/defeated context. () conveys the experience of Simone de Beauvoir, who resented having to wear an evening gown to the theatre when visiting occupied Germany: “It seemed to her that given that the German women themselves had no evening dresses, the conquerors wore them primarily to show off what it meant not to be German”. The economic/clothing markers are intensified by the class/power narrative, exemplified through the hunched stance of the labouring woman in the background, while foregrounding the confident posture of the occupier/manager wife. The economic dimension is emphasised further by the caption, which informs the reader that Mrs. Hinkley is embarking upon a shopping expedition while the domestic worker stays to clean the house, highlighting the importance of consumerism for the victor power and the occupied’s lesser mobility. Note also the boxes marked with ‘Coca-Cola’ on either side of the stairs. These kinds of representations of wives are common, whether of the oblivious occupier woman carrying multitudes of parcels home from shopping or the US woman driving around in her imported car—another artefact of modernity. Consider the following from ’s () novel:

Figure 1.

Walter Sanders (photographer). 1947. American [Soldier] Wife, Germany. From (). Used with Shutterstock Editorial License (31 December 2022). The caption reads: “Officer’s Wife, Mrs Leo Hinkley, starts out from home for shopping trip after giving her maid instructions”.

But between the clothes of the Occupation women, conspicuous and with an air of elegance even if they came off the peg of some American department store, between their cuban-heeled and high-heeled shoes, their smart handbags, their colourful scarves, and their fur coats on the one hand, and the flat-heeled, worn shoes of the German women, their threadbare colourless overcoats, and their grey felt hats—that contrast was violent and provocative. The American women were groomed in a way that required much time and extensive cosmetic aids, and even if they wore their lipstick and rouge with moderation, they still looked like fashionable mannequins disporting themselves among the destitute and homeless.12

Such scenes were criticised then and now as evidence of embarrassing extravagance amongst poverty and destruction. Yet, it must be acknowledged that the occupier wife was doing exactly what she was brought to Germany to do—to demonstrate the economic/capitalist victor modernity that had produced such abundance and affluence, and thus also the power and prestige of her nation. Concurrently, she advertised a possible future for the occupied woman based on prosperity, freedom and peace ().

3.2. Domestic Modernity

Similar to the colonising role German women had once played in embodying German culture (; See also ), occupier wives were presented as a showcase for US domestic modernity and lifestyle. Just as the US home was paraded as the ultimate modern space in exhibitions in Frankfurt and West Berlin, so was the US housewife a celebration of pragmatic modern achievement, the United States as the “paradigmatic example of modernity”.13 The “new patriotic purpose” that women’s work had gained during the war took on an expanded transnational role during the occupation (). In a physical sense, this was accomplished in the requisitioned home primarily via the addition of household appliances but also easily transportable cushion covers, lamps and rugs, creating a middle-class consumerist environment (; ). Yet the home was also conceived as a democratic space—democracy was not seen only as a political structure, but as way of living and acting, including within the home, with the ‘American way of life’ (white and middle class) being automatically associated with US democracy, even while it concurrently carved out different spheres of influence for men and women (; ; ). How one acted in the home, including relationships between household members, was believed to be part of the ‘democratic’ performance. The occupier woman’s role in the home was both semiotic or symbolic, as a representative of her nation’s status, and performative, in acting out her nation’s domestic modernity. It is only a short step from there to entangle household practices with democratic ones, even while simultaneously performing undemocratic occupier/occupied hierarchies of power. An ‘American way’ of cleaning the house was seen as modern and democratic because it was American.

The importance of the home to both German and occupier women’s sense of self and national identity set the stage for tensions in the occupied home. The home was the demesne of the occupier wife, the kitchen her space of instruction, negotiation and, when required, battlefield. She was the mistress of her mini territory with power over ‘her’ domestic workers, a disciplining of the defeated, and when she referred to the ‘servants’ or ‘maids’ used words that articulated that power. The US woman was both a manager of labour and a tutor, expected to inculcate her staff with the modern, ‘democratic’ way of cleaning home, baking a cake, or bringing up the children, extending the tentacles of occupier-driven social, political, and economic reform into the domestic space—an extension of re-education practices with herself as an “ambassador of democracy” (). The visual sources nicely articulate her roles and the perceived contrast between the ‘modern’ occupier and ‘less modern’ occupied in the domestic space.

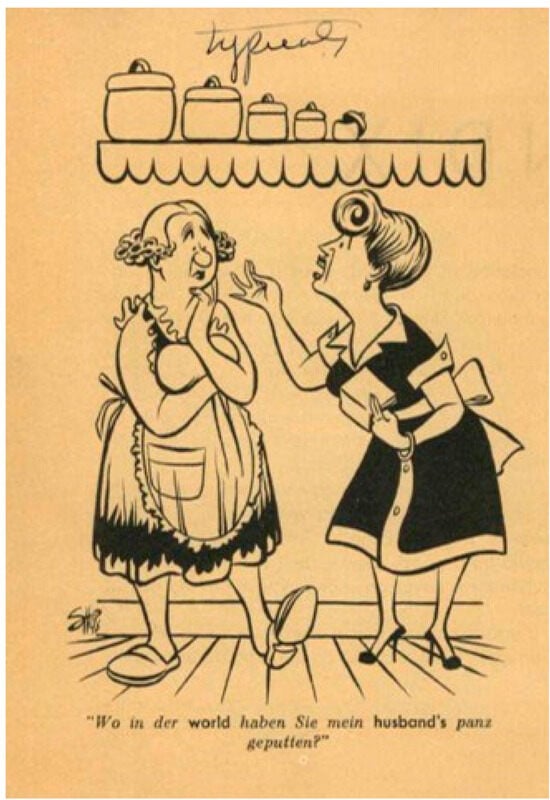

Figure 2 is of an occupier–occupied interaction, taken from a US guide for wives called An Introduction to Germany for Occupation Families, that conveys occupier perceptions of these household encounters. We are given a sense of the domestic battlefield, here over language to communicate the desires of the occupier woman and for control over the home—where are my husband’s pants, in my home? While it is presented with humour (and the former owner of this copy of the guide has written the word “typical” above the image, suggesting a relatable experience), the contrast in the representations of the two women is again quite palpable. The occupied domestic worker is frumpy, big-footed and aproned, seemingly rather confused. The US wife is not only angry or frazzled while attempting to assert her authority, but wears more modern attire with small, dainty feet. These visual representations of women’s bodies convey ideas about competing femininities—one of tradition, unfreedom, the past, and another of modernity, independence, and the present–future. This is one of three images in the same text that contrast the domestic worker and the occupier woman in this way, all, judging by their different styles, by different artists yet framing the women using the same modern/unmodern, sophisticated/rustic motifs in a class-like mistress–servant relationship. This aligns with standards of ethnic caricature that rely on “insistent repetition” and “shorthand symbols and conventions” to relay otherness, in this case to clearly demarcate the victor and defeated nations through women’s bodies ().

Figure 2.

Artist unknown, from (). US Army images created by Department of Defense personnel are fair use in the public domain.14.

Figure 3 is from another text but again shows two distinct women and the now familiar stereotyping. Operation Vittles, a recipe book compiled by US women in 1949 to raise money for German children and hospitals during the Berlin blockade, is filled with such caricatures of, and vignettes about, household encounters. Here the German domestic worker presents as old-fashioned, hair braided over her head, wearing a full apron, feet pigeon-toed and inelegant, holding forth a tray of food while looking guileless but eager to please. Her confident and slender ‘mistress’ appears in a contemporary pencil skirt and blouse with heels and a fashionable hairstyle, and is frustrated with and distressed by the presented dish, again suggesting the challenges of implementing one’s authority. The visual othering of the German domestic worker has a remarkable symbolic consistency, also acting to validate the perceived need for the occupier woman to lead her via cleaning, cooking and childminding into the modern democratic world.

Figure 3.

Artist unknown, from The American Women in Blockaded Berlin (). Operation Vittles Cookbook. Berlin: Deutscher Verlag, p. 32. With permission of the American Women’s Club of Berlin.15.

As alluded to in this image, highly contentious in this occupation was food and its rationing. Food, or a lack of it, was as much a formal demarcation of ‘us’ and ‘them’ as barbed wire fences around Allied compounds. As () states, “both the Germans and the Allied authorities drew associations between the food economy and moral categories of guilt and innocence”. One of the great attractions of working for the occupation forces was the promise of a meal, with domestic work providing even greater access to foodstuffs ().16 And shopping for, cooking, serving and eating food were fundamental parts of domestic life, so food-as-power was also at the heart of occupier–occupied interactions in the home.

Culinary power struggles in the occupied home usually revolved around the cooking and serving of food, as conveyed in Operation Vittles:

Bread was a regular point of contention, a clash over which nation’s was better. Baking cakes was also a conduit through which to perform the perceived national superiority and modernity of the occupier, for the occupier woman to act as a tutor of domestic democracy:When very heavy bread continued from her kitchen despite the family’s protests, the American housewife took over. Morning after morning she descended bright-eyed to the kitchen where she made bread with available ingredients differently proportioned. Her daily experiments successfully convinced the cook who, in self-defense, began making good bread [emphasis added].()

And in a similar example, “Although we were amazed at the German’s unfamiliarity with light cakes, most of us enjoyed mixing before an incredulous cook a beautiful light concoction destined to melt in the mouth. To see her taste the finished product was a real treat!” (). Victual mentoring was not always successful: one US wife wrote to her parents, “Well it is four o’clock and they [the children] want a cake for supper so guess I’d better go make it. Louisa [the cook] is pretty good at cooking the meals now and she has learned how to make cheese pies but she still can’t make a cake the children will eat. Guess I’m not a very good teacher”.17There are no egg custards in Germany, so German cooks and on-lookers in the kitchen, were completely dubious as to the thickening ability of the egg. When the thin soupy mixture, “No cornstarch? No flour?”—emerged from the oven perfect, the resultant expressions were well worth seeing!()

Occupier women could easily have cooked their own familiar meals, thus the prestige of being an occupier did not come from having a cook alone. German cuisine, along with German ways of keeping house, was also one of the defeated. It was as if superiority could be confirmed and democracy taught through making apple pies and white bread instead of Schweinebraten and Schwarzbrot. Considering the integral place of the Hausfrau and home in Germany’s modern history, it is further telling that US wives instructed not only their workers but also German girls in “cooking, sewing and housekeeping” in a ‘Girls’ Center’ in Frankfurt and a ‘Friendship House’ in Munich (). The message likely was that rational and efficient US ‘modern’ housekeeping practices were considered superior to ‘traditional’ German ones, and the selected images chronicle the process, often with humour, of attempting to transfer those practices to the occupied in the home.

3.3. Modern Gender and Family Relations

A third identified theme in representations of occupier wives is that of modern gender and family relations. The occupier wife was expected to display a more equitable relationship with her husband to the occupied working in the home. The aim was to counter the extreme patriarchy of Nazi gender relations, complementing other Allied programs aimed at the emancipation of German women, such as encouraging greater political involvement, workplace participation, and trade union organisation. A photograph of the Hinkleys in Life magazine nicely conveys the imagined image—husband and wife as equal partners yet with different roles, arms around each other’s waist, accompanied by their German Shepherd, Rolf, strolling towards their home for a meal during Lieutenant Hinkley’s lunch break (). (The choice of dog is interesting, provoking thoughts about whether pets, too, were part of the domestic re-education program.)

The domestic showcase extended to the smallest of the occupiers, the children. Women had a role as “mothers and educators” to impart a “democratic education” and “democratic spirit” though family relationships, and here acted as role models for German women working in the home (; ). () refers to US programs for German youth in this way, but does not apply this to the modelling role of the occupier home: “[b]y teaching young boys to assume the role of decision-makers in a democratic Germany while teaching girls to assume responsibilities as mothers and wives in democratic households, Americans projected their own postwar model of an ideal society onto Germany”. German boys were considered by the occupiers as particularly problematic due to years of Nazi indoctrination at an impressionable age. The Pocket Guide to Germany, given to US occupier men, asserted that the German boy “has been told over and over again that he is a member of the master race” (). It was thus with some glee that one woman wrote in Operation Vittles, “We have seen the [German] cook who accepted as inevitable the assistance of little girls in her kitchen, but viewed with horror little boys stepping off their masculine thrones to help in the cooky-making [sic]”. The text is accompanied by a drawing of a young boy, standing on a stool and wearing an apron, in action with a rolling pin ().

Of course, there were limitations to ideals about gender equity in the late 1940s: Mrs. Hinkley, for instance, is always Mrs. Leo Hinkley and we are never told her own name. Married women were generally not permitted to work as part of the occupation forces—the home was her occupation workplace. The showcasing of gender and family relations in the home was also often undermined by a reason the occupier wives were brought to Germany in the first place: sexual anxieties. Occupier men often assumed the sexual availability of women domestic workers, and before employed in US homes, women were “screened carefully against venereal disease”, along with other communicable diseases like tuberculosis ().

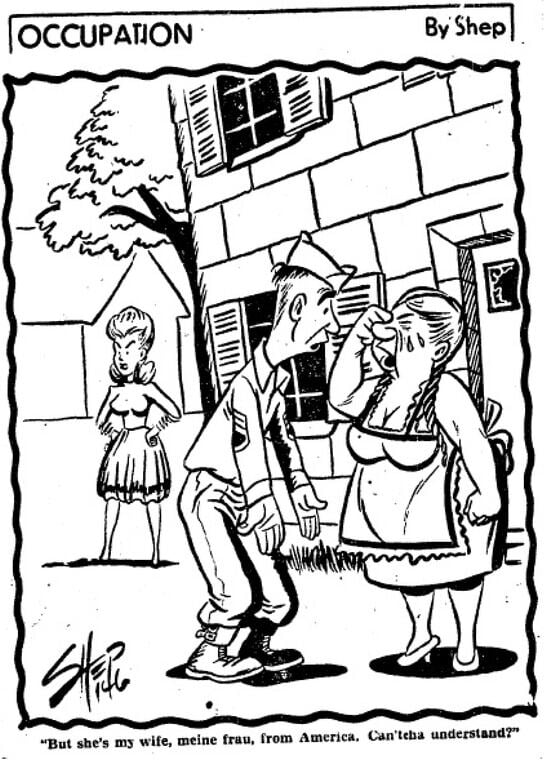

The imagined sexuality of the occupied domestic worker is discernible in occupier media representations. US publications like Stars and Stripes contained caricatures of German women, from the sexualised and Nazi-tainted ‘Veronika Dankeschön’ (note the initials) to the foolish, “fat, slovenly ’Hausfrau Hilda’” (; ). The latter was connected to the arrival of the dependents, framed as in competition for the military man’s affections. An infamous cartoon by Don Sheppard, as seen in Figure 4, shows a US soldier talking to his domestic worker and lover, ‘Hausfrau Hilda’, to explain his wife has now arrived, so presumably things were over between them. In this image, from a publication targeting occupier men, the German woman is more sexualised than others presented in this article, with bulging breasts and heeled shoes. But the other motifs are still apparent: the plaited hair, the curvy figure, the apron. In the background, the more modern, but equally eroticised, US wife stands impatiently waiting for the message to be received. () suggests the cartoon might explain “why a common bit of advice given to soldiers preparing for their families was to acquire a maid who is not ‘too good-looking’”. The occupied woman, deemed dangerous as she was yet to be liberated, was happily unequal: “Our [US] men like the old German recipe for the perfect woman: ‘Kinder, Kirche, Küche,’—Children, Church, Kitchen” (). Novelist () captures the supposed fears of the occupier woman through a conversation between protagonists Colonel T. Hunter and his recently arrived wife Betty, about the domestic worker Hunter has recently employed:

Suddenly there was a lull in the conversation. Betty had left Hunter’s last question unanswered. Instead she said, “You’ve nothing to tell me, Graham?”

“I don’t know what you mean”.

“I’m surprised at your bad taste, Graham. At your bad taste, if nothing else”.

“I really must ask you, Betty, to explain yourself”.

“You need to have established your mistress in our home. Or is that the local custom?”

The colonel leapt up. “Betty!” he said. He could not utter anything else.

The woman lit another cigarette. Her lips were trembling.

In tiresome familiarity, the perceived threat to occupier family life was often blamed on the domestic worker rather than the behaviour of the occupier man. Publications aimed at women or men often portrayed the German domestic worker in unflattering, comical and paradoxical ways—as an eager student of victor victuals or constant sexual threat. The contrast is captured again in the Sheppard example, with the occupied domestic worker cast as ‘unmodern’, available and pathetic, while the occupier wife mirrors contemporary Hollywood glamour, strength and individuality—even while being accused of depriving the US man of his pleasure.“It wouldn’t surprise me, Graham. There are sensational stories circulating back home about conditions out here. Having a mistress seems to be good form; after all, everybody knows that a German woman will sell herself for a packet of cigarettes”.

Figure 4.

(). Reproduced with permission from World Archives (4 May 2022).

There were cases where frail assumptions of occupier gender equity collapsed with tragic consequences. According to contemporary media reports, a 30-year-old US sergeant shot his German lover “in a moment of temporary insanity” in the home of her US employers. The German woman had previously worked as a domestic worker for his wife and six-year-old son (; ). A ‘maid’ was to be tried as an accomplice when she helped the US woman she worked for attack the German girlfriend of the woman’s husband—the wife attacked the woman and together they cut off her hair, “forcibly stripped her and poured a corrosive liquid on her body”(; ). In one of the most publicised cases, a US woman was tried for the shooting murder of her husband after a long period of domestic abuse. The two domestic workers in the home, where the shooting took place, appeared as witnesses in the trial. As part of the physical and psychological abuse leading to the event, the accused relayed that when she arrived in Germany with their young son, her husband informed her that he was soon to father two German children, and she had to employ a domestic worker who was one of those pregnant with his child ().18 These reports, and the media sensation some caused, well illustrate that the victor domestic ideal authorities wished to convey to the German people was often more fictional than real.

As a final note, it can be said that the home also facilitated amicable situations (). These progressed as attitudes towards fraternisation changed and the western Allies came to view their zones more as cold war collateral and future ally. As () states, “[m]any families established friendly relations with aids and nannies and even with the owners of the homes they occupied, banished to the attic or cellar to make room for themselves”.19 An interview with (), who worked as a domestic worker during the occupation era, conveys friendly relations with some of her employers. While she describes a diplomat and his wife as “cooler”—he “saw me as the daughter of the enemy”—she had “a wonderful relationship” with a US colonel, his wife and two children, who resided in Berlin. Her job was to cook and look after the children, the youngest of whom was around 18 months old. She especially enjoyed preparing for guests:

In an exchange of culinary nationalisms, Eva cooked familiar pork roast but also turkey for Thanksgiving (). She was particularly taken by the US-style BBQ and was pleased when the colonel and his wife bequeathed her their grill. Eva’s memories of working for a US couple are quite positive, and present a possible example of where the emulation of gender and family relationships in the home, within a 1940’s context, may have produced fruit, as well as breaking down wartime barriers. Yet, the desire to please one’s employer, as relayed through Eva’s memories, remains an expression of subservience to the occupier, reminding that even amicable relationships did not altogether remove the hierarchies of occupation power in the home, and neither did they provide much fodder for drawings or photographs in occupier publications during this period.First I planned everything: either a nice German meal or an American menu. Then the night before I discussed with the wife what I was going to cook. Then we had a nice soup, a first course, the main meal, dessert, wonderful fruit, in summer ice-cream, in winter pudding. Delicious. “Oh Eva”, [they would exclaim], “very much good! Very much”. I [also] made German pork roast, potatoes, many salads. Great soup.()

The selected images, and other supporting sources such as Habe’s novel, demonstrate, through the use of common tropes or language, a shared occupier understanding of relations between women in the occupier home in the US zone during the 1945–1949 period, whether as observation, imagination or critique. Such representations, in conversation with each other, act both to document these spatial interactions and communicate a shared knowledge about them. The audience is always the self, whether fellow occupiers or those in the occupier’s home nation, thus acting to reify, re-enact and reinforce knowledge and behaviour. Regardless of how widespread or even accurate such representations were, they are historical traces allowing a glimpse of occupier understandings of the practice of everyday power and of an occupation knowledge regime otherwise hidden behind the doors of the home. As stated by (), “[i]mages and the visibilities they institute are decisive in everyday meaning-making as well as in strategies and structures of power and domination”.

4. Conclusions

The first task of this paper was to give occupier wives and their roles in the Allied Occupation of Germany greater visibility. Women have always followed military husbands into places of war and occupation, but they have not always been visible in the histories of those events. This has also been the case in the post-Second World War occupations, where the scale of the family presence and the expansion of domestic help beyond the officer class was notable. The role of the married woman occupier may be seen as an extension of her elevated importance as active citizen on the homefront during the war and in domestic postwar recovery and reconstruction (; ). In Germany from 1945 to 1949, while the occupier wife continued her long-established supportive role and engaged in charity work, the domestic space was concurrently harnessed to both enact the occupier’s desired social, political and economic reforms and to stage the performance of the power driving those reforms. The home life of the occupier conveyed a supposed domestic superiority, a showcase of the victor’s power and modernity that was not only to be found in missiles and atomic bombs but also in family relations and home management. Concurrently and paradoxically, domestic work became associated with inferiority, now fit only for the abject occupied to undertake. Every US woman became a middle-class manager, while those occupied were given roles associated with the working class. Class and gender became inextricably intertwined with victory and defeat, reward and punishment.

Rather than a “mistake”, the role of the occupier wife, in her very modern “slacks and bandanna”, was not separate from masculine military power but integral to and intertwined with it. While, as () states, “women’s domestic work and wifely duties were essential to military strength”, their role went beyond this by extending the performative hierarchies of victor/defeated, occupier/occupied into the domestic space. These performances included modelling a superior modernity related to economic power/consumerism, the domestic household and associated technologies, and gender/family relations. Thus occupied Germany, despite being European and white, was subject to similar kinds of power hierarchies as non-European contexts, including in the home. Like the colonial encounter and its imperial domesticity, the occupier woman was expected to enact an occupation domesticity and perceived superior modernity in the name of her nation, with domestic workers acting as “the Other, a foil against which imperial [or occupier] status could be crafted” (). However, because a closed front door hid these performances, because they were not as visible as an imposing Allied administrative building or a victory parade, they are relatively absent from histories of the occupation era. Power is not just something that descends dramatically from above, but has an intimate relationship with the seemingly banal.

The second aim was to examine occupier wives as symbols of national power and modernity, particularly as conveyed through selected visual sources. Images, whether sketched or shot, can “compress complex intentions in economical forms … and often move more easily than language across cultural boundaries” (). They can tell us something “about cultural contact” and “peoples and power”, especially of everyday forms of power informed by class, ‘race’ and colonial practices that emphasise difference. This applies not just in the colonial contexts in which such images are often discussed, but also as translated and adapted to other asymmetrical situations, such as military occupation. In the absence of colonial skin colour codes, other cues such as mistress/worker, independence/dependence and, importantly, modernity/tradition were emphasised within the occupation context when visually representing occupier/occupied women in the occupation household. The longevity of the modern US woman narrative demonstrates the potency of these occupation tropes as they continued into the cold war, charging the Soviet Union with an inferior approach to their treatment of women. As shown by , in the so-called “kitchen debate” between US Vice President Richard Nixon and Chairman of the Council of Ministers Nikita Khrushchev in 1959, Nixon assumed that

In occupied Germany, gendered visualisations, in both caricature and staged photograph, were concise expressions of imagined occupier power that contained within them the supposed justifications for that power—as well as the promise of a changed future for the occupied.American superiority rested on the ideal of the suburban home, complete with modern appliances and distinct gender roles for family members. He proclaimed that the “model” home, with a male breadwinner and a full-time female homemaker, adorned with a wide array of consumer goods, represented the essence of American freedom.

Yet, as is subtly evident in the sometimes farcical situations conveyed in caricatures, the occupier woman was often condemned by both fellow nationals and the occupied for doing her designated and unpaid job in Germany, for acting out the prestige and power of her nation while still subjected to its gendered constraints. One explanation is that representations of women, including many of those used in this article, were documented by men and thus filtered through the male gaze. And while occupiers claimed a superior version of modernity, democracy and capitalism, as expressed through visual representations of women’s bodies, they ignored obvious connections to undemocratic practices, like British colonialism or US segregation, as inconvenient truths. Future research might be conducted into how occupier and occupied women experienced these relationships, into representations of women in other occupied zones, or on comparisons between the home in German-occupied territories and the occupied German home. Connecting these occupation images to the colonial reminds us that, while they may be different situations, including their racial contexts, the fundamentals of how that power is performed and represented remains eerily constant, not least through fragile and mobile definitions of the modern and the traditional. Thus, the occupied home in Germany, with its daily interactions between occupier and occupied women through domestic work, contributed towards wider performances of occupation power, as conveyed through visual representations of women’s bodies that contrasted the imagined relationship of each to a victor-perceived modern postwar world.

Funding

Part of this research was funded by an Australian Academy of the Humanities Ernst Keller European Travelling Fellowship (2009) and a Deutscher Akademischer Austauschdienst (DAAD) Research Stays and Study Visits for University Academics Scholarship (2009).

Institutional Review Board Statement

The protocol was approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee of the University of Wollongong, Australia (HE10/046).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

For the most part, no new data were created or analysed in this study. The exception is one oral history interview, which, due to ethical reasons, is not yet publicly available and is in the possession of the author. Stars and Stripes articles are from the NewspaperArchive.com database. British news articles are from the British Newspaper Archive. The digitised Weekly Information Bulletin (Office of Military Government for Germany (US), Control Office) can be found through several sites, including the University of Wisconsin-Madison Library. Copies of the British Zone Review are held in the Imperial War Museum, London.

Acknowledgments

I would first like to thank all the reviewers and editors who have helped to improve this paper along the way. There are many others who have offered their feedback on the article, including Bettina Blum and the UNDA Arts & Sciences Writing Group. In helping with translation and interpreting, I thank Robert Dambon and Francesca Beddie, while I am grateful to Jürgen Angelow for supporting my research while in Germany. Finally, I thank the very important interviewees who were so generous in sharing their experiences of being a domestic worker.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

Notes

| 1 | The quote is from the fictional US Colonel T. Hunter in ’s () novel, Off Limits: A Novel of Occupied Germany. Habe, a Hungarian American, was, among other things, the editor of the Neue Zeitung newspaper in the US zone during the occupation era. |

| 2 | The broader historiography on occupied Germany is too large to do justice to here. Key examples on everyday encounters are () and (). |

| 3 | For the French zones, see () and (). A 1948 interview with Sophie Kornilov, the wife of a Russian army officer in the Soviet zone, refers to few limitations being “placed on the number of servants that may be employed” by a Soviet family See (). |

| 4 | There were non-white occupier wives, particularly African American women in the US zone. This became more common over time. With the focus on the early part of the occupation and on visual narratives that privilege white occupier women, this article does not discuss the case of non-white occupier women. One author who does is (). () also make reference to African American wives, but note that they did not arrive in large numbers until the 1950s, which is outside the scope of this paper. |

| 5 | Also, see this site for a visual example from Puck magazine. |

| 6 | ’s () source for the statistic is given as Die Neue Zeitung, 11 August 1947. |

| 7 | One outcome of the reform was that many domestic workers lost their jobs (). |

| 8 | An excellent study of this is (). The similarities between Nazi aims to re-Germanise and the occupiers’ aims to de-Nazify through domestic work are uncomfortably uncanny. |

| 9 | For more on the relationship between work/labour, power and war/occupation, please see (). |

| 10 | PX is a Post Exchange, a retail store on US bases. |

| 11 | This is an adaptation of the phrase “consumption and spectacle” from (). |

| 12 | Interestingly, this is not unlike observations of “showy” Polish women made by German observers (compared to authentic tasteful German women). See (). |

| 13 | See (), () and (). These exhibitions were also aimed against the Soviet Union in the cold war context. |

| 14 | Email correspondence, USARMY Wiesbaden, 2 March 2022. |

| 15 | Email correspondence, AWC Berlin, 19 November 2019. |

| 16 | In the US zone, at first the meal was paid from the German economy and after 1947 was provided by the employing family (). |

| 17 | Julia (Jewel) Kale to Mother & Dad, November 16, 1947. In (). |

| 18 | See also Stars and Stripes issues for October 24, 25 & 26 and December 2, 16, 17, 22 & 29. |

| 19 | This paper does not interrogate the realities of relationships in the home between occupier and occupied or experiences of women. For more on this, see, for the British zone, Easingwood’s work, and, for the US zone, (), especially chapter 4. |

References

- Adler, Karen H. 2012. Selling France to the French: The French Zone of Occupation in Western Germany, 1945–c.1955. Contemporary European History 21: 577–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alvah, Donna. 2007. Unofficial Ambassadors: American Military Families Overseas and the Cold War, 1946–1965. New York: New York University Press. [Google Scholar]

- American-German Women’s Club. 1947. Weekly Information Bulletin (Office of Military Government for Germany (US), Control Office), 100, July 1947. pp. 6, 12.

- Aresin, Jana. 2021. Locating Women’s Political Engagement: Democracy in Early Cold War US and Japanese Women’s Magazines, 1945–1955. Comparativ 31: 66–81. [Google Scholar]

- Beaumont, Caitriona. 2013. Housewives and Citizens: Domesticity and the Women’s Movement in England, 1928–1964. Manchester: Manchester University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Begiato, Joanne. 2023. A “Master-Mistress”: Revisiting the History of Eighteenth-Century Wives. Women’s History Review 32: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Biddiscombe, Perry. 2001. Dangerous Liaisons: The Anti-fraternization Movement in the US Occupation Zones of Germany and Austria. Journal of Social History 34: 611–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blunt, Alison. 1999. Imperial Geographies of Home: British Domesticity in India, 1886–1925. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers 24: 421–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- British and German Women’s Activities. 1948. British Zone Review 2, June 26, pp. 18–19.

- British Army on the Rhine (BAOR). 1954. A Guide for Families in 2nd TAF [Tactical Air Force], 2nd ed. Bad Oeynhausen: BAOR. [Google Scholar]

- British Commonwealth Occupation Forces (BCOF). 1946. Know Japan. Kure: BCOF. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2019. Eyewitnessing: The Uses of Images as Historical Evidence. London: Reaktion Books Limited. First published 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Callan, Hilary. 2022. Introduction. In The Incorporated Wife. Edited by Hilary Callan and Shirley Ardener. London and New York: Routledge, pp. 1–26. First published 1984. [Google Scholar]

- Campbell, Marian Wade. 1947. GI Wife Is Outcast in Germany. The Sunday Star, March 16, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Carruthers, Susan L. 2016. The Good Occupation: American Soldiers and the Hazards of Peace. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Castillo, Greg. 2005. Domesticating the Cold War: Household Consumption as Propaganda in Marshall Plan Germany. Journal of Contemporary History 40: 261–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clay, Lucius D. 1950. Decision in Germany. Melbourne: William Heinemann Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Cole, Teju. 2019. When the Camera was a Weapon of Imperialism. (And When It Still Is). New York Times. February 6. Available online: https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/06/magazine/when-the-camera-was-a-weapon-of-imperialism-and-when-it-still-is.html (accessed on 5 January 2023).

- Cowling, Daniel. 2018. “Gosh … I think I’m in a dream!”: Subjective Experiences and Daily Life in the British Zone. In Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany. Edited by Camilo Erlichman and Christopher Knowles. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 211–29. [Google Scholar]

- Davidson, Eugene. 1999. The Death and Life of Germany: An Account of the American Occupation. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press. First published 1959. [Google Scholar]

- de Grazia, Victoria. 2005. Irresistable Empire: America’s Advance through 20th-Century Europe. Cambridge: The Belknap Press. [Google Scholar]

- de Matos, Christine. 2015. Labor under Miltary Occupation: Allied POWs and the Allied Occupation of Japan. In Japan as the Occupier and the Occupied. Edited by Christine de Matos and Mark E. Caprio. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 65–87. [Google Scholar]

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2007. “All One Could Desire”: British Women Remember Life in Post War Germany. UCLA Thinking Gender Papers. Ph.D. thesis, University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), Los Angeles, CA, USA. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/41k766w0 (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2009. British Women in Occupied Germany: Lived Experiences in the British Zone, 1945–1949. Ph.D. dissertation, Newcastle University, Newcastle upon Tyne, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Easingwood, Ruth. 2011. British Women at Work in the British Zone of Occupied Germany, 1945–1949. Women’s History Network. November 6. Available online: https://womenshistorynetwork.org/british-women-at-work-in-the-british-zone-of-occupied-germany-1945-49/ (accessed on 30 September 2019).

- Erlichman, Camilo, and Christopher Knowles, eds. 2018. Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany: Politics, Everyday Life and Social Interactions, 1945–1955. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Eva. 2010. Interview with Author, 7 June, Spandau. Interpreter: Robert Dambon. Translator/Transcriber: Francesca Beddie. [Google Scholar]

- Falzini, Mark W., ed. 2004. Letters Home: The Story of an American Military Family in Occupied Germany 1946–1949. Lincoln: iUniverse. [Google Scholar]

- Feigel, Lara. 2016. The Bitter Taste of Victory: Life, Love and Art in the Ruins of the Reich. London: Bloomsbury. [Google Scholar]

- Fleming, Joseph. 1948. Dependent from Leningrad. European Stars and Stripes, February 21, p. 29. [Google Scholar]

- France-UK-US Occupation Statute. 1949. France-United Kingdom-United States Occupation Statute for Germany. The American Journal of International Law 43: 172–74. [Google Scholar]

- Frederiksen, Oliver J. 1953. The American Military Occupation of Germany 1945–1953; Karlsruhe: Historical Division, Headquarters, United States Army Europe.

- Gerster, Robin. 2015. Capturing Japan: Australian Photography of the Postwar Military Occupation. History of Photography 39: 279–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giles, Judy. 2004. The Parlour and the Suburb: Domestic Identities, Class, Femininity and Modernity. Oxford and New York: Berg. [Google Scholar]

- Glöckner, Ann-Kristin. 2018. Shared Spaces: Social Encounters between French and Germans in Occupied Freiburg, 1945–1955. In Transforming Occupation in the Western Zones of Germany. Edited by Camilo Erlichman and Christopher Knowles. London: Bloomsbury, pp. 191–210. [Google Scholar]

- Goedde, Petra. 1999. From Villains to Victims: Fraternization and the Feminization of Germany, 1945–1947. Diplomatic History 22: 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goedde, Petra. 2003. GIs and Germans: Culture, Gender, and Foreign Relations 1945–1949. New Haven: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Griffin, Roger. 2007. Modernism and Fascism: The Sense of a Beginning under Mussolini and Hitler. London: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Grossmann, Atina. 2009. Jews, Germans and Allies: Close Encounters in Occupied Germany. Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Gulgowski, Paul W. 1983. The American Military Government of United States Occupied Zones of Post World War II Germany in Relation to Policies Expressed by Its Civilian Governmental Authorities at Home, during the Course of 1944/45 through 1949. Frankfurt: Haag & Herchen Verlag. [Google Scholar]

- H.D. 1946. The Psychology of Nazism. British Zone Review 1, September 28, pp. 8–9. [Google Scholar]

- Habe, Hans. 1956. Off Limits: A Novel of Occupied Germany. London: George. C. Harrup and Co., Ltd. [Google Scholar]

- Harvey, Elizabeth. 2003. Women and the Nazi East: Agents and Witnesses of Germanization. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hiring Germans Brings Problems. 1948. Hiring Germans Brings Problems. Stars and Stripes (Europe), August 6, p. 2. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, Maria. 2002. GIs and Fräuleins: The German-American Encounter in 1950s West Germany. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press. [Google Scholar]

- Höhn, Maria, and Martin Klimke. 2010. A Breath of Freedom: The Civil Rights Struggle, African American GIs, and Germany. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, pp. 52, 189. [Google Scholar]

- Information and Education Service (IES). 1947. An Introduction to Germany for Occupation Families. Frankfurt: HQ United States Forces European Theater. [Google Scholar]

- Instructions to Manager. 1945. Berlin Main Labour Office, 12 October, B036 4/31-3/70, Allied Kommandatura Berlin, Ländesarchiv Berlin, Germany. [Google Scholar]

- Jaima, Felicitas R. 2016. Adopting Diaspora: African American Military Women in Cold War West Germany. Ph.D. dissertation, New York University, New York, NY, USA. [Google Scholar]

- Job Seekers Drawn to MG. 1948. Job Seekers Drawn to MG by New Mark. The Stars and Stripes, June 27, p. 5. [Google Scholar]

- Kaspin, Deborah D. 2002. Conclusion: Signifying Power in Africa. In Images and Empires: Visuality in Colonial and Postcolonial Africa. Edited by Paul S. Landau and Deborah D. Kaspin. Berkeley: University of California Press, pp. 320–35. [Google Scholar]

- Kennedy, Howard. 1948. Mrs Ybarbo Admits She Shot Her Husband. Stars and Stripes (Europe), December 21, pp. 1, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Knopf, Christina M. 2015. The Comic Art of War: A Critical Study of Military Cartoons, 1805–2014. Jefferson: McFarland. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, Lee. 2017. Logistics Matters and the US Army in Occupied Germany, 1945–1949. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Kruger, Linda L. 2014. Logistic Matters: The Growth of Little Americas in Occupied Germany. Ph.D. dissertation, University of Kansas, Lawrence, KS, USA. [Google Scholar]