Personality Dimensions and Attributional Styles in Individuals With and Without Gender Dysphoria

Highlights

- Patients with gender dysphoria have significantly higher neuroticism and lower agreeableness.

- Patients with gender dysphoria have significantly lower positive attributional style.

Highlights

- Patients with gender dysphoria have significantly higher neuroticism and lower agreeableness.

- Patients with gender dysphoria have significantly lower positive attributional style.

Abstract

Introduction

Personality, attributional styles and gender dysphoria

Theoretical approaches of Gender Dysphoria

Materials and Methods

The present study

Participants

Assessment Instruments

Procedure

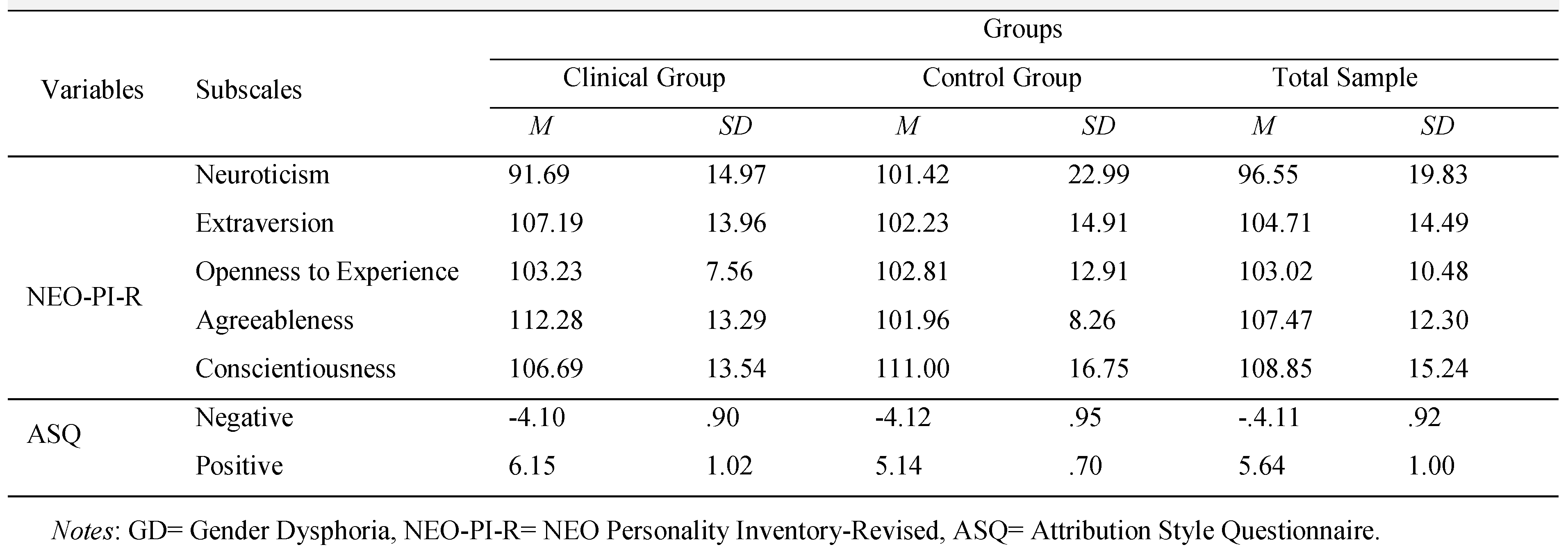

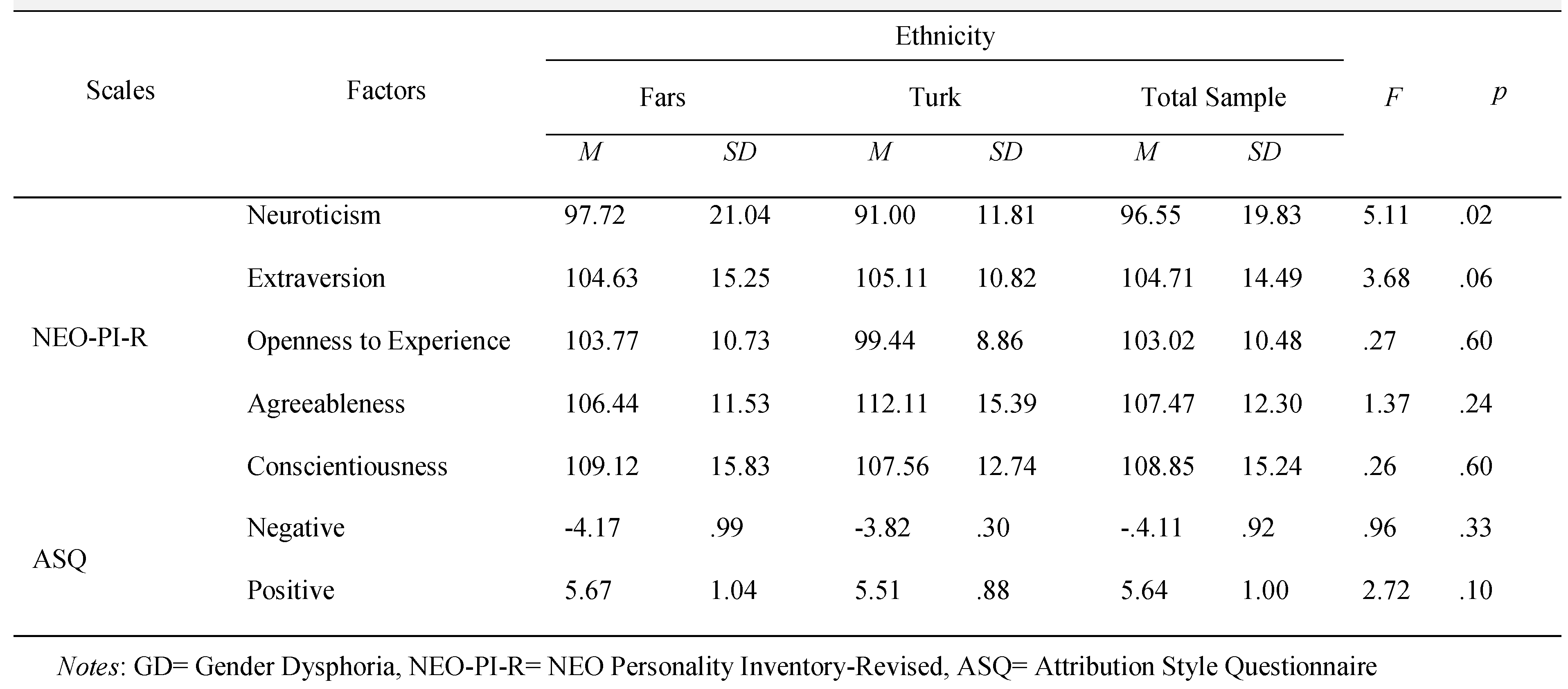

Results

Discussions

Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest disclosure

Compliance with Ethical Standards

References

- Pichot, P. DSM-III: The 3d edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders from the American Psychiatric Association. Rev Neurol (Paris). 1986, 142, 489–499. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; Gooren, L.j. Transsexualism: A review of etiology, diagnosis and treatment. J Psychosom Res. 1999, 46, 315–333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ehrbar, R.D. Consensus from differences: Lack of professional consensus on the retention of the gender identity disorder diagnosis. International Journal of Transgenderism. 2010, 12, 60–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hird, M.J. Unidentified pleasures: Gender identity and its failure. Body & Society. 2002, 8, 39–54. [Google Scholar]

- Schrock, D.; Reid, L.; Boyd, E.M. Transsexuals’ embodiment of womanhood. Gender & Society. 2005, 19, 317–335. [Google Scholar]

- Vstarcevic, V.S.; Rossi Monti, M.; D'Agostino, A.; Berle, D. Will DSM-5 make us feel dysphoric? Conceptualisation(s) of dysphoria in the most recent classification of mental disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2013, 47, 954–960. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American_Psychiatric_Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 5th ed.; American_Psychiatric_Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2013; ISBN-13: 978-0890425558. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Falgueras, A. Gender dysphoria and body integrity identity disorder: Similarities and differences. Psychology. 2014, 5, 160–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Fuqua, J.; Eugster, E.A. Characteristics of referrals for gender dysphoria over a 13-year period. J Adolesc Health. 2016, 58, 369–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, K.J.; Lawrence, A.A.; Kreukels, B.P. Gender dysphoria in adults. Annu Rev Clin Psychol. 2016, 12, 217–247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cole, C.M.; O'boyle, M.; Emory, L.E.; Meyer, W.J., III. Comorbidity of gender dysphoria and other major psychiatric diagnoses. Arch Sex Behav. 1997, 26, 13–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- American_Psychiatric_Association. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders, 4th ed.; tex t rev; American_Psychiatric_Association: Washington, DC, USA, 2000; ISBN-13: 978-0890420256. [Google Scholar]

- Bodlund, O.; Armelius, K. Self-image and personality traits in gender identity disorders: An empirical study. J Sex Marital Ther. 1994, 20, 303–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bodlund, O.; Kullgren, G.; Sundbom, E.; Höjerback, T. Personality traits and disorders among transsexuals. Acta Psychiatr Scand. 1993, 88, 322–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jonas, C.H. An objective approach to the personality and environment in homosexuality. The Psychiatric Quarterly. 1944, 18, 626–641. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fleming, M.; Cohen, D.; Salt, P.; Jones, D.; Jenkins, S. A study of pre-and postsurgical transsexuals: MMPI characteristics. Arch Sex Behav. 1981, 10, 161–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosen, A.C. Brief report of MMPI characteristics of sexual deviation. Psychol Rep. 1974, 35, 73–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grant, J.E.; Flynn, M.; Odlaug, B.L.; Schreiber, L. Personality disorders in gay, lesbian, bisexual, and transgender chemically dependent patients. Am J Addict. 2011, 20, 405–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Duišin, D.; Batinić, B.; Barišić, J.; Djordjevic, M.L.; Vujović, S.; Bizic, M. Personality disorders in persons with gender identity disorder. ScientificWorldJournal. 2014, 2014, 809058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Settineri, S.; Merlo, E.M.; Bruno, A.; Mento, C. Personality Assessment in Gender Dysphoria: Clinical observation in psychopathological evidence. Mediterranean Journal of Clinical Psychology. 2016, 4, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barisic, J.; Duisin, D.; Djordjevic, M.; Vujovic, S.; Bizic, M. Influence of basic personality dimensions on adaptation processes and quality of life in patients with gender dysphoria in post transitory period. In Proceedings of the 2nd Contemporary Trans Health in Europe: Focus on Challenges and Improvements, Belgrade, Serbia, 6–8 April 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez, X.; Stewart, S.; Jacobson-Dickman, E. Approach to Children and Adolescents with Gender Dysphoria. Pediatr Rev. 2016, 37, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ettner, R. Care of the elderly transgender patient. Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes. 2013, 20, 580–584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kreukels, B.P.C.; Köhler, B.; Nordenström, A.; Roehle, R.; Thyen, U.; Bouvattier, C.; de Vries, A.L.C.; Cohen-Kettenis, P.T.; dsd-LIFE group. Gender Dysphoria and Gender Change in Disorders of Sex Development/Intersex Conditions: Results From the dsd-LIFE Study. J Sex Med. 2018, 15, 777–785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacLusky, N.J.; Naftolin, F. Sexual differentiation of the central nervous system. Science. 1981, 211, 1294–1302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hines, M.; Constantinescu, M.; Spencer, D. Early androgen exposure and human gender development. Biol Sex Differ. 2015, 6, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zucker, K.J.; Wood, H.; Singh, D.; Bradley, S.J. A developmental, biopsychosocial model for the treatment of children with gender identity disorder. J Homosex. 2012, 59, 369–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Haldeman, D.C. Gender atypical youth: Clinical and social issues. School Psychology Review. 2000, 29, 192–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kessler, S.J.; McKenna, W. Gender construction in everyday life: Transsexualism (abridged). Feminism & Psychology. 2000, 10, 11–29. [Google Scholar]

- Rosqvist, H.B.; Nordlund, L.; Kaiser, N. Developing an authentic sex: Deconstructing developmental– psychological discourses of transgenderism in a clinical setting. Feminism & Psychology. 2014, 24, 20–36. [Google Scholar]

- Yost, M.R.; Smith, T.E. Transfeminist psychology. Feminism & Psychology. 2014, 24, 145–156. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, D.P.; Long, A.E.; McPhearson, A.; O'brien, K.; Remmert, B.; Shah, S.H. Personality and gender differences in global perspective. Int J Psychol. 2017, 52 (Suppl. S1), 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lev, A.I. Gender dysphoria: Two steps forward, one step back. Clinical social work journal. 2013, 41, 288–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winters, K. Gender madness in American psychiatry: Essays from the struggle for dignity; GID Reform Advocates: Dillon, CO, 2008; ISBN-13: 978-1439223888. [Google Scholar]

- Berlin, F.S. A conceptual overview and commentary on gender dysphoria. J Am Acad Psychiatry Law. 2016, 44, 246–252. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Martin, C.L.; Ruble, D.N.; Szkrybalo, J. Cognitive theories of early gender development. Psychol Bull. 2002, 128, 903–933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stoller, R.J. The mother's contribution to infantile transvestic behaviour. Int J Psychoanal. 1966, 47, 384–395. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zucker, K.J.; Bradley, S.J. Gender identity disorder and psychosexual problems in children and adolescents. Can J Psychiatry. 1990, 35, 477–486. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Rottnek Matthew. In Sissies and tomboys: Gender nonconformity and homosexual childhood; 1999; ISBN 9780814774847.

- Lev, A.I. Transgender emergence; Haworth Clinical Practice Press: New York, NY, USA, 2004. [Google Scholar]

- McBee, C. Towards a more affirming perspective: Contemporary psychodynamic practice with trans and gender nonconforming individuals; The University of Chicago School of Social Service Administration (Org); AdvocatesV Forum; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Stein, E. The mismeasure of desire: The science, theory, and ethics of sexual orientation; Oxford University Press: Demand, 2001; ISBN 9780195142440. [Google Scholar]

- Maier, S.F.; Peterson, C.; Schwartz, B. From helplessness to hope: The seminal career of Martin Seligman. In The science of optimism and hope: Research essays in honor of Martin EP Seligman; 2000; pp. 11–37. [Google Scholar]

- Costa, P.T.; McCrae, R.R. NEO PI-R Professional Manual; Psychological Assessment Resources. Inc: Odessa, FL, USA, 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.; Semmel, A.; Von Baeyer, C.; Abramson, L.Y.; Metalsky, G.I.; Seligman, M.E. The attributional style questionnaire. Cognitive therapy and research. 1982, 6, 287–299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poropat, A. The relationship between attributional style, gender and the Five-Factor Model of personality. Personality and individual differences. 2002, 33, 1185–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McLeod, S. Biological theories of gender. Simply Psychology 2014. Available online: https://www.simplypsychology.org/gender-biology.html.

- Nieder, T.O.; Richter-Appelt, H. Tertium non datur– either/or reactions to transsexualism amongst health care professionals: The situation past and present, and its relevance to the future. Psychology & Sexuality. 2011, 2, 224–243. [Google Scholar]

- Khodarahimi, S.; Rezaye, A.M. The effects of psychopathology and personality on substance abuse in twelve-step treatment programme abstainers, opiate substance abusers and a control sample. Heroin Addict Relat Clin Probl. 2012, 14, 35–48. [Google Scholar]

- Carver, C.S. How should multifaceted personality constructs be tested? Issues illustrated by self- monitoring, attributional style, and hardiness. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1989, 56, 577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Smith, C.P. Motivation and personality: Handbook of thematic content analysis; Cambridge University Press; ISBN 0-521-40052-X.

- Hodson, G.; Earle, M. Conservatism predicts lapses from vegetarian/vegan diets to meat consumption (through lower social justice concerns and social support). Appetite. 2018, 120, 75–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fallon, M.A.; Careaga, J.S.; Sbarra, D.A.; OʼConnor, M.F. Utility of a Virtual Trier Social Stress Test: Initial Findings and Benchmarking Comparisons. Psychosom Med. 2016, 78, 835–840. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- VanVoorhis, C.W.; Morgan, B.L. Understanding power and rules of thumb for determining sample sizes. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 2007, 3, 43–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Given, L.M. The Sage encyclopedia of qualitative research methods; Sage Publications, 2008; ISBN 978-1-4129-4163-1. [Google Scholar]

- Tongco, M.D.C. Purposive sampling as a tool for informant selection. Ethnobotany Research and applications. 2007, 5, 147–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bleiberg, E.; Jackson, L.; Ross, J.L. Gender identity disorder and object loss. J Am Acad Child Psychiatry. 1986, 25, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Di Ceglie, D. Gender identity disorder in young people. Advances in Psychiatric Treatment. 2000, 6, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stoller, R.J. The hermaphroditic identity of hermaphrodites. The Journal of nervous and mental disease. 1964, 139, 453–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McCrae, R.R.; Costa, P.T. Validation of the Five- Factor Model of Personality Across Instruments and Observers. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1987, 52, 81–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mahasneh, D.A.M.; Al-Zoubi, D.Z.H.; Batayeneh, D.O.T. The Relationship between Attribution Styles and Personality Traits, Gender and Academic Specialization among the Hashemite University Students. International Journal of Business and Social Science. 2013, 4, 286–295. [Google Scholar]

- Peterson, C.; Seligman, M.E.; Vaillant, G.E. Pessimistic explanatory style is a risk factor for physical illness: A thirty-five-year longitudinal study. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988, 55, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wegner, D.M.; Vallacher, R.R. Implicit psychology: An introduction to social cognition; Oxford University Press, 1977; ISBN-13: 978-0195022292. [Google Scholar]

- Budaev, S.V. Sex differences in the Big Five personality factors: Testing an evolutionary hypothesis. Personality and individual differences. 1999, 26, 801–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khodarahimi, S. Perfectionism and five-big model of personality in an Iranian sample. International Journal of Psychology and Counselling. 2010, 2, 72–79. [Google Scholar]

- Weisberg, Y.J.; DeYoung, C.G.; Hirsh, J.B. Gender differences in personality across the ten aspects of the Big Five. Front Psychol. 2011, 2, 178. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Löckenhoff, C.E.; Terracciano, A.; Bienvenu, O.J.; Patriciu, N.S.; Nestadt, G.; McCrae, R.R.; Eaton, W.W.; Costa, P.T., Jr. Ethnicity, education, and the temporal stability of personality traits in the East Baltimore Epidemiologic Catchment Area study. J Res Pers. 2008, 42, 577–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khodarahimi, S. Psychopathy Deviate Tendency and Personality Characteristics in an Iranian Adolescents and Youth Sample: Gender Differences and Predictors. European Journal of Mental Health. 2012, 7, 90–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

|

|

© 2018 by the author. 2018 Siamak Khodarahimi, Hassan Ali Veiskarami, Maria Mercedes Ovejero Bruna

Share and Cite

Khodarahimi, S.; Veiskarami, H.A.; Ovejero Bruna, M.M. Personality Dimensions and Attributional Styles in Individuals With and Without Gender Dysphoria. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2018, 5, 284-293. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P284293

Khodarahimi S, Veiskarami HA, Ovejero Bruna MM. Personality Dimensions and Attributional Styles in Individuals With and Without Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2018; 5(2):284-293. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P284293

Chicago/Turabian StyleKhodarahimi, Siamak, Hassan Ali Veiskarami, and Maria Mercedes Ovejero Bruna. 2018. "Personality Dimensions and Attributional Styles in Individuals With and Without Gender Dysphoria" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 5, no. 2: 284-293. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P284293

APA StyleKhodarahimi, S., Veiskarami, H. A., & Ovejero Bruna, M. M. (2018). Personality Dimensions and Attributional Styles in Individuals With and Without Gender Dysphoria. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 5(2), 284-293. https://doi.org/10.22543/7674.52.P284293