A Needle in a Haystack: Looking for an Early Modern Peasant Who Travelled from Spain to America

Abstract

:1. Introduction

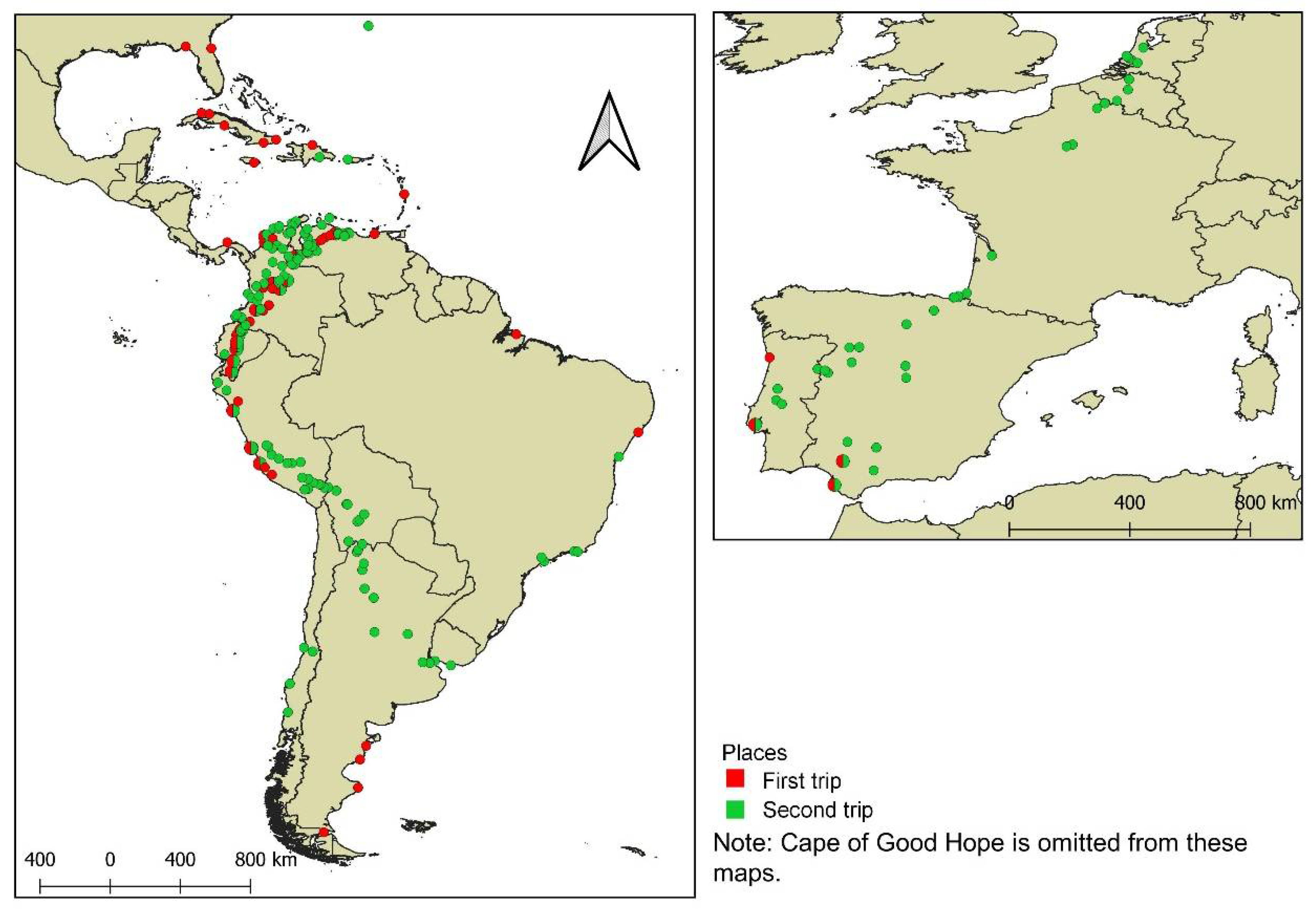

2. The Account about Robles’ Travels

3. How to Find a Peasant?

He declares that he is original [natural] from the said town [villa] of Moral, of the age of 45 years, more or less, legitimate son of Juan Ruiz de Robles and Ana de Montes his natural parents, his father from the said town his mother from that of Almagro where they were known as honest people in their sphere. Being in his homeland [patria] acting as a peasant [labrador], wishing not to limit himself to these narrow terms, see the world and serve his Majesty left his home last year in 1688 without further motives that the ones mentioned.17

4. How to Find a Traveler?

4.1. Traveling as a Soldier

He went to Andalusia, arrived in Seville and because some levies were made there, he was induced to take a place as a soldier in a company that was raised on behalf of Captain Don Juan de Ayala for the fort [presidio] of San Agustín de la Florida.32

4.2. Robles′ Transformation into an Independent Traveler

4.3. Traveling and Memory

He arrived [in Quito] and having separated from his benefactor with due recognition, he went to an inn [posada], but having learned this the president of that royal tribunal [audiencia] Don Mateo Mata Ponce de Leon, his countryman, ordered him to go to his house where he made him stay and very well with great attention and fineness to which he responded submissively, telling him what he had walked, seen, and recognized in his long pilgrimages, seeming to be in the service of the king, which he had not done with anyone else.41

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

| 1 | For America, this is visible at first glance if we look at the Index of the Atlas of Spanish Explorers, where 78 travelers from the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries and 66 from the period between 1735 and 1802 are mentioned. For the seventeenth century, there are only eleven Spanish travelers, all of them missionaries, nobles or seafarers (Sociedad Geográfica Española 2009). One of the best and most cited books about travelers and travel accounts, by Pratt ([1992] 2008), focuses on the period from 1750 to 1850; but the bibliography about travel accounts is vast. For an overview about the bibliography on early modern travel writing, see also Classen (2018). |

| 2 | The folios of the document are not numbered so we have made an artificial numbering observing recto and verso (Declaración de Gregorio de Robles, 1704, AGI, Charcas 233, f. 1r; hereafter, AGI Charcas 233). |

| 3 | An exception are his stays in Lima; when he went there for the first time, he stayed for two years. |

| 4 | On the concept of conviviality, see Nowicka and Vertovec (2014). Maria Sibylla Merian International Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities and Social Sciences Conviviality-Inequality in Latin America (2019) and Freitag (2013). |

| 5 | It should be pointed out that Corbin deliberately chose by chance a completely ordinary person without any special legacy and that Pinagot, quite differently from Robles, never left his home district. |

| 6 | In Robles’ account, it is stated that Bustamante was part of the war council (“Consejo y junta de Guerra de Indias”). AGI Charcas 233, f. 1r. Tau Anzóategui (1980) confirms this last statement in his footnote 1 based on secondary sources. |

| 7 | We confirmed that the signature and handwriting is that of Bustamante by comparing it to other documents written and signed by him, such as AGI Filipinas, 204, N.1. In this document, the signature by Bustamante is visible in photos 68, 162 and 1007. Another example is Archivo General de Simancas (hereafter AGS) EST, LEG, 3,633,191. Here, the signature appears in photo 4 in the version digitalized in pares.mcu.es. |

| 8 | The one critical observation states that it is not true that there was a rich gold mine in the Cardeña mountains in Spain, as Robles states. It literally says “en esto habla con corta inteligencia porque no hay mina de oro que sea como supone”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 88r. Another note adds something: When Robles talks about his passing through the Hague, he mentions that he was looking for a minister there who he did not find. Here, the observation adds that the minister’s name was Francisco de Quiros and that he had already left the Hague: “Este dice era don Francisco de Quiros que ya había salido del Haya”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 86r. |

| 9 | Philippe Castejon, personal information in November 2021. Charcas 233 is a collection of many documents related to that jurisdiction entitled “Cartas y expedientes de personas seculares del distrito de la audiencia años de 1690 a 1707”. We reviewed one by one all the documents, and there is no other one related to Robles or to Bustamante. We also looked for all other documents in the archive signed by Bustamante, and Robles was nowhere. |

| 10 | The Historia General de España speaks very badly about Bustamante due to supposed corruption and greed. He was associated with the count of Oropesa who fell in disgrace in the War of Succession (Lafuente and Valera 1889, pp. 119–224). |

| 11 | Folger and Simon (2011, pp. 29–30) list as defining elements of the reports of merits and services the self-promoting nature in order to receive a compensation from the crown and the channeling by bureaucracy to the Council of the Indies. They also report the bureaucratic steps these reports normally took, which are not at all followed in Robles’ case. |

| 12 | One out of many examples is the following: Archivo General de la Nación, México (hereafter AGNMe). 1540. Indiferente Virreinal, Caja 5001, Exp. 66. |

| 13 | Brendecke (2009, p. 235) mentions that the relaciones de méritos y servicios constituted “the most impressive examples of unrequested information” contributing to the entera noticia. |

| 14 | “Desde aquí empieza a tratar de las provincias que comprende el nuevo reino de Quito y Popayan”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 57v. |

| 15 | The author added 41 footnotes with comments on the text, based principally on bibliography and a few edited sources. He commented also on the dates that he considered were wrong, on the names (of places and persons) and surnames he corrected because they were incorrectly written, and he also added information on some facts that Robles mentioned briefly. The notes that are on the margins in the manuscript are also transcribed as footnotes without personal comments. The book has also illustrations and titles that are not present in the manuscript. |

| 16 | What we have written in the next two sections took a lot of time, consultation with fellow specialists in Spanish history and travelers, doubts, and frustrated archival work. |

| 17 | “Declara es natural de la dicha villa de Moral, de edad 45 años poco mas o menos hijo legítimo de Juan Ruiz de Robles y Ana de Montes sus padres naturales, su padre de la dicha villa su madre de la de Almagro donde fueron conocidos por gente honesta en su esfera. Que hallándose en su patria en el ejercicio de labrador, deseando no limitarse a aquellos cortos términos, ver el mundo y servir a SM salió de su casa el año pasado de 1688 sin mas motivo que el expresado”. AGI, Charcas 233, fs. 1r and 1v. |

| 18 | Both Donézar Díez de Ulzurrun (1996) and the Diccionario de Autoridades (Real Academia Española n.d.) agree with this broad definition. |

| 19 | In the Castilian archives, there were very few digital catalogues and they were not very detailed. Therefore, we had to go through all the documents of certain years and places box by box and document by document. This applied among others for baptismal records, marriage dispensations and notarial protocols. The national archive in Madrid (as well as the AGI) is integrated into the Spanish online catalogue PARES, which is very helpful but far from being complete. In the national archive, we additionally used more exhaustive digital catalogues available in the archive and catalogues on paper in order to identify documents about Moral de Calatrava and people in contact with Robles. |

| 20 | Poska (2005, pp. 15–16), looking for illiterate early modern peasant women in Galicia, employed a similar methodology. She tells us that nearly all the records about them were produced by “the Catholic Church and the Castilian legal system.” She also rightly points to the fact that notarial records did often not contain information about the poorest members of the society, both for the fact that they had no money to pay notaries and not enough belongings to “lease, sell or pass down to their descendants”. For specific occupational groups, there sometimes exist additional sources such as documents from guilds; these might even attest for mobility, such as in the travel books of early modern journeymen (Barnert and Schlüter 2018, pp. 65–71; Wiesner 1991). |

| 21 | Personal information by Cristian Bermejo Rubio, the archivist of the historical archive of the archbishopric of Toledo, September 2021. |

| 22 | Miguel Ángel Jiménez, personal information via e-mail, el 11 July 2021. Here, it has to be noted that contacting local and even more local ecclesiastical archives is not always easy. Sometimes they do not have a webpage or the contact information available there is not up to date. Sometimes, such as in the case of the Municipal Archive of Moral de Calatrava, they do not even have permanent staff attending the archive. It has to be pointed out, however, that we have been very fortunate to have met with people, some of them working in other parts of the administration who have been very kind and helpful with providing information about the archives, such as the current priest of Moral, Miguel Ángel Jimenez, the staff from the Tourism department of Moral de Calatrava, the director of the Municipal Archive of Almagro and María de los Ángeles Herreros Ramírez, who is currently Subdelegada del Gobierno in Ciudad Real but had once worked organizing the municipal archive of Moral. |

| 23 | In Spanish America, the equivalent tribute registers and the related visitations are abundant everywhere and are highly useful sources regarding the categorization of vassals of the Spanish Crown. See Gil Montero (2020) and Albiez-Wieck (2017). |

| 24 | In a notarial protocol from Malagón, dating from 1653, Don Bernardino de Mena y Balverde is mentioned as “absent in the Indies”. He was the husband of Doña Catalina de Balverde who hosted Robles twice in Mompós: AHPCR, Protocolos Notariales 1651-1659, f. 31r. See also Gil Montero and Albiez-Wieck (2019). |

| 25 | María de los Ángeles Herreros Ramírez, personal information, September 2021. |

| 26 | The encomienda was a tax-farming institution which was also exported to the Spanish territories in America and the Philippines. About the Spanish military orders in the seventeenth century, see Postigo Castellanos (1988). About the encomiendas of the military orders, see Fernández Llamazares (1862, chp. X). |

| 27 | The entire Catastro is also available online: Catastro del Marqués de la Ensenada de 1750a. |

| 28 | García González and Gómez Carrasco (2010, p. 106) tell us that the limited representation of the upper nobility in Castile La Mancha from the sixteenth century onwards was due to the fact that most of the land belonged to the military orders. |

| 29 | Eustaquio Jiménez Puga, the archivist of the Almagro archive kindly provided us with the only census (padrón) from the neighboring town of Almagro, from which Robles’ mother originated. It dates from 1695 and is only a part of the original census, containing a list of poor people and widows. This list does not contain the name Ana de Montes, but another person with the same surname: Phelipe de Montes, living in the Calle de la Claberia (f 3r). Additionally, the surname “de Robles” appears (f. 4vs, f. 5vs). Additionally, in the Catastro de Ensenada from Moral dating from 1750, the surname “de Robles” appears several times. There is a mention of a Francisco de Robles who was renting land; a mention of a Martin de Robles who owned a house in Moral, and Maria Ramona and Ysabel de Robles, single girls. It is said that they belong to the “general state” (“su estado el general”) (Catastro del Marqués de Ensenada de 1750c). |

| 30 | In his appendix I, the author shows data on the evolution of the total population of Moral in 1591 (2824 inhabitants), 1625 (2362), 1646 (2284) and 1690 (2525). |

| 31 | The petitioners, labradores from Moral and the neighboring Valdepeñas, asked for permission to temporarily rent out their commonly owned pasture (dehesa) in order that cereals might be grown there. Due to the plague, there was a famine in the region, and they needed the money from the rent to buy cereals for the starving population. Their request was granted and renewed after several years. |

| 32 | “se encaminó a Andalucía, llegó a Sevilla y por hacerse allí algunas levas le indujeron a que sentase plaza de soldado en una compañía que se levaba de cuenta del capitán Don Juan de Ayala para el presidio de San Agustín de la Florida”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 1v. |

| 33 | Very helpful with our search were various talks with specialists, some of which occurred during the long waits for AGI shifts in the context of the pandemic. We are grateful to Juan Marchena and his long conversations about archives, pirates, and Caribbean Jews; to Christian de Vito and his enormous knowledge of presidios and global history; as well as to Philippe Castejón who guided us through the labyrinth of seventeenth-century bureaucracy. |

| 34 | Tau Anzóategui (1980, p. 28) reaches the same conclusion but based on bibliography that refers to the fleet of General José Fernandez de Santillán, with which Ayala traveled. |

| 35 | “se dedicó a esto con tanto celo, diligencia y caridad que puede decir se preservaron muchos de perder la vida en fuerza de su cuidado”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 2v. |

| 36 | Tau Anzóategui (1980) considered that Robles stayed in Cuba until 1693. He argued that Robles confused the date of a political disturbance that occurred in Santiago in 1693 (and not in 1690), a confusion that would have implied a longer stay in Cuba, something that cannot be inferred from his account. Furthermore, Port Royal—where Robles docked in Jamaica immediately upon leaving Cuba—was destroyed by an earthquake in 1692, after Robles’ passage through the island. For this reason, we do not take into consideration Tau Anzoátegui’s comments regarding this and other dates. |

| 37 | The text literally states: “De allí volvió a Puerto Real pero antes reconoció toda la isla andándose de estancia en estancia con voz de que estaba recibido en el asiento de negros y que iba a examinar si había alguna de venta pues de otro modo no se la hubieran permitido”. AGI, Charcas 233, f. 10r. |

| 38 | The search methodology in the archive was threefold: in the digital catalogues (both those that are online and those that the AGI offers within the archive), we searched for (1) the names of the people with whom Robles interacted and (2) the places he passed through. We also requested and consulted (3) all possible files dated between 1687 and 1704, originated in the jurisdictions he visited. As AGI documents are usually in large folders along with many others, we reviewed one by one all the attached documents. |

| 39 | “Desembarcose, fue al Pozo y quedose en aquella pequeña isla en una estancia de Juan Bernal y vio que aquella noche llegó allí un comboy de Jamaica con dos balandras que conducían harinas, negros y géneros de comercio prohibido”. AGI, Charcas 233, fs. 13r and 13v. |

| 40 | As a peasant, it is completely expectable for Robles to be illiterate. Burke (2009, p. 251) has estimated that in early modern times, only approximately 20% of the European peasants could read and write, and that the probability of being illiterate increased among the Catholic peasants in Western Europe. |

| 41 | “Llegó a ella y habiéndose separado de su bienhechor con el reconocimiento debido, se fue a una posada pero sabido del sr presidente de aquella audiencia don Mateo Mata Ponce de León su paisano le mandó fuese a su casa donde le hizo albergar y mucho bien con grande atención y fineza a quien correspondió sumisamente comunicándole cuanto había caminado, visto, y reconocido en sus largas peregrinaciones, pareciéndose sería del servicio del rey, lo cual no había hecho con otro alguno”. AGI, Charcas 233, fs. 51r–51v. |

References

Archival Sources

AGI, Filipinas, 204, N.1. Consejo de Indias.(1702–1706: Expediente sobre el comercio entre Filipinas y Nueva España. Available online: http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/1931208?nm (accessed on 11 December 2021).AGI, Charcas 233. 1704. Declaración de Gregorio de Robles.AGI, Contratación 5448 N107. 1687. El capitán don Diego de Quiroga y Losada gobernador de la provincia de Florida.AGI, Indiferente 133 N187. 1702. Méritos Juan de Escobar Ayala.AGI, Contratación 5540A L3. 1690. Informaciones y Licencias de Pasajeros a Indias 1680–1690.AGI, Escribanía 580 B. 1691/1697. Testimonio de ramo de autos sacados sobre lo tocante a una negra que se declaro tocar y pertenecer al asiento de negros.AGNMe, Indiferente Virreinal, Caja 5001, Exp. 66. 1540. Traspaso de memoria en la que expone sus méritos el capitán Francisco de León, general en la región de la Frontera Chichimeca.AGS, EST, LEG, 3633, 191. 1693. Memorial de Manuel García de Bustamante, caballero de la Orden de Santiago y consejero del Consejo de Indias, solicitando el cargo de enviado extraordinario en Génova vacante por promoción de José de Haro.AHDTo, Dispensas matrimoniales, 1658a. Dispensa de Antonio Martin Soriano y Ursula Lopez vezinos de el Moral.AHDTo, Dispensas Matrimoniales, 1658b. Dispensa de Francisco de Castro y Margarita de Guertas—El Moral.AHNMa, OM-Caballeros_Calatrava, Exp.1838. 1715. Autos para las informaciones de Dn. Francisco Javier Ordoñez.AHNMa, Religiosos_Calatrava, Exp. 372. 1724. Expediente de pruebas de Antonio de la Canal de Aguilera Alguacil y de Cañizarez, natural de Moral, para el ingreso como religioso de la Orden de Calatrava.AHNMa, OM-Casamiento-Santiago, Apend. 573. 1 f. 1694. Expediente de pruebas de Isabel de Céspedes y Oviedo, natural de la villa de Moral de Calatrava, hija de Antonio de Céspedes y Oviedo y de Isabel de Cañizares, para contraer matrimonio con Agustín Ordóñez de Villaseñor, caballero de la orden de Santiago.AHPCR, Catastro del Marqués de Ensenada de 1750a. 1752–1754. Moral de Calatrava (La Mancha). Available online: https://www.familysearch.org/search/catalog/555673?availability=Family%20History%20Library (accessed on 17 December 2021).AHPCR, Catastro del Marqués de Ensenada de 1750b. 1752–1754. Moral de Calatrava (La Mancha). 720 Libro de Personal y de casas—eclesiástico.AHPCR, Catastro del Marqués de Ensenada de 1750c. 1752–1754. Moral de Calatrava (La Mancha). 717 bis Libro de personal secular y libro de casas secular.AHPCR, Ayuntamiento Local, La Solana 1679, La Solana 1, 119337, Exp. 6-1. 1679. Impreso, 2fs. Copia de la Real Provisión de Carlos II sobre diezmos de 1679.AHPCR, Protocolos Notariales; Fernando de Reinoso, 3.932, 1651–1659. Doña Josefa de Fuente Encalada, viuda de Don Francisco de Mena Valberde, sobre una casa (21 May 1653).AHNMa, Consejos, 35289, Exp. 26. 1722. Petición realizada por el concejo, justicia y regimiento de la villa de Valdepeñas y Moral de Calatrava.AHNMa, Inquisición, 50, Exp. 12. 1662. Pleito de competencias entre el Tribunal de la Inquisición de Toledo y el Consejo de las Ordenes. Available online: http://pares.mcu.es/ParesBusquedas20/catalogo/description/4592026?nm (accessed on 19 November 2021).Published Sources

- Albiez-Wieck, Sarah. 2017. Tributgesetzgebung und ihre Umsetzung in den Vizekönigreichen Peru und Neuspanien im Vergleich. Jahrbuch für Geschichte Lateinamerikas 54: 211–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arana, Luis, and Mark Johnson. 2021. The Military and Militia in Colonial Spanish America. St. Augustine: The Florida Department of Military Affairs, pp. 155–209. Available online: https://ufdc.ufl.edu/UF00047693/00001 (accessed on 10 November 2021).

- Barnert, Arno, and Andreas Schlüter. 2018. Stamped and Approved: The Travelling Books of Journeymen. The New Bookbinder 38: 65–71. [Google Scholar]

- Barrientos Grandon, Javier. 2022. García de Bustamante, Manuel. España, S. XVII–S. XVIII. Caballero de la Orden de Santiago, Consejero de Indias. Available online: https://dbe.rah.es/biografias/75307/manuel-garcia-de-bustamante (accessed on 21 January 2022).

- Benites, María J. 2013. Los Derroteros Teóricos de una Categoría Heterogénea: Los Relatos de Viajes al Nuevo Mundo (Siglo XVI). Moderna Sprak 1: 31–38. [Google Scholar]

- Brendecke, Arndt. 2009. Informing the Council: Central Institutions and Local Knowledge in the Spanish Empire. In Empowering Interactions: Political Cultures and the Emergence of the State in Europe, 1300–1900. Edited by Willem P. Blockmans, André Holenstein and Jon Mathieu. Farnham and Burlington: Ashgate, pp. 235–52. [Google Scholar]

- Burke, Peter. 2009. Popular Culture in Early Modern Europe, 3rd ed. Florence: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Campos y Fernández de Sevilla, Francisco Javier. 2004. Los Pueblos de Ciudad Real en las “Relaciones Topográficas” de Felipe II: Tomo I. Colección del Instituto Escurialense de Investigaciones Históricas y Artísticas 21. San Lorenzo del Escorial: Ediciones Escurialenses. [Google Scholar]

- Classen, Albrecht. 2018. Time, Space, and Travel in the Pre-Modern World: Theoretical and Historical Reflections. An Introduction. In Travel, Time, and Space in the Middle Ages and Early Modern Time: Explorations of World Perceptions and Processes of Identity Formation. Edited by Albrecht Classen. Fundamentals of Medieval and Early Modern Culture. Berlin and Boston: De Gruyter, vol. 22, pp. 1–75. [Google Scholar]

- Conrad, Sebastian. 2016. What Is Global History? Princeton: Princeton University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Corbin, Alain. 1999. Auf den Spuren eines Unbekannten: Ein Historiker Rekonstruiert ein ganz Gewöhnliches Leben. Frankfurt am Main and New York: Campus-Verlag. First published 1998. [Google Scholar]

- Craton, Michael. 1978. Searching for the Invisible Man: Slaves and Plantation Life in Jamaica. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, Natalie Zemon. 1983. The Return of Martin Guerre. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Donézar Díez de Ulzurrun, Javier. 1996. Riqueza y Propiedad en la Castilla del Antiguo Régimen: La Provincia de Toledo del Siglo XVIII. Madrid: Ministerio de Agricultura, Pesca y Alimentación. [Google Scholar]

- Fernández Llamazares, José. 1862. Historia Compendiada de las Cuatro Órdenes Militares de Santiago, Calatrava, Alcantara y Montesa. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2027/hvd.32044080120496 (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Fernández Moreno, Tomás. n.d. Gregorio de Robles Montes: Viajero, Explorador y Aventurero. Available online: https://www.esquinademauricio.es/wp-content/uploads/2019/04/a5.5.-Gregorio-de-Robles-Montes.pdf (accessed on 3 November 2021).

- Folger, Robert, and Larry J. Simon. 2011. Writing as Poaching: Interpellation and Self-Fashioning in Colonial Relaciones de Méritos y Servicios. The Medieval and Early Modern Iberian World v. 44. Leiden and Boston: Brill. [Google Scholar]

- Freitag, Ulrike. 2013. ‘Cosmopolitanism’ and ‘Conviviality’? Some Conceptual Considerations Concerning the Late Ottoman Empire. European Journal of Cultural Studies 17: 375–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García González, Francisco. 2021. Trayectorias Familiares: Reflexiones metodológicas para la investigación en el Antiguo Régimen. In Familias, Trayectorias y Desigualdades: Estudios de Historia Social en España y en Europa, Siglos XVI–XIX. Edited by Francisco García González. Madrid: Sílex, pp. 27–54. [Google Scholar]

- García González, Francisco, and Cosme J. Gómez Carrasco. 2010. Tierra y Sociedad Rural en Castilla-La Mancha a Finales del Antiguo Régimen. In Historia Agraria de Castilla-La Mancha: Siglos XIX–XXI. Biblioteca Añil 48. Edited by Ángel Ramón del Valle Calzado. Ciudad Real: Almud, pp. 83–116. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Andrés, Carlos. 2010. Piedralén: Historia de un Campesino; de Cuba a la Guerra Civil. Madrid: Marcial Pons. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Montero, Raquel. 2020. Las categorías fiscales del siglo XVII en Charcas (actual Bolivia) frente al desafío de las migraciones y el mestizaje. In El que no Tiene de Inga, Tiene de Mandinga. Honor y Mestizaje en los Mundos Americanos. Edited by Sarah Albiez-Wieck, Lina M. Cruz Lira and Antonio Fuentes Barragán. Madrid and Frankfurt am Main: Iberoamericana Vervuert, pp. 79–110. [Google Scholar]

- Gil Montero, Raquel. 2021. A Case for a History of Ordinary Lives. Histories 1: 3–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gil Montero, Raquel, and Sarah Albiez-Wieck. 2019. Conviviality as a Tool for Creating Networks: The Case of an Early Modern Global Peasant Traveller. Mecila Working Paper Series No. 19. Available online: http://mecila.net/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/WP-19-Gil-Montero-and-Albiez-Wieck-Online-Final.pdf (accessed on 2 September 2019).

- Gillaspie, William R. 1968. Sergeant Major Ayala y Escobar and the Threatened St. Augustine Mutiny. The Florida Historical Quarterly 47: 151–64. [Google Scholar]

- Ginzburg, Carlo. 1990. Der Käse und die Würmer: Die Welt eines Müllers um 1600. Wagenbachs Taschenbuch 178. Berlin: Wagenbach. First published 1976. [Google Scholar]

- González, Alfonso. 1971. The Population of Cuba. Caribbean Studies 11: 74–84. [Google Scholar]

- Herzog, Tamar. 2003. Defining Nations: Immigrants and Citizens in Early Modern Spain and Spanish America. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Imbernón, José-María. 1986. La Real Audiencia de Quito: Reflexiones en Torno al Contrabando Colonial. Revista Mexicana de Sociología 48: 87–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keller, Andreas, and Winfried Siebers. 2017. Einführung in die Reiseliteratur. Germanistik Kompakt. Edited by Klaus-Michael Bogdal and Gunter E. Grimm. Darmstadt: WBG (Wissenschaftliche Buchgesellschaft), p. 24. [Google Scholar]

- Klein, Herbert S. 1966. The Colored Militia of Cuba: 1568–1868. Caribbean Studies 6: 17–27. [Google Scholar]

- Lafuente, Modesto, and Juan Valera. 1889. Historia General de España: Desde los Tiempos Primitivos Hasta la Muerte de Fernando VII. Tomo XII. Barcelona: Montaner y Simon Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Lindsay, Claire. 2019. Hispanic Travel Writing. In The Cambridge History of Travel Writing. Edited by Nandinia Das and Tim Youngs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- López-Salazar Pérez, Jerónimo. 1986. Estructuras Agrarias y Sociedad Rural en La Mancha: SS. XVI–XVII. Ciudad Real: Instituto de Estudios Manchegos. [Google Scholar]

- MacLean, Gerald. 2019. Early Modern Travel Writing (1): Print and Early Modern European Travel Writing. In The Cambridge History of Travel Writing. Edited by Nandinia Das and Tim Youngs. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Marchena Fernández, Juan. 1985. Las Levas de Soldados a Indias en la Baja Andalucía: Siglo XVII. In Andalucía y América en el Siglo XVII. Actas de las III Jornadas de Andalucía y América. Edited by Bibiano Torres Ramírez and José J. Hernández. Palomo. Palos de la Frontera: Universidad de Santa María de la Rábida, vol. 1, pp. 93–118. [Google Scholar]

- Marchena Fernández, Juan. 2019. Pugnas comerciales y familiares en el juego de los intercambios en el Caribe. Los comerciantes portugueses 1580–1640. Americanía Revista de Estudios Latinoamericanos 9: 36–90. [Google Scholar]

- Maria Sibylla Merian International Centre for Advanced Studies in the Humanities, and Social Sciences Conviviality-Inequality in Latin America. 2019. Conviviality in Unequal Societies: Perspectives from Latin America. Thematic Scope and Preliminary Research Programme. Mecila Working Paper Series. Available online: https://mecila.net/wp-content/uploads/2020/11/WP_1_Thematic_Scope_and_Research_Programme.pdf (accessed on 17 June 2019).

- Martinic, Mateo B. 2016. Bucaneros en el Estrecho de Magallanes Durante la Segunda Mitad del Siglo XVII, Nuevos Antecedentes. Magallania (Punta Arenas) 44: 5–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Mathieu, Jon. 2021. A Case for Global Microhistory. Histories 1: 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniketti, Marco. 2006. Sugar Mills, Technology, and Environmental Change: A Case Study of Colonial AgroIndustrial Development in the Caribbean. The Journal of the Society for Industrial Archeology 32: 53–80. [Google Scholar]

- Moreno Fraginals, Manuel. 1995. Cuba/España. España/Cuba: Historia Común. Barcelona: Crítica. [Google Scholar]

- Moutoukias, Zacarías. 1996. Negocios y Redes Sociales: Modelo Interpretativo a Partir de un Caso Rioplatense (Siglo XVIII). Cahiers du Monde Hispanique et Luso-Brésilien 67: 37–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mulcahy, Matthew. 2008. The Port Royal Earthquake and the World of Wonders in Seventeenth-Century Jamaica. Early American Studies 6: 391–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nowicka, Magdalena, and Steven Vertovec. 2014. Comparing Convivialities: Dreams and Realities of Living-with-Difference. European Journal of Cultural Studies 17: 341–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orr, Julie M. 2014. New Caledonia’s Wake: Expanding the Story of Company of Scotland Expeditions to Darien, 1698–1700. Ph.D. thesis, University of Dundee, Dundee, UK. [Google Scholar]

- Pietschmann, Horst. 1980. Die Staatliche Organisation des Kolonialen Iberoamerika. Handbuch der Lateinamerikanischen Geschichte, Teilveröffentlichung. Stuttgart: Klett-Cotta. [Google Scholar]

- Pollmann, Judith, and Ericka Kujpers. 2015. Introduction: On the Early Modernity of Modern Memory. In Memory Before Modernity: Practices of Memory in Early Modern Europe. Edited by Erika Kuijpers. Studies in Medieval and Reformation Traditions v. 176. Leiden and Boston: Brill, pp. 1–26. [Google Scholar]

- Poska, Allyson M. 2005. Women and Authority in Early Modern Spain. The Peasants of Galicia. Oxford: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Postigo Castellanos, Elena. 1988. Honor y Privilegio en la Corona de Castilla: El Consejo de las Ordenes y los Caballeros de Hábito en el S. XVII. Almazàn: Junta de Castilla y Leon. [Google Scholar]

- Pratt, Mary L. 2008. Imperial Eyes: Travel Writing and Transculturation. London and New York: Routledge. First published 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, Casey. 2019. Centering Spanish Jamaica: Regional Competition, Informal Trade, and the English Invasion, 1620–1662. The William and Mary Quarterly 76: 697–726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sociedad Geográfica Española. 2009. Atlas de los Exploradores Españoles. Barcelona: GeoPlaneta. [Google Scholar]

- Subrahmanyam, Sanjay. 2007. Holding the World in Balance: The Connected Histories of the Iberian Overseas Empires, 1500–1640. The American Historical Review 112: 1359–85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tau Anzóategui, Víctor, ed. 1980. Gregorio de Robles. América a Fines del Siglo XVII: Noticia de los Lugares de Contrabando. Edición Especial con Ocasión del VI Congreso del Instituto Internacional de Historia del Derecho Indiano. Serie Americanista 14. Presentación de Demetrio Ramos Pérez, Introducción de Víctor Tau Anzóategui. Valladolid: Casa-Museo de Colón y Seminario Americanista de la Universidad de Valladolid. [Google Scholar]

- Torre Revello, José. 1930. Un Trotamundos Español de Fines del Siglo XVII. Síntesis 34: 49–64. [Google Scholar]

- Trevor-Roper, Hugh. 2009. La Crisis del Siglo XVII: Religión, Reforma y Cambio Social, 1st ed. Katz Conocimiento. Buenos Aires and Madrid: Katz Editores. [Google Scholar]

- Trivellato, Francesca. 2011. Is There a Future for Italian Microhistory in the Age of Global History? California Italian Studies, 2. Available online: https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0z94n9hq (accessed on 14 March 2022). [CrossRef]

- Unidad de Promoción y Desarrollo de la Excma. Diputación de Ciudad Real. 2021. Estudio Socioeconómico del Campo de Calatrava Histórico: Moral de Calatrava. Available online: https://www.google.com/url?sa=t&rct=j&q=&esrc=s&source=web&cd=&cad=rja&uact=8&ved=2ahUKEwiWh7PNlYn0AhWnhf0HHasZDwsQFnoECAIQAQ&url=http%3A%2F%2Fwww.campodecalatrava.com%2Fcec%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2FMoral.pdf&usg=AOvVaw2qRNZVhaLbwNrvH5Wq6z3J (accessed on 8 November 2021).

- Vassberg, David E. 1984. Land and Society in Golden Age Castile. Cambridge Iberian and Latin American Studies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Vries, Jan. 1976. Economy of Europe in an Age of Crisis, 1600–1750. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Wiesner, Merry E. 1991. ‘Wandervogels’ Women: Journeymen’s Concepts of Masculinity in Early Modern Germany. Journal of Social History 24: 767–82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Albiez-Wieck, S.; Gil Montero, R. A Needle in a Haystack: Looking for an Early Modern Peasant Who Travelled from Spain to America. Histories 2022, 2, 91-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2020009

Albiez-Wieck S, Gil Montero R. A Needle in a Haystack: Looking for an Early Modern Peasant Who Travelled from Spain to America. Histories. 2022; 2(2):91-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2020009

Chicago/Turabian StyleAlbiez-Wieck, Sarah, and Raquel Gil Montero. 2022. "A Needle in a Haystack: Looking for an Early Modern Peasant Who Travelled from Spain to America" Histories 2, no. 2: 91-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2020009

APA StyleAlbiez-Wieck, S., & Gil Montero, R. (2022). A Needle in a Haystack: Looking for an Early Modern Peasant Who Travelled from Spain to America. Histories, 2(2), 91-111. https://doi.org/10.3390/histories2020009