In recent decades, a series of philosophical and anthropological publications have problematized the divide of nature and culture in the Western world and attempted to reverse the tendency. Given the serious environmental problems we are facing, this is quite understandable. Polluted and plundered oceans, urban concrete deserts, global warming caused by carbon dioxide, and much more: should we not today emphatically demand a culture that does justice to nature, so that the two reconcile or even merge into one? Historically, the Western world must have been disrupted at some point. Otherwise, it could not have come to such a divide.

Without denying that much was disrupted, I would like to show in this essay that the divide of nature and culture in European history is more difficult to identify than one might think. Oceans can be sampled, concrete deserts mapped, temperatures measured and predicted. But “nature” and “culture” are very general, abstract terms. They have no direct counterpart. We cannot expect to locate them like two building blocks, say, that were close together in the 16th century and miles apart today.

It has long been widely agreed that the two terms are semantically sprawling and almost impossible to delimit. In the fourth volume of

Geschichtliche Grundbegriffe (Basic Concepts in History), edited in 1978 by Reinhart Koselleck and colleagues, it is said that “nature” is one of the most ambiguous terms in intellectual history. It cannot be determined empirically, but only by opposites: nature and spirit, nature and history, nature and art, nature and custom, nature and God—or, as in our case, nature and culture (

Schipperges 1978). Before that, the anthropologists Alfred Kroeber and Clyde Kluckhohn had already found that it was not much different with “culture”. Their 1952

Critical Review of Concepts and Definitions lists a good one hundred and sixty different versions of “culture” (

Kroeber and Kluckhohn 1952). Recently, Albrecht Koschorke, in his theory of narrative, also pointed out the numerous possible combinations of the two terms, as opposites or overlaps, diverging or converging (

Koschorke 2012, pp. 352–68).

This paper focuses on Philippe Descola’s approach, which is much discussed in current scholarship. The French anthropologist also considers “nature” and “culture” to be very general, fuzzy terms. Nevertheless, in his work

Beyond Nature and Culture (French original 2005), he uses them as the cornerstones of a complex theoretical edifice. He situates the small societies he studies in the Amazon and elsewhere beyond the conceptual pair, but not the Western world with its long-term history. Here he diagnoses a “great divide” (grand partage) of nature and culture. Already recognizable in Greek antiquity, the separation came to maturity around 1900, after more than two thousand years (

Descola 2013, pp. 63–66, 78).

1 According to Descola, the most important phase for the process was the period between the 16th and the early 20th century, which he traces in the third chapter of the work. It was then, he says, that the basic modern orientation of “naturalism” characteristic of Europe emerged. Representative of other writings of this kind, the following essay examines his history of separation sketched out in a good forty pages.

The next section looks at Descola’s background and outlines the methodology of this essay. We then follow the “great divide”-chapter and discuss several points: the detailed introductory example from art history, the word frequencies of “nature” and “culture”, and selected points from social and religious history. The focus is on points that allow meaningful comparisons of different societies and to which European history can offer important clarifications.

1. European History in Anthropological View

Philippe Descola, born in 1949, first studied philosophy in Paris and then switched to anthropology. Under the supervision of Claude Lévi-Strauss, the founder of structural anthropology, he wrote a doctoral dissertation on the Achuar indigenous group in the Amazon on the border between Ecuador and Peru. In the late 1970s, when he undertook the arduous and sometimes dangerous fieldwork, the warlike Achuar lived by horticulture supplemented with hunting and fishing in very remote, scattered clearings of the rainforest that were re-opened from time to time. Descolas wanted to explore the image that this group had of their natural environment and of themselves. He emphasizes right at the beginning that they did not have a coherent, canonical view of the world, so that the investigation had to “assemble” (bricoler) the structures of their representation from a wide variety of circumstantial evidence. This is especially true for the realm of the unexpressed and implicit, while the linguistically explicit can be better investigated empirically with the method of ethnoscience. Ethnoscience and ethnobiology are the designations used to refer to the terminological recording of the environment, which Descola compared with Western taxonomies partly compiled by himself. As one can easily imagine, the investigation was very laborious due also to the limited linguistic understanding (

Descola 1994, pp. 2, 7–8, 62–63, 332–33).

2Descola’s later work

Beyond Culture and Nature, which interests us here, begins with his experiences among the Achuar and returns there again and again. Together with many other small societies that the anthropologist knows from literature, it forms a background for his view of European history. In the two decades between the two publications, the concept of ontology had emerged in part of anthropology, which is also intended to give political dignity to the worldview of the Amazonian small societies in their confrontation with the encroaching white immigrant society. Accordingly, the Achuar ideas, reconstructed under difficult circumstances, have solidified into an “ontology” in the new book. They now stand for the “animism” that had been rejected as a concept in the dissertation (

Descola 1994, pp. 98–99). The “naturalism” diagnosed by Descola in Europe has now also become an ontology, for the author intends to run through the whole spectrum of conceivable human-environment relations and to bring them to a unified denominator. For this purpose he uses two more ontologies, totemism and analogism (

Descola 2013, p. 122).

In Europe, the term “ontology” has long been common, but it usually refers to particular approaches and traditions of philosophy. One of the difficulties in Descola’s historical account concerns his unclear general level of reference. Is naturalism a particular social construction of reality, or is it so closely related to a mode of existence that one can speak of an ontology in this new anthropological sense?

3 In our chapter on the “great divide”, however, the author holds back, preferring to use the term “cosmology” and other less marked words. The chapter begins with a look at historical representations of landscape and then deals in loose chronological order with six domains that he addresses as autonomous: the autonomy of

phusis, the autonomy of creation, the autonomy of nature, the autonomy of culture, the autonomy of dualism, and the autonomy of worlds.

Before we begin reading, I would like to introduce a second interlocutor. Keith Thomas, born in 1933, is a very distinctive, highly decorated British historian with a flair for anthropological topics. Among his many works, two of note here are

Man and the Natural World. Changing Attitudes in England 1500–1800 (

Thomas 1983), published in the U.S. with the subtitle

A History of the Modern Sensibility, and

In Pursuit of Civility. Manners and Civilization in Early Modern England (2018). Keith Thomas has also been interested in anthropology since his student days. Inspired by Edward E. Evans-Pritchard, he published general reflections on the relationship between the two disciplines as early as 1960 (

Thomas 1960). Of particular importance to Thomas was practice-related British anthropology. He used it as inspiration to examine his own history from a large number of sources. In fact, he cites so many historical witnesses that one feels transported back to a well-populated marketplace in the early modern period. At the same time, he gives clues as to how the intellectual views he elaborates fit into the broader cultural and social history. For us, Thomas represents an indigenous European voice that we can bring into conversation with the more outside voice of Descola.

4 For reasons difficult to understand, the latter does not seem to have consulted the British text.

In this essay, I want to make up for this omission after the fact and explore what a conversation between the two protagnoists might lead to. First, I discuss the art-historical example with which Descola introduces his “great divide”-chapter.

2. Prelude in the Mountains

To make the emergence of the modern conception of nature immediately comprehensible by means of an example, Descola begins his separation narrative with a drawing from about 1606. It is a little piece by the Flemish artist Roelant Savery, then working at the imperial court in Prague. The drawing shows a bare mountain landscape, almost devoid of people, with only a small artist in the foreground sketching the landscape. According to Descola, the appearance of the rocks, the stepped relief of the ground, and the location of the fields and houses indicate that the drawing reproduces a real view, seen in perspective, “although possibly a little foreshortened so as to accentuate the vertiginous character of the mountain” (

Descola 2013, p. 57).

The drawing, Descola continues, expresses a new distance between man and the world, using linear perspective developed one hundred and fifty years earlier. At the same time, under the influence of Pieter Bruegel, the artist shows a mountain range devoid of people and, with the existence of the draftsman, suggests another perspective in addition to the perspective visible to viewers. This is a “double objectivization of reality” and thus an illustration of manifold movements of the 16th and 17th centuries: withdrawal of the subject from nature, mathematization of space, subjugation of reality with newly invented instruments. In short: “Nature, now dumb, odor-free, and intangible, had been left devoid of life” (

Descola 2013, pp. 58–61).

Historical sources tell us that Roelant Savery also traveled to Tyrol between 1606 and 1608 to study the alpine “wonders”. He was known as a painter of the living environment. In his largest painting he captured 44 different animal species and 63 plant species. That he consciously applied linear perspective may be readily assumed with Descola. He also mastered the new oil technique that had emerged since the 15th century, with its refined overpaintings and the use of canvas instead of wooden panels. In addition, he was versed in various genres of painting that had developed at that time. Nevertheless, it is doubtful that Savery is a convincing example of a separation of nature and culture. Rather, we see an artist who was intensely concerned with both the animate and inanimate worlds. If we want to express his preoccupation in binary simplified terms, we must say that historically it was about approaching nature, not separating from it.

5There are dozens or even hundreds of books on the representation of the landscape and the mountain in the history of art. They have titles like

The Discovery of Landscape,

The Invention of Landscape, or (in the technical 19th century)

The Conquest of Landscape. So far, I have not seen a title in this genre that alludes to the separation from nature through new modes and techniques of representation.

6 The connection with new interests of elites and afterwards a broad population is too obvious. Bruegel, Savery and many others, later for example William Turner and Giovanni Segantini, made sketches and sometimes whole paintings in the wild and in the mountains. Their written legacy is full of references to their passion. In the Alps, the rush to the mountains can even be quantified in a makeshift way. While we know of 21 documented first ascents for the 16th century, there were 1220 in the 19th century (

Furter 2005, p. 96). Keith Thomas put it in a nutshell when he wrote: “By the later eighteenth century the appreciation of nature, and particularly wild nature, had been converted into a sort of religious act” (

Thomas 1983, p. 260).

According to Thomas, this appreciation of nature was also expressed in painting and in the art trade. Since the late 17th century, there was an established market in England for landscape engravings, which the middle classes hung on their walls. The more the 18th century progressed, the more the engravings also showed wild nature (

Thomas 1983, pp. 265–66). Our interlocutors thus classify things differently, and this difference runs through other questions to be considered here: While the anthropologist, according to his theoretical ideas, almost automatically focuses on autonomy and separation, the historian uses countless documents to show how the motherland of industrial modernity grew beyond a limited anthropocentric perspective in the early modern period and began to take an interest in nature for its own sake. In what follows, we first address the linguistic dimension and then turn to aspects of the history of religion and science. Since the basic question refers to the classification of worldviews, an overview of the linguistic development is a prerequisite for the analysis of other aspects.

3. Nature and Culture—An Unequal Pair of Words

When terms are as abstract and vague as “nature” and “culture”, it is advisable to take the historical use of language very seriously. Words are good indicators. We can puzzle over what they mean. But we cannot argue about whether they occur in the text at all, as with preconceived concepts that the history of philosophy likes to use. When Descola made his elaborate ethnoscience recordings in the Amazon, he started from the use of language, and only in a second step (re)constructed the more or less implicit worldview of the Achuar.

“Nature” and “culture” were learned words in Europe, adopted from Latin, and generally used only by the elites until around 1900. Among the lower classes, “nature” had not least sexual meanings, as a taboo word for sex drive, procreative power, menstruation, sperm, and genitals. We can assume that this expression came to the people via doctors and advice literature.

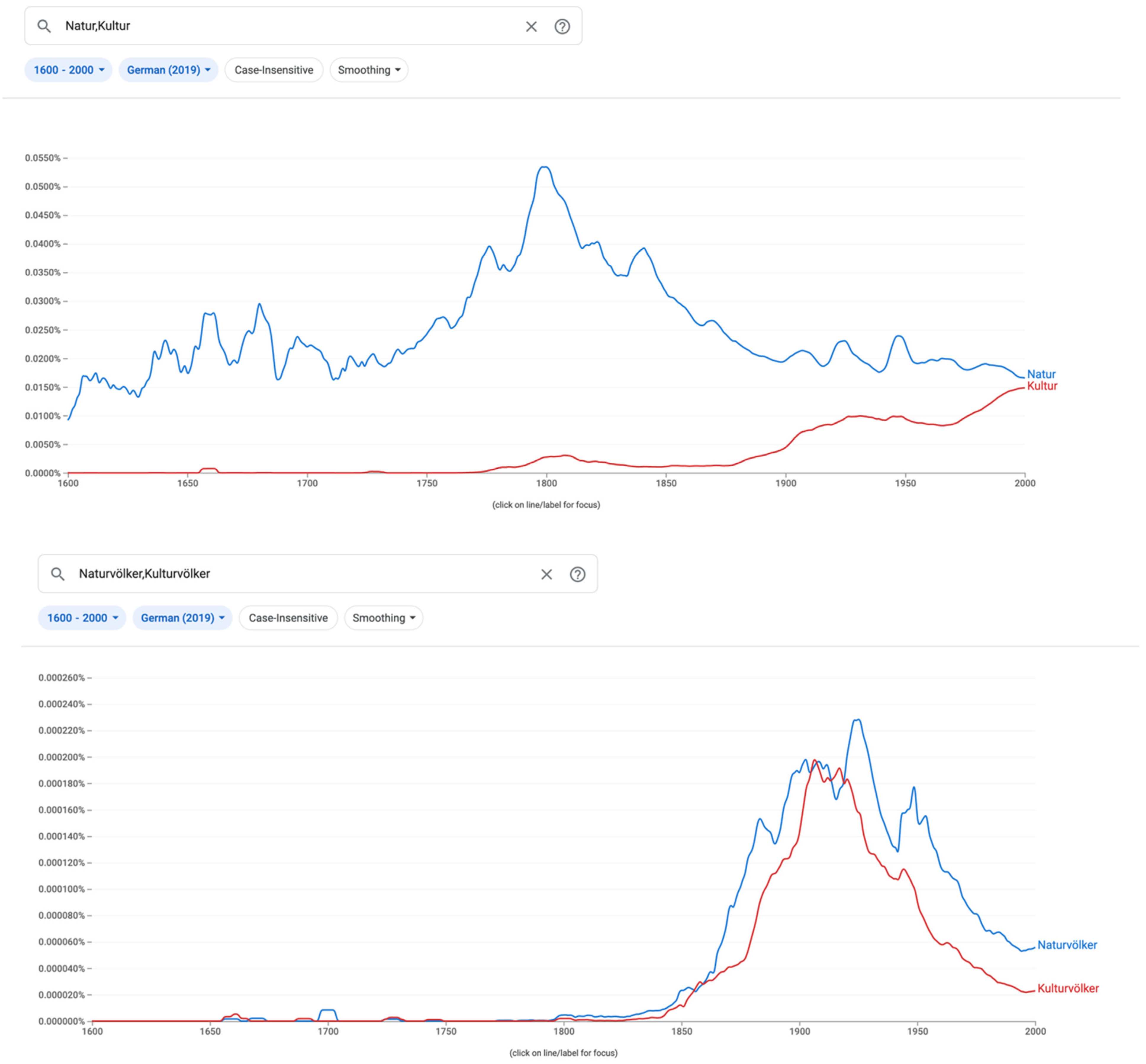

7 In general, the chronology of usage was quite different. While “culture” did not really emerge until 1770 and then especially in the 20th century, “nature” was already present in the 16th century. With the rise of natural history, it was used more and more often. According to Ngram Viewer, the peak of word frequency in the digitized printed materials of Google Books was around 1800 (see

Figure 1).

8 Here it is advisable to start from German, because in this language “culture” was not rivaled by “civilization” to the same extent as in English and French, and because the German word pair “Naturvölker”/”Kulturvölker” (nature/culture peoples) expresses the imperialist phase most clearly.

As is known, authors of the Late Enlightenment, before and around 1800, produced a series of writings that claimed to be a “system of nature”, in individual cases even a “catechism of nature”. The French Revolution brought about a sharp politicization of the concept of nature. This intense debate can be clearly seen in the frequency of words. Contrary to what one might think, in these writings people were not regularly conceived as an external component. There were also authors who identified them as an inseparable part of nature, like the Baron d’Holbach in a work from 1770 (

Schipperges 1978, p. 233). Those who do not look for just one word, but for the word pair, have more problems. The late emergence of “culture” means that substitute words must be employed if one is to interrogate the early modern period. Descola (like others) uses mainly “man” or “society” as surrogates (

Descola 2013, p. 70). This is justifiable. However, one should be aware that “culture” is thereby further diluted, because the substitute words, despite overlaps, also cover other fields of association.

Descola does not come across a text that literally juxtaposes nature and culture until the end of the 19th century. The German philosopher Heinrich Rickert gave a lecture on cultural and natural sciences (Kulturwissenschaft und Naturwissenschaft) at the Kulturwissenschaftliche Gesellschaft of Freiburg in 1898, which he published, later reworked, and greatly expanded. The book was quickly successful and appeared in many editions. This was the moment when the pair of words became historically operative and actually contributed to the classification in Western “cosmology”, but in the narrow field of philosophy of science. Here, linguistically, it can be argued with good reason that nature and culture took separate paths. This was also often interpreted in this way. Rickert himself disagreed. It is quite unjustified to say that this approach tears apart the unity of science, the philosopher held in the 1926 edition: “On the contrary, I have precisely shown how, despite the logically different tendencies of scientific conceptualization, the many special disciplines can be methodologically combined into a unified whole” (

Rickert 1926, p. VIII; my translation).

As shown on the graph of word frequency, the talk of (high) “Kulturvölker” versus (low) “Naturvölker” emerged around 1800, intensified massively in the imperialist phase of the late 19th century, and declined after the First World War. The hierarchized pair of words became a means in a global struggle fought also with other expressions. Keith Thomas devotes several chapters to it in his study of “civility”, a parallel term to “culture”. In the 19th century, he argues, the dominance of British economic and military power produced a huge self-confidence and an absolute trust in the superiority of Western civilization. “It confirmed the widespread disdain for the ‘backward’ peoples of Asia and Africa and strengthened the assumption that it was entirely acceptable to suspend conventional standards of civil conduct when dealing with them”. Despite many cautionary and critical voices, the opinion that the world was divided into civilized and barbarian peoples was almost as widespread as at the beginning of the early modern period (

Thomas 2018, p. 295).

One learns surprisingly little from Descola about this aspect, which particularly concerns the small societies he treats. Only at the end of the book does he mention the “revolting disparity” between the conditions of existence in the global South and North. They are not, he says, the subject of his anthropological theory (

Descola 2013, p. 405). But it can be assumed that they were part of its historical background. The talk of ontology that Descola half-heartedly takes up undoubtedly places itself in the struggle of indigenous groups and nations for self-determination that has emerged since the mid-20th century and has been fought out in many places. As anti-colonial and indigenous movements gained strength and Western views went on the defensive, the conceptual pair of nature/culture took on new meaning. It now became a handicap because it was seen as expressing a dualistic rather than a holistic worldview. The “divide from nature” developed into an important theme and sometimes, as with Descola, into a main characteristic of European history.

9 4. Who Has Which Soul?

A possibility of insightful comparisons is offered by the concept of soul. When Descola worked on the field study of the Achuar in the Amazon, he translated the indigenous word “wakan” with French “âme” (from Latin “anima”), i.e., “soul”. Not only did the people of this group possess such a soul, but also the majority of plants, animals and celestial bodies. However, not all of them were endowed with it in the same way. Depending on the possibilities of the communicative exchange between them, there were fine gradations. The dialogues were not only dependent on the production of sounds and the sense of hearing. According to Descola, intersubjectivity was also expressed in a “discourse de l’ âme” (speech from the soul) that overcame language barriers and transformed plants and animals into meaning-producing subjects, except when communication could not function due to a defect of the soul or for reasons of distance (

Descola 1994, pp. 93, 98–99, 324–25).

In

Beyond Nature and Culture Descola returns to this more-than-human concept of soul of the Achuar and underpins with it his ontology of animism. At a theoretical point, however, he now relativizes the close relationship and assumes a universal separation between a level of “interiority” and a level of “physicality”. These concepts are introduced by him in order to schematize his four ontologies in a matrix of difference and similarity. A gradual difference between European naturalism and the other ontologies remains, however, because the universal and universally variable dualisms of interiority and physicality are, according to Descola, most pronounced in Western modernity (

Descola 2013, pp. 115–22).

But who had a soul in this “most dualistic” Western modernity? Keith Thomas reports that the conception of the soul of ancient philosophers was taken over by medieval scholasticism and fused with the Judeo-Christian doctrine according to which human beings were created in the image of God (Genesis 1:27). “Instead of representing man as merely a superior animal, it elevated him to a wholly different status, halfway between the beasts and the angels. In the early modern period it was accompanied by a great deal of self-congratulation” (

Thomas 1983, p. 31). Nevertheless, there was a striking disagreement in the period as to what exactly constituted this unique superiority of humans over animals. The intellectuals brought into play the most diverse characteristics. One of the most remarkable attempts to magnify the difference came in the 1630s from René Descartes. The bodies of humans and animals were machines or automata; only humans possessed additionally an immaterial soul. Among the reasons for the resonance of this theory, according to Thomas, were its religious harmlessness (animals were therefore not immortal) and its justificatory character for a brutal treatment of animals in everyday life. However, Cartesianism remained controversial and temporary. In England, many later intellectuals followed John Locke and John Ray, who rejected the notion of animal-machines as “against all evidence of sense and reason” (

Thomas 1983, pp. 33–35).

As Thomas goes on to explain, this tendency toward a more animal-friendly worldview was fostered from the 17th century onward by the increasing keeping of pets and domestic animals. First in the aristocracy, then in wider circles, these personal animals, dogs in particular, took up more and more space. Thus, the last bastion of an unbridgeable barrier between humans and animals also began to falter: the uniqueness of the human soul. On the level of popular religiosity, this was not a problem, because the intellectual distinction between creatures with and without souls had never really penetrated the peasant population. Even on the theological level there were possible approaches. Had not Paul spoken in Romans (8:21) of the entire creature being redeemed on the last day? Could animals therefore be immortal? In the 17th century, such an interpretation was considered an affront; in the course of the Enlightenment, it became more acceptable. In the 1770s, an Anglican clergyman declared that animals possessed real souls, stating “that he had never heard an argument against the immortality of animals which could not be equally urged against the immortality of man” (

Thomas 1983, p. 140).

10 5. Anthropocentrism Eroding

Thus, in Keith Thomas there are definitely certain “divides from nature”, yet not one big general one as in Philippe Descola, but several sectorial and temporary ones. They do not determine the overall direction of development. For Thomas, this runs from a “breathtakingly anthropocentric spirit” to a more open view of nature also “for its own sake”. He describes as breathtakingly anthropocentric sermons of the 16th and 17th centuries that presented the whole natural world as a direct response to the Fall. It was only because of the Fall that wild animals were wild, that there were hideous reptiles, and that farm animals had to endure a miserable life of beatings. The domination of man was the central point in God’s plan. Man formed the goal and purpose of the divine creation, everything was arranged for him (

Thomas 1983, p. 18).

While Descola wants to derive a general cosmology from the history of philosophy and science, Thomas—interested in social history—puts much emphasis on religion. This was the cosmology of which the general population actually learned and had to learn something in church services and other religious occasions. It was also the horizon of thought for intellectuals and naturalists. From them came the most important impulses for change. In a social-historical view, one should ask at each step how many people the innovations could affect. At first, the learned treatises undoubtedly went over the heads of the vast majority (

Thomas 1983, p. 36).

According to Thomas, the gradual erosion of comprehensive anthropocentrism during the early modern period can be traced to a combination of different developments. Some were already underway at the beginning of the period, others came later. First he cites the emergence of natural history with a new zoological and botanical curiosity (

Thomas 1983, p. 51). Instead of using fauna and flora primarily as symbols for the human sphere, as had been the case in the past, there was now an increasing search for other, more objective classification criteria. “Each of these classificatory schemes represented an ambitious attempt to impose a new form of intellectual order upon the natural world, to reduce ‘all kinds of animals and vegetables into method’, as a contemporary put it”. For plants, John Ray’s classification became established in the late 17th century and was superseded from about 1760 by the system of Carl Linnaeus, before “more natural” taxonomies emerged again around 1810. However, the rival classifications continued to operate with analogies between humans and the environment. They were organized hierarchically and followed familiar concepts of order. Thus, in the anglicized Linnaean system, there was a “Vegetable Kingdom” subdivided into various “Tribes” and “Nations” (

Thomas 1983, pp. 65–66).

One might think that classification would be the ideal setting for Descola to profile his “great divide” in naturalism. However, many scientific classifications also included humans. Therefore, he helps himself with the explanation that the general diversification of the criteria serves to conceal the “crude ontological origins” of the fundamental divide and to “restore humans to the field of natural history” (

Descola 2013, p. 244). Thomas does not have to rely on such a circumstantial explanation. For him, the new approaches are an attempt at less interest-driven views of nature. The researchers, he says, were far from separating the natural world entirely from the human world. In the end, however, they challenged the self-assured anthropocentrism of the previous period. “By 1800 the confident anthropocentrism of Tudor England had given way to an altogether more confused state of mind. The world could no longer be regarded as having been made for man alone, and the rigid barrier between humanity and other forms of life had been much weakened” (

Thomas 1983, pp. 89, 301).

6. Conclusions

How great was the “great divide” of nature and culture in Europe highlighted by Philippe Descola? With his narrow approach rooted in the history of philosophy and science, this question cannot really be answered. If “naturalism” was to represent a cosmology, or even an ontology, in European history and the present, one would have to ask more broadly about the social anchoring of these concepts. For this purpose, linguistic clues are of importance, for they reflect most clearly the basic categories of historical actors. Until the 19th century, they hardly ever seem to have explicitly contrasted “nature” and “culture”. Descola has anthropological experience and is interested in theoretical construction. He lacks equally intense historical contact with indigenous Europe. And paradoxically, he should not be fully reliant on this great divide of nature and culture anyway, for in the course of the study he introduces a universal distinction between physicality and interiority.

The historian Keith Thomas also sees a great divide, but this was at the beginning of the study period and was religiously based. It formed a legacy of the Christian tradition and made of mankind (especially its male part) not only higher creatures, but a caste quite distinct from the rest of creation. Due to scientific development and other factors, the anthropocentrism of the 16th and 17th centuries weakened; historical actors began to take an interest in the environment in a variety of less self-centered ways. Since the late Enlightenment and Romanticism, this led to nature-oriented popular movements on which later environmental protection built. When Thomas speaks of nature and culture, he does so in concrete contexts that give support to the expressions.

11 He would not be carried away by a rhetorical philosophy of a general “rapprochement of nature and culture”.

Whether divide or rapprochement—it has become clear that the complex developments of environmental perception cannot be reduced to a simple spatial relationship between two abstracta. Incidentally, it would not be a foregone conclusion whether an all too violent rapprochement with nature would not have contributed to the manifold problems with which we are confronted today and which lead to a justified desire and a widespread longing for something different.