Artistic Transfers from Islamic to Christian Art: A Study with Geographic Information Systems (GIS)

Abstract

1. Introduction: Artistic Transfer in the Late Medieval Mediterranean

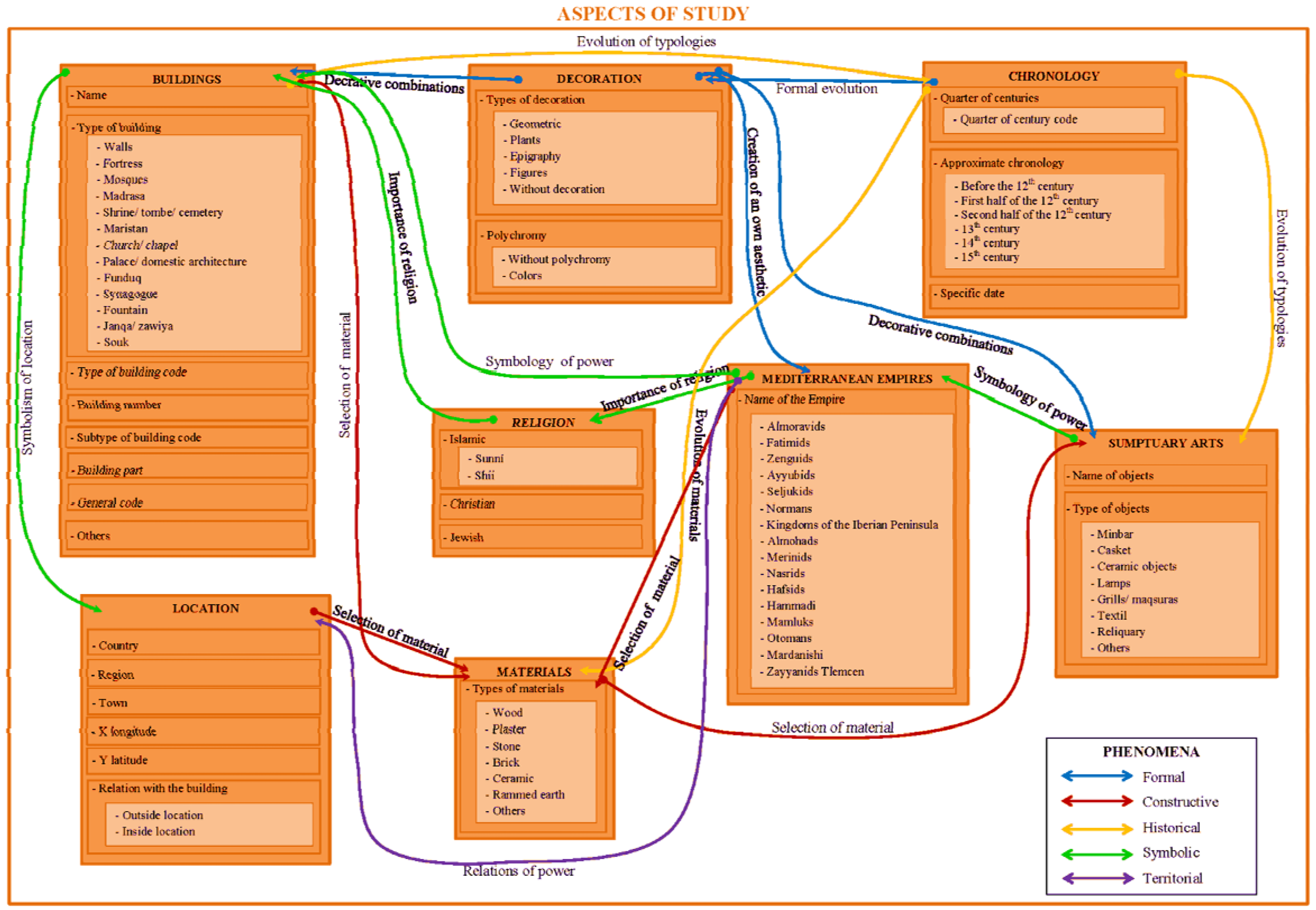

2. Methodological Aspects of the Study of the Artistic Transfer

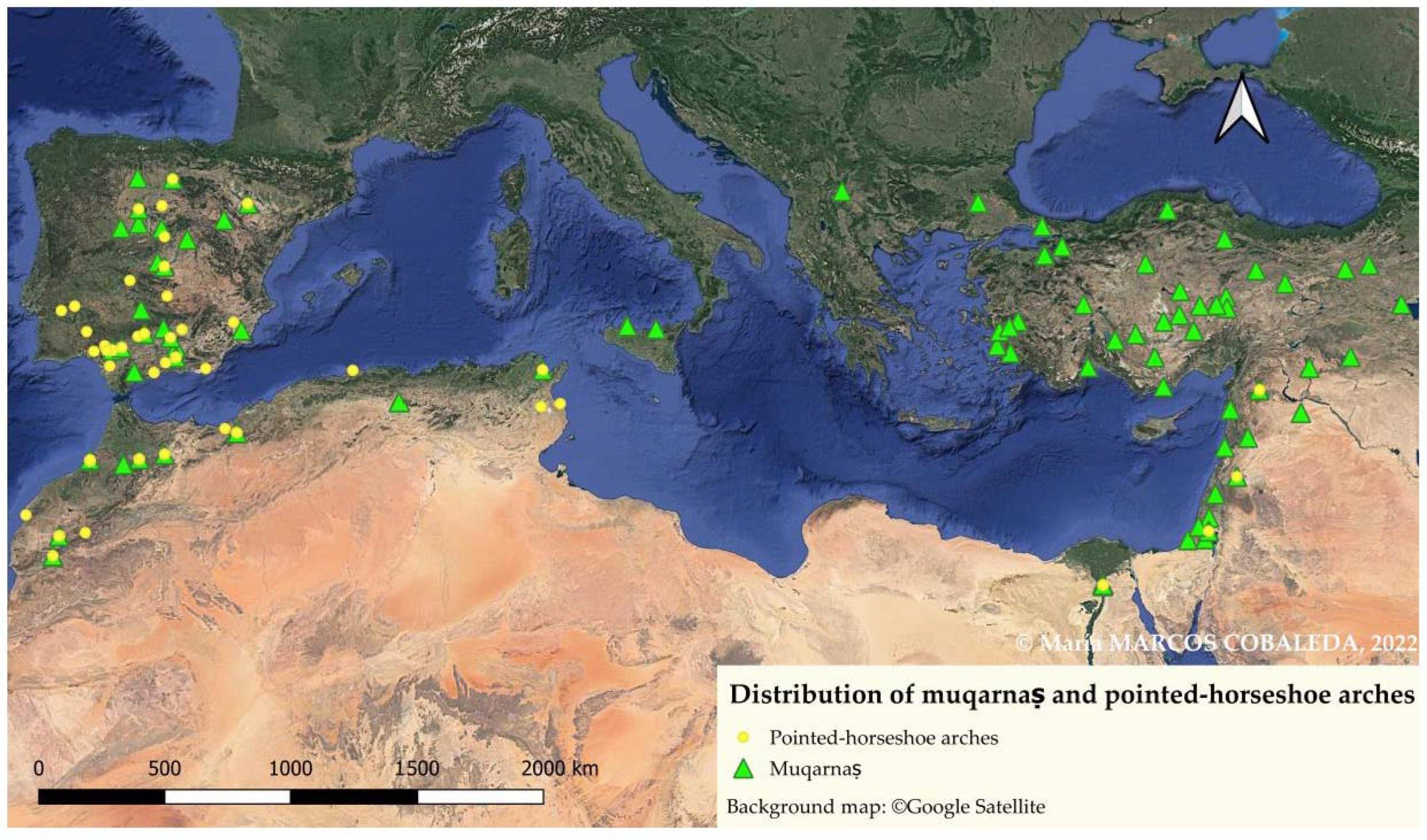

3. Distribution of Muqarnaṣ and Pointed-Horseshoe Arches throughout the Mediterranean Basin

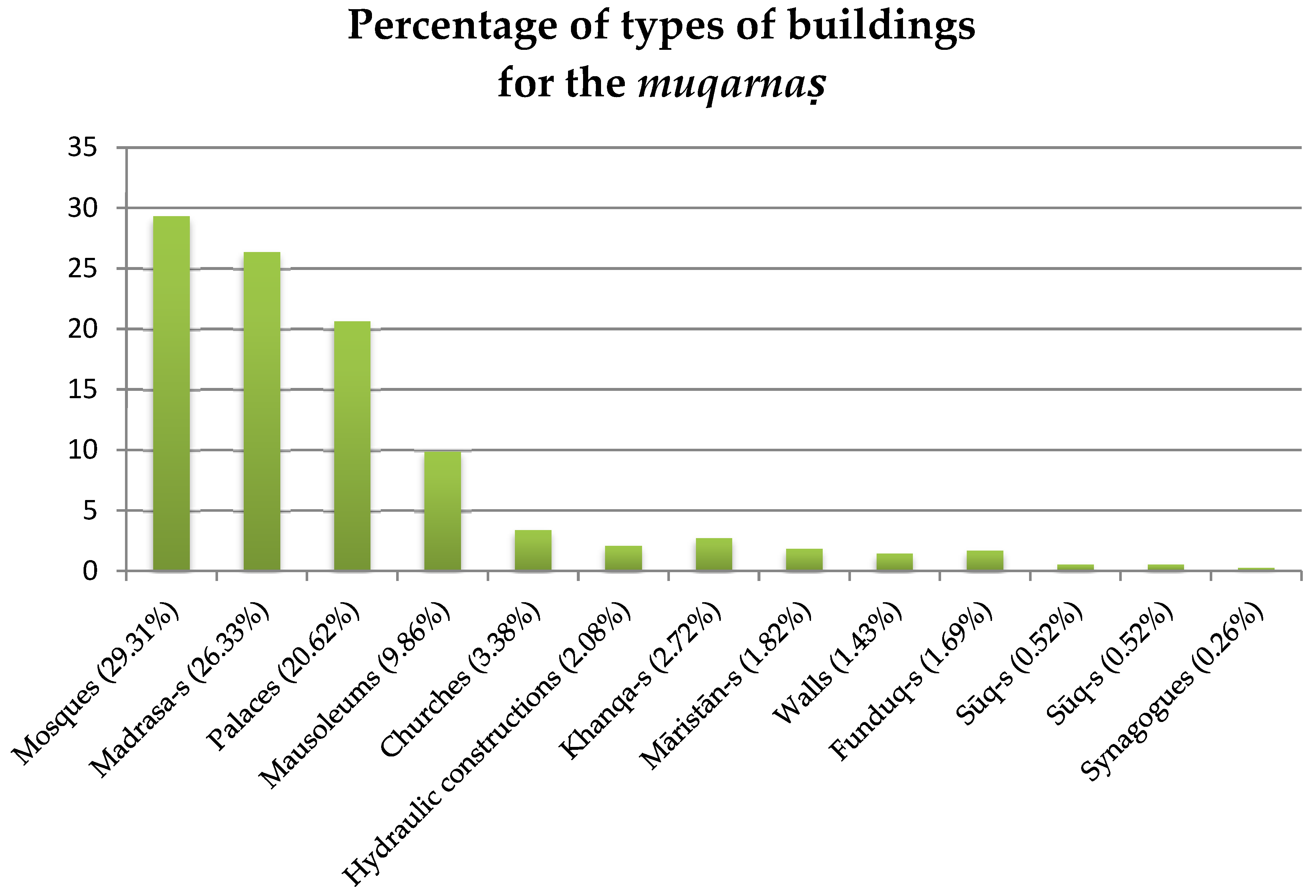

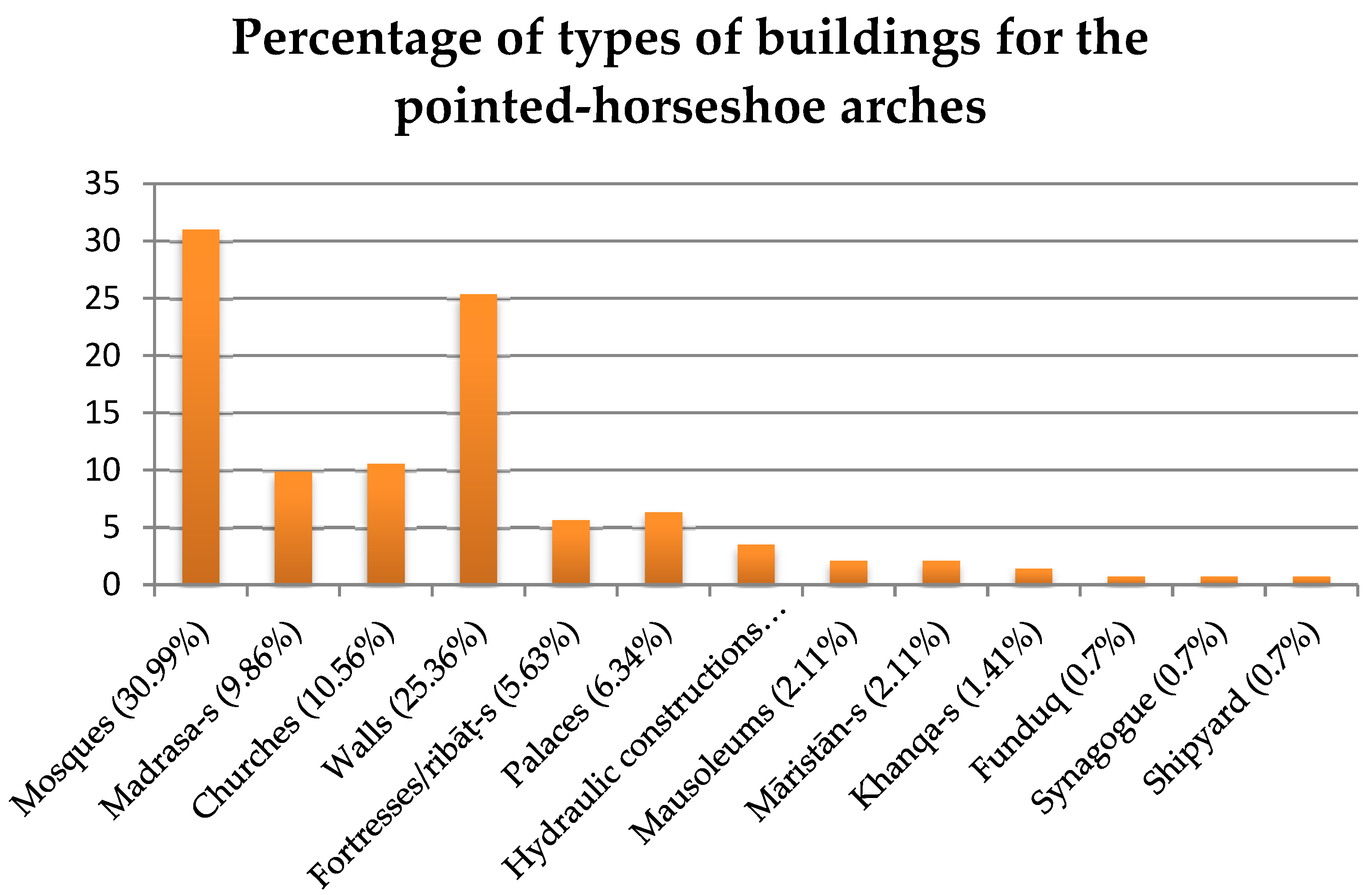

3.1. Types of Buildings Where Muqarnaṣ and Pointed-Horseshoe Arches Are Found

- 26 in a total of 18 churches or Christian chapels (3.38%);

- 16 ensembles in 12 hydraulic constructions (2.08%);

- 21 in a total of 9 khanqa-s or zawiya-s (2.72%);

- 14 ensembles are located in 7 māristān-s (1.82%);

- 11 ensembles in 7 walls (1.43%);

- 13 ensembles in a total of 7 funduq-s (1.69%);

- 4 in a total of 3 sūq-s (0.52%);

- 2 ensembles in a total of 2 synagogues (0.26%) (Chart 1).

- 9 ensembles in 9 palaces (6.34%);

- 5 in 5 hydraulic constructions (3.52%);

- 3 ensembles in 3 funerary architectures (2.11%);

- 3 ensembles in 3 māristān-s (2.11%);

- 2 in 2 khanqa-s or zawiya-s (1.41%);

- 1 ensemble in 1 funduq-s (0.7%);

- 1 ensemble in 1 synagogue (0.7%)

- 1 ensemble in 1 shipyard (0.7%) (Chart 2).

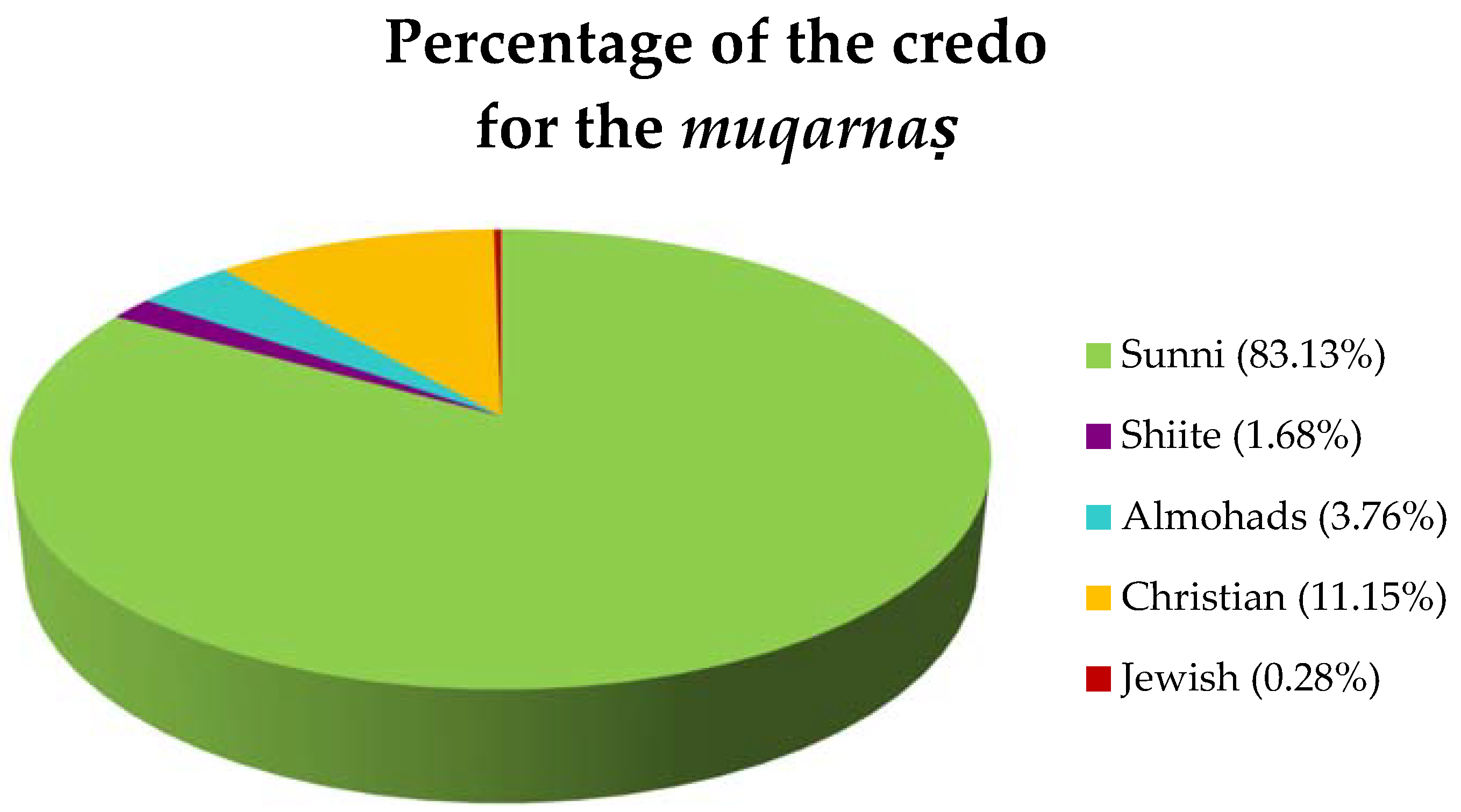

3.2. Results of Analysing the Credos of the Empires That Built These Constructions

- 641 ensembles built by Sunni societies (83.13%);

- 13 ensembles of muqarnaṣ built by Shiite societies (1.68%);

- 29 ensembles of muqarnaṣ built by the Almohads (3.76%);

- 86 ensembles built by Christian societies (11.15%);

- 2 ensembles built by Jewish societies (0.28%) (Chart 3).

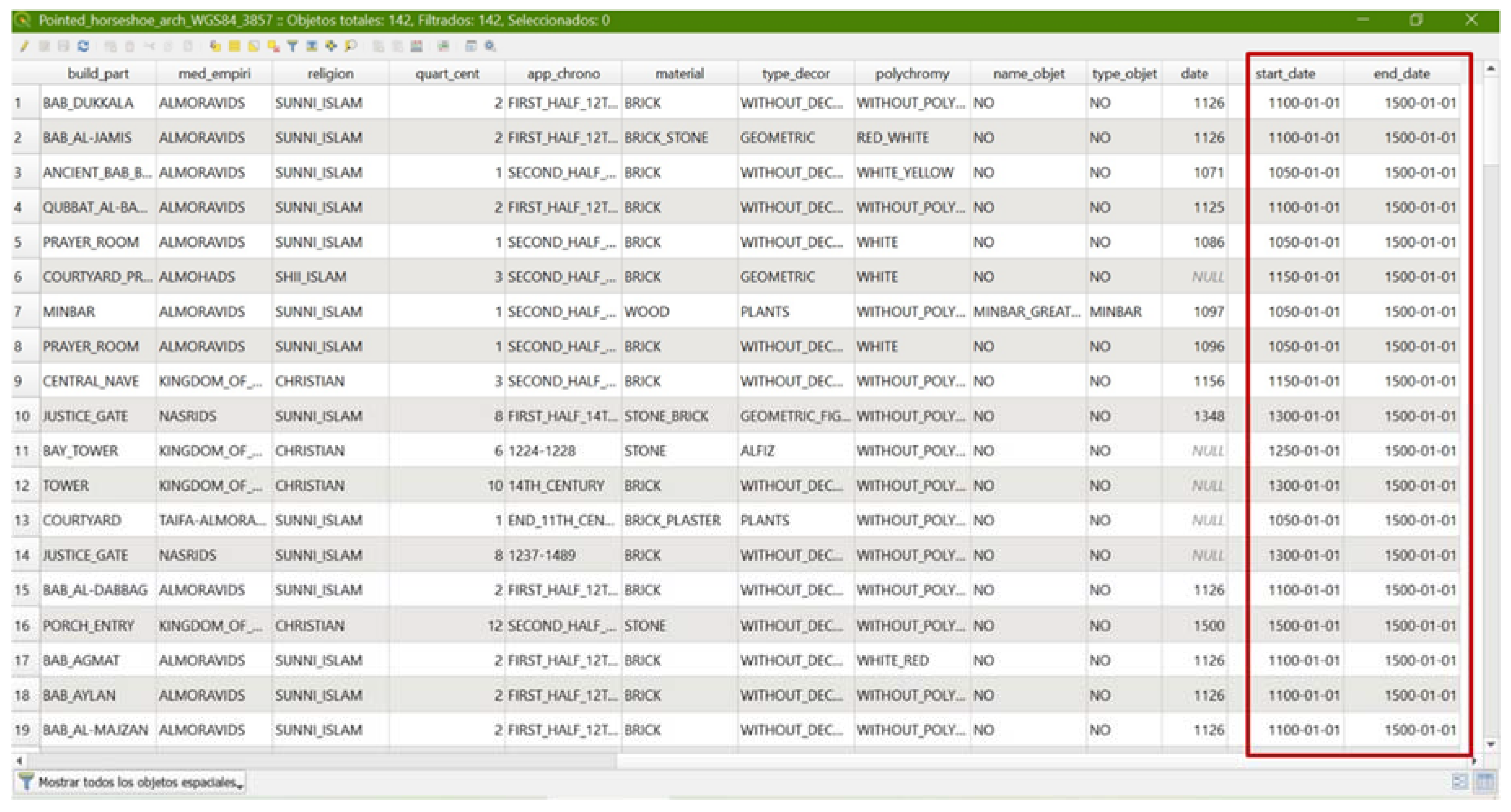

3.3. Results of the Chronological Distribution of Muqarnaṣ and Pointed-Horseshoe Arches

4. Discussion

5. Preliminary Conclusions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | This research was framed by different research projects, among which the ArtMedGIS Project (MSCA—H2020, grant agreement No 699818) can be highlighted. This project was developed at the Instituto de Estudos Medievais (IEM—FCSH/UNL, Lisbon) in collaboration with the Laboratoire de Démographie et d’Histoire Sociale (LaDéHiS—CRH—EHESS, Paris) and the University of Granada between 2016 and 2018. For more information about the project, see ArtMedGIS Project (2016–2018). |

| 2 | For a more comprehensive analysis of the exchanges between Christian Kingdoms and Al-Andalus, see (Cabrera Lafuente 2019; Rodríguez Peinado 2017; Yarza Luaces et al. 2005; Calvo Capilla 2017a, 2007b; Marcos Cobaleda 2021). |

| 3 | Many works have been published on Mudejar art, as G.M. Borrás Gualis (2005, 2012, 2017, 2018), R. López Guzmán (2006, 2015, 2016), Mª E. Díez Jorge (2001, 2007, 2014, 2016) and F. Giese (Giese 2021; Giese and León 2020). |

| 4 | This structure consists of a square room covered with a dome. It is widely used in Islamic architecture, above all for spaces with an outstanding character. Its use is also documented in the Christian context linked to the Mudejar architecture. |

| 5 | The incorporation of these Abbasid elements into western Islamic art during the Almoravid period can be explained by the loyalty to the Abbasid Caliph that Almoravid emirs showed since the beginning of the movement, especially in times of the emirs Yūsuf Ibn Tāshufīn and ‘Alī Ibn Yūsuf (De Felipe 2014). This relationship makes the Almoravid movement a part of the Sunni revival that took place in the Mediterranean framework during the 12th century (Tabbaa 2001). In this way, the Almoravid emirs made use of the artistic language as a transmitter of Sunni principles and aesthetics (Marcos Cobaleda 2018b), which pervaded the art of the first half of the 12th century. |

| 6 | For more information about the muqarnaṣ and its use during the Almoravid period and onwards, see Marcos Cobaleda and Pirot (2016). In this paper, a deep analysis of the methodology and application of the GIS for the study of the distribution of muqarnaṣ throughout the Mediterranean between 12th and 15th centuries has been presented. |

| 7 | The Masājid al-Janā’iz were a construction developed during the Almoravid period. They were oratories for funerals, where the rituals of prayer for the dead took place. For a more comprehensive analysis of this specific type of oratories, see Marcos Cobaleda (2021). |

| 8 | This method was developed by François Bouillé in 1977 (Bouillé 1977). |

| 9 | A deeper analysis of the CDM can be seen in Marcos Cobaleda (2023). In this work more details about the application of the GIS to the Art History research can be found. |

| 10 | The QGIS program was used as software for the different analyses in the ArtMedGIS Project. |

| 11 | This is the case, for example, for Aleppo, Damascus or Jerusalem. |

| 12 | Traditionally, these muqarnaṣ have been dated to the second half of the 11th century (Golvin 1965), however, A. Carrillo Calderero suggests that they would have been part of the reforms made in the Qal‘a of the Banū Ḥammād since 1090 and during the early 12th century (Carrillo Calderero 2009). If this hypothesis is correct, the muqarnaṣ of the Qal’a would be contemporary with the Almoravid examples. |

| 13 | No Almoravid muqarnaṣ ensemble has been preserved in Al-Andalus. The most ancient examples documented are the remains of a muqarnaṣ dome in the palace known as Dār al-Ṣughrà, in Murcia (Spain), built during the rule of Ibn Mardanīsh, in the second half of the 12th century (Marcos Cobaleda and Pirot 2016). |

| 14 | The intermediate step between the muqarnaṣ of the Qubbat al-Bārūdiyyīn and those of the Qarawiyyīn Mosque is the pierced dome of the maqṣūra of the Great Mosque of Tlemcen, in Algeria. The muqarnaṣ here are also present in the squinches and five small cupolas in the middle of the dome (Marcos Cobaleda 2015). |

| 15 | Much more data was collected during the project, which will be processed in the upcoming months, so this proportion will be significantly increased in the near future. |

| 16 | In Al-Andalus, there are examples of decorative pointed-horseshoe arches in the Great Mosque of Córdoba and the Ajafería of Saragossa (a Taifa palace built during the rule of the Banū Hūd in the last third of the 11th century). There is also an example of constructive pointed-horseshoe arches in the entrance of the alhanías from the northern portico of this palace; however, these seem to be the result of the reforms carried out in this palace during the first half of the 12th century. |

| 17 | The most ancient pointed-horseshoe arches in the eastern Mediterranean are the examples from the Bimāristān of Nūr al-Dīn, in Damascus, built in 1154 (Carrillo Calderero 2009), more than fifty years after the Almoravid pointed-horseshoe arches from Tlemcen and Algiers (Marcos Cobaleda 2021). |

| 18 | |

| 19 | The start date established for the chronological registers was the second half of the 11th century. |

| 20 | As explained before, the project ends at the beginning of the 16th century, when Mamluk rule came to an end. |

| 21 | It should not be forgotten that these results are provisional. In the specific case of the pointed-horseshoe arches, the percentages of religious architecture will be significantly increased once the implementation of the database is completed, based on the information gathered so far. |

| 22 | For a wider analysis of the relationship between the muqarnaṣ domes and vaults with Occasionalism in the Mediterranean basin, see Marcos Cobaleda and Pirot (2016). |

| 23 | Although it is widely considered that this is the most ancient example of Andalusi muqarnaṣ known to date, there is an hypothesis that assume that they were already used during the Taifa period, based on a source written by al-‘Udhrī (Al-‘Udhrī 1965), where the author described the palaces of the 11th century built by the king al-Mu’taṣim in Almeria. Some authors think that the muqarnaṣ domes were used in a reception room of these palaces, because the term muqarnas (ended by sīn س), written in the text, has been translated as “mocárabes” (Spanish translation for muqarnaṣ, ended by ṣād ص). Nevertheless, the term muqarnas (ended by sīn) is a different term from muqarnaṣ (ended by ṣād, and the correct term to refer to the artistic element analysed in this paper), and its correct translation is the one proposed by F. Corrientes: “in a grandstand” (Corrientes 1986), as it has been translated by M. Sánchez Martínez (1976). |

| 24 | The dates included in these examples are the specific date of construction of the muqarnaṣ ensembles, not the general date of construction of the buildings that contain them. |

| 25 | For a more comprehensive analysis of this issue, see Marcos Cobaleda (2021). |

References

- Al-‘Udhrī. 1965. Tarṣīʿ al-akhbār. Nuṣuṣ ʿan al-Andalus min Kitāb Tarṣīʿ al-akhbār wa-tanwīʿ al-āthār, wa-l-bustān fi gharāʾib al-buldān wa-l-masālik ilà jamīʿ al-mamālik. Edited by ʿA. al-ʿA. al-Ahwānī. Madrid: Instituto Egipcio de Estudios Islámicos. [Google Scholar]

- ArtMedGIS Project. 2016–2018. Available online: http://www.fcsh.unl.pt/artmedgis/ (accessed on 29 June 2022).

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo Máximo. 2005. El Islam: De Córdoba al mudéjar. Madrid: Sílex. [Google Scholar]

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo Máximo. 2012. A propósito del arte mudéjar: Una reflexión sobre el legado andalusí en la cultura española. In Mirando a Clío. El arte español espejo de su historia: Actas del XVIII Congreso del CEHA. Edited by María Dolores Barral Rivadulla, Enrique Fernández Castiñeiras, Begoña Fernández Rodríguez and Juan Manuel Monterroso Montero. Santiago de Compostela: Universidade de Santiago de Compostela, pp. 32–57. [Google Scholar]

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo Máximo. 2017. Los artífices del mudéjar: Maestros moros y moriscos. In XIII Simposio Internacional de Mudejarismo: Actas: Teruel, 4–5 de septiembre de 2014. Teruel: Instituto de Estudios Turolenses, Centro de Estudios Mudéjares, pp. 19–30. [Google Scholar]

- Borrás Gualis, Gonzalo Máximo. 2018. Génesis de la definición cultural del arte mudéjar: Los años cruciales, 1975–1984. Quintana: Revista de Estudios do Departamento de Historia da Arte 17: 15–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouillé, François. 1977. Un modèle universel de banque de données simultanément portable, répartie. Thèse d’État ès sciences (spécialité: Mathématiques, Mention: Informatique). Paris: Université Pierre et Marie Curie-Paris VI. [Google Scholar]

- Cabrera Lafuente, Ana. 2019. Textiles from the Museum of San Isidoro (León): New Evidence for Re-evaluating Their Chronology and Provenance. Medieval Encounters 25: 59–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2017a. Las artes en al-Andalus y Egipto. Contextos e intercambios. Madrid: La Ergástula. [Google Scholar]

- Calvo Capilla, Susana. 2007b. Viajes por el Mediterráneo entre los siglos VIII y XII. Tras los pasos de viajeros andalusíes, fatimíes y bizantinos. In Caminos de Bizancio. Edited by Miguel Cortés Arrese. Cuenca: Ediciones de la Universidad de Castilla-La Mancha, pp. 141–74. [Google Scholar]

- Carrillo Calderero, Alicia. 2009. Compendio de los Muqarnas: Génesis y Evolución. Córdoba: Servicio de publicaciones de la Universidad de. [Google Scholar]

- Ciski, Mateusz, Krzysztof Rząsa, and Marek Ogryzek. 2019. Use of GIS Tools in Sustainable Heritage Management—The Importance of Data Generalization in Spatial Modeling. Sustainability 11: 5616. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Corrientes, Federico. 1986. Diccionario árabe-español. Madrid: Instituto Hispano-Árabe de Cultura. [Google Scholar]

- De Felipe, Helena. 2014. Berber Leadership and Genealogical Legitimacy: The Almoravid Case. In Genealogy and Knowledge in Muslim Societies. Understanding the Past. Edited by Sarah Bowen Savant and Helena De Felipe. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press, pp. 55–70. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Jorge, María Elena. 2001. El arte mudéjar, expresión estética de una convivencia. Granada: Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Jorge, María Elena. 2007. Lecturas historiográficas sobre la convivencia y el multiculturalismo en el arte mudéjar. In 30 años de mudejarismo. Memoria y futuro (1975–2005): Actas [del] X Simposio Internacional de Mudejarismo. Teruel, 14–16 septiembre 2005. Teruel: Instituto de Estudios Turolenses, Centro de Estudios Mudéjares, pp. 735–46. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Jorge, María Elena. 2014. Arte y multiculturalidad en Granda en el siglo XVI. El papel de las imágenes en el periodo mudéjar y hasta la expulsión de los moriscos. In Arte y cultura en la Granada renacentista y barroca: La construcción de una imagen clasicista. Edited by José Policarpo Cruz Cabrera. Granada: Universidad de Granada, pp. 157–84. [Google Scholar]

- Díez Jorge, María Elena. 2016. Mujeres y arquitectura: Mudéjares y cristianas en la construcción, 2nd ed. Granada: Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- ESRI. 2013. The Language of Spatial Analysis. Redlands: ESRI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Fierro, Maribel. 2019. The Almohads: Mahdism and Philosophy. In al-Muwaḥḥidūn: El despertar del Califato almohade. Edited by Dolores Villalba Sola. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, pp. 23–41. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, Francine, ed. 2021. Mudejarismo and Moorish Revival in Europe. Cultural Negotiations and Artistic Translations in the Middle Ages and 19th-century Historicism. Leiden: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Giese, Francine, and Alberto León, eds. 2020. Diálogo artístico durante la Edad Media: Arte Islámico, Arte Mudéjar. Córdoba: Casa Árabe. [Google Scholar]

- Golvin, Lucien. 1965. Recherches archéologiques à la Qal’a des Banû Hammâd. Paris: Maisonneuve et Larose. [Google Scholar]

- Hoag, John D. 1975. Islamic Architecture. Milan: Electra Editrice. [Google Scholar]

- Ioannides, Marinos, Fabio Remondino, and Stefano Campana. 2013. GIS in Cultural Heritage. The International Journal of Heritage in the Digital Era 2: 4. [Google Scholar]

- Leonetti, Bulle Tuil. 2014. La “mosque des morts” almoravide de Fès. In Le Maroc médiéval. Un empire de l’Afrique à l’Espagne. Edited by Yannick Lintz, Claire Déléry and Bulle Tuil Leonetti. Paris: Musée du Louvre, pp. 204–11. [Google Scholar]

- López Guzmán, Rafael. 2006. El mudéjar de Granada y su proyección en América. In Arte mudéjar en Aragón, León, Castilla, Extremadura y Andalucía. Edited by María del Carmen Lacarra Ducay. Zaragoza: Diputación de Zaragoza, Institución “Fernando el Católico”, pp. 261–96. [Google Scholar]

- López Guzmán, Rafael. 2015. Arte Mudéjar—Arte Morisco: Consideraciones teóricas. In Lienzos del recuerdo: Estudios en homenaje a José Mª Martínez Frías. Edited by María Lucía Lahoz Gutiérrez and Manuel Pérez Hernández. Salamanca: Universidad de Salamanca, pp. 339–51. [Google Scholar]

- López Guzmán, Rafael. 2016. Arquitectura mudéjar: Del sincretismo medieval a las alternativas hispanoamericanas, 3rd ed. Madrid: Cátedra. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2015. Los almorávides: Arquitectura de un Imperio. Granada: Universidad de Granada. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2018a. Los almorávides, unificadores del Magreb y al-Andalus. In al-Murābiṭūn (los almorávides): Un Imperio islámico occidental. Estudios en memoria del Profesor Henri Terrasse. Edited by María Marcos Cobaleda. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, pp. 36–45. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2018b. En torno al arte y la arquitectura almorávides: Contribuciones y nuevas perspectivas. In al-Murābiṭūn (los almorávides): Un Imperio islámico occidental. Estudios en memoria del Profesor Henri Terrasse. Edited by María Marcos Cobaleda. Granada: Patronato de la Alhambra y Generalife, pp. 314–44. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María, ed. 2021. Artistic and Cultural Dialogues in the Late Medieval Mediterranean. Cham: Palgrave Macmillan. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María. 2023. Relaciones artísticas transculturales en el Mediterráneo tardomedieval. Un estudio a través de los Sistemas de Información Geográfica (SIG). In Granada y la memoria de su judería. Punto de debate. Edited by M. A. Espinosa Villegas. Granada: Universidad de Granada–Comares, in press. [Google Scholar]

- Marcos Cobaleda, María, and Françoise Pirot. 2016. Les muqarnas dans la Méditerranée médiévale depuis l’époque almoravide jusqu’à la fin du XVe siècle. Histoire et Mesure XXXI-2: 11–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, Andy. 2001. The Esri Guide to GIS Analysis, Volume 1: Geographic Patterns and Relationship. Redlands: ESRI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Andy. 2005. The Esri Guide to GIS Analysis, Volume 2: Spatial Measurements and Statistics. Redlands: ESRI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, Andy. 2012. The Esri Guide to GIS Analysis, Volume 3: Modeling Suitability, Movement, and Interaction. Redlands: ESRI Press. [Google Scholar]

- Pijoán, José, ed. 1949. Summa Artis. Historia general del Arte. Vol. XII. Arte islámico. Madrid: Espasa-Calpe. [Google Scholar]

- Pirot, Françoise. 2010. Du modèle conceptuel de données à la Géodatabase: Approche des risques sanitaires liés à l’eau à Cotonou (Bénin). In 1er Séminaire International Euro-méditerranéen sur « L’Aménagement du Territoire, la Gestion des Risques et la Sécurité Civile “Géomatique des Risques spatialisés, de la recherche à l’action territoriale” ». Batna: Université El Hadj Lakhdar. [Google Scholar]

- Pirot, Françoise. 2012. De la modélisation de l’information géographique à la création des données géo-spatiales. In Représenter la ville. Edited by Sandrine Lavaud and Burghart Schmidt. Bordeaux: Ansonius Éditions, pp. 309–43. [Google Scholar]

- Pirot, Françoise, and Thierry Saintgérard. 2005. La Géodatabase sous ArcGIS, des fondements conceptuels à l’implémentation logicielle. Géomatique Expert 41–42: 62–66. [Google Scholar]

- Revault, Jaques. 1984. Réflexions sur l’architecture domestique en Afrique du Nord et en Orient. In L’habitat traditionnel dans les pays musulmans autour de la Méditerranée. Rencontre d’Aix-en-Provence, 6–8 juin 1984. Cairo: Institut Français d’Archéologie Orientale, vol. 1, pp. 315–21. [Google Scholar]

- Rodríguez Peinado, Laura. 2017. Los textiles como objetos de lujo y de intercambio. In Las artes en al-Andalus y Egipto. Contextos e intercambios. Edited by Susana Calvo Capilla. Madrid: La Ergástula, pp. 187–205. [Google Scholar]

- Ruiz Souza, Juan Carlos. 2000. La cúpula de mocárabes y el Palacio de los Leones de la Alhambra. Anuario del Departamento de Historia y Teoría del Arte (UAM) 2: 9–24. [Google Scholar]

- Sánchez Martínez, Manuel. 1976. La cora de Ilbira (Granada y Almería) en los siglos X y XI, según al-Udri (1003–1085). Cuadernos de Historia del Islam 7: 5–82. [Google Scholar]

- Tabbaa, Yasser. 2001. The Transformation of Islamic Art during the Sunni Revival. London and New York: The University of Washington Press. [Google Scholar]

- Terrasse, Henri. 1968. La mosquée al-Qaraouiyin à Fès. Paris: Librairie C. Klincksieck. [Google Scholar]

- Tolaba, Ana Carolina, María Laura Caliusco, and María Rosa Galli. 2013. Meta-ontología Geoespacial: Ontología para Representar la Semántica del Dominio Geoespacial. In Anales de CoNaIISI 2013. Córdoba: Universidad Tecnológica Nacional, pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Yarza Luaces, Joaquín, José Carlos Valle Pérez, Mª Jesús Gómez Bárcena, Francesca Español Bertrán, Germán Navarro Espinach, Amalia Descalzo Lorenzo, and Concha Herrero Carretero, eds. 2005. Vestiduras ricas. El monasterio de Las Huelgas y su época 1170–1340. Madrid: Patrimonio Nacional. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Marcos Cobaleda, M. Artistic Transfers from Islamic to Christian Art: A Study with Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Histories 2022, 2, 439-456. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2040031

Marcos Cobaleda M. Artistic Transfers from Islamic to Christian Art: A Study with Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Histories. 2022; 2(4):439-456. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2040031

Chicago/Turabian StyleMarcos Cobaleda, María. 2022. "Artistic Transfers from Islamic to Christian Art: A Study with Geographic Information Systems (GIS)" Histories 2, no. 4: 439-456. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2040031

APA StyleMarcos Cobaleda, M. (2022). Artistic Transfers from Islamic to Christian Art: A Study with Geographic Information Systems (GIS). Histories, 2(4), 439-456. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2040031