Introduction

The world is facing a challenging and life-changing period during the novel coronavirus pandemic. On the 11 March 2020, the World Health Organization declared the virus outbreak a pandemic, affecting different parts of the globe with variable infection rates and host responses [

1]. The first COVID-19 case in Romania was reported on 26 February 2020, and since then, the spread of the disease had been on the rise. On the 15 March, the government declared a state of emergency. The Institutes of Health had constantly provided information about the risk of infection and recommendation on protective measures with the necessity of social distancing [

2].

In order to combat the acute crisis of high rate of hospital admissions, lack of protective gear, and insufficient medical personnel, several strategies were implemented nationwide to minimize the use of medical resources. Consequently, surgery departments reduced the capacity by performing only acute, severe or oncological operations required by law [

3]. Healthcare professionals, including emergency physicians, primary care physicians, anesthesiologists and infectious disease specialists, were trained as first line medical staff to treat the SARS-CoV-2 infected patients [

4].

The dramatic changes in the work environment demanded plastic surgery teams to adapt constantly and rapidly in order to reduce the risk for patients, physicians, and other healthcare workers, and to achieve greater clinical effectiveness [

5]. Working in alternating shifts, in smaller groups, performing urgent and emergency procedures, and wearing specific equipment were the main measures taken initially by the clinicians, managers, and government.

Even though for trainees practicing plastic and reconstructive surgery maneuvers occurred less frequently due to the restrictions imposed by the ongoing COVID-19 situation, the theoretical approach of the specialty came into compensation. Therefore, online courses, webinars, virtual meetings, and workshops provided important knowledge and information not only for residents, but for all the practitioners [

6].

The main purpose of this study was to evaluate the changes in Plastic Surgery residents’ training that resulted from the COVID-19 outbreak.

Materials and Methods

An anonymous questionnaire using Google form, a free Internet platform, was distributed to the plastic surgery residents from all training centers in Romania. The questionnaire included a series of questions regarding the year of residency, the training program attended, the influence of COVID-19 outbreak on their surgical practice, their exposure to the virus, and whether they were fearful of contacting the virus.

In addition, participants were asked if COVID-19 tests had been performed and protective measures had been taken in order to keep at a minimum the rate of infection of personnel in the hospitals that did not specifically treat coronavirus.

Statistical analysis. The results are presented as numbers and relative frequencies for the collected qualitative variables. We tested the difference between the proportions using the chi square test and the Fisher exact test. To study the correlations, Pearson correlation test was used. The threshold of 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis of the data was performed using SPSS 23.0.

Results

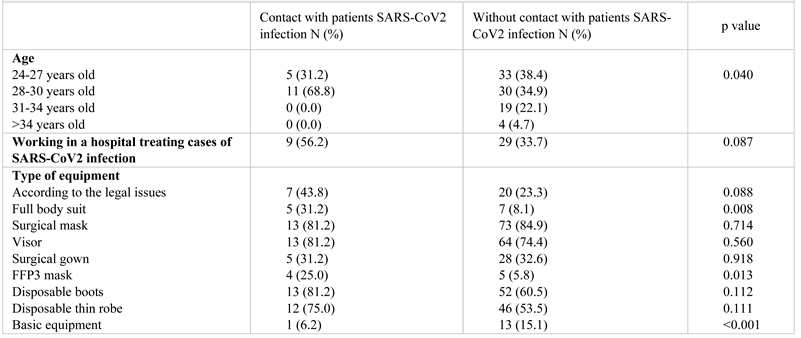

The questionnaire was answered by 102 plastic surgery residents from all the 9 training centers in Romania, residents from the 2nd, 3rd and 4th year of training, aged between 28 and 30 years old (40.2%). Considering their activity and their work environment, 37.3% were working in hospitals that admit and treat patients infected with SARS-CoV-2, having a higher chance of contracting the disease. The proportion of residents who had contact with SARS-CoV2 patients differed significantly (

p = 0.040) depending on the age group (

Table 1). In 86.3 % of the hospitals, the patients were tested at admission, in order to avoid the contact of a potentially infected person with healthy personnel or patients. This testing used RT-PCR tests in most of the cases (83.3%), associated with rapid immunological tests (35.3%). Even though CT-Scans offered valuable information about the disease, they had been performed on only a few cases when symptomatology was present and tests were negative.

Regarding protective measures, residents were using surgical masks and protective face shields, combined with different types of surgical gowns depending if the patient had a confirmed case of SARS CoV-2 infection. If surgery was necessary for a coronavirus patient, additional protective equipment was required, such as gowns, gloves, FFP3 masks, eye protection, aprons, and boots, following entirely the procedures implemented by the World Health Organization. Residents working with COVID patients more frequently used protective full body suits (

p = 0.008) and FPP3 masks (

p = 0.013) than those who did not work with infected patients (

p <0.001) (

Table 1).

15.7% of the residents had contact with a coronavirus patient and only 63.2% of them had adequate protective equipment. Most of these residents were exposed during the first period of the outbreak, when inter-community transmission was considered nearly impossible. Those residents were isolated and only one developed symptoms of COVID-19 and tested positive.

Regarding surgical training, 42.2% of the residents responded that their surgical activity diminished by 75%, while 44.1% reported a decrease of nearly 95%. Surgeries performed during this period were hand and facial trauma, as well as infected wounds that required surgical debridement. Non-essential elective surgeries or breast reconstruction had not been performed during the outbreak, being banned by the law and hospital management. Nearly half of the residents did shifts, the others going to the hospital every 2 or 3 days, respectively weekly (

Table 2).

Residents working in non-COVID hospitals attended online meetings, laboratory activities, and research with a notably increased frequency (

p < 0.001) (

Table 2). Concerning the theoretical knowledge, 53.9% of the departments tried to counterbalance the deficient practical approach of the specialty by organizing online learning modules, with presentations of surgical cases and didactic sessions. Likewise, 93% of the residents declared that they had more time to study the theoretical part of their specialty. Even if the surgical training was affected during this outbreak, 56,9% of the residents considered that the residency program should not be extended. The others had considered the extension a necessity if the outbreak last more than 4 to 6 months.

The psychological impact of COVID-19 outbreak was also assessed. The residents were mainly concerned with their family health status and their own risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 (36.3%). The psychological impact of the pandemic was greater for the residents working in COVID hospitals (

p = 0.001), they also considered to a greater extent that the pandemic had had a significant negative impact on their surgical training (

p <0.001) (

Table 2).

The year of residency significantly correlates negatively with the impairment of surgical training (

p = 0.007) and positively with the time allocated to study (

p = 0.032). Residents who had more time to study considered that it was not necessary to extend the residency period (

p = 0.008), and they also were less psychologically affected. They considered that the COVID 19 outbreak did not have an impact on their health status (

p = 0.001) and raise concern about their family health status (

p = 0.017) and their surgical training (

p = 0.009). Those residents who were psychologically affected preferred the extension of the residency program (

p = 0.005) and were also worried about their health status (

p = 0.004), their families’ health status (

p = 0.001), and the impact on their surgical training (

p = 0.001) (

Table 2). Trainees who were anxious about their health status (

p = 0.001) or the negative effects imposed by the outbreak on their surgical training (

p = 0.009) were less interested in improving their theoretical knowledge.

Discussion

The COVID-19 outbreak produced a paradigm shift in people’s life, changing their lifestyle, their concerns, and even their income. Plastic surgeons were recommended to postpone their elective surgeries because of the infection risk, the higher mortality rate in asymptomatic patients [

7], and the necessity of preservation of the vital resources. Also, the number of emergency surgeries represented by trauma cases diminished due to the lockdown.

The residents working in emergency hospitals who were exposed to COVID-19 patients showed concern about their health and their family risk of infection. Most tried to isolate, which impacted their quality of life and increased their anxiety and risk of depression.

Regarding their education and training during the outbreak, plastic surgery residents taking coursework on surgery had to identify other methods of learning. Within the plastic surgery department, physical-contact meetings and gatherings for didactic purposes were no longer held, social distancing being practiced. Furthermore, all conferences and congresses were postponed or cancelled, personal development of the trainees in their specialty being highly limited. Thus, the residency coordinators supplemented with online learning sessions in order to cover the plastic surgery education curriculum [

8].

Moreover, webinars organized by international experts from the main plastic surgery societies became an important resource for the residents. These international webinars permitted them to have access to international experts’ knowledge and clinical case discussions, free of charge, in comparison with conferences or congresses.

The time allocated to the process of learning was valuable and allowed the young doctors to improve their training skills, acquire crucial information, connect with colleagues from other countries, and exchange opinions and ideas on different techniques or subjects [

9]. Furthermore, the time spent outside the operating room had been used in studying more about surgery and anatomy [

10]. This study was based on the responses of half of all the plastic surgery residents from Romania, and brought relevant information regarding their concerns and the impact of pandemic on their surgical training. The major limitations of the study were the 50% response rate of the population, and the short timeframe analyzed from the onset of COVID-19 pandemic, which did not permit an accurate assessment on the longer-term impact of the pandemic.