Perspectives on Building Sustainable Newborn Screening Programs for Sickle Cell Disease: Experience from Tanzania

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

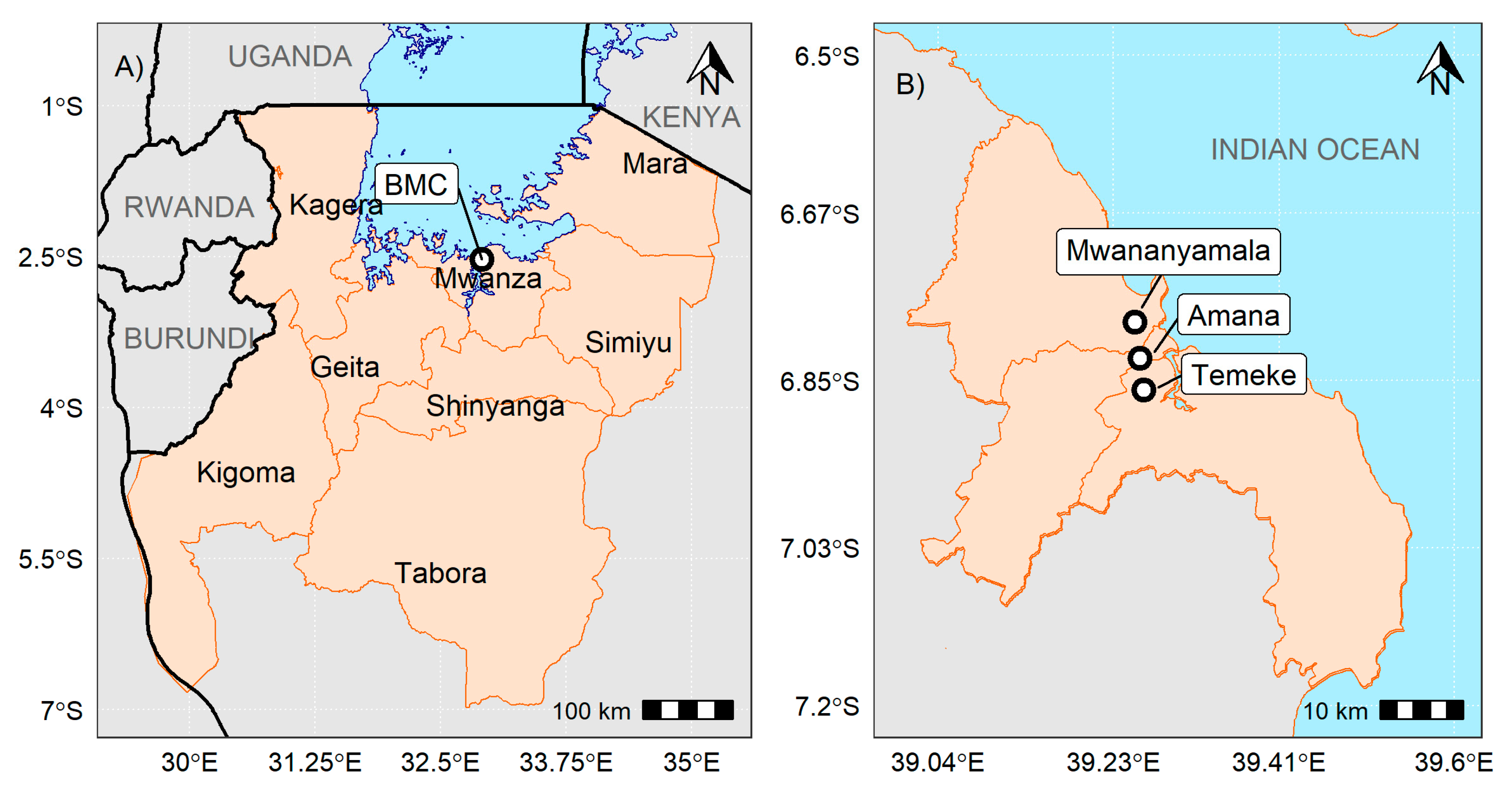

2.1. Study Settings

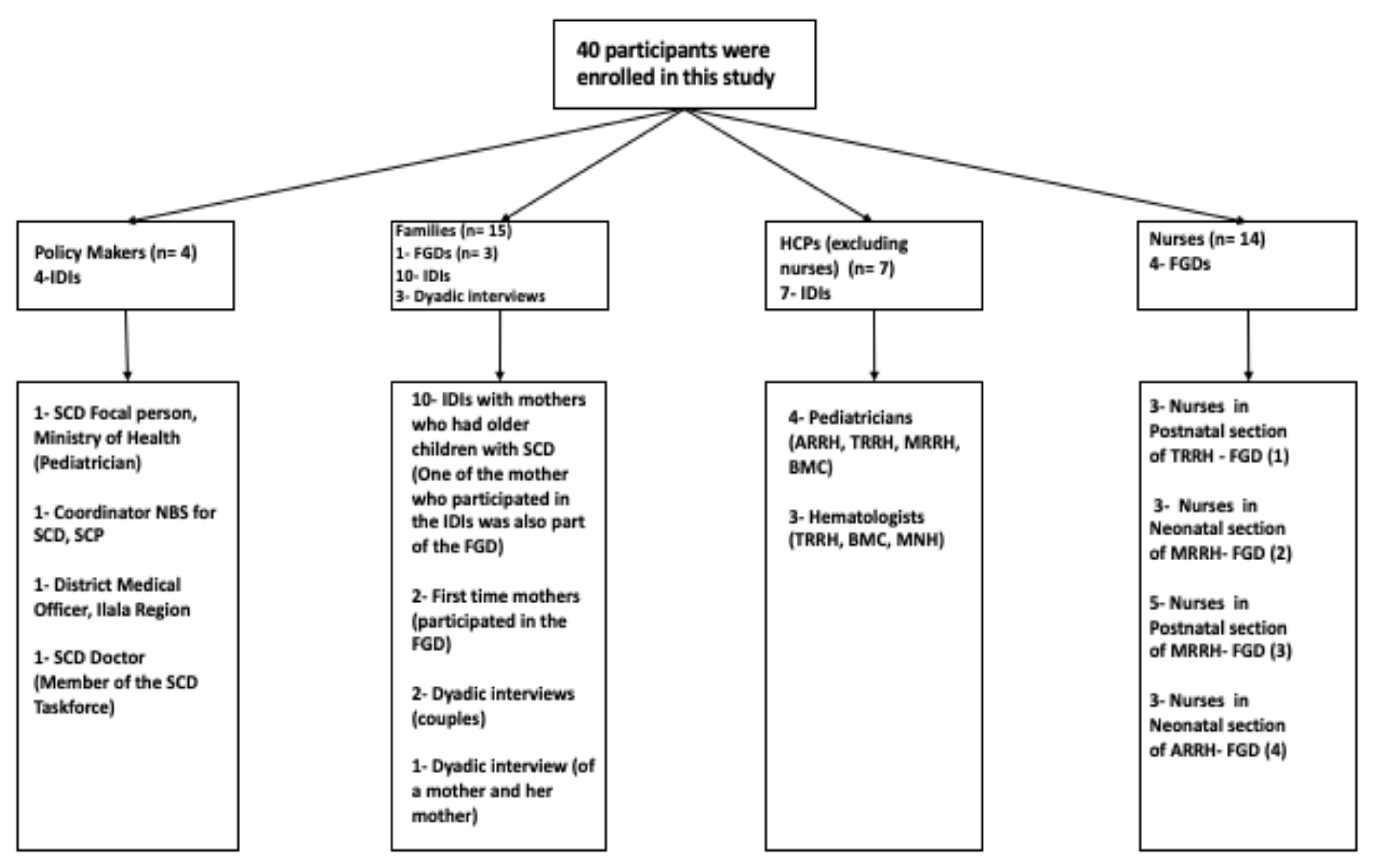

2.2. Study Population

2.3. Data Collection Methods

2.4. Data Analysis

3. Results

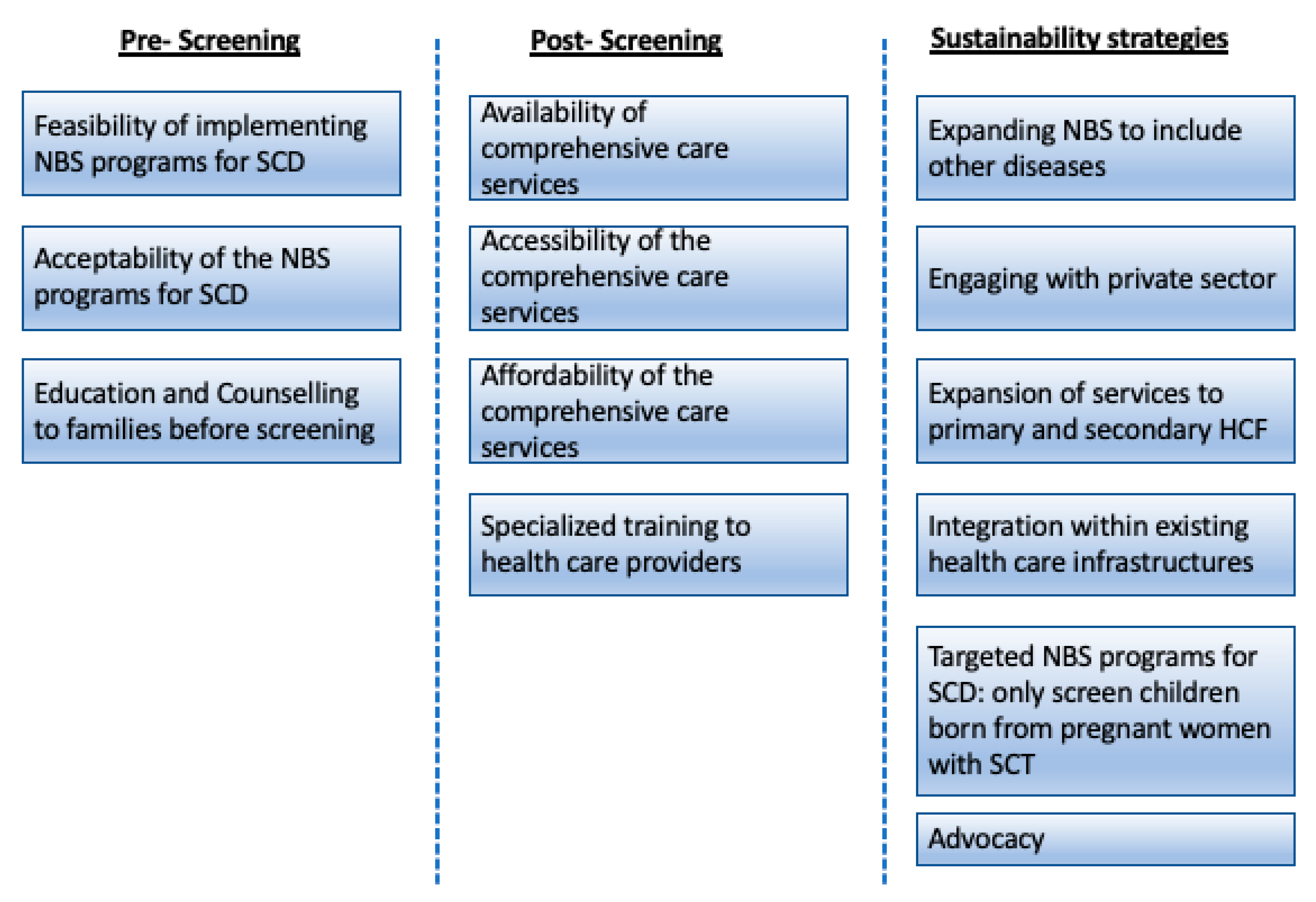

3.1. Pre-Screening

3.1.1. Feasibility of Conducting NBS for SCD

“We have also talked about policy makers and how we can take them on board to ensure newborn screening for sickle cell disease is prioritized. If we succeed in doing that then all the activities will be budgeted by the Ministry of Health [NBS for SCD], having its own budget it will be easy for the implementers. Also, the hospital will need to have qualified personnel who are knowledgeable about the program to provide education to the families. The same with Laboratory diagnostics and other interventions. Since hematologists are very few in Tanzania, we will have to encourage our doctors to pursue those trainings and our nurses to fully implement the programs” 1_IDI_Implementers_Paediatrician_MRRH_06.08.18.

3.1.2. Acceptability of NBS for SCD

“From our experiences of screening these children for sickle cell disease, we never had a situation where mothers will refuse to screen their babies for whatever reasons. Most of them are happy to get their children screened. We never had refusal based on certain culture [or tribe] not allowing newborn babies to be screened” 1-FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Postnatal Unit_TRRH_07.08.18.

“Mothers may find it hard to accept because of the little understanding they have about the disease, but when you educate them then it is easy to accept screening their children. So, her own understanding will influence her to screen the child. We also tell the mothers the benefits of knowing early if your child is born with the disease” 2_FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Neonatal Unit_ARRH_27.08.18.

“For me when I gave birth, the nurse came and advise us or may be requested us to screen our children for sickle cell disease, and she asked us, are you ready? and because I know this problem is there [in her family] I was also attracted to screen my child for sickle cell, and I say okay I am ready. They took the blood, and they promise to call us to give us the result back” 5_IDI_Families_both parents_30.01.2019.

3.1.3. Education and Counselling to Families

“Education to nurses is needed for them to provide counselling to the families. It is difficult to counsel or educate another person if you don’t have enough knowledge of the disease” 7_IDI_Implementers_Haematologist_TRRH_14.09.18

“However, the education provided was a small bit of everything, we are educated not only about sickle cell even how to breastfeed our babies. Therefore, we did not think of even asking questions on sickle cell- M1 (Probe: so, when do you think is the right time to provide the education) Education has to start in the antenatal clinics, because the day when we gave birth, the mother is being told so many things, you cannot remember everything” 1_FGD_Families_TRRH_01.09.18.

3.2. Post-Screening

3.2.1. Availability of Comprehensive Care Services

“The most challenging aspect is diagnostic tests, but sickle cell clinics have been there in some of the regional referral hospitals, and we do have data in terms of the number of patients visiting those clinics for over the years” 1-IDI_Policy makers_ Coordinator of SCD programs, Ministry of Health_20.08.2018.

3.2.2. Accessibility of Comprehensive Care Services

“It is also important to do follow ups with patients if they are not attending clinics, but if we just wait for patients to come to the clinic [without follow ups] then there are many patients who cannot come to clinics because they don’t have money for transport. The child may be sick, and they will not be able to bring them to the hospital. Temeke is so big people are coming from different places and if all the children will have to come to Temeke, it is not going to be possible” 1-FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Postnatal Unit_TRRH_07.08.18.

3.2.3. Affordability of the Health Care Services

“[P1] The government policy require children with chronic illness to access care for free, so for pediatric sickle cell clinic, drugs are given for free. I am not sure if Penicillin is available [they might be asked to go and buy) but folic acid is given for free. [P2] We encourage families to buy insurance for their children, most parents believe that if you have children under five then everything is free, but it is not everything, insurance will be able to pay so many things” 4_FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Neonatal Unit_MRRH_09.08.18.

“With regard to the services, we just need to have the health insurance, for those who don’t have insurance they are getting so many difficulties, for example the other day when I came to the clinic, that thing for taking out blood [Cannula?], I was told to go and buy it, sometime there are no drugs you have to pay out of pocket, so those are some of the challenges. Some families don’t have money to pay for the services or buy the insurance. The only solution is for sickle cell patients to be treated for free” 11_IDI_Families_15.02.2019.

3.2.4. Training for Health Care Professionals (HCPs)

“Training are still needed, on our side [nurses] we need to be trained before we start educating families. If we are knowledgeable about the disease, the benefits of screening and the management options available, then it will be easy to educate the families” 3_FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Postnatal Unit_MRRH_09.08.18.

“Since this service is new then, the nurses will need refresher training for those who will be responsible for running the programs. And also we should not select one or two people to get the training, because other staff will wait until that person is around to do the work [the program become this person project] or telling the families come another day the [nurse] is not around. So if it will include postnatal unit then all the nurses need to be trained [how to screen, how to transport the sample and the diagnostic aspect] it has to be integrated with the hospital structure. If you use one or two person you will need to pay them and that will bring segregation amongst the staff” 5_IDI_Implementers_Paediatrician_TRRH_13.08.18.

3.3. Proposed Sustainability Strategies That may Be Applicable to Low Resources Settings

3.3.1. Expanding NBS to Include other Diseases

“Expanding the screening services will give us an opportunity to do so many tests under one umbrella, so the same DBS samples can be used to screen other diseases such as HIV. Now, the question is do we have the resources to do all the tests? but as a recommendation I think we should think of it [expanding] the issues of resources will come after we are ready. The primary aim is to benefit the child” IDI_DMO_Ilala_Policymaker_20.08.18.

“This needs to be advocated to the ministry [expanding NBS programs] to involve other diseases as a way of minimizing the costs for screening instead of just screening for one disease. Although this feels like a very long-term plan” 2_FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Neonatal Unit_ARRH_27.08.18.

“We did a pilot program to screen all newborn babies for sickle cell disease born in Bugando hospital centers but due to issues of reagents we had to stop. And we did start another program to screen only a small population of children born with exposed mothers [children who were less than 24 months] since all the DBS are coming to our hospitals from all regions, we thought this is a very good platform to screen for Sickle Cell Disease. We have completed this project three weeks ago, and I can say the prevalence is still very high” 3_IDI_Implementers_Paediatrician_BMC_15.08.18.

3.3.2. Engaging with the Private Sector

“At the ministry of health, we have a section that only deals with public private partnership and also another section that deals with private health facilities and also diagnostic service department. Through those resources we can assess in what ways we can benefit from each other especially in the area of diagnosis. We are aware that private health facilities are doing a number of screening, so yes there is a lot that we can learn and leverage from each other” 2_IDI_MoHGEC_Policy Maker_01.08.18.

3.3.3. Expansion of Services to Primary and Secondary Health Facilities (HF)

“We are hoping for the best on the newborn screening for Sickle Cell Disease, whatever we are doing there [in the referral hospitals] can also be done in primary and secondary health facilities. We can start piloting the programs in regional referral hospitals like Temeke, it is still possible to collect DBS in primary as well as secondary health facilities with much higher number of births. Sample can be collected daily and processed in a centralized laboratory [Muhimbili] Nurses that have been trained here in Temeke can train other nurses in the health facilities” 5_IDI_Implementers_Paediatrician_TRRH_13.08.18.

3.3.4. Integration within Existing Health Care Infrastructures

“If we want these services [NBS for SCD] to be sustainable it has to be part of the hospital plans, it has to be one of the services offered in the hospital and not a funded program that when the donors leave then the project is not there. If it will be part of the hospital services, then it can be sustained even at a lowest scale possible. This means when the hospital is doing budgeting if there are any reagents or laboratory diagnostics then will be budgeted” 2_FGD_Implementers_Nurses_Neonatal Unit_ARRH_27.08.18.

3.3.5. Targeted NBS Programs for SCD: Only Screen children Born from Pregnant Women with Sickle Cell Trait (SCT)

“Families were mothers will be identified to have sickle cell trait, then the children will have to be screened. The antenatal cards can be used to capture this information [this is within our ability] On my side I will take this forward and start implementing” 1_IDI_DMO_Ilala_Policymaker_20.08.18.

3.3.6. Advocacy

“We are doing advocacy campaigns targeting the community as well as the decision makers [government officials, policy makers]. For example, the school campaigns program that we are currently involved to build awareness amongst secondary school children. With regard to the government and Ministry, we are trying to provide evidence on how big this problem is and what are the possible solutions. We do believe with continuous advocacy we can achieve our goals” Member of the SCD taskforce, Ministry of Health.

“So again, that’s a policy issue and I think that’s why for me it’s almost impossible to talk about anything in isolation because we need multiple initiatives at the same time. So, while we are doing NBS we are also supposed to be talking to the Government about what we are doing [through providing evidence], our role should be advising—for what works and what doesn’t. If it has to be sustainable at some point, we need to see the Government owning the program. So how can that be? I think it’s going to be a very slow process; the most important thing is we are going in that direction” IDI_Implementers _NBS for SCD Coordinator_Sickle Cell Program_07.022019.

4. Discussion

4.1. Pre-Screening

4.2. Post Screening

4.3. Sustainability Strategies

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Chima, C.C.; Homedes, N. Impact of global health governance on country health systems: The case of HIV initiatives in Nigeria. J. Glob. Health 2015, 5, 010407. [Google Scholar]

- Cernuschi, T.; Gaglione, S.; Bozzani, F. Challenges to sustainable immunization systems in Gavi transitioning countries. Vaccine 2018, 36, 6858–6866. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moseley, S.F. Sustainability for development programmes. Development 2011, 54, 161–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.D.; Therrell, B.L. Consolidating newborn screening efforts in the Asia Pacific region: Networking and shared education. J. Community Genet. 2012, 3, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bennett, S.; Singh, S.; Ozawa, S.; Tran, N.; Kang, J.S. Sustainability of donor programs: Evaluating and informing the transition of a large HIV prevention program in India to local ownership. Glob. Health Action 2011, 4, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, D.; Clinton, C. Governing Global Health; United States of America by Oxford University Press: New York, NY, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Mihigo, R.; Okeibunor, J.; Cernuschi, T.; Petu, A.; Satoulou, A.; Zawaira, F. Improving access to affordable vaccines for middle-income countries in the african region. Vaccine 2019, 37, 2838–2842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piel, F.B.; Patil, A.P.; Howes, R.E.; Nyangiri, O.A.; Gething, P.W.; Dewi, M.; Temperley, W.H.; Williams, T.N.; Weatherall, D.J.; Hay, S.I. Global epidemiology of sickle haemoglobin in neonates: A contemporary geostatistical model-based map and population estimates. Lancet 2013, 381, 142–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Makani, J.; Cox, S.E.; Soka, D.; Komba, A.N.; Oruo, J.; Mwamtemi, H.; Magesa, P.; Rwezaula, S.; Meda, E.; Mgaya, J.; et al. Mortality in sickle cell anemia in africa: A prospective cohort study in Tanzania. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e14699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- King, L.G.C.; Bortolusso-Ali, S.; Cunningham-Myrie, C.A.; Reid, M.E.G. Impact of a Comprehensive Sickle Cell Center on Early Childhood Mortality in a Developing Country: The Jamaican Experience. J. Pediatr. 2015, 167, 702–705.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene-frempong, K.; Bonney, A.; Tetteh, H.; Nkrumah, F.K. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in ghana: 270. Pediatr. Res. 2005, 58, 401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tshilolo, L.; Kafando, E.; Sawadogo, M.; Cotton, F.; Vertongen, F.; Ferster, A.; Gulbis, B. Neonatal screening and clinical care programmes for sickle cell disorders in sub-Saharan Africa: Lessons from pilot studies. Public Health 2008, 122, 933–941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, P.; Ferris, M.; Macosso, P.; de Oliveira, V.; Ramamurthy, U.; Luis, A. A prospective pilot newborn screening and treatment program for sickle cell anemia in the Republic of Angola. Blood 2012, 120, 480. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tubman, V.N.; Marshall, R.; Jallah, W.; Guo, D.; Ma, C.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; London, W.B.; Heeney, M.M. Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Liberia: A Pilot Study. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2016, 63, 671–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Green, N.S.; Mathur, S.; Kiguli, S.; Makani, J.; Fashakin, V.; LaRussa, P.; Lyimo, M.; Abrams, E.J.; Mulumba, L.; Mupere, E. Family, Community, and Health System Considerations for Reducing the Burden of Pediatric Sickle Cell Disease in Uganda Through Newborn Screening. Glob. Pediatr. Health 2016, 3, 2333794X1663776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nkya, S.; Mtei, L.; Soka, D.; Mdai, V.; Mwakale, P.B.; Mrosso, P.; Mchoropa, I.; Rwezaula, S.; Azayo, M.; Ulenga, N.; et al. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease: An innovative pilot program to improve child survival in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Int. Health 2019, 11, 589–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odunvbun, M.E.; Okolo, A.A.; Rahimy, C.M. Newborn screening for sickle cell disease in a Nigerian hospital. Public Health 2008, 122, 1111–1116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuznik, A.; Habib, A.G.; Munube, D.; Lamorde, M. Newborn screening and prophylactic interventions for sickle cell disease in 47 countries in sub-Saharan Africa: A cost-effectiveness analysis. BMC Health Serv. Res. 2016, 16, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, L.; Nnodu, O.E.; Brown, B.J.; Tluway, F.; King, S.; Dogara, L.G.; Patil, C.; Shevkoplyas, S.S.; Lettre, G.; Cooper, R.S.; et al. White Paper: Pathways to Progress in Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Sub-Saharan Africa. J. Trop. Dis. 2018, 6, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ohene-Frempong, K.; Oduro, J.; Tetteh, H.; Nkrumah, F. Screening newborns for sickle cell disease in ghana: Table 1. Pediatrics 2008, 121, S120–S121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrell, B.L.; Lloyd-Puryear, M.A.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Ware, R.E.; Padilla, C.D.; Ambrose, E.E.; Barkat, A.; Ghazal, H.; Kiyaga, C.; Mvalo, T.; et al. Empowering newborn screening programs in African countries through establishment of an international collaborative effort. J. Community Genet. 2020, 11, 253–268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnodu, O.; Isa, H.; Nwegbu, M.; Ohiaeri, C.; Adegoke, S.; Chianumba, R.; Ugwu, N.; Brown, B.; Olaniyi, J.; Okocha, E.; et al. HemoTypeSC, a low-cost point-of-care testing device for sickle cell disease: Promises and challenges. Blood Cells Mol. Dis. 2019, 78, 22–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tluway, F.; Makani, J. Sickle cell disease in Africa: An overview of the integrated approach to health, research, education and advocacy in Tanzania, 2004–2016. Br. J. Haematol. 2017, 177, 919–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saidi, H.; Smart, L.R.; Kamugisha, E.; Ambrose, E.E.; Soka, D.; Peck, R.N.; Makani, J. Complications of sickle cell anaemia in children in Northwestern Tanzania. Hematology 2016, 21, 248–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, E.E.; Smart, L.R.; Charles, M.; Hernandez, A.G.; Hokororo, A.; Latham, T.; Beyanga, M.; Tebuka, E.; Kamugisha, E.; Howard, T.A.; et al. Geospatial Mapping of Sickle Cell Disease in Northwest Tanzania: The Tanzania Sickle Surveillance Study (TS3). Blood 2018, 132, 3662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bukini, D.; Mbekenga, C.; Nkya, S.; Malasa, L.; McCurdy, S.; Manji, K.; Parker, M.; Makani, J. Influence of gender norms in relation to child’s quality of care: Follow up of families of children with Sickle Cell Disease identified through new-born screening in Tanzania. J. Community Genet. 2020, 98, 859. [Google Scholar]

- Tong, A.; Sainsbury, P.; Craig, J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): A 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int. J. Qual. Heal. Care 2007, 19, 349–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ward, D.J.; Furber, C.; Tierney, S.; Swallow, V. Using Framework Analysis in nursing research: A worked example. J. Adv. Nurs. 2013, 69, 2423–2431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gale, N.K.; Heath, G.; Cameron, E.; Rashid, S.; Redwood, S. Using the framework method for the analysis of qualitative data in multi-disciplinary health research. BMC Med. Res. Methodol. 2013, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waiswa, P.; Kemigisa, M.; Kiguli, J.; Naikoba, S.; Pariyo, G.W.; Peterson, S. Acceptability of evidence-based neonatal care practices in rural Uganda-Implications for programming. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2008, 8, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Becker-Dreps, S.; Otieno, W.A.; Brewer, N.T.; Agot, K.; Smith, J.S. HPV vaccine acceptability among Kenyan women. Vaccine 2010, 28, 4864–4867. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nzewi, E. Malevolent Ogbanje: Recurrent Reincarnation or Sickle Cell Disease? Soc. Sci. Med. 2001, 52, 1403–1416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daak, A.A.; Elsamani, E.; Ali, E.H.; Mohamed, F.A.; Abdel-Rahman, M.E.; Elderdery, A.Y.; Talbot, O.; Kraft, P.; Ghebremeskel, K.; Elbashir, M.I.; et al. Sickle cell disease in western Sudan: Genetic epidemiology and predictors of knowledge attitude and practices. Trop. Med. Int. Health 2016, 21, 642–653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Antwi, J.A.; Culley, L.; Hiles, D.R.; Dyson, S.M. “I can die today, i can die tomorrow”: Lay perceptions of sickle cell disease in Kumasi, Ghana at a point of transition. Ethn. Heal. 2011, 16, 465–481. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis-Antwi, J.A.; Ohene-Frempong, K.; Anie, K.A.; Dzikunu, H.; Agyare, V.A.; Boadu, R.O.; Antwi, J.S.; Asafo, M.K.; Anim-Boamah, O.; Asubonteng, A.K.; et al. Relation Between Religious Perspectives and Views on Sickle Cell Disease Research and Associated Public Health Interventions in Ghana. J. Genet. Couns. 2018, 28, 102–118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marsh, V.M.; Kamuya, D.M.; Molyneux, S.S. “All her children are born that way”: Gendered experiences of stigma in families affected by sickle cell disorder in rural Kenya. Ethn. Health 2011, 16, 343–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nnodu, O.E.; Adegoke, S.A.; Ezenwosu, O.U.; Emodi, I.I.; Ugwu, N.I.; Ohiaeri, C.N.; Brown, B.J.; Olaniyi, J.A.; Isa, H.; Okeke, C.C.; et al. A Multi-centre Survey of Acceptability of Newborn Screening for Sickle Cell Disease in Nigeria. Cureus 2018, 10, e2354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Vries, J.; Landouré, G.; Wonkam, A. Stigma in African genomics research: Gendered blame, polygamy, ancestry and disease causal beliefs impact on the risk of harm. Soc. Sci. Med. 2020, 258, 113091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ambrose, E.E.; Makani, J.; Chami, N.; Masoza, T.; Kabyemera, R.; Peck, R.N.; Kamugisha, E.; Manjurano, A.; Kayange, N.; Smart, L.R. High birth prevalence of sickle cell disease in Northwestern Tanzania. Pediatr. Blood Cancer 2018, 65, e26735. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, P.; Santos, B.; de Oliveira, V.; Bernadino, L.; Ware, R.E.; Grosse, D. Cost-effectiveness of neonatal screening for sickle cell disease in the Republic of Angola. Blood 2013, 122, 421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.; Sinski, A.; Asibey, J.; Hardy-Dessources, M.D.; Elana, G.; Brennan, C.; Odame, I.; Hoppe, C.; Geisberg, M.; Serrao, E.; et al. Point-of-care screening for sickle cell disease in low-resource settings: A multi-center evaluation of HemoTypeSC, a novel rapid test. Am. J. Hematol. 2019, 94, 39–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nnodu, O.E.; Sopekan, A.; Nnebe-Agumadu, U.; Ohiaeri, C.; Adeniran, A.; Shedul, G.; Isa, H.A.; Owolabi, O.; Chianumba, R.I.; Tanko, Y.; et al. Implementing newborn screening for sickle cell disease as part of immunisation programmes in Nigeria: A feasibility study. Lancet Haematol. 2020, 7, e534–e540. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Padilla, C.D.; Krotoski, D. Newborn Screening Progress in Developing Countries—Overcoming Internal Barriers. Semin. Perinatol. 2010, 34, 145–155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Howson, C.P.; Cedergren, B.; Giugliani, R.; Huhtinen, P.; Padilla, C.D.; Palubiak, C.S.; Santos, M.D.; Schwartz, I.V.D.; Therrell, B.L.; Umemoto, A.; et al. Universal newborn screening: A roadmap for action. Mol. Genet. Metab. 2018, 124, 177–183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Therrell, B.L.; Padilla, C.D. Barrier to Implementing. Int. J. Pediatr. Adolesc. Med. 2014, 1, 49–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odendaal, W.A.; Ward, K.; Uneke, J.; Uro-Chukwu, H.; Chitama, D.; Balakrishna, Y.; Kredo, T. Contracting out to improve the use of clinical health services and health outcomes in low- and middle-income countries. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2018, 4, CD008133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iliff, A.R.; Jha, A.K. Public–Private Partnerships in Global Health—Driving Health Improvements without Compromising Values. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 380, 1097–1099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McGann, P.T. Improving survival for children with sickle cell disease: Newborn screening is only the first step. Paediatr. Int. Child Health 2015, 35, 285–286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Bukini, D.; Nkya, S.; McCurdy, S.; Mbekenga, C.; Manji, K.; Parker, M.; Makani, J. Perspectives on Building Sustainable Newborn Screening Programs for Sickle Cell Disease: Experience from Tanzania. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2021, 7, 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7010012

Bukini D, Nkya S, McCurdy S, Mbekenga C, Manji K, Parker M, Makani J. Perspectives on Building Sustainable Newborn Screening Programs for Sickle Cell Disease: Experience from Tanzania. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2021; 7(1):12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7010012

Chicago/Turabian StyleBukini, Daima, Siana Nkya, Sheryl McCurdy, Columba Mbekenga, Karim Manji, Michael Parker, and Julie Makani. 2021. "Perspectives on Building Sustainable Newborn Screening Programs for Sickle Cell Disease: Experience from Tanzania" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 7, no. 1: 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7010012

APA StyleBukini, D., Nkya, S., McCurdy, S., Mbekenga, C., Manji, K., Parker, M., & Makani, J. (2021). Perspectives on Building Sustainable Newborn Screening Programs for Sickle Cell Disease: Experience from Tanzania. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 7(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns7010012