Cutis Verticis Gyrata in a Patient with Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas; Case Presentation and Review of the Literature

Abstract

:Introduction

Case presentation

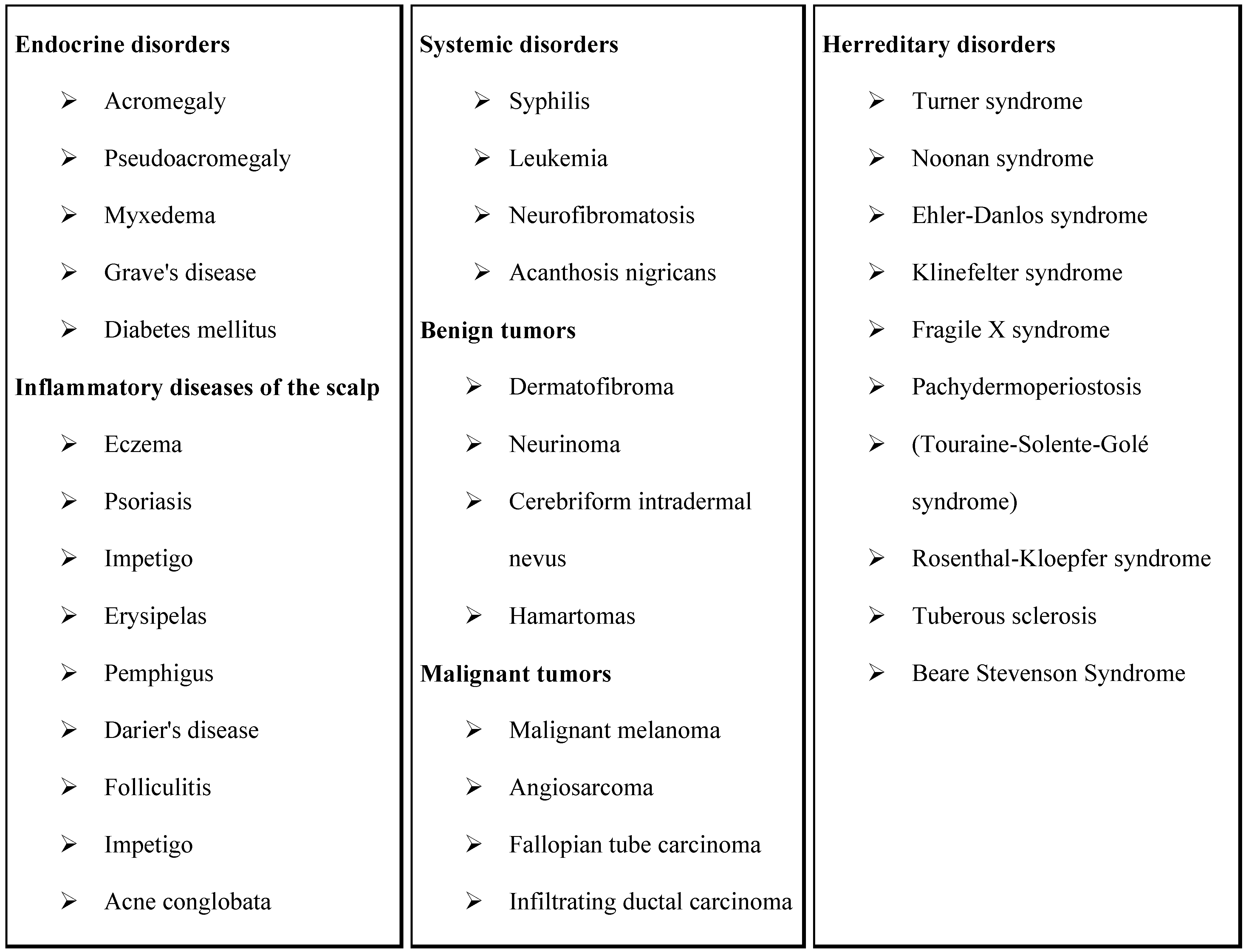

Discussions

Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- Taha, H.M.; Orlando, A. Butterfly-shape scalp excision: a single stage surgical technique for cutis verticis gyrata. J Plast Reconstr Aesthet Surg. 2014, 67, 1747–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larsen, F.; Birchall, N. Cutis verticis gyrata: three cases with different aetiologies that demonstrate the classification system. The Australasian Journal of Dermatology 2007, 48, 91–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- George, A.; George, L.; Mahabal, G.; Bindra, M.; Pulimood, S. Systemic T cell lymphoma presenting as cutis verticis gyrata. Indian Journal of Dermatology, Venereology And Leprology 2015, 81, 631–633. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Zhang, M.; Sun, Z.; Liu, Y.; Wu, S.; Lu, K. Rare giant secondary cutis verticis gyrata. Journal of Plastic Surgery And Hand Surgery 2011, 45, 212–214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hsu, Y.; Chang, Y.; Su, L.; Hsu, Y. Using novel subcision technique for the treatment of primary essential cutis verticis gyrata. International Journal of Dermatology 2009, 48, 307–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, H.; Teo, R.; Tan, A. Cutis verticis gyrata in a patient with hyper-IgE syndrome. Acta Dermato-Venereologica 2009, 89, 413–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.H.; Sano, D.T.; Martins, S.R.; Tebcherani, A.J.; Sanchez, A.P.G. Primary essential cutis verticis gyrata- Case report. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia 2014, 89, 326–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Åkesson, H.O. Cutis verticis gyrata and mental deficiency in Sweden. Acta Medica Scandinavica 1964, 175, 115–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Samira, B.; Meriem, D.; Oumkeltoum, E.; Driss, E.; Yassine, B.; Saloua, E. Cutis verticis gyrata primitif essentiel, une affection cutanée rare: cas clinique et revue de la littérature. The Pan African Medical Journal 2014, 19, 345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chia-Hsiang, C. Cutis verticis gyrata associated with chronic schizophrenia in Chinese. Biological Psychiatry 1989, 25, 636–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garden, J.M.; Robinson, J.K. Essential primary cutis verticis gyrata. Treatment with the scalp reduction procedure. Arch Dermatol. 1984, 120, 1480–3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Polan, S.; Butterworth, T. Cutis verticis gyrata; a review with report of seven new cases. American Journal of Mental Deficiency 1953, 57, 613. [Google Scholar]

- Yoo, K.H.; Lee, J.W.; Jang, W.S.; Li, K.; Seo, S.J.; Hong, C.K. Cutis Verticis Gyrata and Alopecia Areata: A Synchronous Coincidence? Yonsei Medical Journal 2010, 51, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aslan, C.; Tan, O.; Hosnuter, M.; Isik, D. Primary cutis verticis gyrata. J Craniofac Surg. 2015, 26, 974–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandoval, A.R.; Robles, B.J.; Llanos, J.C.; Porres, S.; Dardón, J.D.; Harrison, R.M. Cutis verticis gyrata as a clinical manifestation of Touraine-Solente- Gole’ syndrome (pachydermoperiostosis). BMJ Case Reports pii: bcr2013010047. 2013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Reilly, F.M.; Sliney, I.; O’Loughlin, S. Acromegaly and cutis verticis gyrata. Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine 1997, 90, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, T.M.S.; Sreekumar, N.C.; Sarita, S.; Thushara, K.R. Touraine Solente Gole syndrome: The elephant skin disease. Indian Journal of Plastic Surgery 2013, 46, 577–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tony Burns, Stephen Breathnach, Neil Cox, Christopher Griffiths. "Rook's textbook of dermatology", Eighth Edition ed; Wiley Blackwell, 2010; ISBN 978-1-4051-6169-5.

- Ferreira, F.R.; Ogawa, M.M.; Nascimento, L.F.C.; Tomimori, J. Epidemiological profile of nonmelanoma skin cancer in renal transplant recipients: experience of a referral center. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia. 2014, 89, 745–750. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marzuka, A.G.; Book, S.E. Basal Cell Carcinoma: Pathogenesis, Epidemiology, Clinical Features, Diagnosis, Histopathology, and Management. The Yale Journal of Biology and Medicine 2015, 88, 167–179. [Google Scholar]

- Goldsmith, L.A.; Katz, S.I.; Gilchrest, B.A.; Paller, A.S.; Leffell, D.J.; Wolff, K. Fitzpatrick’s Dermatology in General Medicine, 8th Ed. edMcGrawHill, 2012; ISBN ISBN 978-0071669047. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, D.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Guo, X.; Lang, Y.; Peng, L.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y. Treating cutis verticis gyrata using skin expansion method. Cell Biochem Biophys. 2012, 62, 373–376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berking, C.; Hauschild, A.; Kölbl, O.; Mast, G.; Gutzmer, R. Basal cell carcinoma—treatments for the commonest skin cancer. Deutsches Ärzteblatt International 2014, 111, 389. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lewin, J.M.; Carucci, J.A. Advances in the management of basal cell carcinoma. F1000Prime Reports. 2015, 7, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2016 by the authors. 2016 Simona-Roxana Georgescu, Maria Isabela Sârbu, Cristina-Iulia Mitran, Mădălina-Irina Mitran, Alice Rusu, Vasile Benea, Mircea Tampa. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Georgescu, S.-R.; Sârbu, M.I.; Mitran, C.-I.; Mitran, M.-I.; Rusu, A.; Benea, V.; Tampa, M. Cutis Verticis Gyrata in a Patient with Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas; Case Presentation and Review of the Literature. J. Mind Med. Sci. 2016, 3, 80-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1040

Georgescu S-R, Sârbu MI, Mitran C-I, Mitran M-I, Rusu A, Benea V, Tampa M. Cutis Verticis Gyrata in a Patient with Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas; Case Presentation and Review of the Literature. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences. 2016; 3(1):80-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1040

Chicago/Turabian StyleGeorgescu, Simona-Roxana, Maria Isabela Sârbu, Cristina-Iulia Mitran, Mădălina-Irina Mitran, Alice Rusu, Vasile Benea, and Mircea Tampa. 2016. "Cutis Verticis Gyrata in a Patient with Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas; Case Presentation and Review of the Literature" Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences 3, no. 1: 80-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1040

APA StyleGeorgescu, S.-R., Sârbu, M. I., Mitran, C.-I., Mitran, M.-I., Rusu, A., Benea, V., & Tampa, M. (2016). Cutis Verticis Gyrata in a Patient with Multiple Basal Cell Carcinomas; Case Presentation and Review of the Literature. Journal of Mind and Medical Sciences, 3(1), 80-87. https://doi.org/10.22543/2392-7674.1040