How Does a Medical Team in the Oncology Department React to the COVID-19 Pandemic?

Abstract

:Introduction

- :

- Do these healthcare workers in the Oncology Department experience stress as a result of the situation generated by the pandemic?

- :

- What are the main sources of stress?

- :

- Which psycho-emotional symptoms and which physical reactions do they report?

- :

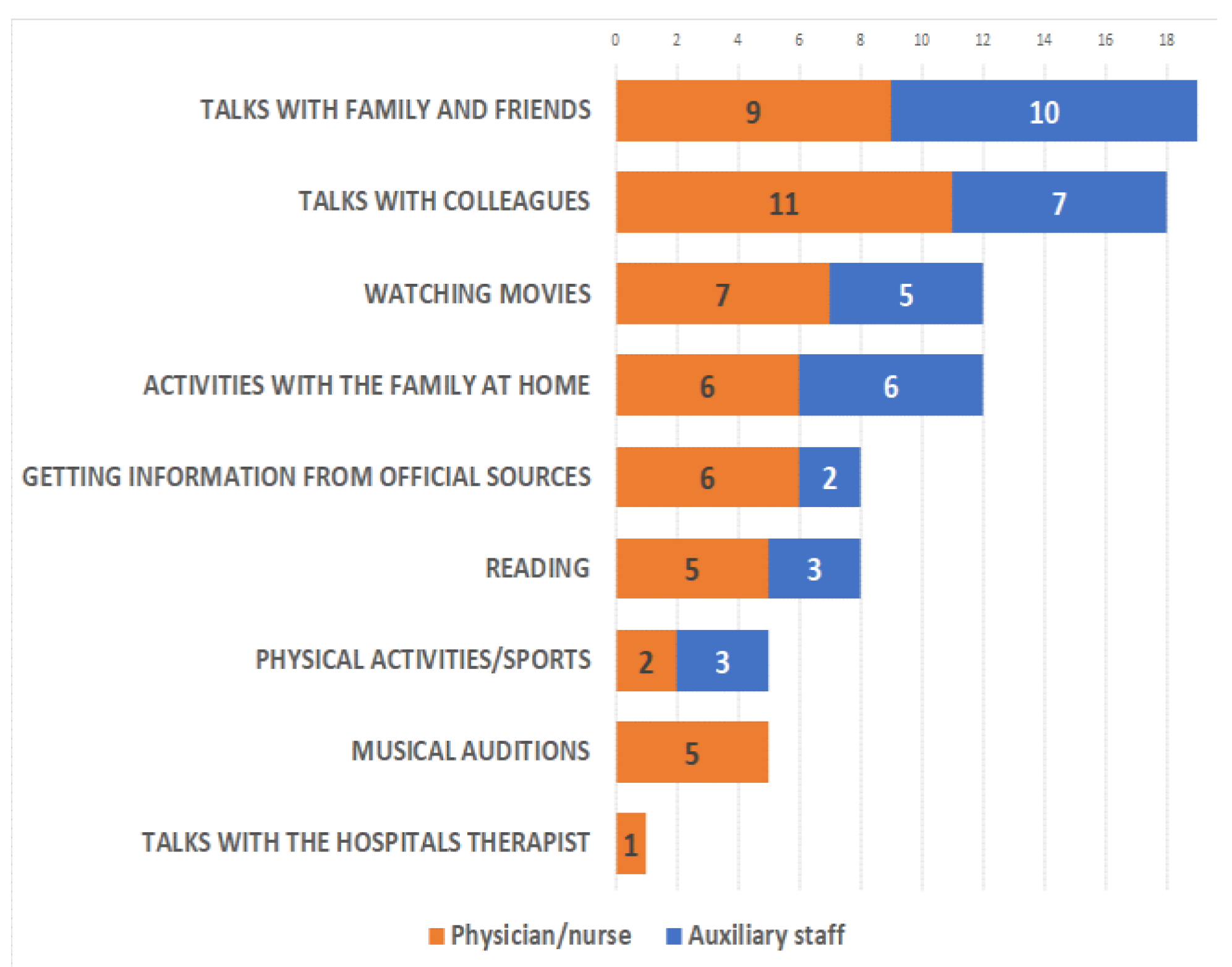

- Which coping mechanisms do they use given the situation?

Materials and Methods

- Type of work:

- −

- direct contact with patients; physician/nurse = healthcare professional

- −

- no direct contact with patients = supporting healthcare worker

- Stress:

- −

- completely – almost completely adapted = no distress

- −

- not at all – a little bit – kind of adapted = quite distressed

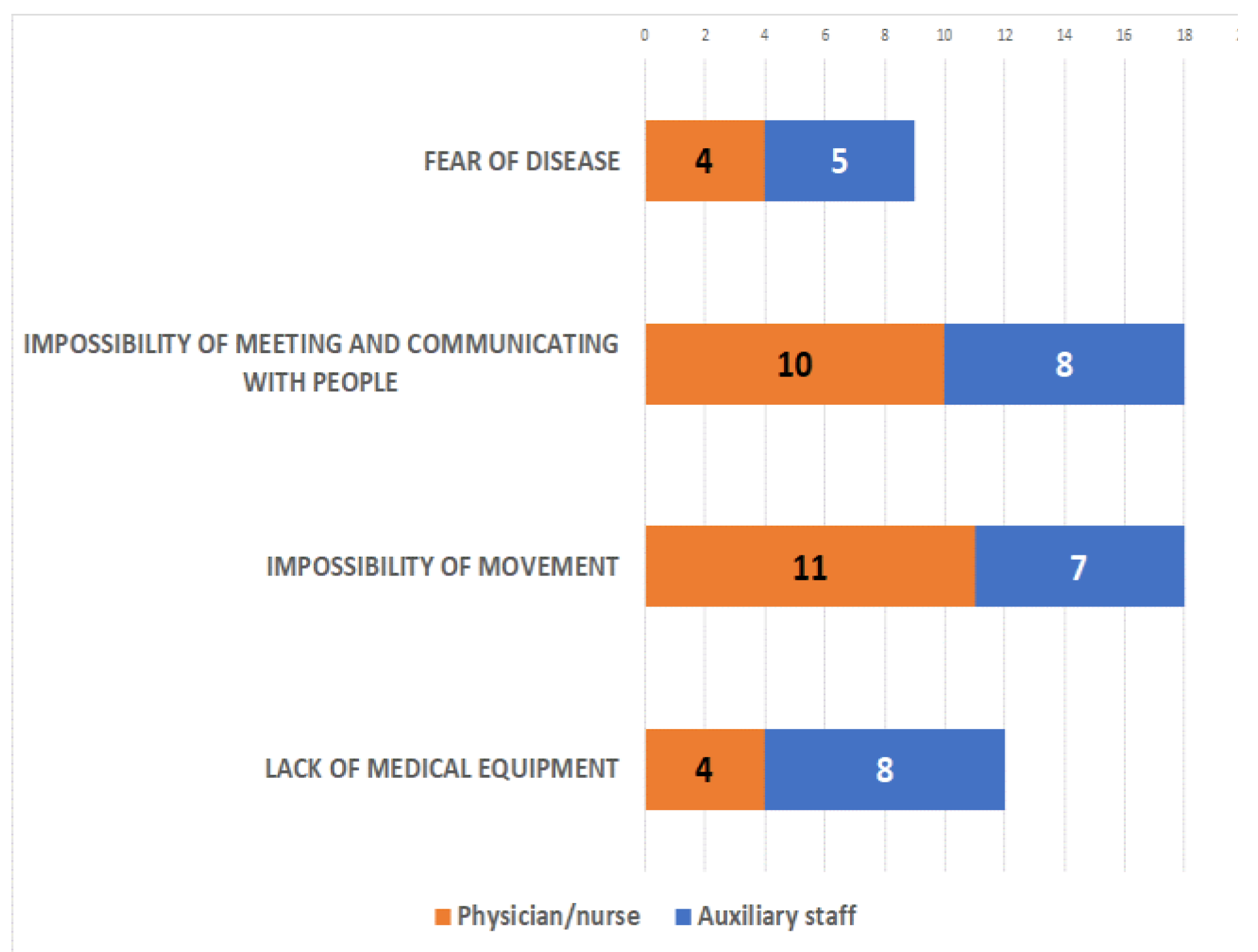

- Source of stress:

- −

- fear of disease – lack of medical equipment – fear of death – impossibility in meeting and communicating with other people – impossibility of moving around: the sum of each answer “yes”.

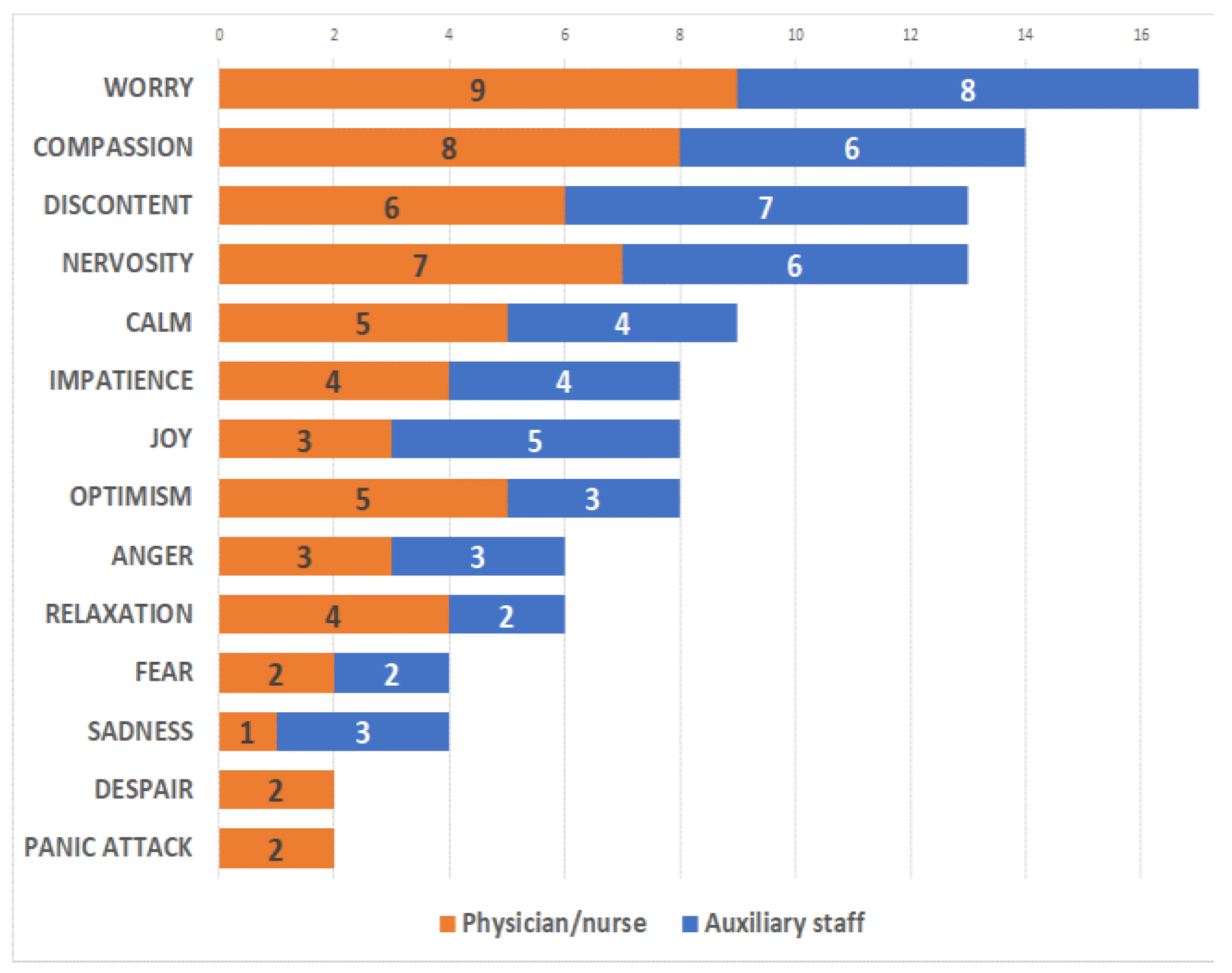

- Psychological/ emotional symptoms:

- −

- positive symptoms (joy – optimism – relaxation – calmness – compassion): number of “yes” answers;

- −

- negative symptoms (sadness – despair – discontent – fear – impatience – worry– nervousness – anger – panic); number of “yes” answers.

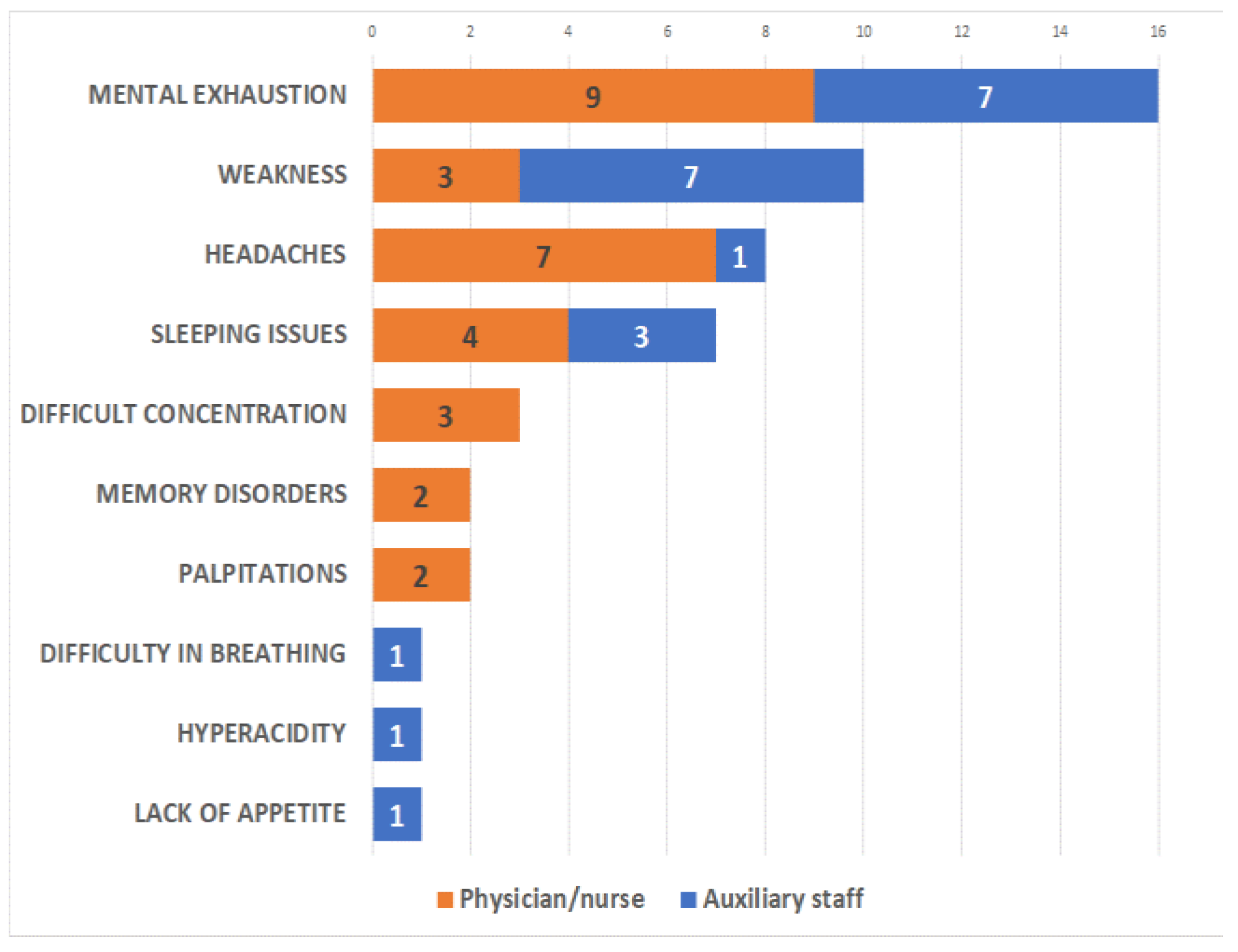

- Physical reactions:

- −

- loss of appetite – weakness – mental exhaustion – palpitations – difficulties in breathing – hyper-action – sleeping issues – memory disorders – difficult concentration - headache: number of “yes” answers.

Results

Discussions

Highlights

- ✓

- Healthcare institutions should ensure sufficient support, including providing tailored education and training, and ensuring adequate resources.

- ✓

- The psychosocial need should be monitored to reduce the levels of anxiety and stress. Family and colleagues may play an important role.

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest disclosure

Compliance with ethical standards

Acknowledgments

References

- Jansson, M.; Rello, J. Mental Health in Healthcare Workers and the Covid-19 Pandemic Era: Novel Challenge for Critical Care. J Intensive & Crit Care. 2020, 6, 6. [Google Scholar]

- Serban, D.; Smarandache, C.G.; Tudor, C.; Duta, L.N.; Dascalu, A.M.; Aliuș, C. Laparoscopic Surgery in COVID-19 Era- Safety and Ethical Issues. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020, 10, 673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joob, B.; Wiwanitkit, V. Traumatization in medical staff helping with COVID-19 control. Brain Behav Immun. 2020, 87, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, Z.; Zheng, S.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, X.; Qiu, Z.; Huang, A.; Wu, K. Emotional and Cognitive Responses and Behavioral Coping of Chinese Medical Workers and General Population during the Pandemic of COVID-19. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2020, 17, 6198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dascalu, A.M.; Tudosie, M.S.; Smarandache, G.C.; Serban, D. Impact of the covid-19 pandemic upon the ophthalmological clinical practice. Rom J Legal Med. 2020, 28, 96–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shah, H.; Shah, R.; Sanghani, H.; Lakhani, N. Health related quality of life (HRQoL) and its associated surgical factors in diabetes foot ulcer patients. J Clin Invest Surg 2020, 5, 83–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temsah, M.H.; Al-Sohime, F.; Alamro, N.; Al-Eyadhy, A.; Al-Hasan, K.; Jamal, A.; Al-Maglouth, I.; Aljamaan, F.; Al Amri, M.; Barry, M.; Al-Subaie, S.; Somily, A.M. The psychological impact of COVID-19 pandemic on health care workers in a MERS-CoV endemic country. J Infect Public Health 2020, 13, 877–882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, M.; Guo, L.; Yu, M.; Jiang, W.; Wang, H. The psychological and mental impact of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) on medical staff and general public - A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychiatry Res 2020, 291, 113190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suceveanu, A.I.; Mazilu, L.; Suceveanu, A.P.; Parepa, I.; Dumitrescu, I.B.; Drăgoi, C.M.; Nicolae, A.C.; Botea, F.; Voinea, F.; Burcea-Dragomiroiu, G.T. Assertion for montelukast in the covid-19 pandemics? Farmacia. 2020, 68, 579–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D.; Socea, B.; Balasescu, S.A.; Badiu, C.D.; Tudor, C.; Dascalu, A.M.; Vancea, G.; Spataru, R.I.; Sabau, A.D.; Sabau, D.; Tanasescu, C. Safety of Laparoscopic Cholecystectomy for Acute Cholecystitis in the Elderly: A Multivariate Analysis of Risk Factors for Intra and Postoperative Complications. Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badiu, C.D.; Rahnea Nita, G.; Ciuhu, A.N.; Manea, C.; Smarandache, C.G.; Georgescu, D.G.; Bedereag, S.I.; Cocosila, C.L.; Braticevici, B.; Mehedintu, C.; Grigorean, V.T. Neuroendocrine renal carcinoma – therapeutic and diagnostic issues. Acta Endocrinol (Buchar) 2016, 12, 355–361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D.; Papanas, N.; Dascalu, A.M.; Stana, D.; Nicolae, V.A.; Vancea, G.; Badiu, C.D.; Tanasescu, D.; Tudor, C.; Balasescu, S.A.; Pantea-Stoian, A. Diabetic Retinopathy in Patients With Diabetic Foot Ulcer: A Systematic Review. Int J Low Extrem Wounds. 2021, 20, 98–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popa, C.C.; Badiu, D.C.; Andronache, L.F.; Costea, R.V.; Neagu, S.I.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Socea, B.; Ionescu, D. Differential Diagnosis in Esophageal Cancer. Review on literature. Rev Chim. 2019, 70, 331–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gheorghe, G.; Ilie, M.; Bungau, S.; Stoian, A.M.P.; Bacalbasa, N.; Diaconu, C.C. Is There a Relationship between COVID-19 and Hyponatremia? Medicina (Kaunas) 2021, 57, 55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pantea Stoian, A.; Pricop-Jeckstadt, M.; Pana, A.; Ileanu, B.V.; Schitea, R.; Geanta, M.; Catrinoiu, D.; Suceveanu, A.I.; Serafinceanu, C.; Pituru, S.; Poiana, C.; Timar, B.; Nitipir, C.; Parvu, S.; Arsene, A.; Mazilu, L.; Toma, A.; Hainarosie, R.; Ceriello, A.; Rizzo, M.; Jinga, V. Death by SARS-CoV 2: a Romanian COVID-19 multi-centre comorbidity study. Sci Rep 2020, 10, 21613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rotaru, M.; Iancu, G.M.; Gheucă Solovăstru, L.; Glaja, R.F.; Grosu, F.; Bold, A.; Costache, A. A rare case of multiple clear cell acanthoma with a relatively rapid development of the lower legs. Rom J Morphol Embryol 2014, 55, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Anca, P.S.; Toth, P.P.; Kempler, P.; Rizzo, M. Gender differences in the battle against COVID-19: Impact of genetics, comorbidities, inflammation and lifestyle on differences in outcomes. Int J Clin Pract 2021, 75, e13666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoian, A.P.; Catrinoiu, D.; Rizzo, M.; Ceriello, A. Hydroxychloroquine, COVID-19 and diabetes. Why it is a different story. Diabetes Metab Res Rev 2021, 37, e3379. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, B.; Oașă, I.D.; Bertesteanu, S.V.; Balalau, C.; Scaunasu, R.; Manole, F.; Domuta, M.; Oancea, A.L. Emergency tracheostomy protocols in Coltea Clinical Hospital in patients with SARS-CoV-2 infection. J Clin Invest Surg. 2020, 5, 34–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sakka, S.; Nikopoulou, V.A.; Bonti, E.; Tatsiopoulou, P.; Karamouzi, P.; Giazkoulidou, A.; Tsipropoulou, V.; Parlapani, E.; Holeva, V.; Diakogiannis, I. Assessing test anxiety and resilience among Greek adolescents during COVID-19 pandemic. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 173–178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Catrinoiu, D.; Ceriello, A.; Rizzo, M.; Serafinceanu, C.; Montano, N.; Pantea Stoian, A.; Udeanu, D.I.; et al. Diabetes And Renin-Angiotensin-Aldosterone System: Implications For Covid-19 Patients With Diabetes Treatment Management. Farmacia. 2020, 68, 377–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dimitriu, M.C.T.; Pantea-Stoian, A.; Smaranda, A.C.; Nica, A.A.; Carap, A.C.; Constantin, V.D.; Davitoiu, A.M.; Cirstoveanu, C.; Bacalbasa, N.; Bratu, O.G.; Jacota-Alexe, F.; Badiu, C.D.; Smarandache, C.G.; Socea, B. Burnout syndrome in Romanian medical residents in time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Med Hypotheses 2020, 144, 109972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D.; Branescu, C.M.; Smarandache, C.G.; Tudor, C.; Tanasescu, C.; Tudosie, M.S.; Stana, D.; Comandasu, M.; Costea, D.O.; Dascalu, A.M. Safe surgery in Day Care Centers - Focus on preventing medico-legal issues. Rom J Leg Med. 2021, 29, 60–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costea, D.O.; Enache, F.D.; Baz, R.; Suceveanu, A.P.; Suceveanu, A.I.; Ardeleanu, A.; Mazilu, L.; Costea, A.C.; Botea, F.; Voinea, F. Confirmed child patient with COVID-19 infection, operated for associated surgical pathology – first pediatric case in Romania. Rom Biotechnol Lett. 2020, 25, 2107–2110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serban, D.; Socea, B.; Badiu, C.D.; Tudor, C.; Balasescu, S.A.; Dumitrescu, D.; Trotea, A.M.; Spataru, R.I.; Vancea, G.; Dascalu, A.M.; Tanasescu, C. Acute surgical abdomen during the COVID-19 pandemic: Clinical and therapeutic challenges. Exp Ther Med 2021, 21, 519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marina, C.N.; Gheoca-Mutu, D.E.; Răducu, L.; Avino, A.; Brîndușe, L.A.; Stefan, C.M.; Scaunasu, R.V.; Jecan, C.R. COVID-19 outbreak impact on plastic surgery residents from Romania. J Mind Med Sci 2020, 7, 212–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vacca, A.; Minò, M.V.; Colizzi, I.; Solomita, B.; Longo, R.; Franza, F.; Tavormina, G. The Emotional Impact of the Operator in the Care of Patients With Mental Disorders during the Pandemic: Measure of Interventions on Compassion Fatigue and Burn-Out. Psychiatr Danub. 2021, 33 (Suppl 9), 108–113. [Google Scholar]

- Veeraraghavan, V.; Srinivasan, K. Work place impact on mental wellbeing of frontline doctors. J Mind Med Sci. 2020, 7, 188–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuhu, A.N.; Badica, R.; Popescu, M.; Radoi, M.; Rahnea-Nita, R.A.; Rahnea-Nita, G. Defense mechanisms and coping style at very next diagnostic period in advanced and metastatic cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology 2016, 34, e21610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnea-Nita, R.A.; Paunica, S.; Motofei, C.; Rahnea-Nita, G. Assessment of anxiety and depression in patients with advanced gynaecological cancer. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology 2019, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciuhu, A.N.; Rahnea-Nita, G.; Popescu, M.; Rahnea-Nita, R.A. Evaluation of quality of life in patients with advanced and metastatic breast cancer proposed for palliative chemotherapy and best supportive care versus best supportive care [abstract]. In: Proceedings of the Thirty-Seventh Annual CTRC-AACR San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium: 2014 Dec 9-13; San Antonio, TX. Philadelphia (PA): AACR; Cancer Res 2015, 75, P5-15–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Popescu, B.; Doinița, O.I.; Bălălău, C.; Scăunașu, R.; Manole, F.; Domuța, M.; Oancea, A.L. Fibroscopic examination on ENT patients in COVID-19 era. J Clin Invest Surg. 2020, 5, 63–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahnea-Nita, G.; Rahnea-Nita, R.A.; Soare, I.; Stoica, E.; Gociu, M.; Ciuhu, A.N. Management of burnout syndrome at palliative care team. Paliatia. Journal of Palliative Care 2019, 12. [Google Scholar]

- Rahnea-Nita, R.A.; Rahnea-Nita, G.; Stoian, A.R.; Ciuhu, A.N. Management of cancer patients during Covid 19 pandemic. Paliatia, Journal of Palliative Care 2020, 13. [Google Scholar]

- Tomulescu, V.; Surlin, V.; Scripcariu, V.; Bintintan, V.; Duta, C.; Calu, V.; Popescu, I.; Saftoiu, A.; Copaescu, C. Colorectal Surgery in Romania during the COVID-19 Pandemic. Chirurgia (Bucur). 2020, 115, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Share and Cite

Omer, S.; Smarandache, A.M.; Omer, I.; Ciuhu, A.-N.; Rahnea-Nita, R.-A.; Grigorean, V.-T.; Andronache, L.F.; Stoian, A.-R. How Does a Medical Team in the Oncology Department React to the COVID-19 Pandemic? J. Mind Med. Sci. 2021, 8, 286-291. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.82.P286291

Omer S, Smarandache AM, Omer I, Ciuhu A-N, Rahnea-Nita R-A, Grigorean V-T, Andronache LF, Stoian A-R. How Does a Medical Team in the Oncology Department React to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2021; 8(2):286-291. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.82.P286291

Chicago/Turabian StyleOmer, Secil, Andreea Maria Smarandache, Ioana Omer, Anda-Natalia Ciuhu, Roxana-Andreea Rahnea-Nita, Valentin-Titus Grigorean, Liliana Florina Andronache, and Alexandru-Rares Stoian. 2021. "How Does a Medical Team in the Oncology Department React to the COVID-19 Pandemic?" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 8, no. 2: 286-291. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.82.P286291

APA StyleOmer, S., Smarandache, A. M., Omer, I., Ciuhu, A.-N., Rahnea-Nita, R.-A., Grigorean, V.-T., Andronache, L. F., & Stoian, A.-R. (2021). How Does a Medical Team in the Oncology Department React to the COVID-19 Pandemic? Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 8(2), 286-291. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.82.P286291