1. Introduction

After the British founded Singapore in 1819, a large number of immigrants from the southeast coast of China came to Singapore to survive because of poverty. The Chinese immigrants’ living environment in their homeland was strongly regional, and people in the same region shared the same dialect, customs, and culture, and had a strong ancestral identity. When they came to Singapore, they were quick to replicate their living environment in China by using dialect groups as the basis for division. Therefore, the early Chinese community in Singapore was divided by dialect communities, that is, the dialect group power society 帮权社会. With the increase in immigration, the early Chinese society in Singapore manifested itself as a conflict and cooperation among the five major dialect groups.

1As we know, death was a matter of great importance to the Chinese, and that is the same for Chinese immigrants. As the number of immigrants increased, so did the number of deaths. The friends or relatives of the deceased will then help them with the burial. As the number of deaths increased, cemetery hills emerged. In the 19th century, Chinese cemetery hills were established by the leaders of each dialect group for the burial of the lower and middle classes of the Chinese community, which had a strong dialect group aspect 帮群色彩 behind them. These cemetery hills were not only a place for them to bury their dead, but also a place to unite the dialect community. Therefore, it is one of the important perspectives to understand the development of the Chinese community in Singapore by understanding the development of the cemetery hills for dialect groups and the changing power structure of the dialect group behind. In addition, the present-day Singaporean society is still predominantly Chinese, so it will be important to understand the changes in the Chinese community for the cemetery hills to help and enlighten the historical lineage of Singapore.

In recent years, some scholars have also realized the importance of understanding the situation of the Chinese community from the cemetery hills. For example, in the course of the development of the Chinese cemetery hills in the 19th century, Lim How Seng 林孝胜 (

Lim 1975) divided them into two levels, one is the Hokkien cemetery hills, the other is the “United Front” 联合阵线 cemetery hills mainly formed by Hakka and Cantonese, followed by the Teochew and Hainan dialect groups. After Lim, Zeng Ling 曾玲 (

Zeng 2005,

2007) made a meticulous compendium of the history of Fuk Tak Chi Lu Ye Ting 福德祠绿野亭, which is an important cemetery hill in terms of the United Front. Moreover, she emphasized their roles in Chinese identity and homeland identification on the basis of the “two-level confrontation 两级对峙”. While some scholars such as Li Yong 李勇 (

Li 2008), Choi Chi-cheung 蔡志祥 (

Choi 2016), Hue Guan Thye许源泰 (

Hue et al. 2019), and Zhong Jianhua 钟健华 (

Zhong 2020) have emerged since then to address the issue.

2Most of the studies on the cemetery hills in Singapore focus on specific dialect groups, which only reflect the relationship and development between individual dialect groups and the cemetery hills but do not challenge the “United Front” view and take into account the development of the Chinese community as a whole. Moreover, these scholars have focused on the situation of the cemetery hills of particular dialect groups, and less on their overall development and its reflection on the communities of the various dialect groups. In contrast, many studies on the history of land acquisition and relocation of the Chinese cemetery hills in Singapore in the 20th century have been conducted from the perspective of the Chinese community, but most of these studies were centered on discussions of government policies and the Chinese community’s protests and compromises with them. Their studies also involve descriptions of the situation on the cemetery hills of various dialect groups, but mostly highlight their response to the expropriation policy and lacked an understanding of their autonomy under the government (

Yeoh 1991, pp. 282–310;

2003, pp. 282–311;

Yeoh and Tan 1995, pp. 184–201;

Freedman 1960;

Freedman and Topley 1961, pp. 3–23). These two types of Singaporean cemetery hill research always have their own emphatic perspective. Although some of these essays did not directly point to the relations between Chinese cemetery hills, Chinese dialect groups, and the government, they provide us an overall view in the development history of the Overseas Chinese, including that of Singapore. The perspective adopted by these articles is either from a British colonial view, or two-level confrontation perspective of Chinese society (

Heng 2020;

Kong and Yeoh 2003;

PuruShotam 1998;

Yen 1991,

2017).

In this paper, we will draw on the strengths of the above literature to sort out the process of Cemetery Hill from its establishment to its eventual home in the historical context of Singapore. In turn, we will look at the communication and exchanges between the small communities under the five major dialect groups to understand the development and changes in the structure of dialect group politics in Chinese society as a whole. This is also a response to the ‘two-level confrontation’ of dialect group power in 19th-century Chinese society. The autonomy of Chinese society in the 20th century will also be analyzed with regard to its response to government policy.

This study uses a historical anthropological approach. Through field research, inscriptions, and folk Chinese newspapers, combined with official documents, the development of cemetery hills in each dialect group is understood from a folk perspective, reflecting the development and changes of the Chinese community. Due to the lack of data, previous scholars were unable to obtain comprehensive information about the mounds of each dialect group, and naturally, they were unable to understand the development and connection of each dialect group from the perspective of the Chinese community as a whole. However, since 2015, a research team from the Department of Chinese at the National University of Singapore (NUS) has been developing the Singapore Historical Geographic Information System (SHGIS) to collect and collate data on the Chinese cemetery hills and has made more new discoveries on the cemeteries through the field research. (

Yan et al. 2020, pp. 1–23). As part of the research team, we were able to gain a better understanding of Singapore’s cemetery hills based on the fieldwork. In particular, it allows us to microscopically identify the early migratory situation in Singapore and the strong links between the different dialect groups and discovers the situation and development of the smaller communities based on locality or blood identities under the Chinese dialect groups, the discussions which are ignored by the previous scholars who generally followed the concept of “two-level confrontation” to interpret the situation in 19th century Singapore Chinese society.

On this basis, the research team has re-organized the historical information on the cemetery hills of different dialect groups in the past three years, combining the results of their own fieldwork and references to different documents in English and Chinese, and has made relevant revisions and additions to the Chinese cemetery hill tables, as shown in

Table 1,

Table 2,

Table 3 and

Table 4 below. These tables record the visual information of the opening date, geographical location, closure date, and location of the burial of Chinese cemetery hills in Singapore, which not only facilitates the research of cemetery hills by later scholars but also allows us to compare and analyze the similarities and differences of the development of each dialect group of Chinese cemeteries hills from a holistic perspective, and to gain an understanding of their autonomy under government rule.

2. New Discovery of the Tombs at Heng San Ting 恒山亭 (1820–1850)

In the early years, the Chinese society in Singapore was categorized according to the dialect groups of the migrants’ hometowns in China, and they had their own leaders who operated individually to form dialect group politics 帮权政治

3. The immigrants from the Hokkien dialect group were the first among the five major dialect groups to arrive in Singapore. It gradually developed into the largest group in Singapore, and even today still has a certain voice in the Chinese community. However, Chinese communities in the 19th century were not only divided by dialect groups, but could also be divided into smaller locality communities 地缘社群 based on the same county of their homeland under the larger dialect community (

Crissman 1967, p. 193;

Yen 1991, pp. 33–40). For example, the Hokkien community in Singapore could be subdivided into smaller locality groups such as Zhangzhou 漳州, Quanzhou 泉州, Yongchun 永春, Fuzhou 福州, and Putian 莆田 based on their different geographical location in Fujian, China. In terms of the internal structure of the Hokkien dialect group, the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou groups formed the largest number in the community. After the opening port of Singapore, the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou families from Malacca such as the Chua, Tan, See and Khoo surname clans were the earliest Chinese to immigrate there (

Dennerline 2022, pp. 8–10). They were long settled down in Malacca and called “Peranakan Chinese” since their ancestors married native women and formed the local Chinese community there (

Lee 2013, pp. 406–8). These families came to Singapore and became the most dominant group in the Hokkien community. An example is the 1830 establishment of Heng San Ting, the earliest cemetery hills and also the highest institution of the Hokkien community at the time, was mainly supported by the merchants of Zhangzhou and Quanzhou groups (

Jao 1970, pp. 23–24;

Lee 2013, p. 408).

The directors like See Hoot Kee 薛佛记, and Tan Che Sang 陈送 were originated from the Zhangzhou group too. (

Jao 1970, pp. 23–24) Hence, it could be seen that the Singapore Hokkien community was dominated by these two groups in the early stage, many scholars believed that Heng San Ting only buried the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou people (

Hue et al. 2019;

Lim 1975;

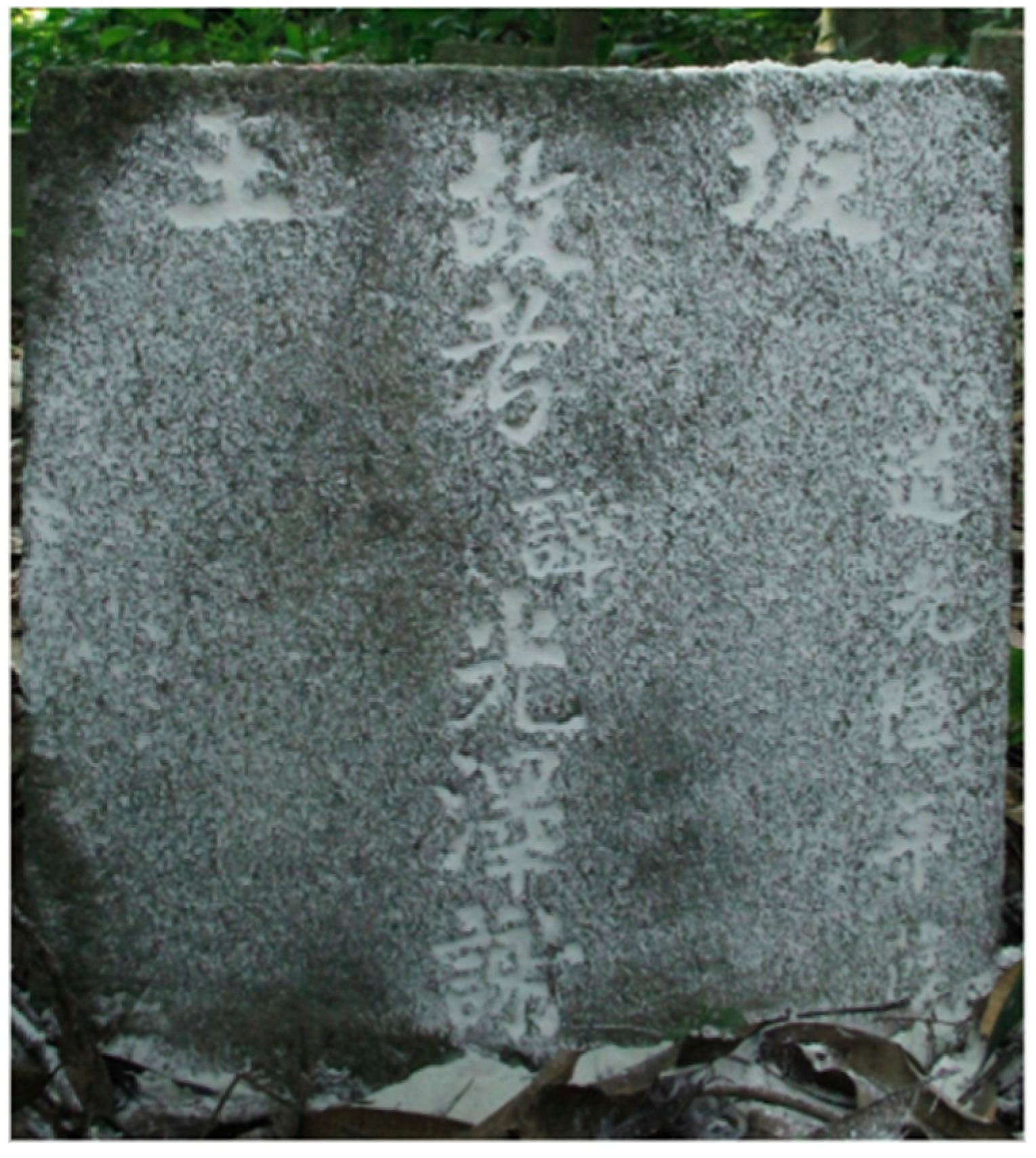

Kua 2007). However, this opinion could be changed after some new tombstones were found through the research fieldwork carried out by our research team in recent years in Bukit Brown. However, the research team collected information on 459 gravestones from the New Heng San Ting area in the existing cemetery hill Bukit Brown, 259 tombstones were found to have been erected during the Daoguang period of Qing dynasty, China (1821–1850). Between 1880s and the 1920s, a large area of the land of Heng San Ting was expropriated by the government (See below content), a few hundreds of the earliest gravestone stones were relocated to the new Heng San Ting cemetery, which is now located at the Bukit Brown Cemetery Hill. Our research team was the first in recent years to discover these more than 400 gravestones in the area, which is one of the earliest Chinese grave clusters in Singapore. Hence, this is an important reference for us to understand the internal structure of early Hokkien immigrants. This is because the tombstones contain important information such as surname, year of death and place of origin, which can be regarded as the identity card of the dead. Here, we find the tomb of Xie Guangze 谢光泽 (

Figure 1) buried in 1826, which is not only the earliest known Chinese tomb in Singapore, but also indicates that Heng San Ting was opened earlier than what is perceived, as some scholars (

Leon 1958, p. 64;

Zhang 1975, p. 41) generally believe that Heng San Ting was established in 1828.

Among this group of tombstones, the team found that some were large in thickness and size, while others were very thin and simple-looking. These came from the same countryside of south Fujian, indicating that both wealthy families and poor laborers migrated south to Singapore at the same time during the Daoguang period. Among the surnames and numbers of the deceased, 40 of them belong to the Chua 蔡 surname group, of which 32 were all from the “Chua clan of “Xie Cang 谢仓”. This implies that a large group of people from the Chua clan migrated from a single village during the earliest wave of Chinese migration from Fujian to Singapore. They belonged to the clan of the Malacca Chinese Kapitan 甲必丹 Chua Su Cheong 蔡士章. Today, the Chua Ancestral Hall in Xie Cang 谢仓, Zhangzhou, Fujian Province, a stone tablet of Chua Su Cheong’s donation to repair the ancestral hall in 1801 is still preserved, and Chua Su Cheong’s memorial tablet is also placed in the hall (

Zheng and Dean 2003, p. 308). Nearby, the Haicheng City God Temple 海澄城隍庙 was rebuilt in the Republic of China (1916), donations were recorded from the Singapore Prime Minister Chua Sun Yee 蔡新义of the Singaporean Xie Cang Chua clan. (

Lim 1925, pp. 104–5) When combined with the newly discovered tomb of the Xie Cang Chua clan at the Heng San Ting, the Chua clan, a prestigious family from Malacca, had already migrated to Singapore in large numbers during the Daoguang period.

More importantly, the other groups with a larger number of surnames were: Tan 陈 (32), Yeoh 杨 (24), Lee 李 (19), Lim 林 (18), Wong 王 (9), Ng 黄 (8), and Giam 严 (4). Some of the tombstones are not recorded with the original hometown but are presented with ancestral hall names representing the surname, reflecting the important cohesive role that blood ties played in the early history of Chinese immigrants in Singapore. Looking back at the persuasive contribution list inscriptions erected at the time of the establishment of Heng San Ting in this period (1830 in the Daoguang decade) by See Hoot Kee, the six major surnames of Tan 陈, Chua 蔡, Zeng 曾, Lim 林, Yeoh 杨, and Wong 黄 contributed more than half of the total number of donors (

Jao 1970, pp. 23–24). Except for the Zeng surname people, the deceased of the other five surnames are represented in the newly discovered tombs.

The clansmen of these surnames could be considered not only as of the first group of immigrants to Singapore but also as important families among the Hokkien who went to Nanyang 南洋 and formed a large social network in the Malay Peninsula. For example, as early as 1800, when the Penang Chinese community build the Penang Kong Hock Kong Kwan Yim Teng 槟榔屿广福宫观音亭, more than half of the donors were from the nine surnames, including the six surnames mentioned above (

Franke and Chen 1985, pp. 530–31). In 1831, of the Bukit Cina gold contribution wooden plaques “三宝山墓地捐金木牌” in Malacca, the six surnames donated more than 40% (

Jao 1970, pp. 23–24). Although it is impossible to conclude that people with the same surname as in the six surnames belonged to the same locality or clan, the Hokkien group that went overseas in the early days had the habit of immigrating to and living in clans by kinship mode and carrying out social activities by family blood organization (

Teoh 2005, pp. 43–44). Therefore, there should be no shortage of people with a certain number of the same clan among the six surnames.

Scholars generally agree that the Malacca Peranakan dominated the Hokkien group in Singapore. They focus mainly on the development of the power of these Chinese leaders in Malacca and Singapore, but rarely highlight the immigration of the clan or families who had a great influence on the formation of Hokkien community in Singapore (

Wong 1963, pp. 31–32;

Lim 1975, pp. 6–20;

Dennerline 2022, pp. 8–10;

Lee 2013, pp. 406–8). However, from the new graves excavated at Heng San Ting, it is possible to understand that these large families who were already active in Southeast Asia, particularly in Malacca, such as the Chua surname clan, were connected to other Chinese clans or families in the region, forming a large network of family power to protect their interests. The strong economic and social influence of the clans also contributed to their continued dominance of the local Hokkien dialect group. For example, See Hoot Kee 薛佛记 and Tan Tock Seng 陈笃生 families continued to monopolize the dominance of Heng San Ting and Thian Hock Keng 天福宫, both of which can be regarded as the most important institutions of the Hokkien community (

Hue et al. 2019, p. 15).

In the Hokkien dialect group, they also formed their surname communities based on their clan or family. Some of the powerful clans could even establish their own clan cemetery hills, temples or clan associations to expand their social influence in the Chinese community (

Yen 1991, pp. 67–70). This set the stage for the creation of surname organization burial hills by the surname communities of the Hokkien dialect group in the mid to late 19th century (See below content). However, these powerful Hokkien clans did not only originate from the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou groups, for after the 1850s, the Malacca Peranakan Tan Kim Seng, of Yongchun, Fujian, also rose in power, even replacing the position of late Tan Tock Seng as the top leader of the Hokkien community (

Lim 1975, pp. 17–18;

Wong 1963, p. 32). From the growing career of Tan Kim Seng after 1850s mentioned above, it indicates that the possibility of Tan Kim Seng family or his clan had already gained some influence of the Hokkien community in Singapore or even Malacca from an early period that we have overlooked previously. This claim is not unfounded as this new discovery was seen in the newly excavated tombs of Heng San Ting.

Apart from the immigration of the Hokkien dialect group from Malacca to Singapore, the most significant aspect of the tombs is that they have turned the traditional knowledge of Hokkien immigrants overseas upside down. The research team collated the places of origin of the deceased engraved on the inscriptions of these 459 tombs into 133 counties, cities, townships and villages from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in Fujian Province, China, such as Haicheng 海澄, Xiamen 厦门, Nanyang 南阳, Longjin 龙津, Xiecang 谢仓, Pengshan 彭山, Zhengdian 郑店, Tongan 同安 and Changtai 长泰. At least 81 of them are from Zhangzhou 漳州, 65 from Quanzhou 泉州, 45 from Xiamen 厦门, 32 from Fuzhou 福州, and 20 from Putian 莆田, while the original hometown of the rest of the gravestones is unknown. Among these places, up to 80% of the deceased originated from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou, but it shows that 20% of Hokkien immigrants came from other places.Although the information is not yet comprehensive, the tombstone records reveal an important finding that challenges the long-held belief that the earliest Hokkien people immigrants came from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou in southern China, while the Anxi people 安溪人 from the mountainous areas and the Fuzhou 福州人 and Putian 莆田人 people from eastern Fujian arrived in Nanyang at a later period. The previous studies on the history of Chinese migration generally agree that the earliest overseas migrants came from the coastal areas of Fujian such as Zhangzhou, Xiamen, Quanzhou and other southern Fujian areas 闽南地区, while the inhabitants of other areas such as Anxi and Yongchun were inland, and the lack of transport and ports contributed to their relatively late immigration period compared to the immigrants from coastal areas (

Lee 2013, p. 406;

Yen 2017, pp. 129–34;

Dennerline 2022, p. 10). However, the newly unearthed graves at Heng San Ting disprove this claim and prove that many immigrants from the interior of Fujian or areas outside southern Fujian already migrated to Singapore in the early19th century.

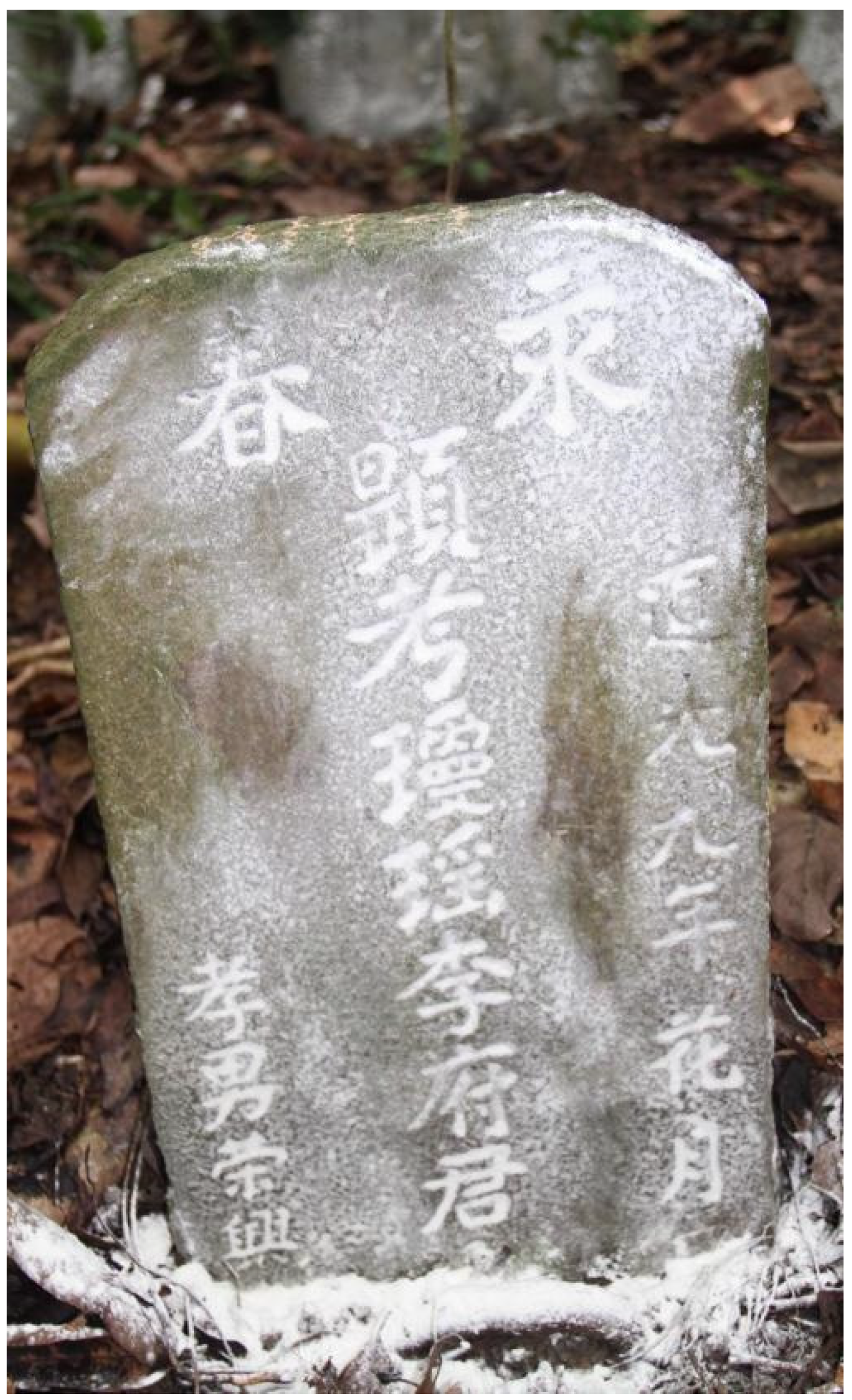

Among the newly excavated Qing dynasty graves at Heng San Ting, the grave of “Li Qiongyao 李琼瑶” (

Figure 2) who was originally from Yongchun 永春 and died in 1829, can be considered as one of the earliest Chinese cemeteries in Singapore. The discovery of this grave indicates that Yongchun people migrated to Singapore as early as 1829, only ten years after the founding of Singapore in 1819. This also suggests that the Yongchun people were one of the earliest Hokkien groups to migrate to Singapore.

4 The migration of Yongchun people to Singapore is also supported by the genealogies cited by

Du (

2017, p. 6), which record a total of 23 Nan’an 南安 (inland county of southern Fujian) and Yongchun people came to Singapore during the Qianlong 乾隆 (1736–1796) and Jiaqing 嘉庆 (1796–1820) periods, and they were buried in Signapore. According to the

Quanzhou Genealogy of Overseas Chinese Historical Sources and Research 泉州谱牒华侨史料与研究, Mr. Wong, a migrant from Yongchun had already travelled to Singapore before 1770. The inscription on the tablet reads, “Zesheng Gong, the second son of Yirui Gong, was born in 1705 and died in 1770, who lived in Singapore. 则盛公, 懿瑞公次子, 生康熙乙酉年 (1705年), 卒乾隆庚寅年 (1770年), 住新加坡” (

Zhuang and Zheng 1998, p. 228). Since the year of Li Qiongyao’s death is close to the Qian-Jia period乾嘉年间 (1736–1820), it can be inferred that there were already a substantial number of Yongchun people who came to Singapore at that time, no later than the Zhangzhou and Quanzhou people on the coast.

Hence, it can be concluded that Yongchun people travelled to Singapore even before its founding by the British. This may be closely connected to the appointment of Tan Kim Seng as Justice of Peace by the British colonial government, a position only offered to the top leaders of the Chinese community according to the British colonial government (

Wong 1963, pp. 27–31). A Peranakan from Malacca with his ancestral origin in Yongchun, Tan Kim Seng’s rise to power indicated that the Yongchun migrants were a significant group in Malacca and Singapore and had developed a certain amount of power by the early 19th century. The case of Tan Kim Seng is an example that his family or clan was one of the earliest immigrants who moved from Yongchun to Nanyang and gained their influence in Singapore and Malacca. In addition, the presence of migrants from Yongchun, Anxi, Fuzhou and Putian discovered in the Qing tombstones of Heng San Ting disproves the claim that Heng San Ting was initially a communal cemetery for Zhangzhou and Quanzhou immigrants as argued in previous studies (

Lim 1975, pp. 6–7;

Hue et al. 2019, p. 24). It is now confirmed that, in addition to the immigrants from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou, there were also many migrants from other areas such as central and eastern Fujian regions who had migrated to Nanyang and were buried in Heng San Ting.

In 1846, See Hoot Kee 薛佛记 made an announcement to build Si Jiao pavilion 四角亭, a new cemetery hill at Heng San Ting, stressed that “in the future all the people from Fujian can be buried here if they encountered a mishap” “厥后凡系福建人,倘有不测,可从此而葬焉” (

Jao 1970, p. 28). The new Chinese cemetery has no “Zhangzhou and Quanzhou” division. The excavation of the new graves at Heng San Ting proves that the early Hokkien who migrated to Singapore and were buried at Heng San Ting came from different locality communities, but they were eventually united in the Heng San Ting as they belonged to the Hokkien dialect group. Although Heng San Ting was led by the See Hoot Kee family from Zhangzhou, it had always existed as a cemetery hill for all migrants from Fujian, accommodating the locality communities including those from Central and Eastern Fujian. The excavation of the Heng San Ting tombs also goes further towards explaining the reason why the Melaka Peranakan dominated the Hokkien dialect group in Singapore. These families migrated to Singaporean society and continued to expand their influence in the Hokkien community through blood ties.

Seah Eu Chin 佘有进, the leader of the Teochew dialect group, made a census of the population of the various Chinese dialect groups in Singapore in 1848, specifically singling out the 1000 Hokkien born in Malacca from the overall Hokkien population, indicating the importance of this group in the local Chinese community (

Logan 1848, p. 290). The fact that the Hokkien were always at the forefront of power politics had to do with the power of the Malacca Hokkien family. We discover that the Hokkien dialect group in Singapore is closely related to the Hokkien immigrants in Malacca. However, these families were not necessarily from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou as traditionally perceived by scholars. Tan Kim Seng, a Peranakan leader from Malacca, who later gained the leadership of the Hokkien dialect group in Singapore, was of Yongchun origin. In addition, although the Hokkien community was dominated by people from Zhangzhou and Quanzhou, we should not ignore other geo-community groups such as those from Putian and Fuzhou. Although the latter were not from Southern Fujian, many of them were buried in Heng San Ting. The structure of Hokkien dialect group in Singapore was more diverse and complex in reality.

3. The Creation of Singapore Cemetery Hills of Chinese Dialect Groups in the Early 19th Century (1820–1850)

In the early days of Singapore’s founding, the British colonial government was unable to implement a strict and comprehensive rule over the Chinese community in Singapore due to the administration of Singapore, Penang and Malacca (

Tan 2016, p. 30). Hence, they adopted the method of Chinese autonomy, the Chinese community could be divided into different dialect groups. Apart from the Hokkien dialect group, other dialect groups such as the Cantonese, Hakka and Teochew also migrated to Singapore at an early stage. They formed their own communities based on dialect and local identity from hometown China, and like the Hokkien, they established their own dialect group cemetery hills soon after the opening of Singapore. The creation and development of these cemeteries not only represented a place for the dead to be buried, but also reflected the division, confrontation, and liaison between the different dialect groups, which were always driving the development and changes of the Chinese community in Singapore.

As historical data show, the British government appointed Tan Tock Seng 陈笃生 and Tan Kim Seng 陈金声 as Justices of Peace, who were both of the Hokkien dialect group in Malacca and reflects the dominance of the Hokkien dialect group in Chinese society at the beginning of Singapore’s founding (

Wong 1963, p. 6). At the same time, the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups in Singapore were smaller in numbers, and the population figures from Seah Eu Chin showed that in 1848, the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups had only 6000 and 4000 people respectively, the sum of which only equalled the total number of Hokkien. The Cantonese and Hakka comprised mostly of working-class labourers, unlike the Hokkien group which had a larger merchant class (

Logan 1848, p. 290). The two dialect groups, because of their small populations and lack of economic power, chose to run the cemetery hills—Qing Shan Ting 青山亭 and Lu Ye Ting 绿野亭—together at the outset (

Zeng 2005, pp. 9–10). The two dialect groups were also distinguished into seven locality communities 广客七属 based on their administrative divisions in China. Among them, the Guangfu 广府 and Zhaoqing 肇庆 locality groups from the Cantonese group formed a larger community with the Huizhou 惠州 from Hakka group, which is better known as the Kwong Wai Shiu 广惠肇 community; the three Hakka locality group Fengshun 丰顺, Yongding 永定 and Tai Po 大埔, which came from eastern Guangdong and western Fujian, formed the Fung Wing Tai 丰永大 community; and the Jiaying 嘉应 locality group remained as one community (

Tao 1963, pp. 1–6). To sum up, these seven groups (Guangfu, Huizhou, Zhaoqing, Fengshun, Yongding, Dabu, and the Jiaying) united into three major communities (Kwong Wai Shiu, Fung Wing Tai and Jiaying) due to their respective geographical origins, and they collaborated to form a larger community which eventually led to the creation and management of the cemetery hills for Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups (

Tao 1963, pp. 1–6;

Zeng 2005, pp. 15–16). Within the Chinese community, it is common for small locality communities to come together to form a larger community to increase their strength and influence (

Crissman 1967, p. 193). It shows the connection of these locality groups to the highest institution in the form of dialect groups, as well as their retention of independent development in their own locality communities (

Lim 1975, p. 20).

When Lu Ye Ting was founded in 1840, an inscription on a stone tablet clearly stated that the cemetery was jointly run by the seven groups (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 81). However, Lu Ye Ting was not the first cemetery hill jointly operated by the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. As can be seen from the

Inscriptions Record for Rebuilding the Cemetery hill in Yongding County of Guangdong Province and “广东省永定县重修冢山碑记 in 1840, “my people from Guangzhou, Huizhou, Zhaoqing, Jiaying, Tai Po, Fengshun, Yongding had previously united together to run a cemetery hill. However, for years, there were too many overcrowded graves, with coffins stacking over other coffins already buried inside, which is shocking and saddening… 我广、惠、肇、嘉应州、大埔、丰顺、永定等庶,昔年亦有公司之山,奈历年多麟叠叠,不惟坟墓相连,抑且棺上加棺,触目固皆伤心之处……” (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 81) they had already been operating cemetery hills together before the Lu Ye Ting opened. According to the testimony, the cemetery hill before that was the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery.

From the available historical data, it is impossible to determine the year of establishment of Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery. However, we can presume that it is the earliest cemetery hill of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. According to Brenda Yeoh’s research, the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery covers an area of about 20 acres, (

Yeoh 1996, p. 285) or about 1.2 million square meters. If we roughly calculate a coffin or tomb at six square meters, it is estimated that about 200,000 Cantonese and Hakka ancestors were buried in Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery. In a span of 30 to 40 years, 20 acres of cemeteries were “graves joined together, coffins laid upon coffins 坟墓相连,棺上加棺”, which shows that there were already a certain number of Cantonese immigrants coming south at the beginning of Singapore. This is not only the exception in Singapore, but also in Penang and Malacca, where the two dialect groups were the minority in these places. These groups had been operating the cemetery hills together for a long time.

The seven groups of Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups who chose to unite together to form the cemetery hills because of their limits in size and economic power. However, Gongzhu Tao 陶公铸 (

Tao 1963, p. 1) think the seven communities of Cantonese and Hakka in Singapore had formed a partnership to build the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi 海唇福德祠 in 1824, as the top management organization for Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups before running Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery and Lu Ye Ting together. Haichun Fuk Tak Chi was the only temple built by Kwong Wai Shiu 广惠肇, the Hakka dialect group’s Jia Ying 嘉应 and Fung Wing Tai 丰永大 groups joined the temple only when it was restored in 1854 (

Government Printing Office 1894, pp. 24–16;

Zeng 2005, p. 4). The latter two Hakka dialect groups used the Wang Hoi Fook Tong temple 望海福德祠 as their dialect group’s top management organization (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 226). These proves that these three groups (Kwong Wai Shiu, Jia Ying, Fung Wing Tai) did not actually belong to the same community, they run different temples and formed their own communities, but they were connected when they operated the cemetery hills. Even though Huizhou 惠州 belonged to the Hakka dialect group, it did not hold the leadership of the Wang Hoi Fook Tong temple, suggesting that the division of the community at that time could not be necessary based solely on the attributes of the dialect group but also on the smaller locality community they formed. Although Huizhou was part of the Hakka dialect group, it had closer ties with the Cantonese people of nearer locality in China, namely Guangfu and Zhaoqing, and thus they formed their own community, Kwong Wai Shiu. It could suggest that the cemetery hill played an important role in the integration of seven groups of Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups.

With regard to the Singaporean Cantonese and Hakka diaelect groups who jointly operated Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery and Lu Ye Ting,

Lim (

1975, p. 25) mentioned that the cooperation of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups was the formation of the “United Front 联合阵线” to protect their rights and interests in order to counteract the powerful forces of the Hokkien dialect group.

Lim (

1975, p. 25) also emphasized that the early headquarters of the United Front was located in Lu Ye Ting, the cemetery hill they jointly operated. By 1854, the headquarters of the United Front was officially moved from Lu Ye Ting to Haichun Fuk Tak Chi, and the seven communities of Cantonese and Hakka officially jointly operated the temple, at the same time, the Teochew and Hainan dialect groups joined also the United Front in this year, since they also participated in the donation to the temple (

Lim 1975, p. 25;

Tao 1963, pp. 15–20). Scholars generally agree with Lim’s opinion, this is because there are no records of other dialect groups donating plaques or couplets to the Hokkien temples in Singapore, which is sufficient to show that the Hokkien dialect group rarely interacted with other dialect groups and even conflicted with them. The same situation happened in Penang and Malacca in the 19th century where the Hokkien dialect group was dominant and the other four dialect groups formed a United Front as a counteractive measure. (

Chong 2007, pp. 134–37)

While there is some truth in this statement, it does not necessarily reflect the overall situation of the Chinese community in the 19th century. In addition to the donations from Teochew and Hainanese immigrants, the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi temple also received donations from the Hokkien leader, Cheang Hong Lim, in 1869 and 1870 (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 68). Then, the inscriptions on the temple make it clear that, besides the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, devotees from Hokkien, Teochew and Hainan communities would also visit and worship the deities in the temple (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 69).

Dean and Hue (

2017, pp. 238–41) also found plaques donated to the temple by devotees of the Hokkien dialect group to the Wang Hoi Fook Tong temple, a Hakka temple dominated by the Jiaying and Fung Wing Tai communities. This evidence suggests that beyond the leadership of the different dialect groups, the grass-roots society of the Hokkien community interacted with the temples of other dialect groups, and did not necessarily have a “two-level confrontation”.

Moreover, the situation of Teochew and Hainan dialect groups operating their own cemeteries from the beginning does not suggest that these two communities leaned towards a “United Front” formed by the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. Teochew immigrants came mainly from the Chaozhou 潮州 and Shantou 汕头 regions of eastern Guangdong Province, and like other dialect groups, the Teochew dialect group can be subdivided into smaller locality communities based on the geography of their homeland, with the Haiyang 海阳 group from Chaozhou county and the Chenghai 澄海 group from Shantou being the dominant in the dialect group (

Yen 2017, p. 46). The Teochew community had strong links with the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, and in the early nineteenth century there are many records of plaques and couplets donated by the Cantonese and Hakka communities to the Wak Hai Cheng Bio Temple 粤海清庙, the highest headquarters of the Teochew community, founded by the Haiyang and Chenghai groups (

Dean and Hue 2017, pp. 2–34). However, the Teochew did not choose to form the cemeteries hill jointly with the Cantonese and Hakka communities. For example, the clan of Seah Eu Chin, who was originally from Chenghai, established the Ngee Ann Kongsi 义安公司 in 1845 to compete with Wak Hai Cheng Bio Temple to become the highest institution of the Teochew community (

Yen 2017, pp. 79–93). Up to the year 1930, the Seah family dominated and monopolized the leadership of the Teochew dialect group for nearly 100 years, and the first cemetery hill of the community, Tai Shan Ting 泰山亭 was set up by Ngee Ann Kongsi in 1845 (

Yen 2017, pp. 79–93). The reason why the Teochew community chose to run their cemetery alone was that their population was the largest in the dialect groups at that time, reaching around 20,000 in 1848 (

Logan 1848, p. 290). As a result, Teochew people had enough economic strength to establish a cemetery hill themselves. However, as most of them were engaged in pepper and gambier cultivation, the planters were economically weak and lacked influence in the community (

Logan 1848, p. 290). This leads to the historical development of the Teochew dialect group being seen as less powerful than the Hokkien dialect group, and that dominated the former dialect group was dominated by a single locality group, the Seah Eu Chin family of Chenghai group, for a hundred years (

Yen 2017, p. 51).

Although the Teochew dialect group ran its own cemetery hill, they interacted with the Hainan and Hokkien dialect groups in terms of leadership and the grass root society. Apart from the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups mentioned above, there were also plaques donated by the Teochew dialect group to the temple of the Hainan people, Kheng Chiu Tin Hou Kong 琼州天后宫, and also plaques to the Wak Hai Cheng Bio from the Hainan people (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 13). Although the Hokkien dialect group did not donate plaques to the Teochew temples, some of the leaders and people from the two dialect groups cooperated in economic activities, which is not mentioned by previous scholars. For example, Seah Eu Chin, the leader of the Teochew dialect group, had a close relationship with the Hokkien merchant Yeo Kim Swee, the former inherited the latter’s land and property after his death (

Song 1993, p. 62). In addition, Seah Eu Chin’s brother-in-law, Tan Seng Poh 陈成宝 formed the “Great Syndicate” in the 1860s in partnership with the Hokkien opium revenue farmer, Cheang Hong Lim, when they monopolized the opium and liquor revenue farm in Singapore for ten years (

Trocki 1993a, pp. 252–53). The opium and liquor revenue farm in Singapore was long dominated by Cheang Hong Lim family since the 1840s, while the main consumers of the opium and liquor came from the gambier and pepper planters of the Teochew dialect group, which was controlled by Tan Seng Poh and Seah Eu Chin for a long time (

Trocki 1993a, pp. 250–53). In the early 19th century, the Hokkien and Teochew dialect groups competed fiercely for the bidding of opium revenue farms, but in the mid-19th century, Tan Seng Poh and Cheang Hong Lim decided to join forces to monopolize the opium and liquor revenue market, even expanding their economic activities to Johor and Malacca (

Trocki 1993b, pp. 167–69). The commercial collaboration between Tan Seng Poh and Cheang Hong Lim was not confined to the upper classes of the two dialect groups, but directly affected the socio-economic structure of the dialect groups. The opium and liquor required by the Teochew planters originated from the supply of the Hokkien dialect group; conversely, the Hokkien group’s monopoly on the revenue farm had to do with the support of Teochew’s pepper and gambier planters. It is therefore understandable that some of the Hokkien groups, such as Cheang Hong Lim’s family and interest groups, were closely connected to the Teochew leaders and their laborers. This again refutes the argument that there was little or no contact between the Chinese from different dialect groups.

As for the Hainan dialect group, their population was smaller and it is generally accepted that they migrated to Singapore later than the other dialect groups, as Seah Eu Chin mentioned that there were only 700 in 1848 (

Logan 1848, p. 290). However, by 1881, the population data showed that the number of Hainanese had reached 8319, even more than the 6170 of the Hakka dialect group (

Straits Settlements Legislative Council Proceedings 1881). In 1862, the Hainan leaders Liang Yaguang 梁亚光, Chen Yachun 陈亚春, Chen Yawen 陈亚文, Huang Yaxin 黄亚鑫, and Huang Yafeng 黄亚奉 pooled in money to purchase the old cemetery hill Yushan Pavilion 玉山亭, which was the earliest Chinese cemetery hill of the Hainan dialect group (

Zeng 2007, pp. 84–85). There is no direct evidence mentioned that the Hainan dialect group had joined a “United Front” with the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, since there were exchanges of plaques between the Teochew and Hainanese temples, but no donations from the Hainan community to temples of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. Even

Lim (

1975, pp. 22–23), who proposed the “United Front” theory, was unable to find evidence. The only clue to their relationship with the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups is the “Fuk Tak Chi Two Department Blessing Communal Monument 福德祠二司祝讼公碑” in the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi in 1887 whose content is “The silver donated by Hokkien, Teochew, and Hainan dialect groups, was returned to the temple 内外题福、潮、海南帮所捐签之银,一概归入庙尝” (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 83). However, the inscriptions of the monument also showed that the Hokkien gave donations to the temple, indicating that the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi Temple was consecrated by all the five Chinese dialect groups. It is more likely that the Hainan community experience independent development and maintained a good relationship with all the dialect groups, including the Hokkien, Hakka, and Cantonese communities, instead of joining the “United Front”.

On the whole, the situation of the five major dialect groups in the 19th century could not be simply considered as a “two-level confrontation” (between the Hokkien dialect group and the United Front) based only on the general context of dialect groups. Some of the donations from Hokkien dialect group were evident in the temples pertaining to the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, such as the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi and Wang Hoi Fook Tong temple. The former temple had some Hokkien followers who came to pay their respects and donate incense money. This suggests that even though the Chinese community was distinguished into different dialect groups, this situation did not hinder their interaction. In addition, there is no indication that the Teochew and Hakka dialect groups were clearly aligned to the Cantonese and Hakka side or confronted the Hokkien dialect group. In contrast, these two dialect groups had developed their own cemetery hills and some of their leaders interacted with other dialect groups, suggesting that they were more inclined to adopt a friendly attitude towards all other dialect groups to protect their own interests. Another important point is that the division of dialect groups within the Chinese community did not only exist within the boundaries of dialect groups but could also be subdivided int locality communities or surname communities under each dialect group, such as the Hakka and Cantonese communities could be further categorized into the Kwong Wai Shiu, Jiaying and Fung Wing Tai groups based on their locality identity. Thus, the view of the development of the Chinese community in the 19th century would be limited if viewed solely in terms of a “two-level confrontation”, as the different sub-communities within it developed their own patterns of development, resulting in diverse interactions and connections.

It is clear that in the early years of Singapore, smaller communities within the five major dialect groups were not able to establish their own cemeteries, so the creation of cemeteries in the early Singapore dialect groups was a matter of uniting different locality groups as well as surname or clan groups. For example, although immigrants from southern, central, and eastern Fujian Province belonged to different locality communities, they were buried in Heng San Ting, and the seven locality communities of Cantonese and Hakka also established the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery and Lu Ye Ting based on this principle. It was not until the mid to late 19th century, however, that the economic power of these locality communities increased and led to a change in the development of the Chinese cemetery hills.

4. The Development and Expansion of Cemetery Hills of the Dialect Groups (1850–1900)

In the mid to late 19th century, there were significant changes in the development of the different Chinese dialect groups in Singapore, which resulted in the rapid growth and expansion of cemetery hills of different dialect groups. Prior to the 1870s, although there was a certain degree of communication between the various dialect groups, the British government’s permissiveness towards the Chinese community at that time often led to friction and even riots over social resources and economic benefits. For example, in the 1860s, there were riots by the Chinese secret societies 秘密会社

5 to fight for their interests in Penang and Singapore, both of which were related to the competition and confrontation of dialect group power (

Tan 2016, pp. 50–51). In response, the British government intentionally changed its previous strategy of only appointing Hokkien leaders into the government office. They began to elect leaders of different dialect groups to serve as Justices of Peace, and for the first time, Hoo Ah Kay 胡亚基 of the Cantonese was allowed to join the Legislative Council as a member (

Lim 1975, p. 36;

Daniel 2010, p. 489). This strategy was to increase the interaction and cooperation between leaders of levels of dialect groups, and to facilitate cross-dialect group activities in the Chinese community, in the purpose of reducing friction between the dialect groups and helping the British government to maintain control over the Chinese community (

Daniel 2010, pp. 488–94). The appointment of leaders for each dialect group would also help to strengthen the influence of each dialect group. This strategy was effective, as the total Chinese population increased, the economic power and political discourse of each dialect group strengthened, and cross-dialect group activities became a trend. As a result, there was an increasing number of smaller communities within the dialect groups developing individually. While maintaining relationships with their respective dialect group cemeteries, they also began to create their own community temples, associations, and even cemetery hills, moving the development of cemetery hills in Singapore from the dialect group as a whole to smaller communities operating their own cemetery hills.

On the development of Chinese cemeteries in the mid-to-late 19th century, scholars generally focused on the differentiation of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups from operating Lu Ye Ting together to developing their own cemetery hills by their own locality groups (

Lim 1975, pp. 31–32;

Zeng 2005, pp. 16–19). For a long time after the establishment of the Lu Ye Ting, for example, in 1862 and 1884, the locality groups from Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups jointly raised funds to build and construct the Lu Ye Ting Xin Shan Liji Bridge 绿野亭新山利济桥. Moreover, according to the inscriptions, there is no disharmony among these groups or communities (

Tao 1963, pp. 21–27). However, at the end of the 19th century, the conflict between Kwong Wai Shiu community with Jiaying and Fung Wing Tai communities emerged. In 1886, these groups went to court over the management of the donation to the temple of the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi. In their petition, the Cantonese dialect group (Kwong Wai Shiu), strongly emphasized that they were the founders of the temple and denounced the Hakka dialect group (Jiaying, Fung Wing Tai) as the later groups with the intention of turning against them (

Dean and Hue 2017, pp. 52–53). Although the incident was eventually resolved through the intervention of the British Chinese Protectorate 华民护卫司, it undoubtedly revealed the rift between these three groups. The split between these three groups should not be seen as mere conflict and confrontation between the two dialect groups. The Huizhou community, which is part of the Kwong Wai Shiu community, belongs to Hakka dialect group, but it stood on the Cantonese side to complain about the encroachment of the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi by the Hakka community of Jiaying and Fung Wing Tai communities. The dispute over the seven communities of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups is therefore a reflection of the rift that had developed among the locality communities of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups.

Under this context, Kwong Wai Shiu established the Peck San Theng 碧山亭 in 1870 (

Dean and Hue 2017, pp. 828–29). By the 1880s, the Fung Wing Tai and Jiaying communities of the Hakka groups had established the Yyushan Pavilion 毓山亭 in 1882 and Shuang Long Mountain 双龙山 in 1887 respectively (

Dean and Hue 2017, pp. 580–81). The leaders of the three communities took turns to be appointed as chairmen of Lu Ye Ting, and they worked together to develop the cemetery hill until it was expropriated by the government in 1957 (

Tao 1963, pp. 2–6). The development of Cantonese and Hakka cemetery hills in the 19th century shows that although the three communities developed independently, the relationship between them was not completely severed, and they were still linked by the Lu Ye Ting (

Zeng 2005, p. 34). Returning to the lawsuit that broke out in 1886 over the incense money of the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi, it is understandable that the Kwong Wai Shiu group intended to emphasize their dominance over the temple at this time. As mentioned above, the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi was originally founded by the Kwong Wai Shiu group, and the Jiaying and Fung Wing Tai groups only succeeded in joining the leadership of the temple after they had joined the former group in the cemetery hills. However, as the three communities began to move towards their own development on cemetery hills in 1870, the relationship between them naturally changed, and it is understandable that the Kwong Wai Shiu group wanted to take back the management of the temple at this time to mark the community’s move towards independence, rather than “sharing” the temple with the Fung Wing Tai and Jiaying groups.

Lim (

1975, pp. 30–31) suggests that the individual development of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups was because cross-dialect group activities had become a trend at the time, and that the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups no longer needed to form a “United Front” to counteract the Hokkien dialect group. However, Lim only discussed the development of cemetery hills and the Chinese community from the perspective of the dialect groups. However, the situation of isolation of the three Cantonese and Hakka communities was not only related to the political changes in the external environment of the dialect groups, but also attributed to rapid population growth and economic empowerment within the Chinese community. In the mid to late 19th century, the Chinese population in Singapore underwent drastic changes, with an increase in population from about 40,000 in 1848 to 80,000 in 1881, and then doubled to 160,000 in 1901 (

Straits Settlements Legislative Council Proceedings 1881). Between 1848 and 1881, the number of Cantonese increased sharply from 6000 to 14,853, while the Hakka dialect group also increased from about 4000 to 6170 (

Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Colony 1881).

As the population increased, the different locality groups within Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups became more efficient in running their own cemetery hills, rather than having to share the cemeteries with other locality communities due to lack of financial means, as they had done previously. Although the locality groups were united in the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups cemetery hills, this did not mean that their locality group identity had been diluted. For Lu Ye Ting and Haichun Fuk Tak Chi, the seven groups from Cantonese and Hakka were not truly integrated with each other, they were working together while maintaining their own community. For example, the leadership structure of Lu Ye Ting was distributed according to the power of the three communities, and the donations to the temple and the cemetery were made in the name of each community (

Tao 1963, p. 4). This suggests that although the three communities worked together to run the cemetery, they maintained their own locality identity in the process of cooperation. Therefore, when the social power of each community was strengthened, it became a trend to develop and run their own community cemeteries on their own.

This did not only happen in the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups but as the population of the Hokkien dialect group doubled and became the largest dialect group in the region with over 30,000 people in 1881 (

Straits Settlements Legislative Council Proceedings 1881), the locality communities within the Hokkien dialect group such as Yongchun group, Jinmen 金门 group from Quanzhou and Changtai 长泰 group from Zhangzhou established their own locality associations or temples (

Lim 1975, p. 16). In addition, the surname groups within the Hokkien dialect group also established blood-related organisations, such as Po Chiak Keng Tan Si Chong Su 保赤宫陈氏宗祠 by the Tan clan 陈氏 and the Hong’s Swee Kow Kuan Kueh Hua Kwan 水沟馆葛岸馆 by the Hong clan 洪氏 (

Dean and Hue 2017, p. 203). In addition, many burial hills of surname association appeared at the time, such as Hokkien Khoo and Zeng’s Hill, Hokkien Chua’s hill, Hokkien Wong’s hill, Hokkien Yeoh’ hill (

Table 2). As illustrated above, the Hokkien dialect group had a number of powerful Peranakan families from Malacca, with the Zeng, Chua, and Khoo surnames having been the major Hokkien immigrant families in Malacca and the earliest Hokkien immigrants to Singapore. It is therefore not surprising that the family created their own surname association cemetery hills based on blood ties at the later stage.

According to the research of Chinese temples in Singapore founded in the 19th century by

Dean and Hue (

2017), there were only 13 temples established before 1850, many of which were general institutions of various dialect groups such as the Haichun Fuk Tak Chi, Wak Hai Cheng Bio and the Thian Hock Keng Temple. However, between the years 1850 and 1900, a total of 30 temples or organisations were established by the Chinese society, most of which were established by the smaller locality or surname-based communities. Among them, the smaller locality groups of Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups had established four locality associations 会馆 during this period, including the Tai Po Association 大埔会馆 and Fung Shun Association 丰顺会馆 from the Hakka community, and the Panyu association 番禺会馆 and Kong Chau association 岡州会馆 from the Cantonese community (

Dean and Hue 2017, pp. 315, 673, 749, 779). The donation monuments at Chinese temples and cemetery hills show that the establishment of these Chinese organizations was dependent on donations from their communities (

Jao 1970, pp. 8–9). The proliferation of Chinese locality and surname-based organizations in the mid-to late-nineteenth century reflects that, as the Chinese community grew in population, small communities under the dialect groups became financially strong enough to develop their own community organizations. Although more smaller communities developed independently, this did not mean that they were completely fragmented, as the highest institution of the dialect groups, such as the Thian Hock Keng of the Hokkien dialect group and the Ngee Ann Kongsi of the Teochew dialect group, were still able to unite and integrate the small communities. These small communities developed on their own but were still linked to the dialect groups as a whole.

Among the dialect groups, the Teochew and Hainan communities had done the most to unify their smaller communities, as the two dialect groups have not developed their cemeteries into smaller communities of locality or surname cemetery hills, unlike the Hokkien, Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups. After the Taishan Pavilion, the Ngee Ann Kongsi 义安公司 under the control of Seah family acquired six cemetery hills in different parts of Singapore and obtained a charter from the British government in 1933, occupying a total area of about 400 acres of cemetery land (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1933). It is believed that all these cemetery hills were opened and occupied in the mid to late 19th century (See

Table 4). It also reflects the strong financial strength of Ngee Ann Kongsi. In fact, from the 1860s onwards, there were already some voices of dissatisfaction within the Teochew community towards the monopoly of the Seah family of Chenghai group in Ngee Ann Kongsi. The Haiyang group established four locality and surname-based associations—Singapore Hoon Yong Kong See 新加坡勋永刚会, the Teochew Kang Hay Tang 潮州康熙堂, the Teochew Sai Ho Association 潮州西河会, and the Teochew Lee Clan Association 潮州李氏宗亲会, to challenge the position of Chenghai group in the Ngee Ann Kongsi (

Yen 2017, p. 82). However, the Seah family and its affinity with the Tan Seng Poh family had long controlled the gambier and pepper planters of the Teochew community (see above), the other locality or surname groups would not be able to challenge the dominance of the Seah family (

Yen 2017, p. 82). The power structure within the Teochew community could also be divided into smaller communities, but their power was too weak and was completely suppressed by the Seah family of the Chenghai group. This means that the smaller groups, such as the locality communities of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, found it hard to build their own cemeteries.

The rapid growth of the immigrant population of the Hainan dialect group (8319 people in 1881) led to the expansion of the Yushan Pavilion, with the acquisition of three plots of land covering 29 acres in 1962 (See

Table 4). Later, in 1891, two more lots of more than 30 acres of land next to the Yushan Pavilion cemetery hill were purchased by the forefathers of Hainan to create a new cemetery hill, so that Yushan Pavilion 玉山亭 had two cemetery hills, the old and the new, which were managed by the Thean Hou Temple 天后宫 of the Hainan community (

Zeng 2007, pp. 84–85). The Hainanese was relatively late in establishing a foothold in Singapore, and its power was the weakest among the five dialect groups. The cemetery hills belonging to this dialect group were therefore created late, and both cemetery hills were purchased by wealthy businessmen from the Hainan group and donated to the whole Hainan community (see above). It shows the very different creation of their communal cemeteries from the other dialect groups, since the other communities would raise the money from different classes of their dialect group to create the mounds, but for the Hainan community, the cemetery was donated by a few merchants to the public. The establishment of both the old and new Yushan Pavilion reflects the lack of economic power of the Hainan dialect group, making it unlikely that a locality or surname group would have developed its own cemetery on its own.

This is also the case with the Sanjiang 三江 group, which was even more inconspicuous than the Hainan dialect group and the most sparsely populated. The Sanjiang group did not belong to a dialect group but referred to a group of immigrants from Jiangsu 江苏, Jiangxi 江西 and Zhejiang 浙江 in China, who united to form their own single community because of their relatively sparse population in Singapore. In 1898, they established the Sanjiang cemetery, Jingshan Pavilion 静山亭, (see

Table 4). As can be understood from the case of the Sanjiang group, the Chinese community’s establishment of a cemetery hill is not necessarily based on the attributes of the dialect group but is often influenced by the internal situation of the respective community. If the internal strength of a particular local community is not sufficient, they would choose to merge into a larger community to build a cemetery, such as the Teochew, Hainan, and Sanjiang groups. However, the cooperation between these internal communities was not necessarily static. Once the locality communities gained more economic power, they would try to separate from the dialect group and develop independently. This is the case of the three communities, Kwong Wai Shiu, Jiaying, and Fung Wing Tai of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups.

In the broader context, more and more of the smaller communities within the Chinese migrant society, including both locality and surname communities, became independent in the 1850s. This was reflected in the construction and development of cemetery hills as well as the emergence of Chinese temples, associations and ancestral halls. The establishment of the Singapore Thong Chai Medical Institution 新加坡同济医院 in 1885 was supported and donated by all classes of the Chinese community from different dialect groups, and cooperation between the Chinese dialect communities reached an unprecedented peak (

Lim 1975, p. 35). This was, of course, something that the British colonial government was contented to see. When the Chinese community was keen to move towards the independent development of the smaller communities, the cohesion between the dialect groups would be weakened, which not only greatly reduce the confrontation and conflict between them, but also helped the British government to control the Chinese community. From the establishment of the Chinese Protectorate in 1877 to the enactment of the Societies Registration Act in 1892, the British government gradually controlled the Chinese community in outlawing the secret societies (

Tan 2016, pp. 38–40). However, at this stage, as early as the year 1864, J.T.

Thomson (

1864, pp. 280–81), a British colonial official, had already pointed out that the endless mounding of the Chinese cemetery hill in Singapore was cluttering the local environment and turning the city into a large Chinese cemetery.

In the 1880s, the British government intended to introduce a Burials Bill 殡葬法案 to control the Chinese cemetery hills, but it was not until 1895 that this bill was passed (

Proceedings of the Legislative Council of the Straits Settlements 1887a, p. B101;

1887b, p. B164). However, the British government policy could not prevent the rapid expansion of Chinese cemeteries at the time, and as mentioned above, many cemeteries were stil created after the 1880s. For example, according to our fieldwork, the Hokkien Huay Kuan 福建会馆 opened up more cemetery hills beyond Heng San Ting, such as New Heng San Ting 新恒山亭 and Lin Kee Cemetery 麟记山, to solve the problem of overflowing cemeteries. It is clear from this that at least until the 20th century, although the British government gradually adopted control measures over the Chinese community, they were unable to stop the rapid growth of the Chinese cemetery hills. Hence, the mid to late 19th century was still the golden period for development of the cemetery hills established by the various dialect groups.

5. The Response and Transformation of Chinese Cemeteries in the 20th Century

In the 20th century, the British government had gained full control of Singapore, and the Chinese were also affected by these policies. The British government had vigorously weakened the influence of the dialect group power on the Chinese society by outlawing secret societies, abolishing the revenue farm system 饷码制度 monopolized by Chinese leaders, strictly regulating the registration ordinance of societies, and appointing the pro-British Straits Chinese as representatives of the colonial government (

Daniel 2010, pp. 494–501). During this period, Singapore was on the verge of booming development, and both the population boom and the shortage of land prompted the British government to expropriate Chinese cemeteries intentionally and compulsorily for development purposes (

Yeoh 1991, p. 287). In addition, the spread of Chinese nationalism to the Nanyang Chinese areas also had a significant impact on the ideology of the Chinese in Singapore. Both external government policy factors and internal ideological changes directly influenced the development of the local Chinese cemeteries and even the development of the entire Chinese secret societies. It is common for scholars to view the Chinese community’s response in terms of government policy, and most believe that the Chinese community was passive on the issue of cemetery development in the 20th century. However, this argument ignores the autonomy of the Chinese community in promoting the development of cemeteries. In addition to the external environment, the fate of these dialect groups’ cemeteries was also related to the internal development of each community, as not all of them ended in total expropriation and disappearance.

Since the late 19th century, the British government had been expropriating the cemeteries regarded as a hindrance to the planning and construction of the city. The oldest cemetery in the Chinese community, Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery, and Heng San Ting were the first to bear the brunt. The reason was because these two cemeteries were the earliest cemeteries established by the Chinese community, and their location was closer to the center of urban development than the cemeteries that were created later. In 1907, the British government decided to expropriate the land of the cemetery hill in order to implement The Telok Ayer Reclamation Scheme in the Tanjung Pagar area where the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery was located. An amount of

$10,000 was allocated to the affected parties for the reburial of the cemeteries (

Song 1993, p. 333). In 1907, the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery was expropriated (

Tao 1963, pp. 56–57). From 1882 to 1921, according to our team’s field research and newspaper sources, the land of Heng San Ting was gradually expropriated and moved to Kopi Sua 咖啡山 and Lao Sua 老山, which belonged to the Hokkien Huay Kuan, because the government built a hospital. Unlike the Green Mountain Pavilion Cemetery, the cemetery hills at Heng San Ting were not fully expropriated, and some of its lands remained until it was officially closed in the 1970s. However, most of the early immigrants’ graves were moved to Laosua at this time, which later became part of Bukit Brown cemetery hill. Our team succeeded in collecting data from more than 400 early Chinese immigrants’ graves at this site (see content above).

The passage of the Burial bills in 1895 meant that the British colonial government was all set to expropriate the land of the Chinese cemeteries, banning illegal private Chinese graves, and curbing the expansion of cemetery hills (

Yeoh 1991, p. 296). However, during this period, as the population of the Chinese increased as well as an increase in the number of death, the British government’s control of cemetery hills did not prevent the expansion of Chinese cemetery land or even the illegal construction of private cemeteries.In the early 20th century, the Chinese Reformist leader Lim Boon Keng 林文庆 suggested to the British colonial government to build a new public cemetery for the Chinese to solve the overcrowding problem of the Chinese cemetery hills (

Song 1993, pp.333). It took more than ten years before the government agreed to their request and acquired part of Wong’s Taiyuan Hill 太原王氏 and Lao Sua’s lots to open up Bukit Brown under the jurisdiction of the city government (

Malaya Tribune 1917,

1918).

In the mid-1920s, a second major clean-up of the cemeteries was carried out by the British government. Since then, the cemeteries of the different dialect groups as well as the private cemetery hills of some families, such as the tombstone of Tan Tock Seng, Cheang Hong Lim, and Seah Eu Chin families were also moved to the public cemetery of Bukit Brown. This represented a gradual erosion of the Chinese rights in running the cemetery hills as Bukit Brown is a public cemetery controlled by the council and is not subject to dialect groups or any smaller communities of Chinese society. Bukit Brown was not favored by the Chinese community when it was opened, and few Chinese chose to be buried there. Apart from the fact that the cemetery was not managed by a dialect group, the Chinese also protested against the government because of the small size of the cemetery, and they were unable to choose a suitable burial site based on feng shui (

Yeoh 1991, pp. 307–9). To the Chinese community, the fengshui of their graves was crucial in determining the destiny of their future generations, and the size of the grave was regarded as a display of the individual’s grandeur (

Chong and Chua 2014, p. 31). To solve this problem, the cemeteries of Bukit Brown compromised by enlarging the size of each burial grave, and data shows that as a result, the number of Bukit Brown Chinese cemeteries increased from 3% in 1922 to 42% in 1929 (

Yeoh 1991, p. 310), indicating an increase in acceptance by the Chinese community. The Chinese community’s willingness to make changes to their traditional afterlife attitudes was not only influenced by external government factors, but the other reason was that the leaders of the Chinese community such as Tan Kah Kee 陈嘉庚 and Lim Boon Keng 林文庆 called upon the Chinese to change their afterlife perceptions and burial methods (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1936).

Lim Boon Keng and Tan Kah Kee, as representative leaders of the Hokkien dialect group, were inspired by the ideas of the New Culture Movement in China at the time. They strongly advocated the Hokkien dialect group to abandon the traditional ideas of the Chinese and to reform the traditional culture and concepts, by opposing superstition and reforming the traditional burial and extravagant burial culture (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1936). They opposed the Chinese concept of burial and promoted the construction of Bukit Brown Chinese cemetery hills as they believed this would solve the problem of the overcrowded and excessive Chinese cemetery hills. They also hoped that the Chinese community could move beyond the narrow sense of dialect groups and locality communities’ identity, as well as replace the excessive pursuit of post-mortem burial culture, by focusing on the political situation and future direction of China, and devote themselves to the cause of revitalizing the Chinese nation (

Lim 1975, pp. 36–38). The Hokkien community leaders’ advocacy for funeral innovation was echoed by the dialect group, not only reducing the proliferation of Chinese burial mounds, but also to some extent alleviating the need for public mounds for the dead.

In addition to the Hokkien dialect group, the Teochew dialect group leaders also adopted different strategies for the development of their cemeteries. The Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan 潮州八邑会馆, which succeeded in taking over from Ngee Ann Kongsi of the Seah family in 1930, also took on a more liberal view of the expropriation and development of cemetery hills. In 1933, the Ngee Ann Kongsi 义安公司 adopted a new constitution which also provided for the commercialization of part of the unused cemetery, it stipulated that “those who do not need to use it for cemetery purposes are free to develop it for building or other business purposes 无需用为墓地者得自由发展,以为建筑或其他事业之用” (

Lyu 1952). Later, they razed part of the land of Taishan Pavilion for construction and even rented out the garden for planting flowers (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1936). These practices of the dialect group testify to a change in their attitude towards the cemetery hill and a more modern attitude towards the treatment of the afterlife and the new use of the cemetery in the future.

For development of the post-World War II period, Kwong En Hill 广恩山, a cemetery hill of Chaozhou community, located near Awareness Road, was expropriated in 1950 to support the government’s construction of a tuberculosis hospital. Six years later, all the cemetery site was expropriated and most of the cemeteries were relocated to Kwong Tak Hill 广德山, also owned by the Ngee Ann Kongsi (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1951b). Since then, the economic value of the cemetery hill land was a major source of inspiration for the leaders of the Teochew dialect group. The directors of the Ngee Ann Kongsi actively proposed the razing of Taishan Pavilion for housing, and the plan was approved by the government in 1951, resulting in the complete relocation of over 20,000 tombs in cemetery hill within two years, with most of the skeleton remains being moved en masse to the Teochew’s Kwong Tak Hill Cemetery (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1948,

1951a). Instead of clinging on to the old dialect of cemetery hill, the leaders of the Teochew dialect group were quick to adapt to the development of the city and actively sought changes to their cemetery hill.

The approach of the Teochew leadership had to do with the Teochew Poit Ip Huay Kuan taking over the leadership of Ngee Ann Kongsi from the hands of the Seah family, and the company ran into serious financial difficulties (

Choi 2016, pp. 200–5). Under the new leadership, Teochew leaders adopted the strategy of using the cemetery hill for commercial purposes to better ensure the continued development of Ngee Ann Kongsi and to maintain the cohesiveness of the Teochew dialect group. However, this does not mean that the Teochew dialect group has stopped focusing on the operation of cemetery hill. Instead, they adopted a win-win situation by opening up a site at Kwong Tak Hill as a Teochew communal cemetery hill, where the unclaimed bones from other cemetery hills that were expropriated were cremated and relocated for burial and worship, to honor all the Teochew ancestors who moved here (

Nanyang Shang Pau 1951a). Kwong Tak Hill was closed in 1977, but a small portion land of Kwong Tak Hill remains today, and still exists as a place of worship for the Teochew ancestors. The Teochew dialect group had taken a proactive approach towards its cemetery hill, seeking the best course of action to sustain its development.

Unlike the Hokkien and Teochew dialect groups, the leadership of the Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups fought hard for the retention of the land on the cemetery hills and negotiated with the government when they received news of the intention to expropriate their land. In the early 20th century, the leadership of Lu Ye Ting noticed the unstoppable trend of expropriation of the cemetery by the government, and to better defend their rights, Lu Ye Ting set up a “trustee system” 受托人制度 in 1927 to negotiate land acquisition with the British colonial government (

Zeng 2005, p. 22). Before World War II, the government expropriated Lu Ye Ting’s land several times for urban development, and the latter actively negotiated with the government to retainsome land and receive compensation accordingly (

Zeng 2005, p. 31). The British colonial government intended to expropriate Lu Ye Ting’s land for municipal construction in 1957 and agreed to set aside five acres of land in Choa Chu Kang 蔡厝港 for the construction of a new cemetery hill to accommodate Lu Ye Ting’s new burial ground (

Tao 1963, p. 6). At that time, more than 11,500 bones were removed for cremation and buried in a new cemetery owned by Lu Ye Ting in Choa Chu Kang 1958 (

Zeng 2005, pp. 37–42). The relocation of Lu Ye Ting’s cemetery can also be seen as another new phase in the development of Chinese cemetery hills in Singapore, as the government intended to expropriate all the hills one after another, meanwhile only retaining the Choa Chu Kang Cemetery Hill 蔡厝港坟山 in the north suburb in Singapore (

Han 2015).

After World War II, both the urgency of urban population and the shortage of land space accelerated the expropriation of cemetery hills by the British colonial government and later by the government of Singapore after achieving independence (

Yeoh and Tan 1995, p. 186). The People’s Action Party (PAP) government, which had been in power since 1959, took a tougher stance than the British government on the issue of cemetery hills expropriation. In the 1960s, the newly independent Singapore government gave the Housing and Development Board (HDB) greater power to acquire any land that was not used for market value for development, and the land used to build cemetery hills was considered to have no “market value”. In 1965, the “Master Plan” 总体规划 focusing on the development of land in Singapore was introduced to gradually enhance the acquisition of cemetery hills in Singapore (

Singapore Planning Department 1967, p. 11). The introduction of the government land development plan was not only intended to build and develop the city, but to guide Singapore citizens towards a national identity (

Yeoh and Tan 1995, p. 187). This is because in the view of the government, the Chinese cemetery hills had a strong dialect characteristic, which would divide the Chinese community. This was not conducive to the cohesion and unity of the various ethnic groups in Singapore (

Yeoh and Tan 1995, p. 187). Therefore, it was urgent and necessary to occupy the land of the dialect group and even the cemetery hill to build HDBs on their land to shape the national identity of Singaporeans (

Yeoh and Kong 1996, p. 56). From the 1960s to the 1970s, Hokkien surname hills, such as the Yeoh, Lim, Lee and Chua’s as well as the Leizhou Mountain Cemetery of the Cantonese dialect group were expropriated by the government and a large number of skeletons from the graves were moved to Choa Chu Kang Cemetery Hill.

However, not all cemetery hills were passively confronted with the fate of land expropriation at this time. After the Lu Ye Ting was completely expropriated, the cemeteries of the three groups of Cantonese and Hakka dialect groups, Peck San Theng, Yyushan Pavilion Shuang Long Mountain, which the government did not confiscate for the time being, more land was purchased to house the graves that had been relocated (

Tao 1963, pp. 1–2). According to statistics, Shuang Long Mountain absorbed 66 graves, Yyushan Pavilion absorbed 236 graves, and the Peck San Theng absorbed 84 graves from Lu Ye Ting (

Tao 1963, p. 3). The most prominent of these was the expansion of the Peck San Theng, the cemetery of the Kwong Wai Shiu community, where the addition of seven cemetery hills in 1948 increased its size from 107½ acres to 253 acres, and by 1973, the land at Peck San Theng had expanded to 324 acres (