Historical Appreciation of World Health Organization’s Public Health Paper-34: Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, by Max Wilson and Gunnar Jungner

Abstract

1. Introduction

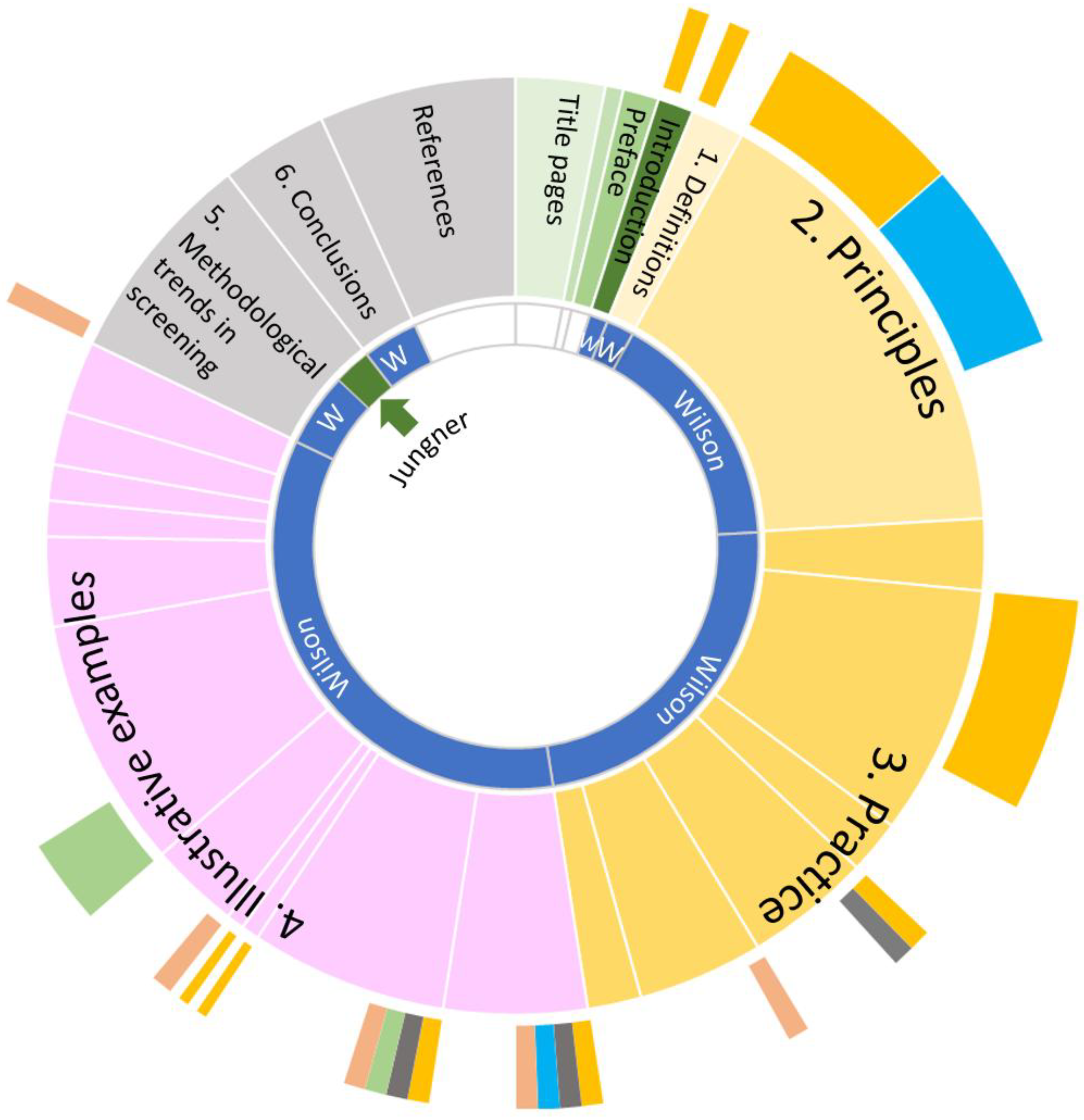

2. Background to Quantitative Analysis of PHP-34

3. Quantitative Analysis of PHP-34

3.1. A Quantitative Analysis of PHP-34—Introduction to the Chapters

3.2. Fraction of PHP-34 Drawn from Other Publications

3.3. Parts of PHP-34 Attributed to Wilson vs. Jungner

4. Origin of the Ten Principles

| By Chapman [7], Mountin [8] and Smillie [9], Published Between 1949 and 1952, as Cited in PHP-34 | Screening for Asymptomatic Disease by Levin-1955 [10] (Referring to Conferences held in 1951). | Principles and Procedures in the Evaluation of Screening for Disease by Thorner and Remein [6], Citing Blumberg. 1957 [14] | Some Principles of Early Diagnosis and Detection by Wilson In: Surveillance and Early Diagnosis in General Practice. Proceedings of Colloquium Held at Magdalen College, Oxford (Wednesday, 7 July 1965) [11] | The Case for General Screening Examinations in Middle Age by Wilson [12] | Monograph PHP-34, by Wilson and Jungner (1968) [1] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (1) Important problem. | (1) Should be an important public health problem (May be common, e.g., diabetes, or rare, e.g., phenylketonuria) | (1) The condition sought should be an important health problem. | |||

| (9) Amenability to treatment of the disease conditions detected | (1) What is the outlook for a person with the disease? The value of a true positive increases as the patient’s chances for cure or shorter convalescence are improved by early detection. In fact, when no health benefits are attributable to the finding of cases, the advisability of screening is doubtful | (2) Accepted treatment. | (2) There should be an accepted treatment for patients with recognized disease. | ||

| (2) Provision for diagnosis, follow-up and treatment is vitally important; without it case-finding must inevitably fall into disrepute | (10) Availability of adequate follow-up, including diagnostic and therapeutic care to all social and economic classes of persons in which disease is detected (lack of facilities for ultimate care should not be considered a bar to a screening program, provided there is a possible willingness on the part of the community to deal with needs revealed by the screening procedures). | (2) What facilities exist for treating cases found? The value of a true positive is reduced if inadequate facilities exist for treating those found. | (3) Facilities for diagnosis and treatment. | (4) Should be treatable when diagnosed | (3) Facilities for diagnosis and treatment should be available. |

| (4) Recognizable latent or early symptom stage. | (2) Should have a recognizable presymptomatic or early symptomatic stage | (4) There should be a recognizable latent or early symptomatic stage. | |||

| (6) Extent to which the procedure may be useful in screening for several diseases. | (6) Are healthy individuals being sought? Sometimes screening procedures are conducted to identify healthy rather than sick individuals. This may be the case in selecting people for certain jobs or for the armed services, as well as in screening life insurance applicants. In these cases, false negatives are very costly while false positives may not be. | (5) Suitable test or examination. | (3) A suitable test should be available | (5) There should be a suitable test or examination. | |

| (7) Compatibility of the tests included in the procedure with the purpose of the screening procedure, i.e., the discovery of disease | Tests used in screening must be relatively simple (…). Screening tests should be fairly sensitive, specific, precise and accurate | ||||

| (2) Acceptability to the individual being screened (8) Feasibility of properly interpreting to the public the need for screening, the results of screening, and the limitations of screening | (4) Who is going to do the diagnostic follow up? False positives burden the diagnostic facilities. If the facilities are adequate and diagnostic study is quite inexpensive, then false positives may be less harmful. False positives also serve to discredit screening | (6) Test acceptable to population. | (5) Screening should be acceptable to the public | (6) The test should be acceptable to the population. | |

| (7) Natural history adequately understood. | (7) The natural history of the condition, including development from latent to declared disease, should be adequately understood. | ||||

| (3) Acceptability to the professional groups concerned | (8) Agreed policy on treatment. | (8) There should be an agreed policy on whom to treat as patients. | |||

| (4) There is a danger that multiple screening might lead to the neglect of other aspects of community medical care because of the competing cost and possibly also because a false sense of security might be propagated. (5) The effect of multiple screening needs to be evaluated in terms of reduced morbidity and mortality. | (5) Cost, including accessibility of the population to be screened, time required for the test, physical facilities required, and personnel required. | (9) Cost related to other medical care expenditure. | (9) The cost of case-finding (including diagnosis and treatment of patients diagnosed) should be economically balanced in relation to possible expenditure on medical care as a whole. | ||

| (10) Continuing process | (10) Case-finding should be a continuing process and not a “once and for all” project. | ||||

| Principles not directly related to final principles in PHP-34 | |||||

| (3) Tests must be validated before they are applied to case-finding; harm may result to public health agencies’ relationships with the public (not to mention the direct harm to the public), and with the medical profession, from large numbers of fruitless referrals for diagnosis. (1) Case-finding by multiple screening is a technique well suited to public health departments, whose role is changing. | (1) Scientific validity of the procedure (4) Productivity of the procedure, i.e., the amount, and social and economic significance, of previously unknown disease likely to be detected | (3) What mental status accompanies knowledge or suspicion of the disease? If suspicion of a disease is accompanied by considerable anxiety that may in turn be debilitating, then demonstration of a true negative could provide valuable reassurance and health benefits (5) What is the likelihood of repeat screening within the community? If it is more likely that repeat screening will be carried on within a short period of time, then false negatives could be extremely detrimental. On the other hand, if screening will be repeated in a short period and the disease is not communicable or rapidly progressing, then false negatives would not be so harmful, since there may be a fair likelihood of uncovering the disease the next time | |||

5. Discussion

5.1. On the Origin of the Ten Wilson and Jungner Principles

5.2. Attribution of PHP-34 to Wilson vs. Jungner

6. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Wilson, J.M.G.; Jungner, G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1968. [Google Scholar]

- Jungner, L.; Jungner, I.; Engvall, M.; Döbeln, U.V. Gunnar Jungner and the Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2017, 3, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hall, K. Max Wilson and the Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2020, 6, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- World Health Organization; Regional Committee for Europe. The Presymptomatic Diagnosis of Diseases by Organized Screening Procedures (Fourteenth Session, Prague); EUR/RC14/Tech. Disc./6 (Mimeographed); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1964. [Google Scholar]

- Commission on Chronic Illness. Chronic Illness in the United States: Volume I–IV; Harvard University: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1957. [Google Scholar]

- Thorner, R.M.; Remein, Q.R. Principles and Procedures in the Evaluation of Screening for Disease; Public Health Monogr., No. 67 (Public Health Service Publication, No. 846); Public Health Service: Washington, DC, USA, 1961. [Google Scholar]

- Chapman, A.L. The concept of multiphasic screening. Public Health Rep. 1949, 64, 1311–1314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Mountin, J.W. Multiple screening and specialized programs. Public Health Rep. 1950, 65, 1359–1368. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smillie, W.G. Multiple screening. Am. J. Public Health Nation’s Health 1952, 42, 255–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Levin, M.L. Screening for asymptomatic disease; principles and background. J. Chronic Dis. 1955, 2, 367–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M.G. Some principles of early diagnosis and detection. In Surveillance and Early Diagnosis in General Practice, Proceedings of the Colloquium Held at Magdalen College, Oxford, UK; Teeling-Smith, G., Ed.; Office of Health Economics: London, UK, 1966; pp. 5–10. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.M. The case for general screening examinations in middle age. J. Coll. Gen. Pract. 1966, 11 (Suppl. 1), 83–88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, J.M.G.; Jungner, G. Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease; Draft May 4, 1967; WHO Library: Geneva, Switzerland, 1967; Available online: http://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/208882/WHO_PA_66.7_eng.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Blumberg, M.S. Evaluating health screening procedures. Oper. Res. 1957, 5, 351–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andermann, A.; Blancquaert, I.; Beauchamp, S.; Déry, V. Revisiting Wilson and Jungner in the genomic age: A review of screening criteria over the past 40 years. Bull. World Health Organ. 2008, 86, 317–319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Schnabel-Besson, E.; Mütze, U.; Dikow, N.; Hörster, F.; Morath, M.A.; Alex, K.; Brennenstuhl, H.; Settegast, S.; Okun, J.G.; Schaaf, C.P.; et al. Wilson and Jungner Revisited: Are Screening Criteria Fit for the 21st Century? Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2024, 10, 62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, J.M.G. Multiple screening. Lancet 1963, 2, 51–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO. Principles of Screening-Introducing a New Book; WHO Chronicle Nr. 22.; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1968; pp. 473–483. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, J.M. Problems in the evaluation of screening for disease. Ann. Soc. Belges Med. Trop. Parasitol. Mycol. 1970, 50, 489–503. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M. Current Status and Value of Laboratory Screening Tests [Abridged]: Principles of Screening for Disease. Proc. R. Soc. Med. 1971, 64, 1255–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M.G.J. Current trends and problems in health screening. Clin. Path. 1973, 26, 555–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ingram, R.M.; Holland, W.W.; Walker, C.; Wilson, J.M.; Arnold, P.E.; Dally, S. Screening for visual defects in preschool children. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1986, 70, 16–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, J.M.G. Medical screening: From beginnings to benefits: A retrospective. J. Med. Screen. 1994, 1, 121–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, J.M.G. Report on Multiphasic Screening (Report on WHO Travelling Fellowship to the U.S.A); 62 R/UK-13 (Mimeographed); World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Proceedings from the International Meetings on Automated Data Processing in Hospitals in Elsinore, Denmark, April–May 1966. Available online: http://infohistory.rutgers.edu/imia-documents/Elsinore1966-TOC-Program.pdf (accessed on 12 June 2025).

- Peterson, H.E.; Jungner, I. The History of the AutoChemist®: From Vision to Reality. Yearb. Med. Inform. 2014, 9, 235–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Wilson, J.M. The evaluation of the worth of early disease detection. J. R. Coll. Gen. Pract. 1968, 16 (Suppl. 2), 48–57. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

| Year (Month) | Event | Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 1949 | Publication paper Chapman [7] | Published on the concept of multiple screening with some references to ‘Principles’. |

| 1950 | Publication paper Mountin [8] | Published on the subject of multiple screening with special reference to test (acceptability to the public, specificity and sensitivity and cost-effectiveness) |

| 1951 | Meetings of the Commission on chronic illness | A series of meetings, the results of which ended up in a seminal report; the 1957 publication of Chronic Illness. |

| 1952 | Publication paper Smillie [9] | Published on multiple screening with a quite critical view to the advantages of multiple screening. |

| 1955 | Publication paper Levin [10] | Published a paper containing for the first time ten principles of screening. |

| 1957 | Symposium ‘Public Health Aspects of Chronic Disease’ Amsterdam, the Netherlands sponsored by W.H.O. Europe | Presentation of a paper of Dr. Lester Breslow, ‘Early detection of asymptomatic disease’ before a European audience, including Dr George Godber, senior colleague to Wilson. |

| 1957 | Publication ‘Chronic Illness in the United States’, by the Commission on Chronic Illness [5] | Publication of a four-volume work (of which many parts are adopted into the PHP-34) under the editorial supervision of Breslow. Wilson visited Breslow in the U.S.A. |

| 1961 | Publication of principles and procedures in the evaluation of screening for disease [6] | A seminal work by Thorner and Remein. Larger parts of this work find their way to PHP-34 and Wilson spoke with Thorner during his travels to the U.S.A. |

| 1962 | Travel Wilson to U.S.A. | Wilson visits 97 colleagues in the U.S.A. on a W.H.O. grant, encouraged by Godber. Many of those later receive prominent attention in the Monograph, their work is cited abundantly, and larger parts of the work are adopted in the PHP-34. |

| 1963 | Publication paper Lancet Wilson [17] | Report of Wilson of his W.H.O.-funded visit to the U.S.A. In this paper, no clear references to any principles could be discerned yet. Rather, Wilson highlighted the difference between the U.S.A. and U.K. public health landscape and how this will affect the adoption of screening for disease. |

| 1964 | W.H.O. meeting Prague | Jungner presenting together with Maria Missir on Public health screening. The name of Maria Missir will not reappear in W.H.O. discussions on screening. In the minutes of this conference, it was stated that all the participants had a keen interest in studying and developing organized screening services. |

| 1965 (July) | Magdelen College Colloquium, Oxford, U.K. | A conference in the U.K. with mostly U.K. representatives, amongst which was Wilson, but also Jungner and Dr. Collen, an American representative presenting on multiphasic screening. |

| 1965 (November) | W.H.O. meeting in Oslo, Norway, with Dr. A. Grundy and Wilson. | It took this second W.H.O. meeting after the one in Prague to start writing the monograph. Wilson gave a report to the W.H.O. Conference ‘Early Detection of Cancer’, Oslo, Norway, 15–19 November 1965. |

| 1966 | Publication of J Path Practice paper Wilson [12] | Introduction of 5 of the 10 principles that were published in 1968 in the monograph. Note: this paper could have been conceived before July 1965, so predating the Magdalen College Colloquium. |

| 1966 (April–May) | Elsinore conference | Conference in Denmark where Jungner presented on public health screening and laboratory test-automation |

| 1967 (May) | First draft-Principles and Practice screening for disease [13] | The fact that a full draft was available in May 1967 limits the production time of the Monograph to roughly between December 1965 and April–May 1967 |

| 1968 | Publication Monograph [1] | |

| 1968 | Publication in Chronicles W.H.O. [18] | The report of a 10-page interview with Max Wilson, sharing significant parts of the Monograph. While Jungner is mentioned in the introduction, the interview is with Wilson and is suggestive in many instances that Wilson is the writer of the monograph. |

| 1970 and 1971 | Publication papers Wilson [19,20] | On ‘Problems in the evaluation of screening for disease’ and on ‘Principles of screening for disease’ |

| 1973 | Publication papers Wilson [21] | On ‘Current trends and problems in health screening’. |

| 1982 | Jungner dies | - |

| 1986 and 1994 | Publication papers Wilson [22,23] | On Screening for visual defects in preschool children with the outcome that more research is needed to justify screening and a retrospective on medical screening, from beginnings to benefits. |

| 2009 | Wilson dies |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Neonatal Screening. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Schielen, P.C.J.I. Historical Appreciation of World Health Organization’s Public Health Paper-34: Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, by Max Wilson and Gunnar Jungner. Int. J. Neonatal Screen. 2025, 11, 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030056

Schielen PCJI. Historical Appreciation of World Health Organization’s Public Health Paper-34: Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, by Max Wilson and Gunnar Jungner. International Journal of Neonatal Screening. 2025; 11(3):56. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030056

Chicago/Turabian StyleSchielen, Peter C. J. I. 2025. "Historical Appreciation of World Health Organization’s Public Health Paper-34: Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, by Max Wilson and Gunnar Jungner" International Journal of Neonatal Screening 11, no. 3: 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030056

APA StyleSchielen, P. C. J. I. (2025). Historical Appreciation of World Health Organization’s Public Health Paper-34: Principles and Practice of Screening for Disease, by Max Wilson and Gunnar Jungner. International Journal of Neonatal Screening, 11(3), 56. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijns11030056